I

We would like to tell you a story, one that is simultaneously abstract and real, metaphor and metal: a personal-plastic-performance.1 It begins with a man on a stroll through the Paris Zoo in 1878. The man: a portly goateed French obstetrician by the name of Stéphane Tarnier. On that morning, Tarnier felt particularly saddled with the burden of an impoverished state. The Franco-Prussian War left France desperate for future soldiers—a desperation that seeped into Tarnier so deeply that he found himself searching for life in the most mundane of objects. As he walked with the weight of war and famine on his shoulders, past the bear pit and the monkey house, he came across a warming chamber for rearing chicks in the Great Aviary. In this couveuse, or “brooding hen,” Tarnier saw a life-saving machine. Too many good babies, or future productive members of society, had died under his watch, and “like a good Frenchman, he abhorred waste.”2 Instead of eggs, Tarnier imagined premature infants in their place—a hopeful solution to the congenitally feeble beings who haunted him.3 Tarnier urged the zookeeper’s instrument maker, Odile Martin, to help him construct a similar “baby-hatching apparatus” in the Paris Maternité Hospital where he worked.4 The two men often giggled over pilsner at the unlikely origin of their human hatchery.

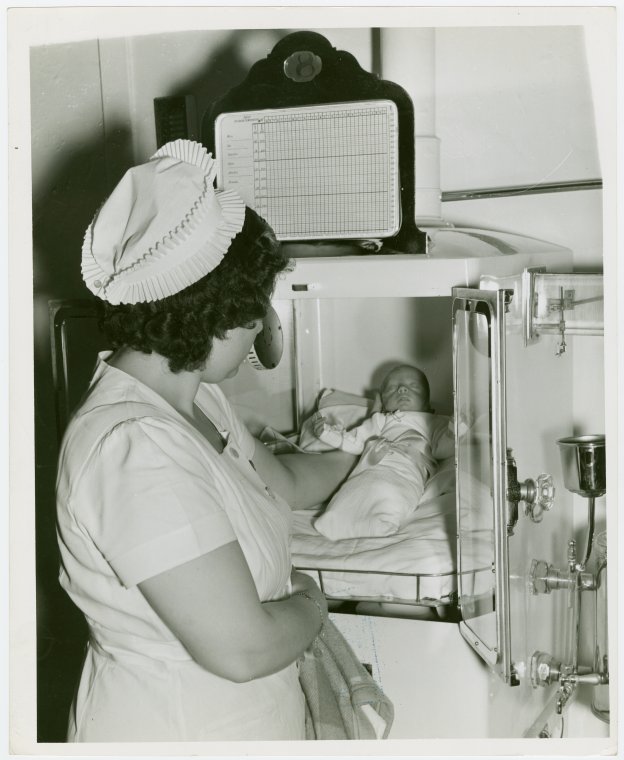

But it would be wrong to say that Tarnier’s invention was simply a solution. It produced prematurity as a medical problem as much as it hoped to eliminate it.5 Tarnier’s most learned pupil, a ducktail-bearded doctor named Pierre-Constant Budin, defined this precarious new life in relation to the system of care it required—“classed as weaklings, and as a rule, the product of premature labor.”6 As Budin wrote in The Nursling, premature infants demanded a new environment, one able to alleviate the harsh realities they faced. Budin identified three simple factors that threatened their lives: temperature, disease, and feeding. Frustrated by “obstinate” mothers, Budin imagined a technological surrogate—a warm, sterile, and nutritious apparatus. He developed a more sophisticated system of heat regulation, monitoring devices, human-milk feedings, filtered clean air, hot water, thermometers, breasts, bottles, spoons, chimneys, envelopes of wood and glass, and more than the usual amount of oxygen. By 1888, Budin had established a special department for weaklings at the Maternité, a ward to house his fleet of prosthetic wombs. And just like that, a machine from the zoo became medical practice.

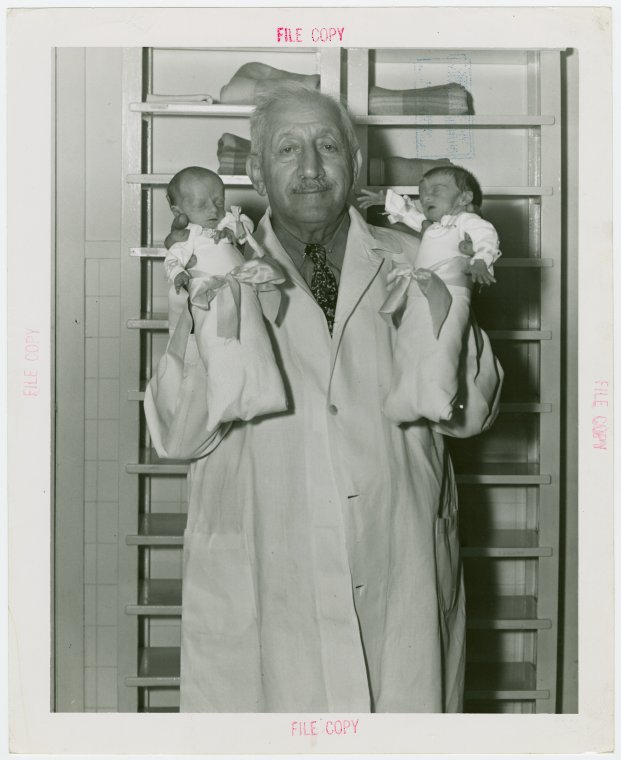

Despite French advances in pediatric care, “in the world of science, nothing really counted until it had received German approval.” So Budin sent his protégé, Dr. Martin A. Couney, to the Berlin Exposition of 1896—a man with a “firm but gentle grasp” only explained by a lifetime of handling canary birds. Situated next to the Congo Village and the Tyrolean Yodlers, Couney’s “Child Hatchery” put six premature infants on display, each loaned from the maternity ward of the Berliner Charité Hospital. To Couney, the live-baby display was “considered a small risk, since they were expected to die in any case.” Spectators paid a modest admission fee to witness feeble lives ensconced in model wombs, and the venture was a financial success. Over the next forty years, Couney and his troupe of infants traveled to Earl’s Court in London (1897), the Omaha-Trans Mississippi Exposition (1898), and the World’s Fairs in Paris (1900), Buffalo (1901), Chicago (1933), and New York (1939). It became, in Couney’s words, an institution, and he emerged at the head of it, the new “Patron of Premies.”7

On good days, Couney was able to sit and watch the crowd stream in and out of his exhibitions. These days pleased him the most. It meant that the machine he worked so hard to create was functioning smoothly. And what a machine it was: union-waged cooks to feed the nurses; registered nurses to supervise the babies and wet nurses to feed them; guides to amuse the tourists; and chauffeurs to shuttle workers back home after their nine-hour shifts had ended. Couney knew his machine was human, too:

One of these machines alone would never save a child. One must know how to care for such an infant. They are taken out of the incubators every three hours, covered in towels, taken into the nursery where they are changed and fed. They must be fed on mother’s milk in order to survive. Science has not succeeded in replacing the mother here. 8

Out of all his employees (though he preferred to call them family), the wet nurses were Couney’s biggest investment—without their milk the whole enterprise would fall apart.9 Each surrogate breast-feeder had an infant of their own at home—a home paid for by Couney. He prided himself on taking special care of these women, “doing his best to protect them from any experience which might make them nervous.”10 Healthy milk meant healthy, confident, well-fed mothers. Some called them spoiled, but with this “good” treatment came vigilant supervision. In a neurotic need for a flow of wholesome milk, Couney would fire any nurse caught eating a hot dog or sneaking a sugary drink.

Despite a marveling public, the medical profession remained skeptical of Couney’s contraptions. Ostracized from the hospital, he found a home for his clinic-cum-sideshow on the boardwalks of Coney Island. Here, Couney was able to exploit amusement in the artificial and passion for the technological. In 1903, Couney launched the “Baby Incubator,” nestled next to the bearded lady and the sword swallower in Luna Park. A year later, he opened a second show in Dreamland. Under the bold, vibrant sign, “All The World Loves A Baby,” streams of visitors waited in line to hand over their twenty-five cents: “to soften the radicalism of an enterprise that [dealt] openly with the issue of life and death, the exterior of the building [was] disguised as an ‘old German farmhouse,’ on its roof a ‘stork overlooking the nest of cherubs’—old mythology sanctioning new technology.”11 Over the course of the next forty years, eight thousand babies passed through the exhibits under Couney’s care. More than six thousand of them grew to be healthy, robust adults.12

II

Batavia, New York, 1956. After tractor manufacturer Massey-Ferguson closed its 850,000-square-foot factory, the city’s unemployment ballooned to 20 percent.13 In an attempt to remedy the city’s economic blight, New York industrialist Joe Mancuso—today, referred to as the entrepreneur’s entrepreneur—bought the property and founded the Batavia Industrial Center (BIC). Rather than seeking another single tenant for the whole space, Mancuso decided to rent it in parts: more tenants, less risk, not to mention the added value of business adjacencies. Soon, a winery, a charity, and a chicken processor filled the empty facility. Mancuso came to work every day to the sound of chirping chicks and began referring to it, jokingly at first, as “the incubator.”

The incubator has since become a staple of the contemporary creative economy: the preferred habitat for today’s struggling “creative class.” In fact, we’re in one right now—sitting at a white circular desk in a glass room in an open plan, after hours. It is safe here: a so-called sensorial oasis.14 With all of the reflective columns, digital screens, whiteboard walls, felt-lined privacy booths, free beer, and snacks, it’s easy to forget about what is happening on the outside. That’s what this space is built for: our bodies and our nascent ideas. For $200 a month, it tries to keep the realities we face outside of it at bay so that we can think, make, and grow untethered. This space will never heal its city, nor does it claim to. While this “creative ecosystem” promises a chance at survival, it allows you to succeed inside only, unable to affect or ameliorate the oppressive conditions that called it forth in the first place. From in here, the crises out there are put into relief.

Now, when companies and institutions call their co-working space an incubator, we know what they mean. Something in infancy is being brought to term—maybe not an infant or fledgling business but a young creative with an idea. But like the medical apparatus, today’s incubators are all still a “menagerie of technologies.” Containment, support, control, service, spectacle, and growth, are all knotted into a single apparatus, a set of relations, a network-in-miniature:15

III

The incubator works to promote life, and in many ways it is this work that allows us to see it not as a discrete and singular machine but as a set of recurring relations in the business of producing people—a coordinated system of production and reproduction intimately connected to the market outside of it. It is a machine for social reproduction, in two senses. First, the incubator mechanizes growth, with the sole purpose of producing new bodies. Second, the incubator’s ability to produce new life relies on activities explicitly performed by women (as nurses and as mothers). It simultaneously casts these activities as labor and reproduces this labor as women’s work. By internalizing the functions of rearing, functions “well trained in the home,” the incubator teaches its laborers that other people’s lives depend on them, making it impossible “to see where [that] work begins and ends.”16 Over time, the reared become the rearers: new bodies, new laborers.

This replication sustains the incubator and helps define it as an infrastructure: an apparatus that facilitates repetition.17 Said differently, infrastructure “orchestrates ritual functions.”18 It trains you to expect it to do its job. You begin to rely on it. And from that, it produces a way of living where we expect it to provide for us, wherever we are. While the incubator sustains the reproduction of life, mapped onto the city, it also describes systems and institutions of support that enable the repetition of less tangible behaviors and flows of material. Planned Parenthood, schools, or even farms (the list could go on) facilitate reproductive health, knowledge, and food production. Federal entitlements, like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, are infrastructures, too: they sustain large portions of the population through checks, visits, prescriptions, etc. We don’t call these services by their infrastructure. We call them by what they do for us and what we get from them. And in this way, through language, we obscure infrastructure and only see its products. However, we cannot talk about infrastructure without knowing what it supports. Or, as Judith Butler asserts of the inverse: “we cannot talk about a body without knowing what supports that body, and what its relation to that support—or lack of support—might be. In this way, the body is less an entity than a relation, and it cannot be fully dissociated from the infrastructural and environmental conditions of its living. No one moves without a supportive environment and set of technologies.”19 The machine outside the body that keeps the body alive is part of the body itself. So, on which infrastructures do people’s lives depend today?

In a capitalist system, an entity’s survival is predicated on its ability to consistently generate profit. The incubator’s drama is a life hanging in the balance. Its walls are glass for a paying audience. Perhaps we must consider innovation, which requires an audience. Or maybe it produces that audience. Dr. Couney made money because it was exciting to watch an infant cheat death. Today, investors bank on creatives’ capacities to quickly generate new tools and sources of revenue. It’s most profitable to be invested in the start-up from the start. Odds are that it won’t survive—in fact, nine out of ten don’t.20 But that hasn’t stopped most people from trying. Sheltered, the incubator offers the luxury of failure. You aren’t granted access to the vast reservoir of support because you are in dire need of resources—you are admitted based on the cultural, creative capital your application promises. The stakes have changed; unlike the infants on the brink of death who circulate in and out of Dr. Couney’s display, today only those who can afford to fail participate.

All machines have the capacity to fail, and when they do, they’re most instructive. From Butler: “The dependency on infrastructure for a liveable life seems clear. But when infrastructure fails, and fails consistently, how do we understand that condition of life? We find that that on which we are dependent is not there for us...We are left without support...It’s not as if we were not vulnerable before; but that vulnerability comes to the fore.”21 This visibility offers an approach to resistance. Rather than denying infrastructure’s fallibility or avoiding the often paternalistic, hierarchical reality of systems of support, Butler invites it. While these systems attempt to control and contain vulnerability, to eliminate its effects with technologies, and to direct labor at the vulnerable source—they tend to dominate, alienate, and insulate—Butler locates vulnerability as the starting point for resistance. To resist means to recognize one’s own dependencies, to bring them into question, and ultimately to challenge them. In Butler’s framework, vulnerability seeds resistance. It germinates struggle and consolidates relations. Rather than seeing vulnerability as a condition of helplessness, resistance begins with connections and solidarities built around it. Recognized as such, vulnerability becomes the site of power and change rather than a condition to alleviate.

IV

What we see in the incubator is infrastructure seeped in the ethos and spectacle of techno-solutionism. It is vulnerability in the hands of a do-gooder, profit-loving showman. The story unearths familiar mythologies: “Prison guards of the past, fighting the pioneers of the future.”22 In Dr. Couney’s case, innovation could only occur outside of the medical establishment, because like most centralized bureaucracies or institutions, hospitals were systemically fortified against change. But this mythology is still as pervasive today. In fact, Newt Gingrich used this metaphor to describe the deep-seated sentiment that gave rise to Trump in the first place—the belief system that private entrepreneurs and the business community (both “pioneers of the future”) are better positioned to serve their customers than governments (“prison guards of the past”). What is claimed to be the harbinger of the future, innovation and evolution, is actually just a system for exploiting vulnerabilities. “Trumpism,” Gingrich writes, “measures results, not effort. It measures outputs, not inputs. A fundamentally different approach from the bureaucratic welfare state.”23 In this mythology, the incubator combines the deferral of death, captivated audiences, and a stream of future profit. Moreover, it displaces risk onto the machine and away from the people it’s supposed to serve. That’s why the first order of business in today’s neo-fascist regime is to “scapegoat the most vulnerable, our fellow Muslims, Mexicans, gay brothers, lesbian sisters, indigenous peoples, black people, Jews, and so on”—an infrastructure of support that is hijacked by this way of thinking doesn’t see vulnerable subjects but thieves: “deliberate inefficiencies” that threaten its success.24

The chants of protest we hear and shout today are expressions of certain needs not met and certain subjects not recognized: “my body, my choice;” “black lives matter;” “education not incarceration.” The history of the incubator is proof that infrastructure and methods of support develop from needs and result in real environments. Need rearranges the world. What differentiates a need from a want, a desire, or a wish, is that when a need goes unfulfilled, the body or mind perishes. Need begs, often quite desperately, for external recognition and materialization. Privilege, on the other hand, is a blindness to one’s own needs or blindness to the fact that one’s needs are being met on their behalf. So we repeat: the machine outside the body that keeps the body alive is part of the body itself. The threat, we feel so urgently right now, is that this machine will get turned off.

-

Since 2015, we : (pronounced “colon”) have been kept warm in the GSAPP Incubator at the New Museum’s NEW INC for emerging artists and designers in New York. ↩

-

A. J. Liebling, “Patron of Premies,” The New Yorker , June 3, 1939, 20–24, link. ↩

-

France had one of the highest infant mortality rates in Europe at the time (223 deaths out of 1,000 births) as well as a declining birth rate. Jules Simon, a popular French statesman, famously proclaimed: “France loses a battalion [of soldiers] per year because it lets the infants of the poor die…We let 180,000 infants perish each year. Does France have 180,000 too many that we allow such assassinations?”

See Jeffrey P. Baker, The Machine in the Nursery: Incubator Technology and the Origins of Newborn Intensive Care (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1996); Jeffrey P. Baker, “The Incubator and the Medical Discovery of the Premature Infant,” Journal of Perinatology (2000): 321–328; and Gregory Macris, “Strategic Implications of Declining Demographics: France: 1870–1945,” US Department of State, (Newport, RI: US Naval War College), link. ↩ -

Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 51. ↩

-

Consider Paul Virilio’s notion of the “integral accident:” “If in fact, no substance can exist in the absence of an accident, then no technical object can be developed without in turn generating ‘its’ specific accident: ship=ship wreck, train=train wreck, plane=plane crash. The accident is thus the hidden face of technical progress.” From Virilio, Politics of the Very Worst (New York: Semiotext(e), 1999), 89. ↩

-

Pierre-Constant Budin, “Lecture One,” The Nursling (London: Caxton Pub. Co., 1907), 4, link. ↩

-

Liebling, “Patron of Premies.” ↩

-

Dr. Couney quoted in “‘Mechanical Mother’ Saves Lives of Infants,” Modern Mechanics and Inventions (March 1931): 100–104, link. ↩

-

Dr. Couney’s wife, Annabelle May Couney, was a nurse that specialized in the care of premature infants; his daughter Hildegarde, also a trained nurse who worked for her father, spent the first few months of her life in the incubator display; Madame Louise Recht, trained by Dr. Budin, was Couney’s head nurse and “chief aid” throughout his entire career and lived with the family in the on- and offseason. Those infants who survived their term were called “graduates.” See William A. Silverman, “Incubator-Baby Side Shows,” Pediatrics, vol. 64 (August 1979): 127–141. ↩

-

Liebling, “Patron of Premies.” ↩

-

Koolhaas, Delirious New York, 53. ↩

-

Michael Brick, “And Next to the Bearded Lady, Premature Babies,” New York Times, June 12, 2005 link. ↩

-

“Joseph Mancuso,” International Business Innovation Association, link; and Darren Dahl, “How to Choose an Incubator,” New York Times, January 26, 2011, link. ↩

-

SO-IL, “Workspheres.”

An incubator contains and supports vulnerable life. It materializes power: power exercised in the ability to foster life.[^16] The crying infant personifies vulnerability, a so-called powerless subject born out of crisis. A life in crisis is always dependent, whether on the glass walls that surround it or the hands of the physician who cradles it. Dependency promises, or rather expects, growth: “you’re kept warm only because you’re expected to hatch.”[^17] ↩ -

“Wherever we turn we can see that jobs women perform are mere extensions of the housewife condition in all its implications. That is, not only do we become nurses, maids, teachers, secretaries—all functions for which we are well trained in the home: isolation: the fact that other people’s lives depend on us, or the impossibility to see where our work begins and ends, where our work ends and our desires begin.”

From Silvia Federici, “Wages Against Housework,” 6. See also, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (New York: PM Press, 2012). ↩ -

Our definition of infrastructure uses Martin’s “that which repeats” but proposes a slightly different understanding: “that which enables repetition.” For instance, a bridge might repeat, but it ultimately enables the flow of traffic. Once the system is set up, things (materials and behaviors) can repeat. You know that when you open your faucet, water will come out. What infrastructure does, though, is let you get water without having to think about the reservoir or the pipes that deliver it—“it tends to come into view only when repetitions cease.” Reinhold Martin, The Urban Apparatus: Mediapolitics and the City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 25. ↩

-

Martin, Urban Apparatus, 25. ↩

-

Judith Butler, “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance,” in Vulnerability in Resistance, ed. Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, Leticia Sabsay (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 3. ↩

-

Neil Patel, “90 Percent of Startups Fail: Here’s What You Need to Know About the 10 Percent,” Forbes, Jan 16, 2015, link. ↩

-

Judith Butler, “Vulnerability and Resistance,” Lecture, California Institute of the Arts, March 4, 2015, link. ↩

-

Newt Gingrich, “Understanding Trump and Trumpism: Part I,” transcript of speech at the Heritage Foundation, 2017, link. ↩

-

Gingrich, “Understanding Trump and Trumpism.” ↩

-

Cornel West, “Cornel West on Donald Trump: This is What Neo-Fascism Looks Like,” Democracy Now, 2016, link. ↩

Wade Cotton is an architectural designer and teacher living in Brooklyn. His projects and research focus on the confluence of perception, language, and politics as rendered in the built environment.

Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt is managing editor of the Avery Review and assistant director of Columbia Books on Architecture and the City.

They are two of the eight co-founders and editors of :(pronounced “colon”), a workshop on architectural practices and ideas based in New York City.