October 18, 2018. New York City. Frank Gehry: Building Justice will meet its first public audience at the Chelsea Cinépolis. Co-presented by New York Magazine. A conversation with the director to follow.

A film crew follows Frank Gehry and company as he embraces a late-career assignment. His brief has come by way of the Open Society Foundations, and given Gehry’s reknown for swooping halls of culture, it’s one that might surprise: the redesign of the American prison. Rather than apply his own brand of imagination to a carceral project in his office, Gehry turns to his design studios at SCI-Arc and Yale—commissioning the documentary Frank Gehry: Building Justice to chronicle the whole thing.1 Abandoning the concert hall for the prison, the 89-year-old architect asks how architectural academia might lend imagination to the intractable problem of mass incarceration by reconceiving its physical infrastructure. As the central concern of the documentary, it also extends the question to a slightly larger architectural public. However, Gehry doesn’t so much ask this than appear as the gravitational force around which the future of the prison might cohere. The production of the documentary is an integral part of the studio it documents, orchestrating the circle of collaborators and experts that supported its necessarily in-depth research. Gehry set the film project in motion around the time he first pitched the studio at SCI-Arc, which debuted in the spring of 2017. There was no budget for a production, but he was quick to enlist a trusted filmmaker to ensure there was a record of his efforts: Ultan Guilfoyle, who had worked on Sketches of Frank Gehry, Sydney Pollack’s portrait of Gehry’s American Mastery for PBS. You “can’t say no to Frank Gehry,” Guilfoyle recalled of the pitch—promptly agreeing to direct the feature even without a working budget. “You figure it out.”2

“A super important film, a design film, a human film.”3

As the organizer of the Architecture and Design Film Festival introduces it, the documentary is itself important work. Those of us assembled for its world premiere at the Chelsea Cinépolis are ready to have a feel-good night. By watching, we have entered into the social contract of the documentary: we share in the concern for its premise; we ratify its content; we absorb and presumably circulate all the cultural correction it attempts by way of having been seen. It is a part of a media mechanism that does not just bear witness but, as “a design film,” serves the positivist project of solution. Our consumption embodies, in reclining seats, liberalism’s preference for benevolent politics-as-entertainment à la NowThis; not quite the critical edification that inspires wokeness, as with Ava Duvernay’s 13th but the much sweeter medicine of having considered, if only for seventy minutes, the human consequence of design. Someone (our most famous architect!) is finally thinking about mass incarceration, see?

There is indeed some truth-telling to be done about the status of incarceration in this country. And the film assembles a supporting cast who is perhaps best equipped to speak to the issue: Alex Busansky of Impact Justice and Susan Burton of New Way of Life, a Compton-based re-entry program, are brought on as collaborating educators to guide the project as its students, and now its audience, confront a demonstrably unjust system of custody and the conditions of life that it generates. Anticipating an audience that mirrors the makeup of the architecture profession, these are revelations to be made by a privileged white public not already keenly aware of the threat or burden of lockup, the experience of catching the Q100 from Queens Plaza to Rikers, waiting in a line supervised by corrections officers and withstanding their invasive searches, all in order to visit someone you love, someone who may not yet have been found guilty of a crime.4 As with the expulsion of detention onto the East River, the reality of corrections (and pre-conviction custody) is a thing that actively holds itself from view, which in turn cultivates the desire for MSNBC Lockup–style windows into far-away cells.5 As an object of a particular gaze or ignorance, the state of American carcerality is confronted by the designers of Building Justice as a system that has grown independently from a naturalized set of circumstances—the perhaps cumulative but not conspiratorial operations of policy, policing, and sentencing that fill jails and prisons disproportionately with black and brown “offenders.” Designers, woke and otherwise, can agree the issue is complex but somehow see it as extricable from the domain of architectural invention. The building of detention and correctional facilities away from residential areas, on islands and up rivers, situates confinement as something removed from daily life—and thus something that can be maintained through the ignorance of otherwise well-intentioned citizen-designers. With the exception of a dedicated few practitioners, architects absolve themselves of responsibility to incarceration as an infrastructure that is built without their participation and congratulate themselves when considering it anew as an object of their critical attention.6 Surely, we can apply ourselves to more human solutions than solitary confinement. But no one really knows to care until they are made to breathe the stale air of the cell; the film has to convince us first. That we are not really aware of the material realities of mass incarceration—its narrow hallways, low-lit cells, and the SHU—is a convenient premise for its belated address. Or as Frank Gehry insists, “what if people change their ways and start treating people like human beings? What would it be like? What would prisons look like?”

But before we get into all of that, the feature is preceded with a short film about a facility for survivors of child abuse, the third-place finisher in the AIA’s 2018 Film Challenge. ChildSafe: Designed to Heal is a film and project by Overland Partners, which follows their intervention in another institutional form (in this case, something like Child Protective Services) in urgent need of the special touch of Good Design. In the way that “humanity” drives Gehry’s project, “hope” is the conceptual frame for Overland Partners’ “sheltering roofline,” “healing garden,” and other therapeutic strategies prioritizing the “experience of the child” while also providing for the security of the facility, the sequestering of evidence, and the processing of abusers.7 By locating opportunities to soften the sharp edges of legal procedure, the designers attest to the role that a building might play in the larger social infrastructure of child protection and the prosecution of abuse cases across agencies. Even the CEO of ChildSafe speculates in the documentary that “maybe in 20 years, we can put the building up for sale,” for it will have fully solved the problems for which it was built. Building for the end of a grim but necessary measure of governance opens up a possibility of abolition—but only through a life cycle of rehabilitation that mirrors the duration of a building designed with its hopeful obsolescence in mind. ChildSafe: Designed to Heal delivers an instrumental claim shared by the film we are about to see: that thoughtful architectural intervention can remedy the problems that buildings otherwise maintain. Bad design of the prison contributes to recidivism, not rehabilitation—good design, on the other hand, can save us.

While Impact Justice, which plays a supporting role in Frank Gehry’s project, sets as its goal the eventual end of the prison system, Building Justice—or rather, Ultan Guilfoyle’s Frank Gehry: Building Justice—does not entertain abolition. Nor does it consider the project of refusal, insisted on by Raphael Sperry and the Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), an appropriate reaction. “I made the case for restorative justice,” Gehry professes.

The documentary unfolds as an explanation of why the experience of mass incarceration is bad and in need of redesign. After all, prisons are buildings. And a program of restorative justice squares neatly with an architecture that cannot be wholly undone or opposed but rehabilitated.8 Gehry’s prison studios are oriented toward a future in which people are still imprisoned but where the progress of other reforms (and a general shift in the cultural perception of incarceration) has enabled the building and financing of nonpunitive models of custody. The documentary’s interviewed characters, which include experts like James Forman Jr., who teaches at Yale’s School of Law, provide voice-overs for animations that render the prison as dark, dank, and unforgiving. Stock clips of cells confirm the contours of an architecture we have seen many times over on television.9 In lieu of primary footage, we see archival cartoons of the jail, Donald Duck pulling on elastic bars, b-roll from a carceral imaginary that can be procured from Getty Image’s extensive catalog of prison stock footage, or some nostalgic night spent in the slammer.10 The film conjures the prison not quite as it is but as an idea of a brick-and-mortar inhumanity we are already inured by.

“Nobody needs me to design a prison.”

Frank Gehry was approached by the Open Society Foundations to rethink the prison because “he has always been a humanist”—an identity earned perhaps by his own repetition but nonetheless echoed by his would-be protégés.11 By this description, Gehry is rendered an orchestrator of beautiful human experience, the kind that only architecture with real feeling for its occupants has the capacity to inspire. The Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles is held up as evidence of this power, having ennobled an otherwise unwalkable city block.12 His sensitive and charismatic expression, solicited now for the incarcerated rather than for culture, is finally being put to work. These are objectively nobler ends than any Bilbao Effect, something to top off the carp-filled bathtub of his legacy. 13

Frank Gehry has not, yet, been asked to design a prison, and so he has no signature ready to scrawl on the type. However, contributing to a 1983 exhibition at Leo Castelli’s SoHo gallery, Follies: Architecture for the Late Twentieth Century, he presented a folly named “The Prison”: a zoological scheme for a private estate that included a pavilion in the shape of—you might have already assumed—a fish.14 He’s made fish-shaped restaurants, public artworks, and lamps, but his go-to Piscean figure was unsuitable for the penitent. Rather, the prison in this proposal, set apart in the landscape from the glassy structure of the fish, was imaged as a snake in brick, coiled in a Philip Johnson–like play of opposites, as expressions of freedom and confinement.15

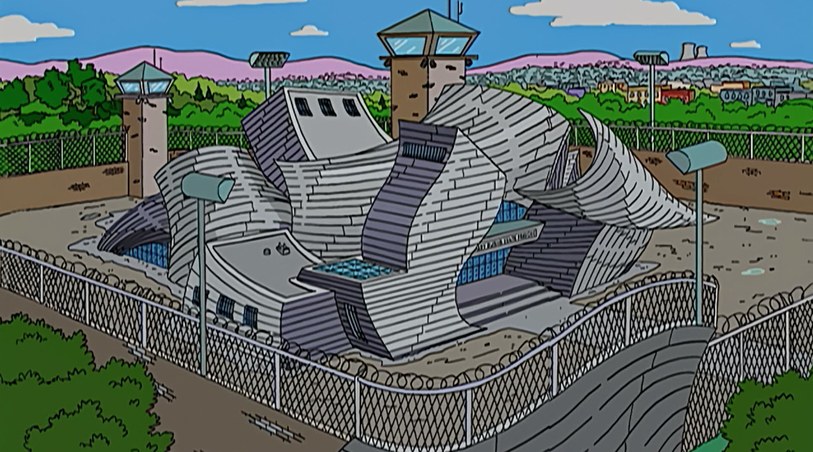

More than a decade later, after the cultural moment of Bilbao had set in, he lent his voice and image to a particularly canny episode of The Simpsons. In it, the cartoon Gehry receives an earnest request from Marge (on Snoopy stationery) to design a concert hall for the town of Springfield. Immediately uninterested, he crumples the letter—as Gehry is wont to do in the mythology of his design process—but finds the result so inspiring that he is moved to realize his own gestural creation. Mrs. Simpson will get her architecture: a superstructural grid that is bent into shape by a chorus of wrecking balls. In the third act, the building falls into disuse as Springfield residents prove unmoved by the high culture of a concert hall and is subsequently reopened as a prison. It’s a strange reversal of the redesign we find him pushing for in this 2018 work of nonfiction, where he voices architecture’s potential to rehabilitate. Gehry has since expressed regret for his participation in the episode, not because of the prison punch line but because it cemented the misunderstanding of his creative practice as Pollock-like—an action-painting style of modeling that produces something to be constructed by more expert builders.16 Given his apparent comfort with the prison as cartoon or folly, you might see how the idea of the prison has loomed larger in Gehry’s imagination than the reality of him ever designing one.

As the ostensible subject of the doc, Frank Gehry is redefined as a builder of justice by the colon that separates him from a more desirable legacy. But Gehry is not going to build a prison: “You don’t need me to design a prison. Nobody’s going to build a prison I design. We need to get a curriculum. We need to get architects thinking in different ways.” This line is repeated in the film and in the press that surrounds it. Its particular fatalism—that he would neither be offered a commission to design a prison nor sacrifice his form-making to the state or federal budgets realizing new carceral architecture—is what drives the project into pedagogy. And so Gehry defers the work of design to another generation of practitioners with the hope that the discourse, if not the practice, of social justice design outlives him in the academy. SCI-Arc and Yale, the institutions where he teaches, inevitably serve as better venues than his own office to assemble the resources and the expertise owed to a project of such complexity. Still, he is careful to assume too much responsibility: “I wasn’t sure what we were going to get out of it.”

“Usually we do concert halls.”

In 2017, a decade after Springfield exchanged its Gehry masterpiece for the prison, Gehry’s studio at Yale also dispensed with its usual subject of the concert hall.17 Deborah Berke, interviewed in the office she had inherited from Dean Robert A. M. Stern, was a willing facilitator of Gehry’s ambitious change of course:18 “Frank’s proposed project about the redesign of the American prison actually was about real life sustainability in the broadest sense; it was about urban conditions that architects could help address; it was about working with other schools on campus and bringing in their expertise; and it really was expanding the exposure of what architecture students do to connect them with a broader world.”19 In this interpretation of the studio, it’s unclear why it took Gehry of all architects to suggest the idea (or why he is best equipped to tackle it in the first place). Nonetheless, Gehry and his co-instructor Trattie Davies ask their students to consider new typological guises for the prison in a future where incarcerated populations have already decreased. The Yale students are charged with developing concepts for a nearby site, the Cheshire County Correctional Facility, for three hundred men who would otherwise be assigned to a maximum security facility.

From the first sentences that frame the course, its subject is positioned against more familiar typologies. The course description opens with an accessible statistic: that the country’s five thousand jails and correctional facilities outnumber the stock of American colleges and universities.20 With the underfunding of public schools and the overfunding and construction of new carceral institutions—imbricated systems of socialization or, in other words, the “school-to-prison pipeline”—students are moved to understand that the spaces for their education are exceeded by all those for confinement. There is a real concern, conveyed in the studio brief, for casting a relationship between the students of the university and the inmates of Cheshire County, as both subjects of disciplinary institutions.

“I generally came into the studio with the knowledge that there was a serious problem with incarceration in this country,” says one student, Matthew Kabala, who, admittedly, would have taken The Gehry Studio regardless of its topic. In the edited version of his semester-long education, Kabala’s experience is neatly spliced together with the accounts of those he is invited to learn from. Formerly incarcerated black women convened by collaborator Susan Burton testify to their experiences inside overcrowded and underventilated cells, where they were unable to receive visits from their children, and where they sustained long-term physical effects from insufficient care. Kabala cuts in to reflect, “It’s always good to put a face on a number, an issue, a statistic. And I think because I don’t know anyone personally, anyone close to me, or in my family [who] has been to prison, it’s very easy to kind of otherize the incarcerated population.” Humanity has to be learned.

Gehry is also there to learn. He rarely remarks on what is encountered by way of the research or makes references to penologies past—or at least the audience isn’t privy to those bits of teaching. The documentary largely relies on sound bites from consulting guests, replaying a studio dynamic in which Gehry is not the figural master he typically portrays but a paternal presence that authorizes the care of his “kids,” as he refers to them. He is Frank to everyone around him (including to us, as part of the documentary audience, and now to you, reading this review). He extends affirmation to a “young lady” in his SCI-Arc studio whose prison scheme has elicited the beginnings of her own signature language. “These are awkward little expressions...where she’s just taken the chance!” He is supportive of their design efforts and, maybe, more importantly, their feeling for the subject matter. Trattie Davies, Frank’s longtime co-instructor and former architect at Gehry Partners, recognizes the emotional labor foisted on the students at Yale. Of course, they had “conflicted feelings about” the prison, but the studio presented them with “inherent conflicts” that “when you get into it,” need to be resolved in their respective designs. “Inevitably, the students are asked to express their own feelings in the form of gestures and find a language that’s personal and their own,” Frank says.21 And with their feelings, they booleaned confinement and care into schemes that ultimately bore little resemblance to the familiar typology. “Bravo for trying,” he applauds.

“The Prison of the Future”

All this futurity is given over to a relatively small number of students. In lieu of time traveling, they go to Scandinavia, where the best prisons are. In Norway and Finland, prison architecture mirrors the nonpunitive culture of incarceration. The scent of baked goods drifts from secure hallways into wide-open cell doors, and corrections staff and inmates exchange friendly greetings.22 It is an eye-opening experience for the tourists of the prison. The students’ incredulity is eventually tempered as they learn about all the other circumstances that determine the quality of the carceral environment. Unlike in the United States, where a corrections industry profits from the internment of millions of people, the expense of humane custody is covered by an existing tax and policy infrastructure oriented toward re-entry, not prolonged sentences.23 This is the future that shapes and limits the imagination of Building Justice: a far-sighted utopia in which a dramatically smaller incarcerated population is housed, with minimal recidivism and only the necessary separation of serious, violent offenders. But the ability to vision an alternative to the prison as we know it is, in Alex Busanky’s mind, key to other policy shifts that might manifest this future.24 And so we are caught in a monumental loop of criminal justice reform in which any small action can be understood as an admirable step toward a better system. There is a case to be made for incremental change, but those moves are more compelling when they are aimed at policy. The rhetorical project to adjust the perception of prison, as architecture, will always be constrained to its audience.

The documentary culminates as the studio does, with the final review of design projects, which unlike other studios, was covered in The New Yorker. “As students laid out their cardboard models for inspection and pinned up their master plans, it was clear that most had ignored the part about ‘men convicted of serious, primarily violent offenses,’” Bill Keller writes in his review of the review, cross-published in The Marshall Project—the implication being that the custody of violent offenders is incompatible with the programs represented in the final schemes.25 Proposals took on the semblances of other architectural types: college campuses, residential complexes for family housing, wellness facilities, a monastery, a textile workshop with an orchard. Their denial of the prison is meant to be received as critique. It looks like an apartment complex, and we’re calling it housing. Student Jolanda Devalle defends a changing lexicon of incarceration in her response to Keller’s piece—a defense that circles back to the thesis of the film: that what needs to occur first is a shift in our understanding of the prison.

It’s an argument not easily dismissed, especially in a political moment in which the “criminal alien” is invoked to effectively authorize the federal custody of undocumented immigrants—those found guilty of often minor offenses.26

As with many juries at elite schools, the number of critics overwhelm the number of students presenting. In this case, the critics are not just so-and-so architects, celebrities in the way that Frank is, but the project’s collaborators at Impact Justice, New Way of Life, and the Open Society Foundations as well as Dwayne Reginald Betts, a poet and academic in the law school—folks who are not just in a better position to evaluate the schemes but who are also more desperate to see the system changing, in all the ways they had not yet imagined. Of the review, Deborah Berke remarks that she was most impressed not by any one project but by Susan Burton and Dwanye Betts, the two people of color who were invited to share their expertise as well as their firsthand experience of incarceration. What we see, then, are students and their instructor moved by the possibility of the Good Prison, but even well-intentioned attempts have to satisfy the intellectual investment of their collaborators and visiting critics to the studio—or at the very least avoid making a vanity project of the work already done by more experienced activists, abolitionists, and researchers.

Who is meant to be convinced at the end of this exercise is not altogether clear, because a solution was never going to be its outcome. Still, the studio relies on the belief—on behalf of the students, the formerly incarcerated, and those doing the slow work of policy and the hands-on activism—that there are indeed prospects for transformation. The “prison as apartment complex” could have a future, but in the seventy-minute runtime, the proposal is tied up with a bow as Important Work in itself. While the suggestion is meant to signal possibility, it arrives at the end of a film that was never concerned about designing a working model for prison reform, only recognizing Frank and his students for having cultivated hope for it. Susan Burton, arguably the real star of the film, is given the last word at the review. It’s less congratulatory than it is prescriptive: “You have to change the world.”

“Bravo for Trying”

Whether we see this as a world-changing project or one that documents it as such, we have to consider the entertainment value of Building Justice. Confronting the humanity of the inmate as design inspiration is one thing, but how that is packaged as a story for serious or casual viewing is another. The “prison doc,” especially one that intends to correct a cultural injustice—the blind eye we turn to the prison, or the peep show at its TV versions in Oz and Wentworth and Prison Wives—participates in a media schema that fetishizes the “inside” to the delight or enlightenment of those on the outside. The film has, so far, only been screened at Kyle Bergman’s Architecture and Design Film Festival. Both its presumed design public and a general viewership are invited in this case to consider incarceration anew. As Bjarke Ingels takes up real estate on our feed of Netflix Originals, it’s not hard to imagine this film appearing there under Gehry’s name, leading you not to Wacky Homes of the Wealthy or whatever, but suggested titles like Girls Incarcerated, the scripted Orange Is the New Black, and other streaming windows onto the criminal justice system. Girls Incarcerated, which makes compelling characters of several teenage girls at Madison Juvenile Correctional Facility in Wisconsin, was produced by the same company that made Tiny House Hunting, a show that entertains both the moral question of small-imprint living and the desire for a Magnolia Home–style renovation of an excessive lifestyle.27 The shared audience of nominally eco-design TV and reality detention drama exists along this spectrum of appreciation—for what is in need of attention and what is absorbing for other reasons.

As earnestly as it attempts to take on the urgency of mass incarceration, Frank Gehry: Building Justice is a project shaped by celebrity. It invites audiences to indulge in the architect’s newfound concern for prison reform, amplifying the fandom of its titular figure. Before the film is over, Deborah Berke nominates the work as a piece of Frank’s legacy, as something he alone is responsible for setting in motion. Building Justice is indeed a project of a corrected imagination, as the studio sets out to be: It fantasizes the prison that might be, and it portrays Frank Gehry as a protagonist in that project of reform. But it also adjusts the echo chamber of Yale School of Architecture as a place where these considerations ought to be made.28 A course on restorative justice will now be required, director Ultan Guilfoyle is happy to report.29 No longer the subject of the Gehry show, the prison is set up to be remade again and again in the academy. The pilot goes to series.

-

The Future of the Prison studio was announced to the press on a SCI-Arc Instagram post, which, per the description and “eavesdrop” reporting by the Architect’s Newspaper, “calls on emerging architects to break free of current conventions and re-imagine what we now refer to as ‘prison’ for a new era.” “Frank Gehry to Teach ‘The Future of Prison’ Course at SCI-Arc,” Architect’s Newspaper, March 28, 2017, link. ↩

-

The director, Ultan Guilfoyle in the Q&A following the screening of Frank Gehry: Building Justice (2018) at the Architecture and Design Film Festival (ADFF), October 18, 2018. ↩

-

From Kyle Bergman’s introduction to Frank Gehry: Building Justice at ADFF. ↩

-

See NYC Jails Action Coalition, “It Makes Me Want to Cry”: Visiting Rikers Island, January 2018, link. ↩

-

MSNBC Lockup, canceled in 2017, was one of the longest running reality television shows. Twenty-five seasons aired over sixteen years. In its wake, new (“kinder, gentler”) forms of prison reality media have been introduced, including WETV’s Love After Lockup and Lifetime’s Prison Wives Club. Robert Ito, “Prison Romances, Standing the Test of (Hard) Time and Cameras,” the New York Times, November 30, 2018, link. ↩

-

Rafael Sperry has been, perhaps, the most vocal critic of the prison as an object of design, calling on architects to, at the very least, refuse to design spaces for solitary confinement. The architect Joe Day, who appears in the documentary as a critic at the SCI-Arc review, has written previously on the convergence of the carceral institution with the art institution in Corrections and Collections: Architectures for Art and Crime. Jordan Geiger has discussed the current fashion of electronic monitoring for this very journal and the export of carceral architecture to private space. And Avery Review editor Jordan Carver has assembled a view onto black-site prisons in his recent book Spaces of Disappearance: The Architecture of Extraordinary Rendition. ↩

-

From the description on ChildSafe’s website: “The team kept hope at the forefront of the design process from floor to ceiling. Child-scale views to the outdoors, a sheltering roofline, and a healing garden prioritize the experience of the child. The therapeutic spaces will feel safe, but not militarized. The biological idea of prospect and refuge gives the children a sense of power in their environment, the ability to be safe and to see a brighter future beyond the walls. The primary design challenge of the facility resulted from the competing protocols. Child Protective Services and San Antonio Police Department must follow strict guidelines to ensure that no case is stymied by a technical error, and that families are indeed safe. Law enforcement, families, victims, and even self-surrendering perpetrators to enter, exit, and occupy the building in discreet and secure ways. While connectivity is essential in some parts of the building, others need to be sequestered. Parking lots, entrances, and passageways were carefully aligned so that victims would never be confronted with an unexpected encounter with their abuser.” Overland Partners, “ChildSafe,” link. ↩

-

“Justice Architecture,” is now a specialization among a number of US purveyors, usually AEC mega-firms. AECOM, HOK (including their compassionate corrections project in Redwood City), Dewberry, DLR, RicciGreene, and HDR list projects under the banner of justice, civic, corrections, or government—euphemisms for carceral projects, or categories that link them to more esteemed architectures like courthouses, city halls, re-entry facilities, etc. ↩

-

In the Q&A, Ultan Guilfolye admits the challenges of doing a film project on the American prison. He was given no permission to film at the sites the studio visited, and so the glimpses of the prison we see are not so much documented as they are curated. ↩

-

Frank Gehry, famous stoner, has apparently spent one night in jail, for marijuana possession. Bill Keller, “Reimagining Prison With Frank Gehry,” The New Yorker, December 21, 2017, link. ↩

-

See, for example, Brendan Cormier’s observation: “He is given to repeating words like ‘humanity’ and ‘human-scale’ in talking about how architecture should be.” In Cormier, “I Watched Frank Gehry’s MasterClass So You Don’t Have To,” Avery Review 26 (October 2017), link. This “humanity” is also implicit in the following statement: “For years I had been looking for an architect to work with as a partner to reimagine what a prison might look like in a different era in this country. An era of low incarceration and a commitment to reform, rehabilitation, and reintegration of prisoners into society,” says now-former Open Society Foundations president Christopher Stone, whose work on the world’s “insoluble” problems of justice, migration, and rights welcomes the less constructive approaches of design thinking—more specifically “imagination.” ↩

-

From Paul Goldberger’s review, “Good Vibrations,” The New Yorker, September 29, 2003, link. ↩

-

Although: “I’m very proud of the effect of what happened in Bilbao. Three and a half billion dollars has come to the city since the building opened. It changed the character of the city. It changed the politics. Just a little building did that.” Spencer Bailey and Frank Gehry, “Frank Gehry Is Still Building His Legacy,” Surface, November 2, 2015, link. ↩

-

In the exhibition catalog for his 2015 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, a show that boasted 225 drawings, 67 models, and other documentation of more than sixty projects, “The Prison” is mentioned once. A refusal of the accusation that Gehry’s treatment of any sculptural object as “inert”: instead, a “flow effect...preserves the dynamics of the overall morphogenesis so that the fish does not become an inert body, a prison (Folly: The Prison Project, 1983).” The fish could not be a prison, but, like, what about the prison? Centre Pompidou Press Kit, “Frank Gehry,” September 20, 2014, link. ↩

-

Matt Chaban, “Frank Gehry Really, Really Regrets His Guest Appearance on The Simpsons,” New York Observer, September 5, 2011, link. ↩

-

You can find the description for the last concert hall studio in the Yale course listings for spring 2016, link. ↩

-

Gehry’s last concert hall studio coincided with Bob Stern’s last semester as dean. ↩

-

Deborah Berke in Frank Gehry: Building Justice. ↩

-

From the course description for the spring 2017 prison studio: “The project site will be the Cheshire Correctional Facility in Cheshire, Connecticut. Built in 1913, the building was originally designed to hold boys and young men. Currently, the building has a capacity to house up to 1,600 adults, having undergone multiple modification and additions over the past 100 years. Projecting forward, the facility will be re-imagined to house three hundred men convicted of serious, primarily violent offenses, serving sentences between five and fifteen years. The existing building serves as a point of departure and can be re-used or discarded entirely. The speculative nature of the project, based on contemporary research and theory, requires you to examine closely the role of architecture as a means to provide safety, refuge, and facilitate personal transformation alongside its ability to reflect or enact the will of society. The project asks you to design a new typology, exploring the unimagined.” See “Advanced Design Studio: Frank Gehry,” Yale School of Architecture, link. ↩

-

Matthew Kabala reflects, “I think what Frank did best for us was really trying to encourage all of us as students to dig deep, to get personal, to have a visceral kind of response to what we were dealing with. To not simply stay in the world of policy or design theory but to make it very personal. What would it mean for us to be in these spaces or for our family members?” ↩

-

Alex Busansky reflects on his trip with the studio to Norway’s Halden and Balstoy Prisons, and Suomenlinna Prison, near Helsinki in Finland in his writing for Impact Justice. See Alex Busansky, “Build It and They Won’t Come,” Medium, September 26, 2018, link. ↩

-

Jessica Benko, “The Radical Humaneness of Norway’s Halden Prison,” the New York Times Magazine, March 26, 2015, link. ↩

-

Bill Keller, “Reimagining Prison with Frank Gehry,” The New Yorker, December 21, 2017, link.

This semantic reconceptualization was not limited to our individual projects, but extended to all our discussions regarding the topic of incarceration: we called inmates “residents,” guards were “correctional officers,” cells were “rooms,” etc. It was a collective exercise in reformulating the lexicon of prison architecture in an attempt to assert a sense of humanity and of compassion—an enterprise strongly supported by Frank, who exhorted us throughout the whole semester to be empathetic, and to use emotion as the guiding light of our designs.[^26]

-

See reporting from The Marshall Project on the perceived relationships between crime and immigration: Anna Flagg, “The Myth of the Criminal Immigrant,” The Marshall Project, March 30, 2018, link. And for a breakdown of the offenses by the population of non-citizens detained and deported under “criminal alien” convictions during the Obama administration, see Christie Thompson and Anna Flagg, “Who Is ICE Deporting?” The Marshall Project, September 26, 2016, link. ↩

-

Doreen St. Felix, “The Troubled Teens of Netflix’s ‘Girls Incarcerated,’” The New Yorker, April 30, 2018, link. ↩

-

It should be said that Yale and SCI-Arc are certainly not the first architecture schools to consider the question of the prison in relation to its reform or its abolition. Joyce Hwang coordinated an undergraduate studio at the Buffalo School of Architecture in 2013 that looked at alternate configurations of incarceration. Columbia GSAPP and Barnard professor Leah Meisterlin has taught undergraduate studios at Rikers to juvenile detainees alongside Barnard students—a course made impossible by recent changes to Rikers’ policies regarding volunteer educators. And Laura Kurgan instructed an advanced architecture studio focused on closing Rikers at Columbia GSAPP in the fall of 2016—all before Gehry’s The Future of the Prison studio debuted at SCI-Arc in the spring of 2017. Those are just people I happen to know personally! I’m certain there have been others! ↩

-

He mentions this in the ADFF Q&A and in his appearance on Savona Bailey-McClain’s podcast, “The State of the Arts NYC,” October 18, 2018, link. ↩

Gabrielle Printz is a co-founder of feminist architecture collaborative, an architectural research office that works around the design of the body, nationality, and labor. Her own preoccupation with the prison took the form of c-a-r-trip.us, a thesis project for the Master of Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture program at Columbia.