Prior to her first solo museum exhibition, Laura Poitras was known—if she was known at all—as the maker of meticulous and engaging documentaries. Her “9/11 Trilogy” included My Country, My Country; The Oath; and culminated in the Academy Award–winning CITIZENFOUR, in which the viewer literally got in bed with Edward Snowden as he carefully guided us through all sorts of government malfeasance, secrecy, and all around chicanery. This highly intimate documentary showed Snowden laying out various government surveillance programs and moved at a dizzying pace, as if the world and CIA were going to collapse onto the film itself and bring the whole thing to an end. CITIZENFOUR placed Poitras, along with journalist Glenn Greenwald, next to Snowden as the protagonists of the film. Oftentimes, it seems, Snowden is merely a vessel, channeling the American government’s darkest secrets through Poitras’s camera and Greenwald’s pen out into the world. For those who read Greenwald’s accounts in the Guardian or watched his many appearances on cable news, CITIZENFOUR had a comfortable, behind-the-scenes air.

Poitras’s films are both delicate and confounding: delicate in subject matter and the obvious care she takes in crafting a narrative and confounding for illuminating the seemingly endless extents of governmental secrecy. As a viewer, you are continually struck by her incredible access and the quiet objectiveness she shows towards her subjects. She is both central to the story yet rarely heard and almost never seen. Poitras is clearly a gifted and dedicated filmmaker who has earned many accolades and acquired a loyal fan base, a Venn diagram of which might include committed documentary viewers and those re-watching the entire run of X-Files in eager anticipation of the show’s much belated revival. I would place myself in the center of that Venn overlap, making me an eager viewer and easy target for her museum exhibition.

For her exhibition, titled Astro Noise—which “refers to the faint background disturbance of thermal radiation left over from the Big Bang and is the name Edward Snowden gave to an encrypted file containing evidence of mass surveillance by the National Security Agency”—Poitras was granted the top floor galleries of the newly opened Whitney Museum.1 The entire floor is little more than a small series of reconfigurable rooms that compete only with the museum coffee shop for attention. This level, it should be noted, is the only one that showcases Renzo Piano’s trademark museum daylighting, an amalgam of intense technological detailing and old fashioned, saw-tooth knowhow. Poitras, however, required none of it, and judiciously redacted all hints of daylight from the exhibition space. I’d like to think that covering up the windows was a subtle critique of government secrecy (if not the museum’s architecture)—that Poitras is creating a black box, into which she will invite us in order to reveal The Truth. Or maybe she will at least reveal some potential gaps in that truth, and the extent to which a tension between secrecy and surveilance continuously surrounds us in banal ways. In either case, she will allow us in, and after she does, we will come away either more enlightened or more furious (or, more likely, both) regarding our own government’s most nefarious practices. The cool glow of a museum projector will hopefully disinfect what the sunlight cannot.

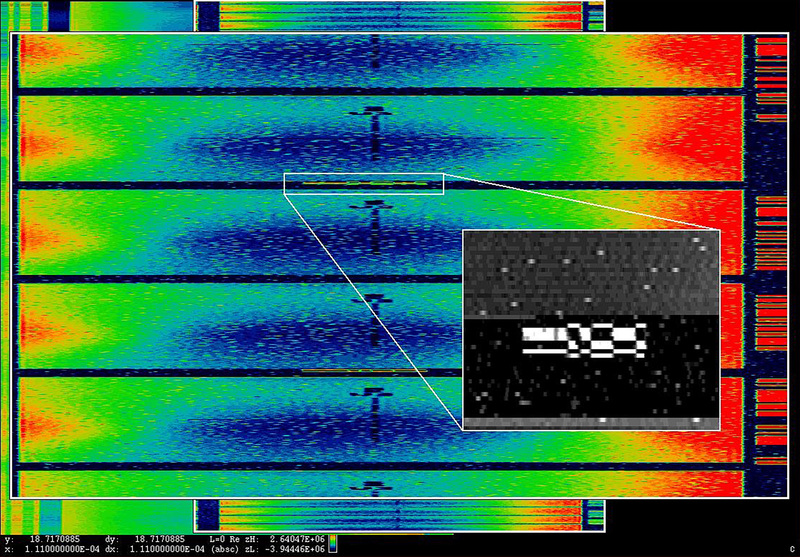

The exhibition is an intimate collection of works, five to be exact. A series of abstract digital prints—a selection from her ANARCHIST series—greets the visitor on the outside of the galleries. The images are drawn from the Snowden archives and are nonrepresentational images from a UK communication station located on Cyprus. They verge on television test patterns or static, and some have vague outlines of moderately intelligible shapes. It’s hard to tell if these images are themselves scrambled, reconfigured, or just low resolution. Perhaps a combination of all three.

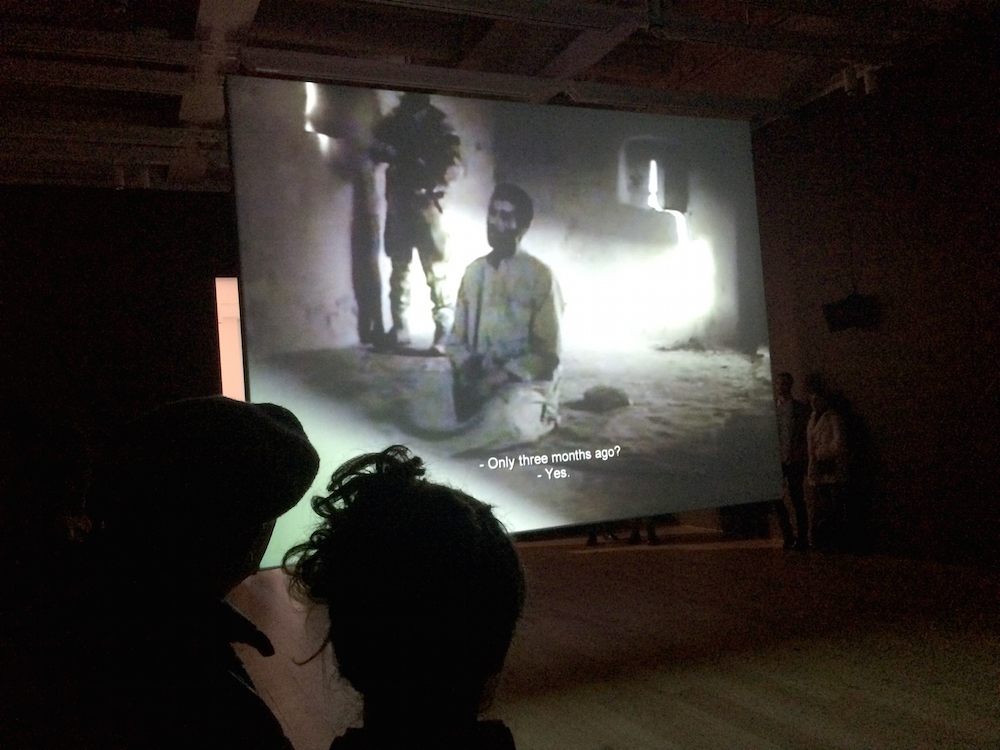

Displayed in the first gallery is O’Say Can you See, a double-sided projection. On the first side Poitras projects faces of unwitting visitors to the Ground Zero site of Lower Manhattan shortly after 9/11. The video is played in slow motion showing a broad swath of visitors, some looking idly at the wreckage of the World Trade Center, others showing more emotion, others yet not paying much attention at all. The video is a precursor to the “reaction shot”, a video of people watching things, usually other, more shocking videos, and has now become common internet cliché. On the opposite side she projects an interrogation of Salim Hamdan in a non-descript location. Hamdan was an Al Qaeda driver and lent his name to the landmark Supreme Court case Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which ruled that the Bush Administration’s military tribunals were in violation of the Geneva Convention. He was the subject of Poitras’ second installment of the 9/11 Trilogy, The Oath, and the footage is an extended version of the clips she used to open the film. The soundtrack to both is a stretched rendition of the national anthem, performed at Yankee Stadium during Game Four of the 2001 World Series. The specific notes of the anthem are undecipherable but provide a sufficiently haunting soundscape that pairs well with the slow motion frames of the Ground Zero visitors, if not the interrogation. The stretched time-scape serves to illustrate the temporal schizophrenia that many of us felt on September 11—the feeling that the world had at stopped spinning and yet was hurtling toward oblivion at the same time. As a curatorial gesture, it also serves to smother the interrogations with the deadly spectrality of the American State.

Yet matching the two videos only makes sense when read through the explicitly didactic framing of the exhibition. The events are intimately linked but the link is a highly complicated one. By forcing them together on the same surface, the temporal lag between cause and effect is lost to a more ham fisted narrative suggesting blame and ignorance. The attempt to link tourists gazing over the wasteland of ground zero to the interrogations of Afghani men is easy to make, yet hard to comprehend. There is a sense of complacency being forced into the juxtaposition of interrogation and viewership that is at once reaffirming (true, we are all—at least if we are American—to blame for George Bush and his post-9/11 actions) and maddening (but must we take credit for Dick Cheney and his “dark side” too?).

The most successful piece in the show is Bed Down Location, an immersive environment in which visitors are invited to lay on their backs, gaze up at the night sky, and listen to the sounds of drones and other static buzzing above. The images of evening sky rotate between Yemen, Somalia, and Pakistan—where drones are deployed—and the Nevada ranges where they are tested. The drones themselves can only be heard, their terrible noise being part of a complex sound installation mixing various drone recordings with pilot’s voices and other radio interference.

Susan Schuppli has written on the inescapable violence drone warfare has on entire populations. Unlike the supposed precision of the drone’s strikes, their constant buzzing targets large territories creating a totalizing environment of fear. Quoting a Stanford/NYU report, Schuppli notes, “One man described the reaction to the sound of the drones as ‘a wave of terror’ coming over the community. ‘Children, grown-up people, women, they are terrified…. They scream in terror.’”2 Sonic warfare is a tried-and-true tactic. The Bush Administration itself recognized the power that loud music, noise, and screaming babies had in making prisoners talk—or at the very least, keeping them awake, which would later make them talk.

Bed Down Location attempts to recreate an environment of creeping terror, though within the context of a major American museum, the charge is a near impossible task. But it is one that should certainly be attempted, if for no other reason than to counter the dominant narrative that drones are silent and unseen (or in defense-speak, “effective”), when in fact they have a very real, material, and aural presence within the populations they continuously surveil.3 Beyond the common complaints that can be levied against any exhibition—primarily overcrowding and less than interested visitors, given the many visitors who seemed to relished the chance to lie down, if not to experience drone warfare—recreating a sense of complete precariousness is difficult within the embrace of the museum walls. But the feelings of personal safety afforded by museum walls can be operative in generating a type of sublime connection that outright fear never can—which is to say that the spatial and institutional reality of the exhibition can be what actuates the critical point of view that Poitras is hoping to present. This tension is not uncommon to critical museum projects, but it also could have been useful for the formal and experiential discourses Poitras is attempting to situate Astro Noise within. Laying down and gazing upon the digital sky, it was hard not to think this singular piece would have been perfect in the old Whitney ground floor project room. It is self-contained and highly legible, and its inclusion with other, far less successful works serves only to lessen its impact.

Part B of Bed Down is located near the exit, where a screen shows the “drone’s eye view” of the installation room. The visitors are shot with an infrared camera and appear as white-hot blobs reclining on the platform and milling about the room. This is at once a powerful reminder of the dual nature of drones—that they have a point of view, but one that is inherently anonymizing—and an Instagram-destined one-liner.4 (In another nod to gimmicky marketing, the bookstore includes postcards that read, “Dear visitor, your attendance at Astro Noise has been permanently recorded.”). In real-time, the Bed Down infrared video elicits a certain fetishized image of drone surveillance, while simultaneously driving home the treacherous moral landscape in which the entire drone program sits. Here people are not necessarily people, they have been reduced to a data stream that only accounts for basic biological functioning. This is the same reason it makes such great Instagram fodder—it is both beautiful and anonymous, intimately voyeuristic and clinically sterile.

Between the two parts of Bed Down Location is a hallway containing Disposition Matrix, a series of cubby hole–like slits in the wall. Behind each small window resides a copy of a government document, a video, or maybe a drawing. According to the exhibition handout, the Matrix refers to “the database created by the White House and American intelligence agencies as a blueprint for tracking, capturing, rendering, or killing people they suspect are enemies of the U.S. Government.” It’s hard to know what the curatorial direction was in gathering these documents, perhaps twenty in total. The most direct connection between them is that they all pertain, in some way, to the so-called War on Terror, or more broadly, to the post-9/11 security state. Behind one cubby is a drawing of a waterboarding platform. Behind another, drone footage. And behind yet another, a letter from the former CIA director George Tenet, concerning NSA guidelines for collecting information on foreign computers.

As Poitras notes, the documents are intended to “evoke a notion of the deep state,” a type of shadow government, or perhaps the real government, that is involved in torture, drone war, disappearing people, and the general horrors of death and war and keeping the world in check. The deep state is purposefully impenetrable—it’s the guy holding the black marker, it’s where Frank Underwood rules, and Mulder and Scully eke out the truth. I imagine it like the deep web, with just as much pornography and even less oversight. But like any bureaucracy, even the deep state leaves a paper trail, one that reaches past the exhibition materials into the thousands, perhaps millions, of pages.

Knowing this, or at least making a solid intuitive guess, the curatorial arrangement of the documents is hard to negotiate. The formats, content, and temporal arrangement have been scrambled. This is generatively discomforting in that it recreates an assemblage of interconnected state administration. But if Poitras is attempting to create a “narrative experience,” as she claims in the exhibition catalog, that narrative is fragmented and hard to follow.5 Each document is presented as one needle in what is presumably a vast amount of hay. But there is a lurking sense that in the end, there are no needles—it’s all just hay, and we’re left to sort it out. This is likely an appropriate representation of the process Poitras went through in creating the exhibition and selecting the documents—looking at thousand of memos, trying and failing to make meaning between them, and filling in the gaps, or at the very least highlighting them. An installation about those gaps and about the discontinuous, multivalent state that produces them would provide a coherent means to register an inherently incoherent subject. Instead, what we are left with is a seemingly random selection of materials that represents a deep state that is startlingly like the shallow state—one that runs on a lot of meetings and administrative memos.

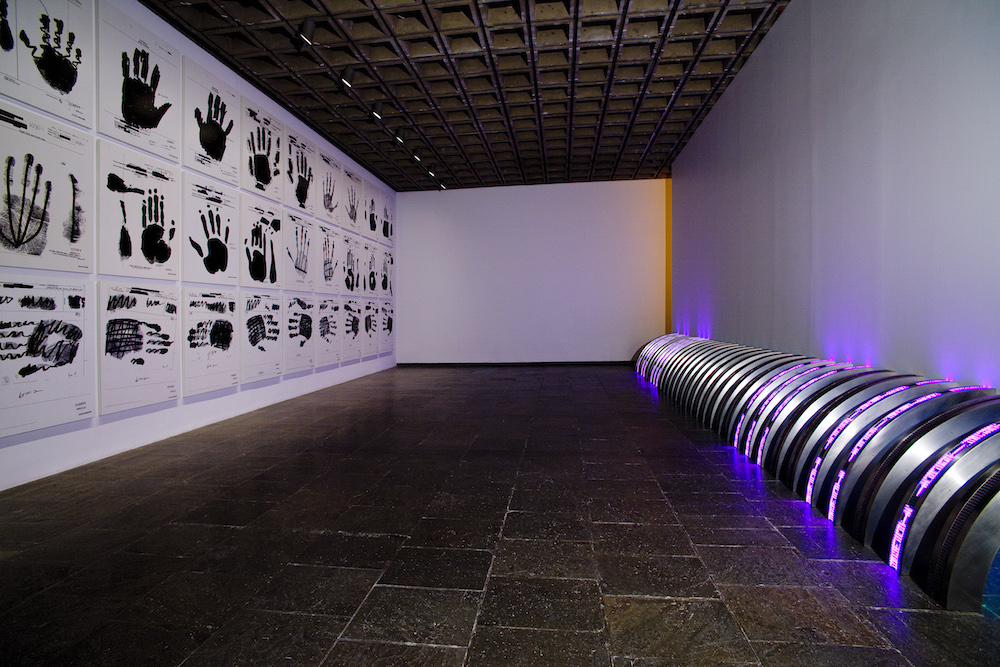

The final project is Poitras’s most personal and in many ways her most tightly packaged. November 20, 2004 consists of a series of redacted documents enlarged and displayed on lightboxes with a companion video. Through the piece we learn that Poitras was added to the government’s watch list in 2006, and after years of being detained each time she entered the U.S., she filed a Freedom of Information Act request to find out why. While heavily redacted, the documents reference her presence on an Iraqi rooftop shooting film. The government never actually asked to see the film she shot, and so, along with the documents gained through the FOIA, she displays the entire, unedited film. It’s not much—Poitras peering down on an Iraqi family, shots of an American military convoy passing by in Humvees—but the tightness and narrative arc of the project is coherent. Through the piece Poitras is calling out the government’s ineptitude, its hostility to journalists, and its tendency to sweep with a broad net without the resources or interest to cull the catch. It is also a stark reminder of just how far-reaching the aforementioned deep state can penetrate. The documents are proof that there was an investigation into her presence in Iraq and yet the investigation stopped short, leaving her in a bureaucratic limbo wherein she would forever be detained each time she entered the country, but the particular reason why need not matter.

Poitras’s work, and more specifically Astro Noise as a series of artistic projects, fits into what art historian Pamela Lee describes as an aesthetic of secrecy. This is an aesthetic that spans from CCTV footage to RAND Corporation white papers. It is a rich set of material and conceptual constraints, one that has been successfully mined by the likes of Julian Assange and Mark Lombardi. Two of Poitras’s most prominent contemporaries in the field are Jill Magid and Trevor Paglen. Both have a rich history of using surveillance technology to get at the intimate and hidden pleasure of revealing secrets and both are contributors to the museum catalog.

Magid’s Becoming Tarden project is a conceptually rigorous and multi-dimensional piece evolving out of a months-long residency with Dutch secret service, known as AIVD (Algemene Inlichtingen—en Veiligheidsdienst). The work resulted in a novel, yet one that was fully vetted and heavily redacted by AIVD sensors. The Dutch government felt the material so sensitive that during its exhibition at the Tate Modern, they reduced the book’s display to two pages encased within a glass vitrine. And at the end of the show, AIVD quickly confiscated the book lest it make its way to the museum’s archives or a collector’s storeroom. The performative aspect of the project uses redaction and government secrecy not as an object for display but as the method of creation, showing that the Dutch government is willing to both fund artistic works and censor their display.

Paglen’s work spans many such engagements with statecraft, whether mapping CIA rendition flights or using high-powered telescopic lenses to photograph government facilities like desert airstrips or remote surveillance stations deep in the mountains of West Virginia. The results are often sweeping references to the rich history of American landscape documentation and the peculiar expansive remoteness—the “covert sublime,” to use Lee’s phrase—of various government facilities. The subject in much of Paglen’s work is not the secret prison or the telecommunications satellite but the act of surveillance. On display is the lengths he will go to show what amounts to satellite dishes, small buildings, or streaks in the sky, which is to say, to show nearly nothing at all—small flecks of light and industrial buildings that have created a totalizing surveillance environment capturing the entire world.

All of these projects are predicated on what Lee calls an “open secret,” as opposed to an actual secret, which in the case of representation is highly important. None of these projects proposes anything that is really classified or unknown, rather they are working to represent the known unknowns (to use Rumsfeld’s famous axiom), that is things we know we don’t know.

In this case, the act of redaction, or a visualization of the unknown, becomes integral to the process of making artistic work, and even more crucial to the spectacle of viewership. The reveal, as it were, does very little in terms of displaying actionable or useful information. In other words, releasing a redacted document serves the government’s goal of adding less information into the stream as opposed to more. This type of non-reveal shows just how much is unknown and allows the deep state to circulate in a foggy ether just below the black box. In this sense, what the FOIA request does is not shed any more light on the government, but works to obfuscate just what the government does and why it does it. A redacted document begs more questions than it answers, especially when it is presented as a document but within and highly orchestrated museum exhibition.

Prior to the opening of Astro Noise, Poitras sat down with New Yorker editor David Remnick. Remnick asks her the most maddening question possible, whether she is concerned about aestheticizing either the “horror” of her subjects or the journalistic process she undertakes in documenting them. Poitras answered in the only way she could, by claiming she wasn’t, and that in fact she was attempting just the opposite—that she is trying to make people “not numb to information.”6 In a time when data, even much of the data on display, can be accessed with a little bit of internet and whole lot of fortitude, the quest to make data meaningful is a heroic task, and one that Poitras is certainly up to. But more importantly, the question of aesthetics remains pivotal not just to the work of questioning government secrecy but also the practice of hanging museum exhibitions. It seems clear why a desire to aestheticize violence and the suffering of those being continuously harassed by drone flights would be particularly misplaced. But by placing these works (with their noble desire not to aestheticize) in the context of artistic production and on the walls of museums, the battle over aestheticization has already been lost.

Jenny Holzer, for instance, took similar documents and created her Redaction Paintings in 2006. Like a collaboration between Michael V. Hayden and Kazimir Malevich, Holzer’s painting also hung on the walls of the Whitney. The subject of Holzer’s paintings were similar—the War on Terror, secrecy, and torture—and those points were easily legible. But so too was the fact that the paintings themselves, which is to say, the documents they came from, were engaging simply at an aesthetic level. The black boxes were both strategically placed and suggested a type of Pollock-like happenstance opening them up to multiple readings. Like Poitras’ exhibition, the Redaction Paintings embodied a legible political ideology, but they were hung as works of art. And as such, they could be engaged with as works of art. But in contrast to Astro Noise, the terms for engagement were left productively unclear by their very clear contextualization as works of art.

In Poitras’s pivot away from the aesthetic allure of her source material and the sublime magic of government secrecy, she is missing an opportunity to engage with the work at a much more affective level. Referring to the catalog again, Poitras points to the French filmmaker Georges Méliès as reference point for how his films both document reality and create “magic and fantasies.” Paul Virilio too uses Méliès in theorizing the “black out” or the “in-between state” created by cutting and reconfiguring film. According to Virilio, these discontinuous states created an “effect of reality that was radically modified.”7 Such effects can trick the audience, subverting the temporal logic of film—in Virilio’s terms, making new forms of reality visible.

At a more granular level, all film is broken simply by the means of its creation. The break between frames creates both a missing scene that structurally and narratively brings the medium together and a space of infinite possibility. This “picnolepsy” creates an automatic and continuous conscious time. To make the metaphor explicit, the frame divisions—the black bars, as it were—are structural and aesthetic cousins to the redacted text and the open secret. As such, they become not just sites for possible intervention, but potentially the sites for intervention and the points at which the secrecy and the deep state can be intensely interrogated. The power of Poitras’s prior work is that the process of interrogating missing scenes is seamlessly rendered within her films. Once the structure of experience migrates from film to museum, the means of interrogation beg different material and formal registers. In Astro Noise, secrecy’s aesthetic qualities were not attacked, questioned, or conceptualized beyond their logic of withholding state secrets. Within the museum, these practices take on a new valences, ones which allow both the artist and the viewers to learn something about how the materials were created and what, as a collection of curated works, they might signify.

It is difficult to say where Astro Noise will fit into Poitras’s career or her burgeoning artistic oeuvre. But by negating the aesthetic value of these works, they appear little more than one-liners without a strong thematic thread. Magid and Paglen have managed to become successful artists not just because of the rigorous conceptual framework of their projects, but because they engage in the aesthetics of artistic production and place their work firmly within the world of artistic practice. Poitras’s work stands as an important exposé on the ways in which the US government deploys warfare technology into everyday life. And her films testify to her rigorous process and adept handling of the medium. But the problem of how to ask the complicated questions she raises within the confines of an art museum needs to be addressed with the same level of rigor she deploys into the medium of film, and with the same passion and respect she lends to her subjects. Without an engagement at such level, we might as well just load the Guardian and get the full story from Greenwald or better yet log into Netflix and relax a little.

-

Whitney Museum of American Art, “Laura Poitras: Astro Noise,” link. ↩

-

Susan Schuppli, “Uneasy Listening,” in Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, ed. Anselm Franke and Eyal Weizman (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014): 381–392. ↩

-

Recently former CIA Director Michael V. Hayden made a plea for us to “embrace” drone warfare in order to keep America safe. He opened his editorial with a fabricated dialogue amongst drone supporters and doubters. Spoiler alert: the doubters were misinformed weaklings and the supporters managed to kill all the bad guys while keeping any and all civilians safe. See Michael V. Hayden, “To Keep America Safe, Embrace Drone Warfare,” New York Times, February 19, 2016, link. ↩

-

For a collection of infrared images (and others) taken by exhibition visitors see the Instagram pictures tagged with #astronoise, link. ↩

-

See Jay Sanders’s interview with Poitras in the exhibition catalog introduction. Laura Poitras, Jay Sanders, and Ai Weiwei Astro Noise: A Survival Guide to Living Under Total Surveillance (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2016). ↩

-

“Laura Poitras and David Remnick Visit the Whitney Museum,” New Yorker podcast, February 8, 2016, link. For the discussion on aestheticization skip to 9:18. ↩

-

Paul Virlilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance (New York: Semitext(e), 2009). For Virilio’s discussion of Méliès see pages 25–27. ↩

Jordan H. Carver is a contributing editor to the Avery Review and a Henry M. MacCracken doctoral fellow in American Studies at New York University.