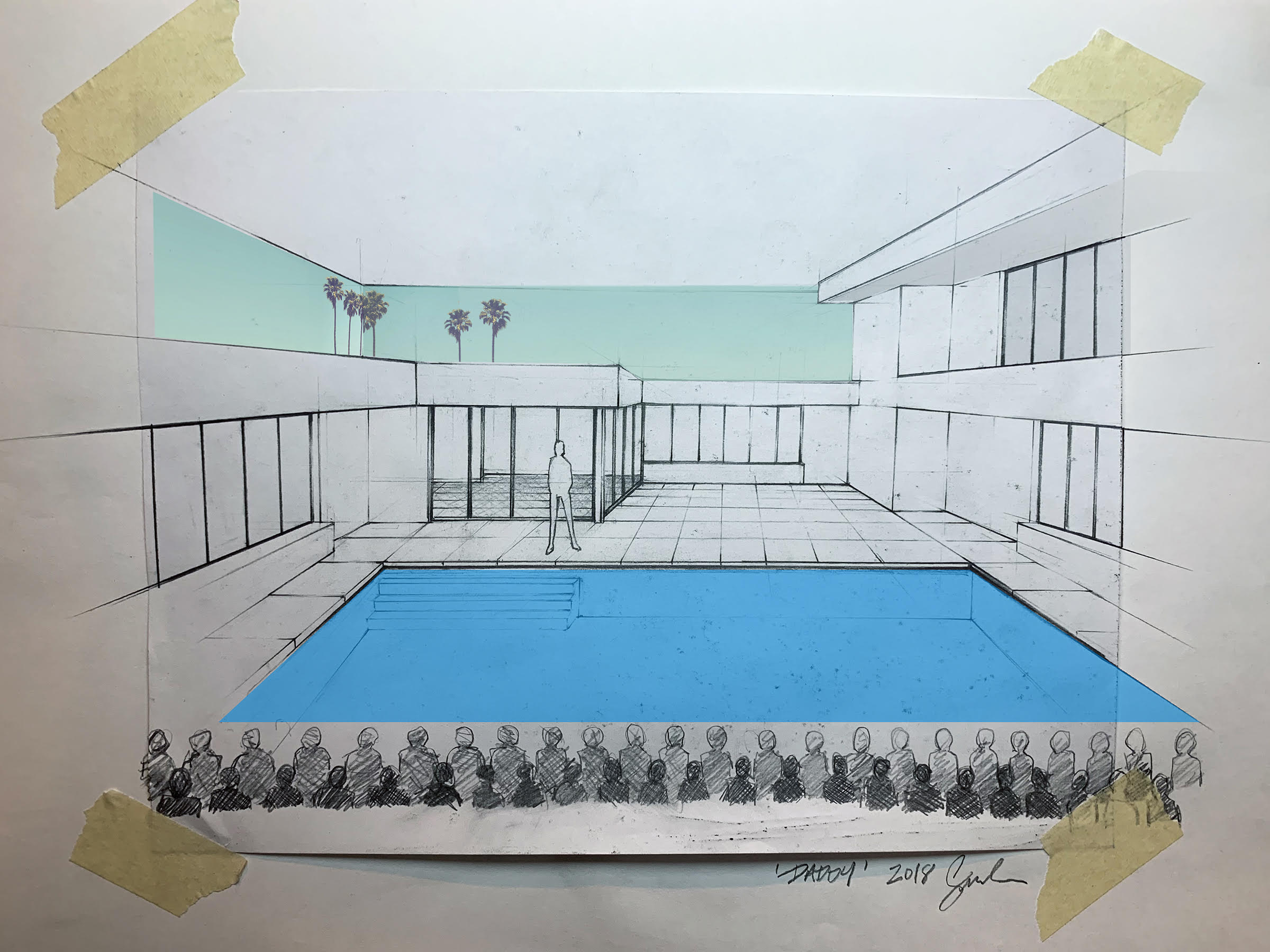

Before us, downstage, there is an expansive

infinity pool. Perhaps there are inflatables?

Perhaps not. Upstage there are five poolside

chaises longues.

Behind those, a glass wall and a sliding door

leading to a stark white room that may or may

not have art on the walls. When the door is slid

closed you can’t hear what’s being said behind it.

FRANKLIN stands in the middle of the room

looking around. He is dripping wet and wearing

only a Speedo. He’s a bit more than drunk.

—Jeremy O. Harris, Daddy (2015)1

Jeremy O. Harris’s Daddy, the playwright’s latest work to open in New York, collides distant parts of the American landscape—the black American South and the ever-so-white Bel Air—in “distorted self-portraiture” of the script’s author, that also reflects the mode of collage that defines one of the play’s formative artistic precursors, David Hockney’s 1972 Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures).2 Daddy instrumentalizes the midcentury modernist villa, one of Los Angeles’s most enduring architectural tropes, as one of the play’s stars. Harris’s script engages on the one hand with the construction of a distinctly white, bourgeois class and on the other with the cult of the male body and the queer gaze, exacerbating the fracture between his characters and their attendant ways of life.

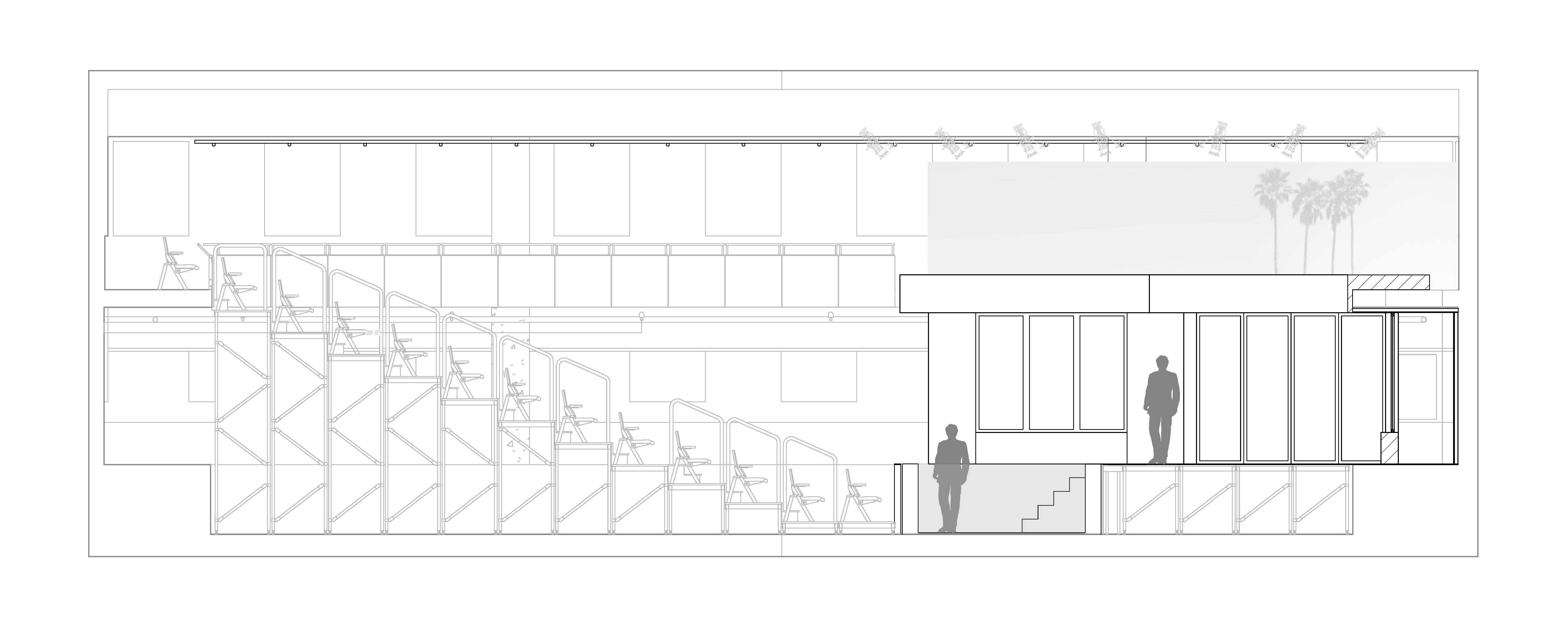

Daddy is staged as a site-specific architectural performance, albeit one transplanted to the stage from the Angeleno canyons. The action plays out poolside in the present day, in a 1:1 reconstruction of a Bel Air estate, zip code 90077, designed for Daddy’s debut by Matt Saunders, complete with functioning pool.3 The audience is seated where one might typically expect a citywide vista, equipping them with a view across the pool deck and into the glass enclosure of the modernist villa immediately behind. Imagine the scenography of A Bigger Splash with the architecture of Beverly Hills Housewife, both painted by Hockney in 1967. This literal reflection of view strips the domestic interior of the privacy otherwise granted by the villa’s typical isolation, delivering on the voyeurism implicit in modernism’s embrace of transparency. This puts the home’s residents—Franklin, a black twenty-something artist who still speaks with a hint of a southern accent, and Andre, the house’s white art collector owner and Franklin’s Daddy figure—at the fore in an architectural tradition that developed concurrent with the cult of the male body as evinced by the personal account of Harris’s artistic referent, Hockney.

While 2018’s Slave Play, staged at New York Theatre Workshop, was Harris’s first professional production, Daddy was written years earlier.4 In each play, a breadth of discursive hyperlinks appear before the audience and enrich the narrative context with a bibliography that warrants a deeper survey. This text unpacks the milieu of Daddy’s form, its script and the set detailed therein, understanding these as objects of design in order to focus a closer reading and consider the playwright’s long-term theoretical project.

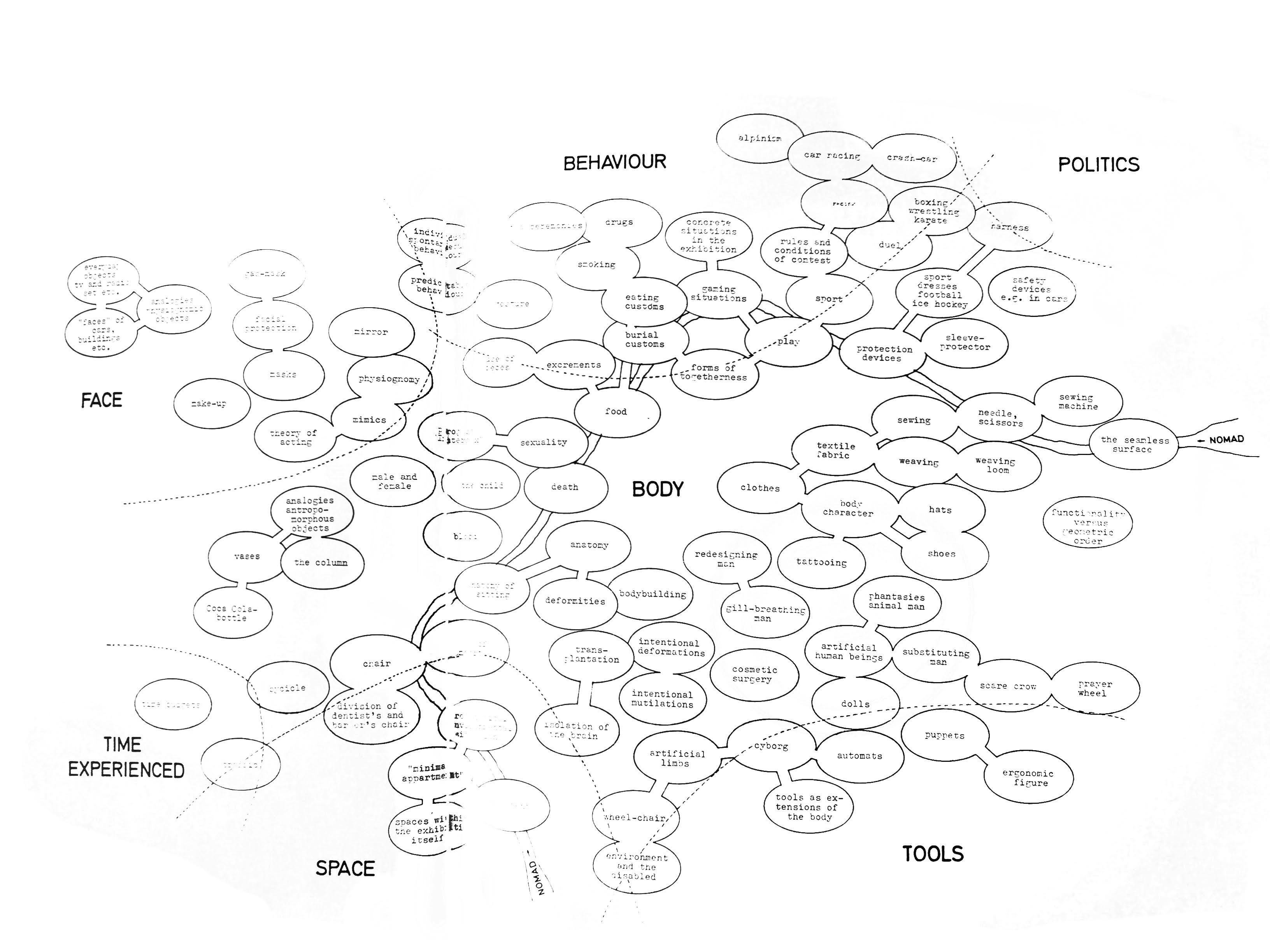

Hockney describes his mythical 1964 voyage to Los Angeles as having been magnetized by contact with a Julius Shulman photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House 21 (1959) and an issue of Physique Pictorial, produced by Bob Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild in Los Angeles.5 Mizer founded his agency in 1945 and began circulating images of the male bodybuilders native to Los Angeles, typically found exercising and exhibiting their fitness at Muscle Beach. Santa Monica is arguably the birthplace of modern fitness culture and perhaps the progenitor of the gym selfie. By the 1950s, it had become globally recognized, equipping its musclebound constituents with a cult of celebrity by way of mail-order subscriptions to catalogs like Mizer’s.

Right: Physique Pictorial, vol. 10, no. 01 [June 1960].

The construction of the “ideal” American body and Muscle Beach’s rise in the popular imaginary was distinguished by the backdrop of the developing nuclear threat in the Cold War climate of the midcentury. Speaking to anxieties around American preparedness and the physicality of its military-aged populace, former general Dwight Eisenhower founded the President’s Council on Youth Fitness by Executive Order 10673 in 1956.6 This was among the first in a series of executive branch missives on the issue of fitness and physique.7 In 1960, President-elect Kennedy published “The Soft American” in Sports Illustrated—itself founded only six years prior—to outline his steps toward federal intervention on the issue of physical health.8 The gyms of fitness experts Vic Tanny and Joe Gold began to embody the American identity at the new Western frontier and were crucial spaces of socio-political organization ultimately linked with the construction of an idealized citizenry. Following the Second World War, Tanny even took over the lease on a former USO facility in Santa Monica, further demonstrating the cultural reciprocity between the body in training and the body in service of the state. Unsurprisingly, many of Mizer’s films from the same period feature members of these gyms and fetishize models in military uniform.9

Shortly after Gold’s Gym opened in 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson launched the Presidential Fitness Award. A decade later, the design of the body resonated with new audiences as the Whitney Museum opened Articulate Muscle: The Male Body in Art in 1976, while in that same year the Cooper Hewitt, National Museum of Design in New York City, opened its inaugural exhibition, Man TransFORMS, directed by architect Hans Hollein. Orbiting the central figure of “THE BODY” in a structuring diagram of thematic bubbles in the exhibition catalog: “bodybuilding,” “death,” “cosmetic surgery,” “sexuality,” “redesigning man,” “dolls,” and “puppets,” among others.10 A year later, Pumping Iron opened in American theaters, further fostering the mainstreaming of mass fitness culture.

The subjects of Hollein’s thematic staging can be found in various forms in Harris’s play. Indeed, Franklin’s focus as an artist are large soft sculptures, or “weird dolls of black boys,” like deformed Cabbage Patch Kids: playthings to enable the performance of nuclear domesticity.11 The inhabitants of Daddy’s Bel Air villa reside precariously, more like Airbnb tourists than permanent residents, probing the limits of their newfound privilege.12

Harris’s script quotes Hilton Als’s White Girls to set the mood ahead of the first scene: “…there’s the bizarre fact that queerness reads, even to some black gay men themselves, as a kind of whiteness. In a black, Christian-informed culture, where relatively few men head households anymore, whiteness is equated with perversity, a pollutant further eroding the already decimated black family.”13 This seems to evade the comprehension of Harris’s titular character as he gives up more and more of his house out of an anxious, misplaced generosity (or something like it). Eventually a southern Gospel Choir appears on the terrace, standing in for “Franklin’s forgotten heart and soul.” Materialized as if by teleportation from Virginia—the playwright’s home state—its singers echo the voice messages left by his “soldier for Christ” mother, Zora, and symbolically accompany her on her stay once she arrives at the villa.14 The choir reclaims the infinity pool in a reverse architectural code switch—the pool impelled to serve instead as baptismal waters in rebuke of the perceived impiety of its site. Given that the intended residents of the house and so many others like it would have been white, there’s a satisfaction in the repossession of that space here—in the inclusion of black bodies in the American domestic narrative—only, it’s complicated. Zora enters with bible in tow, not at home with “haughty lovers of pleasure” (Second Epistle to Timothy, Chapter 3) and the presence of a Daddy at all. “For of this sort are those who creep into households…led away by various lusts.”15

The playwright’s notes at the top of the first act describe the instrumentality of the villa’s sliding glass door, which silences “what’s being said behind it” when closed. Sound, or its muted absence, stands in for the instructive notation of Hockney’s oblique white lines, which, denoting glass surfaces in several paintings in his California Dreaming series, elaborate the reflective qualities and basic invisibility of modernism’s favored perimeter. In Daddy, then, the frame of the house focuses vision—both of its inhabitants and of the audience—but declines the clarifying soundtrack of conversation between those inside and out, setting up the difference between seeing and fully grasping that describes the dislocated experiences of Franklin and his older white lover, and perhaps equally, Franklin and his mother.

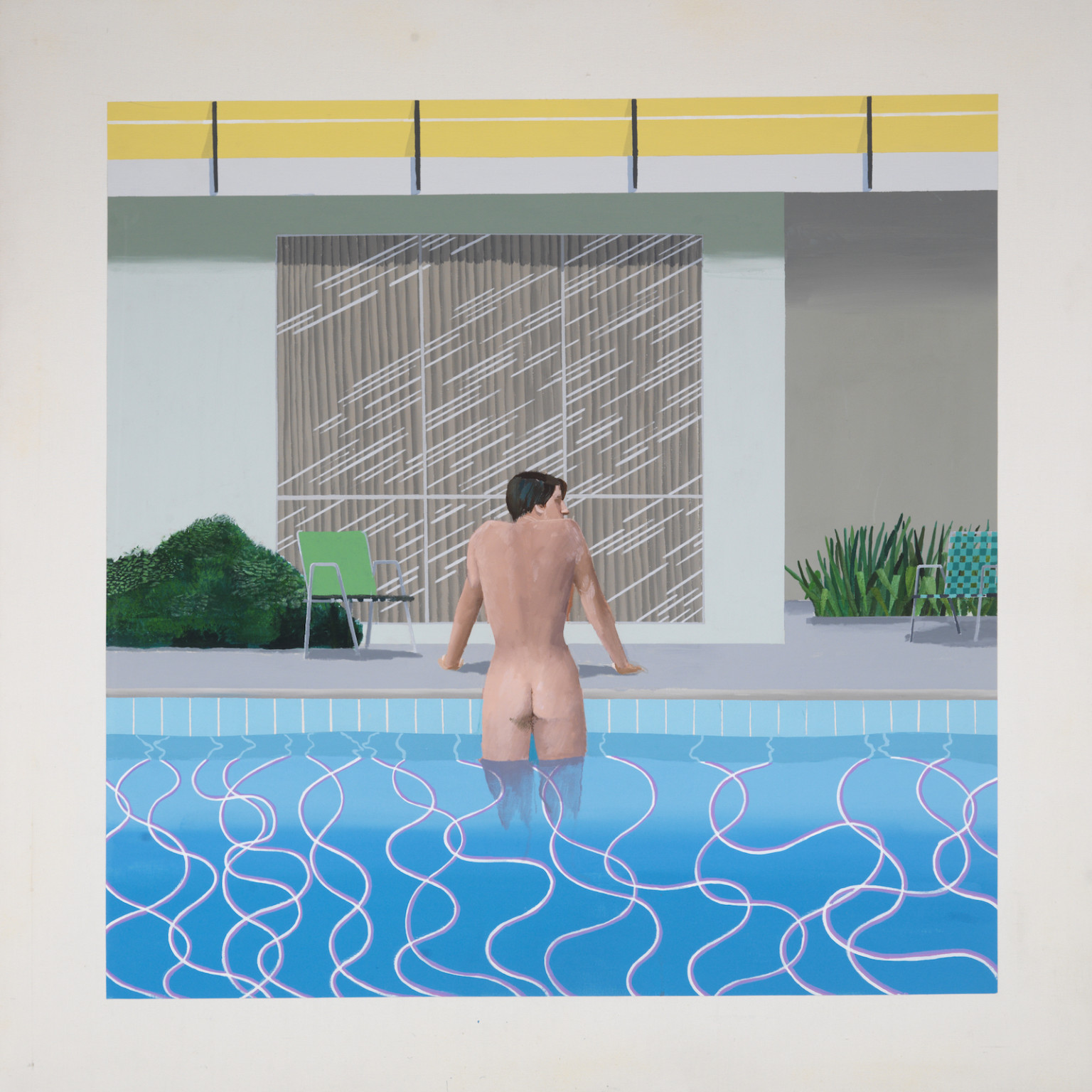

The first line in Harris’s “Notes on Style” instructs the reader to “Google David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972, if you’ve never seen it.”16 Hockney’s Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool even more exactly resembles a scene from Daddy, from the audience’s perspective facing the house from across the pool. In this painting from 1966, a nude nineteen-year-old Peter Schlesinger—Hockney’s lover at the time—emerges from the pool of gallerist Nicholas Wilder’s West Hollywood home. Floor-to-ceiling windows of a modernist residence are partially obstructed by Schlesinger’s frame in a pose borrowed from a Polaroid that Hockney had previously taken of his model posed against a sportscar.17 Equally, the painting could describe the poolside milieu at Bob Mizer’s studio. Mizer was a lifelong resident of his mother’s house at the western edge of downtown LA. He began to produce more explicit and pornographic work after her death in 1964, which loosely coincided with an easing of legal restrictions around male nudity in print. Several of Mizer’s models lived in the compound he built up around his mother’s building once he took over ownership.18 Hockney’s paintings and Mizer’s publications served as propaganda, demonstrating, according to the painter, “something [he] felt hadn’t been propagandized as a subject: homosexuality.”19 For both Mizer and Hockney, the pool was a critical site for the representation of queer life at the scale of the everyday, and more intimately so when that pool was framed by the privacy of the domestic realm.

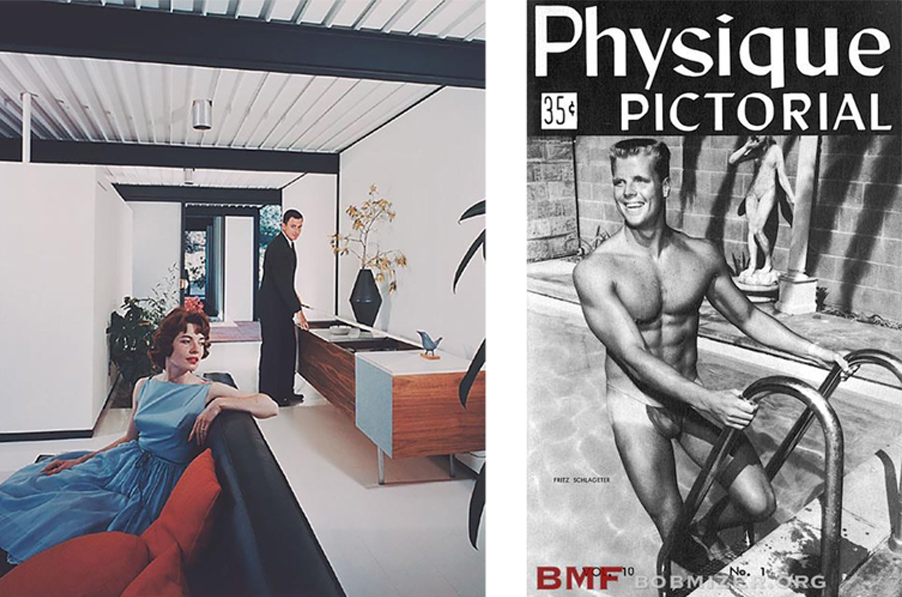

Julius Shulman, photographer of many of LA’s Case Study Houses, including the Koenig one that drew Hockney to California, was among the first of his generation to include people in his images, using architecture to stage a theater of domesticity. A couple sits down to eat while children play ping-pong (Mirman Residence); a woman sits on a couch in a blue dress while her suited husband puts a record on (Bailey House); a couple enjoy a cocktail poolside while a friend surveys the land beyond through a pair of binoculars (Stahl House). 20

In Daddy, the house sets up a performance of domestic uncertainty. Franklin’s friends, gallerist, mother, and studio all come to occupy its open plan and perform other rituals of domesticity: the consumption of prescription pills, the ordering of delivery, and after-partying, mostly on Daddy’s dime. Max, Franklin’s friend, “looks great in a swimsuit” and unsurprisingly tans poolside in a Speedo, not unlike one of Mizer’s models.21 This is all mostly fine until Mom shows up. The dynamic between Andre and Franklin becomes increasingly tenuous as the latter retreats into a childlike state over the play’s course.

The ease with which the villa over-accommodates its inhabitants’ needs and desires—the very openness of its plan, transparency of its boundaries, and provision for leisure—is perhaps partly to blame for their increasingly fractious encounters. The modernist villa has a long tradition as a misanthropic actor in works of fiction, tangling up the relationships of those therein, and this history is hard to un-see in Harris’s play. Films like Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle (1958) and Blake Edwards’s The Party (1968) take a slapstick approach to the theme, but there’s truth to the fiction. Rudolph Schindler’s Kings Road House in West Hollywood was the site of one such entanglement: “…the Kings Road house in 1925 was the center of L.A. cool. It was a sweetly decadent life. Idealism, art, outrage, music, and manifestos filled the warm, fragrant nights,” as Mitch Glazer put it in a 1999 piece for Vanity Fair. Though of an earlier modernist style than the Case Study Houses of the forties and fifties, a visitor is struck by the lack of partition and the dissolution of any notion of continuous perimeter. Dione Neutra, wife of the architect Richard and guest of the Schindlers, remarked in a letter that while living there, she had “never heard so much talk about broken marriages and nervous breakdowns.”22

Benjamin Critton’s 2010 zine, Evil People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films, sums up today’s version of the same sentiment: modernist house as emblem of mistrust. Hockney’s California scenes around sky-blue swimming pools and art-laden villas are often haunted by a pervading sense of loneliness and quiet discord, laden here and there with the iconographic markers of lovers past. Like Harris’s play, the figures in Hockney’s paintings were sometimes brought together from distant origins. He famously credits the composition of Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) to the chance encounter of two photographs on his studio floor.23 Eventually, the painting was completed with the help of preparatory photographs taken in the South of France, London, and Hollywood in a sleight of geo-pictorial collapse.

Hockney’s painting of an ordinary, queer domestic life in California began before he had even arrived in 1964. In 1963 he finished Domestic Scene, Los Angeles in England, picturing a boy assisting in the bathing of another man under the jet of a shower—particularly poignant given that homosexuality was still illegal in England at the time. Harris’s play problematizes a similar condition: the need to leave home to attain the home life one desires. And yet, the aspirational Bel Air doesn’t entirely satisfy.

In turning the audience’s backs to the city at large, looking into the home instead, Harris adopts the gaze of Hockney, queering the domesticity on offer and questioning the colonial vision of the westward prospect. Instead of the ocean, we’re given the saltwater pool, technologically calibrated to the temperature of the Pacific.24 The American territorial expanse, cunningly refocused by the viewfinder enclosure of the modernist frame, is here re-presented in open plan, yielding no cover from confrontation, incapable of providing any distance between those who live inside.

-

Jeremy O. Harris, Daddy, Act 1, Scene 1. ↩

-

In a text message with the author, Harris stated, “it’s more like distorted self-portraiture” (February 10, 2019, 8:23 p.m.). Harris points to Hockney’s influence in Daddy, Playwright’s Notes. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) is currently the most expensive artwork by a living artist ever sold. It set the record at an auction of Postwar and Contemporary Art organized by Christie’s in New York, on the 15th of November, 2018, where it sold to an anonymous bidder for 90,312,500 USD. “Hockney Masterpiece Breaks World Record in New York,” Christie’s, November 16, 2018, link. ↩

-

In a phone call with the author, Matt Saunders revealed that in 2018 he designed another theatrical set modeled on a midcentury modernist house for the Guthrie Theater’s production of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? With Daddy, he examined a number of Hockney paintings and photos of Case Study Houses, including those of Pierre Koenig. He mentioned that for this staging, the house’s construction date would be left ambiguous: it could be a midcentury villa or a contemporary imitator. ↩

-

Harris is in his final year at the Yale School of Drama. In the past, he has credited this script with having clinched his spot in the Ivy League. “I used to say, ‘Daddy got me into Yale,’ or ‘Daddy got me into MacDowell Colony,’ because I don’t have nepotism. I had to write my own daddy into existence, and it ended up working out in a meta way.” Mark Guiducci, “Jeremy O. Harris Wrote His Own Daddy into Existence,” Garage Magazine, issue 16, February 5, 2019, link. Jesse Green, theater critic for the New York Times, described Slave Play as “willfully provocative, gaudily transgressive, and altogether staggering.” Jesse Green, “Review: Race and Sex in Plantation America in Slave Play,” the New York Times, December 9, 2018, link.

↩ -

“David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures),” Postwar and Contemporary Art, Auction Preview, Christie’s, December 12, 2018, link. ↩

-

“Executive Orders Disposition Tables,” Federal Register, National Archives, August 15, 2016, link. ↩

-

“Our History,” President’s Council on Sport, Fitness, and Nutrition, March 13, 2018, link. ↩

-

John F. Kennedy, “The Soft American,” Sports Illustrated, December 26, 1960, 14–23, link. ↩

-

For instance, Bob Mizer’s Military Films, aka Story Film Classics: New Recruit, AMG, 1958–1971. ↩

-

Hans Hollein, MAN transFORMS: An International Exhibition on Aspects of Design, Conceived by Hans Hollein and Sponsored by The Johnson Wax Company, for the Opening of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Design, Cooper Hewitt Museum (New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1976). ↩

-

Harris, Daddy, Act 1, Scene 3. ↩

-

“Franklin lays by the pool with MAX and BELLAMY. He is wearing the same Speedo as before, he now has on a pair of brand-new CELINE sunglasses. They are passing a vial of cocaine back and forth throughout as they drink mimosas.” —Harris, Daddy, Act 1, Scene 2.

MAX

Bellamy just told me she’s in love

with a guy she met on

DaddyFinder.com.

That’s too much.

BELLAMY

I didn’t say

I was / in love.

MAX

And you!

Too much!

(he points to the movers)

You’re fucking moving in

with your sugar daddy / after like...

FRANKLIN

Just my studio.

He’s not my “sugar daddy”—

the fuck, Max?

I couldn’t afford—

and

God!

He offered/

to let me have the...[^14] -

This is one of two introductory quotations to set the mood before launching into Act 1. The other is from Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda”: “He live in a palace, bought me Alexander McQueen he was keeping me stylish…I’m high as hell, I only took a half a pill. I’m on some dumb shit,” Harris, Daddy, Playwright’s Notes. ↩

-

Harris, Daddy, Playwright’s Notes. ↩

-

Quoting 2 Timothy 3:4–5, New King James Bible. Harris, Daddy, Act 2, Scene 1. ↩

-

Harris adds that his visualization of the play was complemented by a soundtrack that included “a lot of George Michael, Nicki Minaj, and Shirley Caesar while writing,” Harris, Daddy, Playwright’s Notes. ↩

-

“‘Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool,’ David Hockney, 1966,” Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool, last modified 2019, link. ↩

-

“Mizer Compound at Center of Photographer’s Empire,” Bob Mizer Foundation, January 5, 2016, link. ↩

-

“‘Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool.’” ↩

-

David Basulto, “Julius Shulman (1910–2009),” Archdaily, July 17, 2009, link. ↩

-

Harris, Daddy, Playwright’s Notes. ↩

-

Mitch Glazer, “Genius and Jealousy,” Vanity Fair, April 1999, link. ↩

-

“David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist.” ↩

-

“BELLAMY: It’s temperature controlled. During the day it like, should be whatever the like temperature of the ocean is. / MAX: Yeah, it feels normal to me. / ZORA: This feels normal?” —Harris, Daddy, Act 2, Scene 3.

Daddy runs from February 13 to March 31 in New York, co-presented by the Vineyard Theatre and the New Group. It is directed by Danya Taymor and stars Carrie Compere, Alan Cumming, Tommy Dorfman, Kahyun Kim, Denise Manning, Hari Nef, Onyie Nwachukwu, Ronald Peet, and Charlayne Woodard. Set design for Daddy is by Matt Saunders. Research for this text by Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado. ↩

Miles Gertler is co-director of Common Accounts, an office for design inquiry that examines intersections of architecture with the body, cultures of the internet, and other tools for city building. He is based in Toronto, where he teaches at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design.