For the 2019 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, the design firm TrasK House moved 528 truckloads of earth to build Kanye West a hill. The hill served as the stage for West’s two-hour “Sunday Service,” a medley of gospel, testimony, and rap. The service took place on Easter Sunday of Coachella’s second weekend. Recorded with a periscopic camera lens, West’s service was represented as a peek into a private moment. Despite West’s voice largely taking a backseat to the choir group led by the keyboardist Philip Cornish, the event was unabashedly on brand. Socks printed with “JESUS WALKS” and “CHURCH SOCKS” on them sold for $50. “HOLY SPIRIT” sweatshirts ran $225.

Variety’s headline for the event read “Kanye West Takes Coachella to Church with Easter ‘Sunday Service.’”1 Was tuning into the performance a chance to see one of the most fashionable artists of the twentieth century stray farther toward blasphemy or to witness a monumental production of gospel for secular fans? Each time the camera cut to the Coachella audience, fenced in below the performance, the stakes of Coachella reappeared—a grotesquely exclusive show of wealth that thrives on the cachet of cultural icons. (Did any artists play at 2018 Coachella besides Beyoncé?) “I was pretty disgusted with myself, I can’t lie—an hour earlier I’d gone out to a bodega to buy toilet paper in shorts and a hoodie,” Rembert Browne wrote for the Ringer, “walking past black families in glorious pastels, and now I was casting the Coachella YouTube channel on my television, watching a procession of black folk in brown two-piece baggy cheesecloth…”2 It was a you had to be there performance that presented the sacred at one of the year’s biggest spectacles. West’s long history of incorporating Christianity into his music still left the concert crowd nonplussed. It was as if West didn’t know if he wanted his fans to be participants or witnesses. Customers or churchgoers.

TrasK House’s hill emphasized the theatrical architecture inherent to gospel. The cultural discomfort produced by watching gospel at Coachella is in part a clash of celebrity and piety. What viewers witnessed was the transformation of a secular space into something approximating the pulpit with no precedent for crowd behavior. However, black artists performing gospel in secular space can be viewed as a distinct architectural tradition, one that has its roots in communal worship during antebellum slavery. To recount the narrative of gospel in secular space is to recover a history of enslavement and liberation, exclusiveness and publicness.

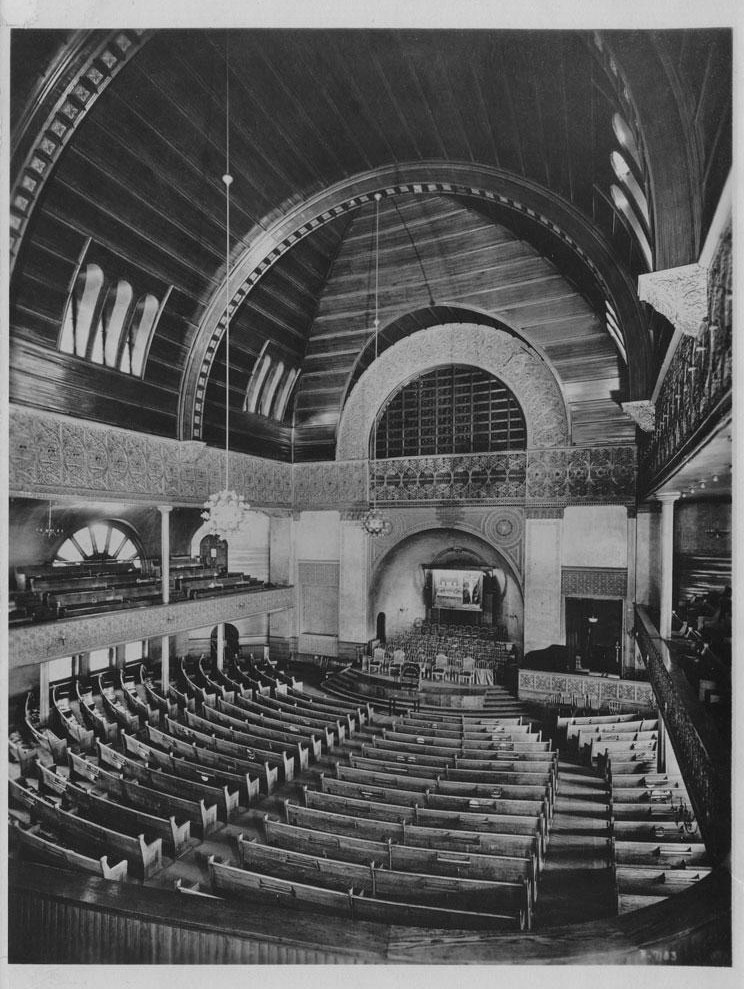

Today, the National Museum of Gospel is under development in Chicago’s predominantly black South Side—situated at the site of Pilgrim Baptist Church, which was partially destroyed in a fire in 2006. The original building, designed in 1890 by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, hosted the Kehilath Anshe Ma’ariv Synagogue. In 1922, the Jewish congregation left and a Baptist congregation moved in. Under the direction of Thomas A. Dorsey, the church gained the title, “Birthplace of Gospel.”3 Dorsey himself was a transplant from Georgia who had arrived in Chicago in 1916, a blues musician who had released records as Georgia Tom.4 Yet the mixture of secular space and spiritual energy at Pilgrim was there from the outset in what Amiri Baraka describes as the “blues impulse”: “That black emotionalism which came directly out of, and from as far back as, pre-church religious gatherings, the music of which might just be the preacher to congregation, in an antiphonal rhythmic chant-poem-moan which is the form of most of the Black group vocal music that followed: Preacher-Congregation/Leader-Chorus.”5 It was not necessarily the stained-glass and terra-cotta architecture of Pilgrim that set Dorsey’s choir apart in Chicago but the moans and hollers emanating from it—that, among certain individuals, even fellow preachers, were sounds undignified for Sunday services.

By 1921, the Chicago Defender lectured readers on the intolerable religious culture of migrants: “These religious enthusiasts do not seem to realize that residential neighborhoods are liable to have people living there who do not share with them in their demonstrative manifestations of religious devotion. Loud and noisy declamations and moans and groans from sisters and brothers until a late hour in the night are not only annoying but an unmistakable nuisance.”6 Dorsey figured the cry of the preacher in his choir as an invocation of the blues, the spirit of a musician working up the energy of a crowd: “[Listeners] cry it out. They cry it out. You can go up or you can drop; [you] can moan, see, you beg, then you express it. Let the folk wonder what the next thing is gonna be.”7 Dorsey’s tenure as choir director was marked by a sense of spectacle; a momentum of black expression that demands presence to be believed. The “shouting, clapping, and ring dancing” described by Michael W. Harris in The Rise of Gospel Blues, was a musical ritual harkening back to the services in the hush or “brush” harbors of the antebellum South:

Dorsey’s gospel choir reproduced an architecture that witnessed the rituals of black Americans historically uprooted and mistrusted as a crowd in public space. It is significant that Harris sees gospel as evoking the cries under slavery. How does the black community reestablish itself across time without reenacting the misery of slavery that made that community so particular to begin with? It’s a question that scholar Simone White responds to with a Fred Moten–inspired formula: “The covenant that makes our ‘thing’ a thing that can be apprehended is the promise to stay together in the absurd or ‘foolish’ space of the self that accepts itself as black, surrounds itself with blacks, a promise that is made and renewed by a self in ‘constant improvisational contact’ with other facets of the world.”8 Within the context of describing a black public, we can think of gospel as not only a musical performance but a forceful space-making activity critical to black identity. In his 1969 book Black Theology and Black Power, James Cone positions the black church as the sole identity-confirming space for slaves, orienting black power within the practices and architectures of Christianity. “The black church,” he writes, “was the creation of a black people whose daily existence was an encounter with the overwhelming and brutalizing reality of white power. For slaves it was the sole source of personal identity and the sense of community.”9

Distinct from sanctioned religious space, some slaves formed hush harbors, setting a precedent for black communities to construct personal sacred sites despite the hostile conditions around them. The hush harbor created a space impenetrable to, or cloaked from, the white supremacist state—out of shelters sealed with untrimmed branches and supported by wood beams and posts. A 1938 account by former slave Thomas Cordelia clarifies some of the autonomy of hush harbors: “White folks brought deir slaves and all of ’em listened to a white preacher from Watkinsville named Mr. Calvin Johnson. Dere was lots of prayin’ and shoutin’ at dem old brush arbor ’vival meetin’s.”10 Other accounts from interviews by the Works Progress Administration in Georgia mentioned black preachers, suggesting religious life among slaves was a mix of obligation, supervision, and transgression. Charles Grandy, a slave in Hampton, Virginia, describes the cries in the harbors: “Used to go ’cross de fields nights to a old tobacco barn on de side of a hill. Do’ was on de ground flo’, an’ you could climb up a ladder an’ step out de winder to ground on de other side. Had a old pot hid here to catch de sound. Sometimes would stick yo’ hand down in de pot if you got to shout awful loud.”11

In 1831, Alabama made it illegal for blacks to preach. Born a slave in 1737, Andrew Bryan is one of the first documented preachers to inhabit hush harbors. While enslaved, Bryan was ordained in 1788, preaching to black and white congregations. “Andrew…and his brother Sampson were, upon the complaint of their traducers imprisoned and dispossessed of their meeting house.”12 The brothers moved from swamps to barns to private homes. In 1794, Bryant founded the first black church in Savannah, now dubbed the First African Baptist.13 It stands today in gray stuccoed brick.

Empirical accounts of worship under slavery help establish a physical transformation of black religious space—from the architecture of harbors to the watch of slave masters to the autonomy of a church founded by an ordained black preacher. Out of an expanding black Christian community came a white fear of the potential for affective speech to mass audiences; a fear of slaves gathering and finding community in the church was in part a fear of losing supremacy over the built environment. Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s account of the growth of black churches in the United States describes the rise of black preachers as a turning point in the racial hierarchy. In cases of runaway slaves, a correlation is made between freedom, the public figure of the black preacher, and the church:

The escape of a young Negro, a slave of Thomas Jones, in Baltimore County in 1793 is a case in evidence. Accounting for his flight his master said: “He was raised in a family of religious persons commonly called Methodists and has lived with some of them for years past on terms of perfect equality; the refusal to continue him on these terms gave him offense and he, therefore, absconded. He had been accustomed to instruct and exhort his fellow creatures of all colors in matters of religious duty.” Another such Negro, named Jacob, ran away from Thomas Gibbs of that same State in 1800, hoping to enlarge his liberty as a Methodist minister; for his master said in advertising him as a runaway: “He professed to be a Methodist and has been in the practice of preaching of night.” Still another Negro preacher of this type, named Richard, ran away from Hugh Drummond in Anne, Arundel County, that same year, while another called Simboe escaped a little later from Henry Lockey of Newbern, North Carolina.14

These records highlight the link between religious practices and emancipation as well as the coded performance of the black preacher—a public figure that threatened the hierarchical stability of leadership in slave society. As Harris described, black preachers merged folk traditions with liberation.15 The cries of twentieth-century church gospel are descendants of this tradition.

The sense of urgency and so-called indignity exhibited by gospel choirs suggests a cultural power within the church beyond theology. Playwright Carlton Molette describes the black church service as a “soulful” ritual drama—one that is “emotionally or spiritually motivated rather than rationally motivated.” Music, dance, and speech, which Molette calls “valid and useful tools” for this drama, extend the emotional or spiritual life of the church in public and secular space. Ritual is defined by Molette as “performance—in and for a community—that attempts to alter the values of that community.”16 The audience plays a key role in this ritual; rather than sitting passively at attention, the audience of ritual drama in black theater are participants in the rise and fall of action on stage. Molette’s description reiterates the duration of interaction between participants:

Spiritual intensity hinges on the action of the “audience,” which Molette is sensitive to put in quotes.17 Molette does this not to imply the word is superficial—nor to question the crowd as a cohesive unit—but to suggest that the formal use of “audience” in black ritual includes a participation not evoked by audience in the canon of Western straight plays. Molette is describing a form of audience engagement that comes from another tradition entirely.

One way to describe immersive theater is to say that without an audience, the performance could not exist. It is this power configuration, the audience enacting ritual, that relates the black church to performance in secular space. James Baldwin’s reflection on his church experience articulated the sensitivity to duration and drama.18 He writes in Letter from a Region of My Mind, “being in the pulpit was like being in the theatre; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked.”19 For Baldwin, the benevolence of a Christian service was bounded within church walls. “When we were told to love everybody, I had thought that meant every body. But no. It applied to those who believed as we did, and it did not apply to white people at all.”20 The participation described by Baldwin is part of a larger relation between architecture, belief, and the audience ritual (space and time). When viewed at Coachella, outside of church walls, this performance is uncomfortable. Yet this public gospel is part of a cultural genealogy of sacred black space in America, a legacy of architectures adopted, camouflaged, and converted.

The playwright Jeremy O. Harris integrates all three of Molette’s ritual components—music, dance, and speech—into his work. Harris’s narratives use the stage as a site of black liberation through compulsive expression. They are staged therapies. During an interview with the New York Times, Harris described his 2019 play Daddy as a “love letter to his mom,” adding that the addition of a gospel choir was to keep her attention: “It’s all the spectacle I want to see in the theater.”21 A gospel choir stands as a narrative voice in Daddy—both a theatrical reference to ancient Greek chorus and application of praxis clearly rooted in black culture. The choir appears in the background, communicating with characters, at times, not audible to the audience. The choir first appears during a scene in which the mother in the play, Zora, calls her son Franklin. The choir responds in song, restating Zora’s lines and voicing her unspoken sentiments. During a climactic wedding scene, Zora performs a rendition of Shirley Caesar’s song “Satan, You’re a Liar.” She is backed by the choir, delivering a message not only to the characters but to the audience who have now become congregates to Harris’s gospel. Harris’s latest, Slave Play, reenacts another confessional site under the secular gaze of academics: “Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy.” Somewhere between mockery and sincerity, Harris’s characters rehearse racial violence in America and how to survive its traumas.

Arthur Jafa’s 2018 exhibition air above mountains, unknown pleasures at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in Harlem featured the video piece akingdoncomethas, a one-hundred-minute-long montage of black church sermons and gospel performances. The press release describes the video as staging “black pocket-universes of intense energy, eloquence, and illumination.”22 Jafa relies on archival footage to communicate these scenes of black Christian worship and performance, some of it still bearing watermarks. The artist does not prioritize high fidelity but instead emphasizes the cultural assemblage of his subjects. The video approximates the duration of a church service, but the footage is always excerpted, perpetually cut, suggesting that the audience at Gavin Brown is never meant to experience the video as a stand-in for the real thing.

Jafa’s montage focuses on the choreography and the fluctuating tone of the preachers, opening with a 1974 performance by Al Green on Soul Train of “Jesus Is Waiting.” The artist’s editing makes clear the diversity of black ritual spaces and the entanglement of black worship in pop culture. The Soul Train studio audience has all eyes on the stage as Green takes them through a Lord’s Prayer, leading into a testimony lasting over seven minutes, his right arm suspended in a sling, his left hand glittering with diamond rings. Ritual is on full display as performance: profane and ephemeral, site-specific movement. Soul Train’s format, structured around musicians and dancers, depicts black expression as much for itself as for a distant television viewer. The obvious discrepancy between the gallery audience at Gavin Brown and the congregation is the lack of synchronized energy. While Gavin Brown has a history of exhibiting black artists, it struggles to overcome the atmosphere of any gallery, in which visitors fall into a quiet, touristic demeanor.

The gallery precludes an audience that contributes to the language of gospel, instead responding to sermon and prayer with silence. However, ritual drama can allow artists to subversively double-cast an audience as participants in the art and the ceremony. The artist Steffani Jemison references the spiritual literacy of performance within the black church in her 2017 video Sensus Plenior. Shown at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, the piece features the Reverend Susan Webb of the Master Mime Ministry of Harlem. Webb paints her face white as she practices her expressions in the mirror. The silent performance is accompanied by a score performed by violinist Mazz Swift and double bassist Brandon Lopez. In the context of a church service, the Mime Ministry performs to gospel. Jemison slows Webb’s performance down, abstracting her movement from the service of gospel to a language of cinema and dance. Similar to Jafa’s video work, Jemison produces a study of black ritual and a space for black people to believe inside a secular institution.

When interviewed about his latest work The White Album, for which he received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, Jafa said he wanted to move away from giving audiences a “microwave epiphany about blackness.”23 Akingdoncomethas is a response to his suspicion that audiences receive catharsis too easily. “The liberty of men is never assured by the institutions and laws that are intended to guarantee them,” says Foucault. “This is why almost all of these laws and institutions are quite capable of being turned around. Not because they are ambiguous, but simply because ‘liberty’ is what must be exercised.”24 Even in silence, the theatrics of liberation cannot be overstated. The architecture of gospel appears in perpetual motion, contouring to the identity of the performers and the audience. The motion is, in Simone White’s criticism of black identity, in always renewing contact with the world. Or, as a friend once told me: you could read Fred Moten on black life as performance or you could just go listen to the rapper Vince Staples.25 Vince “plays or practices a game which is also the game of repeating what we already know,” writes White, “repeating facts to which it is possible to nod our heads, facts such as ‘the music and people is the same.’”26 In repetition, what appears as fact will not be legible to all.

If there is an architecture of gospel, it is assembled in the moment of performance, an architecture measured by volume and duration. In a 2017 interview with Ben Lerner, Jemison spoke of the contemporary art world myth of a neutral audience, universally literate outside of Western traditions: “Blackness is critically positioned in one of two ways: as excessive to ‘the work’ or as a stain on it. Either can be profoundly destabilizing.”27 The presence of gospel in contemporary art does the opposite of presuming a universal audience, instead it compels viewers to study their own relation to black ritual. The modular staging of gospel tends to lay bare, even if it doesn’t reach the back of the house, the long cries of liberation.

-

Jem Aswad and Erin Nyren, “Kanye West Takes Coachella to Church with Easter ‘Sunday Service,’” Variety, April 21, 2019, link. ↩

-

Micah Peters and Rembert Browne, “Through the Fish-Eye Lens: On Kanye West’s Sunday Service,” the Ringer, April 22, 2019, link. ↩

-

Blair Kamin, “Plan to Revive Pilgrim Baptist Church Shows Promise but Faces Hurdles,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 2019, link. ↩

-

Amiri Baraka, Black Music (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), 203. ↩

-

Michael W. Harris, Rise of Gospel Blues: The Music of Thomas Andrew Dorsey in the Urban Church (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 186. ↩

-

Harris, Rise of Gospel Blues, 181.

Dorsey’s newly formed gospel chorus could be considered a new singing Band, but in a resurrected version: as the gospel chorus it had become an institution within the very church in which it had been considered not to have a part. The desire among black Americans, it seemed, had never been to assimilate non-traditional worship practices to the point that they would obliterate the root black religious experience, slavery.[^8]

-

Simone White, “Descent: American Individualism, American Blackness and the Trouble with Invention” (Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, 2016), 158, link. ↩

-

James H. Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018), 92. ↩

-

“Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves Georgia Narratives, Part 4,” Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project 1936–1938, vol. 4, part 4 (Washington, DC: Works Progress Administration, 1941), link. ↩

-

Harris, Rise of Gospel Blues, 182. ↩

-

Carter G. Woodson, The History of the Negro Church (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1921), 49, link. ↩

-

“First African Baptist Church: Our History,” First African Baptist Church, link. ↩

-

Woodson, The History of the Negro Church, 72. ↩

-

“As a bluesman/preacher, Dorsey, through his ivories and with [E. H.] Hall as his surrogate voice, assumed the role in church that he had cultivated so well in the hole-in-the-wall blues joints—that of eliciting a collective response through the declaration of his personal feelings.” See Harris, Rise of Gospel Blues, 185. ↩

-

Carlton Molette, “Ritual Drama in the Contemporary Black Theater,” the Black Scholar, vol. 25, no. 2 (1995): 24, link.

Conflict through plot complication is not necessary, since there are other devices available to increase the intensity. The spiritual intensity eventually reaches the point of climax, causing an emotional release among members of the congregation, or the “audience.” However, this point of climax and emotional release may occur at different points in time for different members [of the] congregation. Structurally, the peak of emotional intensity is followed by a gradual reduction of spiritual intensity; this reduction cannot be called a denouement, since its purpose is not to resolve conflict nor tie together all the loose ends of the plot.[^18]

-

Molette, “Ritual Drama in the Contemporary Black Theater,” 26. ↩

-

James Baldwin, “James Baldwin: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” The New Yorker, January 3, 2019, link. ↩

-

Baldwin, “James Baldwin: Letter from a Region in My Mind.” ↩

-

Baldwin, “James Baldwin: Letter from a Region in My Mind.” ↩

-

Naveen Kumar, “A Playwright Who Won’t Let Anyone Off the Hook,” the New York Times, November 28, 2018, link. ↩

-

Greg Tate, “Arthur Jafa Air above Mountains, Unknown Pleasures,” Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, link. ↩

-

Ruth Gebreyesus, “Why the Film-Maker behind Love Is the Message Is Turning His Lens to Whiteness,” the Guardian, December 11, 2018, link. ↩

-

Michel Foucault and Paul Rabinow, The Foucault Reader (London: Penguin Books, 1991), 245. ↩

-

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe, NY: Minor Compositions, 2013). ↩

-

White, “Descent: American Individualism, American Blackness, and the Trouble with Invention,” 187. ↩

-

Ben Lerner and Steffani Jemison, “Steffani Jemison by Ben Lerner,” BOMB magazine, May 15, 2017, link. ↩

Thuto Durkac-Somo is a graduate of Columbia GSAPP’s Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices program. His writing on the art and technology of video cameras has appeared in Real Life Mag.