The 1964–1965 World’s Fair was dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe” and its theme was “Peace Through Understanding.” The whole production—the assemblage of buildings, artwork, and programming—was intended as a tour de force of state representation and a surround experience that virtually anticipated IMAX today. Among the most iconic exhibits was the New York State pavilion, which was comprised of the Tent of Tomorrow, the “Astro-View” observation towers, and the Theaterama.

You might know it like this.

But very few people caught a glimpse of it like this.

The Theaterama screened a 360-degree panoramic film about New York State, and the ’60s-future structure that contained this display remains intact, if decrepit, to this day. For the opening of the fair, its exterior façade was plastered with large artworks by famous artists of the day, including Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, and Andy Warhol. Of all the works, Warhol’s contribution, titled Thirteen Most Wanted Men, pushed buttons. It traded on publicly available imagery; in its own act of economic redundancy, the painting was composed simply as a grid of blown-up mugshots already on view in any post office. But the combination of heroically scaled criminal subjects, the deadpan aestheticization of appropriated content, and what were considered by some to be homoerotic undertones made for a Trojan horse of a gift to the fair’s organizers.

Governor Nelson Rockefeller demanded its covering or removal, and Warhol dutifully painted a sheet of silver over the mural.1 This was Warhol’s only public art piece, on view for all of forty-eight hours. One can imagine his blasé reaction to how he’d mirrored the organizers’ own logics: his subjects were unwitting, and their portraitists were not just remote to his work but on the state’s payroll. The work was essentially paid for by the state, twice. Along the way, thirteen men fell under the overlapping purviews of law enforcement, of a collective media spectacle of surveillance, of state finances, and of public space.

Today, we can find other such economic redundancies in the finance, imagery, and sensibility of convicted and suspected criminal citizens: businesses like CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America, or CCA) expertly aggregate them. A publicly traded company, CCA describes itself variously as “the nation’s largest provider of corrections management services to government agencies” (2008), or as “America’s largest owner of partnership correctional and detention facilities” (2014). 23 In fact, in 2012, CCA was already the largest for-profit private prison company in the country when it sent a letter to forty-eight state governors offering to buy and operate their public prisons. The catch: CCA’s proposed purchase involved a twenty-year operating contract, which stipulated that states guarantee a 90 percent occupancy rate for the entire term or else be obligated to pay the company for unused prison beds (a “low-crime tax” that essentially penalizes taxpayers when prison incarceration rates fall). No state took CCA up on its offer. But many private prison companies have been successful in inserting occupancy guarantee provisions into prison privatization contracts, requiring states maintain high occupancy levels in their private prisons.4 This is one measure by which prison populations in the United States are growing, along with prison construction rates, occupancy rates, and the privatization of a public-sector responsibility.

Over the last century, the numbers of incarcerated in US state and federal prisons have grown from 57,070 (1900) to 329,821 (1980) to 1,312,354 (2000). This reflects a much higher rate of incarceration than population growth, from 69 per 100,000 (1900) up to 478 per 100,000 (2000).5 The Centre for Research on Globalization has reported that there are now approximately two million inmates in state, federal, and private prisons throughout the country. According to California Prison Focus, “no other society in human history has imprisoned so many of its own citizens.” Since 1980, we also observe that the rates are disproportionate in different states. In 2010, around 900 Louisianans per 100,000 were in prison, around 650 in Alabama, but 150 in Minnesota.6 Twelve years ago, there were only five private prisons in the country, with a population of 2,000 inmates; now, there are 100, with 62,000 inmates. It is expected that by the coming decade, the number will hit 360,000.

All this runs counter to what one might expect given the advent of new technological means by which prisoners walk, in effect, outside prisons today.7

Take the ExacuTrack® One, the smallest circle inside which a convicted criminal might live. Developed by the BI Corporation, the device provides a sort of DNA for a wide range of competing electronic monitoring, or “EM,” products that link private bodies with state and federal probation programs. Use has grown rapidly since the proliferation of broadband Internet networks in the mid-1990s.8 BI describes the ankle-worn device as:

One of their promotional stock photos shows the device modeled on a white woman in mom jeans, sitting on a park bench. BI writes:

ExecuTrack® One combines autonomous GPS, assisted GPS, and AFLT (Advanced Forward Link Trilateration), to create dependable monitoring information. The integration of monitoring systems allows ExecuTrack® One to provide a true location for the supervised person, even in challenging conditions, like when they are indoors, driving or moving in or between very tall buildings.9

Importantly, and unlike the GPS we might use to find our way around in a rental car, the device maps its “offender’s” movements in space but also in time—creating the ability to enforce curfews or to ensure that its subject is moving toward work at an appointed hour. Architecture registers in the ad copy of electronic monitoring, particularly in its reflection of our contemporary sense of privacy: if our private lives have long been defined by thresholds of access, we now measure it in terms of informational resolution. Where resolution can determine location with greater precision in space and in time, in plan and in section, then the mechanisms of public surveillance have most fully transitioned from mere detection to data collection.

ExacuTrack® One adds an option of…a “beacon”…currently in the patent approval process. (It) can be mounted in the offender’s home…where the ExacuTrack® One system automatically switches from GPS tracking to radio-frequency monitoring…When the person being monitored leaves the beacon’s target zone, it instantly reverts to multi-technology GPS tracking.10

Debates focus on EM’s effects on recidivism, its financial merits, and its moral aspects. But this switch from radio-frequency to GPS carries a spatial operation, as wearers extend the domain of monitoring into their own homes or workplaces. EM borrows private spaces for programs that would otherwise be contained within and paid for by the public, in publicly administered spaces of monitoring or incarceration. This presents another redundancy in space and finance, as prison functions are effectively outsourced to the city and to private spaces. As spatial, financial, and societal circles intersect, so do terms like “value” and “sensibility”: the refined resolution of tracking that erodes privacy also corresponds with widening circles of financial assets in the monitored. These overlapping circles in the space and time of the city seem not by-products of the monitored but instead monitoring’s ulterior motives. Where these constraints overlap is a glimpse of our collective ongoing crisis of “enclosure” itself.

BI’s ad copy elaborates on this further:

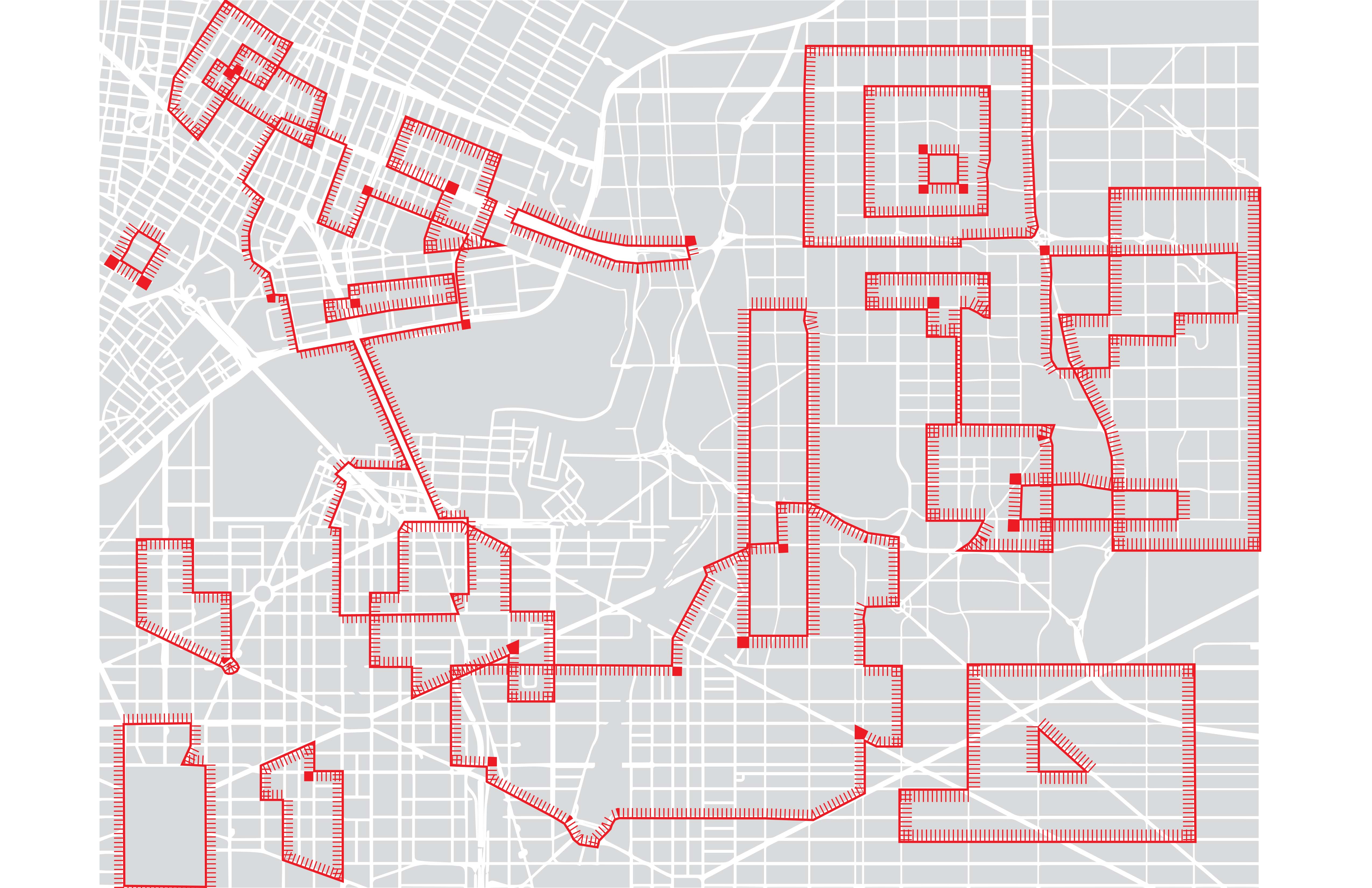

The ExacuTrack® One allows officers to draw a precise monitoring zone in any shape through the use of [proprietary online maps]…Warnings can be sent [and officers can] create voice messages to send to offenders through the ExacuTrack® One tracking unit…(a) bidirectional communication system (that) can be used as an appointment reminder or to alert an offender when they are entering a zone which has been deemed off-limits.11

Seamlessly, the anklet extends its architectural performance to stretch across scales from the body to the urban and farther. The GPS unit builds exclusion zones, which will alert if an offender goes somewhere they are not allowed to be, like a radius constructed by a restraining order. Alas, Raphael Sperry, architect and director of the group Architects, Designers, and Planners for Social Responsibility, predicts that “EM will reinforce the already existing geography of urban ghettos.”12 University of California, Berkeley, sociologist Loïc Wacquant describes this geography as links between the ghetto and “hyperincarceration.”13

In Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, as in many municipalities around the country since 1983, citizens released on probation are outfitted with these EM devices. Former inmates pay a daily fee for wearing them, offloading cost to the convicted. If they fail to pay, they can be sent back to prison. If the device is tampered with or removed, that is reported, and the wearer returns to prison. Reports show that the hardship of exclusion zones and the cost of paying the fee are often enough to preclude decent and reliable employment. This construction is also built by redundant finances: EM is paid for by taxes but also by its wearers. Payments are collected by private entities in and out of the prisons and also by the local and state prison authorities with whom they partner. As has been reported, this curious logic seeks justification in prisoner reform, not through rehabilitation but rather remuneration. “Proponents of electronic monitoring hew to a doctrine of personal responsibility; they believe restitution—even to a jailer or taxpayers—is the first step toward recognizing one’s misdeeds.”14

It has to be acknowledged that wearable computing and EM are nothing new. They are part of a rich history that dates back decades, if not centuries. Steve Mann, the media artist with whom wearable computing and computational photography are practically synonymous, claims its origins as far back as the sixteenth-century abacus ring. Mann has produced countless self-portraits with his “Digital Eye Glasses” over the years. Without tracing electronic monitoring’s long history, we can establish that with the ExacuTrack® One, several new developments in the practice coalesce.

At the outer reaches of our planet’s skin, we see networks of communications infrastructure increasingly connect with tiny wearable devices, under the oceans, and in satellite networks. Google’s Project Loon now plans a vast experiment with balloons that can occupy the stratosphere twenty kilometers above the Earth’s surface, with the intention of providing broadband Internet to anywhere on the planet.15 Loon’s stated aspiration is to provide connectivity that will help to erase imbalances with poor regions of the world, a loftier goal perhaps than our mundane use of GPS devices that connect to satellites in real time for driving navigation.

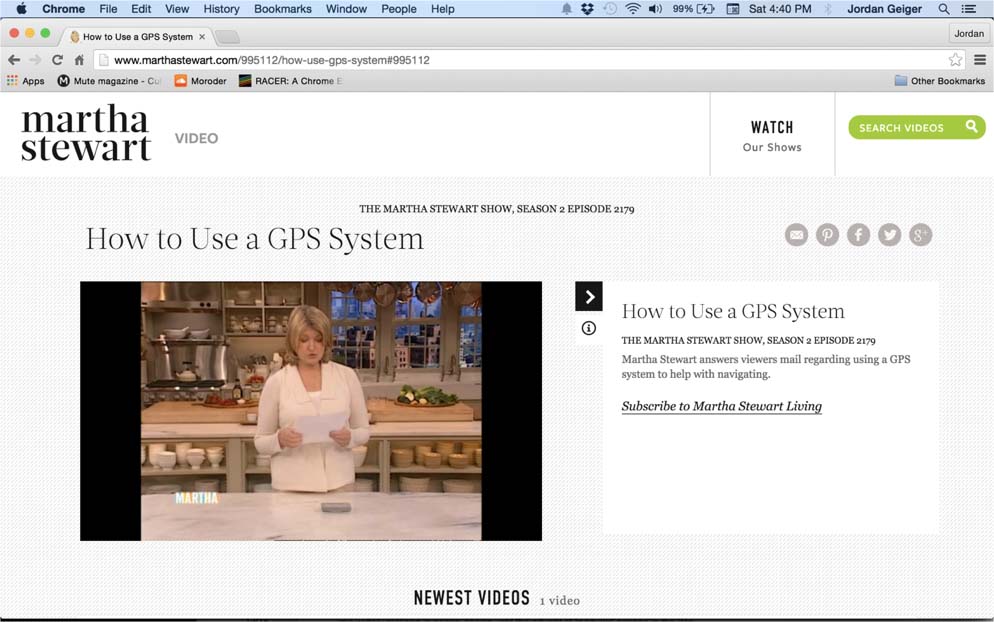

But what exactly is GPS, and how do we use it? To answer this question, one might turn, for example, to an online tutorial on Martha Stewart’s website. There is a certain cruel irony to looking at this video, where Stewart explains the GPS to her viewers, since she had just become all too familiar with the technology.16 After her conviction for insider trading of ImClone stock, Stewart was briefly incarcerated; upon being released from prison in March 2005, she had to wear an electronic anklet under house arrest. That September, she debuted her daytime TV talk show, displaying her ankle and saying: “I’m unfettered; I am free. No ankle bracelet.” Note: No images of Stewart wearing the anklet are currently locatable.

Before we simply dismiss this as a spectacle and a case of high-profile privilege, we might look to what has happened since. Just two years later, when actress Lindsay Lohan and several other celebrities were allowing themselves to be constantly photographed wearing the anklet, Karl Lagerfeld embraced the look, creating a series of ankle purses for Chanel’s 2008 collection. Widely derided as tasteless, ringed baubles for members of society’s inside circles, the gesture nonetheless indicated a withering line between stigma and status symbol in the aesthetics of the criminal citizen. Visibility moved in some cases from shame to glamour, depending variably on things like celebrity and white privilege and—probably most of all—on the ability to opt in.17

Opting in is just one key difference between EM and the escalating popularity of the quantified self movement, in which consumer products collect and then diffuse a variety of personal data. Such devices are part of a cultural shift in which we willfully expose our movements and our biometrics (our pulse, heart rate, calories burned), and our private spaces report themselves as well (thermostats, energy use, occupancy). Maps of a jog, for instance, might be hard to distinguish from the graphics of an ExacuTrack® One inclusion zone. Our calendars, our text messages, our geolocational data—this is all wrapped around our limbs and radiated across our personal networks but also liable to seep onward, to unintended eyes. Where ExacuTrack® data can often be such a deluge as to defy human processing, quantified self data is meant to be interpretable just to us and to those with whom we choose to share it. It now remains to be seen whether recent legislation permitting ISPs’ bundling and sale of personal browsing data sets off a heightened protectiveness of that data on the part of consumers.

What of new and evolving wearables, meanwhile, like the Cicret? Strapped to the user’s forearm, it projects data to the flesh and responds to one’s touch, thereby rendering the body’s surface an interface for both input and output. Under the rubric of entrepreneurship, skin is every bit the surface of inscription that it has been in incarceration. As with the cocktail of economic, spatial, and social models coalescing with the privatization of schools, postal services, and prisons, we see a mix of impulses in the quantified self’s spectacle of private data.

Gilles Deleuze described some of our situation twenty-seven years ago, as “a generalized crisis in relation to the environments of enclosure—prison, hospital, factory, school, family.”18 He characterized our shift from discipline to control societies, as one that moved from mold to modulation. Enclosures, he explained, are molds, “distinct casings” articulated in an “analogical” common language. Controls, on the other hand, are modulations: “like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other,” employing a numerical language. He elaborated modulations spatially but also temporally, economically, technologically, and otherwise—asserting that modulations are fundamentally interconnected mechanisms. “Man is no longer enclosed, but man is in debt,” he wrote, and he notes that the “electronic collar” emerged as one specific example of a resulting control mechanism.

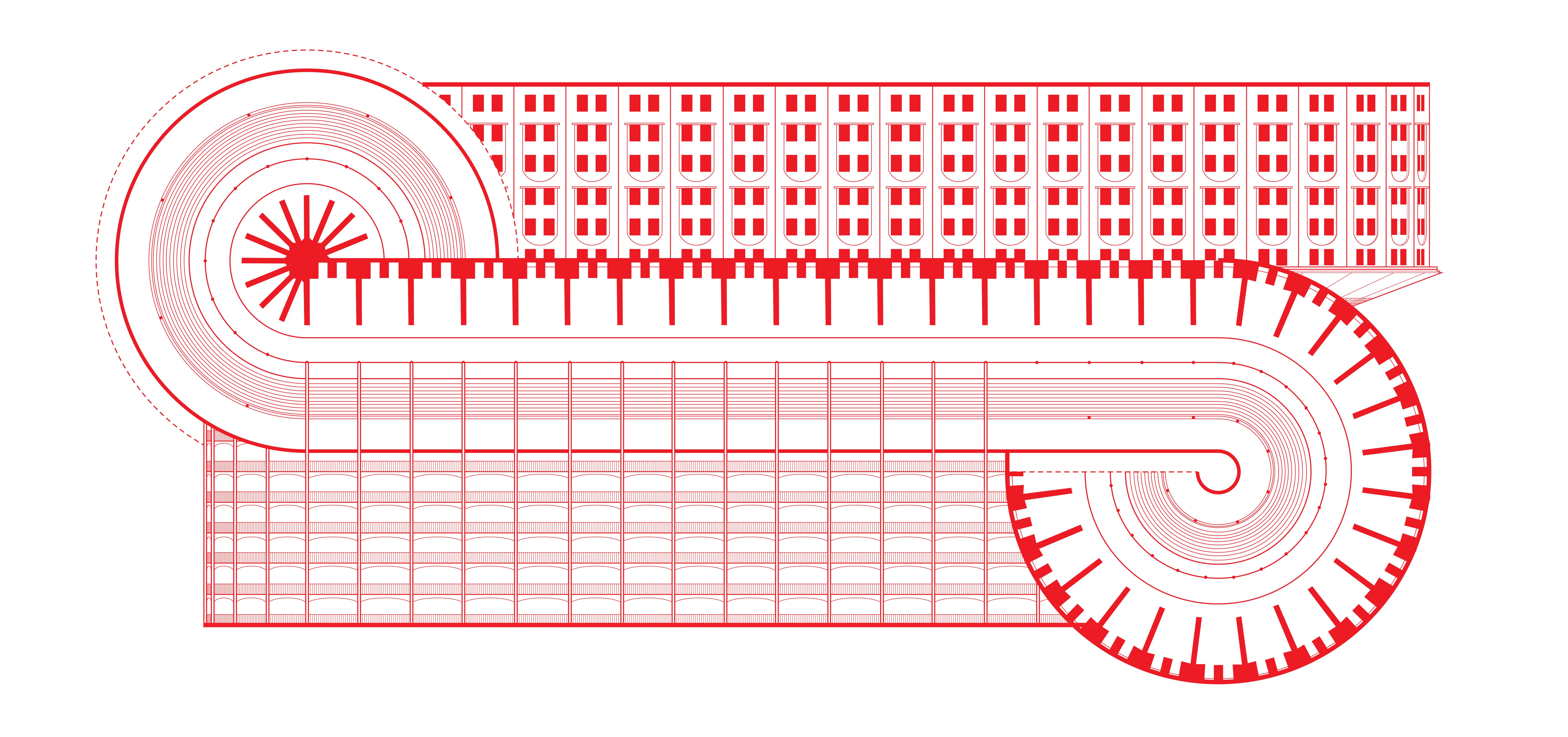

The backdrop to Deleuze’s “postscript” is Michel Foucault’s famed essay on “Panopticism,” alongside a longer history of molds, modulations, and their shifting motivations. Foucault described the masterful operation of late eighteenth-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s invention of a prison—one that relied on new technologies of gas lighting and cast iron, on the circular form of its plan, and on Bentham’s philosophy of surveillance as a basis for moral reform. It was the building’s disciplinary function that most preoccupied Foucault, a circle of cells enclosed a tower that placed the guard psychologically in the mind of every inmate at all times, since a prisoner could never know whether or not he was being watched.

Just a few years after Bentham conceived of the panopticon, the United States saw its first version of the idea take shape—a noticeably different shape with some shifted ideology—in Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary of 1829. Raphael Sperry has pointed out that the “first prisons in the independent United States were established as ‘penitentiaries’ to denote their prisoners as religious ‘penitents,’ serving time for their sins.”19 Accordingly, the radial arms of Eastern State Penitentiary provided only solitary confinement as an intended basis for reflection and rehabilitation. The building’s discipline was in its composition of redundant enclosures: cell walls, blocks, and outer walls that separated criminals from outside society and, later, the city. The penitent’s rehabilitation and return to society motivated these mechanisms, as his citizenship was not in question.

Paul Virilio has recounted how metal detectors implemented in French maximum security prisons were first deployed in airports—the same technology enabling freedom of movement finding its way to limit it.20 Not surprisingly, as technologies shift from detection to data collection, as they transfer industries in real time, as they nimbly join the scales of the body to the planet and apply equally to motion and stasis, their operations are physically condensed into a single ring around your ankle.

Today, the United States has many levels of citizenry—the supposed equality of citizens notwithstanding—watching one another, making and made by a raft of circular logics: spatial and temporal, but also legal, technological, and moral. To consider the space of the citizen convicted of a crime, and how that space is perceived or sensible, is to review the authoritative, ideological, formal, and financial redundancies that define incarceration across many scales.

As the new administration of the US government rushes more breathlessly than any before it to reduce civic agencies and services, to outsource and deregulate their privatization, and to streamline their methods of commodifying and re-commodifying the incarcerated, we reevaluate the ways that “enclosure” continues to shift under varied influences, and with contradictory impulses for penal justice.

The quantified self, economic redundancy, the outsourcing of carceral architectures into private space—are these new terms of citizenship, part of what Jacques Rancière has called the “distribution of the sensible”?21 Is this now what is meant when we say that there will be no taxation without representation? And are we now set on imprisoning ourselves in this new aesthetic? Defined as such, the sensible looks like an endless moiré pattern, concentric and overlapping circles in time and space, extending in scale from our ankle and wrist to the prison walls, the city, and onward to the stratosphere.

-

Among many accounts, this was well documented in the exhibition Thirteen Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair, Queens Museum, April 27, 2014 to September 7, 2014; and at The Andy Warhol Museum, September 27, 2014 to January 4, 2015. See Queens Museum, “Thirteen Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair,” press release, April 10, 2014, link. ↩

-

CCA, “CCA First Quarter 2008 Financial Results and Additional Construction,” press release, May 6, 2008, link. ↩

-

CCA, “CCA Expands Existing Intergovernmental Service Agreement to Manage the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas,” press release, September 24, 2014, link. ↩

-

In the Public Interest, Criminal Lockup Quota Report: How Lockup Quotas and “Low-Crime Taxes” Guarantee Profits for Private Prison Corporations (Washington, DC: In the Public Interest, 2013), link. ↩

-

Data provided by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. See map by Rose Heyer, 2005, link. ↩

-

For detailed data sourcing, see link; and graph by Peter Wagner, 2014, link. ↩

-

Vicky Peláez, “The Prison Industry in the United States: Big Business or a New Form of Slavery?” Global Research, August 28, 2016, link. ↩

-

A recent study by the Pew Charitable Trusts reports that the “number of active electronic offender-tracking devices rose nearly 140 percent” between 2005 and 2015. See the Pew Charitable Trusts, “Use of Electronic Offender-Tracking Devices Expands Sharply,” link.

GPS You Can Trust…when you need to know where an offender is, or has been (with near real time tracking)…BI ExecuTrack® One provides effective offender tracking with both time and financial advantages.[^9]

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, “Use of Electronic Offender-Tracking Devices Expands Sharply.” ↩

-

BI Incorporated, “BI Incorporated Announces BI ExacuTrack® One GPS Tracking System,” press release, July 16, 2009, link. ↩

-

Pew Charitable Trusts, “Use of Electronic Offender-Tracking Devices Expands Sharply.” ↩

-

From an email with the author, May 12, 2014. ↩

-

While no studies of EM’s distribution across demographics is readily available, Wacquant speaks to incarceration and race more generally. The “expansion and intensification of the activities of the American police, criminal courts, and prison over the past thirty years have been finely targeted, first by class, second by race, and third by place, leading not to mass incarceration but to the hyperincarceration of (sub)proletarian African American men from the imploding ghetto.” See Loïc Wacquant, “Class, Race, and Hyperincarceration in Revanchist America,” Daedalus, vol. 139, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 74–90. ↩

-

Rachel Swan, “Jail To-Go: Ankle Bracelets Could Be the Next Great Law Enforcement Tool, if the City Doesn’t Get Defeated by Data,” SF Weekly, May 21, 2014, link. ↩

-

“Balloon-Powered Internet for Everyone,” Project Loon, link. ↩

-

“How to Use a GPS System,” The Martha Stewart Show, season 2, episode 2179, 2006. ↩

-

As attested to by one recent author and inhabitant of an EM cuff: “To escape prison, I submitted to an alternative punishment that outsourced not only the housing and upkeep of the inmate but the shaming as well.” Luke Martinez, “Homeward Bound,” the New Inquiry, March 22, 2017, link. ↩

-

Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992): 3–7. ↩

-

“Prison History,” ADPSR, link. See also Raphael Sperry, “Death by Design,” theAvery Review 2 (October 2014), link. ↩

-

Paul Virilio, Lost Dimension (New York: Semiotext(e), 1983), 9–29. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, Le Partage du sensible: Esthétique et politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2000). ↩

Jordan Geiger is editor of the book Entr’acte: Performing Publics, Pervasive Media, and Architecture. His work relates architecture to new social and environmental implications of human computer interaction. Geiger is currently a member of the Center for Architecture and Situated Technologies, and assistant professor of architecture, at the University at Buffalo (SUNY).