Sometime after its designation in 2000, the Speakers’ Corner—the only state-authorized space in Singapore where public speech is allowed without permit—was criticized for being purely a gesture. Prominent activists, scholars, and nongovernmental organizations condemned the demarcated space as, among other things, “an exercise in tokenism;” “an example of the familiar tactic of allowing limited liberalization while retaining tight control;” and “a window dressing attempt of the government to deceive the international community.” 1 Intersecting with the emergence of virtual political forums and blogs, the corner was further suspected to be an instrument to lure Internet-based dissent out into the open. 2

The critique was not without some validity. The space was operated under tight regulations, denying its claim to freeness. To deliver a speech at the space, you—who first of all must be a Singaporean—were required to register in advance at the adjacent police post, a process that includes stating your topic. Hence, even if no permit was required, registration was. Issues related to racial or religious matters were prohibited. If your registration was accepted, you were finally able to speak at the space, using no languages other than Singapore’s official ones (English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil) and with no amplification devices or visual aids such as banners or placards. Your allowed time slot would be sometime between 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m.3

What makes Speakers’ Corner notable has less to do with its urbanism than its special treatment under Singapore’s Public Entertainments and Meetings Act (PEMA). This law regulates licenses for arts and public entertainment in public spaces, including, from before 2009, any play reading, recital, lecture, talk, address, debate, or discussion.4 Public speeches at the Speakers’ Corner are exempted from these licensing requirements.5 This exemption, however, is shadowed by many other existing laws—with the Penal Code being the most spatially critical.

The Penal Code, which defines as “unlawful” any assembly of five or more persons protesting the government or any public servant, has been influential in defining the fate of protests inside and outside the Speakers’ Corner. On the one hand, the law creates ongoing fear about collectively voicing dissent in public. No event exemplifies this more than “Occupy Raffles Place,” a protest held on October 15, 2011, in Singapore’s financial center, which received three thousand followers on Facebook with seventy-five accounts indicating they would attend. In the end, the only “attendees” who reportedly showed up were five members of the press, one police truck, a couple of police, and a handful of pigeons. Without any protesters, the protest never happened—even the organizers did not present themselves.6

On the other hand, the Penal Code has produced unexpected forms of protest that have tactically exploited the code’s loopholes. For instance, a silent protest by members of the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) on August 11, 2005, held in front of the headquarters of the Central Provident Fund Board (Singapore’s government agency that administers the state-managed pension fund) cracked the law’s quantitative definition. The protest gathered four persons—one below the lawful cut-off—to stand on the street with provocative messages demanding transparency and accountability for fund management written on their T-shirts. As if making a joke out of the law, two additional members of the protest opened a book stand selling political tracts and shouted against the government, just far enough away from the other four members to prevent them from being grouped together as an unlawful assembly.7

In a way that may have gone unforeseen by both the government and its critics, many moments in the Speakers’ Corner’s sixteen-year history have embraced the spirit of the latter protest more than the former. Since 2000, this official space for public speech has evolved into a contested (and on occasion, fully repressed) site that has tested, and to some extent expanded, the limit of freedoms of speech, expression, and assembly—rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Singapore, and yet the perennially top-listed human rights issue in the country’s entry of the Human Rights Watch World Report.8 Critical in activating the rights to public speech is the effort to produce spaces of resistance within, and beyond, the Corner’s architectural boundaries.

An Old Wooden Drawer

Twenty-five people registered to deliver speeches at the Speakers’ Corner on its inauguration day, September 1, 2000, and a decent cadre of curious spectators came to listen.9 It was a new experience for everyone. The idea for dedicating such a space to public speech had been raised one year before, by Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew.10 It was subsequently opposed by Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, who stated that Singaporeans were not yet ready for such an experiment.11 But after weighing the management of potential risks, the executive government headed by Goh decided to give it a chance. A careful study of the Speaker’s Corner at Hyde Park, London, was undertaken as a precedent for the Singaporean version’s operation and management. Nevertheless, the government imposed distinct fundamental rules from its sister space, such as the need for registration and a restriction against delivering racial or religious speeches.12

The space was inserted into Hong Lim Park, a historic public park in which many rallies and political speeches were held during the independence struggle in the 1950s and 1960s. Despite its symbolic value, the park is physically banal. Its terrain is relatively flat, and its ground is mostly covered in grass, with few trees or other plantings. No canopies were built to protect crowds from the tropical heat; no amplification was provided to help the speakers’ voices be heard. While the park is advantageously located within the city center, it is surrounded by busy roads on its four sides. The unassisted human voices are isolated inside, amid the noise of the city; bushes and trees fill the perimeter, making activities less visible from outside. The existing structures inside the park include the Kreta Ayer Neighborhood Police Post, where the registrations to speak were administered, and a community center with a decent-size open stage facing the Corner’s area—though this stage is slightly outside of the designated boundary. What designates the Speakers’ Corner has less to do with architectural features than with an abstract line that limits its boundary, some wood panels bearing the name “Speakers’ Corner,” and a larger board displaying a list of the Corner’s rules, including its demarcated limits.

One of the speakers who spoke on the opening day was bus driver Ong Chin Guan, who came the night before to observe the scene and hid an old wooden drawer in the bushes. The New York Times attended the opening day and reported on Ong’s subtle intervention: “When the sun came up Friday morning, he pulled his old drawer from the bushes, placed it squarely in the center of Hong Lim Park, climbed up onto it and began to speak.”13 Ong’s drawer, evoking the classic cliché of speaking from a soapbox, proved to be an important gesture that immediately redefined the emptiness of the Speakers’ Corner, desterilizing the space and transmitting his speech more clearly to his audience.

“If I Were to Go to the Speakers’ Corner and Clench My Fist in the Air, Is That a Demonstration, Sir?”

The Singapore Parliament held a hearing on March 5, 2001, regarding the use of the Speakers’ Corner. Ho Peng Kee, the minister of state for Home Affairs, was invited to answer questions. The session veered quickly into ontological questions on the very nature of speech. Simon Tay, a nominated member of the legislature, asked the minister, “What is the difference between speech and demonstrations? And whether per se if I were to go to the Speakers’ Corner and clench my fist in the air, is that a demonstration, sir?”14

The physical boundary of the Speakers’ Corner was clearly demarcated, but its performative limit was ambiguously defined. The use of “speakers” in the name itself seems to imply that the space prioritizes the orality of speech. What about the bodily gestures that support its verbalization? Are they secondary? How do we separate bodily performativity from the linguistic performativity of a speech act? Could not the body, to some extent, speak in its own right? The questions become much more complicated when we try to separate demonstration and speech as two completely different activities, in part because the former often implies more bodily performativity than the latter.15

The hearing had been triggered by a specific case. A group of people had gathered on December 10, 2000 at the Speakers’ Corner to commemorate International Human Rights Day as well as to protest against Singapore’s Internal Security Act (ISA), a law that allows the government to arbitrarily enforce detention of any citizen who is suspected of endangering public security. Before and during the speeches, some of the participants—more than four people—raised their fists and shouted “Abolish ISA!” While no complaint was received from the public about the gathering that day, a photograph posted on the website of the Think Centre, one of the two institutions that organized the gathering, provided the necessary evidence. A letter to the editor was published four days later in a local newspaper, demanding that the police take action against the protesters.16

Refusing to answer Tay’s incisive question explicitly, the minister pointed out other of the gathering’s problems. As the Speakers’ Corner is not exempted under the Penal Code, he said that the event, which consisted of more than four people, could be regarded as an unlawful assembly since it could be construed as a demonstration rather than simply an act of public speech. Tay, unsatisfied with this answer, followed up with further possibilities for interpreting the space differently: Could five or more people register to speak on the same topic, either sequentially or at the same time? If any speaker invites friends to come and support his or her speech, would that be considered organizing an illegal assembly? If any speaker gives a speech and five or more people follow him and start clenching their fists and saying, “Yes, we agree with you,” would that constitute an illegal assembly?17

The government ended the case by issuing a stern warning to two activists from the Think Centre and the Open Singapore Centre, the institutions that organized the event, and this government action provided clearer language in articulating the performative limit of the space. Inside the Corner, the freedom of speech provided by the space, which emphasized orality, had to be read separately from the freedoms of expression and assembly, which involved more bodily performativity. Demonstrations, which to some degree overlap with speeches, belonged to the latter categories and were therefore not allowed. At the same time, the decision showed that the Corner was a place where only individual speakers were able to speak. To quote the editorial of the Think Centre’s website a day after the warning was given, the Speakers’ Corner suddenly became smaller.18

Speakers Cornered

In another instance, a group of protesters affiliated with the Singapore Democratic Party disrupted the performative limit of the Speakers’ Corner through what could be considered a kind of double play, countering the indictment of being an unlawful assembly while expanding their protests beyond the Speakers’ Corner. This group, which also conducted the silent protest against the Central Provident Fund Board in 2005, held a three-day protest with an innovative twist—they would initiate the protest through speech at the Corner and then individually march outward into the city streets. To spread the message without having to deliver speeches outside of the Corner, they became the message by wearing similar white T-shirts with “Democracy NOW” written on their fronts.19

The protest was held in the context of the IMF-World Bank annual meetings hosted by Singapore in September 2006. While protests have been regularly conducted around IMF and World Bank meetings, the host state insisted on sterilizing public spaces from any resistance by reemphasizing its ban on outdoor protests. As an alternative, the state dedicated a small corner in the lobby of the Suntec Convention Center, where the annual meetings were held, to accommodate indoor demonstrations. Like the Speakers’ Corner, the protesters had to register and follow many other rules of protest. The government further prohibited the International People’s Forum (IPF), a counter forum organized by a coalition of nongovernmental organizations, to provide alternative readings of the annual meetings. The forum was finally offshored to Batam, an Indonesian island located forty-five minutes by ferry from Singapore.20

Criticizing the stringent rules, the three-day protest emanating from Speakers’ Corner was held to protest the banning of protests during these particular meetings, as well as in the general Singaporean context. Many foreign journalists were in town, ready to report any incidents surrounding the meetings to global audiences. This situation was exploited by the group to gain wider coverage.

The protesters gathered at Speakers’ Corner on the morning of September 16. The crowd surrounding the protest was dominated by two groups. The first one consisted of journalists and reporters who were mostly equipped with cameras. The other group was police officers, many of whom were wearing plain clothes. After Chee Soon Juan, a member of the protest and also the leader of the Singapore Democratic Party, delivered his speech, the protesters dispersed toward the streets. They were, however, prevented by police officers from moving out of the Speakers’ Corner. The officers, using their own bodies, encircled each of the protesters. The protesters responded in a similar manner, saying that if they were not allowed to walk anywhere like common citizens, the officers had to simply arrest them.

Detaining the protesters would mean taking a legal action against them and would have produced much more controversy in media reports. The state took the less risky step of keeping the protesters around the park—limiting their march without conducting any legal pursuit. The dedicated Corner for Speakers was utilized as a space for cornering speakers. After the protest, Singaporean filmmaker Martyn See published a documentary that showed different key events of the protest. It was titled Speakers Cornered.21

Relaxation

While the protests of 2006 certainly brought attention to Speakers’ Corner, participation overall had plunged drastically since the space was inaugurated. It rarely enjoyed more than one speaker each day. Already in January 2001, only twelve registrations to speak during the month were recorded at the police post—such a small number compared to the opening day that a journalist termed it “the silent corner.”22 The inclusion of performances and exhibitions in 2004 as authorized activities within the corner, in addition to speeches, did not especially increase the use of the Corner.23

Possibly in response to this loss of interest—though likely also in reaction to the focus of the media and public opinion on the 2006 protest—the government offered a “relaxation,” as many called it, of the Speakers’ Corner rules in 2008. On the National Day Rally, an annual speech by the prime minister of Singapore, Lee Hsien Loong, in commemoration of Singapore’s independence, announced the news:

So I think we should allow our outdoor public demonstrations, also at the Speakers’ Corner still subject to basic rules of law and order, still stay away from race, language, and religion. I think we will still call it Speakers’ Corner, no need to call it demonstrators’ corner, but we will manage with a light touch.24

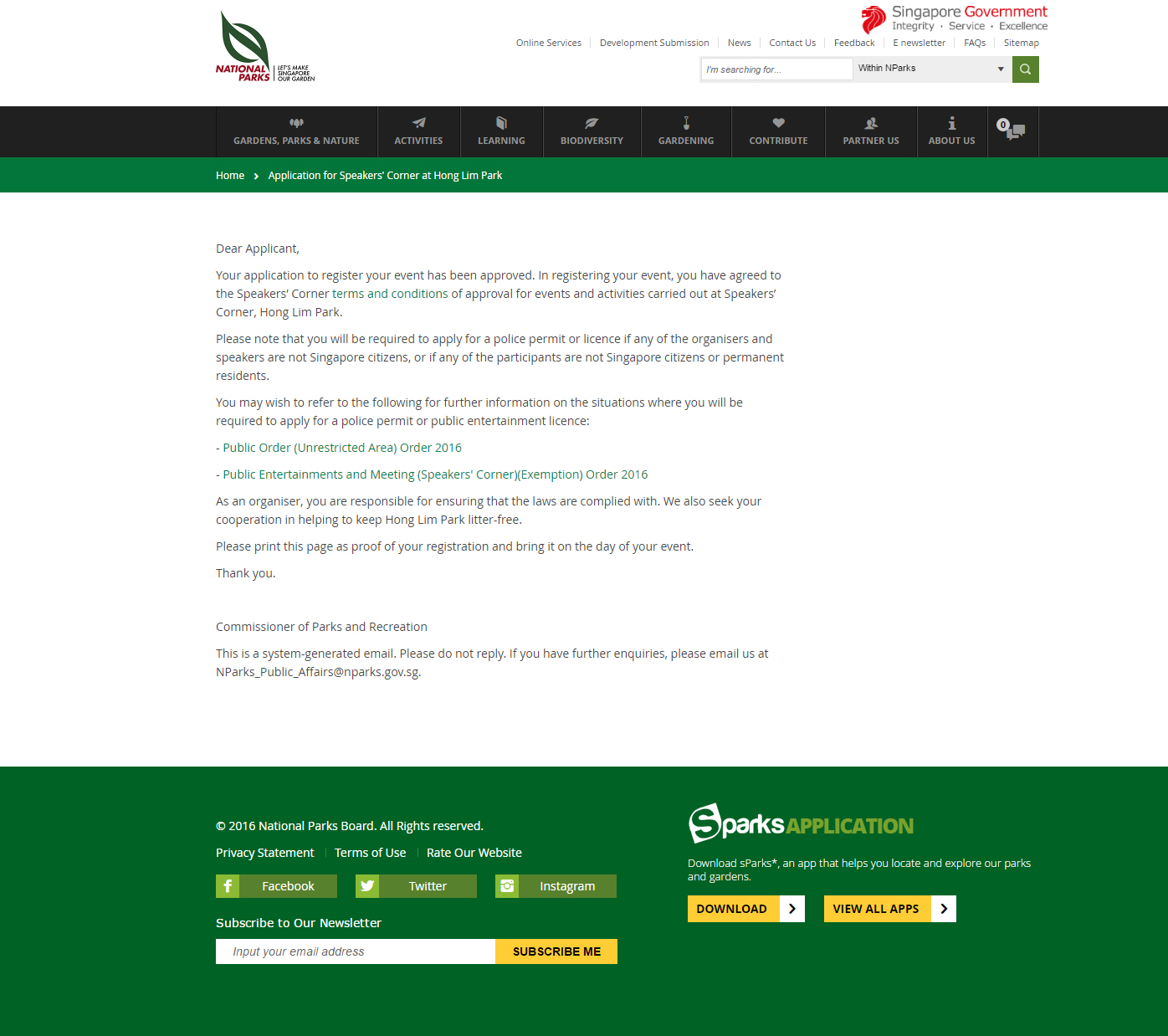

Beginning September 1, 2008, the National Parks Board would take over the administration of the venue from the police. The speakers would only have to register online on the National Parks website, similar to applying for barbecue pits in public parks. The park would be open twenty-four hours. Banners, placards, and handheld loudspeakers would also be allowed between 9:00 a.m. and 10:30 p.m. More importantly, public protests and demonstrations would finally be authorized.25

This good news, however, lasted less than a year. In April 2009, the parliament passed the Public Order Act, under which any public assembly has to apply for a police permit, regardless of the number of persons involved. In other words, the new act enabled the government to abandon the quantitative definition of an unlawful assembly as previously defined by the Penal Code. Furthermore, the act also provides police officers with authorities to direct a person or a group of persons to move out of a designated area and, if the related party is not cooperative, to conduct arrests. Another part of the act empowers police to stop any person from filming, distributing, or exhibiting films of law enforcement activities.26 This ban on filming security operations was accompanied by new measures that filmed speakers. The police authority installed five closed-circuit televisions in different locations at the park, mainly facing the Speakers’ Corner area, a few months before the new act went into effect.27

The relaxation thus felt like one step forward, two steps back. While the Speakers’ Corner was now defined as an “unrestricted area” where assemblies including group demonstrations could take place inside the space without a permit, the exemption seemed to justify tightening the government’s control of other public spaces. Moreover, the Corner is only exempted from the need for permit but not from other components of the act, such as the move-on powers.28 Applying the Public Order Act to the 2006 protest demonstrates its significant implications, as it could have prevented that protest entirely. First, the members of the protest could now be deemed an unlawful assembly when they moved outside the Speakers’ Corner. Second, even if they had remained inside the Corner, they could be asked to “move on,” rendering their activities public disorders. Third, their video recordings could be banned or halted, preventing the creation and dissemination of any visual evidence documenting acts of state repression.

A Little Red Dot

The Pink Dot, an annual event held at Speakers’ Corner since 2009 to support LGBT rights, has involved more participants every year—multiplying from one thousand people in 2009 to twenty-eight thousand in 2015. The spokesperson for the 2016 Pink Dot, Paerin Choa, has argued that the number of attendees is no longer even the principle means of judging such an event in Singapore. “The park has been filled to capacity since last year, so there is really no need to report the numbers, which is why this year we want to focus on the messages instead.”29 The Pink Dot is one among many events—or demonstrations, if you will—which would not have been authorized if the relaxation in 2008 had not been enacted. The Corner has enjoyed more activities after the change. More importantly, it has witnessed more participants and more variety—both in the issues addressed and in the forms of demonstration and protest undertaken.

The level of participation in the 2016 Pink Dot surpassed the maximum capacity that can be contained at Speakers’ Corner. Focusing on active participation rather than the amount of participants, the event organizers decided to replace torchlights (which had been used in the previous three years) with round pink placards where participants could write their thoughts. In the climax of the event, all participants were asked to raise their placards up together. Seen from above, the crowd created one big pink dot that consisted of tens of thousands of little dots. After the event, participants could bring their placards home, keeping an explicit reminder of why they had taken part.30

On November 1, 2016, five months after the event, the government amended the Public Order Act. In its “Unrestricted Area” chapter, under which Speakers’ Corner is regulated, the existing license exemptions for Singapore citizens are extended to Singapore entities. This means that local companies and NGOs can now organize or assist in organizing events at the Corner without a permit. Conversely, non-Singapore entities will now need a permit if they want to engage in such activities.31 In the case of the Pink Dot this is a highly influential move, as many of its sponsors are global companies such as Google, Apple, Yahoo, and Bloomberg. The minister of Home Affairs, in the official press release, said:

How the organizers will navigate the 2017 event in light of this new change remains to be seen. Very likely the organizers will find ways to subvert it, like the way they created the name “Pink Dot” by appropriating the “little red dot,” one of Singapore’s nicknames, and recoloring it with their own meaning.32 The original term refers to the common red dot symbol used in world maps to indicate a country, whose size, in the case of Singapore, often covers the whole of its geographical area. Ironically, Lee Hsien Loong used the term in the 2008 speech in which he outlined the “relaxation” changes made to the rules governing Speakers’ Corner, meant to provide wider space for expression and participation: “But please remember, even in the cyber age, some things don’t change. In 50 years’ time, Singapore will still be a little red dot.”33

Nevertheless, some things did change. What is perhaps more important than the changes themselves is the way in which different tactical efforts, produced to navigate the state’s desire to isolate spaces of speech, have gradually forced those same changes. Different forms of resistance at the Corner have displayed dissent but have also exposed flaws and cracks in the state’s instruments of control, allowing them to be contested (and sometimes to crumble) under their own definition. Such resistances might produce larger impacts as they tend to force the state to keep changing its own standing. If the Corner, which is designated as a single, small space for public dissent, is emblematic of the unchanging little red dot; it is the collective multiplicities of its recoloring—the persisting back-and-forth negotiations between the citizens and the state—that will continually redefine the physical and performative boundaries of the Corner and will help expand the limit of the freedoms of speech, expression, and assembly in Singapore.

-

Li-ann Thio, “Singapore: Regulating Political Speech and the Commitment ‘To Build a Democratic Society,’” International Journal of Constitutional Law, vol. 1, no. 3 (July 1, 2003): 522; Joshua Kurlantzick, “Love My Nanny,” World Policy Journal, vol. 17, no. 4 (2000): 69; Yap Swee Seng, “Let Singaporean Voices Be Heard,” Think Centre, link. ↩

-

Terence Lee, “Media Governmentality in Singapore,” in Democracy, Media and Law in Malaysia and Singapore, ed. Andrew T. Kenyon, Tim Marjoribanks, and Amanda Whiting (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), 40. ↩

-

Singapore Parliamentary Report (April 21, 2000), vol. 72, cols. 20–30. ↩

-

The Schedule, Public Entertainments and Meetings Act (Cap. 257, rev. Ed. 2001), available at link. Lectures, talks, addresses, debates, or discussions have been excluded as forms of “public entertainment” since the enactment of Singapore’s Public Order Act in 2009. ↩

-

Public Entertainments and Meetings (Speakers’ Corner) (Exemption) Cap 257, § 16, Order 3, (Sept. 1, 2000). ↩

-

Ting Ying Hui, “Singapore: Why Occupy Raffles Failed,” Asian Correspondent, October 25, 2011, link; Belmont Lay, “Occupy Raffles Place Fail [sic],” New Nation, October 16, 2011, link. ↩

-

“Silent Street Protesters Versus Anti-Riot Police in Singapore,” YouTube video, posted by Singapore Rebel, 10:51, July 11, 2015, link. ↩

-

Human Rights Watch has included Singapore as an independent entry since its 2008 edition of World Report. Freedom of speech, expression, and assembly tops the annual report from the 2008 edition to the latest 2016 edition. Human Rights Watch, World Report (2008; 2009; 2010; 2011; 2012; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016), available at link. ↩

-

Seth Mydans, “Soapbox Orators Stretch the Limits of Democracy,” New York Times, September 2, 2000, link; Chua Lee Hoong, “Slew of Policy Changes Spells Good News,” Straits Times, September 2, 2000. ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew served as the state prime minister for three decades, before acting as the senior minister from 1990 to 2004. His proposal to create the Speakers’ Corner was first published at William Safire, “The Dictator Speaks,” New York Times, February 15, 1999, link. ↩

-

“S’pore ‘Not Ready for Speakers’ Corner,’” Straits Times, September 12, 1999. ↩

-

Singapore Parliamentary Report (April 21, 2000), vol. 72, cols. 20–30; Singapore Parliamentary Report (April 25, 2000), vol. 72, Annex A. ↩

-

Mydans, “Soapbox Orators Stretch the Limits of Democracy.” ↩

-

Singapore Parliamentary Report (March 5, 2001), vol. 73, col 69. ↩

-

See Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 8–10. ↩

-

Chee Soon Juan, “Human Rights: Dirty Words in Singapore,” in Activating Human Rights, ed. Elisabeth Porter and Baden Offord (Bern: Peter Lang, 2006), 165–166; Singapore Parliamentary Report (March 5, 2001), vol. 73, col. 69. ↩

-

Singapore Parliamentary Report (March 5, 2001), vol. 73, cols. 69–71. ↩

-

“Speakers’ Corner, What Now?” Think Centre, March 28, 2001, link. ↩

-

Martyn See, “Speakers Cornered” (2006), YouTube video, 10:51, posted by Singapore Rebel, June 22, 2015, link. ↩

-

Theresa Wong and Joel Wainwright, “Offshoring Dissent,” Critical Asian Studies, vol. 41, no. 3 (September 2009), 404–414. ↩

-

Martyn See, “Speakers Cornered.” ↩

-

Mahesha Thenabadu, “The Silent Corner,” Today, February 6, 2001, 3. ↩

-

Azrin Asmani M. Nirmala, “Activists Laud Easing of Public Speaking Rules,” Straits Times, August 24, 2004; Chua Mui Hoong, “Sleepy, oops, Speakers' Corner: It's Now Up to Citizens to Respond to the Chance Given by Government,” Straits Times, August 29, 2008. ↩

-

“Transcript of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Rally 2008 Speech,” Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, August 17, 2008, link. ↩

-

Sue-Ann Chia, “Ban on Outdoor Demos Eased from Monday,” Strait Times, August 26, 2008. ↩

-

Public Order Act (April 28, 2009); “Public Order Act Booklet,” Ministry of Home Affairs, November 1, 2009, link. ↩

-

Andrew Loh, “Even in the Cyberage, Some Things Don’t Change,” the Online Citizen, July 27, 2009, link. ↩

-

Public Order Act. ↩

-

Nurul Azliah, “Pink Dot Singapore 2016 Attendance ‘Exceeds’ Hong Lim Park’s Capacity,” Yahoo Singapore, June 4, 2016, link. ↩

-

Azliah, “Pink Dot Singapore 2016 Attendance ‘Exceeds’ Hong Lim Park’s Capacity.” ↩

-

“Review of Speakers’ Corner Rules,” Ministry of Home Affairs, October 21, 2016, link.

The Government’s general position has always been that foreign entities should not interfere in our domestic issues, especially political issues or controversial social issues with political overtones. LGBT issues are one such example.[^32]

-

“Transcript of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Rally 2008 Speech.” ↩

Robin Hartanto Honggare studies critical, curatorial, and conceptual practices in Architecture at Columbia GSAPP. His current research focuses on architecture, nationalism, and internationalism in Southeast Asia.