In Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris we read that the evolution of culture fosters print as the harbinger of revolution, the ultimate vehicle of free will. With the advent of the printing press, architecture, the stately orator of the ancient world, would give way to great stacks of printed pages—paper monuments that would be humanity’s legacy. Hugo’s novel was set in 1482, at the dawn of mechanized printing, and in it he embellished a world whose hierarchies and material logic collapse and scatter in the face of this new technology. Hugo writes, “In its printed form, thought is more imperishable than ever; it is volatile, irresistible, indestructible. It is mingled with the air. In the days of architecture it made a mountain of itself, and took powerful possession of a century and a place. Now it converts itself into a flock of birds, scatters itself to the four winds, and occupies all points of air and space at once.”1 Writing in stone bears little resemblance to writing on paper, adds Roland Barthes in connection to Hugo’s text, but it is the two forms’ comparability as vehicles for history, evidence of a shared past differently told, that makes Hugo’s monument-centric book so compelling.2

The events of the past remain unchanged, fixed in the resin of history, but as they are recalled time after time, articulated in place after place, the past reappears abridged, distorted, and adulterated. Remembering is bipartite—there is the committing of information to long-term memory, and its subsequent recall.3 How and what we remember is directly related to the technology used in constructing that remembrance, and Hugo saw a revolutionary potential in the shift from stone to paper for cultural inscription. The story told by monuments is “necessarily incomplete and mutilated,” but told through books, printed and reprinted ad infinitum, it passes “from duration to immortality.”4 This description of externalized memory seems particularly germane to the Internet age, where incomplete and mutilated facts take on a beauty all their own.

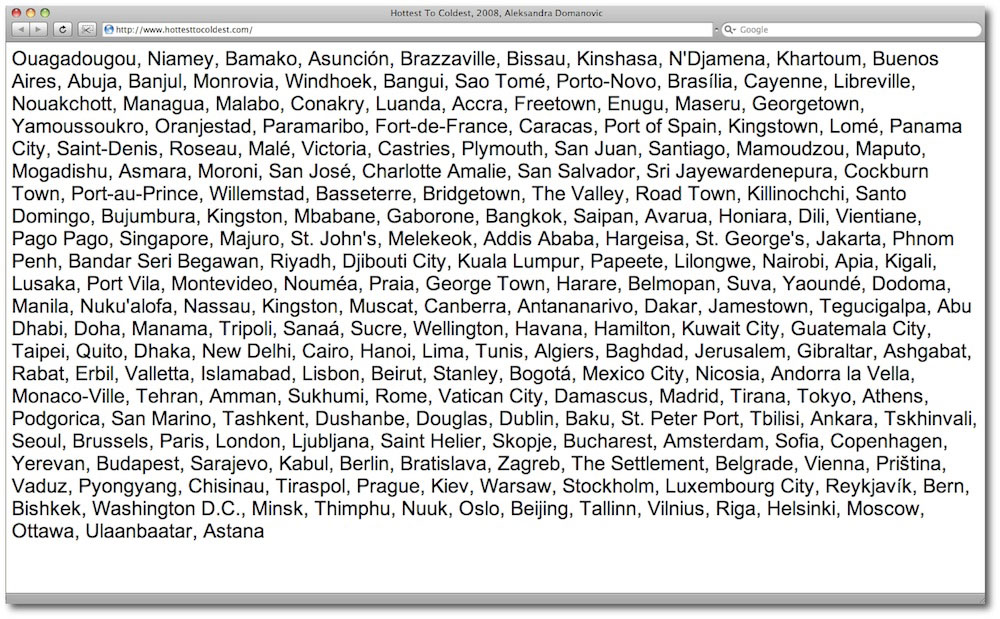

Much of Aleksandra Domanović’s work gestures toward this contemporary condition. Hottest to Coldest (2008) is a website that lists the world’s capital cities in descending order by temperature. Itemized in large black letters on a white background, the site is updated every few minutes and presents the world’s capitals with digital, deadpan delivery. Gone is any semblance of geopolitical consciousness (rarely does one see Pyongyang listed with such nonchalance next to Oslo, Budapest, and Helsinki), as if to annul the culture, politics, and decisions each nation considered in naming a capital.

We glimpse affinity—island cities like Manila and San Juan look at ease together, while Bern and Baku jive in alliteration—only to realize the extent to which we project identity onto swaths of sunny or chilly land with which we are otherwise scantly acquainted. In recent years, much has been made of the online flattening of hierarchies, geographies, and other inequalities—anyone can edit Wikipedia, broadcast on Twitter, and organize on Facebook. Less has been said about how websites, search engines, scroll bars, Wi-Fi, and their underlying codes have mediated and transformed our taste and perception. As Hugo noted, our common history is altered by our memories of it, which in turn are altered by the means with which they are recorded. Even as a list, Hottest to Coldest is unreliable—it actually changes with the winds. Not unlike nature itself, Domanović’s site is governed by a predetermined, self-consistent logic that’s blind to human inclinations.

Like Hottest to Coldest, Domanović’s large-scale outdoor sculpture Monument to Revolution (2012) embraces sweeping yet disparate geopolitical themes, rearranging them in a wholly contextual yet deeply foreign way. Commissioned by the 4th Marrakech Biennale (of which I was a co-curator), Domanović created a 6-meter-tall version of one of the three colossal raised fists of the anti-Fascist monument of Bubanj Memorial Park in Niš, Serbia.

Completed in 1963 by Croatian sculptor Ivan Sabolić, these concrete obelisks are part of a memorial complex that include a kilometer-long memorial trail and a 23-meter-long marble relief that depicts the mass extermination of Serbs, Roma, and Jews by German execution squads between 1942 and 1944. Hundreds of monuments like the fists were erected throughout the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to commemorate World War II battles. Commissioned under the presidency of Josip Broz Tito, massive concrete forms would bloom in the very locations where battles were fought and patriots fell. Monstrous angel wings unfurl on the mountain plateau of Tjentište; overgrown starfish stretch their arms over the hills of Kosmaj. Before the fall of socialism and the breakup of Yugoslavia, people would be bused by the thousands around the country to visit these monuments. Beyond commemorating terrible events, these monuments, or spomeniks, served to solidify a new national identity, one that rose at the hand of men and women at the very place where they were once attacked. Today, almost all lie in ruined disrepair.

To rebuild one of Sabolić’s fists in Marrakech is to attest to the mutability of what was once dogmatic and steadfast—the facade of a sovereign anti-Stalinist Yugoslavian identity under Tito’s command.5 What does it mean to replicate a national monument from a country that no longer exists? If the ideological impetus for identity building through spomenik is gone, the need to remember the atrocities of war is not. Yet since the dissolution of Yugoslavia, few gather at the park to commemorate Niš’s liberation each October 14. Sabolić had intended the fists as a backdrop to an outdoor theater large enough for 10,000 spectators. Today, the park is most visited by revelers on May 1, International Labor Day.6 Spomeniks, particularly those in rural settings, were all but forgotten until Antwerp-based photographer Jan Kempenaers published images of them in 2010.

Soon after, these began circulating on the Internet, where art and architecture enthusiasts, as well as amateur political scientists from around the globe, were captivated by their otherworldly appearance.7 For Serbian architect Srdjan Jovanović Weiss, the spomeniks vanished from lived experience the moment the ideology that produced them ceased to exist. Their reappearance as curios constitutes a reconciliatory “act towards the future.”8 Resolution, Weiss implied, didn’t take place with the nationwide building of spomeniks. World War II was a complex time for Yugoslavia, as much about brutal infighting along ethnic lines as about liberating itself from Nazi Germany. Where the Partisans, Ustaše, and the Chetniks fought and killed one another, a postwar Yugoslavian monument needed to recognize both the victim and the perpetrator.9 But like icing over a poisoned cake, these hulking, abstract, narratively neutral concrete objects did little to alleviate and absorb postwar tensions. Casting a new light on the spomeniks as Kempenaers did with his photographs, or Domanović with her facsimiles, allows us a detached yet sustained glance at something difficult to look at in reality.10

Central to the spomeniks’ meaning is their location at the site of wartime killings, an already heavy chain of contextual signification. Domanović’s rendition of Sabolić’s defiantly clenched fist in Marrakech thus complicates its historical position. Who or what is intended to be commemorated? What is the relationship between a Yugoslavian war monument and the city of Marrakech? In developing Monument to Revolution, Domanović—born in Novi Sad in 1981 and raised in Slovenia—learned that both Yugoslavia and Morocco were members of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Cold War response of solidarity from countries not formally associated with either the Western or Eastern bloc. One of the movement’s spearheads, Tito, was eager to promote a global future that would preserve his country’s hard-won independence—a course welcomed by other newly autonomous nation-states including India, Indonesia, Egypt, and Ghana, as well as Morocco, which joined in 1961, just as the Berlin Wall was being built.11

Further challenging any easy reading of the work, Domanović sited her outsized sculpture in the Cyber Park Arsat Moulay Abdessalam, an 80,000-square-meter oasis in the center of Marrakech’s bustling medina—a few minutes’ walk from the mercantile clatter of Djmaa al Fna square.12 The park’s central axis runs roughly east to west; a secondary axis runs perpendicular. The gates of the exorbitant Royal Mansour Hotel are at the southern end, and Monument to Revolution is at the northern entrance, while the park’s water feature is at the axial crossing. Sited at the crossroads of Morocco’s cultural and economic symbolic pressure points, Domanović’s spomenik underscores a no less ideologically driven purpose in Morocco than it might have in Yugoslavia.

Rosalind Krauss has marked the beginning of postmodern sculpture with a moment in the late 1960s when sculpture became defined by what it wasn’t—neither landscape nor architecture.13 Where sculptures, like monuments, used to “sit in a particular place and speak in a symbolic tongue about the meaning and use of that place,” now they were most simply determined in the pure negative as “what is in the room that is not really the room.”14 Krauss diagrammed a Klein four-group, a device used by Structural theorists to expand meaning based on relational oppositions. The diagram is drawn as a square, with landscape and architecture at the top, non-landscape and non-architecture at the bottom. Between non-landscape and non-architecture, Krauss located sculpture. Postmodern sculpture, it seems, still indexed its meaning to traditional cultural determinants like architecture and landscape. Krauss also noted that sculptures and monuments are historically bounded objects, not universal ones, yet to this condition, Domanović offers an addendum through the cultural logic of the Internet.15 Unlike the relative categorical order of 1979, the year of Krauss’s observations, public manifestations like monuments are more readily defined by the social media created by the constant efflux of instant digital communiqué than they are by official mandate.16 A quarter of the world’s population is currently connected to the Internet, each person continuously redefining the parameters of their language, what words and images mean, and who uses them. Monument to Revolution is a smaller version of an obelisk built to commemorate wartime killing in southern Serbia and sits in a park owned by Maroc Telecom. Perhaps it makes most sense as a Google search of itself—every available answer to any question about it (“What is a Yugoslavian war monument doing in Marrakech?”) being as valid, truthful, and satisfactory as the next.

Unlike the solid concrete obelisks in Niš, Domanović’s spomenik is made of wood and finished with a sun-bright fuchsia tadelakt—an ancient Moroccan high-polish surfacing technique made by rubbing lime plaster with smoothed stones. The unnatural color of pink plastic flamingos, the fist, singular and defiant, sits on ocher gravel pavement, among swaying palms and trimmed hedges. North African social turmoil dominated international news in spring 2012, right as Domanović was conceiving of and installing her work. As visitors to Marrakech encountered the giant pink fist, they might infer that the "revolution" in the work’s title was the so-called Arab Spring—the raised, clenched fist a universal symbol of resistance. Permeating the park is free wireless Internet, which acts as an invisible attractor as much as the garden’s lush serenity. Huddled in groups, sitting alone, or standing at one of the park’s public Internet booths are people peering intently into screens. The uprising of citizens in the Arab world against oppressive governments was quite definitively a revolution: Governments were challenged, some were dismantled, and the power of broadcast was brought to grassroots political use. In the park, as people milled about, directed as if by some unseen force emanating from their screens, “revolution” seemed more aptly characterized by the gradual domination of the Internet over physical, offline reality.

At play here is the status of surface. As mentioned, Monument to Revolution is covered in Moroccan lime plaster, tadelakt, as if dressing a twentieth-century Yugoslavian monument in Moroccan garb would justify its incongruous, conspicuous presence in the Maghreb. But perhaps the thin layer of tadelakt does suffice to signify its claim to Moroccan patrimony. Ubiquitous today in most Moroccan interiors, especially those geared toward tourists, tadelakt is an old technique used to waterproof hammam (Turkish bath) interiors that was popularized in the 1970s and ’80s by architect Charles Boccara. Tunisian-born but raised in Casablanca, Boccara was trained at the École des Beaux-arts in Paris; when he graduated in 1968, he moved to Marrakech to start his practice. Boccara, along with designers Stuart Church and William “Bill” Willis, is often credited with popularizing neotraditional Moroccan architecture—a style that combined Moroccan forms, ornaments, and materials with the demands of Western comforts and lifestyle.17 Boccara is also often cited as the architect who brought tadelakt out of the cisterns and hammams and “back” into vogue with contemporary Moroccans. Boccara uncoupled the material from its original function as a sealant and made it into a signifier of premodern Moroccan life—the material’s inconsistencies of color and variations in texture convey a pastiche of a preindustrial, prestandardized, mythical North African past.18 In Marrakech, new hotels, or riads, are routinely covered in tadelakt to supply guests with the touch and feel of authentic Moroccan culture, cleanly bypassing the half-century of colonial rule.19

Contemporary viewers, like those at Cyber Park, are accustomed to receiving information from surfaces. Televisions, ATMs, computers, and smartphones are magic mirrors that conjure texts and images on their surfaces at a moment’s whim. One is reminded of Fredric Jameson’s characterization of postmodernity’s depthlessness.20 The surface of an iPhone is where we focus our attention, and the depth of our investment seems commensurate with its thickness. Krauss suggested that between landscape and non-landscape we will find the marked site (Smithson, Heizer), but what becomes of a site marked with screens? For the theorist Andrew Darley, the viewer of digital media is a sensualist, not an interpreter, “positioned first and foremost as a seeker after unbridled visual delight and corporeal excitement.”21 The surface, whether of touch-sensitive glass or tadelakt, is thus a vehicle for delivering images. The surface is mutable—it has no stake in history, yet it can appear historical. In this way, Monument to Revolution is not a monument in Krauss’s sense of a place-specific object that speaks symbolically of its purpose. It is a monument because it is an image of a monument.22

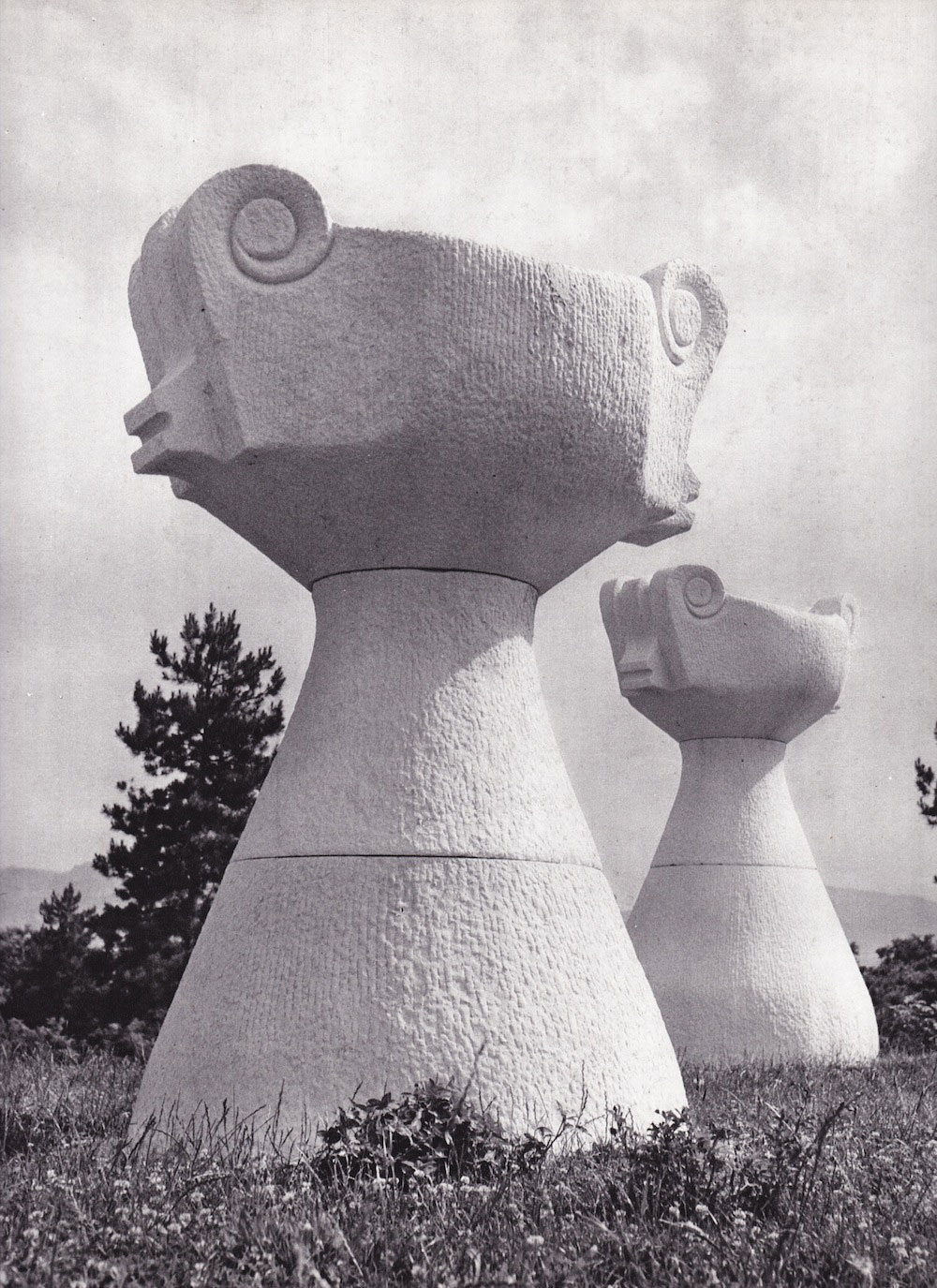

In “From yu to me,” Domanović’s solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel (April 1–May 28, 2012), which took up the entire ground floor, the artist showed another tadelakt spomenik. In 1961, Serbian architect Bogdan Bogdanović designed a group of seven cenotaphs for Prilep, a city in central Macedonia. Standing at full scale, about 3 meters tall, Prilep Nymph (2012) is a foam replica of one of Bogdanović’s monuments. Shaped like a squat Ionic column and covered in smoky cyan tadelakt—a hue between Facebook and Skype blue—the work seems desperate yet unable to gesture at anything beyond itself.2324

In the art museum, history and tradition have simply become a surface condition, a look. Made to last only for the duration of their respective exhibitions, Monument to Revolution and Prilep Nymph were made to be destroyed, existing today, imperishably, as descriptive images online and in print. Where in Marrakech, the illusion of material solidity was maintained for the Monument to Revolution (it is, in fact, a hollow, wood-framed object), in Basel, surface is revealed as a mere outer coating. Lining the inside frame of the doorways between the different galleries with yellow tadelakt, Monochrome doorframe (Kunsthalle Basel) (2012) reads as a deliberately impassive mapping of one place onto another. Marrakech, known for its city walls and the many filigreed gates penetrating it, is gestured at by a veneer of pigment on a few doorframes—the passing of an entire history breached by a threshold.

The idea that objects have taken on characteristics usually deemed image-like is most explicit in Domanović’s stacked-paper works. Since 2009, Domanović has been producing what she calls “printable monuments.” Sheets of A3 or A4 paper are stacked into piles of varying heights. By using full-bleed ink-jet desktop printers, an image appears on the lateral sides of each stack. Domanović sees these stacks as stelae commemorating the defunct .yu Web-address suffix—Yugoslavia’s Internet domain suffix, used by Montenegro and Serbia until 2010, long after Yugoslavia’s dissolution in the early 1990s. In one group of prints, Domanović presents iconographic images from the new Balkan countries; in another, we see images from 19:30 (2010–11), a video that juxtaposes footage from Yugoslavian newscasts with partygoers. In both stelae we see crowds—Serbian football hooligans, Balkan ravers—staring out in an image made from the layered edges of the stacked sheets. Like the leaves of paper that together make these solid blocks, a crowd is held tenuously by the power of common purpose—and both could scatter at any moment. On some stacks, the pictures are revealed in swiped strokes, as if the lateral surfaces of the piled paper were Photoshop files, each stroke erasing the surface to expose people beneath. The stelae exist also as PDFs, easily disseminated by email or USB drive and reconstituted anywhere with a desktop printer. Yugoslavia, its placelessness affirmed in virtual space when .yu was deleted, now finds unrestricted physical manifestation in the form of piled paper. The Internet lacks physical shape or substance, and paper lacks depth, but in Domanović’s stacks, the two produce an alloy capable of reflecting the histories of such a distant yet recent past.

untitled [30.III.2010,] 2010, installation view, “From yu to me”, Kunsthalle Basel. Photograph by Gunnar Meier.

Here, the printed page did indeed surpass architecture and place, but not in the way Hugo had imagined. Built forms can be forgotten, but they are not obsolete. And if it was the idea of increasingly immaterial media replacing what came before that drove Hugo to make those pronouncements, his ghost would likely be aghast at the myriad adaptations and reworkings his novel has received—his own book has itself become “volatile, irresistible, indestructible.” Notre-Dame de Paris has been translated into almost every language (in English about once every ten years since 1831); inspired at least eleven musicals (including an 1836 opera and a 1998 rock version); been subject of ten statues of note, including the Rossetti’s marble Esmeralda and Her Goat, Djali (1865); muse to innumerable paintings, drawings, and lithographs; the basis of four ballets, two radio plays, and a song, released in 2009, by Austin-based band Some Say Leland, about Quasimodo throwing himself a birthday party; the topic of five television series, one of which features Quasimodo, Esmeralda, and François as superhero friends who fight villains and obstruct evil plots; ten films (Disney’s animated musical version of 1996 itself became a comic book, a live-action show at Disney-MGM Studios, a restaurant, a direct-to-video sequel, and a video game); and even a 1939 graphic novel by the Serbian Ivan Šenšin, Zvonar Bogorodičine crkve. Most of Notre-Dame de Paris’s incarnations bear little resemblance to Hugo’s original—the main characters remain archetypes, the narrative is sometimes merely suggested. Contrary to Hugo’s warning, what hasn’t changed, what hasn’t been mutilated by the passing of time and technology, is the image of Notre-Dame, the cathedral monument that looms at the heart of the story. What this means is hard to say.

-

Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, trans. and ed. John Sturrock (London: Penguin, 2004), 196. ↩

-

Roland Barthes, "Semiology and the Urban," in Rethinking Architecture, ed. Neil Leach (London: Routledge, 1997), 159. ↩

-

See Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 18. ↩

-

Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, 196. ↩

-

See Misha Glenny, The Rebirth of History: Eastern Europe in the Age of Democracy (London: Penguin, 1993). ↩

-

See Armin Linke and Srdjan Jovanocić Weiss, Socialist Architecture: The Vanishing Act, ed. Tobias Bezzola (Zurich: JRP|Ringier, 2012), 110. ↩

-

A blog post from early 2011 titled “25 Abandoned Yugoslavian War Monuments That Look Like They’re from the Future” has garnered more than 400 comments about Tito’s rule and the evolution of Yugoslavia’s identity, while clearing up basic questions about Yugoslavia’s postwar affiliation (many erroneously believe it was a Soviet state). See http://cracktwo.com/2011/04/25-abandoned-soviet-monuments-that-look.html. ↩

-

Linke and Weiss, Socialist Architecture, 101. ↩

-

Willem Jan Neutelings, “Spomenik: The Monuments of Former Yugoslavia,” in Spomenik, Jan Kempenaers (Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2010). ↩

-

In Domanović’s Turbo Sculpture (2010–13), a twenty-minute video essay, the artist discusses the proliferation of public monuments depicting international celebrities and film characters in former Yugoslavian countries. A statue of Johnny Depp stands in Drvengrad, Rocky Balboa in Žitište (both in Serbia), and a polished bronze statue of Bruce Lee was unveiled in Mostar, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 2005. The video suggests that the difficulty of memorializing the reality of the recent past led communities to find celebrities and fictional characters to publicly and metaphorically express their sentiments. Mostar’s population is divided along ethnic and religious lines. Bruce Lee, both Chinese and American, was chosen by the Mostar Urban Movement youth group to symbolize unity in an ethnically divided city. ↩

-

Today, the movement has 120 member states, but an alliance of those who wish to remain unattached seems burdened by conflicts in its own internal logic. For example, one of the movement’s principal tenets, of mutual noninterference between members, guarantees that no one is held accountable for positions declared at each summit. See Robert Shaplen, “The Paradox of Nonalignment,” The New Yorker, May 23, 1983. ↩

-

Established in the eighteenth century by the Alaouite prince Moulay Abdessalam, the park, or arsat, was enlarged in 1920 under the French protectorate, before being completely renovated in 2005 by Maroc Telecom, which funds the administration of the park and has outfitted the grounds with free wireless Internet. The park sits north of and adjacent to the Royal Mansour Hotel, King Mohammed VI’s sumptuous hotel, which also began construction in 2005. The king was prompted to build the most luxurious hotel in Africa in order to attract more tourists. ↩

-

Rosalind E. Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979): 33. ↩

-

Ibid., 36 ↩

-

Ibid., 33 ↩

-

See Andrew Keen, Digital Vertigo: How Today’s Online Social Revolution Is Dividing, Diminishing, and Disorienting Us (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2012). ↩

-

Brian Brace Taylor, “Charles Boccara of Morocco,” MIMAR: Architecture in Development 15 (1985): 41–61. ↩

-

For a more nuanced account of the mythifying and aestheticization of Moroccan identity, see Katarzyna Pieprzak, Art and Modernity in Postcolonial Morocco: Imagined Museums (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). ↩

-

Bypassing historical periods disagreeable to the status quo is a strategy Domanović had reflected on when developing Monument to Revolution. The tendency in many Yugoslav republics is to make new public art and architecture projects look premodern, avoiding modernist forms that could recall the ideologically complicated post–World War II era. See Carson Chan and Nadim Samman, eds., Higher Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale 4 in Context (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012), 318. ↩

-

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism; or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 1991), 8–10. ↩

-

Andrew Darley, Visual Digital Culture: Surface Play and Spectacle in New Media Genres (London: Routledge, 2000), 169. ↩

-

For another iconic image-as-monument see “I am a monument” in Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1972). ↩

-

As if to underscore the unlikely artistic connection between former Yugoslavian states and Morocco, the curator Adam Szymczyk organized a collaborative exhibition by Latifa Echakhch (Moroccan) and David Maljković (Croatian) on the museum’s upper level, which opened the same night as Domanović’s show. Echakhch and Maljković’s exhibition, “Morgenlied” (or “Morning Song”), expands on the ethos of Enlightenment from which the Kunsthalle, both as an institution and as a building, was forged in the late 1860s. Like Domanović, Echakhch contends with the perception of history by manipulating surface. The artist dripped black India ink over each of the ninety-six panes of glass from the 80-square-meter skylight in the museum’s Oberlichtsaal. Light streams usually into this grandly proportioned hall, illuminating its trappings, as if phenomenally cultivating the tenets of Enlightenment, the habits of the bourgeois, and the virtues of fine art. The ink darkens the panes, which in turn dim the museum room. ↩

-

Maljković’s offerings were spare, abstained—an unloaded projector aimed at the wall displayed an empty rectangle of light. His usual commentaries on the vanishing weight of former Yugoslavia’s monuments were themselves absent here, which injected a sense of loss to the memory of a contested past. Yet that which is forfeited to the thinning of history can often be recouped in the market. Case in point: A few months after Domanović, Echakhch, and Maljković opened their respective exhibitions on April 1, 2012, Cuban artists Los Carpinteros exhibited a replica of Bogdanović’s 1971 Kosmaj spomenik at Sean Kelly Gallery’s Art Basel Miami booth. Standing 2½ meters tall, and surfaced with red LEGO® blocks, Kosmaj Toy (2012) quickly set off a host of online reviews, announcements, and blog posts. None made mention of the fallen Yugoslav Partisan soldiers of which the original commemorates; rather, many noted its $110,000 price tag, and that it sold within ten minutes of the fair’s opening. ↩

Carson Chan is an architecture writer and curator, pursuing a PhD in Architecture at Princeton University. He has curated many exhibitions of contemporary art and architecture, including the 4th Marrakech Biennial with Nadim Samman and the Biennial of the Americas 2013. His writing appears in books and periodicals worldwide, including Kaleidoscope, where he is a contributing editor, and 032c (Berlin), where he is editor-at-large.