Thirty minutes outside of Chicago is an affluent neighborhood called Oak Park. To find it from the Loop you can take the “L” and go west on the Green Line toward Harlem. Cut your walk in half and get off at the Harlem/Lake station (not the Oak Park station). Now find your way to Forest Avenue and walk north for about fifteen minutes. At the corner of Forest and Chicago Avenues turn right and you will have arrived at our point of departure—the back entrance to the once home and studio of the prolific Wisconsin-born architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Peruse the bookshop, once a garage, for a moment. Our tour will start momentarily.

In fact, the tour started back on Forest Avenue. While you were carefully following my directions, you missed the front door to Frank’s house. Masking the entryway is one of Frank’s favorite games and it happens often throughout his early residential work. Your docent, one of the 650 volunteers employed by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, reminds you of this hide-and-seek processional as he leads you back to where you have already been. He is an older gentleman—tall, knowledgeable, and earnest. You learn that he has a background in art history and has written several books on Frank. 1 Move closer and listen closely; he knows what he is talking about. The tour begins like most stories about Frank tend to begin—first the man, then the work.2

For the first twenty years of his career, Frank called Oak Park home. He would later go on to have an affair in Italy, initiate schools in Wisconsin and Arizona, and spread his “American” architecture throughout the likes of Los Angeles, Japan, and New York, but for the sake of a one-hour tour and a casual tourist’s limited attention span our docent limits his speech to only Frank’s work in Oak Park. The first house Frank designed in Oak Park was the first house he ever designed. This is that house: a national historic landmark since 1976. Built in 1889 for Frank and his seventeen-year-old bride, Catherine Tobin Wright, the house is a refined example of the “vernacular Colonial tradition” (also referred to as Shingle style) and shows clear references to the works of Henry Hobson Richardson, Bruce Price, McKim, Mead and White, and Joseph Lyman Silsbee.3 Frank was twenty-two years old when he designed this house. At that time he was working for the Chicago-based architecture firm of Adler and Sullivan. It is well known that Louis Sullivan even loaned Frank the $5,000 needed to purchase the lot and build the initial house. It is also well known that The Master (i.e., Sullivan) would later fire Frank on account of the Oak Park houses, or “bootleg” houses, he was designing for neighbors and friends on his own time.4 According to Frank, he neglected to read the fine print in his contract.

Most, if not all, portraits of Frank paint him as a narcissist. And while our docent only hints at this characteristic in jest, it remains a valuable trait to consider when winding through the house’s pinwheel floor plan. Speaking to the house’s proportions in his autobiography, Frank writes that by “taking a human being for my scale, I brought the whole house down in height to fit a normal one—ergo, 5’–8 1/2” tall, say. This is my own height… It has been said that were I three inches taller than 5’–8 1/2” all my houses would have been quite different in proportion. Probably.”5 This distinctive measurement is made apparent from the outside of the house, where an exaggerated gable presses down on the west eave of the house like the brim of a low-riding baseball cap to conceal its wearer’s eyes—a shifty, but composed, effect. Inside, the vertical pressure is paralleled in the living room, where ornate beams lower the ceiling’s datum to guide one’s eyes through rooms and beyond. Only a few actual walls are visible. It is only at the hearth, or arched fireplace, that your vision is obstructed. Neil Levine, a Wright scholar, describes Frank’s use of conventional shapes, like those of the hearth and gable, as symbols of home. Here we see the beginnings of doubting Frank. He questions convention and approximates control over the vernacular representations of what constitutes a home. The experiment would take two decades to mature into what we now casually refer to as the “Prairie style.” It’s a slack title that only scratches the surface of a more robust ideology, much like “grunge” as a style of music. More persuasively, Frank refers to those symbols as giving the house a “sense of shelter” or to what Levine describes as “the projection of an image of shelter.”6 I believe the latter description warrants further review, and so after a quick walk-through of the famous playroom and Frank’s baptistery of a studio, I thank our docent for his time and withdraw from the group.

Before leaving Frank’s house, though, I pick up the Trust’s exceptional Architectural Guide Map of Oak Park and River Forest ($3.95 at the bookstore garage) to get a lay of the suburban grid. I begin my stroll south on Forest Avenue and am delighted to find a block party getting under way. The hot smell of barbecue and bare feet emanate from the pavement and I am reminded of a slightly more upscale version of a John Hughes film set. In the middle of the street, now car-free and blocked off by yellow tape, is an inflatable Slip’N Slide in the shape of a long arcade where several children are warming up for the day’s fun. Without my map, or among the twenty-or-so other tourists with maps, I may have been able to blend in and snag some brisket. Alas, I carry on and look down at my map.

Few places in the world compare to Oak Park’s concentration of essential architecture by a single architect. Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village at the University of Virginia, Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia, Borromini and Bernini’s Rome, are some other hot spots to consider on your travels. Beyond designing a home and studio for himself, Frank would go on to design more than thirty structures within Oak Park and its adjacent community to the west, River Forest. Of this architectural smorgasbord of Chicago common brick and oversize eaves, one of the most curious reminders to a visitor like myself is how inaccessible the rest of the work truly is. Fact: All but two of Frank’s structures (the Unity Temple and the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio) in Oak Park are privately owned. And for good reason, too; real people live here.

Of the many houses on Forest Avenue, Frank designed six. On Chicago Avenue he designed four. Three or four more houses on Euclid Avenue. Two houses on East Avenue—you get the idea. The map clearly states that “all the homes on this map are privately owned. Please respect the homeowner’s privacy and remain on the public sidewalks.” Thanks. Now that loitering in side yards and peering through windows is off limits, I consider my other options. The thought of ringing doorbells and introducing myself as an architect (or salesman) crosses my mind until I remember the block party. I would hate to disturb a day of rest. I concede that the closest I can get to any of these houses without tripping an alarm or signaling the neighborhood watch is approximately 50 feet, or as the Trust’s map denotes—the public sidewalk. For observing ancient Roman ruins this would not be too great an issue, but for houses that recede into the tree line like single-family low-profile castles, the only observation to be had is superficial at best and will require more inventive styles of vision. For now, I catch the L back downtown and consider my return.

Once a year the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust offers its Wright Plus Housewalk, a special tour for a select few to experience rare interior views of the Wright-designed private homes, which are typically off limits in Oak Park. As enticing as that may sound, there is a sense of democratic beauty in the limitation to the Trust’s aforementioned notice to remain on the public sidewalks. Foremost, it returns us to Levine’s notion of a projection of an image of shelter. For a projection to remain as such, keeping one’s distance is a good thing. More specifically, by limiting viewership to only what is viewable from the sidewalk, the houses might unfold differently than a typical walk-through, in which modern conveniences like through-wall mechanical units and attic fans assault the eyes. Also, considering the time that has passed since each of the house’s original construction, it is not uncommon to find many of the home’s secondary and tertiary façades altered: Garages have been widened to accommodate contemporary automobiles, additional flues tacked on for his and hers chimneys, new decks have been enclosed for the big Weber grill, and even a little cupola now pokes up through the roof offering a fuller view of the backyard. These are just some of the features to observe from anywhere other than the public sidewalk, and you can thank the Oak Park Historic Preservation Commission for masking such wonderful affectations. In their highly detailed Architectural Review Guidelines, a “yes” to any addition or alteration to the original house is usually coupled with the provision of “not visible from the street.” Like a hero best never to be met in the flesh, keeping to the sidewalk allows the houses to retain a sense of mystique, or strange authenticity; your imagination does the rest. Heroes are meant to remain heroes. Probably.

This practice of visual restraint can be furthered by coupling it with another medium, or view, to redirect one’s focus from the actual artifact to an even more idealized version: the drawing of the artifact. After all, the original drawings drafted by Frank and his staff of his Oak Park houses are likely to offer a clearer impression of what the works may have looked like, right? Keep in mind, however, this style of vision may also border on sterility were it not for the fact that Frank’s career was only beginning in Oak Park. The drawings of these Chicago homes are like sketches that would inform other plans, other buildings, and other, more familiar, interiors.

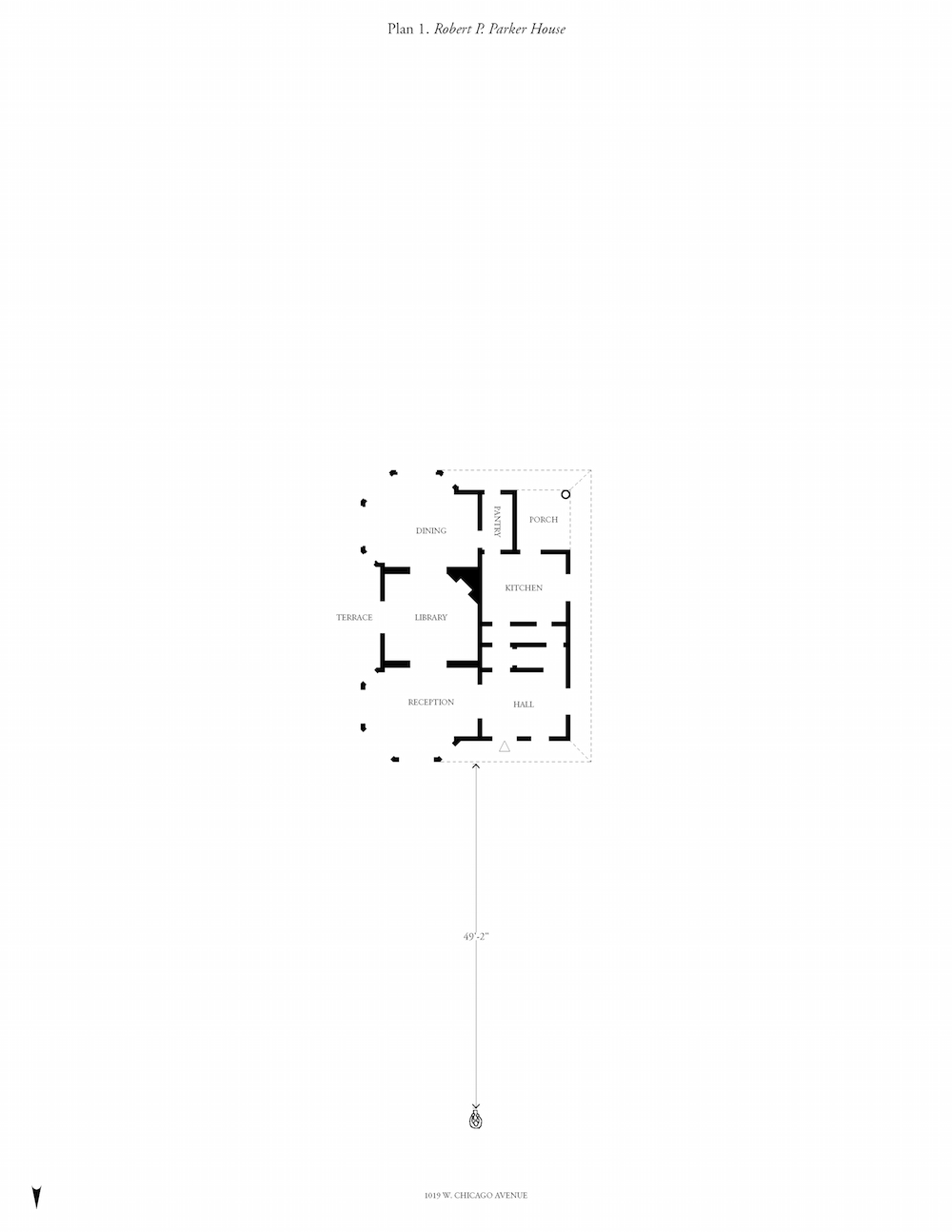

With the help of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, I have redrawn an addendum to the Trust’s map.7 For seventeen of the Oak Park homes Frank designed please see the following list of first floor plans that were made available by the archives. For the sake of consistency and comparison, each plan has been redrawn to a matching scale. In addition, repetitive graphic standards are used to indicate entry, roof line, program, wall thickness as well as each houses’ position relative to the sidewalk and your view. Feel free to couple this drawn record of Frank’s houses with what you see on your next walk through Oak Park. That said, be certain to begin your walk at Frank’s house. For fifteen dollars, no one will call the police.

-

The docent, Patrick Cannon, and his book, Hometown Architect: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois, serve as key first sources for this review. A warm thank you to Patrick for his wonderful tour of the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio. My apologies in advance for not doing it justice in this article. ↩

-

It should be noted that the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust’s employees, and most of his devoted followers, still prefer “Mr. Wright.” ↩

-

Patrick F. Cannon, Hometown Architect: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois (Portland: Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 2006), 15. ↩

-

Frank referred to these works as “bootleg” or “overtime” houses. Ada Louise Huxtable, Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life (New York: Penguin Group Inc., 2004), 62. ↩

-

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 1943), 141. ↩

-

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography, 142. Neil Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 10. ↩

-

A special thank you to Nicole Richard, Drawings and Archives Assistant at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. ↩

Thomas Kelley (M. Arch Princeton University, B.Arch University of Virginia) is a partner in the design and architecture collaborative, Norman Kelley, and a Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Architecture.