I’m bidding on a presidential library…an Olympics with an annuity that gives every year.

—Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel1

When the Obama Foundation issued its request for qualifications for a presidential library in March 2014, it drew a remarkable amount of national attention to the wide-ranging public pressures that inform the making of such civic monuments. Cities across the country bid against one another, each laying claim to Barack Obama’s personal history (including Honolulu, his birthplace, and Columbia University in New York, his undergraduate alma mater) as well as showcasing themselves as welcoming hosts for scholars and the public alike. Emanuel’s pithy remark that Chicago’s stake in the competition for the library was practically Olympic in scale and benefit is a reminder that gaming and one-upmanship are now par for the course when attempting to secure major architectural programs.

To make complicated matters even more so, the Chicago mayor and a public-private taskforce were just as assiduously working in parallel to lure the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art away from competing bids in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The Chinese architects MAD were commissioned to produce what could be taken for an alabaster space mountain, given George Lucas’s sci-fi oeuvre. The design, now maligned in the popular press (“Jabba the Hutt’s Palace” became a popular and politically charged zinger), certainly transforms the designated site—an “eyesore” of a parking lot servicing the Soldier Field football stadium—but this intervention has often been viewed as an affront to the city’s mostly continuous 26-mile ribbon of lakefront park.2

Insinuated in some of the formal criticism were (arguably elitist) demerits from cultural arbiters in the media, pivoting swiftly from sniffs at a design that “sneers” at Chicago’s architectural heritage to swipe at the “awfully thin” collection that the building would be expected to contain, which ranged from Norman Rockwell illustrations to Jurassic Park memorabilia.3 Despite this chilly reception, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which the Hutt/Mountain, like Anish Kapoor’s “Bean,” is one day embraced as a complement to the many monuments and institutional gems set in the City Beautiful–era greensward on the Chicago lakefront. Alternatively, protecting the park from Lucas’s MAD-designed building would delay improvement of the asphalt tailgating lot into verdant parkland until some future moment in which financing for a public good like a park (without an external driver like a museum—or an Olympics) becomes available. As for the chances of encouraging Emanuel and Lucas to regroup their planners to find a more palatable site—perhaps one located more adjacently to the African-American community of Bronzeville—consider only that Lucas has already begun courting Los Angeles power brokers, should the legal efforts in Chicago to obstruct his lakefront plans succeed.4

Both the Lucas and Obama projects exemplify a current tendency that frames the future of cities through a desire for the “Bilbao effect,” in which high-profile cultural edifices yield long-term economic development. Increased tourism is vaunted as an obvious benefit of winning a cultural anchor, from which accrue more loosely defined gains in the form of “economic development and job creation.” Despite the popular appeal of the putatively “public benefits” that these projects’ financial returns present, both endeavors have faced opposition by historic preservationists, who have argued for a higher and more explicitly cultural standard by which to measure the public’s vested interest.

This high-minded opposition to the siting of the Obama and Lucas projects in public parks has rallied behind the slogan “Forever Open, Clear and Free”—a phrase that evokes an inviolable trust handed down by city forebears, who apocryphally “refused” to squander Chicago’s natural heritage by programming the lake for commercial gain. Arguably, the Lucas project has suffered more from the popular media’s unflattering coverage, which has focused on the patron’s immense wealth. The emphasis on one man’s fortune behind an ostensibly nonprofit foundation, together with doubts about the project’s didactic value, have tended to render the Lucas Museum as a private or commercial concern, and have thus undermined the project’s claim to public benefits that would justify offering the Lucas Museum public land at far below its “market value.”

The Obama Library, in contrast, is asked to represent the reconciliation of centuries of thwarted African-American claims to centrality in the national historical conscience. Such a weighty symbolic claim on public space presents quite a different challenge to the preservationists’ appeal to a nineteenth-century conception of conservation. Considering the African-American community’s deeply held expectations that the Library deliver long-deferred political, cultural, and economic returns, the arguments about preserving the park are roughly tantamount to exclusion of a long-denied monument from Chicago’s most representative cultural landscape—the “front yard” lakefront parks, whose icons signify civic virtue, power, and shared values.5 The preservationists’ challenge to the Obama Library seems to have been sidelined by an alliance forged between powerful political brokers and black community stakeholders. To circumvent a potential preservationist lawsuit that could deliver the Obama Library to a strong contending proposal in West Harlem from Columbia University, this alliance hatched cover-of-night legislation that ultimately benefited the Lucas Museum as well.6

While Mayor Emanuel has framed Chicago’s investment in the library as one playing out on the global city field (with the possibility of Chicago’s loss to presumed rival New York the most chilling prospect for the second city’s ambitions), the reality has been that Chicago’s “bid” encompasses disparate historically disinvested communities on the city’s South and West Sides. These neighborhoods, competing for the metaphorical Olympics, share higher-than-average rates of poverty, unemployment, crime, struggling commercial districts, and lower life expectancy than other communities in Chicago.7

Even with the Obama Foundation declaring the University of Chicago’s bid the winner in April 2015, the two neighborhoods adjacent to the campus (Woodlawn to the south and Washington Park to the west) continue to vie for the ultimate final siting. Considering the scale of these neighborhoods’ needs, one might well wonder how this single “victorious” site could be capable of delivering “Olympian” benefits in response to widespread public expectations. It challenges us to ask what happens to the losers of these games of public benefit: Are the preservationists right in challenging the Obama Library to fulfill its progressive mandate by maintaining the aesthetic integrity of the parks as public right? Should Chicago’s aspirations for economic development be furthered by placing the library on a more urban site? Overall, how might all cultural projects best serve the public good?

the University of Chicago.

Cultural Landscape and “Public Ground”

Historically, all along Chicago’s lakefront, real estate power brokers have defined the boundaries of parks. They cultivated civic relationships that benefited their commercial interests—the price the public would pay for the realization of “public grounds.” Today it’s difficult not to notice the legacy of these compromises in the presence of railroads running alongside (and through) Chicago’s most prominent parks. Significantly, this legacy of commingled private and public interests (and benefits) created both of the major parks adjacent to Hyde Park and the University of Chicago (Jackson Park bounding it to the south near Woodlawn and Washington Park to the west) that remain in play as the university determines the final site and architect for its winning Obama Library bid.

The authors of “Forever Open, Clear and Free”—the mantra of Chicago’s park preservationists—are three canal commissioners who served on that body at a time when the solvency of the federal Treasury was supported by the sale of land “purchased” cheaply from the Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa peoples in treaties resolving what had been a constant state of warfare. The most lucrative sites of this speculation included shipping canals connecting Lake Michigan, the Chicago River, and the Mississippi River, opening up a continuous water route between the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast via the Erie Canal. This system linked new sites for commerce and generated a booming real estate economy, a twinning of infrastructure and speculation with seemingly unlimited upsides and which, with New York’s global capital behind it, boosted Chicago’s wealth and prominence above regional rivals.8

These commissioners were charged with the sale of “unsettled areas” to pay for this critical new shipping canal. The last parcel to be capitalized was Fort Dearborn, the historic “military reservation” that had protected trade and supported military operations for U.S. territorial expansion. As this prominent piece of lake- and river-fronting federal property was subsumed in private real estate parcels, the commissioners identified a zone for public use—the shorthand on the drawing was “public ground,” a term that has since resonated through Chicago’s understanding of its own landscape resources. At a time when more established metropolises were increasingly building parks as emblems of cosmopolitan status, Chicago’s audacious vision of itself as a potential mid-continental capital was limited by constraints on its public revenues, and its public ground was but sparsely ornamented.9 The integrity of this lake-facing public space, roughly the site of today’s Grant Park and Millennium Park (then named “Lake Park”), was compromised most notably in 1851. Unable to get federal appropriations to protect lake view homesteads from shoreline erosion and flooding, the city council authorized ceding a right-of-way through the lake that the Illinois Central Railroad reclaimed as a breakwater and railroad trestle.

The seemingly incongruous overlay of Illinois Central tracks and lakefront parks remains a salient feature of Chicago’s landscape into the present—visible as the tracks emerge between the new Renzo Piano and old Beaux Arts wings of the Art Institute and continuing south along the lakefront. The tracks run through Hyde Park, home of the University of Chicago, where in the 1850s Paul Cornell (a New York lawyer and Chicago real estate investor) had deeded property to the burgeoning Illinois Railroad to serve his envisioned bedroom community. Cornell was among the Chicago business elite who lobbied the legislature to establish Park Commissions modeled on the one that completed New York’s Central Park between 1858 and 1871. In 1869, three distinct commissions were created with jurisdiction over each major geographic zone radiating around the central city (South, West, and Lincoln in the north). The South Park Commission, eyeing the grand vision of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in Manhattan, contracted Olmsted & Vaux to articulate plans for a connected set of parks, one along the lake called Jackson, a ribbon park running east-west that became known as the Midway, and an inland park with a north-south orientation called Washington Park. Once completed, the improvements would surely be a boon to property owners who dominated zones of the city as Cornell did in Hyde Park. But without a mechanism to finance the plans for realizing the parks as cultural landscapes, the sites within the boundaries established for these public improvements lay fallow. In fact, it would take the commercially inclined White City World’s Fair of 1893 to generate the capital revenues to complete the landscapes around which the Obama Library’s demands now coalesce.

Competition and Preservation

For many years, “open, clear and free” public grounds were not taken literally and the boundary of the commons was understood to be open to a great many kinds of public use. Because there were strict statutory limitations placed upon the potential to expand the boundary of the public grounds when other public needs arose, the city turned to these designated public spaces and established programs for buildings “in the parks.” In fact, Dearborn Park, the first public ground to be developed as such, was entirely consumed by the construction of the Chicago Public Library in 1892 (currently the site of the Cultural Center, which happens also to be the site of 2015’s inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial, another Emanuel initiative). Along with the construction of the Art Institute in 1891, this broader interpretation of the planning statute was made possible by virtue of “consents” signed by all adjacent private property owners that gave them legal ground for action should disputes arise.

Montgomery Ward’s dry goods business at 10 South Michigan overlooked the railroads and sparsely finished “public ground” along Lake Michigan. He took equal issue with the liberal interpretation of the statute and with the city’s lax approach to improvement and maintenance of its public grounds. He first filed suit in 1890, demanding Chicago clear the lake of what he termed “unsightly structures.” Ensuing lawsuits put him at odds with his commercial peers, including Marshall Field (another department store executive), who sought to finance the pedagogical natural history museum and monument illustrated at the center of Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago. Marshall Field’s collection had initially been on display as part of the White City fair in Jackson Park, but that temporary structure (today’s Museum of Science and Industry) was deemed unsuitable for the long-term care of the objects (which ironically includes archaeological and anthropological items of the native cultures whose displacement by the forces at Fort Dearborn produce that clear space for the new park).

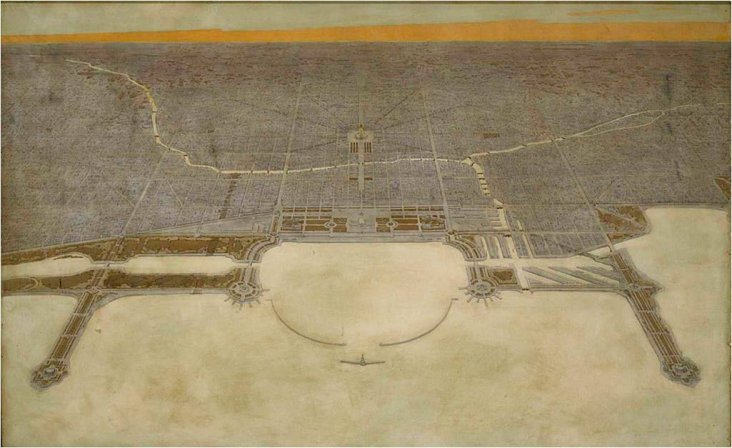

the Proposed Harbor, and the Lagoons of the Proposed Park on the South Shore,” Plan of Chicago, plate CXXVII. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Behind the formal legacy of Chicago’s parks, which recall London’s Birkenhead and New York’s Central Park in their monumental greenswards, are the social practices of the commissioning class, whose new etiquette-bound traditions of parlor calls, visits, and promenades demanded formalization in a natural context. Against these “cultivated, cosmopolitan and gregarious” expectations of how the new parks would be programmed, how dire a contrast Chicago’s underdeveloped Lake Park must have appeared then to Montgomery Ward as he gazed from his consumer emporium across an expanse replete with “stables, squatters’ shacks, mountains of ashes and garbage, the ruins of a monstrous old exposition hall, railroad sheds, a firehouse, the litter of one of the circuses that continually moved in and out, discarded freight cars and wagons and an armory rented out for prize fights, wrestling matches and… masquerade balls.”10

A broad and perhaps motley public certainly enjoyed (and drew revenue from) this variegated environment of informal housing and escapist entertainments, vaguely reminiscent of the Coney Island boardwalks that were being viewed around this same time by New York’s park visionaries as the very antithesis of the intention of their designs.11 Taking a rigid stance that park programming excluded any other public function or benefit, Ward opposed a number of proposals supported by the City of Chicago for what they argued were “public uses” congruent with the intent of the “public ground,” including armories and parade grounds, a civic center, a post office, and a police station.

In a final 1909 decision, Ward’s staunch interpretation of the “forever open, clear and free” clause was pitted against a broad set of city stakeholders hoping to realize Burnham’s vision of a Field Museum at the center of Grant Park. In that case, the court validated museums as a proper program for parks, with a clear public benefit. This suited the elite consensus of the day and validated the symbolic alignment of monumental buildings set in the landscape elsewhere in the city.

But Ward got his way, too. Setting the legal precedent by which contemporary landscape preservationists have positioned their opposition to the Obama Library, the court refused the South Park Commissioners’ ability to “deny Ward’s right to an open view of Grant Park.”12 Ward, as a private property owner, held the public to the promise of the map that claimed “an unobstructed view of Lake Michigan” as the incentive for all those speculators with the wherewithal to buy up the plats carved out of Fort Dearborn. Ward’s victory validated the rights of the private property owner at 10 Michigan Avenue. Here, the covenant between private owner and public promise is most symbolized not by the European-styled Buckingham Fountain that was substituted for a museum at the park’s center, but by the towers that have begun to clamor to extract more rents from behind the historically protected Michigan Avenue street wall.

It might seem that winning games for public benefit paved the way for Chicago’s arrival on the national and global stage over a century ago, when it knocked St. Louis out of contention for the 1893 World’s Fair. But it wasn’t simply the loss of a World’s Fair that saw St. Louis (and then Chicago) grapple for attention through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Over time, shifting forces in the economy and related investments in infrastructure—from canals to railroads, armaments to manufacturers, highways to fiber optics—come to determine geographic winners and losers. Small farms yield to plantations, cities to suburbs, Rust Belts to Sunbelts, and the like. These enormous (and geographically moving) investments, tied to global networks, are the “cake” that city leaders fight for. World Fairs, biennials, Olympics, starchitected museums are perhaps just the icing on that cake. Even with these forces aligned in its favor at a critical moment in its history, “winning” civic nodes like Chicago depended on compromise with railroads and commercial fairs to subsidize completion of its public cultural landscapes and infrastructures.

Considering the complex histories and exigencies for Chicago’s museums on parkland, we can ask: How might the official library of the first African-American president engage the monumental contradictions of its historical programs, of museum and park? Might an alternative to the building commission be defined such that Chicago’s (and Harlem’s and Honolulu’s) non-winning neighborhoods (the “losers” in this competition) could expect to share in hitherto geographically defined public benefits from cultural amenities, and perhaps go even further to tap into the structural reservoirs of economic and political power that ultimately determine questions like what gets built, where, how, and for whom?

Toward a Public Commission

As the library comes into existence, bids for the commission and the oversight of the design of its capital-A architecture will be undertaken by a complex entity—a client, let’s call them a “commissioner”—forged from multiple stakeholders. The Obama Foundation has released a request for proposals to selected architecture firms, kicking off what will likely be a lengthy design process among many arbiters. The foundation can also be expected to lead fundraising and to steward the president and first lady’s vision for the future and their legacy, just as the Lucas Museum will be steered by a foundation of its own. The City of Chicago will hold the deed to the park property. The National Archives and Records Administration will operate the library, and traditionally sets standards on design, construction, and endowment specifications guided by its integration into a broader system of federal presidential libraries. The University of Chicago’s role as host might be expected to enhance the “capacity” of the nascent organization’s efforts to raise funds, and its ability to extend the impact of its vision through the existing programmatic and intellectual infrastructure of a large and venerable university. It’s up to these expected stakeholders with seats at the commissioning table to invite others to share that power.

As that power is apportioned, they would do well to consider how a more inclusively conceived commissioning body might more adequately represent the racial and class experiences of one man and his family in the pedagogical components of the library’s architecture. How does the library, as a place but also part of an institutional federal system, address (if not transform) the “community” understood as a network of black economic and cultural efforts that have been rigorously excluded from public space nationally and isolated through publicly supported mechanisms of segregation from private residential communities? At the intersection of a still rather new typology and a collection of potential sites that convey a set of black narratives that have been generally excluded from the historical record, the library commission might broaden not only who sits at the table but what’s included within the boundaries of the proper public uses and benefits yielded by its programming. This uniquely American building type has evolved from FDR’s ersatz and homey Dutch Colonial museum and library in upstate New York into an amalgam of temple, monument, tourist attraction, and think tank. Fulfilling a pedagogical program, these libraries connect the public to the legacy and mythology of the democratic office conceived as the apotheosis of the American dream. As a part of Chicago’s tourist infrastructure, the library serves as a kind of museum, delivering a public narrative of the Obama presidency through play (an approximated Oval Office), dialogue, and experience set against his biography, political accomplishment, and measures of his legacy. The historical singularity of Obama’s presidency undoubtedly raises the stakes for what this kind of architecture might be expected to deliver.

Where the conventional diagram of cultural sites (the City Beautiful park and monument) produce, and then disguise economic benefits, African-American grassroots cultural projects are inherently and visibly rooted in the day-to-day vulnerability of commercial and domestic sites (from the International African Museum birthed in Dr. Charles Wright’s Detroit office basement to Margaret Burrough’s Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art conceived in a Bronzeville carriage house).

Though the Ebony Museum of Negro Art gained “Museum in the Park” status in 1971 when the Chicago Park District donated a park service building as the home of what is now called the DuSable Museum, its independence remains at risk even today.13 Many other community cultural institutions of this period have vanished. Most notably, the Wall of Respect, a mural developed collectively by twenty-odd contributors and comprising an outdoor “museum” of black history on the South Side, was lost to a fire that accelerated plans for urban renewal. Similarly Art and Soul emerged as a gang-created community center of intergenerational art-making and education in a West Side neighborhood heavily scarred in the unrest following the Martin Luther King assassination. It was unfortunately vulnerable due to its dependence on unsustainable revenues from foundation grants, “Johnson money” and a partnership with the downtown Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art.14

The transience and demise of these cultural institutions parallels the fragility of commercial districts, the gradual decimation of their surrounding residential fabric, and the relative powerlessness of community organizing and community development entities to substantially or sustainably reverse trends rooted in larger socioeconomic forces.15 As Obama reflects in his early memoir on his work in the Far South Side Chicago Housing Authority complex known as Altgeld Gardens, it isn’t concerns with the quality or maintenance of housing that most concerns his colleagues and constituents. It is the paucity of jobs and the structurally voided access to capital. Those years in Chicago coincided with the administration of Harold Washington, Chicago’s first black mayor, inaugurating “equity planning” and high levels of community engagement in city building.

Pushing back against the tradition of commercial financing of public goods like the parks, Washington’s most dramatic success at wresting power from vested interests was in stopping the Chicago World’s Fair bid of 1983, which had been presented as the “most feasible way to assemble funding” for continued improvements of the city center (a common argument that arises in Olympic-bid horse-trading). Washington’s attempts to refuse the long-standing political, social, and planning practice of bidding competitively to commission private interests to subsidize public benefits remind us of practices that date back to platting and seizing of properties at the city’s inception. Alternatively, he endeavored to create an “exaction tax” that would redirect the supply-side logic of the city’s real estate development engine. His plans were derided as a form of “extraction” (with opponents pointing to connotations of extortion) and blocked in the racially divided City Council.16

The ways that parks create lucrative benefits to private entities are hardly surprising or even particularly clandestine, as the skylines made up of luxury towers that have begun to sprout along Chicago’s Grant and Millennium Parks attest. The public doesn’t need architectural critics to connect the dots between the symbolism of museums in the park, and the creation of private benefits on the edges of that park. Community demands put to the Obama Foundation, along with the proliferation of progressive entities we all hope might be incubated through its largesse, look to benefit from this system, extracting value for contingent communities suffering from barriers to black ownership and the segregation of African-American markets from the broader market.

Ultimately, a presidential library is, for all its potential and imagined connections to economic power, a public institution. Might it not stand apart from this system of games, competition, and supply-side economic benefit? A radically inclusive process of community engagement would invite this excluded public to share the commissioning power assumed by the library, the federal government, and major civic stakeholders. This inclusive commissioning would inherently shift concern from competing entities proximate to the winning location (be those in the cultural, commercial, or housing markets) to the systemic and widespread good that might come from thinking differently about this type as building and landscape, pedagogy and symbol, financing and subsidy, philanthropic mission and public work.

Such a “winning” library would endeavor to change the game, reorganizing the programmatic “playing field” to yield benefit not only in Woodlawn or Washington Park, but also Lawndale and Bronzeville, West Harlem and Kaka’ako Makai. The library would recognize how the disparities between Hyde Park and Washington Park may have played out in sister programs, including the Johnson Library removed from historically black East Austin by highway infrastructure, or in the recasting of high-rise public housing adjacent to Kennedy’s library on Columbia Point in Boston as a model “mixed-income community.” It might rewrite the covenants by which our presidential monuments remember power and leadership, recast history and learning, and ask enduring public entities to serve the living public and the future.

-

Katherine Skiba, “Mayor Emanuel sees prize in Obama library, not bid for Olympics,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 2015, link. ↩

-

This most entertaining reference and similar variants recurred in local architectural reviews but resonated most pointedly in the world of politics, in the words of Alderman Bob Fioretti, “It looks like a palace for Jabba the Hutt. I was wondering what planet we are on.” The alderman and mayoral challenger assailed the Lucas design’s cultural, political, and economic connections, which tapped into a narrative about an “out of touch” mayor more attuned to “planet Hollywood” and other distant centers of power and wealth than the mundane struggles of Chicago neighborhoods, during a hotly contested election campaign that ultimately pushed Emanuel into a runoff, the first for a sitting Chicago mayor in decades. Fran Spielman, “Futuristic concept for Lucas museum touches off civic debate,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 4, 2014, link. For the architectural reframing of Fioretti’s Jabba the Hutt jab, see Blair Kamin, “George Lucas’ museum proposal is needlessly massive,” Chicago Tribune, November 6, 2014, link. ↩

-

Justin Davidson, “George Lucas Museum of Narrative Art Looks Ridiculous,” New York, November 6, 2014 link. ↩

-

Patrick Kevin Day, “George Lucas says Museum could land in LA if Chicago falls through,” Los Angeles Times, January 16, 2015, link. ↩

-

Mabel Wilson documents the architectural, institutional, and curatorial activism by which “black Americans…claim a physical space in the nation’s symbolic cultural landscape and a symbolic space in the nation’s historical consciousness, two spheres in which their presence and contributions have been calculatingly rendered invisible and abject for over two centuries.” See Mabel O. Wilson, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 3. ↩

-

Greg Hinz, “Clout at Work: Obama library, Lucas museum bill zips through Legislature,” Crain’s Chicago, April 23, 2015, link. ↩

-

Whet Moser, “Why Washington Park Makes the Most Sense for the Obama Presidential Library,” Chicago Magazine, May 2015, link. ↩

-

During the administration of President Jackson, federal easing of credit “fueled a manic search for new places in which to invest,” creating a speculative and competitive frenzy in the 1830s. See William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1991), 32–33. ↩

-

“In city after city the most enthusiastic proponents of parks were also the most aggressive boosters of the city itself—of its commerce, industry, and ascendency in competition with other cities… As landscape architecture vied for a place as one of the fine, or refined, arts, parks came to be widely viewed as essential elements of metropolitan attainment, as one of the ‘chief ornaments of the city.’” Daniel Bluestone, “From Promenade to Park: The Gregarious Origins of Brooklyn’s Park Movement,” American Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 4 (Winter 1987): 530. ↩

-

The passage quoted in this sentence is from Lois Wille’s Forever Open, Clear and Free: The Struggle for Chicago’s Lakefront (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 73. Daniel Bluestone finds social ideals and practices of “well-dressed residents, with parasols and walking sticks in hand, on foot and in carriages, departed home and congregation for the broader world of the promenade” reflected in the planning practices of the era. Bluestone, “From Promenade to Park.” ↩

-

Brooklyn park commission president James S.T. Stranahan dismissed Coney Island for its “incongruous and offensive associations such as the huckster, the caterer to low amusements, gambling paraphernalia and other unsightly and obtrusive enterprises.” Bluestone, “From Promenade to Park.” ↩

-

Lawrence Okrent, “How Daniel Burnham Accomplished Less (and More) Than He Intended To,” The Plan of Chicago at 100: 15 Views of Burnham’s Legacy for a New Century (Chicago: Ely Chapter, Lambda Alpha International, 2009). ↩

-

Mary Mitchell, “DuSable Museum Fight Exposes Generation Gap,” Chicago Sun-Times, July 18, 2015, link. ↩

-

For the histories of The Wall of Respect and Art and Soul (an outgrowth of the Conservative Vice Lords gang) see Jeff Huebner, “The Man Behind the Wall,” Chicago Reader, August 28, 1997, and Rebecca Zorach’s interview with Ann Zelle in Never the Same: Conversations About Art Transforming Community in Chicago and Beyond, link. ↩

-

CDCs in Chicago have been “often shaky operations, struggling for the capacity to influence trajectories in their communities. Economic ventures proved difficult to sustain, and many turned to housing…which could readily attract subsidies through existing federal programs…meant less attention to other neighborhood needs such as health care, job training and job creation.” D. Bradford Hunt and Jon B. DeVries, Planning Chicago (Chicago: American Planning Association, 2013), 101. ↩

-

For more on how Reagan-era cuts conspired with racial city politics to derail the progressive Harold Washington agenda, see Hunt and DeVries, Planning Chicago, 73–76. ↩

Todd Palmer is the Associate Director and Curator of the National Public Housing Museum. He practices as a curator, artist, planner, educator, and exhibition designer, and holds a Masters of Architecture from columbia university GSAPP.