Back when Carl Sandburg’s “big-shouldered city” had risen out of the pages of Poetry magazine just seven years before, when Jane Addams still lived in Hull House, when Pine Street’s transformation into Michigan Avenue (as recommended in Burnham and Bennett’s Plan) was still fresh, and when recent émigré Alphonse “Al” Capone could be found working as a bouncer at the Four Deuces nightclub on the Near South Side—his arc lamplit shadow not yet scaled to obscure the city’s interwar history—a twenty-eight-year-old writer named Ben Hecht began publishing a column in the Chicago Daily News that staked its own claim in the development of the city’s modern urban imaginary. Titled “Around the Town: A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago,” the feature debuted on June 23, 1921, and would appear daily (excepting Sundays, the Daily News’ day of rest) for more than fifteen months. Slotted into the two leftmost columns on the paper’s back page, its content constituted Hecht’s attempt to prove, sketch by sketch, his “Big Idea,”

that just under the edge of the news as commonly understood, the news often flatly and unimaginatively told, lay life; that in this urban life there dwelt the stuff of literature, not hidden in remote places, either, but walking the downtown streets, peering from the windows of sky scrapers, sunning itself in parks and boulevards. He was going to be its interpreter. His was to be the lens throwing city life into new colors, his the microscope revealing its contortions in life and death.1

So wrote Henry Justin Smith, Hecht’s Daily News editor, in his preface to an anthology of the column published in November of 1922. Smith’s apparent enthusiasm for Hecht and his writing likely explains in part why “A Thousand and One Afternoons” (which became 1,001 Afternoons in book form) attained its unusual placement within the newspaper. For though Hecht’s wide-ranging, fictionalized pieces about the city and people who inhabited it declared their literary ambitions through language, form, tone, and various conceits (not to mention were explicitly framed as “literature” by Smith and Hecht), they were not printed among the paper’s literary features in its feuilleton section that then followed sports and preceded the letters to the editor. Instead the “Afternoons” shared their back-page territory with five fat strips of daily comics and an ad space that grew or shrank each day in response to Hecht’s fluctuating verbosity. This was prime Daily News real estate: a key commercial site, easy to access (just unfold the issue and flip over—no page turning required), where many paper buyers might go first for their daily entertainment, and where many advertisers would pay dearly to try to capitalize on those eyeballs.

This sort of value, of course, is latent in most periodicals’ back page—or equivalent—but in 1921 Chicago the space possessed particularly heightened stakes. With popular radio still in its infancy, newspapers remained the dominant news medium across the United States. In Chicago, the financial and political gains to be made through newspaper publishing had by the early ’20s given rise to a highly competitive, sometimes literally cutthroat, environment. Circulation wars were underway between the city’s major English-language papers, with rival paper owners hiring thugs to threaten, roughen up, and even murder competing distributors and readers. At the same time, rising professional calls for “objectivity” hadn’t yet altered the practices of most Chicago journalists and publishers. Newspapers retained explicit political alliances, and for writers, the main game remained to find a story and tell it as compellingly as possible, without qualms about bias or yellow journalism restricting their work.2

It was within this volatile discursive field and highly public space that Hecht would construct and circulate, day by day, his imagined Chicago. Smith may have touted the project’s artistic value in his preface, but he and his cohort must have recognized its commercial prospects as well. They did have ample local evidence that giving writers room to experiment with overtly literary approaches, in addition to regularly encouraging vivid reportage, could produce content that would move papers. From the late nineteenth century onward, Chicago newspapers had employed a notable number of aspiring novelists, playwrights, poets (including the aforementioned Sandburg), and other literary hopefuls, some of whom had parlayed their reporting and other work into regular columns where they could take greater artistic liberties.3 Hecht himself had begun his career at the Daily News at the age of seventeen, in the now-obscure job of picture stealer, and had worked his way up the reporting ranks while simultaneously writing novels and plays.4

Within this rich, if relatively young, journalistic-literary tradition, Hecht’s “Afternoons’” most direct precursor may have been “Stories of the Streets and Town,” a column by the writer George Ade that ran in the Chicago Record throughout the 1890s. Ade’s feature incorporated a number of recurring characters inspired by people he had met through his reporting work, many of whom (like Ade himself, from small-town Indiana) had come from the Midwestern hinterlands. Capturing the anxieties and difficulties of their rural-to-urban transitions, and treating them in a humorous way, Ade’s column had quickly gained an avid readership. It was collected in multiple anthologies and inspired an independent novel, published in 1896.5 Today one of the “Stories” most apparent characteristics is Ade’s use of the city’s evolving vernacular, the idiosyncrasies and complexities of which speak directly to Chicago’s extraordinary growth during this period. Between 1880 and 1890 the city’s population doubled from five hundred thousand to more than a million (79 percent of that population had been born abroad or were children of immigrants), then doubled again to 2.2 million by 1910.6 This was the same year Hecht arrived in Chicago.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants who’d relocated to Racine, Wisconsin, at the turn of the century to open a women’s clothing business, he’d decided to come to the city to work rather than matriculate at the state university.7 As his job at the Daily News pushed and pulled him through gridded streets, alleys, and all the spaces in between, it also introduced him into a fray of writers, artists, musicians, directors, actors, filmmakers, editors, publishers, architects, and others who had been drawn to Chicago by the growing number of arts-related employment opportunities, institutions, and venues, many of them funded by the city’s rising patron class and stimulated by the project of the 1893 World’s Fair. The literary strain of this cultural ecosystem would eventually become known as the Chicago Renaissance. Its key participants included writers such as Sandburg, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, and Edgar Lee Masters, all aiming to make art of the everyday experiences of modern Midwestern cities and their imbricated hinterlands. Equally crucial were critics, editors, and publishers like Poetry’s Harriet Monroe and the Little Review’s Margaret Anderson, who brought these writers’ distinct realist projects into circulation and conversation with other unfolding literary attempts to explore, describe, and decipher modern life then underway in Europe and the eastern United States.8

When Hecht took to his typewriter in 1921 to knock out the first of his “Thousand and One Afternoons,” he was writing as a colleague, apprentice, rival, and friend of these other Chicagoans-in-Renaissance, engaged in negotiating and capturing in his own way a city where commerce, culture, industry, agriculture, art, and architecture collided and fed each other, sometimes in ways that had never been seen before. If we can believe Smith, his urban vision was a smashing back-page success: “His letter-box became too small for his mail. He was bombarded with eulogies, complaints, arguments, ‘tips,’ and solicitations.” But in the ensuing near-century since, Hecht’s urban vision has largely faded from popular consciousness. To revisit it today— whether through navigating the fits and starts of Daily News library microfilm or cracking open a first or facsimile anthology—is to encounter a complex and contradictory cosmopolis on the American prairie, a Jazz Age Chicago whose defiance of neat categorization challenges us to expand our notions of the city, past and present—and continues to entertain.

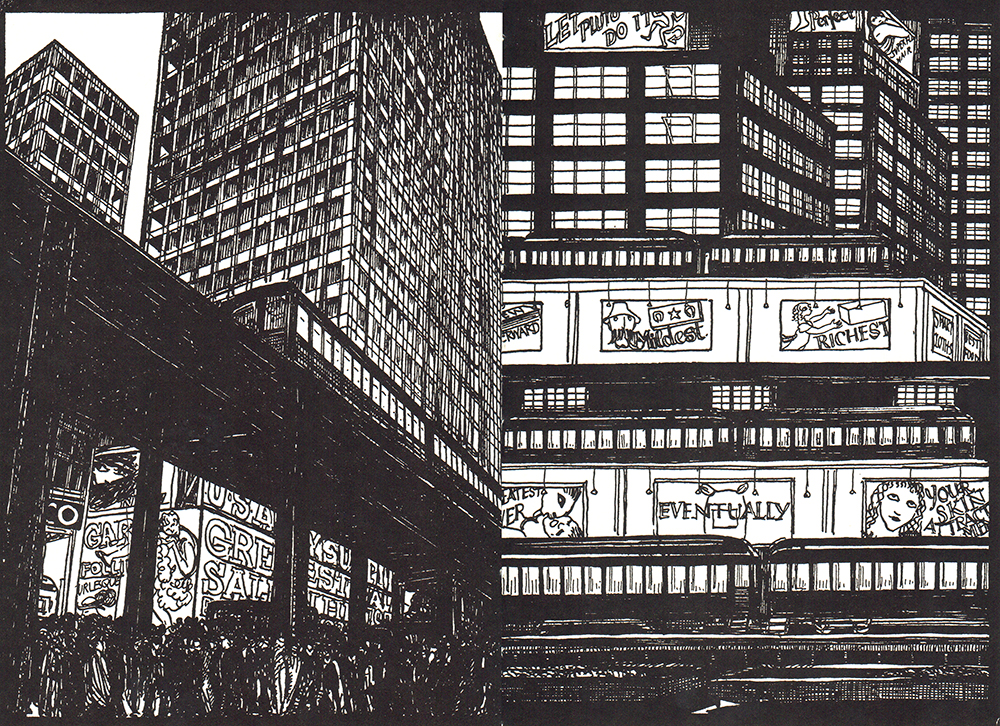

The “Afternoons’” original graphic treatment in the Daily News provides a fitting frame through which to reenter Hecht’s Chicago. Set off by a boxed heading announcing the column’s title in large, uppercase type (a kind of marquee), it also sported a different historiated initial each day that was customized to include an illustration of a character, object, or setting central to each sketch—most often, a person or building. Considered together, these small but eye-catching drawings illustrate the overall composition of Hecht’s stories, which can be roughly divided into pieces that focus on illuminating the lives of particular city-dwellers and pieces that focus on the city itself—its built and natural environments, often interwoven.

Even briefly examining a sampling of the Chicagoans featured in the “Afternoons” is enough to suggest the historical gulf between Ade’s Chicago of the 1890s and Hecht’s Chicago of 1921, and, moreover, to gloss the differences between their urban ambits. Whereas Ade’s “Stories” focus in or near the downtown Loop on characters whose backgrounds were relatively similar to his own, Hecht’s column comprises a huge, motley cast with just a few recurring players, conjuring a constantly shifting human kaleidoscope of class, race, ethnicity, gender, nationality, political affiliation, and employ, dispersed throughout the city and its neighborhoods. In “Don Quixote and his Last Windmill,” for example, the wealthy, mustachioed box factory owner Mr. Sklarz (a Russian Jew who fought in the Crimean War) relates the story of his life over a bowl of soup in the back of a dark saloon. On the near West Side, down the block from her apartment above “a candy, book, and notion store,” the grief-stricken central character of “Mrs. Sardotopolis’ Evening Off” asks a gypsy in a doorway to read her “work-coarsened palm” after losing the youngest of her children. Within the inner office of 2209 Wentworth Avenue in the city’s “very efficient, very conservative Chinatown,” Billy Lee slips his story’s titular necklace of “Coral, Amber, and Jade” over his “American coat and American silk shirt” and makes a deal with a recent aristocratic arrival from Wuchang. Joining characters like these, who may have been simulacra of certain people Hecht knew or more composite creations, were then-contemporary, nonfictional Chicago residents and prominent visitors. Clarence Darrow and theologian George Burman Foster debate in “Schopenhauer’s Son”; Sergei Prokofiev, Boris Anisfeld, Mary Garden, and Jacques Coini rehearse the first performance of Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges at Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium Theatre in “Fantastic Lollypops”; and George Ade himself is discussed in “The Man from Yesterday.”

Hecht’s heterogeneous universe sprawls further with his dissolution of conventional borders dividing urban from hinterland, native from immigrant, and city from nature. Throughout the “Afternoons,” young women from the small-town Midwest picked up on prostitution charges invoke and evoke their rural roots, never transitioning from country to city or “pure” to “impure,” but flickering somewhere in between. First-generation immigrants in many stories act as fixtures in their Chicago neighborhoods while simultaneously conducting business, personal, and imagined lives in their distant hometowns. And one column, “Animals in the Loop,” devoted to describing and reflecting on the daily lives of cats, dogs, horses, and birds in the city, treats these animals on equal footing with human Chicagoans, positing a decidedly modern yet non-anthropocentric urbanity.

Amplifying the shifting quality of Hecht’s Chicago is his use of different literary forms and techniques to structure and present his sketches. Mixing high and low language, genres, and references (sometimes surgically, other times sloppily), he seems to take advantage of the “Afternoons’” serial format to experiment with aestheticizing urban experience more liberally than most of his Chicago Renaissance cohort. As Smith would catalog them, his “comedies, dialogues, homilies, one-act tragedies, storiettes, sepia panels, word-etchings, satires, tone-poems, fugues, bourrées—something different every day” blend the commercial with the literary and borrow from other forms of art and media. Of particular note is his importation and incorporation of techniques from theater and cinema, which he was also working in at the time, and which would become his principal realm after he left Chicago in 1924 for New York and then Los Angeles to work as a Broadway playwright and Hollywood screenwriter.9

The primary thread binding together the “Afternoons” in all their heterogeneity is the figure of Hecht himself. In many of the pieces his fictional stand-in is present as a character, and he otherwise communicates his authorial and narrative presence in ways both explicit (his name filling the marquee byline) and implicit (from his signature turns of phrase to the rhythms of his sentences). It is tempting to label him a flâneur and to place his project firmly within that evolving literary practice rooted in nineteenth-century Paris. But if Hecht can be called a flâneur, the role requires some serious revisions. Far from a dispassionate dandy who strolls at his leisure, observing the bourgeois buzz of the arcades and grand boulevards, he is “the newspaperman” (his auto-epithet throughout the “Afternoons”) who crosses the city because it’s his job to seek out its stories. He knows its streets, courts, streetcars, grand homes and tenements, office buildings and factories, railyards and prison yards, and people of all types who live and work there, largely because he makes his pay by telling the city what the city is up to. And on his days off, or at night, after the paper has been put to bed, he comes to know its other parts by spending his pay on amusements high and low—at the cinemas, opera and playhouses, burlesques, brothels, and jazz clubs—or finding himself in a space between leisure and work—in a park, on a train, on a bridge—where he stares out at the city, waiting or loitering.

Completely at home in Chicago’s commercial-artistic environment, he seems wholly uninterested in maintaining a flâneur’s traditional position of remove. In fact he is constantly repositioning himself in relation to the city’s physical spread and his perceived identification with its populace, locating himself at varying degrees from the heart of each “Afternoon’s” plot or the direction of its narration. The urban chaos around him heightens rather than disturbs his experience; it is his element and his material, his inspiration and his daily bread. When he does despair, it’s not over an unattainable urban past and its associated socioeconomic order (now lost on a grand scale) but his own inability to adequately describe the particular, present Chicago in which he sits, stands, and stares, whether out over its rooftops or into the depths of its neon-charged river.

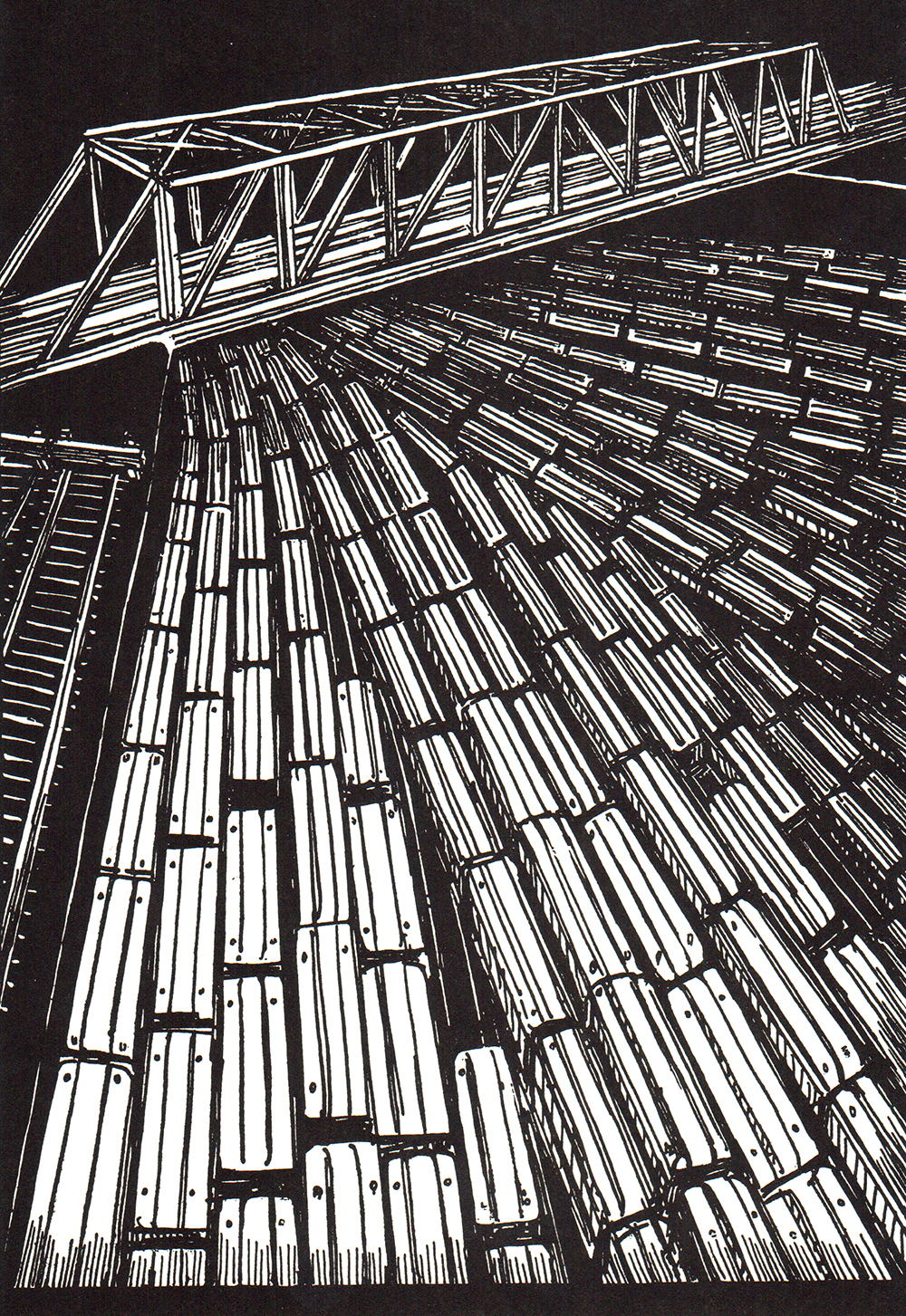

It is in these quieter moments of the “Afternoons”—the sketches in which Hecht’s narrator focuses his gaze on the physical city—that his project remains most compelling. The story “Night Diary,” included here in full as a facsimile of the anthology’s 1922 first edition, is one of the richest of these moments. Standing on the swing bridge that then spanned the Chicago River at State Street (two bridges west of the double-decker Michigan Avenue span Burnham and Bennett had so desired), Hecht’s newspaperman takes in the nighttime city along with the several other “loiterers” who “stare into the scene,” elbows set on the railing and faces “hidden in their hands.” Contemplating the boats, warehouses, and tall buildings that line the river, extending into endless shadows to the west, he arrives at a distinctly Chicago realist call to arms:

Do you know the dark windows of the city, you gentlemen who write continually of temples and art? Come, forget your love for things you never saw, cathedrals and parthenons that exist in the yesterdays you never knew. Come, look at the fire escapes that are stamped like letter Z’s against the mysterious rectangles; at the rhythmic flight of windows whose black and silver wings are tipped with the yellow winkings of the corset and ice cream signs. The windows over the dark river are like an alphabet, like the keyboard of a typewriter. They are like anything you want them to be. You have only to wish and the dark windows take new patterns.

Metaphor, simile, and other traditional literary devices, the newspaperman goes on to discover, are no longer enough to decipher and describe his world. Now it is the modern built environment itself that the writer must look to in order to interpret his experience. Its buildings have not only developed an abstracted language of their own, but also appropriated the newspaperman’s dearest technology—the typewriter—with which to record their messages.

Notably, however, as Hecht establishes in “Night Diary” and many of the “Afternoons’” other sketches, this is a built environment inextricably linked with its human creators and freely mixing with nature. Chicago’s skyscrapers, bridges, ships, automobiles, industrial machines, electric lights, and other engineering feats not only share space with the fog, lake, river, and moon, but work in constant, active combination: reflecting, refracting, and transposing one another into an urbanity so unprecedented that even the eclectically silver-tongued Hecht falls silent in his attempts to explicate it. To join him back in its streets, meeting its people and staring into its irresolvable shadows, is to see past “City Beautiful,” “City of Broad Shoulders,” “Garden City,” and “Gangsterland” backdrop, and into a far more provocative modern metropolis.

-

Henry Justin Smith, preface to Ben Hecht, 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009). First published in 1922 by Covici-McGee. ↩

-

This background is drawn largely from Bill Savage’s introduction to the University of Chicago’s 2009 reprint edition of 1,001 Afternoons (see note 1 for full citation). In reference to the violence of the 1920s circulation wars, Savage cites Michael Lesey, Murder City: The Bloody History of Chicago in the Twenties (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2007), 305. ↩

-

For more on the relationship between Chicago newspapers and literary talent, please see two entries in the Chicago History Museum and Newberry Library’s online Encyclopedia of Chicago: Bill Savage’s “Journalism,” link, and Timothy B. Spears’ “Literary Careers,” link. ↩

-

Bill Savage on “picture stealing” in his introduction to 1,001 Afternoons: “In the days before reliable and portable photographic equipment, newspapers had to illustrate their circulation-raising stories of urban mayhem with photographs that had already been taken. So when a murder, a suicide, or a sex scandal developed, editors had to obtain family portraits of the dead or disgraced, even though grieving or ashamed families for one craven reason or another might resist sharing such images with their fellow Chicagoans. This trade required its practitioners to be smooth as a con artist and bold as a second-story man, to talk the family out of that formal portrait taken in happier times, or to just steal the damn thing and flee on foot while the mourners were distracted by the minister praying over the deceased.” ↩

-

For more on Ade’s life and work, see his entry in the Biographical Dictionary of American Newspaper Columnists, ed. Sam G. Riley (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995), 4–5. ↩

-

Walter Nugent, “Demography: Chicago as a Modern World City,” in the online Encyclopedia of Chicago, link. ↩

-

William MacAdams, Ben Hecht: The Man Behind the Legend (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1990), 11. ↩

-

Carlo Rotella’s “Chicago Literary Renaissance” entry in the online Encyclopedia of Chicago, link, discusses these players and more, as well as how their work relates to similarly intense and significant periods of Chicago literary activity at the turn of the century and during the 1930s–40s. ↩

-

As Bill Savage notes in his introduction to 1,001 Afternoons, Hecht’s work in Hollywood was extraordinarily successful: “Perhaps the most accomplished screenwriter and script doctor in movie history,” over the course of his career he won “the first Academy Award for screenwriting, won a second with his partner [Charles] MacArthur, and was nominated five other times.” ↩

Alissa Anderson is Associate Editor in the Office of Publications at Columbia University GSAPP and an editor of the Avery Review.