On the following pages, the National Lampoon presents, as a public service, a selection of “spoilers” guaranteed to reduce the risk of unsettling and possibly dangerous suspense... Psycho: The movie’s multiple murders are committed by Anthony Perkins disguised as his long-dead mother...

—D.C. Kenney, “Spoilers,” The National Lampoon, April 1971 (first mention of the world “spoiler” in popular media, at least according to that paragon of mediatic popularity, the Oxford English Dictionary)

We sort of play. But it’s all hypothetical somehow. Even the “we” is theory: I never get quite to see the distant opponent, for all the apparatus of the game.

—David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

Some months ago, frittering away in a social media farrago—I forget which one exactly—a fleeting mention was made of Another Earth (2011), Mike Cahill’s moody, atmospheric science fiction indie film, which I happened to confuse with a similarly titled film, M. Night Shyamalan’s not-so-indie After Earth (2013). I watched the latter, thinking it was the former, and well into it, realized something was wrong. Is that Jaden Smith? Didn’t he sing “Pumped Up Kicks (Like Me)?” I posted all of this on Facebook, and when one journalist friend replied that Shyamalan films “suck dangerously,” this prompted another friend of mine, also a journalist, to write, “He’s dead the whole time! And the village is in the present day! And the aliens can be killed by water! You must just have missed the subtleties. You’re welcome.”1

Along with subject headings and social media posts brandishing the letters “NSFW,” the spoiler alert (“SPOILER ALERT”) has become a kind of online lingua franca that capitalizes on the asymmetry of information. One person—the “spoiler”— knows something the other—the “spoilee”— does not, and moreover, is all too keen to make this imbalance known. As the above laundry list of “Shyamalan Twists” shows, the spoiler alert can be deployed for maximum comedic effect. We may not have seen these films, but we already know all about their respective, revelatory “twists.” It all makes sense with 20/20 hindsight, of course. Ever notice how Bruce Willis does not interact with anyone other than Haley Joel Osment? SPOILER ALERT: Bruce Willis’ character is DEAD! This is the equivalent of going into a restaurant, asking about the quality of the tuna tartare appetizer, only to have the server reply, “SPOILER ALERT: IT’S RAW.”

Criticism thrives on spoiler alerts and Shyamalanian twists. Technology is socially constructed! Nonhuman objects are actors! Modernity does not exist! The book has killed the building! We’ve heard these not-so-surprise endings, and our task is to figure out how they came to be. How is this done? You say “close reading,” I say “reverse engineering,” or as novelist Martin Amis characterizes the not very mysterious murder at the heart of London Fields (1989), “Not a whodunit. More a whydoit.”2 Moreover, such reverse engineerings still privilege authorial intent. To put it another way, the “spoiler” will always vanquish the “spoilee.” The latter is left with a cache of knowledge that was not wanted, but, you know, there are plenty of spoiler alerts for those spoiler alerts. Old saws like “curiosity killed the cat,” “you can’t unring that bell,” etc, tell us that it is the “spoilee” who desires this contraband knowledge in the first place. In short, reader and “spoilee” are complicit, yet neutralized. Hold on to that thought.

A spoiler alert to McLain Clutter’s excellent Imaginary Apparatus: New York City and Its Mediated Representations (Park Books, 2015) would probably go something like this: Mayor John V. Lindsay was in cahoots with the television and film industries while developing the 1969 Planning Commission’s six-volume Plan for New York City. Boom. That definitely just happened. But before you close the tab on this browser and tell yourself, “I think I know what this Clutter fellow is up to,” go to Netflix and watch any film recently shot in New York City. Should you make it all the way through the end credits, past the MPAA certificate numbers, IASTE and SAG/AFTRA seals, logos indicating that Panavision, Arri, or FotoKem equipment were used in a shoot, you will likely see a little badge saying “Made in NY” or “NY FILM,” signifiers for financial incentives given to film production companies to shoot in a particular borough. The practice of attracting on-location shooting is common nowadays; it offers civic officials an opportunity to monetize the image of a city by allowing production companies a tax credit in combination with relatively low permit costs. As revealed in Imaginary Apparatus, the Lindsay administration pioneered this practice while framing it—intentionally—in terms of its architectural and urban stakes. We are in the late 1960s, and in an era when New York was in the throes of ruination and blight, consecrating the image of the city to celluloid and nitrate was as important as committing it to concrete, steel, and glass.

He’s a clever one, that Clutter, formidable, weaving the stakes of his architectural analyses beyond their historical and theoretical figurations. The approach here is twofold, with each part occupying a separate section of the book. In keeping with the spirit of this essay, I’ll just tell you that, in one way, Part 1, “The Apparatus,” is dedicated wholly to explaining the book’s title. I’ll leave it at that for the moment and dwell on Part 2, “The City,” to give a sense of an ending. My reference to literary critic Frank Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending (1966) is intentional, and wholly fortuitous—for if you think about it, is not Kermode’s book a cosmic mediation on the spoiler alert? At least this is what comes to mind when he writes, “We project ourselves—a small, humble elect, perhaps—past the End, so as to see the structure whole, a thing we cannot do from our spot of time in the middle.”3 As accessories before the fact, we too notice the whole structure of the book, especially how Clutter ends Part 2 of Imaginary Apparatus with a three-part essay structure. A skillful, urgent reading of the plaza in front of Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building as a literal stage on which William Whyte surveys the public with 8- and 16mm cameras in “Spectator”; the visual machinations of “Desire,” especially as they vindicate the cultural and aesthetic politics of value-added urbanism in films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969); linking Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972) to the complex collusions between architects, planners, and systems theorists at the 1970 conference “Restructuring the Ecology of a Great City”: All of these touch upon a brooding omnipresence throughout the book otherwise known as “The Apparatus.”

With a name that calls to mind arch-criminal and rabble-rousing syndicates in James Bond novels and films (i.e., the Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion, or SPECTRE), comic books (HYDRA, from Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Strange Tales # 135 from 1965, or HIVE, the Hierarchy of International Vengeance and Extermination from 1980’s New Teen Titans #2), or cartoons (FOWL, the Fiendish Organization for World Larceny, from Disney Television Animation’s DuckTales), “The Apparatus” is Clutter’s portmanteau term that combines Michel Foucault’s construct of the dispositif with Marxist apparatus theory associated with film scholars Christian Metz, Jean-Louis Baudry, and Jean-Louis Comolli. “The Apparatus” takes top billing in Part 1 of Imaginary Apparatus, in which Clutter invokes how different individual and institutional actors parse knowledge and power and create subjects, as well as the complicity of capital-C Cinema in leveraging images for their monetary value. Add to this the term “Imaginary,” a direct reference to the Lacanian mirror-stage—the unattainable desire for an image of the “ideal self”—and we get a sense of what the author is getting at, for the “Imaginary Apparatus” in the book is really the complex skein of aesthetic, political, and financial interactions that made New York’s “mediated self” an important instrument of late 1960s urban design initiatives.

Scholars and historians have made short work of architecture’s media functions, claiming them as important, if not more so, as actual physical buildings. We scour through archives, dig up sketches, engravings, magazines, any kind of published format that proves architecture as being what the U.S. copyright statutes call a “tangible medium of expression.”4 Clutter’s Imaginary Apparatus is a welcome addition to this body of literature, making a case for the vitality of architecture’s image-ability. Yet as more on this topic continues to be written, as more and more obscure publications, drawings, or other ephemera are found that capitalize on the imagery of architects, architecture, and cities, we are left with an ineluctable sense that this emphasis on the circulation of images has become the sina qua non of architectural scholarship. Or rather, it has become the event horizon of a black hole of sorts—try and try as we might, we cannot escape the overwhelming gravitational pull of this media-based approach. And as for other logics, whether rooted in “global” or synchronic understandings of history, or culled from the methods of other disciplines, these still valorize re-presentation—in other words, those strategies that we see as alternatives to architectural history’s media-based methods are still, fundamentally, inexorably, mediatic.

Clutter also senses this, for at the very end of the book (SPOILER ALERT!), he reminds us how apparatus theory cedes neither “subjective agency” nor any “position from which to intervene.”5 This sets the stage for what is perhaps the most important—and subtlest—point to Imaginary Apparatus, that designers should embrace the “entrapments of apparatuses and spectacle” in their own practices. One the one hand, this may read as an outright concession, and for those readers out there who carry their intellectual campaigns in the name of “theory,” this throwing out of Foucault with the bathwater may amount to nothing short of heresy. On the other, this is a recognition that the image-ability of architecture cannot be undone, or to use Clutter’s own observation, that the ubiquity of apparatuses and spectacles demands their recognition more than ever. And though he admits that designers should not accept the totalizing scope of apparatus theory, there is little if no guidance on how to incorporate these ideas into design practice. So there we are, spoiled spoilees, wondering what to make with this scalding hot potato of an issue, deciding whether to hold on to it or to pass it off, to spoil it for another spoilee.

Clutter has not defanged apparatus theory; he has given it rubber teeth. And in doing so, Imaginary Apparatus opens up other avenues and possibilities of analysis and action. Consider, for example, how Clutter himself is performing—and transforming—the very object of his criticism. In his strident and effective formal analyses of frames taken from What Is the City but the People (1969), a documentary film made by John Peer Nugent and Gordon Hyatt in conjunction with the Lindsay administration, as well as of other films like Midnight Cowboy, and through an inspired study of the graphic layout and photographic strategies of the 1969 Plan for the City of New York, Clutter not only brings “The Apparatus” to life, but demonstrates how to think about it in architectural and urbanistic terms. This is what is referred to as working on the urban environment “through” its representation, of “moving through and reorganizing the interrelated and underlying interests, economies, and imaginaries composing contemporary urbanism to effect new aesthetic regimes, collectivities, and vectors of subjectification.”6 It may be asking too much to consider whether this prescriptive strategy avoids the neutralization of historical and theoretical analyses by transforming them into design projects. If—and only if—this is the case, then Clutter is here firing a parting shot, recognizing the necessary burden architectural scholars and practitioners must assume in understanding the stakes of their project before they unring that bell and become spoiler instead of spoilee.

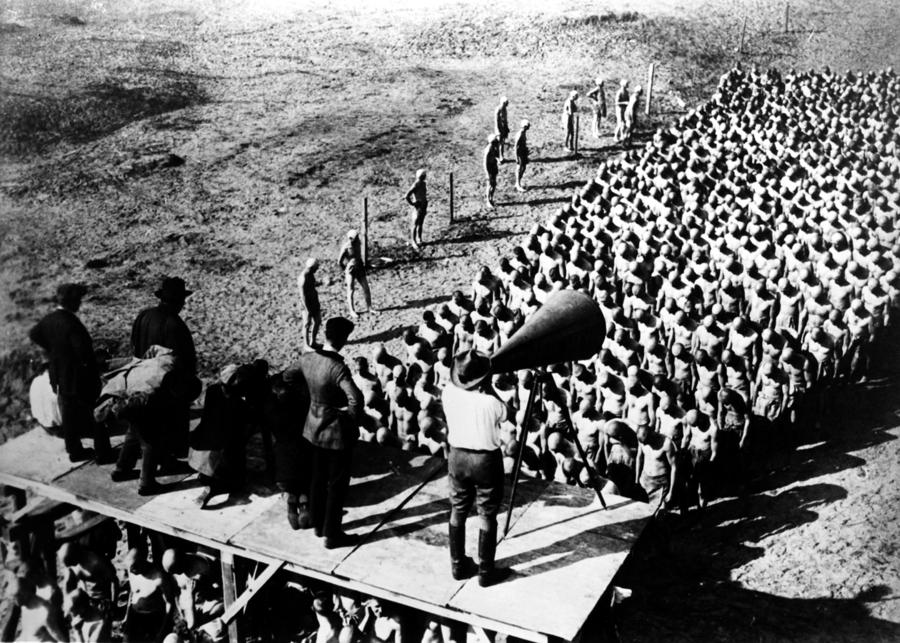

In these final moments, as this essay moves away from the sense of an ending to the end itself, I offer an image that encapsulates what is at stake in Imaginary Apparatus. It is an aerial photograph taken during the making of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927):

Readers may recognize what is happening in the image: Lang is atop a scaffold, directing the extras who will appear in the “Tower of Babel” scene. This scene occurs at a critical point in Metropolis, when Maria narrates to a group of workers the story of the Tower to emphasize the disunion between the head (the upper management of the film’s titular city) and the heart (the workers toiling underground). In this image from the making of Metropolis, the extras’ heads are bent, although it is not clear whether it is to shade their faces from the sweltering sun or if they are rehearsing. Similarly, Lang, flanked by film crew, in shirtsleeves with wide-brimmed hat, doing his best D.W. Griffith, yelling into a giant megaphone, appears not so much as a director, but rather as a high priest or overseer, telling the phalanx of shaven heads what they are supposed to be doing. This confusion between image and reality also applies to the Tower of Babel, which is to be read as the allegorical ancestor to the modern corporate skyscrapers appearing throughout Metropolis. It all points to the indelible comminglings of powers and institutions, of art and commerce, and to the deliberate framing and articulation of cinematic subjects.

The image also appeared on the cover of the first edition of Pam Cook’s The Cinema Book (1985), and at one time, so we now understand, was proposed to be on the cover of the first edition of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996).7 That novel’s dramatic and filmic connotations are clear. Not only is “Infinite Jest” a reference to a line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, but it is also the name of a movie directed by James O. Incandenza, one of the novel’s central characters, whose films were “such that whoever saw it wanted nothing else ever in life but to see it again, and then again, and so on.”8 Viewers cannot stop watching the film and will die doing so. And though “The Apparatus” is not a deadly thing—remember, this is a theoretical construction with rubber teeth—this idea of Wallace’s manages to resonate because it aligns with the totalizing nature of the apparatus. Just as viewers are caught in an unending recursive loop of infinite viewings of “Infinite Jest,” the subjects in apparatus theory are, like poor Yorick’s skull, passive, powerless, spoiled. The point of Infinite Jest is that the way out of the recurring imagery relies on agency and choice... which reminds us of the call in Imaginary Apparatus to consider media as “authored, as opposed to received.”9

And in case you’re wondering: Anna Karenina is run over by a train, “Rosebud” is a sled, and the “Sea Monstah” is a sunfish.

-

The exchange, from August 2014, was between me, John J. Edwards III, a writer for the Wall Street Journal, and Todd Pruzan, an editorial director at Ogilvy & Mather. ↩

-

Martin Amis, London Fields (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 3. ↩

-

Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction (1966; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 8. ↩

-

17 U.S.C. § 102(a). ↩

-

McLain Clutter, Imaginary Apparatus: New York City and Its Mediated Representation (Zürich: Park Books, 2015), 186, 191. ↩

-

Clutter, Imaginary Apparatus, 192. ↩

-

David Lipsky, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace (New York: Broadway Books, 2010), 95, 313. Wallace’s personal copy of the book is available at the Harry Ransom Center for the Humanities. See Molly Schwartzburg, “Infinite Possibilities: A First Glimpse Into David Foster Wallace’s Library,” Cultural Compass, March 8, 2010, link. ↩

-

David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (New York: Little, Brown, 1996), 548. ↩

-

Clutter, Imaginary Apparatus, 192. ↩

Enrique Ramirez teaches architectural history at Ball State University’s College of Architecture and Planning and is an advisory editor for Manifest: A Journal of American Architecture and Urbanism.