The Island

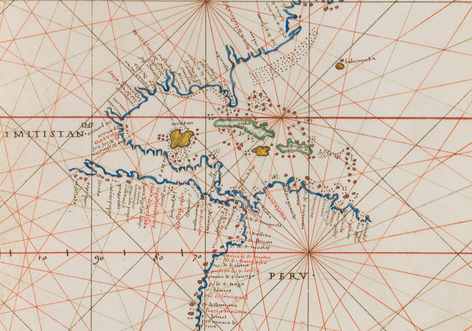

In 1546, the Genovese cartographer Battista Agnese depicted the Yucatan Peninsula as an island separate from mainland America. As if a continuation of the Caribbean archipelago, the island’s actual connection to the continental terra firma is misinterpreted as shoals. Not meant for navigation, Agnese’s portolan atlases—of which this particular geographical fallacy is a part—served as speculative testimonies of a world emerging from the eyes of colonizers, translated for the consumption of dignitaries and aristocrats across Europe. Like so many maps attempting to claim a “newly” explored territory, the Yucatan inaccuracy is not surprising. For the colonizer, the incompleteness of both knowledge and the accounting of resources seem to go hand in hand—the island of “Iucatan” was preemptively gilded, perhaps, to signal its extractive potential. And, yet, this erroneous representation of the peninsula as an island resonates today, somehow, with the language of modernization embraced by the current federal government in Mexico, which has presented the country’s southeast as an economic island—impoverished, disconnected, and abandoned in national plans of development. For Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the current Mexican president (known colloquially as AMLO), the disparity between national economic ambitions and the economic realities of the southeast has become intolerable, a walking contradiction: “this region is the richest of Mexico [in terms of resources] inhabited by the poorest.”1 Determined to close these gaps, AMLO has set in motion a series of large-scale infrastructural projects that promise to integrate the southeast into wider networks of national and global tourism and economic “diversification.” Yet the “good” intentions of the federal government risk reproducing the colonial optics of Battista Agnese. For how could these techno-developmentalist goals—goals defined by what this region “lacks”—possibly account for the ambitions of indigenous people in the southeast, who perhaps do not see economic separation as a lack but as a potential to exercise their right to self-determination and to live outside Western metrics of development.

Five centuries after Agnese, Mexico’s southeast region continues to be seen as a promised land that must be mapped, accounted for, and developed according to the interests of those seeing it from the outside. And while access to infrastructure appears distant from colonial strategies of domination, this claim toward integration via modernization subsumes alternative forms of life, incorporating humans and nonhuman actors into larger capitalist relations of extraction while continuously racializing and dispossessing those bodies toward these ends. Within the neoliberal horizon of state practices, the emergence of tourism infrastructures cannot be disentangled from wider processes of capital extraction, nor can it be disentangled from the long and complex history of making and remaking the Mexican southeast for the enjoyment of those outside it.

The goal of this essay is not to compare these two historical moments but rather to question whether this infrastructure-driven development perpetuates a colonial legacy that integrates a given territory (as a remedy for its presumed isolation) only to facilitate the future extraction and accumulation of capital, nonetheless preserving the racial inequalities that separated them in the first place. In the words of A. M. Babu, recalling the work of Walter Rodney, a question arises in the redrawing of such cartographies—whether the imposition of standards of economic development “is the cause, and not a solution, to economic backwardness.”2

The Line

Among the infrastructural projects attempting to “integrate” Mexico’s southeast into the political-economic plan of the federal government is the Tren Maya. The megaproject proposes to unite and interconnect five southern states—Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Campeche, Tabasco, and Chiapas—with a 1,500-kilometer train line. Driving the project is AMLO’s ambition to “detonate” the region’s tourism industry, stimulating a host of new jobs in the area. If completed, the line would link the existing tourism market on the coast—Cancun, Tulum, Playa del Carmen, etc.—with prominent inland Mayan archaeological sites and urban centers, passing through major protected ecological reserves and indigenous and communal lands, or ejidos.3 Breaking with his predecessors, AMLO insists that his administration will work with indigenous communities and will be conscious about the environmental impact of the train.4 But while the project was officially inaugurated in December 2018, the details and the president’s promises—the exact route, the budget, the role of private and foreign investment, the environmental impact, and the sociopolitical consequences to indigenous communities—remain to be seen.5

While for AMLO the train is an “act of justice for the southeast,” in the eyes of Subcomandante Moisés—current spokesman of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN)—the train is a “project of destruction.”6 Zapatistas, as they are colloquially known, have been in the public eye since 1994. Organizing from the remote Sierra Lacandona in Chiapas, the Zapatistas are a militant group that, in their advocacy for indigenous rights, have captured the imagination and solidarity of many indigenous communities throughout Mexico and beyond. They share an ideological alliance with their namesake Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919), a leader of the Mexican Revolution of 1910 that mobilized the rural south against the oppression of large landowners (latifundistas).7 Yet, EZLN not only embrace Zapata’s cry for “land and freedom,” but they also situate their agrarian struggle in a larger historical portrait of centuries of dispossession:

With these words, Subcomandante Marcos, the first spokesman of EZLN, describes not only a distant struggle but also the perpetuation of colonial legacies for the indigenous peoples in the present. For the Zapatistas today, Tren Maya’s destructive force is part of this history. They have recently argued that the State has failed to consult indigenous communities affected by Tren Maya and has disregarded the wider spatio-political implications of the project.8 Indeed, the ambitions of the train have not been mapped in relation to the contestations that already exist within indigenous communities (privatization of common lands, shortage of social infrastructures, institutional racism) as well as to those it is likely to foment (cultural appropriations, global investment interests, etc.). For example, according to the current Mexican secretary of tourism, it is expected that the train will bring an additional four million tourists to the region each year.9 Yet little has been said about the pressures that this influx of transient people will add to water systems, to waste management, to traditional forms of agricultural production, to ecological diversity, to the resources of the region, to migration, to communal lands, and, among all, to indigenous modes of existence. We know very well that in advanced capitalist nations, infrastructure at this scale never materializes delicately but rather invasively—through the redistribution of resources, the re-articulation of landownership, and the total disruption of ways of life.10 As anthropologist Tania Murray Li argues, behind the good intentions that normally accompany this type of development, the turn to infrastructure risks “rendering technical” the social and political struggles that preempt development in the first place and that often are exacerbated by development itself.11 And thus, as Murray Li states, “Questions that are rendered technical are simultaneously rendered nonpolitical.”12 In doing this, Tren Maya’s homogenous treatment of the region not only depoliticizes the ongoing struggles of indigenous peoples, but it also seems to reinstitute a colonial legacy undermining centuries-long struggles for political autonomy from the State.

For Murray Li, development strategies are often predicated on the skewed and incomplete diagnosis of a community that tends to identify that community as deficient based on the technical biases of “experts.” This form of technical diagnosis not only fails to understand the conditions that impoverish a people in the first place, but it sets the stage for development and dictates its scope. This is no different for the Tren Maya. If there is a diagnosis motivating the project, it is that the region has been deemed economically isolated from the goals of the national economy—that Yucatan is an island once again. Without including the voices of indigenous Mayan peoples, none of this speaks on their behalf; it simply marks them as subjects to be improved under generic technical terms. So far, the current administration has failed to properly consult local indigenous communities. This is a core violation of international indigenous rights—from those stipulated in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization to those declared by the United Nations in the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Though still revealing the asymmetry of developmentalism that is rife in global governance, the latter proclaims, “States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples…in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories….”13 In the absence of this consultation, the leadership behind Tren Maya has instead chosen to continue a recent history of development that sees “eco-tourism” as self-evidently redemptive, as a cure that promises to penetrate isolated localities and to draw them into a global market of conscientious tourism. It seems Tren Maya’s relational telos aims to, at last, correct Battista’s misrepresentation of Yucatan as an island. Yet in turning a deaf ear to the knowledge of indigenous communities, Tren Maya becomes a tool for subsuming the many livelihoods of the southeast to the will of the state. And, more importantly, the train becomes a device for seeing indigenous bodies as a “property of enjoyment”—racially separated from those who define their value and thus commodify the cultural difference between themselves and the ruling minority.14 As Kathryn Yusoff argues, this extraction of value “transmutes those subjects through a material and color economy that is organized as ontologically different from the human (who is accorded agency in the pursuits of rights, freedom and property.”15 In denying indigenous peoples the right of consultation, the Tren Maya, as it stands today, only enables and reinstates the optics of othering.

The turn to eco-tourism in the region gained momentum in the late 1980s under the presidency of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (between 1988 and 1994). This is the same administration that ratified the NAFTA deal, setting in motion the neoliberalization of the Mexican economy. Salinas formalized the so-called Ruta Maya, an initiative of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras in the late ’80s to encourage environmental and culturally oriented tourism across the Mayan territories.16 The strategy was seen not only as a tool to smooth political differences between these countries but also as a “non-destructive development to provide jobs and money to help pay for preservation.”17 The sentiment of this period was perhaps most concretely captured and made visible by the October issue of National Geographic in 1989, which presented “Ruta Maya” to its potential consumers in a piece by editor Wilbur E. Garrett.18 Alongside colorful images of people, places, beaches, rainbows, and tropical shoals, Garrett described the region with an array of culturally recognizable references for his Western (read American) audience. In the words of Garrett, the “Mayan world” had become “the Serengeti of the New World,” and the exuberance of the rain forest was compared to Gothic cathedrals.19 This world was, for Garrett, (luckily) far from “the fearsome, snake-infested saunas that only an Indiana Jones could love”; it was instead an “ecological cornucopia” ready to be enjoyed.20 The cultural markers throughout Garrett’s piece narrate an exotic yet tourist-friendly region but one that is also on the verge of destruction: “rainforests are falling at an alarming rate, because their timber provides quick cash, and cleared forests become coveted farms for the growing masses of poor people who live near most tropical forests.”21 This tone continues throughout the piece—the peoples of Yucatan are described as incapable of caring for their own lands. While perhaps in cruder terms than development experts, Garrett nonetheless articulates this community’s need for improvement. And thus, his piece takes on a second function: to mobilize this imaginary in a call for intervention through eco-tourism.

This imaginary of development is reinforced by a painting included in (and presumably commissioned for) the article by John C. Berkey—a science fiction artist best known for his illustrations of the original Star Wars. Typical of Berkey’s work, the painting presents a rain forest that is at once hyperrealistic and dreamlike. Lavish vegetation immerses the viewer in a world where scarlet macaws fly freely and ancient pyramids are untouched and overtaken by tropical plants. Cutting across the scene is a monorail that, despite its passage through a slight clearing in the forest, avoids becoming the painting’s central protagonist. While, its supportive poles and cables—the infra of the structure—blend with the background, the monorail car’s visual dominance is decentered, appearing like a floating hut. This orientalist attempt to camouflage the actual infrastructure by lightly suspending it above the jungle floor creates a horizon of expectations that naturalizes the presence of the tourist and the benevolence of infrastructure. This is precisely the image that Garrett wanted to cultivate in what he described as “making some forests into living theme parks.”22 Perhaps this is the first imaginary of Tren Maya.

While this narrative of Ruta Maya might not be surprising in the context of a magazine that has a track record of racist coverage and of constructing and commodifying stereotypes, it is surprising that Garrett’s narrative became the ideological backbone that stimulated a much larger project in the years following its publication.23 In 1990, the seeds of this project manifested in a small donation by the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) that was interested in designing investment plans for the touristic development of “Mundo Maya.”24 In a parallel move in 1991, Salinas de Gortari proposed a crucial reform to agrarian land that would radically transform the rural landscape in Mexico in years to come. By 1992, this reform was concretized by sweeping amendments to Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution—an article that has historically guaranteed the institution of the ejido, or a communally managed piece of land. The reform allowed ejidos to radically shift from usufructuary rights to full ownership rights. In broad brushstrokes, it provided the ejido holders the legal capacity to rent, sell, subdivide, or mortgage their land parcels for the first time in recent history. In almost two decades, the reform of 1992 has radically transformed the rural outskirts of many urban centers. Left to the market, many ejidos have been absorbed by sprawling cities driven by cycles of real estate speculation and unregulated urban development. More than signaling the privatization of common lands, the reform of 1992 marked a radical regression to the agrarian reforms set in motion during the Mexican Revolution that culminated in the victorious enactment of the ejido system as a constitutional right in 1917. Not only did the ejido system represent a triumph for the many indigenous communities that fought alongside Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution to return feudal lands to communal use, it also reenacted a pre-Hispanic tradition that was all but eliminated during colonization. Indigenous interpreter Gaspar Antonio Chi reminded us of this struggle already in 1582:

In this way, the reform of 1992 reverted the victory achieved by indigenous communities during the revolutionary victory. It marked a relapse into colonial times where lands ceased to be shared with indigenous people and began to be dictated by early, predatory proto-capitalist forces. Indirectly, the reform of 1992 also allowed the purchase of agrarian lands, previously inalienable, by private and foreign capital. Garrett’s 1989 article already suggested the need for land reform to manifest his vision, stating that “land reform that puts idle land to work would make a big difference. Buying or leasing some lands as preserves will be required.”25 It is in this context, and after the ratification of NAFTA in 1994, that the relation between the IADB and “Mundo Maya” grew stronger. By 2003, the bank not only negotiated an investment plan of $150 million for the transnational Mayan region, but it also formalized the role of private investors and international institutions in this plan, which included the National Geographic Society.26 Against this complex network of interests, the monorail of John Berkey appears closer to science fiction. More than naturalizing the infrastructure, it is the ease of passage through the scenery that belies the financial mechanisms that underpin it.

AMLO’s Tren Maya is one of many proposals that has imagined a train as the driver of development in the southeast. Former Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto also had a similar fantasy. In 2012, he announced “Tren Transpeninsular,” a train connecting a smaller section of the Mayan Peninsula from Merida to Punta Venado. By 2015, Peña Nieto’s project was canceled for lack of funds. In 2017, the train came back when a group of local entrepreneurs expressed interest in investing in a shorter rail stretch from Cancun to Tulum.27 And, finally, as part of his presidential campaign promises, AMLO has picked this idea back up again. His original proposal was smaller in scale, stretching only nine hundred kilometers.28 Tren Maya is now expected to consist of fifteen stations across 1,500 kilometers—and far from the minimal monorail imagined by John Berkey, it will pass through 1,828 localities and 163 ejidos.29 Despite the government’s claim that the train will not adversely affect these communities, it is hard to imagine a scenario in which many of these localities, ejidos, and larger territorial relations are not radically altered by the train. This mega-development cocktail—mixing foreign investment, private capital, and the encroachment of racist practices—is exactly what the Zapatistas fear so much: a continuation of the destruction they have already experienced for generations.

The Promised Job

As part of this machine of development, the train hinges on the promise of job creation and the further integration of indigenous peoples into a wider economic program of national development. Alongside Tren Maya, other mega projects have been proposed to diversify the economy in the area. Among those is another rail line, the Tren del Istmo, that aims to improve the connection from the port of Salina Cruz in the Pacific Ocean to the port of Coatzacoalcos in the Gulf of Mexico—creating an alternative distribution network to that provided by the Panama Canal. This “inter-oceanic” route was schemed up by Charles V five centuries ago.30 While the route remains the same, the narrative today has changed. For the emperor the purpose of the inter-oceanic route was openly extractivist and made no gestures of benefiting the indigenous people. The current federal administration, on the other hand, has argued that this larger network of rail infrastructure is for the people of Mexico’s southeast. AMLO insists that these mega-infrastructural projects will bring jobs and assistance to the region. The Zapatistas, however, rightly see AMLO’s projects as the perpetuation of (neo)colonial politics, which (alongside this “assistance”) inevitably bring an interest in the fertile, uranium- and silver-rich ground of the southeast for massive commercial agricultural expansion.31

The Zapatistas’ concern is just as much economic—related to the predatory practices of extraction that accompany this type of developmentalist strategy and that threaten common lands and environmental diversity—as it is affective. This affective politics is most poignantly voiced by indigenous women in the region who have long struggled against the patriarchy and the coloniality of Western labor practices.32 Ever since the group’s formation, female Zapatistas have been advocating for their inclusion in processes of self-governance, for their participation in guiding collective forms of living, and for gender equality. Their message is clearly captured by Insurgente Erika, a representative of Zapatista women, who, during the opening of the First International Gathering of Women Who Struggle, stated, “It is not the work of men or of the capitalist system to grant us freedom. On the contrary, it is the work of the patriarchal system to maintain us in submission.”33 This position against Western developmental labor practices has become even more important today in the context of AMLO’s megaprojects. Speaking about Tren Maya, an anonymous group of feminist Zapatistas added the promoters of the project “want us to become their peons, their servants, to sell our dignity for a few coins a month… They think that what we want is a wage. They cannot understand that what we want is freedom… They don’t understand that what they call ‘progress’ is a lie, that they cannot even take care of the safety of women, who continue to be beaten, raped and murdered in their progressive or reactionary worlds.”34 For the Zapatistas, AMLO’s proposed plan for the region is a tool of (gendered) disempowerment that perpetuates the colonial practice of extracting surplus from the most vulnerable while suspending their capacity to decide a means of emancipation.

The promise of jobs is only a symptom of a wider obliteration of indigenous lives and livelihoods. The metrics that guide this type of development scheme, and the forms of benefits and assistance that underlie it, remain incapable and distant from the various modes of existence cultivated by indigenous communities. To borrow Kathryn Yusoff’s argument, it is an attempt to render racially differentiated subjects “inhuman,” operationalizing their differences to cultivate normalcy while denying the possibility of practicing alternative forms of life—a life outside the extractive capacities of capitalism.35 Far from a simple, cross-cultural misunderstanding, it is a new technique that reinforces a centuries-old practice of repression. The error this development makes is not representational, as was the case in Battista Agnese’s map. Rather, it is a willful rejection of the knowledge and practices of indigenous people—undermining their political right for self-determination while mapping both their material and affective resources.

How can a development of this sort account for the multiple realities and expressions of freedom in this region? For the community of El Bosque in Chiapas, freedom translates to kolem in Tsootsil, which also involves health.36 In Mayan Ch’ol, freedom translates as wejel, which also means “to fly.”37 Economic freedom will never understand this. The development framework of Tren Maya cannot understand that the only reason for which the many indigenous peoples of the area could willingly integrate into a wider ideological network is only as a means of resistance to a common struggle. The Zapatistas intentionally use anonymity to consolidate the political resistance of various indigenous groups. Behind their masks, differences remain. Their attempt to become one is only a means of political mobilization, an instance of political creativity. They are, perhaps, a living example of the relation that Judith Butler sees between two apparently opposite concepts: vulnerability and resistance. For Butler, to understand vulnerability only as a deficiency that must be protected paternalistically by an external group is to deny the possibility of a group to act politically.38 This is exactly the posture that this form of infrastructure-driven development embraces, the neutralization of resistance by making invisible political struggle. This is the violence of Tren Maya.

Despite its stated intention to address the vulnerabilities and multiple identities of indigenous peoples in the southeast, Tren Maya is nothing but a means to interpolate them into the logics of advanced capitalism and state control. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is growing resistance to the project, and it is even less surprising that the groups resisting Tren Maya, such as the Zapatistas, are constantly defamed in popular media. In response to this, more than seven hundred intellectuals, activists, and cultural producers from around the world, including luminaries like feminist Silvia Federici and artist Carlos Amorales, have recently co-signed a letter calling for the legitimization of the Zapatista struggle.39 For them, the inability of the Mexican State to address the political demands of indigenous communities is not a matter of disinformation or gaps of knowledge of indigenous practices. It is instead an act of political violence that denies a space within the state to enable the possibility for alternative forms of life.

As such, Tren Maya represents a Potemkin infrastructure. Behind its technologically redemptive ambitions and its gestures toward indigenous representation, all put onstage for the world to behold, the train undermines and covers the political voice of the indigenous peoples and their struggles to carve out and hold a space within and separate from the State. And, yet, it is important to remember that the diagnosis of their vulnerability is not only part of a developmental machine of the present that perpetuates paternalistic State politics; it is also a historical construct. As Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano famously suggested, “our [Latin American] wealth has always generated our poverty by nourishing the prosperity of others.”40

-

Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s speech in Candelaria, Campeche, February 23, 2019, link. ↩

-

A. M. Babu, “Postscript,” in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rodney (New York: Verso, 2018), 349. ↩

-

Claudia Ramos, “En riesgo, la mitad de la población nacional de jaguars si el Tren Maya no cumple ley ambiental,” Animal Politico, December 14, 2018, link. ↩

-

The official ceremony to kick off Tren Maya took place on December 16, 2018, in Palenque Chiapas. It was advertised as “Ritual of the Original Peoples to Mother Earth for the Mayan Train.” ↩

-

For feasibility studies see, Claudia Ramos, “Qué requisites require una obra de infrastructura (el Tren Maya aún no cumple ninguno),” Animal Politico, November 14, 2018, link. For budget see, Redacción Animal Político, “Tren Maya costaría hasta 10 veces más y traería riesgos ambientales si no se planea bien: IMCO,” Animal Politico, March 19, 2019, link. For the role of private contractors see, Redacción Animal Político, “Gobierno de AMLO adjudica sin licitar el 74 percent de los contratos,” Animal Politico, March 28, 2019, link. ↩

-

For AMLO’s presentation of Tren Maya see, Misael Zavala, “Estímulos, a quien invierta en Tren Maya, dice AMLO,” El Universal, December 17, 2018, link. For Subcomandante Moisés’s speech see, “El EZLN advierte que se opondrá al Tren Maya y a la Guardia Nacional,” Animal Politico, January 1, 2019, link. ↩

-

For background on Emiliano Zapata, see Jesús Sotelo Inclán, Raíz y razón de Zapata (Anenecuilco, MX: Editorial Etnos, 1943). For Zapata’s role in the Mexican Revolution, see Gildardo Magaña, Emiliano Zapata y el agrarismo en México (Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de la Revolución Mexicana, 1985).

We are a product of five hundred years of struggle: first, led by insurgents against slavery during the War of Independence with Spain; then to avoid being absorbed by North American imperialism; then to proclaim our constitution and expel the French empire from our soil; later when the people rebelled against Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship, which denied us the just application of the [agrarian] reform laws, and leaders like Villa and Zapata emerged, poor men just like us who have been denied the most elemental preparation so they can use us as cannon fodder and pillage the wealth of our country. They don’t care that we have nothing, absolutely nothing, not even a roof over our heads, no land, no work, no health care, no food or education, not the right to freely and democratically elect our political representatives, nor independence from foreigners. There is no peace or justice for ourselves and our children.[^8]

-

Redacción Animal Político, “Organizaciones acusan simulación en consulta de Tren Maya; piden respeto a pueblos originarios,” Animal Politico, April 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Jorge Monroy, “Tren Maya podría incrementar a 4 millones los turistas internacionales: Miguel Torruco,” El Economista, November 20, 2018, link. ↩

-

Refer to Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, Hannah Appel, eds., The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 1–41. ↩

-

Tania Murray Li, The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 123–155. ↩

-

Murray Li, The Will to Improve, 7. ↩

-

United Nations, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 32–2 (March 2008), 12, link. Also see International Labor Organization, C169: Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (June 1989), link. ↩

-

Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 71. Drawing on Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1997), 24. ↩

-

Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, 71. ↩

-

Jennifer Bair, “Constructing Scarcity, Creating Value: Marketing the Mundo Maya,” in The Cultural Wealth of Nations, eds. Nina Bandelj and Frederick Wherry (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 177–196. ↩

-

Wilbur E. Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” National Geographic, vol. 176, no. 4 (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1989), 436. ↩

-

I would like to thank Aaron Hauptmann for his assistance in gathering material for this piece. ↩

-

Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” 435, 438. ↩

-

Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” 435. ↩

-

Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” 422. ↩

-

Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” 422. ↩

-

Susan Goldberg, “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It,” in “The Race Issue,” National Geographic, April 2018, link. ↩

-

Naomi Adelson, “El Mundo Maya sin Mayas,” La Jornada, December 24, 2000, link.

In olden times all lands were communal and there were no property marks, except between provinces, for which reason hunger was rare as they planted in different places, so that if the weather was bad in one place, it was good in another. Since the Spaniards have arrived in this country, this good costume is being lost, as well as the other good customs which the natives had, because in this land there are more vices to-day than fifty years ago.[^26]

-

Garrett, “La Ruta Maya,” 422. ↩

-

Bair, “Constructing Scarcity, Creating Value: Marketing the Mundo Maya,” 177–196. ↩

-

“Buscan reimpulsar propuesta de tren entre Cancún y la Riviera Maya,” Diario de Yucatán, May 22, 2017, link. ↩

-

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Proyecto de Nación 2018–2024 (Mexico City: Morena, November 2017), 208, 213–215. Also see, “‘Construiremos un tren Cancún-Tulúm-Calakmul-Palenque’: AMLO,” Regeneración, December 30, 2017, link. ↩

-

Ariadna Ortega, “Comunidades en la ruta del Tren Maya,” Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible, link. ↩

-

Max L. Moorhead, “Hernán Cortés and the Tehuantepec Passage,” the Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 29, no. 3 (1949): 370–379. ↩

-

Mariana Mora and Pablo González, “El Zapatismo y la disputa por la historia (presente),” La Jornada, Febrauary 2, 2019, link. Also see the press release announcing the cancelation of the Second International Gathering of Women Who Struggle: “No habrá encuentro de mujeres en territorio zapatista,” LatFem, February 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Hilary Klein, Compañeras: Zapatista Women’s Stories (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2015). ↩

-

Speech by Insurgente Erika given at the First International Gathering of Women Who Struggle, Caracol of Morelia, Chiapas, March 21, 2018, link. ↩

-

No habrá encuentro de mujeres en territorio zapatista,” LatFem, February 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. ↩

-

Al-Dabi Olvera, “Libertad se habla en tsotsil,” El Color de la Pobreza, February 10, 2019, link. ↩

-

Judith Butler, “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance,” in Vulnerability in Resistance, eds. Judith Butler and Sabsay Gambetti (Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2016), 12–27. ↩

-

“Carta de Solidaridad y Apoyo a la Resistencia y la Autonomía Zapatista,” DesInformémonos, January 16, 2019, link. ↩

-

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997), 2. ↩

Ivonne Santoyo-Orozco is assistant professor of architecture at Iowa State University. Her current work investigates relationships between architecture, private property, and governance in Mexico.