Understanding such spaces of “unbelonging” and the conditions of personal and national security with which they are entangled is essential to grasping the present moment … Where might a critical imaging of a refugee’s future commence? To start at the margins—in exile—is to visualize and occupy the insecurities of living.

—Curator’s statement, “Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter,” Museum of Modern Art

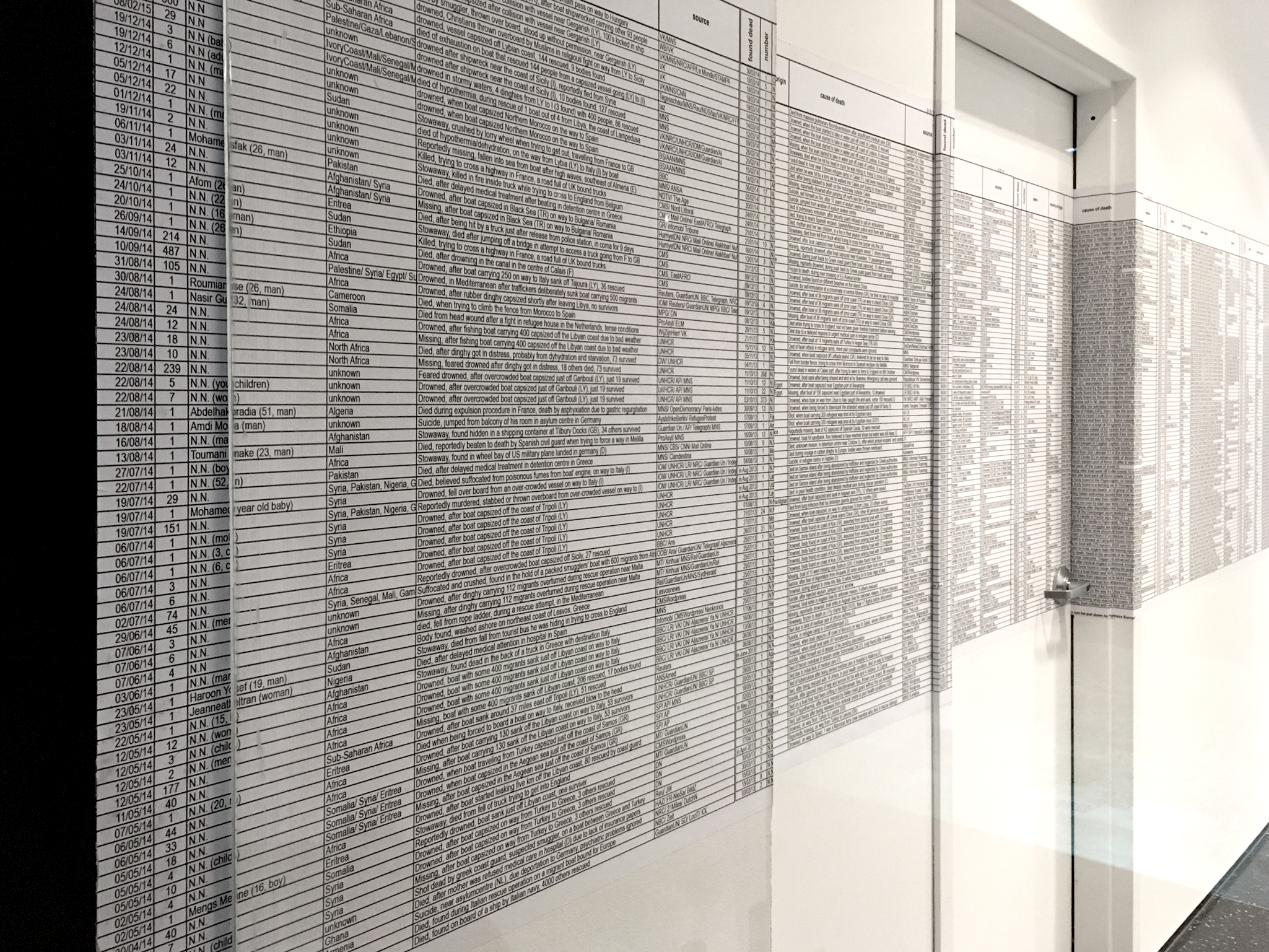

The exhibition space is very small, its entrance tucked between the escalators and the espresso stand on the crowded mezzanine level of the Museum of Modern Art: within the bustle and yet easy to miss. Crossing the threshold takes the visitor into a room filled with the sound of an artwork whose design, by no curatorial accident, fulfilled the expedient role of delimiting an acoustic enclosure and producing a proprioceptive exit from the thoroughfare outside. The audio recalls the steady, muffled pulsation of a machine underwater, and with the photographs of marine-borne migrants and escape vessels, proposes a space and sense of the maritime. A second entrance, from a neighboring gallery, is papered with the names of people who perished in flight, including many who, quite literally, fell into the sea.

This sensory habitus may not distract the viewer who seeks or stumbles upon this exhibition from what, on first blush, may be an unsettling, even revolting, juxtaposition of the perils of forced migration with the cafeteria and bathrooms of the second floor—what may appear as an inappropriate repurposing of the lived experience of the “unbelonging” many, whose lives happen far from the art consumption in the emporium at Fifty-Third Street. Moreover, if the majority of these consumers arrive with nonspecialist purposes—meditations on Water Lilies rather than Architecture and Design—then what is this intervention, indeed, other than an apparatus for privileged shame? The response to that is complicated.

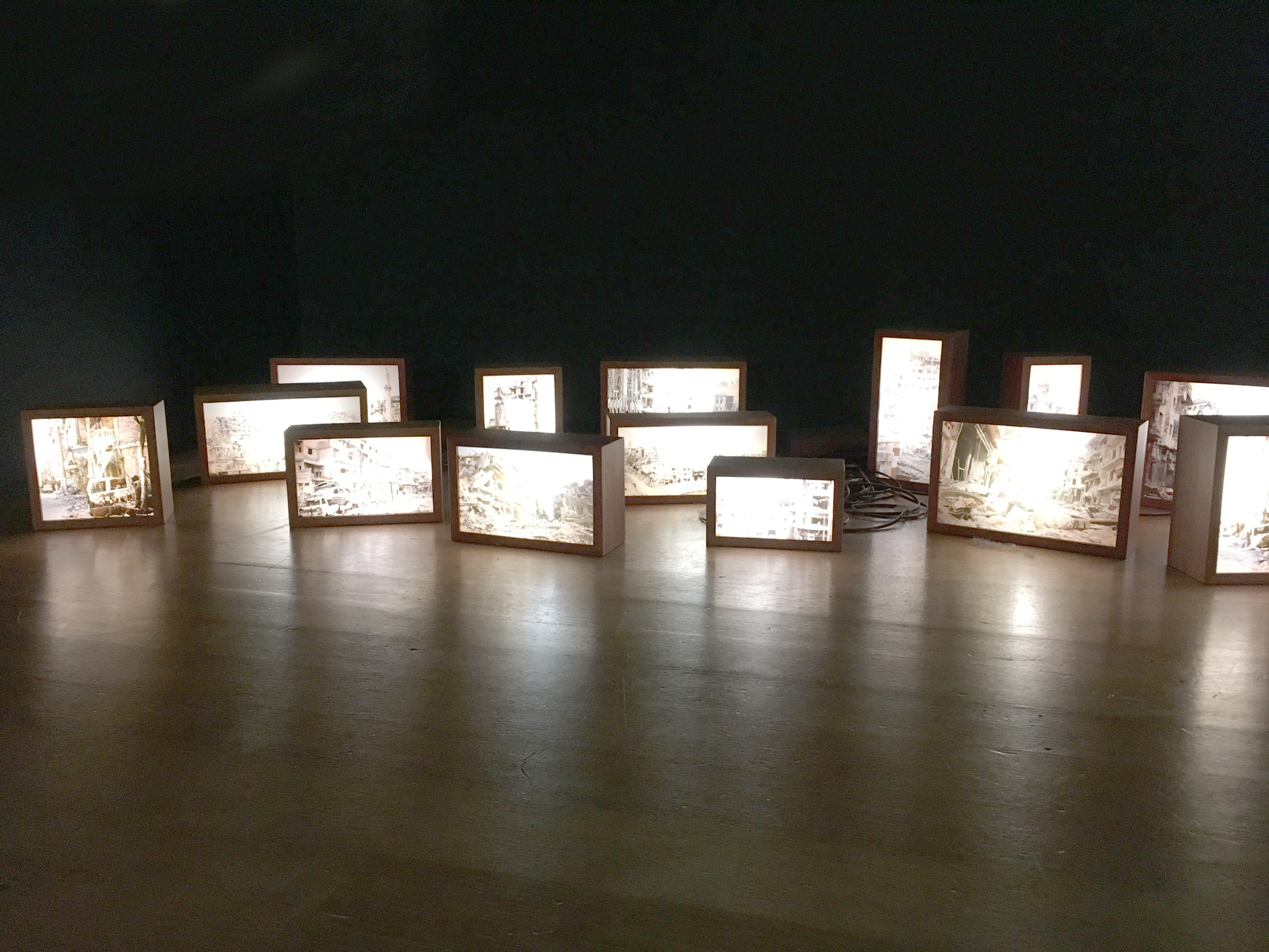

Let us return to the exhibition space, whose relative smallness begins to dismantle the problem. As the viewer’s orientation shifts to the objects and images, away from an expansive mode of comprehending display and toward an intimate practice of registering documentary matter, a strange set of bedfellows emerges. To be sure, the artifacts selected to commence “a critical imaging of a refugee’s future” include the inevitable photographs of architect-designed shelters and camps composed of relentless grids. However, their arrangement situates them to perform different work than might be expected. If these are the instruments for tracing displacement and shelter, they do this through a set of frequent imbrications—the artwork with the design object with the utilitarian device, the artist’s commission with the refugee’s, the operative with the poetic—from UNICEF’s aspirational “School-in-a-Box” for eighty students, made of protractors, notebooks, lesson plans, and other teaching tools in a metal suitcase, to the hand-fabricated mahogany lightboxes framing found photos of demolished streets and buildings in Tiffany Chung’s “finding one’s shadow in ruins and rubble.” The Museum did not acquire any of the works; they are on temporary display in the exhibition.1 This, along with a series of other conditions—the curatorial juxtapositions, the interruption reinforced by the adjacency to and separation from the demands of the immediate exterior, the simultaneous view of all the objects afforded by the size of the room, and the occasional absence of textual narrative accompanying objects on display—script a special institutional enclosure within which to view, consume, and interpret forced migration.

To be more precise, there is a way in which this temporary collection encourages a reading of the displayed objects as forced migration’s “artifacts,” in the archaeological sense—items of cultural or historical interest, made by human beings through investigative procedures and careful preparations. It limns these artifacts not as illustrations but as documents of forced migration, which then permit not only interpretive study, but analysis with a more scientific orientation. Through the materiality and sensibility of the objects and images, the real events and people they represent, and the museological context and adjacencies discussed, the exhibition performs an ekphrasis of the condition of forced migration, vocalizing circumstances largely muted by institutions, including the institution within which it sits.

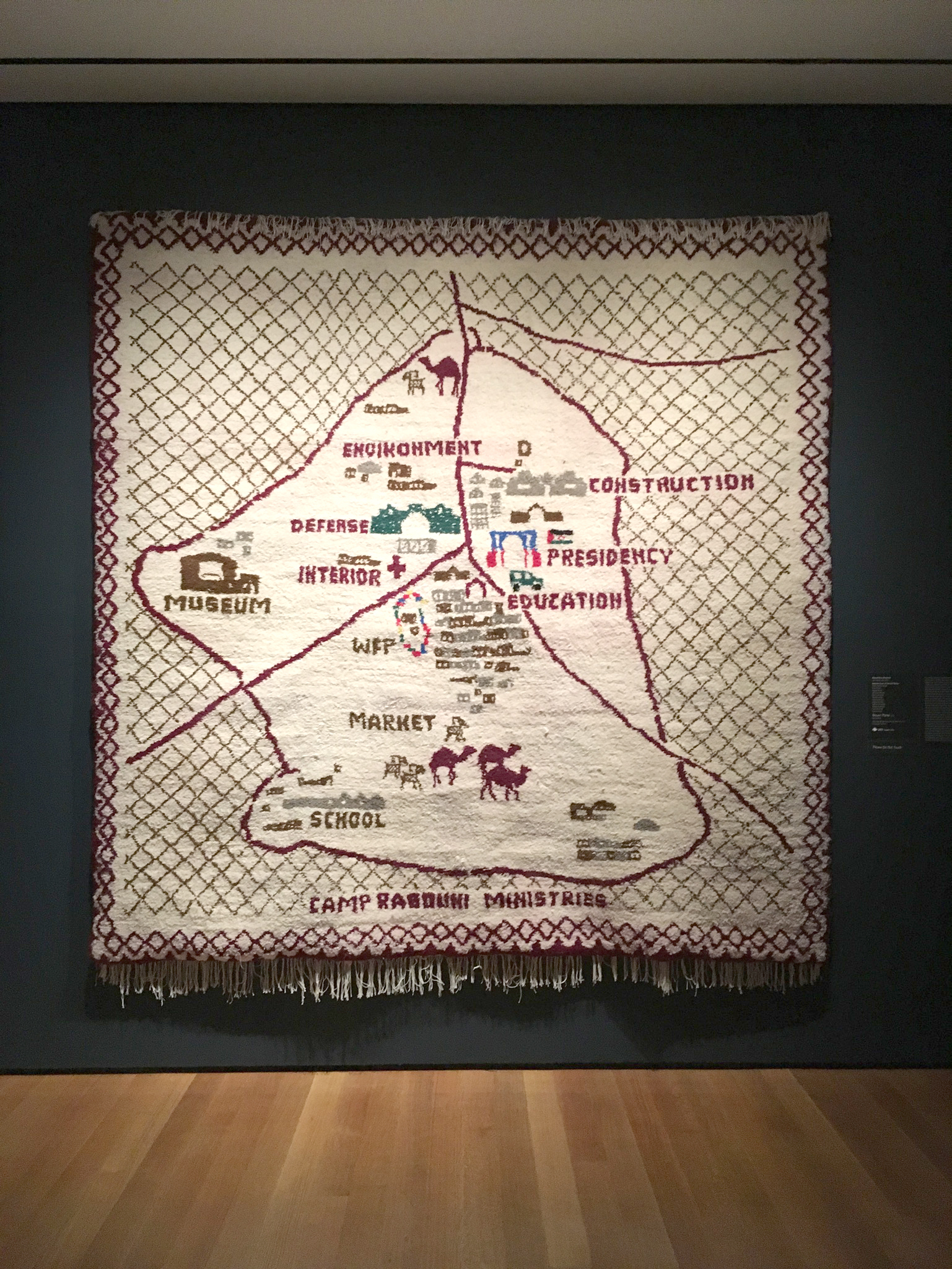

For example, the artist credit for the woolen administrative map in “Woven Panel” lists Manuel Herz Architects above the National Union of Sahrawi Women—Fatma Mehdi Hassan, Tchla Pachri, Argaya Achaij, Mahyuba Ahmatu, Fatma Ambarak, Atfarah Asalak, Mahyuba Alaal, Angaya Ahmed, Mariam Mohamed, Ajrebicha Ahmed, Fatimatu Abdy, Asalma Achej—and without precise differentiation of the labor of each in the curatorial statement, one is left to imagine the practices of the collaboration, exactly “how stateless individuals, in particular women, continue to actively contribute to cultural production,” as the placard states, and through the institutions of what territory—Rabouni, the Saharan Arab Democratic Republic, Algeria, the Western Sahara, Switzerland, the world? That said, one can imagine a curatorial practice in which the latter artist, let alone the names bracketed under the unexplicated National Union of Sahrawi Women, might not be cited at all; indeed, the associated online database does not include the expanded list of names. This citation allows us to ask questions about these twelve women as well as the unnamed architects who provide the plural to Manuel Herz Architects—the two sets of hands at work in the intercontinental collaboration directly engaged in authorship.

The institutional coherences and fissures that this example reflects are also to be found in the museographical setting of such artifacts within and among the wider geography of the Museum’s spaces and architectures—onsite and off, permanent and temporary, directly administered and indirectly managed. It might be cautiously noted that this unevenness, the adjacency of formalities and informalities, mirrors the landscapes associated with colonial institutional archives. If read in this context, in spite of their merely temporary gathering in this room, these artifacts offer themselves as sites of evidentiary meaning, perhaps first and foremost, sometimes even quite literally as forms of evidence. Ironically, this occurs within a framework whose colonial resonances modern art the world over ostensibly sought to resist.

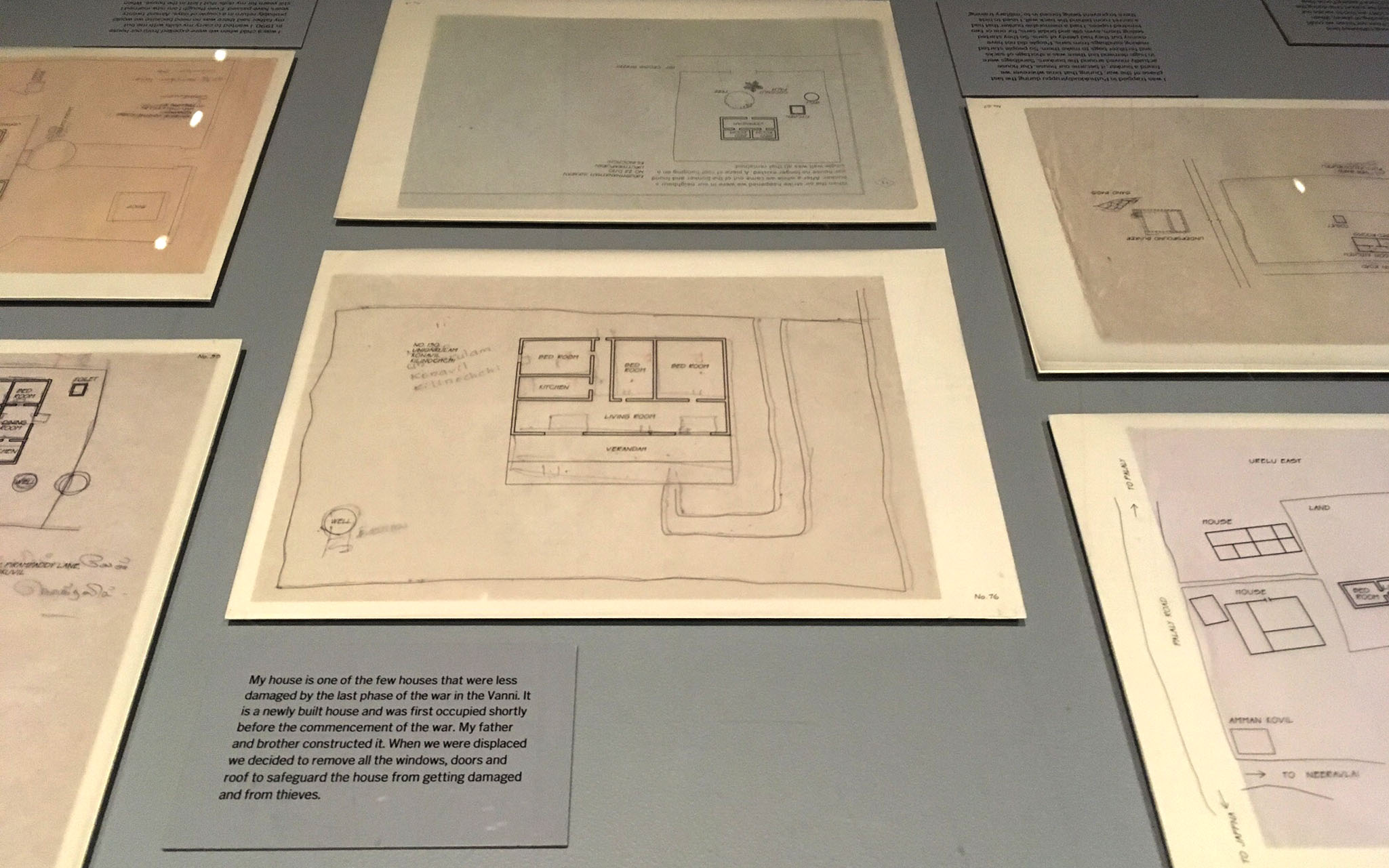

This fundamental aspect of the awkward labor performed by this temporary collection of artifacts, at once designed and made, institutional and informal, authored and found, pushes against the curator’s provocation “to visualize and occupy the insecurities of living.” Such an exercise in seeing and inhabiting suggests that the primary discursive gesture of the exhibition would be its evocation of the present moment. Alternatively, these objects and images might be understood very differently: as invoking, rather than evoking. In the 1994 Médecins Sans Frontières “Middle Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) measuring device” used to calibrate the care of human bodies with morbidity standards; the 2014 copper prints by architectural studio Rael San Fratello caricaturing the boundary between the United States and Mexico in “Xylophone Wall,” “Horse Racing Wall,” “Cactus Wall,” and “Teeter-Totter Wall”; or the house floor plans reconstructed by the Jaffna displaced, with artist Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan in “The Incomplete Thombu” in 2011—to name but three examples that range, like the others, from instrument to fantasy to chronicle—the precision of each object conjures forth some historical place and time, a specific case of emergency whether closed or open. That the first two artifacts lack accompanying contextual description, and the third uses documentary methods, reinforces a reading of these as primary sources, forcing the visitor to make a direct epistemic transaction. To borrow from the recently departed John Berger, “When we ‘see’ a landscape, we situate ourselves in it. If we ‘saw’ the art of the past, we would situate ourselves in history.”2 Applying this thinking to the problem at hand, “to visualize and occupy” is to engage in seeing what a landscape or art invokes: the past, or a historical present, following Berger, which might otherwise be obscured by “a privileged minority … striving to invent a history.”3

The question of artifacts acting somehow as bearers of history has been well tussled over by art historians and is not quite representative of the stakes here. The complicated element of this exhibition is the problem of specific artifacts, which record, imagine, or intervene into a precise historical condition of forced migration in the present and in invoked pasts. In particular, the history that they explicate is one drawn from institutional structures (not excluding that of the Museum of Modern Art), which engaged broader political landscapes that reproduce the formations and categories of colonial and occupying powers. How can we speak of UNITED for Intercultural Action’s “List of Deaths” of refugees who perished in the attempt to reach safety, without naturalizing modern territorial histories that produced borders in the Maghreb, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe? In an exhibition on displacement, how should the visitor understand the lack of attention to the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions cultural protest, engaged widely by artists as part of a movement pertaining to some of the longest-standing political communities of the displaced? Are we to examine Better Shelter’s “Emergency Temporary Shelter” flat-pack unit deployed in the center of the room—according to its website “developed together with the UNHCR and the IKEA Foundation”—and look away from the UNHCR’s acceptance of a massive donation and offer to work with the IKEA Foundation the week after reports tied IKEA’s founder to the Swedish Nazi party?4 And yet the preservation of artifacts (historical and aesthetic) depends quite crucially on the structure of state and localized institutions, within which a great deal of colonial violence has been interred. Conversely, and significantly, embedded in such structure is an institutional architecture for the framing and writing of history.

That architecture, it is important to note, has fractures wide enough for scholars of the world of art to inhabit. For instance, the figure of the refugee has not been alien to the Museum of Modern Art. Notably, during World War II, Margaret Scolari Barr and Alfred H. Barr Jr. (the latter the Museum’s founding director, and the former an art historian and his spouse), worked closely with the Emergency Rescue Committee, an institutional predecessor to the International Rescue Committee. They aided approximately two thousand artists, art historians, art dealers, and others who worked in science, literature, and music, in escaping Vichy France and establishing visa status in the United States, with Peggy Guggenheim and others in the Museum’s sphere joining suit.5 Given that, does it not serve a greater logic that we approach this exhibition with a view to historiography, seeing it as animating a path in the museum’s historical trajectory? The curatorial statement does not address this institutional history of real intervention to protect heritage and human life together (the inseparability of the two having become a pearl in the contemporary international rhetoric, for instance, as UNESCO and the Louvre make the case for a cultural contribution to the “war on terror”).6 However, the attentive selection of artifacts and role of the organizers in the professional landscape suggest a sensitivity to this history and broader agendas in the world of art collection, as well as a familiarity with narratives of forced migration; what perhaps we do not see are the various cultural and other politics that may have emerged as a scholar of the architecture of African colonization mounted a maiden exhibition in this setting.7 If this suggestion of multiple complexities, historical and historiographical, resides even at the surface, might not an institutional ethnography as such expose other likely fault lines?

The conundrum here is that the institutional silo and collecting practices in the world’s first major curatorial department dedicated to architecture and design have not enabled canonical stability for the objects in this exhibition, and, in turn, the institutional discursive space reinforces a colonial apparatus of knowledge production, but in spite of these problems, the exhibition constitutes a vital archive.8 Its figuration of displacement is structural—itself liminally housed, within a partitioned institution; its imagery adhering to no fixed grammar; accompanying no institutionalization of works; even including artifacts that are necessarily utilitarian, often measuring or facilitating bodily function. The “bare life” of objects, as it were. Notwithstanding, however temporary an archive, it may be one of the only sorts we have for an architectural history of forced migration.

The assemblage occasions historical recuperation and thought. “The Incomplete Thombu” imagines the spatial violence associated with Sri Lanka’s 1983–2009 civil war, during which “destruction of living environments, the creation of high security zones and detention camps, forced migrations, ethnic expulsions, civilian casualties, and contamination of conflict-affected areas with landmines and unexploded ordinance … drastically altered the earlier social fabric.”9 Moreover, the work presents this history by posing “records of properties and lands belonging to Tamil-speaking citizens prior to single or multiple displacement from their homes,” under a title evolving linguistically from the Greek tomos through the Latin tome, and finding its way to Sri Lanka as thombu through Portuguese and then Dutch trade.10 According to T. Shanaathanan, “Winslow’s Tamil dictionary, also called the Maanippaay dictionary, defines Thombu (Thoampu) as a public register of lands.”11 This logic at once extends the definition of the archival document and the form and space of its institutionalization.

The work of Brendan Bannon, “Ifo-2, Dadaab Refugee Camp,” represents a reversal. Through its scale and framing, the journalistic photograph becomes the work of art. In that discursive reorientation lies a blueprint for an architectural history of Dadaab, a site that has represented a historical paradigm shift in emergency urbanism and the architecture of humanitarianism.12 It depicts the organization of settlement in the dusty red field of Kenya’s border with Somalia not with mere technocratic relentlessness but as figuring and constituting a specific horizon. “Woven Chronicle,” Reena Saini Kallat’s “quasi-cartographic drawing” of the conventional map of the world recalls “channels of transmission,” and technologies of “barbed wire or different kinds of fencing” with electrical wires unraveled from purported balls of yarn on the floor.13

This vocabulary for forced migration, from its most mappable to its most handspun, expands to encompass the room in the aural milieu discussed in the beginning of this essay—made of “high-voltage electric current sounds drowned within deep-sea ambient sounds, slow electric pulses, the hum of engaged tones from telecommunications, mechanical-sounding drone, factory sirens, and ship horns intermingled with migratory bird sounds.”14 Again, with Berger, “images are more precise and richer than literature. To say this is not to deny the expressive or imaginative quality of art, treating it as mere documentary evidence; the more imaginative the work, the more profoundly it allows us to share the artist’s experience of the visible.”15 If we allow the artist here to be the international agency, the nongovernmental medical organization, the practicing architect, and the refugee, then indeed Berger’s point about seeing implicates us to register these artifacts as visions of forced migration’s past and historical present. The histories that may accordingly be written need not be purely for the colonial power but also for the subject.

Some may contest this argument, saying that the ethnographic view of this careful gathering and installation of artifacts in the museum is too generous; that interpreting the discursive silo around objects as an archival form apologizes for colonial practice; that housing such an exhibition in this institution alone situates it in the black and white rather than in the gray. This may be. But the terms of this institutional black and white may also shift, thinking especially on its street address four city blocks away from the penthouse at 725 Fifth Avenue, which, at the time of this writing, is being reconfigured for altogether new forms of power. In this socio-spatial zone, the interstices (perhaps assuming the form of exhibition; perhaps something else) may take on very different meaning, and the material arrows to the past embedded inadvertently within institutions may hold narratives of threats and violence that we may never otherwise know.

-

This was raised by the exhibition curator Sean Anderson, in a New York University in-class discussion in the author’s course “Africa / City,” November 2, 2016, and reflects the context up to that date. According to the object labels, the exhibition includes materials gifted to the Museum of Modern Art, such as the “Emergency Temporary Shelter” by Better Shelter. ↩

-

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: Penguin, 1972), 11. ↩

-

Berger, Ways of Seeing, 11. ↩

-

See bettershelter.org; “IKEA Foundation Gives UNHCR US $62 million for Somali Refugees in Kenya,” UNHCR news, August 30, 2011, link; “Ikea Founder Ingvar Kamprad Involved in New Nazi Claims,” Associated Press, the Guardian, August 25, 2011, link. ↩

-

Christina Eliopoulos, “In Search of MoMA’s ‘Lost’ History: Uncovering Efforts to Rescue Artists and Their Patrons,” Inside/Out: A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog, June 22, 2016. See also United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ed., Assignment Rescue: The Story of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee (Washington, DC: USHMM, 1993). ↩

-

In response to Islamic State attacks on Palmyra and the brutal killing of antiquities scholar Khaled al-Asaad, officials of the Louvre under direction of the French state articulated a plan for the institution to provide “asylum” to endangered artworks and monuments, spurring a variety of reactions to the linking of heritage with human life in emergency. Kareem Shaheen and Ian Black, “Beheaded Syrian Scholar Refused to Lead ISIS to Hidden Palmyra Antiquities,” the Guardian, August 19, 2015, link. Jonathan Jones, “Asylum for Artefacts: Paris’s Plan to Protect Cultural Treasures from Terrorists,” the Guardian, November 20, 2015, link; “International Push Aims to Protect Endangered Heritage,” Middle East Eye, December 2, 2016, link; Maya Vidon, “France Spurns War-Zone Refugees but Welcomes Their Art Treasures,” USA Today, December 18, 2016, link. ↩

-

Sean Anderson, Modern Architecture and Its Representation in Colonial Eritrea: An In-visible Colony, 1890–1941 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015). For information on the curatorial team, see link. ↩

-

For more on the workings of the department, see Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, “Finding Chance: Reflections from the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art. Interview with former Chief Curator Barry Bergdoll,” the Singapore Architect, special issue on “Curating Architecture” (2016), 131–142. ↩

-

T. Shanaathanan, The Incomplete Thombu (London: Raking Leaves, 2011), back cover. ↩

-

Shanaathanan, The Incomplete Thombu, front cover. ↩

-

Shanaathanan, The Incomplete Thombu, front cover. ↩

-

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, “Just Add Water? Architecture and Humanitarianism, 1991–2011” (PhD dissertation, New York University Institute of Fine Arts, 2014). ↩

-

Kallat, “Woven Chronicle.” ↩

-

Berger, Ways of Seeing, 10. ↩

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi is Assistant Professor and Faculty Fellow at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University. She is the co-editor of the volume Spatial Violence (Routledge, 2016). Her scholarship and teaching focus on spatial politics, urbanism, and modernist culture and discourses, with historical and ethnographic research based substantively in East Africa and South Asia.