It is worth remembering that there was no Occupy Ground Zero. During the fall of 2011, a collective attempt was made to reclaim Lower Manhattan, if not for the indigenous Lenape who gave the island its name then for the “99 percent” on whose backs “Wall Street” had built, and continues to build, obscene material wealth. Yet, even as Occupy Wall Street resettled Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park, “Wall Street” was relocating, at considerable public expense. Not least, $115 million of direct subsidy and $1.65 billion in tax-free bonds had helped entice Goldman Sachs to build its new headquarters at 200 West Street, on the other side of Ground Zero, just northwest of the ominously named Freedom Tower (now One World Trade Center).1 Between the old symbolic center of financial capitalism and its new extension sat “sacred ground”—what was then a vast construction site and what is now a publicly subsidized real estate development with an evangelical, neo-Gothic cathedral of shopping (“The Oculus”) looming over the sunken, water-washed memorial at its center.

The political theorist Wendy Brown has explained how border walls, like the walls of religious buildings, symbolically sanctify the ground they seem only to protect. As economic globalization has washed over national borders, Brown argues, many nation-states have responded by fortifying their territory in an exaggerated attempt to recapture and reassert sovereignty.2 Lower Manhattan’s post-9/11 “sacred ground” is one archetype of this political theology of nationalism—sanctification through security. But in other ways, Ground Zero and its surroundings may also represent a limit case, particularly when it comes to the seawalls that are increasingly part of Lower Manhattan’s future. Belonging to a terrestrial politics of space, seawalls, too, sanctify territory. More than other border walls, however, they also disclose contradictions swirling through the carbonized, warming air on which epochal change is borne.

A year after Occupy, in October 2012, the storm surge from Hurricane Sandy flooded the Ground Zero construction site. The storm left forty-three dead across all five New York City boroughs and close to two million without electricity for days and, in some cases, weeks. Though the new Goldman Sachs headquarters was in the flood zone, its lights stayed on thanks to a backup generator. Despite this beacon of post-9/11 rebuilding made nautical, by this time the dream of a renewed financial district around Ground Zero was already fading. Beginning with Condé Nast in the former Freedom Tower, big media was the new message. Ground Zero developer Larry Silverstein had been seeking an anchor tenant for Two World Trade Center, the last of the site’s four commercial office towers, then being designed by Norman Foster and Partners. Citigroup, a top prospect, demurred, and 21st Century Fox, the parent company of Fox News, entered the fray. With Fox came Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), headed by the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels. According to Wired magazine, Fox patriarch Rupert Murdoch’s son James, a company executive, had been taken by BIG’s design (with imagineer Thomas Heatherwick) for the expansion of Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. If Silverstein wanted Fox as an anchor tenant, he would have to exchange Foster’s architecture for BIG’s.3 Silverstein complied, and, beginning in 2014, Ingels and his team designed a glib, eighty-story House of Fox, even going so far as to exhibit a Fox News antenna atop the building in the project’s marketing video.4

According to a recent exposé by the New York Times, James Murdoch “reads as an archetype of today’s global power elite,” a former “family rebel” who sought to make all of Fox’s offices carbon-neutral while his Machiavellian brother Lachlan (who now runs the company) embraced ultra-nationalism and “believes that the debate over global warming is getting too much attention.”5 That Ingels’s patron, James-the-reformer, was the loser in an intra-family power struggle transparently parodied (or foreshadowed) by the HBO television series Succession does not excuse the architect’s craven service to Fox News, nor does the project’s pre-2016 start date. Like other architectural starlets, Ingels aggressively injects his persona into the art of every deal. So, that persona—let’s call it “Bjarke,” as the students do—must be given due credit for the results. That means the name “Bjarke” is now permanently, historically attached to the name “Murdoch,” whatever else may follow.

As it happens, much has followed in Lower Manhattan. Fox eventually abandoned the Ground Zero tower, Silverstein offered prospective anchor tenants the choice of Foster’s design or BIG’s, and the developer now threatens to build the Fox-less BIG design on spec.6 In 2014, the Obama Administration’s Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force launched a design competition under the auspices of a newly formed nonprofit, Rebuild by Design, soliciting proposals for some of the region’s hardest-hit sites. Of the seven winners, the scheme for Lower Manhattan designed by BIG has received the most attention. “Bjarke’s” collaborators on the proposal were: One Architecture, Starr Whitehouse, James Lima Planning + Development, Green Shield Ecology, AEA Consulting, Level Agency for Infrastructure, ARCADIS, and Buro Happold. None of them, however, were fortunate enough to have their firm included in the project’s nickname: “The Big U.”7

It may be said of reality television stars that they lack a superego. For so pure a product of the culture industry as “Bjarke” (a.k.a. “BIG,” a.k.a. “big.dk”—look it up), the vocabulary of psychoanalysis must be extended to a nonhuman commercial persona. As in the Fox tower but more so, the untroubled persona of this individual-collective author of the Big U is tinted green. The proposal consists of about ten miles of landscaped flood protection wrapping the Lower Manhattan coastline, in the form of berms and gentle gradients to absorb the water’s inexorable rise, plantings, deployable structures, furniture, and a “reverse” aquarium in Battery Park. As soft infrastructure, the ensemble is conceived under the sign of “resilience,” a deceptive term that replaces what 1970s environmentalist discourse called “survival”—which for all its Darwinian overtones at least named the life-and-death stakes even before climate change was widely understood. Therapeutically soothing, “resilience” reeks of an entrepreneurial moralism that preaches tenacity, grit, cleverness, and against-all-odds perseverance. None of this is “Bjarke’s” doing; it is merely the discursive and historical context in which the Big U was conceived and must be assessed.

An undated report authored by the “BIG Team” provides the most detailed public description of the proposal, post-competition.8 The report’s tone is foreboding; the design’s is electric and accessible. The obligatory, pert equation of “this + this = innovation” reconciles a false antinomy—Jane Jacobs versus Robert Moses—by combining large-scale infrastructural planning with “community” design. Despite their acrimonious battles, Jacobs and Moses do not stand for opposing ideologies but rather represent two sides of the neoliberal coin: greenmarket “community” and the not-so-invisible hand of the state. The “people”-centered discourse of the Big U, and of Rebuild by Design in general, demonstrates the compatibility of large-scale, master-planned urban restructuring with a self-congratulatory narcissism scaled to the individual. The BIG Team report concludes with letters of support addressed to Barack Obama’s Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary Shaun Donovan, followed by a gratuitous “thank you” to a long list of “community members.” At no point, however, and despite the direct appeal to government, are these individuals addressed or presented as rights-bearing citizens of a polis. Rather, the report and the project interpellate them as caretakers of an oikos, a household (the ancient Greek root of both “economy” and “ecology”) in need only of management and maintenance. This is the discursive work that state-sponsored, tax-abated, public-private design for “community” does: it replaces the dissenting citizen with the compliant consumer. Who, after all, can argue with a “community member”?

That full membership in this “community” is purchased rather than socially and politically forged is disclosed by the project’s most telling slip. As the Rebuild by Design website puts it, with reference to the project’s discrete, neighborhood-based “compartments”:

Like the hull of a ship, each can provide a flood-protection zone, providing separate opportunities for integrated social and community planning processes for each. Each compartment comprises a physically separate flood-protection zone, isolated from flooding in the other zones, but each equally a field for integrated social and community planning. The compartments work in concert to protect and enhance the city, but each compartment’s proposal is designed to stand on its own.9

In other words, the Big U is a Robert Moses–scaled cruise ship that, at the level of the neighborhood “compartments,” breaks down into a flotilla of smaller, Jane Jacobs–scaled dinghies. Like the “hull of a ship,” each compartment divides its members from their neighbors but also and most importantly, from the majority of the Earth’s imperiled inhabitants who have no access to such infrastructure in the first place.

There is no denying the need to design and build such lifeboats. But there is also no denying that they are by definition instruments of exclusion. This is borne out by criticism of the Big U project since its inception, as well as by recent interventions like Billy Fleming’s “Design and the Green New Deal” that challenge resilience dogma more generally.10 Was Wall Street to be gifted a yacht while Brooklyn’s Red Hook, the Rockaways in Queens, or Staten Island’s east and south shores were left to fend for themselves? The fact that the city has spent considerable sums in remediating these and other low-lying coastal neighborhoods devastated by Sandy has done little to dispel the message sent by the Big U that some neighborhoods matter more than others. While, within the U itself, residents of public housing and other cabin-class passengers whose needs risked being overlooked were welcomed into a years-long consultation in which what mattered most had already been decided: That the design and construction of lifeboats was not a political question, only a managerial one. Lifeboat design sorts populations into classes and proceeds to accommodate all within the preset limits of their status. Words like “solidarity” and “collective” are excluded from the lexicon. Public funding is welcomed, but public governance and public—i.e., democratic—accountability are at best tolerated as temporary inconveniences along the road to the public-private partnership.

The social and economic inequality against which the occupation of Zuccotti Park—a “Privately Owned Public Space” (POPS)—was directed in 2011 is not an unfortunate by-product of financial capitalism; it is the plan. The same goes, though more subtly, for anti-democracy. Occupy Wall Street reclaimed the political voices of non-elite citizens and noncitizens by placing bodies in the streets, to contest the very premises of a system that does everything to silence those voices by brute economic and political force. Social movements like the Movement for Black Lives and the Standing Rock coalition have focused attention on the gendered, racial violence that is structural to this system, which has been reinforced by official support for white patriarchy and white supremacy. The antidemocratic project is now also poised to exploit the normalization of climate emergency.

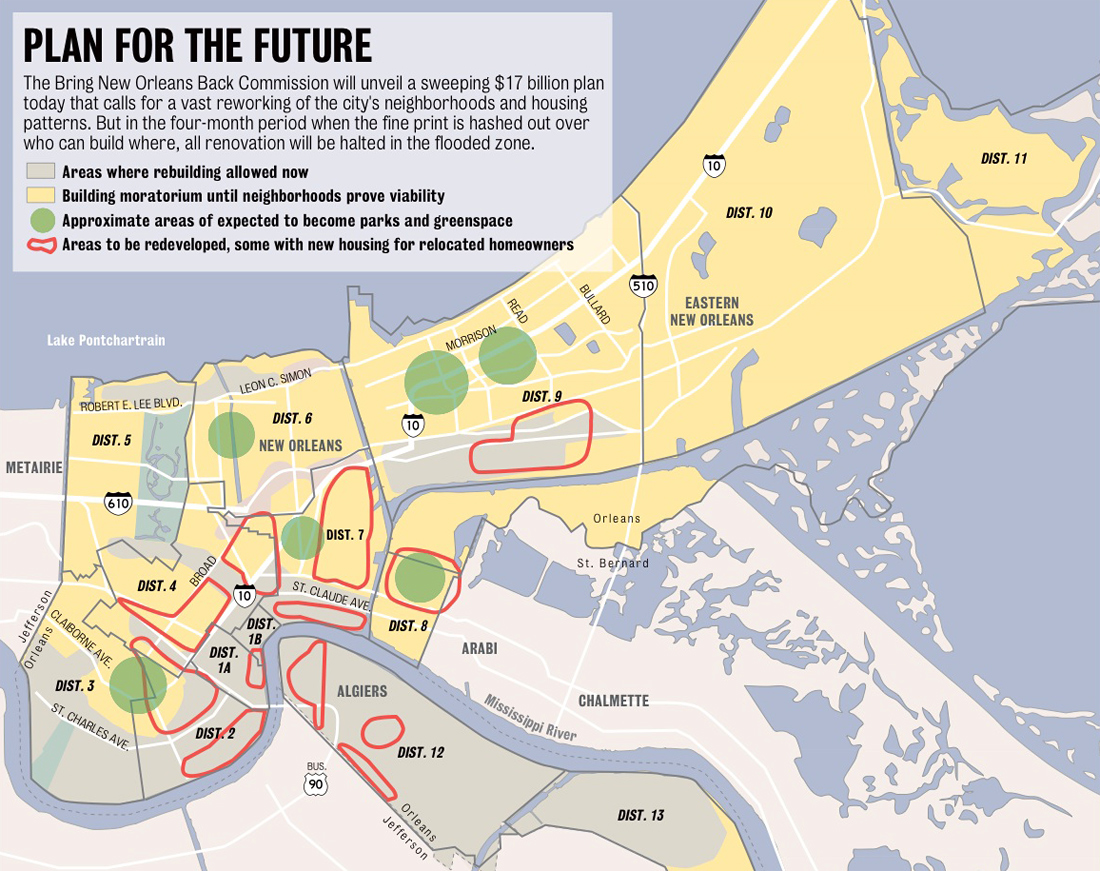

One important testing ground for the curtailment of democracy through infrastructural redevelopment and privatization in the era of climate change has been New Orleans. Even before almost two thousand died and many thousands more—a vast majority black—left the city during and after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, efforts were underway to privatize the city’s public schools and public housing. Katrina accelerated that process. Among its consequences was the notorious “green dot map” proposed by New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin and based on recommendations by the Urban Land Institute (an influential real estate lobbying group), which designated six neighborhoods flooded and evacuated during the hurricane as future parkland.11 Most were among the city’s poorest districts and were majority black. A furious public reaction prevented the plan’s execution, but the city’s remaining public housing, most of which survived the storm, was condemned, demolished, and largely replaced by publicly subsidized, private, mixed-income development. Every teacher in the public school system was fired, and that system was replaced by a citywide network of charter schools.12

During this same period, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg began incrementally privatizing public housing with his proposal, tested on several sites, to sell or lease land surrounding existing housing complexes to developers of mixed-income “affordable” (i.e., for-profit) housing. His successor, Bill De Blasio, shelved the plan, which also faced opposition from New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) residents who saw the writing on the walls: first sell the land, then sell the buildings, then evict the tenants. The strategy has since been revived in the face of threats by current HUD secretary Ben Carson to bring the entire system under an austerity regime.13 Though Hurricane Sandy also flooded the public housing complexes that stretch up Lower Manhattan’s eastern flank around the Williamsburg Bridge, no evictions or demolitions followed. Still, the low-lying, flood-prone ground underneath and adjacent to this housing remains a key front on which the antidemocratic project is likely to advance.

How? The Big U is especially rhetorical about its pragmatism. From the promotional video to the public report, the tone is one of commonsense necessity and playful engineering. Self-sufficiency is the overarching message, delivered in emoji-like, off-the-shelf icons of “community” and urban recreation. Behind it all, however, runs the apocalyptic loop of post-Katrina abandonment, desperation, and death, which was replayed with particular ferocity during Sandy in what New Yorkers refer to as the “outer boroughs.” In other words, as a lifeboat, the Big U is also—symbolically—a soft, resilient border wall that extends the sacred ground of “Wall Street”/Ground Zero to the island’s lower edge. The ongoing remediation of coastal areas in New York’s outer boroughs does little to neutralize the sinister, structural threat: lifeboats for some but never for all.

The principle of exclusion through privatization is quietly refined in the unassuming pages of a follow-up proposal for governing the remediated parkland on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The design of the Big U having been selected, Rebuild by Design turned its attention to long-term stewardship, joining with the neighborhood organization Good Old Lower East Side (GOLES) to issue a call for proposals for a piece of the U that offered alternatives to the widespread “conservancy” model. The winner was a member of the “BIG Team,” James Lima Planning + Development, partnering with the nonprofit Trust for Public Land. Introducing Lima’s proposal, Rebuild’s managing director Amy Chester noted that the conservancy model, wherein a nonprofit (i.e., private) entity contracts with the city to manage otherwise public parkland, had been developed “to address shortages in funding and opportunities for enhancements.”14 In other words, when it is politically infeasible for a democratically accountable city agency to maintain public lands, a public-private partnership transfers responsibility to a nongovernmental actor. This model has long been controversial, especially among disenfranchised groups. Rebuild wanted a “community-oriented” alternative that would “address equity” in funding mechanisms for maintenance and operations while avoiding or at least mitigating “externalities” like gentrification. Honorable as these aims are, the official remit remains silent about enhancing democracy, offering only enhanced “dialogue” in its place.

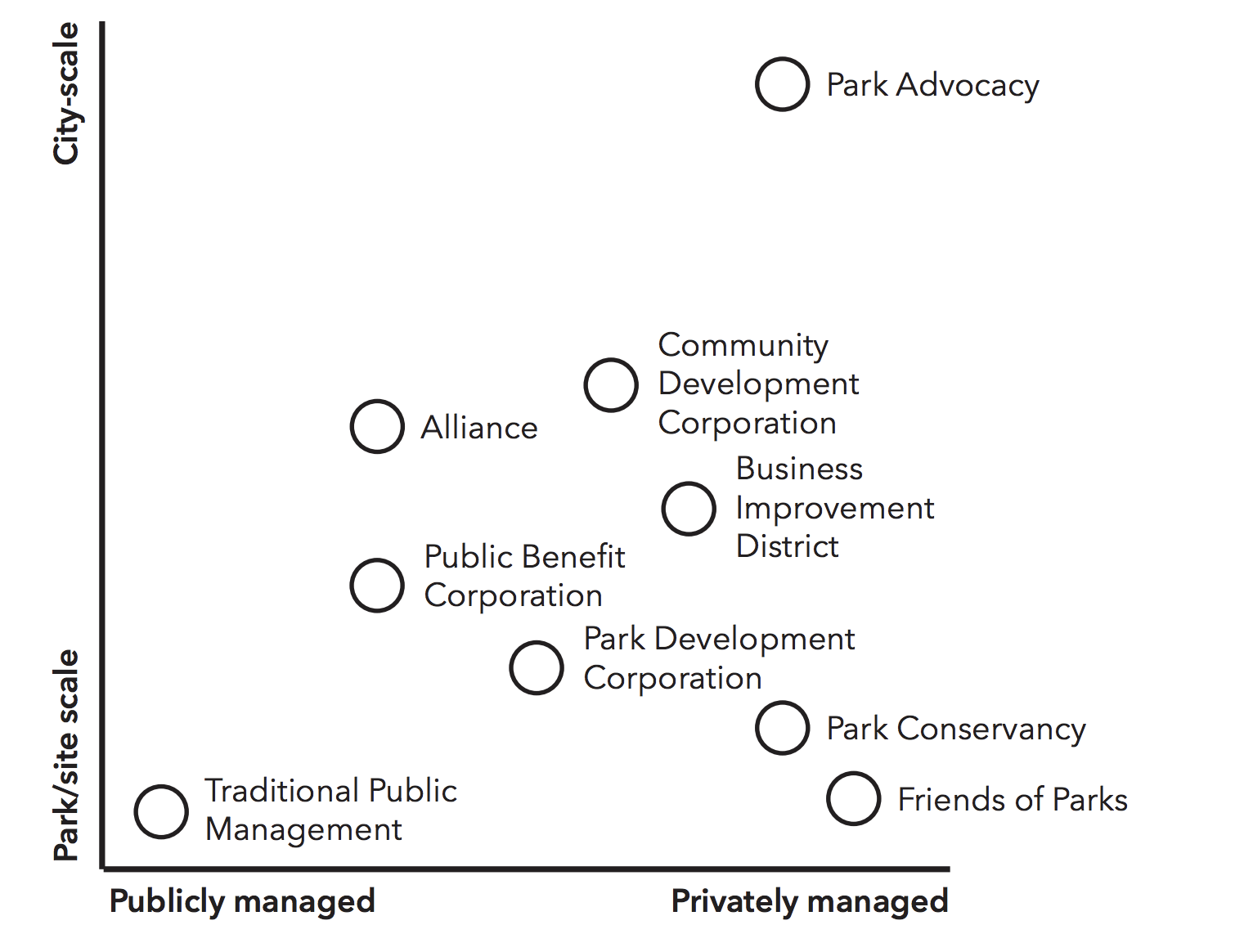

The Lima–Trust proposal, published in December 2018, is titled “Building Bridges: A Community-Based Stewardship Study for an Equitable East River Park.”15 It centers on existing parkland that would be made resilient and absorbed into the Big U on either side of the Williamsburg Bridge, immediately adjacent to four large NYCHA public housing complexes. Speaking a consumer’s language of “assets” and “amenities,” “Building Bridges” makes its case by surveying the context and studiously examining available models of governance. These are usefully plotted on a graph that runs from public to private along the X-axis, and park to city scale along the Y-axis. “Traditional Public Management” occupies the far-left position, while “Park Conservancy” and “Friends of Parks” run neck-and-neck on the far right, with the “Alliance” model (already announced as the winner in the table of contents) solidly center-left. As the narrative moves to a more detailed chart of “key” stewardship models, the “traditional” public model drops out, only to reappear again in a national sample of thirteen precedents selected for their concern for equity or disadvantage. From these “key” models, another “spectrum” compares three examples of “community-driven park & resilience stewardship”: The Gentilly Resilience District in New Orleans (“City management with strong community engagement”); Washington, D.C.’s “Building Bridges across the River” (“City & community delegated roles”); and New York’s Bronx River Alliance (“City & community co-management”), which will turn out to be the prototype. Unexplained is the counterintuitive distinction between “city” (i.e., local government) and “community” (i.e., nonprofit, private actors) in all three cases. Translated, however, into the terms of the BIG proposal of which Lima was a co-author, the New Orleans case appears to be mostly Robert Moses with a bit of Jane Jacobs, while the Bronx River Alliance is more Jacobs, less Moses. In all cases, rhetorical virtue lies with an unelected “community,” inefficiency and arbitrary authority with a democratically accountable state.

Anyone who has ever interacted with any of the countless agencies that comprise the City of New York might be inclined to agree. But the ultimately antidemocratic message of this appeal to “community” design and stewardship is secured when the report’s syntax of lists, charts, and bullet points restricts further comparisons to “Typical agreements in public-private stewardship of parks,” followed by an inventory of “Key aspects of successful models,” all of which exclude without explanation the “traditional” model of fully public custody, funding, and maintenance. In place of an intersectional definition of “success” are three criteria: equity, fundraising, and capacity. Readers looking for a “full set of case studies” are referred to Appendix B, which merely adds the Great Rivers Greenway in St. Louis to the three others. Of the four, Gentilly’s Mirabeau Water Garden is the only model denominated “public, with community engagement,” wherein the “city leads and manages.” The literal-minded reader is left to conclude that this characteristic, and none other, accounts for its falling off the chart of “success” and its being rejected by Rebuild by Design as a model for New York. The report’s intended audience, however, knows well that “traditional” public management, reclaimed for greater equity and more democracy, not less, was never on the table in the first place.

Gentilly was among those neighborhoods marked with a green dot—potential parkland—on the controversial map of post-Katrina New Orleans. Its public library has since been rebuilt, but the neighborhood’s mostly black population, nearly returned to pre-Katrina levels, is now served like the rest of the city only by charter schools. Along with Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Gentilly, which abuts Lake Pontchartrain’s levees, is also slated to receive federal funds through HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition. The neighborhood’s Mirabeau Water Garden is a public works project on land donated to the city by a convent severely damaged by Katrina and later destroyed by fire, to avoid it falling into the hands of real estate developers. The plan calls for soil stabilization, a large storm water detention pond, and wetlands filtration, all overseen and managed by the City of New Orleans.16 If such a straightforward form of public sovereignty is still plausible even in the Big Easy, a city beset by privatization left and right, why is it so unthinkable in the Big Apple?

Burdened by contradictions of its own, this “traditional” model is not, of course, an end in itself. As Occupy Wall Street demonstrated, there are more equitable and more democratic alternatives to formal, representative democracy and a highly centralized public sector. But in a political-economic environment where voting rights are transparently curtailed, national borders fetishized, inequality deliberately exacerbated, and eco-apartheid gradually normalized, formal democracy and not its opposite should be a minimal baseline of “success.” A public sphere in which triumphalist neoliberal proposals like the Big U are greeted as progressive is therefore hardly public. Likewise, understandable as they are as attempts to make the best of an embarrassing situation, efforts like Lima’s to salvage an “alliance” of civic actors out of the debris of citizenship cannot substitute for a properly political response.

Enter the City of New York’s Department of Design and Construction. In September 2018, as Lima’s group began their work, their ultimate client, the City’s East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, unveiled an alternative design for the Lower East Side Park. Gone were the berms, benches, and “community” spaces of the Big U. In their place was a run-of-the-mill waterfront park, elevated on ten feet of landfill above the existing ground level. A solid, vertical seawall replaced the gentle slope rising toward the BIG berm, defiantly defending the park against the 16.5-foot storm surge predicted with a thirty-inch sea level rise. Replacing soft infrastructure with hard, the city’s designers argue that the new proposal, which has been making the rounds of the community boards, NYCHA residents associations, and neighborhood organizations, will be faster to realize while avoiding construction inconveniences necessitated by the BIG scheme.17 No mention is made of governance or stewardship in the presentation and design materials available online.18 Rebuild by Design’s public-private “alliance”—more New Orleans than New Orleans itself—sits waiting in the wings.

Architects and urban planners schooled in the language of the 1960s dissident left are accustomed to speaking of a “politics of space.” What does such a politics look like in the era of climate change, when “space” is recoded as carbonized air? Unlike residents of the Louisiana bayous and other coastal areas, where many of the most vulnerable front-line communities are, Lower Manhattan’s residents have not (yet?) been confronted with the realism of managed retreat. Nor is there much serious talk of decarbonization amid the resilience-speak that guides the design of lifeboats soft and hard. Technically, these can seem separate issues, and the City of New York has recently passed significant legislation requiring building retrofits to improve energy performance.19 But, to rephrase a question posed by Billy Fleming, if you had a billion dollars to spend, what would you spend it on, a lifeboat or a windmill?

To complicate matters further, the two frequently combine. When complete, the parkland around Lower Manhattan will be basically carbon neutral, even as it secures the carbon empire’s metropole. So if not quite a zero-sum game, a politics of space that—again at a bare, reductive minimum—pits private sovereignty against public sovereignty now unfolds within a political economy of air that asks, lifeboats for some or decarbonization for all? This question, with its innumerable both/and variants, defines the new politics of design. With whom would you cast your vote: “Bjarke” or the New York City Department of Design and Construction? If the choice is unsatisfying, then perhaps it’s time to rewind the clock a few years, to that oil-and-blood soaked, zero-hour sanctification of Lower Manhattan’s ground that still echoes around the world, and ask, What have we done?

-

N. R. Kleinfield, “It’s a Goldman World,” the New York Times, June 29, 2012, link. ↩

-

Wendy Brown, Walled Spaces, Waning Sovereignty (New York: Zone Books, 2010). ↩

-

Andrew Rice, “Revealed: The Inside Story of the Last WTC Tower’s Design,” Wired, June 19, 2015, link. ↩

-

Jenna McKnight, “BIG Unveils Replacement for Foster’s Two World Trade Center Design,” Dezeen, June 9, 2015, link. ↩

-

Jonathan Mahler and Jim Rutenberg, “Planet Fox: How Rupert Murdoch’s Empire of Influence Remade the World; Part 1, Imperial Reach,” the New York Times, April 3, 2019, link. ↩

-

Nikolai Fedak, “Larry Silverstein Tells YIMBY Foster’s Design for 200 Greenwich Still a Contender, More,” New York YIMBY, September 11, 2018, link; Lily Katz, “Silverstein May Start Building Final WTC Tower without Signed Tenant,” Bloomberg News, February 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Details on “The Big U” are available on the Rebuild by Design website. ↩

-

Rebuild by Design, “The Big ‘U.’” Undated report. All rights reserved: BIG Team, link. ↩

-

Billy Fleming, “Design and the Green New Deal,” Places Journal, April 2019, link. ↩

-

Times-Picayune Staff, “Plan Shrinks City Footprint,” Times-Picayune, December 14, 2005, link. For a detailed critical survey of planning in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, see Carol McMichael Reese, Michael Sorkin, and Anthony Fontenot, eds., New Orleans under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning (New York: Verso, 2014). ↩

-

On housing, see Richard A. Webster, “New Orleans Public Housing Remade after Katrina. Is It Working?” Times Picayune, August 20, 2015, link. On schools, see “All New Orleans Public School Teachers Fired, Millions in Federal Aid Channeled to Private Charter Schools,” Democracy Now!, June 20, 2006, link. ↩

-

Kriston Capps, “Ben Carson Asserts New Control over New York’s Housing Plans,” Citylab, January 31, 2019, link. See also Luis Ferré-Sadurní, “To Save Public Housing, New York Warily Considers a New Approach: Tear Some Down,” the New York Times, April 25, 2019, link. ↩

-

Amy Chester, “Letter from the Director,” in James Lima Planning + Development and The Trust for Public Land, “Building Bridges: A Community-Based Stewardship Study for an Equitable East River Park,” a report prepared for Rebuild by Design, December 2018, link. ↩

-

James Lima Planning + Development and The Trust for Public Land, “Building Bridges: A Community-Based Stewardship Study for an Equitable East River Park,” a report prepared for Rebuild by Design, December 2018, link. ↩

-

Gentilly Resilience District, “Mirabeau Water Garden: Fact Sheet,” City of New Orleans, August 2018, link; and The Trust for Public Land, “How Nuns Joined the Fight against Climate Change,” May 15, 2018, blog post, link. ↩

-

Ameena Walker, “Manhattan’s East Side ‘Resilient Park’ Get Overhauled,” Curbed New York, September 28, 2018, link. ↩

-

New York City East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, “Meetings and Workshops,” available online at the project’s website, link. ↩

-

Caroline Spivack, “NYC Passes Its Own ‘Green New Deal’ in Landmark Vote,” Curbed New York, April 18, 2019, link. ↩

Reinhold Martin is a professor of architecture at Columbia GSAPP, where he directs the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture.