“They’re buildings, not bombs, not missiles,” said Kayson’s lawyer.1 On January 21, 2013, an undeclared check for the equivalent of US$70 million in Venezuelan currency was found at the Düsseldorf airport in the name of the Iranian construction company. In an interview held at Kayson’s satellite office in Caracas, the company’s lawyer explained that there was nothing illegal about the check: a detailed budget was sent every month from the Caracas office to its home office in Tehran, and in turn, a check was sent back for the required amount. Since the economic sanctions prohibited shipping companies such as DHL or FedEx from delivering such parcels, there was no option left but to trust an employee or a friend to carry it.

For many years, Kayson operated as a Tehran-based private developer. Its projects were often large-scale and infrastructural, including work such as Imam International Airport, the Aliabad Gas pipeline, and Tehran’s first metro tunnels. Regardless of type, all their projects were located within the borders of Iran. But a major shift occurred in the company’s scope of work in 2006 when it signed a set of contracts for delivering a total of 20,008 housing units in Venezuela.2 Distributed across seven provinces of the Bolivarian Republic in the form of small townships, the housing would contribute to Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela (GMVV), a national housing scheme launched by Hugo Chavez.3 Less than two years later, the company signed a similar set of contracts for the building of 21,552 housing units in the two Iranian provinces of Tehran and Kermanshah.4 There, too, the houses were to contribute to a national housing reform, introduced by the corresponding president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Both projects were in the form of townships located far from the urban centers; they targeted less advantaged populations; and they had the Ministry of Housing as the client. Following these contracts, in 2013, Kayson was engaged for the construction of yet another residential township, this time near Baghdad and commissioned by the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education.5

Beginning in 2006, severe sanctions were imposed by the UN Security Council and, in turn, by the international market on Iranian companies. The building of such large quantities of houses in Venezuela, Iran, and Iraq by an Iranian developer therefore required alliances and collaborations with political intentions and effects that stretched well beyond the typical commercial boundaries of international business—which is to say that the economics of the matter were guided in part by the symbolic value of an Iranian corporation doing business abroad, secured by no small effort on the part of the Iranian state. For example, the carrier of the company check who was arrested in the Düsseldorf airport was not a Kayson employee but a former Iranian economic minister and governor of the Central Bank. At higher levels, presidents Ahmadinejad and Chavez paid regular state visits to each other’s countries and reviewed one another’s housing reforms with great enthusiasm. As early as 2007, the two leaders had declared an “axis of unity,” pledging to help those who were attempting to liberate themselves from US imperialism.6 Later in 2009, they announced the launch of a joint development bank at a “G-2” summit held in Tehran, which was countering a concurrent G-20 Summit in London.7 Over the course of these years, the two leaders exchanged various gifts, including a carpet woven with portraits of the two holding hands against the backdrop of a blue sky. The bond between the two countries, in Ahmadinejad’s words, was a deep and “brotherly tie.”8

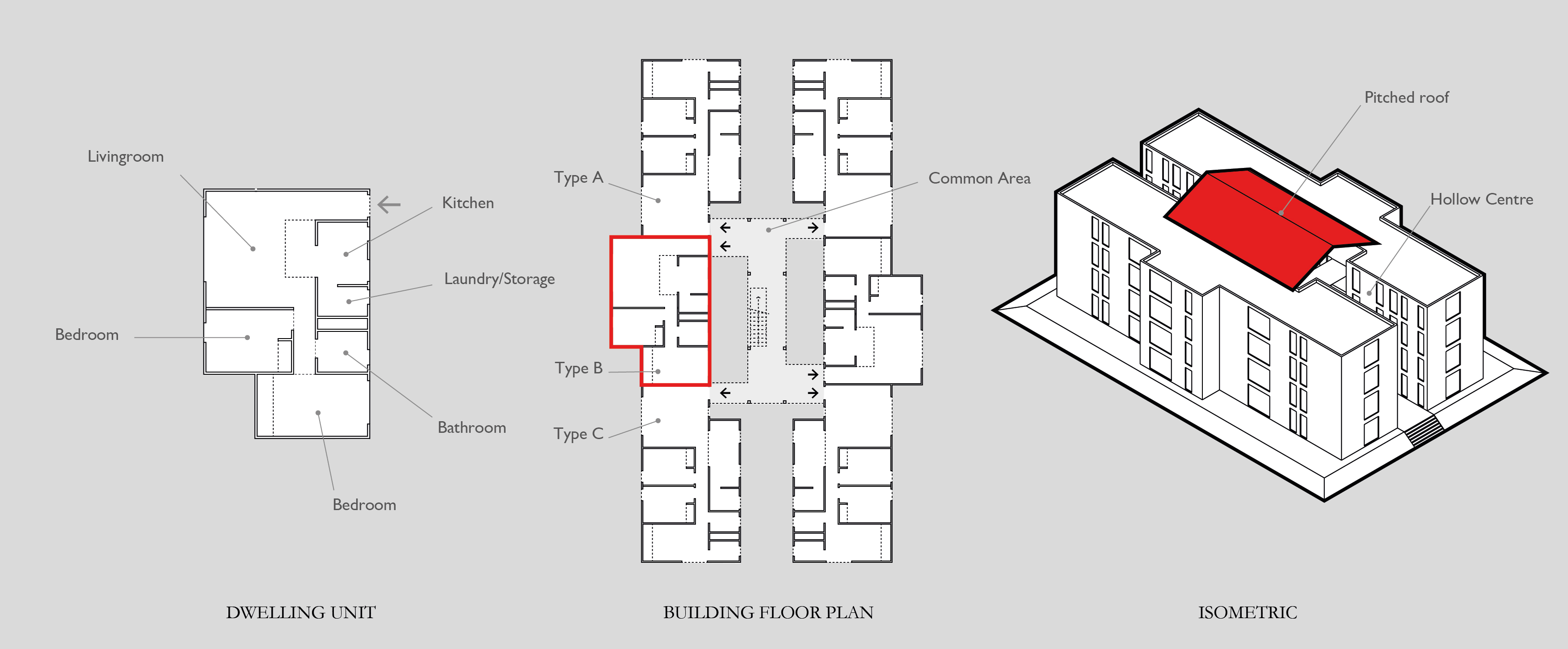

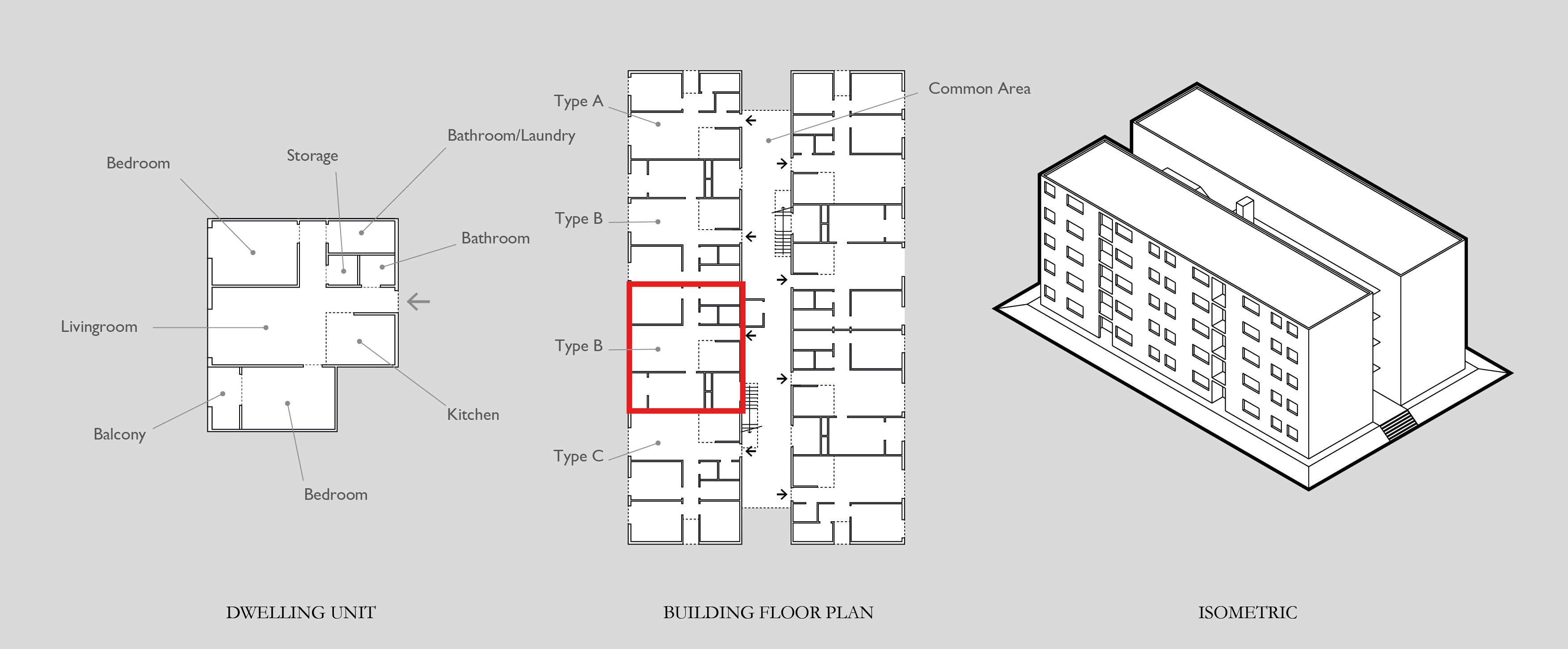

According to Kayson’s website, the company had invented a “ground-breaking” and “superior” construction system that blended techniques of prefabrication and cast in-situ concrete.9 Complex steel formworks were designed and manufactured in the factory then brought on-site to cast the required monolithic elements. With only a few formworks, a large number of modules were produced that could be repeated and rearranged in various configurations. The 16,080 units of Kayson housing in Tehran, for example, were produced with a total of sixteen wall formworks. The technique allowed for little diversity, and the buildings appeared identical from the outside. They were fit close to one another in parallel rows. Each and every building was prescribed with a height of five stories and the identical arrangement of façade openings. Each level accommodated a total of eight units mirrored on two sides of a narrow corridor, and only six types of units existed in each building.

Apart from typological limitations, the technique also imposed a set of design constraints that affected the morphology of the settlement. For example, the assembly of the formwork was performed by a particular tower crane fixed in ground with a limited field of reach. This required the buildings to be grouped in blocks of six with distances that could vary only within a narrow bandwidth.10 Another constraint was that the load-bearing walls had to be placed on the perimeters, eliminating the possibility of the ground floor serving as a space for parking or shops.11

At the expense of such design constraints, Kayson’s technology offered a record-breaking speed of construction. This speed was possible only through a particular organization of labor. An architect designed the settlement layout and its building types, and the work was then passed to a skilled engineer who would streamline the design to a few repeatable elements. The formworks of these elements were created in the factory. Both the creative design of the homes and the scientific streamlining of their building elements and the robotic manufacturing of the formworks were to take place in Kayson’s headquarters in Tehran. From that point onward, labor was organized around the construction site, whether in Iran, Iraq, or Venezuela. It was claimed that the construction method had “a rhythmical process” that transferred the skills of casting to the individual workers “through its own merit.”12 This division of labor eliminated human misunderstandings and increased the speed of construction to six hundred units per month and one residential unit per hour.13

Beyond its exceptional speed, Kayson’s technique offered a positive and dynamic image for national development. The company produced newsprints, pamphlets, and promotional videos in Farsi, Spanish, and English, reporting on its construction process. A video on the making of the ten-thousand-unit Housing Project in Venezuela, for example, begins with melancholic music and a black-and-white slide show of iconic architectural buildings under construction, including images of workers posing in front of the unfinished Golden Gate Bridge. This sequence is followed by a quick jump-cut to Venezuelan construction workers and Iranian engineers posing with victory smiles against the backdrop of a Kayson settlement. Bird’s-eye-view footage is sped up to show large-scale cranes in action, buildings rising up floor by floor, and entire towns emerging from fields and forests in mere seconds. The video concludes with a slow fade from lonely children playing among congested Venezuelan slums to happy family hugs in furnished interiors of Kayson apartments. In this narrative, the Kayson housing is rendered as the grand icon of a bright future.

The Kayson clients in Iran, Venezuela, and Iraq were governmental bodies, and all projects targeted the lower socioeconomic strata of the population. How did each government understand its people, their ways of dwelling, and their household structures? To what degree did each government wish to intervene in the daily lives of its people?

In an interview, the architect of Kayson’s dwelling units, Sam Tehranchi, explained that for two of the projects, the design was based on detailed architectural briefs provided by the corresponding clients, the Ministry of Housing in Venezuela, and the Ministry of Higher Education in Iraq.14 In the Venezuelan case, the brief explained that the new settlements were to house those who had lived in “slum” neighborhoods where little formal boundary existed between households and therefore asked that the architect pay careful attention to the construction of neighborly relations.15 Each household had to be framed as a distinct unit, and its interior and exterior had to be separated. In response, the architects proposed two C-shaped blocks of private apartments surrounding a more public volume at their center. The two blocks didn’t touch one another, and a gap was preserved, allowing breezes to pass through the central volume on warmer days. Tehranchi thought of the center as an area shared between the units where neighbors could greet one another and children could play. With this in mind, he designed the space much wider than a standard corridor, with ample voids and openings between dwellings.

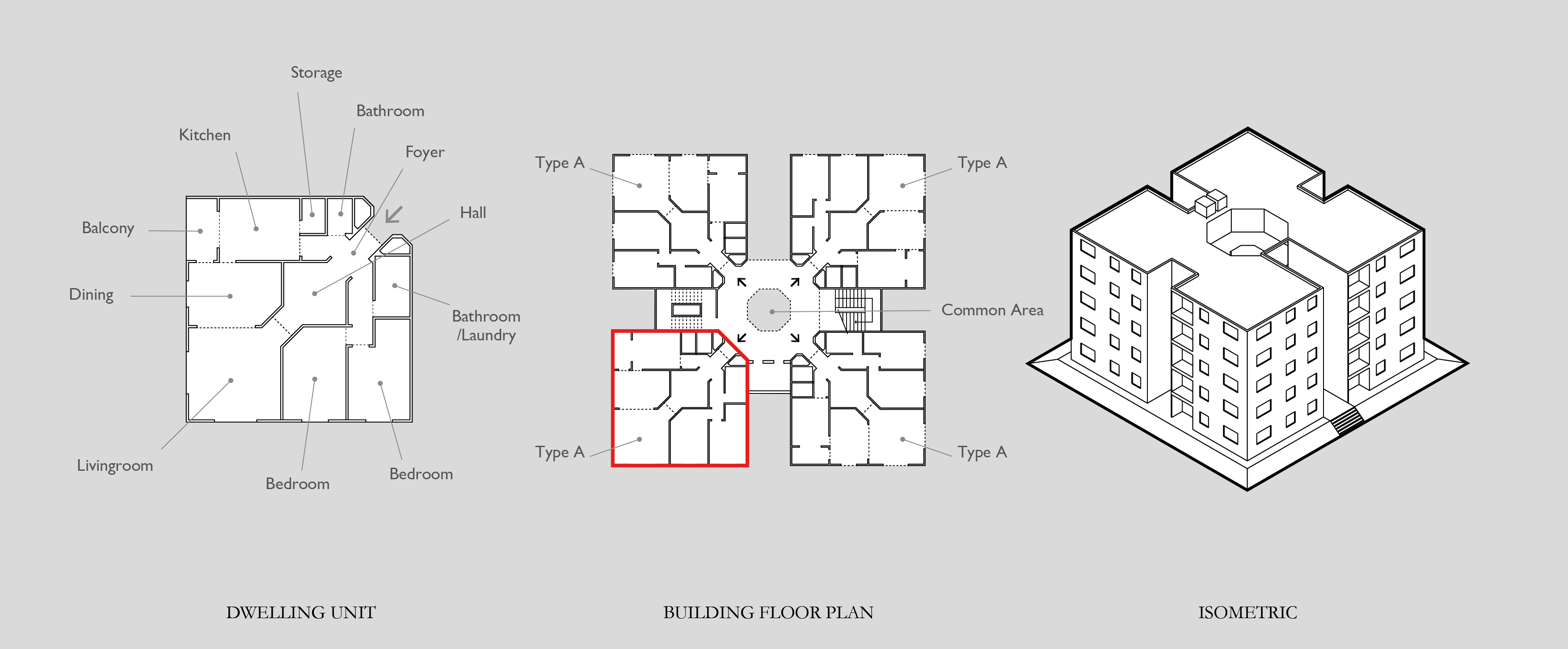

While the units in Venezuela required clear definition of exterior and interior, the case was more complex in Iraq. There, the brief explained the typical Iraqi Shia family as a contradictory unit. On one hand, its structure was loose in the sense that extended kin, distant family members, and coworkers often came for visits from faraway places and stayed for periods of up to several months. On the other hand, social relations between genders of the household were bound by the moral codes of Shi’im around Mahrams and Namahrams.16 Mingling was prohibited, and visual connections had to be negotiated. It was left to the architect to resolve the inclusion of the outsider, the Namahram, in the closed structure of the home.

In response to this problem, Tehranchi conceived his proposed housing unit as an assemblage of rooms. Each room was assigned a unique name, size, furnishing, and number of openings, which all had to be installed in a particular sequence. Accordingly, each room accommodated a unique notion of privacy. For example, the hall was designed as a perfect square and positioned perpendicular to the entrance and hence was the most accessible room to any outsider entering the unit. The living room, in contrast, was in the farthest corner of the apartment with two windows offering views to the outside. It was in close proximity to the hall and dining room but could be separated from them with movable partitions and become a fully enclosed space when required. In this arrangement, the Mahrams of the house could intimately gather in the living room secure from their outsider guest. In a similar fashion, the architect incorporated a range of rooms for collective eating. While the dining room offered a ceremonial stage for sharing a meal with outsiders, the kitchen was spacious enough to accommodate an intimate dinner table.

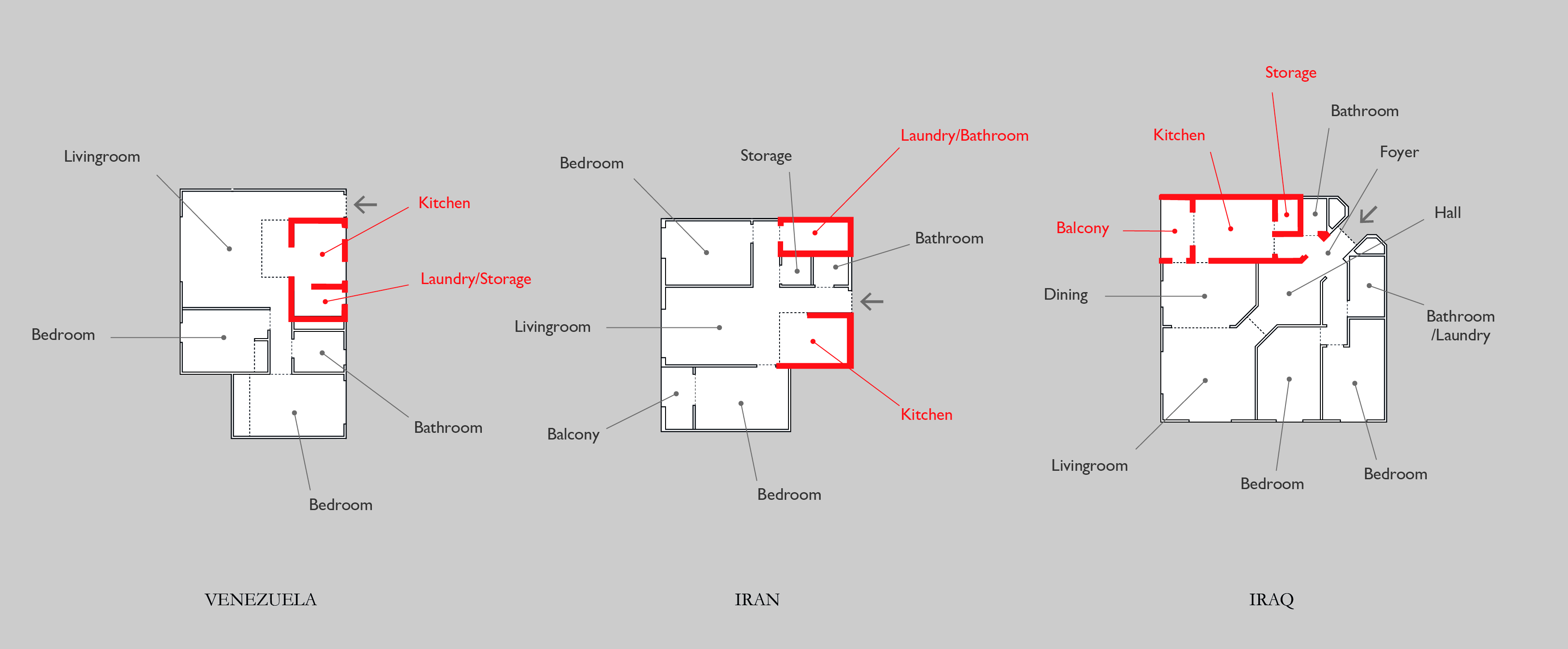

In Iraq and Venezuela, the plan was encoded with certain behaviors and gender roles. In Iraq, the floor plan was organized in such a way that the middle was reserved for controlled interaction, the rooms for the individuals were grouped on one side, and those associated with services including the kitchen, the storage space, the laundry, and the balcony (often used for outdoor cooking) were clustered on another. In order to enter the service cluster, one had to make a forty-five-degree turn away from the unit’s main axis of circulation, into a new corridor, and then negotiate his way through a set of closed doors. These spaces, and the person who was to spend most of her time within their bounds, often a mother and a wife, were fully separated from the rest of household. While this assured visual privacy and adherence to the norms of Mahram and Namahram, it also assured that this woman would have little awareness of what was happening in the rest of the unit. Her role was confined to the basic provision of a set of services.

In Venezuela, the kitchen was open to the living room yet separated from it by a slight shift off the apartment’s central axis. The laundry was fit closely to the kitchen to such an extent that to access the former, one had to pass through the latter. This arrangement separated the types of circulation that were associated with the roles of cooking and washing from the rest of the household activities. The labor of reproduction was not to alienate the individual. Standing in the kitchen, one could monitor the living room where the daily life of the household would unfold. Moreover, both kitchen and laundry had visual access to the common area outside the unit where children were likely to play. Cooking and washing were therefore inseparable from the task of policing the family and hence associated with a certain level of authority.

Domestic labor and its corresponding hierarchies were articulated differently in the Kayson houses of Iran. Here, service rooms were distributed across the organization of the floor plan with a considerable distance from one another. This order suggested that the different types of labor required for the sustenance of the household could be divided between a few individuals. Similar to Venezuela, the kitchens of the Iranian houses were designed as extensions of the living rooms. This layout soon became the target of attacks from hardliners in Farsi social media.17 They began from the assumption that cooking was a gendered role reserved for mothers and wives of the household. To abide by the laws of Shi’ism and to protect these women from the gaze of the Namahram, their place had to be separated. With this framework they argued that the private kitchen was the essence of an Islamic home and that the inclusion of openings between the kitchen and the living room threatened the Islamic order of the most elementary unit of the society.

This critique had many holes: what characterizes an Islamic order has constantly shifted throughout history depending on social and political specificities, sometimes advocating for spiritual solitude and other times for collective rebellions. The house of Prophet Muhammad himself, for example, was simply a large plot of land, enclosed by perimeter walls, including two identical rooms and a covered platform for greeting guests with no particular area reserved for cooking.18 The hardline criticism was, therefore, far from a defense of an Islamic order that has always been in place. Rather, it was an attempt to problematize a common feature of the dwelling units that were built under Ahmadinejad as part of his national housing plan and, in turn, associated with the entirety of his project of governance.

Gathering from the architect’s stories, and unlike with the cases of Iraq and Venezuela, no architectural brief was composed for the Iranian houses, and instructions were communicated in an informal manner. In the case of a site inspection in Parand, for example, a state engineer had advised for designing open kitchens instead of closed ones on the grounds that it would reduce wall space and could eventually allow more people to be housed.19 The lack of an official brief signified that the beneficiaries of the houses were never understood, studied, or valued by the Iranian state as members of a working class with certain social rights. In Ahmadinejad’s reform, the house was to act as the compassionate gift of a caring state. It was a gift and a tie that brought obligations with it: to receive and to reciprocate. Those who received the gift and became homeowners thought of themselves as an emerging middle class and felt indebted to the patronage of the state for their new status. To reciprocate this gift, they were willing to be orchestrated in public forums and show their support in government rallies in masses.20 Each additional housing unit counted for the state as a few extra ties of compassion.

Each Kayson building in Iran accommodated a total of forty households throughout its five stories.21 No meetings were held between the representatives of Kayson and those who had applied to its houses. “I wanted to differentiate the residents from one another,” explained the architect. “We wanted to give them a sense of ownership…and individuality. So we proposed a new façade system. In our system we had a color gradient for the buildings… The vision was to create a sense of harmony.”22 The pastel colors were to distinguish the buildings from one another, introducing harmonious differences to the lives of a people who were otherwise considered to be homogenous. This approach in the houses of Iran contrasted with the Iraqi project in which the façade system was identical. In Venezuela, too, the façades of the Kayson buildings were uniform. But there, they were decorated with red roofs, mimicking the aesthetics of the reform brought by Chavez and thereby signifying the residents as supporters of the Venezuelan president. The buildings therefore communicated a sense of political unity. The harmonious pastel façades in Iran contrasted with the red roofs of Venezuela in that they avoided signifying the project of Ahmadinejad altogether. In so being, they tended to ease the resident out of their burden of patronage.

In Iran, Venezuela, and Iraq, Kayson housing was part of an apparatus—a heterogeneous ensemble of architectural briefs, construction techniques, design decisions, moral propositions, governmental agendas, and extra-state regimes of power.23 In these houses, the color of the façades, the position of the rooms, and the arrangement of the openings, were influenced by the relations between a transnational set of actors and institutions. Therefore, once complete and occupied, the houses entangled the daily lives of their inhabitants with an apparatus that operated at the scale of the globe. A family meal in the open kitchen of a Kayson house in Iran and the habits around its preparation and service are contingent not just on locally articulated religious and cultural practices but also on an architect’s conception of gender roles and class identities, a president’s populist policies, an anti-imperialist tie of brotherhood between two statesmen, the sanctions of a United Nation’s Security Council, and the murky business of a private developer.

The dynamic status of such an apparatus cannot be overlooked. In moving to their new homes, the dwellers, consciously or not, became participants in this field of forces. If the architecture of the homes they were given was sharpened to secure certain behaviors and gender roles, its disruption was in itself a practice of power and an act of resistance. The most minute interventions, then—rearranging the furniture, adding a curtain, removing an internal wall, placing plants in the shared spaces of their apartments—would inevitably affect relations of power at other scales. The apparatus within which the houses of Kayson were installed has always been contingent on the behavior of their dwellers, their daily life, their habits, and their rituals, perhaps even more so today as the governances of Ahmadinejad and Chavez have come to their ends.

-

For full account of the event, see William Neuman, “Firm Denies Deception in Big Check Tied to Iran,” the New York Times, February 5, 2015, link. ↩

-

“10,000-Unit Housing Project, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,” Kayson INC., link. ↩

-

For thorough analysis of Misión Vivienda in relation to Chavez’s social and territorial reforms in Venezuela, see Godofredo Pereira, “Underground: Venezuela’s Territorial Fetishism,” in Savage Objects (Guimaraes: Leya Publishers, 2012), 233–248. ↩

-

“Parand New City 16,080-Unit Housing Project,” Kayson INC., link; “Kermanshah 4,920-Unit Housing Project,” Kayson INC., link. ↩

-

Parisa Hafezi, “Iran, Venezuela in ‘Axis of Unity’ against U.S.,” Reuters, July 2, 2007, link. ↩

-

Nasser Karimi, “Venezuelan Leader: ‘Capitalism Needs to Go Down,’” San Diego Union-Tribune, April 3, 2009, link. ↩

-

“Iran and Venezuela deepen ‘Strategic Alliance,’” BBC, October 21, 2010, link. ↩

-

Kayson Engineer, personal interview with the author, September 9, 2014. ↩

-

Sam Tehranchi, Skype interview with the author, September 30 and October 3, 2016. ↩

-

“The 10,000-Unit Housing Project,” promotional video, Kayson INC., link. ↩

-

“10,000-Unit Housing Project, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,” link. ↩

-

Interview with Sam Tehranchi. ↩

-

The interview with the architect was conducted in Farsi. In describing the brief he had received for the project in Venezuela and its definition of those who were to be housed, he used the word Zagheh Neshin [نشین زاغه]. This word translates to English as “slum dwellers.” ↩

-

Mahram refers to people of the same sex or those who are close family members, for example, members of a nuclear family and mothers/fathers-in-law. Namahram is the opposite of Mahram and refers to someone of an opposite sex who is not a close family member. According to Islam, certain interactions are prohibited between the Namahrams. For example, they are not allowed to shake hands or have physical contact. Another example is that women have to wear the hijab in the presence of a Namahram. ↩

-

For example, see “Javadi Amoli: Open Kitchen Is Not Islamic,” Mashregh News, May 27, 2011, link. ↩

-

K.A.C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1969). ↩

-

Interview with Sam Tehranchi. ↩

-

Samaneh Moafi, “Crafting a New Middle Class,” the Real Review 2 (autumn 2016). ↩

-

Interview with Sam Tehranchi. ↩

-

Interview with Sam Tehranchi. ↩

-

See Michel Foucault, “The Confession of the Flesh,” in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 194–196. ↩

Samaneh Moafi is an architect and researcher. She is a PhD candidate at the Architectural Association and a research fellow in forensic architecture.