At this year’s Lisbon Architecture Triennale, we received, if not a preview, then perhaps an offering from the intellectual activity surrounding Rem Koolhaas’s exhibition on the countryside, slated to open in early 2020 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Curated by French architectural historian Sebastien Marot, “Architecture and Agriculture: Taking the Country’s Side” was held from October 5 to December 2 at Garagem Sul, a gallery space buried within the fortress-like Centro Cultural de Belém complex a few miles west of central Lisbon. Marot’s previous work on the countryside includes his research on O. M. Ungers’s 1977 manifesto, “The City in the City—Berlin: A Green Archipelago.” He recently taught with Ungers’s co-conspirator Rem Koolhaas, and much of the research from this exhibition seems to have derived from this pedagogical exercise. Koolhaas’s “Countryside” awaits unveiling, but both exhibitions share the conviction that if architecture and design is to have a role in addressing climate change, it will necessitate a focus upon the rural.

Marot’s exhibition is thoroughly researched and highly textual—the experience of walking through the gallery is not unlike walking through an exploded book. Within this book, one encounters various episodes of intersection between architecture and agriculture. Firstly, Marot argues a co-origin for agriculture and architecture, as the development of agricultural cropping in the Neolithic era coincided with the construction of permanent buildings. Furthermore, he makes a provocative suggestion about the closeness of agriculture to architectural theory, by highlighting that one of the best-preserved copies of the seminal architectural theory book, Vitruvius’s De Architettura, was bound together with an agricultural treatise by Varro. The excavation of these origins serves to establish a foundation within human and architectural history from which to argue the imbrication between agriculture and architecture.

However, as the exhibition proceeds, the works collected in Marot’s research show that there has been little sustained discourse on agriculture within architectural theory and that architects have not historically designed in agricultural contexts. Instead, the encounters between agriculture and architecture have been sporadic and marginal over the centuries of architectural history surveyed. The collection of material resembles a cabinet of curiosities, a dazzling array of eclectic projects with little historical continuity, organized by its own idiosyncratic taxonomy.

The layout of the exhibition is modeled on the form of a cathedral or basilica. It is a discreet space, guarded by a riff on a phrase at the entrance to Plato’s Academy: “let nobody here enter who is ignorant of the scale and proportions of our biosphere.” The exhibition is a container of sacred knowledge, in which the visitor mines existing histories for new meanings and coded messages. The proposition here is that from the heterogenous material of the past, it becomes possible to see how to proceed in the future and to understand the agency of architecture in climate crisis.

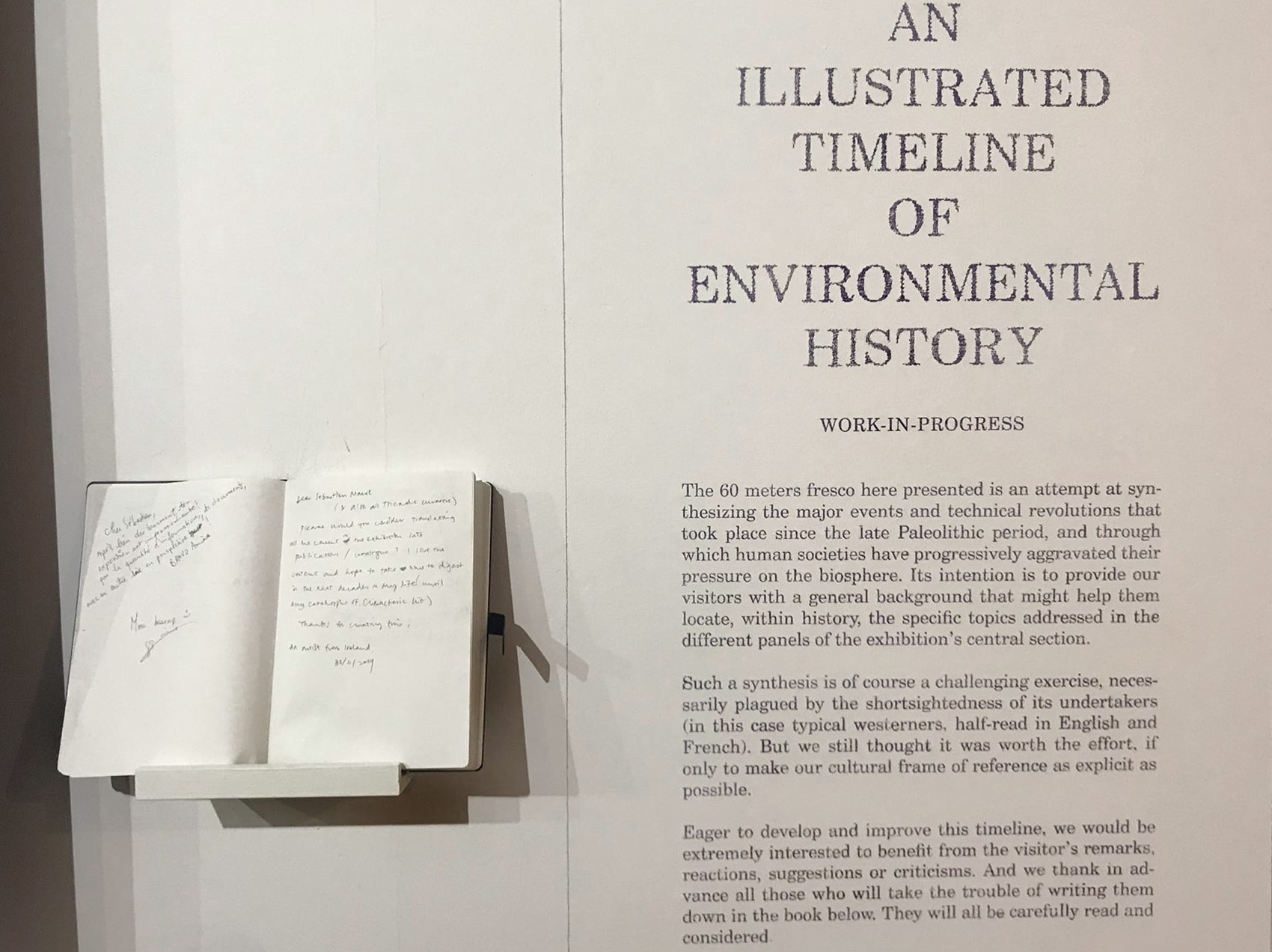

The visitor is greeted by three large entrance panels, followed by a “nave” of suspended panels arranged in a grid, which terminates in a “choir” of four panoramic views of the future that face a central seating area. Along the sides are two “aisles”: on the left wall is a printed timeline, a “common history” (as the curator describes it) from the Neolithic to the present, while the right side has four viewing “chapels” of video material. Marot acknowledges in introducing his timeline that his history is one reliant on a printed history with French and English bias.

Perhaps conscious of how heavy in text the remainder of the exhibition will be, it opens with three suspended panels whose images present themselves without textual explication. The first panel shows excerpts from a set of allegorical fourteenth-century frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, depicting good and bad government through their modes of resource management (although actual methods of statecraft remain beyond representation). The next panel offers two illustrations of what this management could look like. One is a seminal image of urban planning, Patrick Geddes’s early twentieth-century “valley section” diagram, showing the spatial distribution of productive activity. The other is an image from popular culture, a projection of a technomodernist farm of the future printed in National Geographic in 1970. The third panel shows a range of threats to the rural landscape. Clifford Harper’s illustration for the British countercultural journal Undercurrents, showing a pastoral utopia surrounded by the threat of agribusiness and military-industrial technology, is printed on one side. On the verso is a photograph of a bucolic farm stand in Connecticut with a burning house in the background, suggesting that while domestic shelter fails, the agricultural market remains standing. The image of the burning building and the mapping of agricultural labor across a landscape are repeated in various ways in these three opening panels, and they correlate with two major motifs throughout the exhibition: environmental crisis, and resource management as a primary mode of response.

The central argument that Marot relays to the visitor is found in the nave, in a grid of forty-two suspended panels divided into six themes. Each theme is organized in historical sequence and begins with the left-most panel, such that one moves through the exhibition like a typewriter changing lines. The white face of the panels is heavily textual and resembles the spread of a book. As one “changes lines” to begin the next theme, the verso of the just-read panels becomes visible. Each shows a single image of an architectural project, which is at times related and at others completely unrelated to the text on the other side. Images are displayed together in a way that allows the viewer to understand and draw their own inferences from the aesthetic landscape of the material, but as Marot himself claims, he avoids drawing conclusions as to what the total collection of material demonstrates.

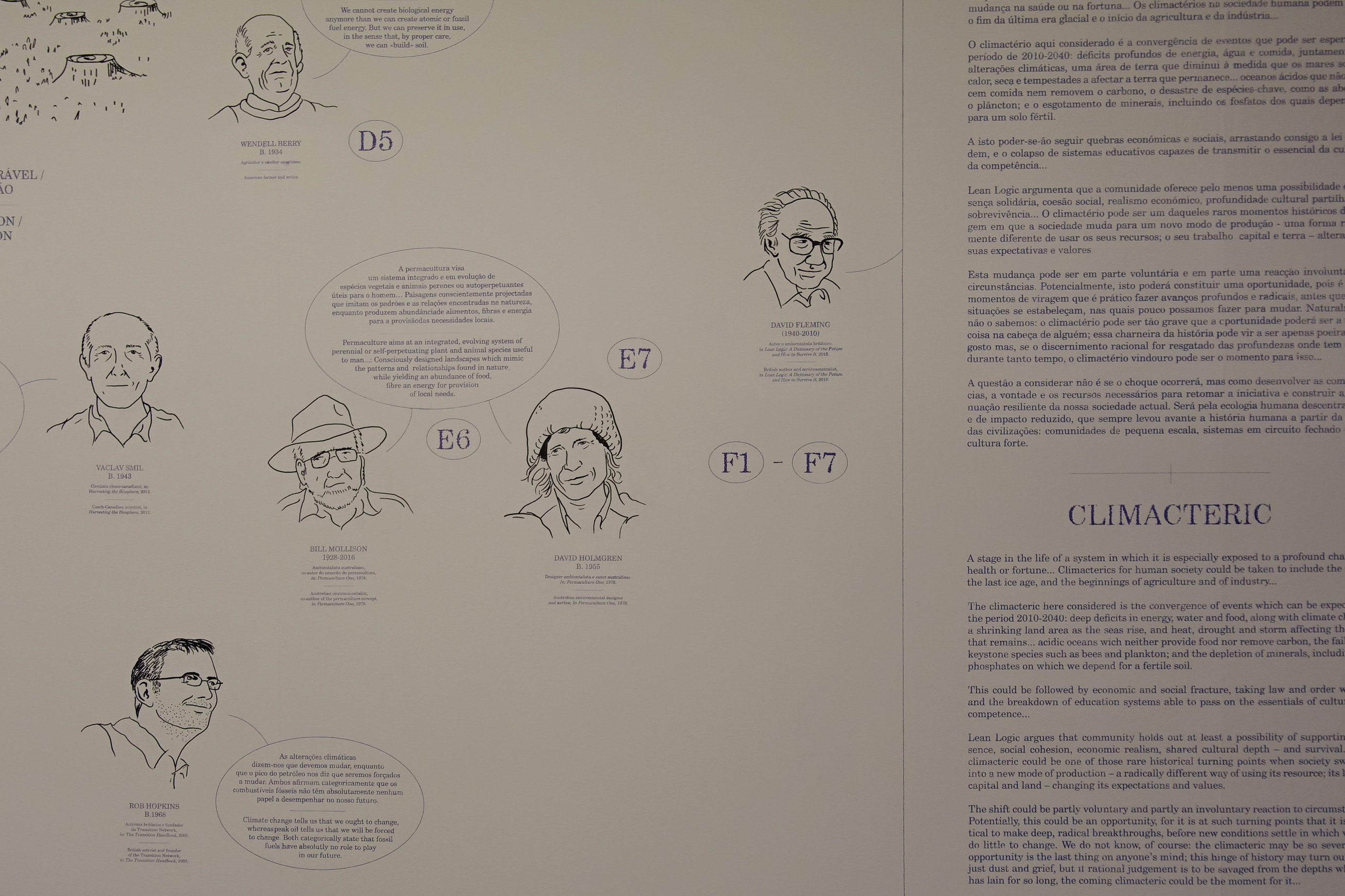

However, if there is a curatorial conclusion, it would be the exhibition’s evident support for permaculture—the design of self-sustaining agricultural ecosystems around human housing. Marot describes it no less than the most “consistent theory of design” since Vitruvius and Alberti. David Holmgren and Bill Mollison, the originators of permaculture in the 1970s, are presented at the end of the timeline, suggesting their work points to the next phase of the “great common history” on display. Hours of footage from Marot’s interviews with Hopkins and Holmgren are screened in the viewing “chapels” on the right side of the exhibition.

While permaculture is primarily an agricultural system, architectural tools like sectional drawings are used to “design” growing systems. It is this architectural mode of work that separates permaculture from conventional agriculture. The panels highlight the work of permaculture teacher Patrick Whitefield, for example, who identifies conventional agriculture as operating from an aerial view. In comparison, sectional drawings illustrate how permaculture principles design agricultural systems in a volumetric way. Permaculture bears conceptual resemblances to the housing designs of the 1960s and ’70s that attempted to integrate small-scale agriculture into urban and domestic contexts—many examples of which are found in the exhibition, such as the Integral Urban House by Sim van der Ryn and the Ark by the New Alchemy Institute.

What, then, has changed in the last fifty years since these projects were carried out? One key change is a shift in ecological discourse, which now more fully recognizes the planetary scale of environmental degradation and the climactic extremes that increasingly enter the experiences of everyday life. While Holmgren’s models are projected as the way forward, his principles were primarily developed in the late 1970s in the temperate climate of Tasmania and Melbourne. As such, the question remains open as to whether provisions are only available in places with a stable environment, while offering little resilience for places affected by climactic extremes.

The characterization of permaculture as the most consistent theory of design since Vitruvius and Alberti reveals some biases, or at least habits of thought, about the nature of design theory. Like the treatises of Vitruvius and Alberti, the principles of permaculture as presented in the exhibition are communicated in published, written form, by single, largely male figures. From the lens of architecture, it is clear that the discipline continues to struggle to recognize work that is authored communally and is practiced rather than published. The final panel of the nave section of the exhibition concludes with the observation that David Holmgren has collected a bounty of examples showing that the most successful permaculture experiments have been carried out by “permaculture pioneers” in suburban Melbourne. The elevation of these “pioneers” is particularly troubling given the thriving immigrant culture of backyard agriculture in the Australian suburbs, which pre-existed Holmgren’s writings and goes unremarked on here. Postwar European migrants created agricultural systems in suburban lots, replacing lawn with food production.1 They planted fruits, vegetables, and herbs to bring the food of their homelands to their new antipodean home. Thousands of miles of ocean separated them from their previous familial and social ties, but new communities could be formed through the common memories of food and crops. Consistently overlooking this type of history in favor of endorsing single figures like Holmgren, the exhibition limits its imagination when it comes to the theories of design that can bring us into the future.

The final panel on adaptive suburban development prepares the visitor for what is described as the seventh and final thematic section, the “choir” formed by four inward-facing panels with commissioned drawings by the French cartoonist Martin Étienne. Faced by seating that gives respite from the lengthy section of panels prior, these images are intended to encourage contemplation of the future and serve as a type of conversation piece. Although the drawings are described as “competing visions” rather than offering disparate alternatives, they resemble four stations along the same spectrum of urban density and technological utilization.2 Titled “Incorporation,” the panel showing the furthest extreme of technomodernism depicts skyscrapers filled with crops and animal lots. While cars, trucks, and speeding jets crisscross the landscape, humans are only found in picturesque parks, which have moved into the interior of high-rise buildings. On the other end of the spectrum, the panel titled “Secession” shows wind turbines alongside horse-drawn plows, while a riverside city remains indistinct in the distance. In the sky, a single hot-air balloon slowly ambles by. Given Holmgren’s suggestive comments that the suburbs have been the most successful site for permaculture, it is the two middle panels that seem to endorse the way toward the future. These drawings are described as showing proposals at the urban edge, with “Negotiation” showing a more intimate integration of agricultural program into residential spaces, such as rooftops, backyards, traffic circles, and road embankments. In “Infiltration,” residential and office buildings are more clearly delineated from greenhouses and animal lots.

Étienne’s drawings recall a reference from the beginning of the exhibition—the drawings of Clifford Harper.3 Harper made a series of drawings for the 1976 book Radical Technology that depicted six sites of labor, proposing a new relationship between people and waste and energy consumption. This included a design for an agricultural system for urban terrace housing that bears resemblance both to Holmgren’s permaculture experiments and Étienne’s drawings. Harper’s drawings have a significant difference, however, in the scale and subjects depicted within his utopic projections. They are particularly notable for showing a majority of the workers as women, an alteration that Harper made after early criticisms that there were too many male figures in his drawings.4 These drawings were printed as a set of posters in the late 1970s and the images of women working in mechanics shops, wood workshops, and gardens became part of a political and social stance that accompanied their ecological vision.

In Étienne’s drawings, however, the human figures have no faces, no gender, and few characteristics to determine their social and political lives. His worlds are drawn in blue pencil and only colored by green, foregrounding plant growth while the world surrounding them fades without detail into the background. The blue and green give the impression of absolute cleanliness despite the visceral smells and sounds that would emanate from a world where cattle graze right alongside picnic tables and sheep live in the confines of a traffic circle. While some people are playing basketball and riding bikes, others are working in the fields. These generic figures have no history or cultural delineation. If these drawings are intended to be provocations for considering our ecological future, it is important to consider how the manner of representation modulates possible conversations. Rather than naturalizing social and labor conditions within these representations, it is precisely in these frictions where invaluable dialogues can take place about who gains and who suffers in climate crisis.

If we want to address the power relationships within agriculture and aesthetics, it is invaluable to consider the labor of forming such landscapes. When English settlers landed in Australia in the eighteenth century, they marveled at the bucolic beauty that they encountered. With its rich, loamy soil and tamed vegetation, they believed they had discovered a land that naturally resembled a country estate. Without the domestic architecture of a country seat, they believed it was owned by nobody, terra nullius, and thus failed to recognize the stewardship of the Aboriginal inhabitants on the land. Within a few years, their naiveté became apparent as the hoofed animals they brought from Europe pounded the delicate soil into a hard clay, making it unarable and barren. What they saw as naturally occurring pastoral land had, in fact, been carefully cultivated for thousands of years by Aboriginal tribes using a well-established culture of complex agricultural techniques, who had since been driven from their lands.5

Pastoral aesthetics are a powerful lens through which our surrounding environment is represented and may well be compelling drivers for urban and ecological change. But the pastoral landscape is not a passive site of aesthetic appreciation—it is an active site imbued with technological and scientific methods of environmental management. This exhibition illustrates how architecture has historically played a role in environmental and resource management, thus altering the agricultural landscape. The tools of architectural practice can indeed be applied to agricultural and ecological thinking, but the discipline can also offer tools beyond resource management. The telling of architectural histories, for example, can reveal how landscapes were designed and constructed, and to what ends.

The compendiousness of this exhibition brings into focus the shortcomings that continue to haunt the architectural discipline. In drawing a great timeline of “common history,” Marot acknowledges the incompleteness of such an exercise and offers a comments book as an apologetic move in compensation for the exhibition’s reliance on Western historiography. Indeed, the most important story may lie in the comments book itself. The formative sites for climate change will likely not be in the capitals of Western histories, even if summits and agreements are named for them, but in landscapes of extreme exploitation under the logics of productive extraction. The Industrial Revolution is presented as a starting point in the creation of the environmental conditions that this exhibition addresses. Although it may have begun in the cotton mills of England, it did not remain there for long. Industrial production has far vaster effects in its colonized landscapes, as their environments were and continue to be altered for trade, resource exploitation, and manufacturing. It is not the origin point that matters but the history that unfolded afterward. The binding together of De Architettura and De Re Rustica is a curiosity—the productive relationship between architecture and agriculture remains an ongoing history.

-

Australia did not have an active battlefront within its own borders during WWII and was a place to settle after the widespread destruction of European cities and landscapes. As it was close to the significant Asian war front, however, Australia had an immigration policy barring non-white refugees. The White Australia Policy was not lifted until 1973. While there was xenophobia toward European postwar migrants, by the 1980s when Holmgren and Mollison were forging their permaculture work, these backyard agricultural systems had been naturalized into Australian suburbia. ↩

-

The structure of this sequence of panoramas bears some resemblance to Thomas Cole’s series of landscape paintings from the 1830s, The Course of Empire. These paintings depicted the transition from an imagined primitive state to an imagined future of imperial excess and destruction, framing the ideal state of pastoral democracy at its center. ↩

-

One of the opening images of the exhibition is Harper’s drawing for the journal Undercurrents. The editors of Undercurrents published the book Radical Technology. See Peter Harper and Godfrey Boyle, Radical Technology (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976). ↩

-

Peter Harper, “The Early Life and Work of Anarchist Artist and Illustrator Cliff Harper,” presentation for Radical Technology Revisited conference, Bristol University, September 2–4, 2016. ↩

-

Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu, Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (Broome, Australia: Magabala Books, 2014). ↩

Jessica Ngan is a PhD candidate in the history and theory of architecture at Princeton University. Her dissertation examines the role of rural and agricultural technologies in architectural practices of the 1960s and ’70s in the United States.