The following essay will appear in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, published this spring by the Avery Review and Lars Müller Publishers.

“Imagine we would live in a world with endless rainfall…” muses Anne van Galen, the designer of Warriors of Downpour City. The conceptual apparel collection, van Galen’s graduate project at Design Academy Eindhoven, responds to a fictional scenario in which postures and textiles have been adapted for rain and “fashion becomes naked, transparent and layered with thin diluted colors.”1 The molded plastic and silicone pieces serve at once to protect the body and accommodate its continuous movement through relentless fog and damp. Visual disclosure of the body through these gently protective garments, meanwhile, suggests an embrace of exposure to the elements. This project is an exemplary expression of a trend that can be traced from architecture to fashion design in which corporeal exposure to climate is mediated by more and more individualized and adaptable protective enclosures—a trend that should be seen as a reflection of the increasingly unstable condition of the climate itself.

At a historical moment in which the best available scientific predictions portend an almost unimaginably changed—and changing—future, explorations of hypothetical climates prepare us to register these changes perceptually and cognitively. Precisely because they invite us to inhabit fictional worlds, these kinds of projects interrupt our tacit habituation to an increasingly pervasive state of emergency and the unfolding of distant and slow disasters. Like the scenario exercises and disaster rehearsals conducted in the medical, energy, and security industries, aesthetic exercises in reimagining the conditions of everyday life prepare us to chart different paths into possible futures as well as reorganize our sense of the present.

This essay considers the role of speculative fashion design within the context of another such project of anticipatory aesthetics—a collective thought experiment called A Year Without a Winter. The project, organized by the authors of this essay, is being staged over the three-year period of 2015 to 2018 through research projects, events, and exhibitions at multiple locations around the world. At once a “futuring” exercise and a creative, historical reenactment of another global climate crisis, A Year Without a Winter deploys historical and literary narratives to reframe contemporary imaginaries of climate change. It brings together a broad coalition of artists, scientists, humanists, and policymakers to consider how humans and other species become acclimated to their environments and how, in turn, they alter built landscapes, cultural habits and artifacts, and forms of social organization in order to survive under unfamiliar or inhospitable conditions. Climate must be understood as a lived abstraction, one that discloses itself through new aesthetic logics and their critical analysis. In tracing a progression from architecture to apparel as sites of climatic mediation, it becomes clear that from the conceptual to commercial sectors, contemporary fashion is a sensitive indicator and rich site for the critical exposition of our increasingly turbulent seasons.

A Year Without a Winter

April 10, 2015, marks the two hundredth anniversary of the eruption of Mount Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa. This event set into motion a cascade of environmental, political, and cultural responses whose consequences are still felt today.2 The largest volcanic eruption in the last ten thousand years, Tambora caused vast destruction locally. It was forceful enough to inject ash and super-heated gases into the upper atmosphere, where stratospheric winds circulated them around the globe. By the following year sulfur dioxide and particulate matter blocked out sunlight and disturbed weather patterns worldwide. Much of the northern hemisphere was plunged into cold and darkness even as the Arctic warmed and tempted explorers north, while both intensified monsoons and drought afflicted the Indian subcontinent and East Asia. The “Year without a Summer,” as 1816 was remembered, was the beginning of a three-year climate crisis in which famines and epidemics led to political upheaval, migration, and reforms. It was also a year of profound literary and scientific inspiration. Efforts to understand the causes of this crisis later inspired new approaches to climate management—including today’s perhaps Promethean ambitions to cool our rapidly warming planet by intentionally putting sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, alongside other forms of solar radiation management meant to act as so many planetary parasols.3

The cultural legacy of this episode may be traced back to June of 1816, when a group of English literati vacationing on the banks of Lake Geneva found themselves cooped up by the incommodious weather. Lord Byron, John Polidori, Claire Clairmont, Mary Godwin, and her eventual husband Percy Shelley passed the time reading a collection of frightful German ghost stories and, eventually, set for themselves a friendly competition to write the best horror story. “The Dare,” as they called it, spawned two great “monsters of modernity:” Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus (1818) and John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), an inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).4 According to her own account, Shelley was inspired by the backdrop of dramatic thunderstorms, cold, and darkness and the general atmosphere of terror that these seasonal abnormalities occasioned. The novel, published in 1818 just as the cooling episode was beginning to subside, registered in compelling narrative form a cultural response to central scientific, technological, and political conditions of the day. Its power to shape our encounters with emerging science, technology, and environmental issues remains irresistible.

Two centuries ago, the world endured a year without a summer. We now confront the fearsome prospect of A Year Without a Winter—a future in which the elite luxury of escaping to sunny beaches for the holidays is rapidly being transfigured into a nightmare of global seasonal arrhythmia, bleached coral reefs, and sinking paradises. Many scholars, activists, and policymakers claim that climate change has failed to capture contemporary cultural imaginaries in a way that is sufficient to motivate adequate political, economic, and technological responses. Rob Nixon, for example, insists that there is an “urgent imaginative challenge currently facing both the humanities and the sciences, namely how writers and visual artists can embody environmental disasters in literary narratives and images, thereby making imaginatively perceptible and tangible to a broader public what scientists are establishing.”5 New visions and narratives are needed in order to harness the power of our scientific knowledge and intervene constructively in the course of the future.

What such stories and visions might be told or performed today, to capture the public imagination in the context of the all-too-plausible fiction of A Year Without a Winter? If the novel was a distinctive aesthetic form of the nineteenth century, what mediums and genres can best encapsulate an awareness of emerging climate crises? An answer just might be found in an outfit.

Climate as a Lived Abstraction

In a political atmosphere of carefully policed climate literacy, we are often reminded that no single event—storm, flood, glacier calving—can be directly attributed to climate change. This is not due to any failure of climate science but rather to the nature of climate itself, as indicated by the old adage “climate is what you expect; weather is what you get.” Another suggestive anecdote offered is by climate scientists: “If I look at what you're wearing today, I would learn something about the weather. If I were to look inside your closet, I would learn something about the climate you live in.”6 The closet is an archive of one’s climatic expectations and aspirations. What might one learn about weather and climate by discovering Jacqueline Bradley’s Boat Dress in someone’s wardrobe? The inflatable dress, part of an installation titled “The Outdoors Type,” includes a variety of playfully functional picnic accoutrements. The resourceful feminine archetype evoked here is well prepared to explore and cope gracefully with her environs. She is also prepared for them to change—perhaps quite suddenly.

In order to understand why apparel offers an evocative aesthetic modality through which to comprehend today’s environmental crisis, we must consider more precisely what climate means in contemporary discourse. Climate, along with atmosphere, air, and a constellation of related meteorological concepts, often refers to an ambient background condition perpetually at the edge of perceptual awareness. Like tools that we rely on without noticing their particular properties, climate calls attention to itself phenomenologically only when it misbehaves or manifests itself in particularly dramatic ways—usually in the form of bad weather. If “there will be weather today,” then you will probably need to dress for it. As the object of atmospheric science, “climate” denotes the average weather of a particular locale, from a room to the whole world, over a period of time ranging from days to seasons, human lifetimes to millennia. More precisely, climate is a statistical description of the mean and range of variation of temperature, precipitation, wind, barometric pressures, and other factors in a defined spatial and temporal domain—thirty years, by the standards of the World Meteorological Organization. The concept of global climate—a notion that emerged only in the last century—must be understood as a mathematical and conceptual abstraction.7

A historical answer to the question what is climate? offers a very different picture, however, one that places geography and human interests in the foreground. This perspective recalls our attention to the lived experience of climate and the material artifacts we build to control that experience. In their study of the ancient concept of klima, James Fleming and Vladimir Jankovic argue that climate has predominantly been conceived of as an agency affecting human bodies and affairs. Climate refers to “all the changes in the atmosphere which sensibly affect our organs” and influence “the feelings and mental conditions of men,” in the words of Alexander von Humboldt.8 While atmospheric science treats climate as a set of conditions to be indexed, averaged, and modeled, the language of agency pervades discourses of climate change and its effects on economies, political conflict, food and water security, and, not least importantly, the weather. Considered as an abstraction over space and time, climate lies outside the domain of direct sensory experience. What does it mean, then, to be subject to its agencies, to those temporary states of the atmosphere that the climate models tell us are becoming increasingly turbulent and extreme? How do we live in and with the abstraction of climate, and how do we express our comprehension through quotidian practices, objects, attitudes, and desires?

The Explication of Climate

Attending to climate—to long-term trends and tendencies in how the atmosphere behaves and changes over time—may be done by considering how we modulate its effects on our habitus. Architecture is one obvious site to consider, for example, in its many forms of climate control—heating, cooling, insulation, air circulation, etc. Peter Sloterdijk, for instance, has given us ample conceptual apparatus for conceiving architecture in atmospheric terms. We live, he argues, within so many bubbles within bubbles, which contain and regulate not only airflow but the forms of life that thrive therein. As he shows in Terror from the Air, the twentieth century witnessed a proliferation of social and mechanical technologies for manipulating the atmosphere, from air conditioning to flight to chemical warfare. These technologies interrupted our tacit reliance on air for the basic most purposes of breathing, even as its many new affordances were celebrated in the domains of transportation and communication. Sloterdijk highlights how moments of atmospheric breakdown bring the ambient conditions of life more explicitly into the foreground, a process he calls the explication of the environment. Such practices of awareness lie at the basis of any possible experience of climate change.

If we scale this analysis down and individualize it, we can trace a similar mediation of atmosphere through the convergence of architecture with clothing. Sloterdijk recounts a particularly ironic story of Salvador Dalí in which the artist very nearly dies of suffocation when he gets up to deliver a lecture on surrealism and the unconscious dressed in a diver’s helmet. Though the helmet was designed to enable breathing underwater, Dalí neglected to connect the helmet to an air supply, and his wild gesticulations and distraught facial expressions were construed by the audience as an ingenious performance. For Sloterdijk, “The artist’s choosing to wear a deep-sea diver suit with an artificial air supply for his performance as the ‘Ambassador from the depths’ unerringly ties him to the unfolding of atmospherical consciousness, which, as I have attempted to show, is central to the self-explication of culture in the twentieth century.”9 Though understated by Sloterdijk, this story yields a further insight by pointing our attention to the role of clothing in the explication of a more specifically climatic consciousness.

In an atmosphere of looming environmental crisis, it might seem callous or trite to focus on fashion as such a site of climatic imaginaries. Yet to do so is not to trivialize the matter. On the contrary, whereas the prospect of catastrophic climate change remains on the verge of the unthinkable, clothing remains a domain of daily acknowledgment of and adjustment to our climatic horizons. Like architecture, fashion constitutes a mediating point between the imagination of the local and embodied habituation. We change our clothes more frequently than we change our homes and built environs, however. To continue along Sloterdijk’s line of thought, our homes, offices, and cities can be construed as so many spheres—bubbles within and adjacent to other bubbles. In microcosm, the clothing that we outfit ourselves in may accordingly be thought of as more intimate bubbles blown daily from the options within our wardrobes.

A pair of projects by Archigram—the 1964 Cushicle and the 1967 Suitaloon—offer a key conceptual transition point in this genealogy of speculative fashion design as a site to explicate climate and thus richly evoke climate adaptation. Inspired by the accoutrements of space travel, these prototypes of “clothing for living in” were designed as inflatable mobile homes, offices, or leisure spaces for one or more occupants. They were also exercises in minimalism, designed to deliver the most basic requirements of shelter and comfort. A point of contrast that marks the boundary between architecture and apparel, these examples of wearable architecture fully enclose their users. In a very minimal sense, one may be considered to be “indoors” when ensconced in such a space and, as such, in a space where climate can be regulated.

Designed well in advance of widespread concerns about climate change, the Suitaloon nonetheless gestures toward a question that will be reiterated implicitly in later such garments: how does apparel reflect our needs, desires, and expectations of the climates we inhabit? In the work of Archigram, these needs and desires retain an element of humorous utopianism: “If it wasn’t for my Suitaloon I would have to buy a house,” wrote designer Michael Webb.10

Lucy Orta’s 1994 collection Refuge Wear similarly includes a range of wearable shelters, yet these are designed for conditions of social and environmental precarity, for homelessness. Hooded tents and body suits enable sleeping on sidewalks in conditions of rain or cold, in hyper-mobile form. Between individualized refugee tents and protective clothing, these garments do not purport to substitute for a comfortable living environment. Rather, they offer the wearer minimal protection in the context of an inhospitable environment—an environment in which political and economic conditions expose bodies to the ravages of an unstable climate and vulnerability to risk is unevenly borne. Orta’s Refuge Wear, like the Boat Dress and the gear worn by van Galen’s Warriors of Downpour City, reflects a condition of immersion in and direct exposure to hypothetical climates. And like Dali’s deep-sea diving suit, they are legible as material expressions of the long-term trends, cyclical behaviors, or unpredictability of the climates that they enable their wearers to endure—and enjoy.

Unseasonal Fashion

As fast-moving consumer goods with a profit structure based on high turnaround, clothing is a highly sensitive indicator—and a driver—of how hopes and fears are invested in consumer cultural imaginaries of climate and environmental disaster. A recent study in fashion marketing notes that “fashion retailers and brands can often be caught out by unseasonable weather. The problems seem to be most acute in the autumn as later warm weather means that consumers are reluctant to begin purchasing heavier clothing.”11 The realization of the fictional scenario of A Year Without a Winter could occasion major economic losses for certain sectors of the fashion industry and yet be a boon to others. An exemplary site of aspirational consumption, the suggestively named cruise collection appears in late winter with light fabrics and luscious prints to stoke desire for warmer weather and holidays, offering vicarious pleasure even to the non-cruising set. Fashion seasons, industry analysts recognize, will be affected by climate change in form and content, for “although this may be a merchandising issue, it is likely to have an impact on product design and ranging for autumn collections in the future.”12

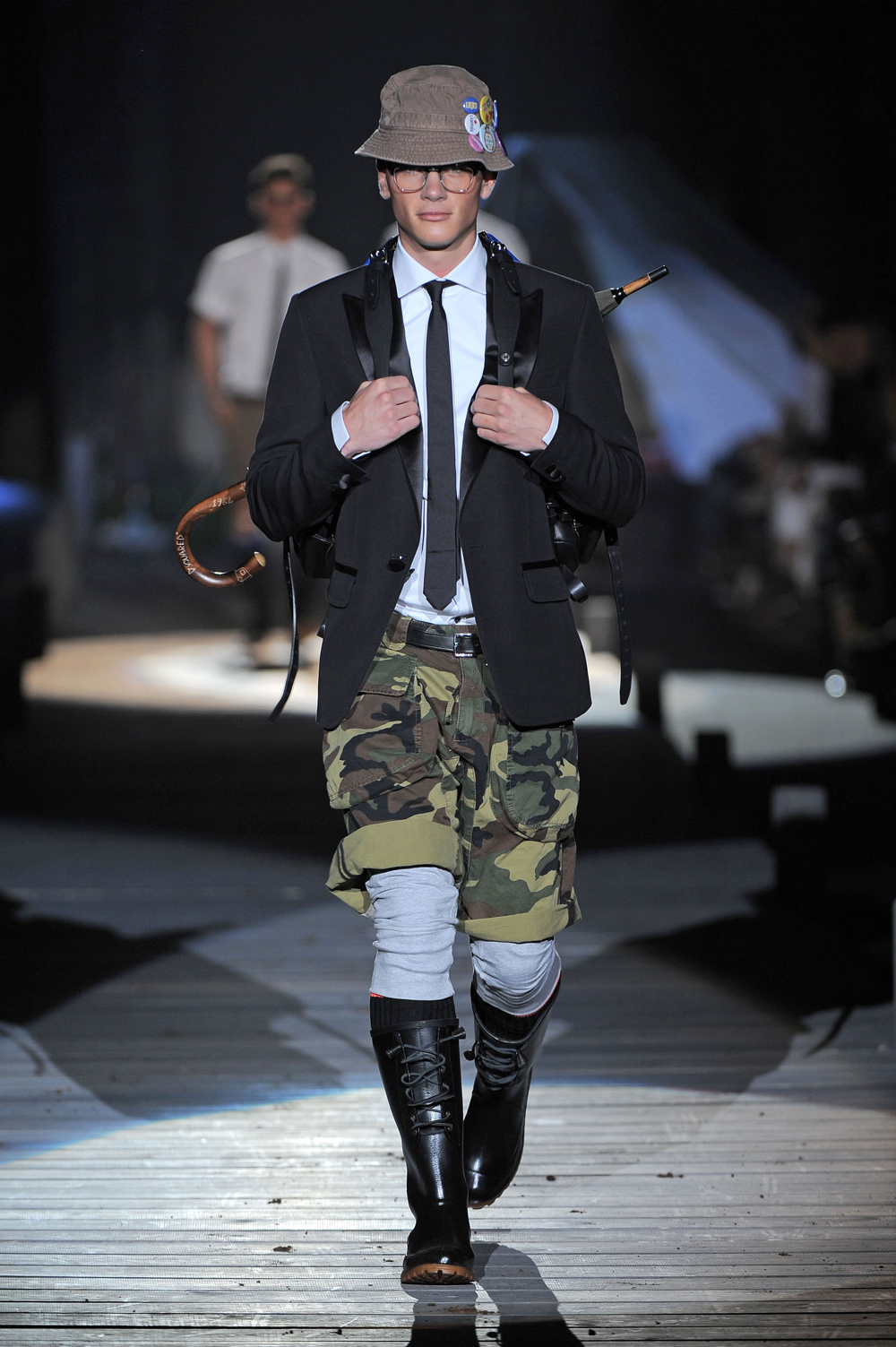

The effects of seasonal disruption on fashion design can already be observed on the runways, in art fashion, and even in the streets. A notable “look” seen in the Summer 2010 show of the Canadian designers Dean and Dan Caten, aka Dsquared2, is a veritable montage of survivalist tropes. The model sports an outdoorsy fisherman’s hat and rain boots, connoting leisurely self-sufficiency in the wilderness, and camouflage shorts, crossing military and hunting motifs. In his stylish gear pack he carries an umbrella, prepared in case of inclement weather. The whole ensemble is immaculately topped off with a black tie and tuxedo jacket that cannot but imply the survival of the 1 percent—a fine outfit for work and play in the age of disaster capitalism.

Gas masks and other accessories for apocalypse are already familiar on the runways through the work of Alexander McQueen and Rei Kawakubo, for example. High fashion serves at once as a site of critique and a space in which disaster chic normalizes and articulates new possibilities for pleasure within a changing world. A sociological perspective on dress suggests that “body supplements,” which may include any article of clothing, “act as alterants of body processes as they serve simultaneously as microphysical environment and as interface between body and the macrophysical environment.”13 Particularly notable in these high-fashion examples is that the means of mediating between body and climate are often detachable, suggesting both that adaptation may take place quickly and that the wearer enjoys flexibility in the environments that she frequents. Umbrellas are detachable appendages, liable to being forgotten, lost, or stolen, even flittering off of their own accord, as though they live lives of their own. This makes the umbrella an unreliable mediator between the body and its social and meteorological milieu.14 In contrast, protective weather gear that more securely affixes to the body comes closer to architectural stability, on the one hand, and to a second skin, on the other. On both counts, the reliability of a piece of apparel as an environmental mediator is a measure of the relative uncertainty of the wearer and the climate itself.

Fashion always represents a negotiation of taste and necessity, where the degree to which one’s dress reflects taste is a matter of privilege, opportunity, and proclivity for self-fashioning. From the rise of camouflage in the 1960s to the recent proliferation of prints featuring disturbed landscapes and a popular fetish for high-tech outdoor gear, fashion history offers an archive of rapidly shifting attention to social and environmental milieus. The act of putting on clothes each day represents a fine-grain mode of responsiveness to shifting standards of thermal comfort, a register of planned passage through indoor and outdoor climates, and a reflection of our horizons of expectation about what kind of weather the day and season may bring.

Recent fashion trends resonate with a cultural unconscious of a looming environmental disaster. Clothing, like buildings, reflects an understanding of the weather and climate of their users. Because they can be changed much more frequently, wearable interfaces with the environment reflect both the conditions common in that environment and how predictably and frequently change occurs therein. Fashion is uniquely positioned to function as a cultural register of climate change precisely because it captures and is governed by trends. Comprehending climate change means recognizing long-term trends in and through short-term variability and cyclical repetition, patterns of change that are part and parcel of fashion design. Moreover, from production to distribution, fashion is global.

This essay is supported in part by the US National Science Foundation cooperative agreement no. 0937591. Any findings, conclusions, or opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent NSF. The authors are also indebted to Jacob Lillemose, curator of X and Beyond and postdoctoral fellow at the Copenhagen Centre for Disaster Research, for extensive discussion of the role of fashion in the imagination of disaster.

-

“Anne van Galen Designs Accessories for a ‘World with Endless Rainfall,’” Dezeen, November 2, 2014, link. ↩

-

Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Tambora: The Eruption that Changed the World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Jack Stilgoe, Matthew Watson, and Kirsty Kuo, “Public Engagement with Biotechnologies Offers Lessons for the Governance of Geoengineering Research and Beyond,” PLoS Biol, vol. 11, no. 11 (November 2013). ↩

-

Kim Hammond, “Monsters of Modernity: Frankenstein and Modern Environmentalism,” Cultural Geographies, vol. 11, no. 2 (April 2004): 181–98. ↩

-

This description is drawn from the abstract of a talk given by Rob Nixon titled “The Anthropocene: Slow Violence and Environmental Time,” link. ↩

-

As related in private conversations with climate scientists. ↩

-

For further discussion of the emergence of the “global” concept of climate, see Paul N. Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013). ↩

-

James R. Fleming and Vladimir Jankovic, “Revisiting Klima,” OSIRIS 26 (2011): 1–16. ↩

-

Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009), 77. ↩

-

Tony Hines and Margaret Bruce, Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues (London: Routledge, 2007), 172. ↩

-

Hines and Bruce, Fashion Marketing, 172. ↩

-

Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins and Joanne B. Eicher, “Dress and Identity,” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, vol. 10, no. 4 (June 1992): 4. ↩

-

Maria Damkjær, “Awkward Appendages: Comic Umbrellas in Nineteenth-Century Print Culture” (article under review; cited with permission of the author). ↩

Dehlia Hannah is a curator and a philosopher of science and aesthetic theory. She is an assistant research professor jointly appointed in the School of Arts, Media, and Engineering and the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at Arizona State University and a guest researcher at Copenhagen University. Her current book project, titled Performative Experiments, explores the philosophical implications of artworks that take the form of scientific experiments. She has written and curated art exhibitions about climate change, the Anthropocene, and new media. With Cynthia Selin, she leads A Year Without a Winter (2015–2018).

Cynthia Selin is an interdisciplinary scholar focused on the future. She is an assistant professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University and an associate fellow at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School. She investigates and invents methodologies for clarifying uncertainty and explores more theoretical questions about anticipation in society.