The following essay will appear in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, published this spring by the Avery Review and Lars Müller Publishers.

An excerpt from Philippe Rahm’s Météorologie des sentiments (Les Petits Matins, 2015), translated by Shantel Blakely. Read Blakely's essay on Rahm's collection of stories here.

The temperature in the room is glacial. A cloud of steam forms in front of my mouth at each exhalation. I must undress before retiring but, apprehensive about the cold that will surely seem even more vivid to my naked body, I lack the courage to make the first move. Staying at my friend's house, I have been ill for several days, feverish. Snug in bed, under the covers, I continue to be cold. We have turned the heater on the wall to "maximum," but it does nothing.

It is impossible to elevate the air temperature in the house above 16 degrees celsius [60 degrees fahrenheit]. Aside from the astronomic, seasonal reason, there is the inclination of the axis of rotation of the earth, which determines that for part of the year, in winter, the Northern Hemisphere will be farthest from the sun. Because of the lengthening of distance between the Sun and the Earth, the latter receives weaker rays. The freezing polar currents descend into more temperate latitudes and cool the ambient air below zero. At the same time, this inclination of the north-south earth axis is responsible for the reduced length of the day. The sun rises later and sets earlier, which shortens the warming period and, by the same token, diminishes the quantity of energy the earth receives during the day. The winter nights become so long that they deplete the earth of whatever feeble warmth it may have acquired in daytime. There is also an intermediate reason, proper to the mode of construction of the building and relative to its poor thermal insulation coefficient. In the absence of supplementary insulation, the walls of the house are exposed concrete (which perform this task poorly). The house is effectively plunged in a bath of freezing air that crosses the small dimension of the walls, bit by bit, to radiate negatively toward the interior and cool everything. The little radiator on the wall, whose electric resistance draws in the air to blow it out reheated, is powerless in the face of the enormous mass of cold that encircles our living space.

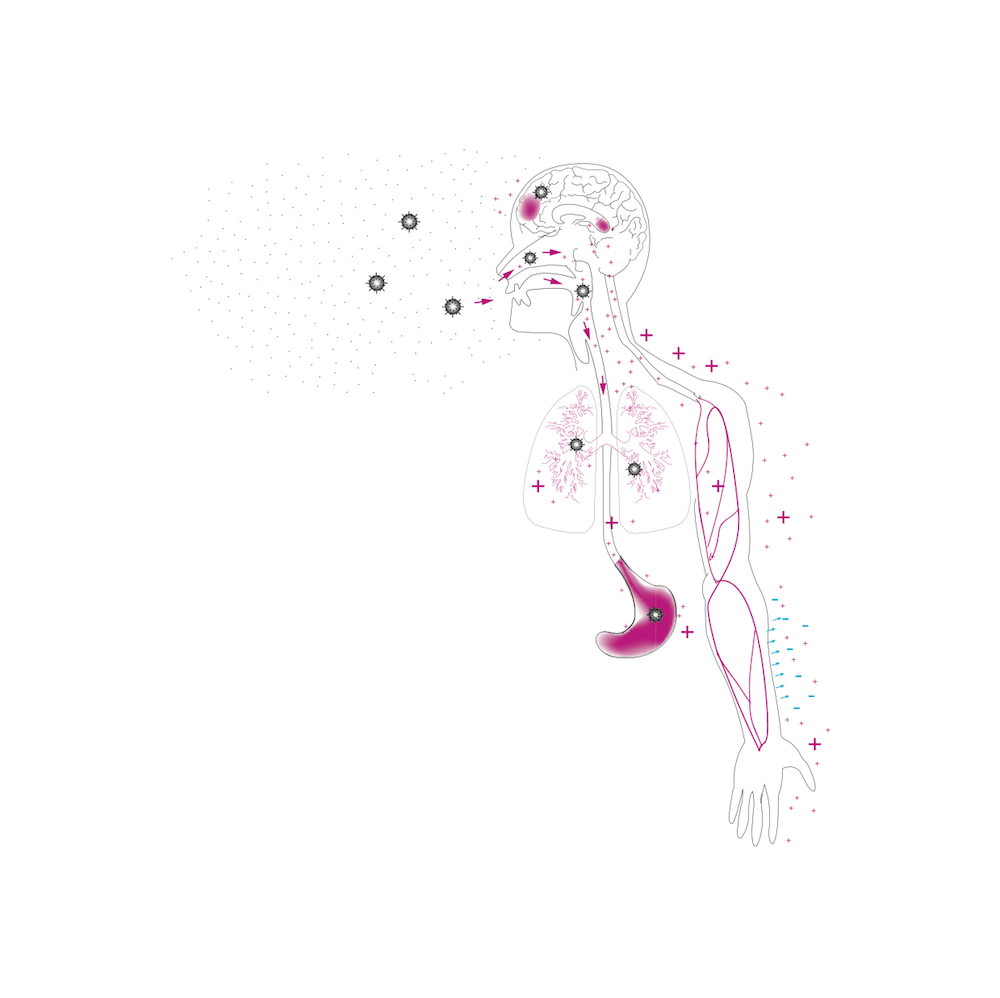

I had arrived in Japan a week before, at the height of winter. I was badly dressed but nonetheless stayed outdoors for the first few days, venturing into the cold in my cotton undershirt under a fine wool pullover. My body temperature was lowered constantly during the first day and, despite an accelerated combustion of protein in my stomach to compensate for this drop in ambient temperature, I was unable to keep my body from cooling to the threshold where bacteria and viruses could enter without resistance. I nevertheless tried to rebound in the course of the two following days. I adopted the multiple, dissociated, and circumscribed modes of heating that one finds in Japan: drinking warm tea; plunging my body in a hot bath; placing in my pockets, my shoes, against my back, small tissue paper packets containing a material that warmed up when rubbed. I had bought myself a coat but at no great expense and without great results; it was wool, but the absence of a lining and the imprecise mode of closing by three buttons on the front could not really generate an air pocket impermeable to the air and thermally isolated in which my body could be protected from exterior cold. I had also bought a black woolen hat—efficacious but insufficient to compensate for the inefficiency of the rest of my gear. For two days, I intermittently entered shops to heat up, and I took taxis and subways, perpetually seeking the warmest spatial pockets where I could hope to lay down my arms for a few moments in this physiological struggle of my body against the cold. I toured the Kyoto area, visited temples in the snow, crossed dewy forests, walked on icy paths in small shoes. I was accompanied by a friend and two young Japanese women he had met in Tokyo and invited to spend a few days at his home for the New Year. He confessed that he hoped to have an adventure with one of them. I flirted with the other one without asking myself if I really liked her.

After a day spent in bed following these two days of tourism, the fever has fallen slightly but I continue to feel the cold inside me; it is impossible to get rid of and I never invested in a better coat. My new Japanese friend invites me to spend a few days at her home in Tokyo. Seeing a means of escaping from this refrigerated mansion, I accept with pleasure. We take the train to Tokyo in the morning. After an afternoon in the city, we arrive at her parents’ small, ordinary Tokyo house. Her mother welcomes us kindly in the main space, whose dimensions she encloses around us by pulling two sliding panels. It is cold here too. The wood-and-paper walls seem ridiculously thin and totally inefficacious against the rigors of winter. I notice that there are no radiators except for a single, small, nonfunctioning space heater against the wall.

A short time later we sit on the floor, passing our legs under a low table whose feet are surrounded by a quilt. I have the pleasure of discovering that it is warm underneath: an infrared lamp, protected by a metal grille, is attached to the table’s underside and radiates agreeably on our legs. My friend brings out a second infrared lamp, on feet, which she switches on and aims at our faces. Her mother serves us food. We are now in a complex climatic condition: my legs are warm, almost too warm. The left side of my face receives the infrared rays of the other lamp and is heated, while the right side of my face and body, except for my back, remains cold because the air itself in this space is not heated at all.

The only mode of heat in the room is the pair of lamps, which, by direct infrared radiation, heat only exposed skin and clothes, without elevating the temperature of the room air. For this reason, steam rises from everything that was warm: my cup of tea, my bowl of soup, my friend’s mouth, reddened by infrared; her mother’s mouth, and mine, from which steam passes in front of my eyes at every breath, blurring my vision. The meal appears to me clearly to be a form of complementary heating (which it is, in fact, since it provides nutrients that are burned in the stomach and transformed into energy for maintaining our homeostatic metabolism at 37 degrees celsius [98.6 degrees fahrenheit])—one that is distinctly tastier than an electric radiator and releases a wider variety of aromas than a wood fire.

After dinner, I am effectively warmer. I hold in my hands a cup of steaming tea that I lift regularly to my face to drink a mouthful or to feel the radiant heat once again on my jaw. We stay a moment more in this room, then my friend takes me to her room, which she will lend me for the night. It is colder still, but she shows me how to turn on the heated mattress of her bed and how to regulate the temperature. Here, too, the experience will be one of sleeping practically outside, in full winter, but in a bed heated from inside, and happily protected from the wind and snow by the roof and the wall cavities. It is the opposite of modern Western heating, which raises the air temperature of a room to a comfortable level at which one breathes warm air. Here, the air breathed stays icy and it is only against the body, in the body, at specific, circumscribed places, that heat is applied.

I am on my feet, hesitant to undress. It occurs to me that I must still go to the toilet, which is at the bottom of the wooden stair. I leave the room without closing the door, perhaps imagining that the heat of my cup of tea downstairs could rise to my room. At the bottom of the stairs, I open a door on the left and enter the bathroom. The window is open; I close it immediately, shivering. The toilet seat is already down. Poised to undo my trousers and lower them, I dread the moment when my rear end is in the air, where the cold will strike my newly naked skin. But I dread even more the moment when I will place my naked rear end on the toilet seat, which I can only imagine is glacial. I must hurry and do all of this quickly to not give the cold time to rise through my nerves from my skin to my brain. I unbutton my pants, lower them just to my knees, and catch my underwear and lower it onto my pants. Folding my legs, I sit on the seat. It is warm, very warm, heated by electrical resistance integrated in the plastic, and this heat is communicated throughout my entire body, by conduction, to finally reheat me entirely, fully.

Philippe Rahm is a Swiss architect whose office, Philippe Rahm Architectes, is based in Paris. His work, which aspires to extend the domain of architecture to the physiological and meteorological planes, has been widely exhibited and nominated for numerous prizes. Recent projects include the 70-hectare Taichung Gateway Park, awarded by competition in 2011 and currently under construction. His book Météorologie des sentiments was published in 2015.