Have you heard of North American Airlines, Miami Air International, Omni Air International, or World Airways? Perhaps, but likely not. Half are now defunct, but all existed in the past decade as charter airlines shuttling a range of individuals including cruise-ship passengers, professional athletes, film crews, humanitarian relief staff, and—with approval from the US Department of Defense—military personnel on national and international charter flights. Their irregular schedules and destinations, as well as the specific intent of their routes, mark these flights as near parallels to mainline carriers. Omni Air International maintains the familiar features of an airline: a plane fleet, pilots, and flight attendants. But their operations outside of ordinary terminals and gates hints at a shadow system that functions just outside the awareness of most air travelers sitting on commercial flights each day. That’s presumably the way they like it. All of the airlines listed above have had planes land at Shannon Airport in County Clare in western Ireland with members of the US military—as well as small arms, explosives, and other equipment—on board making the journey between the United States and military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other locations. Because these charter airlines are or were nominally civil carriers, their regulation and inspection is handled by the Irish Department of Transport, Tourism, and Sport, just like a normal commercial airline, rather than the Irish Department of Defence, in spite of the troops and weapons on board.

It is not the United States but Ireland where these airlines have experienced negative publicity for their operations. After September 11, 2001, the Irish government offered the use of Shannon Airport to the US government for military operations. Since 1986 the airport has been a location of another kind of American space—travelers to the United States from Shannon, as in about a dozen other, mostly Canadian, airports undergo US border preclearance, thus avoiding the need to go through immigration and customs upon arrival in a US airport. In response to the post-2001 military presence, Irish residents have staged protests at Shannon and proclaimed that the use of the airport by the US military violates Ireland’s principle of neutrality outlined in its constitution. American military flights stopped in early 2003 because protesters repeatedly breached the airport’s boundaries and hangars to attack aircraft with paint, hatchets, and hangers in order to prevent planes from flying.1 But this was only a temporary suspension. In 2005, some nine hundred American soldiers passed through Shannon every day. The Guardian reported that packs of soldiers in desert fatigues could regularly be seen shopping at duty-free counters on their transit between the United States and Iraq.2 By late 2015 an estimated 2.5 million US troops had stopped by Shannon.

The territorial and bureaucratic slippages that made these flights possible in Shannon are common throughout the globe. Journalists and scholars in architecture and other fields have mined the contours of these borders, across which the activities of state, military, and corporate power are facilitated.3 Dispersed among a variety of jurisdictions, entities, and sub-entities, often in carved-out spaces undifferentiated from their surroundings or appearing as mundane as a storage facility, they can be difficult to identify. The scale of these activities ranges from moving works of art—or, for that matter, corporate earnings—as a means of avoiding taxes to transporting prisoners.4 Notably, such sites often reveal few perceptible traces of anything truly amiss. After all, travelers flying internationally experience these zones when they go through duty-free shops, an entity that began at Shannon Airport.

Once called Rineanna, Shannon Airport and its adjacent town developed as a stopover in the 1940s for wealthy travelers in a time when planes needed a place to refuel between North America and Europe. But advances in airplane technologies soon removed the need for a stop in Ireland, producing the fear that Shannon’s days with a bustling airport would soon end. In the face of a forecasted loss of Shannon Airport and population declines due to emigration after 1945, the Irish government implemented measures to encourage foreign investment as a path toward economic growth. The passage of the Customs Free Act by the Dáil, the Irish parliament, in 1947 paved the way for a former restaurant manager and caterer named Brendan O’Regan to reserve a portion of the airport building as a customs-free area to establish the world’s first duty-free shop at Shannon to continue attracting planes and their passengers to the airport with the promise of customs-free goods, especially alcohol and cigarettes.5 These programs ushered the creation of a new spatial domain, a Special Economic Zone (SEZ), one more or less indistinguishable from the territory outside of its borders at the time of their formation. Yet these zones have become vital conduits for constructing and maintaining economic development and trade across the globe. And it all, so the story goes, began in Shannon.6

Extending his reach just beyond the airport, O’Regan assisted in setting up the Shannon Free Zone near the airport to attract foreign companies to the region in a territory within Ireland yet unencumbered by the nation’s usual taxes and regulations. Tax incentives and research and development grants produced additional attractions to the area. Companies including the diamond merchants DeBeers, Intel, GE, and Lufthansa set up subsidiaries in the Free Zone.7 Today Shannon’s population hovers around ten thousand, much smaller than one would expect from a town with an airport where 1.8 million people flew through in 2018. Nevertheless, on visits to Ireland, Chinese premiers Wen Jiabao and Xi Jinping both made pilgrimages to Shannon to see the place that began the Special Economic Zone model that they believe catalyzed China’s growth.

The Irish artists Gareth Kennedy and Sarah Browne, who formed a Dublin-based collaboration, Kennedy Browne, in 2005, have spent much of their career investigating such seemingly banal sites of consequence in the development of modern global capitalism and their by-products. A retrospective titled The Special Relationship at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign earlier this year by curator Amy Powell, curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the museum, brought together six pieces created over the last decade that sought, in their words, to “address the supposedly eternal narrative of neoliberal capitalism as a fiction.”8 With work heavily based on the detritus and remnants of business literature, blogs, and legal proceedings, this first survey of their work in the United States emphasizes their process of denaturalizing stories of the world’s post–Bretton Woods order. This often simply means taking the tools of that order and presenting them in many cases almost as-found. The modifications Kennedy Browne make in their process of collecting and reorganizing the ephemera, locations, technologies, and products of everyday encounters with free-market capitalism puts into relief the received assumptions that have sustained those narratives over time and imbued them with authority. The final products they present underscore the convoluted logics and rationalizations that have been used to justify our current economic status, as well as the loopholes and spaces just outside of regulatory authority that have made such conditions possible. Moreover, by making visible the collaborations between state institutions and corporate interests, their work begins to lift the veil of secrecy and anonymity that undergird those processes and show their human consequences.

In almost all of the works in the exhibition, the centerpiece is a video consisting of a reenactment or stock footage, usually presented on flat screens. Displayed off to the sides are associated objects including photographs, a pill, a stack of papers under a piece of obsidian, and in the case of The Myth of Many in One (2012), a rocking horse, a dismantled crib, and books about Napoleon that represent emblematic objects in the childhood formation of Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and other entrepreneurs. The overall effect is spare. On closer inspection the seemingly unexceptional objects on display suggest the deeper stories behind their presence.

Take, for example, a work that consists of forty-two pieces of paper hanging on one wall. Milton Friedman and the Wonder of the Free Market Pencil from 2009, one of the earliest created pieces in the retrospective, centers on a moral tale written and told by Friedman on the 1980 series Free to Choose that aired on PBS. Free to Choose, a ten-episode series and an associated book written with his wife, Rose, was Friedman’s paean to his faith in the benevolent relationship between human and economic freedom broadcast on a publicly funded station. Based on a 1958 text called “I, Pencil” by Leonard Read, an economist and associate of Ayn Rand, in this parable Friedman outlined the necessary resources, people, and actions of putting together a simple pencil—a microcosm for illustrating the alluring capacities of the global free market and its ability to bring lasting peace. Kennedy Browne unsettle this narrative through one of the tools meant to reinforce the parable. Each of the forty-two pieces of paper contains the parable’s text in a different language. Rather than a human translation, Kennedy Browne instead fed the story into Google Translate beginning with English, then followed by forty additional languages in alphabetical order with each translation based on the previous, like a linguistic peregrination. The final page is a retranslation back into English. Only now it is a much shorter and much less comprehensible version of the parable. The moral of the story, thus, gets lost in translations.

Kennedy Browne use Ireland, a nation with a population of less than five million and a land area comparable to a Midwestern state, as a vital setting for the global dynamics and narratives they portray. Its strategic position “between Boston and Berlin,” in the words of Irish politicians, frames the group’s objective to present new perspectives between Ireland and the United States in their work. Sometimes Ireland figures in an understated way—Google’s European, Middle Eastern, and African headquarters is in Dublin and figures in 167 (2009), a video that combines Google’s presence with Friedman’s pencil. The number references the number of languages spoken in the Irish capital. Values in Action from 2011 consists of two boarding passes issued to Kennedy and Browne, who were passengers on the flight, and photographs of the plane for the very last nonstop Ryanair flight from Shannon to Lodz, Poland, a flight that was discontinued with the closure of a computer factory in Ireland. In an ironic denouement, the computer factory was relocated to Lodz.

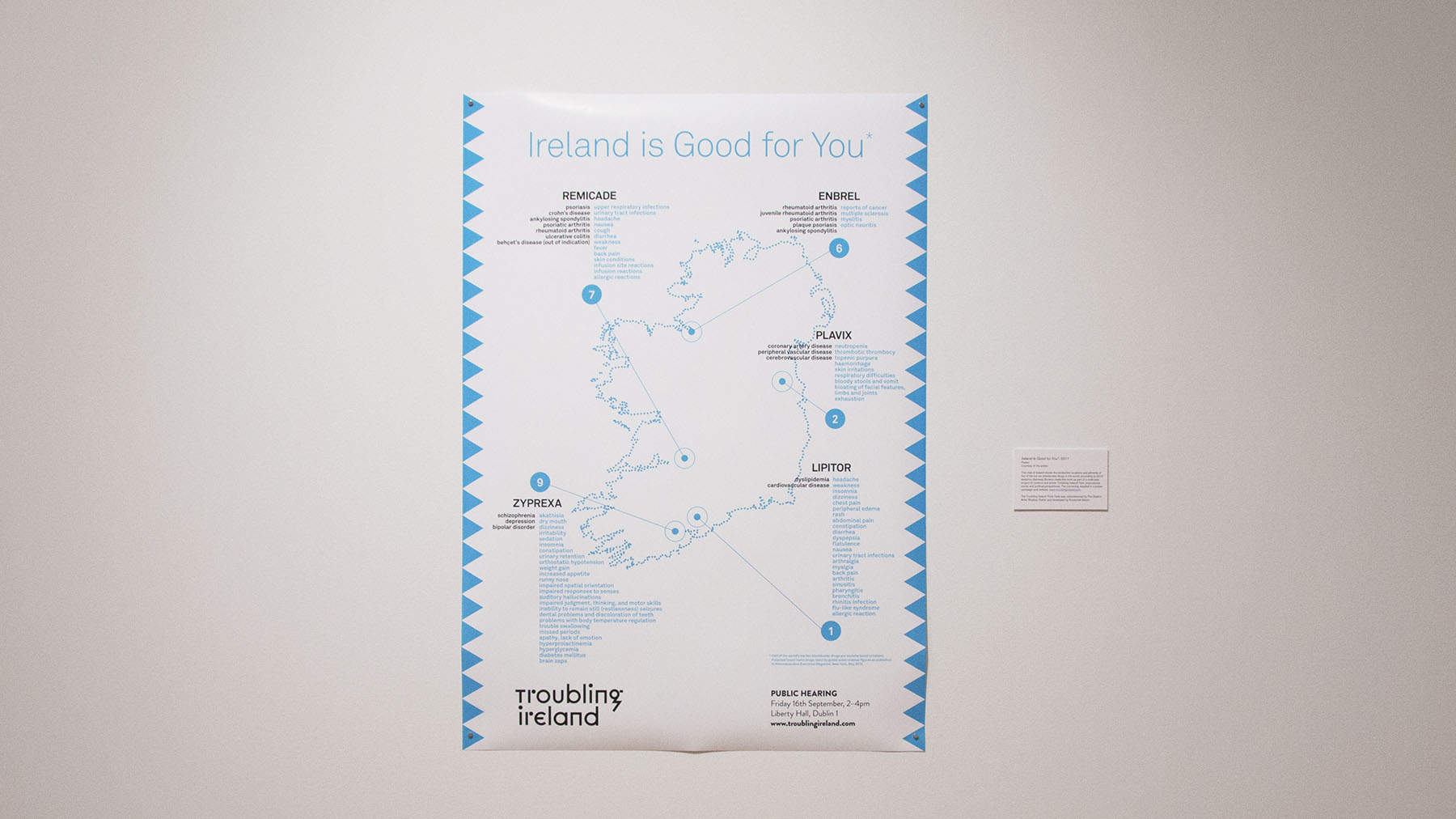

The story of Shannon Airport’s ascendancy and influence comes into central focus in the exhibition’s eponymous piece. The Special Relationship consists of a grouping of three associated works initially produced as individual pieces. The first is a four-minute long video of still photographs with an audio track. A few feet away is a single pill enclosed in a display case. On an adjacent wall hangs a map of Ireland with “Ireland Is Good for You*” emblazoned across the top. Together these objects make up a conceptual rather than formal triptych linked by foreign—mostly American—interests in Ireland’s human resources and territory.

The pill and the poster reference the importance of the pharmaceutical industry in Ireland’s economic development. In the 1960s Irish economic interests set their sights on the international pharmaceutical industry as a prime source for investment. Today more than 250 (including thirteen out of the largest fifteen) pharmaceutical companies manufacture drugs and have research and development arms in Ireland, making the nation the largest exporter of pharmaceuticals in Europe and the seventh largest in the world.9 Pharmaceutical production makes up one third of the total value of products sold in the Irish economy. This is buttressed by favorable tax rates, a strong infrastructure, including easy access to the rest of Europe, and a young, English-speaking workforce. The relationship between state generosity toward corporations in Ireland isn’t always so smooth—in 2016 the European Union fined Apple €13 billion for avoiding paying taxes due to a deal between the company and Irish tax authorities that allowed the company to pay at maximum a 1 percent tax rate rather than the usual Irish corporation tax of 12.5 percent.10

The rise of the Irish pharmaceutical industry also provides a smooth narrative of transformation of a nation from a sleepy place where the primary economic motors were agriculture and fishing to a modern, industrial economy. Pfizer started in Ireland as a humble producer of citric acid for soft drinks, and Eli Lilly began their tenure by purchasing a rural farm. A Lilly advertisement in a trade publication in 2013 features an aerial photograph of their manufacturing facility in Kinsale in County Cork, surrounded almost exclusively by enclosed fields, and tens of thousands of residents work in drug manufacturing in rural parts of the country.

In Kennedy Browne’s map of Ireland that announces “Ireland Is Good for You*,” spots on the map point not to specific cities but locations of pharmaceutical plants. A dot south of Dublin is labeled “Plavix,” a drug to treat individuals at risk of heart disease or stroke. Two columns beneath the label outline prescribed and off-label uses followed by a generally longer list of the variety of side effects. The Eli Lilly plant near Cork produces Zyprexa, used to treat schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder. The list of the drug’s side effects runs to twenty-five items including dry mouth, impaired spatial orientation, diabetes, and “brain zaps.” Numbers corresponding to each location point to the fact that in 2010 a pharmaceutical trade journal announced that five out of the top ten drugs based on global sales revenue were manufactured in Ireland, including the top two (Lipitor, now out of patent, and Plavix).11 Pfizer now produces the active ingredient for Viagra in Cork.

A single pill in the display case near the map, titled Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, is an anti-psychotic pill manufactured in Ireland. The solitary display hinges between the map and the video display of photographs created in 2013 as The Special Relationship. For four minutes the display cycles through photographs of mainly charter aircraft from Omni Air International and World Airways, among others, that are used to ferry US military personnel taking off, landing, or standing at Shannon Airport between October 2001 and October 2013. Rather than taking the images themselves or sourcing images from anti-US military activists, Kennedy Browne sought permissions from an aviation photo website based in Ireland. Out of 117 requested images taken by twenty photographers, seven photographers of forty-two images granted permission, while six photographers of thirty-seven images explicitly denied permission. As the series of images progresses, a woman’s voice reads a list of interview questions adapted from a seventeen-point PTSD Symptom Scale developed in 1993. Questions such as “Have you had recurrent or intrusive distressing thoughts or recollections about the event?” or “Have you had persistent difficulty concentrating?” connect the experience and trauma of a continuous war on terror with attempts at its treatment, as well as the ongoing emphasis on economic development through foreign investment.

Part of the Irish context that The Special Relationship indexes is the supposed economic advantages of opening Shannon Airport to the US military. Local politicians have argued that those residents opposed to American presence cared little about local jobs and the sustained growth of the Celtic Tiger, while opponents asserted that Shannon is in practical terms a US military base and more gravely a stopover for numerous suspected CIA extraordinary rendition flights.12 An activist group called Shannonwatch keeps a list of flights they believe have been used for extraordinary rendition, including up to fifty that have landed at Shannon.13 The supposed birthplace of the rules to circumvent the taxes and regulations tied to a territory to allow tourists to buy tax-free alcohol is now implicated for facilitating extrajudicial torture perhaps on planes flying under the authority of the Irish Department of Transport, Tourism, and Sport.

The ordinary and readily available remnants of corporate activity, bureaucratic procedures, stock photographs, and technologies coupled with willful ignorance or lack of oversight are the material out of which Kennedy Browne produce their narratives, bringing the abstract parts of geopolitical strategies and neoliberal capitalism closer to our day-to-day activities and suggesting how they structure our own experiences. Presented within sites and scales we encounter regularly—discount airlines, pharmaceuticals, Google Translate, Apple products, and social media—but with a perspective that skews away from intended uses and expected outcomes, we can begin to see the absurdities—but also make sense—of the long-standing assumptions and myths that have governed our lives, and attempt to envision a new story.

-

Brian Lavery, “Ireland: Airport Is Shunned,” the New York Times, March 1, 2003, link. ↩

-

Angelique Chrisafis, “Concerns Grow in Ireland over Use of Shannon Airport as US Military Stopover,” the Guardian, January 21, 2006, link. ↩

-

See for example: Jordan Carver, Spaces of Disappearance: The Architecture of Extraordinary Rendition (New York: Urban Research, 2018); Stephen Grey, Ghost Plane: The True Story of the CIA Torture Program (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006); “Mapping Ghosts: Visible Collective Talks to Trevor Paglen,” in An Atlas of Radical Cartography, ed. Lize Mogel and Alexis Bhagat (Los Angeles: Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Press, 2007); Nicholas Shaxon, Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001); as well as Keller Easterling’s books Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and Its Political Masquerades (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005) and Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (New York: Verso, 2014). ↩

-

David Segal, “Swiss Freeports Are Home for a Growing Treasury of Art,” the New York Times, July 21, 2012, link; Daniel Grant, “As Art Collections Grow, So Do the Places that Stash Them,” the New York Times, November 13, 2018, link. ↩

-

Brian Callanan, Ireland’s Shannon Story: Leaders, Visions, and Networks: A Case Study of Local and Regional Development (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2000), 41–119. ↩

-

Historian Vanessa Ogle notes that foreign trade zones actually first appeared in Puerto Rico in 1947, followed by Panama in 1948 and Shannon in 1959. These zones lured investors with lightly regulated labor, the absence of unions, tax holidays, and little environmental regulation. Vanessa Ogle, “Archipelago Capitalism: Tax Havens, Offshore Money, and the State, 1950s–1970s,” American Historical Review (December 2017): 1,455. ↩

-

Matt Kennard and Clare Provost, “Shannon—A Tiny Irish Town Inspires China’s Economic Boom,” the Guardian, April 19, 2016, link. ↩

-

“Ireland: Playing to Win,” Pharmaceutical Executive (March 2017), S2. ↩

-

Sean Farrell and Henry McDonald, “Apple Ordered to Pay €13 billion after EU Rules Ireland Broke State Aid Laws,” the Guardian, August 30, 2016, link. ↩

-

The number switched to six. Fiona Reddan, “Made in Ireland: Viagra and Botox, Claritin and Panadol,” the Irish Times, November 28, 2015, link. ↩

-

Gordon Deegan, “Security Expert Tells Trial Use of Shannon Is Essential to US Military,” the Irish Times, February 24, 2015, link. ↩

-

See Shannonwatch’s website, link. In the United States, a similar group is North Carolina Stop Torture Now, link. ↩

Pollyanna Rhee is the 2018–2020 Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral fellow in environmental humanities with the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In fall 2020 she will join the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois as assistant professor of landscape history.