After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the near destruction of New Orleans’s shotgun houses—a housing type strongly associated with the American South—has left local historians and preservationists with the difficult task of preserving a beloved yet seemingly unimportant building tradition. As a ubiquitous fixture of the everyday, it is easy for one to assume the shotgun house’s insignificance. Jay D. Edwards writes in his seminal essay “Shotgun: The Most Contested House in America” that a considerable portion of the buildings damaged during the hurricane were shotgun-related structures, which comprises about 60 percent of New Orleans’s housing stock. Edwards also points out that only eight incomplete surveys of shotgun-related structures, out of a total of 147 structures, have been recorded for the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) for the New Orleans Parish.1 Considering the lack of architectural appreciation for this specific housing type, how does one make a case for its protection?

The answer lies in advocating for the historical significance of the shotgun house. If one follows the guidelines set out by the United States National Register of Historic Places to evaluate a site’s potential for preservation, a historically significant piece of built heritage must retain its integrity for it to be protected from demolition or neglect. And integrity, according to the Register, is the ability of a property to convey its significance. However, what is significance? Many nontraditional buildings and sites, segments of the everyday, fall short of meeting this standard for protection. Often these failings come in the form of a lack: of original building fabric or of association with an historic event or figure. This essay argues that a crucial part of the historical significance of the shotgun house lies in the construction of its historical being—that is, why and how historians have debated its place within the context of American architectural history. As scholars have engaged with the historical origins of shotgun houses, acts of conflict, whether in the form of revolution, slavery, cultural resistance, or adaptation, have constantly shifted from the foreground to the background of historical analysis—rendering this vernacular tradition uniquely able to manifest the dynamics of history and race in the United States. It is this scholarly tension over the beginnings of the shotgun house that elevates its status to a more complex being, a built heritage worthy of protection through its multilayered historiographic creation.

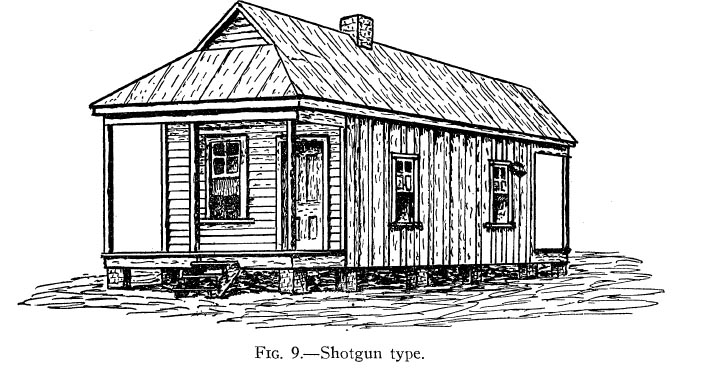

Historians generally agree that the term “shotgun” was first called into academic existence by Fred B. Kniffen in his 1936 fieldwork study “Louisiana House Types.” Besides bestowing academic legitimacy to a folk term used by locals living in Louisiana at the time, Kniffen visually renders the shotgun type within a larger methodological framework that identifies specific housing types in Louisiana. The “shotgun” type finally makes an appearance after the Built-in Porch, the Attached Porch, the Porchless, the Open Passage, and the Mid-Western or “I” types: “Shotgun type: the folk-term here employed is commonly used in Louisiana to designate a long, narrow house. It is but one room in width and from one to three or more rooms deep, with a frontward-facing gable.”2 Kniffen associates shotgun houses with Louisiana’s waterways, marking them on a detailed map along the “coastal bayous but also significantly extending in narrow bands far up the Ouachita and Red.”3 Following this initial study, historians begin to construct the historical origins of this form, a form that had been prevalent in Louisiana, mainly New Orleans, since the 1870s.4

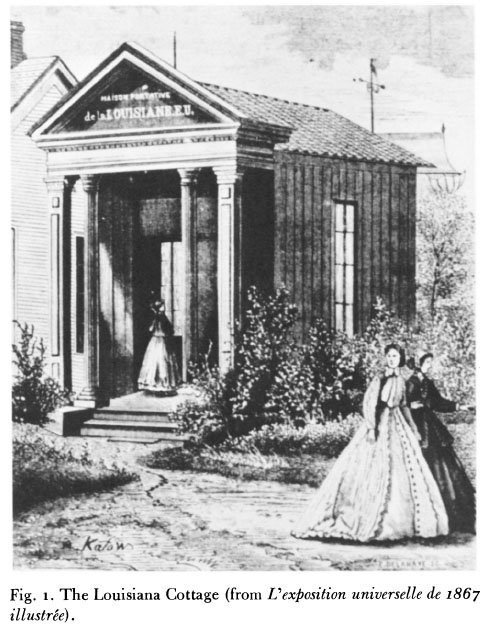

Samuel Wilson Jr., a prominent New Orleans historian and architect, contributed substantially to the early studies of the origins of the shotgun house. From his Impressions Respecting New Orleans by Benjamin H. B. Latrobe, 1819, Wilson is known for naming the “narrow-lot theory.”5 Later, he writes briefly on the prefabrication of shotgun “cottages” in his 1963 article “New Orleans Prefab,” 1867, without offering a more considerable origin theory. According to Wilson, shotgun houses were constructed to house “emigrants from [a] crowded Europe.”6 An 1849 quotation he includes from the notarial records of H. B. Cenas describes the type as “a portable style, with canvas and cement roof.” However, Wilson also includes a woodcut illustration of the type as it was featured at the Paris Universal Exposition in 1867, elegantly clad in the Greek Revival.7 Wilson later quotes from a Roberts and Company catalog that describes the popularity of “attaching” Greek Revival elements to shotgun houses:

Thus, Wilson’s account suggests that the shotgun house might have been a housing type used by various socioeconomic groups. Although not an explicit view on race and class, it is important to note Wilson’s position on the universality of this type.

However, in the 1970s, on the heels of the civil rights movement and as academia began to actively reflect an increasing appreciation for the cultural contributions of black Americans, the shotgun became a symbol of the quintessential “African American” architectural type. Although discussions of the “everyday” or the “anonymous” had permeated academia since the 1930s, this period saw a rapid rise in the study of vernacular architecture as scholars began to further investigate the contributions of minority groups in building culture.8 Until this moment, vernacular architectural studies had concerned itself primarily with pre-industrial, colonial, and rural buildings of the developed Western world, but the 1970s saw a shift toward other types of traditional buildings outside of the Western sphere, including architecture in Africa and the Middle East.9

Within this cultural current, the work of folklorists like John Michael Vlach became particularly vital in reframing the architectural importance of the shotgun. Vlach writes in his 1975 dissertation, “Sources of the Shotgun House,” that “very little of the material folk culture of American negroes has ever been considered as derived from or in any way connected with the African cultures from which they are descended.”10 Vlach argues that the “shotgun house seemingly developed in New Orleans about the same time that there was a massive infusion of free blacks from Haiti. This circumstance suggests that the origins of the shotgun are not to be found in the swamps and bayous of Louisiana but on the Island of Haiti.”11 Invoking the work of Melville J. Herskovits, an anthropologist who was instrumental (among many others) in establishing African and African American studies in American academia in the 1960s and 1970s, Vlach emphasized the historical link between black survival of white supremacy and black American material culture.12 Expounding on Herskovits’s The Myth of the Negro Past, which argued against the denial of a “black cultural legacy in Africa,” Vlach writes:

If an ethnic group shared a recognizable history, this argument goes, they must be a cultured people despite centuries of torment and struggle. Vlach goes on to suggest that,

descriptions of shotgun houses and their historical antecedents in Haiti and West Africa provide data that are not only an addition to the current knowledge about Afro-American artifacts, but are also useful for future cross-cultural comparisons…certain areas of the theory of Africanism are not clearly outlined…[and] the existence of an African derived house…must cause the controversy of Afro-American tale origins to be rethought.13

Vlach concludes his piece with an allusion to Wilson’s 1963 article on prefabrication in 1867—the presence of whites living in shotgun houses proves the transferability of black American architecture.14 Thus, the shotgun, an “archetypal” black American housing type, has made significant contributions to the built American cultural landscape.

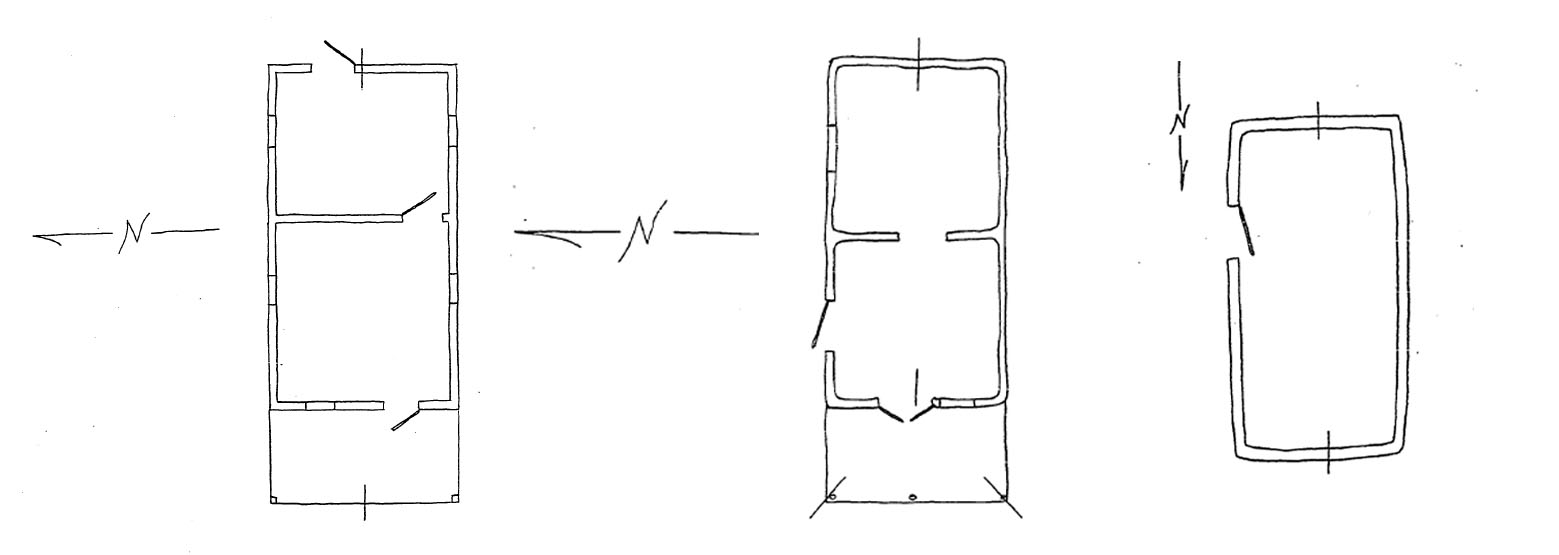

Vlach ties the influx of refugees fleeing the Haitian Revolution between 1791 and 1803 in the city of New Orleans to the upswing of shotgun house construction through typological characterization and comparison.15 First he defines the shotgun house as a “one-room wide, one-story high building with two or more rooms, oriented perpendicularly to the road with its front door in the gable end”—a slight variation on Kniffen’s initial definition by locating the structure in relation to the street. Vlach argues that specific features of the shotgun, most notably the placement of its front door and its orientation, “violate the standard canon for American [or Anglo-American] folk building.” Therefore, because of its unique typology, the origin of shotgun houses must lie in the cultural connection to “African beginnings.”16 Vlach later uses comparative sketches in the second volume of his dissertation to investigate the similarities between shotgun houses in New Orleans, Haiti, and West Africa and then to argue that the black American shotgun house has roots in Haiti, which in turn has roots in West Africa:

The Atlantic Slave Trade carried people and their building traditions from Africa to Louisiana—the shotgun house is evidence of this cultural endurance. This linkage emerges again as a major point of discussion in the twenty-first century as scholars, especially Edwards, assert that the “theories of the origins of the shotgun lie deeply enmeshed in larger cultural debates on race and authority in the city.”17

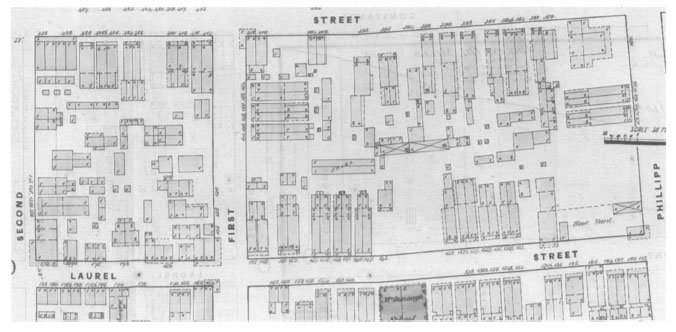

As more recent studies point out, both Wilson’s and Vlach’s earlier assessments eventually render the other invalid. According to Wilson, the “narrow-lot” theory proposes that the shotgun is a “late-genesis” type that appeared after 1840, while Vlach argues that the type appeared much earlier, and is the progeny of a slightly altered prototype. In the edited volume The Creole Faubourgs, Roulhac Toledano and Sally Kittredge Evans, following Wilson’s origin theory, speculate that the two-bay shotguns “might be an outgrowth of the creole single dwelling type,” suggesting an expansion into slimmer lots, resulting in the now recognizable shotgun form.18 However, very little is offered on origin beyond a detailed typological definition of various types of shotgun houses.19 Vlach seems to ignore Wilson’s narrow-lot theory in his 1978 exhibition, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. Invoking his previous doctoral thesis, he argues, “While black builders have made their contribution to elite architecture since the first years of America’s existence, the greatest contribution of Blacks to American building custom and precedent has been in the realm of the common dwelling house.”20 Vlach makes the claim, against Wilson’s, that shotgun houses express black Americans’ active engagement with their surroundings and their application of cultural values to building traditions—pointing out again that the shotgun house crossed national borders (between West African countries, Haiti, and America) as well as racial borders beginning in the 1870s, when the form “proved very popular for economic reasons and…was commonly built as a cheap rental house.”21 Early maps of the city prior to 1840 would solve the origin issue; however, according to Edwards, the first expansive and detailed Sanborn maps of New Orleans did not exist until 1876, and by that time shotguns were common but still not dominant.

If the work of Wilson and Vlach outlines the contours of the shotgun house’s historical construction in the 1960s and 1970s, Jay D. Edwards’s more recent interpretations understand the shotgun house through a broader cultural perspective. He suggests that the best way to resolve the origins of the shotgun house would be to historically re-investigate “shotgun-like” structures, which he eventually renames Atlantic Linear Cottages. Following the historiographical tradition of critiquing and re-evaluating the work of predecessors, Edwards examines the evidence put forth by both Wilson and Vlach, refutes or supports their theses, and moreover draws on the postcolonial concept of creolization theory, offering new ways into the question of “why traditional sources have failed so completely to record a once popular house type.”22

Vlach’s theories on the direct relationship between the shotgun house and the arrival of Haitian refugees, Edwards notes, are unfortunately not supported by enough evidence. However, because of the growing scholarship, Vlach’s claim has gained supportive evidence that shows the existence of the shotgun-like structures between 1805 and 1840.23 Training his sights on Wilson, Edwards points out that,

Although a true assessment of the possible origins of this type, as Edwards reassures, this claim is incomplete; it does not account for social and cultural values present during the period, which are the focus in Vlach’s early-precedent claim. From this critique, Edwards cautions that, “those who believe that the shotgun is largely a late nineteenth-century addition to the cultural landscape generally tend to undervalue its significance when considered against other typical New Orleans houses, for example Greek Revival mansions, Creole cottages, and port-cochere townhouses.”24

Edwards does corroborate, with evidence and sources not previously available, Vlach’s earlier suggestion that shotgun-like structures did exist in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) since the early eighteenth century and delves deeper into the cultural, economic, and technical connection to refugees of the Haitian Revolution. French colonists, African slaves, and affranchis (free people of color, also called gens de couleur libres in New Orleans) all migrated during the revolution to Louisiana. The last class, made up of people of mixed race, became the petit bourgeoisie of New Orleans. It was from this class that we see the most significant influence on New Orleans vernacular architecture, namely in shotgun house construction. Thanks to this flow of refugees, the city experienced housing shortages from 1809 to 1810, and refugees, in response, began building “temporary fringe housing in and around the edges” of the city. Edwards goes on to organize a database of shotgun-like structures built prior to 1840, identifying four linear cottage types that had existed in the city between 1790 and 1830: Appentis Cottages, Cabannes and Shanties, Creole Maisonettes, and Single Shotgun and North Shore Cottages. All are defined as being a single room wide and two or more rooms deep, with a roof ridge running perpendicular to the street and an entrance facing the street. “If we consider shotgun houses to be linear cottages with gabled or pedimented fronts,” Edwards proposes, “there is evidence that they begin to be built in relatively small numbers in the first decade of the nineteenth century.”25

Edwards’s work also further expands on the social, architectural, and technological values that gave rise to the proto-shotgun. One such condition, Edwards begins, is the “landlady effect,” known as plaçage, or formalized hypergamy, which appeared after an increase in the gender gap in the gens de colour libres caste around the 1820s. Lighter-skinned black females began to be matrimonially contracted to well-to-do white males, who were then financially obligated to their female partner. These arrangements were typically temporary, however, and often led to the abandonment of the black female partner by her white “husband/lover” for a white member of his own class. Many of these women lived in “quadroon quarters,” or casa chicas in Spanish slang. Financially independent from their previous marriages, these women commissioned both their own houses and rental properties on narrow lots and created an atmosphere in which narrow houses, particularly the linear cottage, came to be associated with a certain lifestyle.26 The landladies hired free men of color, former refugees of the Haitian Revolution, as carpenters, linking Haitian building culture to free women of color with the means to support themselves and commission proto-shotgun-like structures.

By the 1830s and 1840s, in Edwards’s account, shotgun-like structures were commonplace among free people of color, their renters, and white and black businesspeople. This leads to an examination of the economic impacts that furthered the appeal of the shotgun house typology:

The costs of construction are clearly an important factor in the selection of a building type. Inexpensive, machine-cut framing material in standard sizes was becoming available in these decades. Most shotgun-type houses could be built without the use of heavy framing and specially fitted roof trusses. Ceiling joists did not have to support a second story as they did on the post-1820 Creole cottages.27

Ease of construction would allow those with the means to imitate one of the most fashionable architectural styles of the day, which, in the early to mid-nineteenth-century United States, was the Greek Revival. Edwards notes the appearance of architecture pattern books, mostly epitomized in the work of Asher Benjamin and Minard Lafever, which became immensely popular with ordinary builders not trained as professional architects. In around 1834, these books arrived in New Orleans through the influence of James Gallier and James Dankin, architects who worked in the city in the nineteenth century. From these imports, the Greek Revival became an easily reproducible form in vernacular building. Edwards also points out that this stylistic revolution coincided with the increase of gable-fronted shotgun-like structures and the end of Creole cottage construction from 1835 to 1845, highlighting the difficulty of stylizing a Creole cottage compared to the simple form of the shotgun house. This gave the shotgun added economic appeal, for not only people of the lower class but also businessmen and merchants who wished to emulate current architectural trends. Edwards’s work shows the critical importance of including a wider cultural context in architectural investigations on the historical significance of shotgun houses.

Taking a slightly different approach from Edwards, though not specifically focused on the precedents of the shotgun house, Louis P. Nelson’s 2011 article, “The Architectures of Black Identity: Buildings, Slavery, and Freedom in the Caribbean and the American South,” challenges the now commonly held belief perpetuated in the 1970s that black American culture has historical connections to Africa that were not severed by slavery. Nelson does not suggest that black American culture is a mere copy of white Anglo-American architecture—rather, he posits that black American structures are the result of black Americans’ creatively interpreting their environment. Acknowledging the past work of scholars of black architectural traditions, including Vlach, Nelson suggests that, for example, the retrofitted shipping-container house prominent in Jamaica is an excellent example “of the appropriation and creative reuse of limited available resources,” by enslaved and possibly free blacks. Alluding to the historiographic debates surrounding the shotgun house, Nelson refers to Vlach’s initial tracing of shotguns in New Orleans to Haiti: “but even acknowledging this regional distinction, the shotgun house certainly appears to be a mainland manifestation of the free black architecture found across the early nineteenth-century Caribbean.”28

As Nelson was publishing his article on Jamaican shipping containers, Edwards writes further on the creolization theory that he first alluded to in his essay in 2009. In “Creolization Theory and the Odyssey of the Atlantic Linear Cottage,” Edwards attempts to use the shotgun house or the Atlantic Linear cottage as an example of “creolization,” relying on archival research and contemporary ethnographic studies of “historically and culturally related architectural forms” present in shotgun-like structures.29 Edwards admits the challenges of defining “creolization” as specialists in the area of postcolonial theory and Atlantic studies disagree on its theoretical underpinnings and how it may differ from other cultural processes. Edwards writes that the benefit of adopting a dualistic view of creolization theory, synthetic and adaptive, enables us to seek cultural analysis beyond “fixed forms,” urging us to explore the “relevant levels of social interpretation” of a type. Edwards urges us to direct our attention on central trend of “multiple sets of interpretations employed by different actors in and around the dwelling.” Edwards then provides an overview of his evolved historical understanding of the creation of the Atlantic Linear Cottage. He first begins with the sixteenth to mid-eighteenth centuries in Upper Guinea, where, “the foundations of world colonial architecture were laid,” tested, and then abstracted elsewhere.30 Second, Edwards travels to Hispañiola in the early sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century, where he suggests that African Creole galleries were introduced on slave plantations, leading to the creation of the ti-kay in Haiti. Edwards writes:

Stage three of Edwards’s analysis finally brings us back to nineteenth-century New Orleans, where, with the increase of refugees from the Haitian revolution, linear cottage construction increased.31 Edwards rehashes familiar topics—the various types of shotgun-like structures in the city and the relationship to lot-rental formation—but this time within the context of creolization theory. Curiously, when revisiting the connection to the Greek Revival, however, Edwards introduces a new concept, “decreolization,” which occurs, when “local dialects become increasingly modified in the direction of a national standard, or acrolect.” The appearance of Greek temple forms on the exterior of linear cottages when the style was fashionable would suggest that the owner had the financial means and architectural taste to replicate these motifs. However, Edwards notes that architectural elements often applied to linear cottages would have been “crude” versions of forms typically found in well-known (and often expensive) pattern books like ones designed by Benjamin and Lefever. Therefore, the architectural result would be the adaptation of a form to the environment, a tenet of Edwards’s creolization theory. The acknowledgement of the black diaspora and the utilization of a housing type by various socioeconomic groups adds further complexity to the historical trajectory of this form. Edwards admittedly concludes in “Creolization Theory” that, “creolization models are incomplete in that they are expressions of only the most general aspects of radical cultural change. What is required for successful interpretations of specific cases…is a multilevel conceptualization of the processes involved.”32

Historians may never agree on the historical origins of the shotgun house; however, because of its unclear beginnings, this type allows historians to actively reinvestigate past and current claims. Edwards suggests that “architectural historians need to critically reexamine the implications of the strategies they adopt in the telling of their tales. They might wish to consider how circumventional processes of identity formulation and cultural resistance might be more central to the history of architectural forms.” This may be a helpful way to think about the historical origins of shotgun houses, yet as Edwards demonstrates in his later work, more evidence and theoretical understanding is needed in order to fully comprehend this type’s historical narrative. Indeed, the shotgun house may be one of the lowliest types—but its richly contested historiographical evolution rivals debates around the highest of architectural masterpieces.

-

Jay D. Edwards, “Shotgun: The Most Contested House in America,” Building & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, vol. 16, no. 1 (Spring 2009). The Historic American Building Survey only includes structures documented and recorded by staff, not the total number of buildings in the city. ↩

-

Fred B. Kniffen, “Louisiana House Types,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 26, no. 4 (December 1936): 186. Curiously, Kniffen disregards in his study urban centers because they “introduced complexities out of all proportion to the areas they occupy,” 180. ↩

-

Kniffen, “Louisiana House Types,” 191. ↩

-

William B. Knipmeyer, a PhD candidate at Louisiana State University in 1956 under the direction of Kniffen, focused his dissertation on the material culture of the “descendants of French Colonists.” There he provides further detail on the characteristics of shotgun houses; however, he does not delve deeper into the origins of the building type. William B. Knipmeyer, “Settlement Succession in Eastern French Louisiana” (PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1947), xi. ↩

-

As will be discussed later in Wilson’s edited volume New Orleans Architecture: The Creole Faubourgs, this “narrow-lot” theory, the subdivision of property into slimmer sections, appears to only partially explain the existence of shotgun houses. Samuel Wilson, ed. Respecting New Orleans by Benjamin H. B. Latrobe, 1819 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), 42. ↩

-

Samuel Wilson Jr., “New Orleans Prefab, 1867,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 22, no. 1 (March 1963): 38. ↩

-

The “Celebrated Louisiana Cottage” won a silver medal for the United States and a bronze medal for Louisiana at the 1867 Exposition. Wilson, “New Orleans Prefab, 1867,” 38.

The selection covers over 700 different molding profiles, in addition to balusters, handrails, newel posts and complete spiral stairs, ornamental fence pickets, exterior cornices, dormer windows, elaborate front doors, and ninety-five different designs for the jig-saw eaves brackets so familiar on New Orleans old-fashioned shotgun cottages.[^8]

-

Some work prior to the 1970s that scrutinized the “everyday” include Henri Lefebvre’s The Critique of Everyday Life (1947); Sigfried Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (1948); Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture (1957); Bernard Rudofsky’s Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture (1964). ↩

-

Marcel Vellinga, “The End of the Vernacular: Anthropology and the Architecture of the Other,” in “Architecture,” ed. Markus Blakenhol et al., Etnofoor, vol. 23, no. 1 (2011): 178. ↩

-

John Michael Vlach, “Sources of the Shotgun House: African and Caribbean Antecedents for Afro-American Architecture” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 1975), 1. ↩

-

Vlach, “Sources of the Shotgun House,” 73. ↩

-

Besides Herskovits, Carter G. Woodson and Lorenzo Johnson Greene are both credited with pioneering the creation of official studies in black American history and culture in academia. See Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, The Early Black History Movement, Carter G. Woodson, and Lorenzo Johnston Green (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

Without any heritage of merit the Negro could be looked upon as human raw material and a source of labor, a commodity and a tool. Herskovits saw that American racism could be effectively countered by calling attention to the total history of American blacks. He thus struck at the root of racist philosophies. Rather than beginning in 1619, the history of the Negro had to be pushed back to include the African experience.[^14]

-

Vlach, “Sources of the Shotgun House,” 22. ↩

-

In academia, it is interesting to note the concept of “transferability” especially when we consider the value of an object. Who ultimately determines an object’s value? And how does this value translate within a dominant culture? ↩

-

According to Edwards, about twelve thousand Haitian refugees arrived in Louisiana between 1791 and 1809. ↩

-

Vlach, “Sources of the Shotgun House,” 29–32.

The shotgun house allowed some important African values to be maintained without extensive modification, and thus helped slaves and later free Blacks endure dreadful social conditions…they thus survived the experience of slavery largely intact and served as a basis for making decisions about house design. The choices made were understandably African.[^19]

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 62. ↩

-

Roulhac Toledano, Sally Kittredge Evans, and Mary Louise Christovich, “Types and Styles,” in New Orleans Architecture: The Creole Faubourgs, ed. Samuel Wilson, Jr. (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 1974), 71. ↩

-

“All antebellum variations of the shotgun have certain common characteristics: they are usually covered with a roof hipped on all four sides, although early brick examples sometimes have gabled back ends. The hip roof is much steeper than the type found on late Victorian shotguns and it is usually characterized by a cant at the edge or a definite double pitch. They are built about a foot off the ground with a solid brick chain wall in front and brick piers on the sides. Chimneys are located at the center ridges of the roofs.” Toledano, Evans, and Christovich, “Types and Styles,” 71. ↩

-

John Michael Vlach, “Architecture,” in The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978), 122. ↩

-

Vlach, “Architecture,” 131. ↩

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 69. ↩

-

Edwards includes work by other architectural historians who believe that there is still little evidence of the existence of the shotgun prior to the American Civil War. Malcolm Heard, for example, argued in 1997 that “it was decades later however (relatively late in the nineteenth century) when the shotgun as we know it came to be built in large numbers in New Orleans.” French Quarter Manual: An Architectural Guide to New Orleans’s Vieux Carré (New Orleans: Tulane School of Architecture, 1997), 48.

one difficulty with Wilson’s Creole cottage-genesis theory is that if before 1840 there were comparatively few single-wide linear cottages to act as models for the expanded shotgun, there were also comparatively few single-room-wide Creole cottages, as revealed by surviving examples, contemporary poster sale images of the New Orleans Notarial Archives, and the 1876 Sanborn Maps.[^27]

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 65. ↩

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 66–74. This essay will not dive deeper into the specifics of Edwards’s precedent shotgun-like structures. What is important in this comparative analysis is the abundance of proto-shotgun-like houses, which lends to the scholarship of the shotgun’s origins. Historians should take care to search the historical record for “shotgun-like” structures as oppose to “shotgun” structures in order to widen their pool for investigation. ↩

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 78. ↩

-

Edwards, “Shotgun,” 80. Edwards reflects on the methodological complexities of his approach: “The research problem is to acquire reliable comparative cost data for linear cottages and Creole cottages for the same period, based on approximate square footage, but it has not been possible to do this with precision. Building contracts for the early nineteenth century (mostly in French) do not clearly describe houses as Creole cottages or linear cottages, and the word shotgun was unknown. Floor plans are generally not attached to the contracts, though cost of building is always specified.” ↩

-

Louis P. Nelson, “The Architecture of Black Identity Buildings, Slavery, and Freedom in the Caribbean and the American South,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 45, no. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2011): 177, 183, 188. ↩

-

Edwards, “Creolization Theory and the Odyssey of the Atlantic Linear Cottage,” in “Architecture,” ed. Markus Balkenhol et al, Etnofoor, vol. 23, no. 1 (2011): 51. Edwards based his fieldwork in Senegal, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Louisiana. He consulted archives in Washington, D.C.; New Orleans; Dakar; and Port-au-Prince, Haiti. ↩

-

Edwards, “Creolization Theory,” 56–57.

the resulting patterns of contact [between colonized, the colonizers, and the environment were prerequisite to the creation of the urbanized Linear Cottage by the affranchis class of tradesman and artisans. Without these cultural interminglings, the ti-kay would have remained a humble rural house type, rather than a nation-wide phenomenon adapted to both rural and urban environments.[^35]

-

Edwards includes that there were “even greater” numbers of immigrants traveling from Cuba between 1803 and 1809 to New Orleans compared to Haiti. Edwards, “Creolization Theory,” 66. ↩

-

Edwards, “Creolization Theory,” 72–74. ↩

Charlette Caldwell is currently a first-year PhD student studying architectural history and theory at GSAPP. As a historian and preservationist, her research interests include the history of American architecture, specifically from the nineteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth century, and the study of vernacular architecture. Prior to attending GSAPP, Charlette has worked on the conservation of genocide memorials in Rwanda, preservation advocacy in Philadelphia, 3D modeling in Washington State, and architectural research for Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates and the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania.