In his latest piece in the Atlantic, “The Anthropocene Is a Joke,” science journalist Peter Brannen argues that it’s arrogant to think that human impact on the planet could take the form of an epoch. “The idea of the Anthropocene inflates our own importance by promising eternal geological life to our creations. It is of a thread with our species’ peculiar, self-styled exceptionalism—from the animal kingdom, from nature, from the systems that govern it, and from time itself.” Our time on Earth will have been much, much, much too short for the anthropogenic environmental damage that we imagine having such long-term consequences to show up as anything more than “an odd, razor-thin stratum hiding halfway up some eroding, far-flung desert canyon.”1

The essay’s provocative title is misleading. It’s not really a critique of the Anthropocene idea, which, though it relies on the language of geological epochs, is actually a framework for thinking about the present. Instead, the essay is about geological time, which, Brannen writes, is “deep beyond all comprehension.” Furthermore, as much as he strives to restore humans to their correct—tiny, insignificant—place in natural systems, his particular framing of the situation functions according to its own internal logic of separation. By arguing that humans won’t have been around long enough to matter geologically, Brannen creates an unbridgeable gulf between the human and the geological and shows that the future of the planet belongs—as it always has—to rock.

But rock is never just rock. While Brannen is explicitly unconcerned about human extinction, his finely crafted descriptions of rock and fossil eons from now (reminiscent in their degree of detail of Alan Weisman’s 2007 book The World Without Us) have a distinctly apocalyptic tone. And apocalypse is reassuring, because it allows us to imagine release from the horrors of the present and a new beginning in their place. “In spite of this incredible effort” to have a lasting impact on Earth, he writes, “all is vanity.”2 His powerful evocations of a future in which there is almost no record of humans function to move Brannen’s readers out of today’s cultural climate of precarity, loss, and guilt around anthropogenic environmental degradation and its related extinctions. The future he crafts is a much safer one, marked by timelessness, silence, and depth.

To put it more strongly, given Brannen’s insistence on meaninglessness, it’s notable how much mountains function as bearers of meaning in his piece. His mountains are impervious and bare, but this is the source of their power, their depth. It’s perfectly in keeping with the classic mountain imaginary, the very same one that has animated mountaineering culture since Petrarch, the first recorded person to ascend a mountain just to see the view from the top, first stood on the summit of Mont Ventoux sometime in the mid-1300s. The practice of mountaineering has developed in ongoing relation to how mountain environments signified culturally, a long, complex, and fascinating set of processes that changed over time. By the end of the eighteenth century, mountains were at the center of colonial knowledge production (Humboldt) and the new discipline of aesthetics (Kant). The highest and hardest ascents didn’t take place until less than a hundred years ago and were considered great achievements precisely because of the severity and recalcitrance of the environments in which they happened, the Himalayas. The harder the mountain appeared in the public imagination, the greater the achievement.

Thus, while Brannen is obviously right that mountains themselves don’t care about human activity, this is hardly insignificant to those who climb them and the publics that watch. As his piece itself demonstrates, rock’s very recalcitrance functions like a character in the story that humans tell themselves about their world. Mountains—and climbing—hold a privileged place in the imagination of the human, of the world, and of what counts as meaningful human action in the world. Perhaps humans are not geological, but rock is most definitely, intimately human, for better and worse.

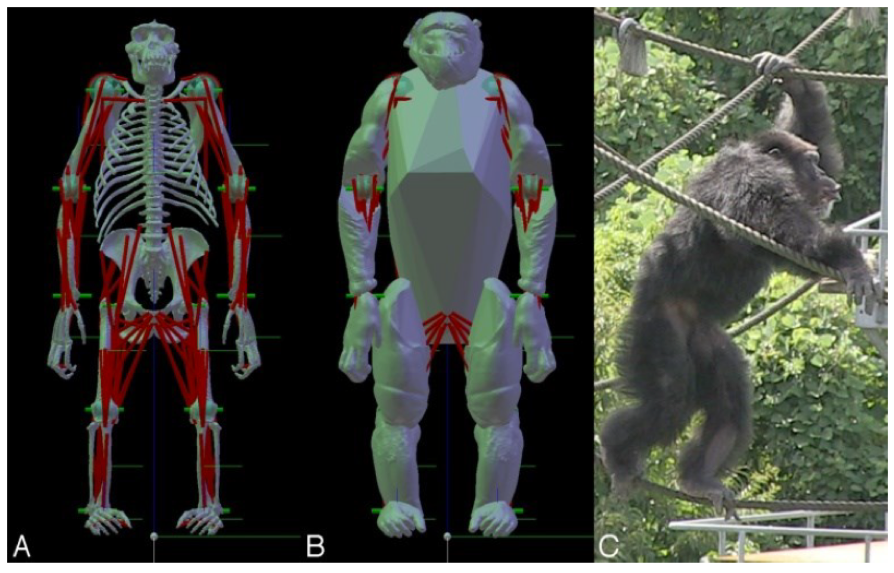

The climbing body is suspended somewhere between its prehuman origins and its posthuman future. Paleoanthropologists argue contentiously over the role of climbing in hominid evolution, examining the various possibilities for reading the histories of arborealism and terrestrial bipedalism in early hunter-gatherers.3 A new bioinspired climbing robot currently in progress, created by a team at the University of Genoa, is modeled on primate locomotion, because primates—all different kinds, from macaques to chimps—are the fastest and most efficient animals at climbing.4 Meanwhile, the liminal character of climbing—especially obvious at high altitudes, where the human body is constantly on the verge of its physiological efficiency—makes it a theater for the limits of the human and presages the coming stage of human development.5 It’s no surprise then, that interest in climbing continues to grow, both in active forms (commercialized mountaineering and climbing walls in university gyms and corporate offices) and passive forms, through an explosion of mountaineering literature and visual culture in not only advertising but cinema and social media.

The poster child for portraying climbing as more than human is the American pro rock climber Alex Honnold, whose rope-less accomplishments over the past decade seem actually impossible for a human body (and mind) to do.6 Free Solo, the 2018 documentary by Elizabeth Vasarely and Jimmy Chin about Honnold’s historic free solo climb of El Cap, which won the Oscar for best documentary feature, is a particularly useful text for thinking about the present cultural moment—a document not of climbing culture but of a culture in which climbing has taken center stage.

Even prior to El Cap, Honnold, already the greatest free solo climber in history, was fond of saying that the key to climbing is knowing when to quit—in the small sense, as in knowing when to go home for the day, but also in the larger sense, as in knowing when to stop altogether. This is the only way to survive a sport that is bound to kill you, sooner or later. Quitting is at the heart of the film’s happy ending, as Honnold looks squarely into the camera and announces, less than convincingly, that the next climbing achievement on that scale (but “bigger, cooler”) will be by “some kid” and probably not himself.

And yet the public swoons over the perceived madness of climbers, their refusal to stop, even in the face of enormous risks. The climber who keeps climbing is the one who upholds the public’s expectation of what motivates the activity in the first place, i.e., unstoppable, bottomless passion. When climbers fall to their deaths, which recently happened to another superstar of the sport, speed climber Ueli Steck, the public response is equal parts what did you expect?—as in the title of a New York Times opinion piece, “How Ueli Steck Met Mountaineering’s Oldest Companion: Tragedy”—and shocked disbelief—Steck’s body was autopsied, as if it weren’t possible that he might simply have slipped and fallen.7 Likewise, the two speed climbers who fell from El Cap in 2017 caused a media flurry of speculations of “overconfidence, miscommunication, and complacency,” as if falling while speed climbing could only result from error.8

Honnold himself is a great example of a climber who has achieved what he has precisely because he didn’t stop while ahead. In one oft-quoted piece of footage from an earlier film, of his soloing of Half Dome in 2011, he is momentarily paralyzed with fear on a ledge, so much so that he cannot move—forward or back—or even explain what’s happening to him. The film then cuts to him climbing happily to the top despite this minor setback. The whole premise of Free Solo is that to free solo El Cap is pure madness, to which everyone repeatedly attests, including his girlfriend (“it’s hard for me to grasp why he wants this”) and the other pro climbers in the film (one of his fellow El Cap specialists calls climbing with Honnold “a vice … like smoking cigarettes” and describes him as “the most likely to die”). As the film’s co-director and fellow climber Jimmy Chin ominously intones, “if you keep pushing the edge, eventually you find the edge.”9

Except that Honnold doesn’t. That’s the big take-away. Beneath Free Solo’s finger-wagging about quitting while one is ahead, including a discussion of Steck’s untimely death, flows a torrent of unstoppable passion to keep pushing the edge. But this bottomless human drive doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It meets its match in the bottomless recalcitrance of the mountains. It’s only together that they constitute the experience of meaning for which humans climb mountains, and which is perhaps the same thing as the depth “beyond all comprehension” that Brannen (rightly) refers to with awe.

In other words, if the climber’s desire is more than human, this is not only because it invokes bodies beyond human bodies but because it’s also always embedded in a particular environment. The so-called limits of the human body are never just bodily or just human—they always have terroir, if you will, an environment in which what is possible must always be carefully negotiated. This terroir itself is not merely geographical or material. The environments in question signify culturally and are imagined in particular ways.10 Their cultural meanings, just as much as their physical characteristics, shape what is and is not possible, and what in time becomes possible—in culture and imagination but also somatically, materially, and in fact. Desire, bodily limits, and environmental recalcitrance are inseparable from one another.

However, contemporary climbing culture is heavily inflected by big budget corporate advertising and visual culture, in which climbing is increasingly decontextualized from its environment. The accomplished climber presents the apex of not only physical but professional and financial achievement—the winner standing on top of the world. The message is that what matters is the climbing, not the mountain. A 2011 Citibank ad featuring top pro rock climber Katie Brown and Honnold playing a couple on vacation performs this logic brilliantly, with a voice-over that directly satirizes the objects of older credit card ads (shoes, belts, and engagement rings) and replaces them with the freedom that rock climbing ostensibly brings. While most “climbing rats” like Honnold built their careers while living out of cars and wholly rejecting a traditional life of work and wealth-building, this ad performs a sleight of hand in which one forgets what the ad is for: a credit card. The superimposing of climbing onto credit lines creates a certain fantasy of upward mobility, in which wealth and freedom are synonymous.

The glorious GoPro and drone footage, now par for the course in all corporate advertising that uses climbers and high-altitude mountaineers, has become a hallmark of what Dominic Pettman calls “the corporate sublime.”11 As the corporate sublime presents climbing-as-success, the image works to naturalize late capitalism itself, as if amassing wealth were the most natural, obvious, spiritually and environmentally integrated thing to do. As if it were freedom itself. And, perhaps most insidiously, as if it were inevitable. Baudrillard had his doubts about this aspect of mountaineering back in 1988, claiming that such practices effectively exhaust their own meanings because they are preprogrammed to succeed before they happen. It would never occur to anyone to attempt to climb unless they had decided ahead of time that it was, in fact, possible. Thus, when these ostensibly shocking ascents finally take place, they are, culturally speaking, “of no consequence.” He equates the Himalayan summits with the moon landing, which, he writes, has not revived the dream of conquering space but exhausted it.12

Of course, it’s counterintuitive to describe Honnold’s achievement as being of no consequence. But Baudrillard’s point is not about the effort, talent, work, and sacrifice required but about the cultural meaning of the achievement. The free-climb of El Cap—which Honnold describes as “the center of the rock-climbing universe,” apropos of space dreams—was culturally preprogrammed to succeed, and no one knows this better than climbers themselves. When Steck broke the record speed for climbing the Eiger North Face (for the second time), he seemed very happy, to be sure, but not the least bit surprised. Nor would it surprise him if that record were promptly broken by someone else, which he says immediately after breaking his own record, still wiping his very runny nose. It’s simply inevitable.13 Honnold, too, almost immediately following his victory, predicts that someone will soon outdo him. And this, on top of the fact that Free Solo is the first time such a massive mountaineering achievement has been filmed in real time, thus creating the uncanny experience of a film premised on the question Will he make it?—down to the nail-biting finale—when, in fact, everyone watching knows that Honnold did indeed make it.

As a document of the present, Free Solo is much more than the story of this particular climb or even this particular climber. It provides a framework for thinking about the complexity of the exhaustion of environments in late capitalism. That mountains get used up materially is not news, from the recent (and continuing) scandals around Everest to Himalayan warming and glacial melting. But what this film and this climb inadvertently show is that environmental degradation isn’t just material; it’s also cultural. The cultural meaning of environments is another “resource” humans use up. And we have not yet begun to theorize how these different aspects of environmental exhaustion and loss are connected, their particular dynamics of interplay, their shared logics, and their mutual dependence.

-

Peter Brannen, “The Anthropocene Is a Joke,” the Atlantic, August 13, 2019, link. ↩

-

Brannen, “The Anthropocene Is a Joke.” ↩

-

Vivek V. Venkataraman, Thomas S. Kraft, and Nathaniel J. Dominy, “Tree Climbing and Human Evolution,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 110, no. 4 (January 23, 2013), link. ↩

-

See Giovanni Gerardo Muscolo et al., “Towards a Novel Embodied Robot Bio-Inspired by Non-Human Primates,” Conference ISR Robotik (2014): 271–277. ↩

-

For this insight I thank Bartosz Kuźniarz, who likes to imagine a future in which pilot-less AI helicopters get together on the summit of Everest to hang out, occasionally reminiscing about the old days, when those weird creatures called humans climbed awkwardly to the summit and the helicopters’ own clunky ancestors were brought in for rescues and to transport dead bodies away, as well as occasional sightseeing tours of base camp for the wealthy. That such a fantasy is possible suggests that climbing, like intelligence, has a life of its own, beyond human bodies and human desire. And indeed, the mountaineering imaginary lends itself to such speculations. While humanoid AI robocopters are not likely to be the next chapter in the story of the climbing being, there’s no denying contemporary climbing’s posthuman flavor. ↩

-

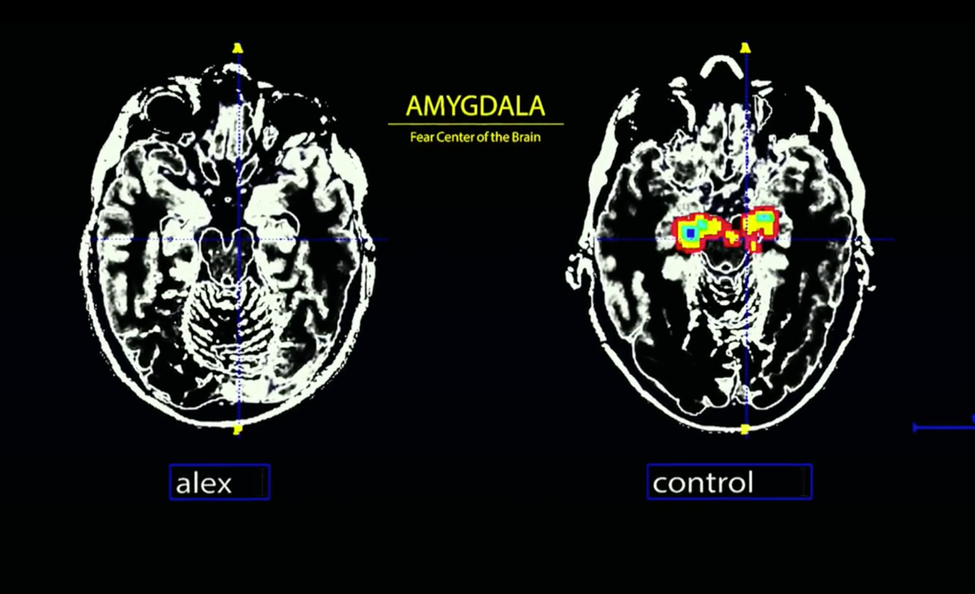

Free Solo shows Honnold getting an MRI of his brain so that researchers might understand the particularities of his amygdala, the brain’s fear center, which in Honnold appears to have a much higher threshold of stimulus than in the control subjects. ↩

-

Michael Wejchert, “How Ueli Steck Met Mountaineering’s Oldest Companion: Tragedy,” the New York Times, May 1, 2017, link. ↩

-

Peter Fimrite, “Witness Describes Death Plunge of Two Yosemite Climbers,” the Seattle Times, June 10, 2018, link. ↩

-

Free Solo, dir. by Elizabeth Vasarely and Jimmy Chin (National Geographic Documentary Films, 2018). ↩

-

Take, for instance, the extreme marathons set in different deserts around the world, like the 5 Deserts Marathon, which finishes dramatically in Antarctica. ↩

-

Dominic Pettman, Human Error: Species Being and Media Machines (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 2–5. ↩

-

Jean Baudrillard, America, trans. Chris Turner (1988; New York: Verso, 2010), 20–21. ↩

-

“Ueli Steck New Speed Record Eiger 2015,” November 19, 2015, link. ↩

Margret Grebowicz’s articles about mountaineering have appeared in the Minnesota Review, the Philosophical Salon, and the Atlantic. She is a professor of philosophy and environmental humanities at the School of Advanced Studies in Western Siberia and lives in upstate New York. She is the author of numerous articles and four books, including The National Park to Come and Whale Song, and is currently at work on a new book, Mountains and Desire.