We are living in the future

I’ll tell you how I know

I read it in the paper

Fifteen years ago1

On what would have been federal tax day in the United States, thousands of car-bound Michigan protesters converged on the streets surrounding the Lansing capitol as part of what organizers called Operation Gridlock.2 Rallying against elements of the governor’s response to the novel coronavirus public health crisis, their demands have since been echoed in physically distanced form across the country.3 The individuated automobility of these events—sharply contrasting with the centralized, fixed urban presence of the capitols, detention facilities, and other targeted architectures of state power—has an unmistakably geopolitical valence. But the where of these protests isn’t as straightforwardly coded as their most extreme cases, or their more familiar interpretations, continue to promote.

Under current conditions, isolation at home translates with relative ease into the car, at least for those who have them both. And whether that car is crossing the Australian outback, traveling through a tunnel in downtown Moscow, or protesting in a midsize Michigan town, the spatial—one might say urban—experiences of its riders are bound to be at least somehow comparable.

Though now physically closed to visitors, the uptown Manhattan exhibition that continues to occupy the entirety of Frank Lloyd Wright’s ramping rotunda aims at a rebalancing of these urban imaginaries. A riposte to elite, city-dwelling and city-studying tastemakers everywhere, it asserts: they’ve been looking the wrong way. Into the throes of this country’s presidential contest—in its persistent, socially distanced anguish over the predilections of the white, working, swinger class—wades the Guggenheim with the news alert that “the countryside is not pure, but at least its struggles are more ‘real.’”4 Leading the charge is the architect Rem Koolhaas, shining a bright light on his last curiosity, which is meant to be every architect’s next.

Over the course of the last decade, a host of employees, students, independent collaborators, and museum staff have been brought into Rem’s rural fascination, ultimately yielding, as he put it, the “pointillist portrait” “about the absolute opposite of New York” plowing out onto a now empty Fifth Avenue in the form of a hi-tech tractor.5 Together with its accompanying publication (“not a catalogue”),6 the exhibition (“not an art show nor an architecture show”)7 is full of interesting stories worth telling. Anchored in the oft-cited early-2008 UN declaration that by the end of 2050 nearly 70 percent of the world’s population would live in urban areas,8 visitors are given a glimpse of “space[s] on the earth outside the city” ranging from blockaded Qatar and exurban Amsterdam to pre-revolutionary China and post-internet Nevada.9 These stories, though, are about much more than the countryside. Within the concept itself, and indeed born out in many of the show’s vignettes, lies important nuance that the rigid curatorial framing and overloaded approach to display unfortunately work to undermine.

“Too big for containment in a book,” according to Koolhaas, the exhibition—co-authored by Samir Bantal, together with a large research team from multiple institutions and a curatorial team at the Guggenheim led by Troy Conrad Therrien—nevertheless functions largely in the form of a book in the round.10 After a collection of introductory frontmatter and historical overviews anchored in comparative Roman and Chinese notions of the non-urban, the display proceeds up the ramps and through the last two thousand years. Text- and video-filled chapters on curtains and vinyl chronicle drives to drop out, real estate of wellness and retreat, massive military and agricultural mobilizations, and rapidly disappearing permafrost, among many other topics.

A video project led by Ingo Niermann titled “Sea Lovers” is a highlight due both to its sharp, sideways embrace of the undefinable space between urban and rural (made possible by moving off land entirely) and, relatedly, its nuanced poignancy, which is a respite from the exhibition’s otherwise relentless approach. Niermann’s gentle exploration of the sea’s corporealities is both exciting and necessary, the limbs of his wave-washed dancers embodying a critique of the dominance of property seen elsewhere on the ramps.11 Considering that it’s typically Rem’s strength, the dearth of this kind of approach—reveling in the gray area, building arguments with affect as much as with information—is Countryside’s actual surprise, not its thesis.

Though Koolhaas extolled Wright’s ramps as a “wonderful tool to present a narrative,” he does not leverage this perfect opportunity to draw viewers into the complexity, winding slowly upward, step by step.12 Instead the only narrative to assert itself as visitors plod onward is one of accumulating expertise and cultural capital. In his contribution to the exhibition’s accompanying book, Therrien explains Koolhaas’s history of productive detachment and its relationship to the show’s reportage as follows: “A journalist before going to architecture school, RK told me when we began working together that his mentor had taught him to ‘approach every situation like a Martian, completely foreign and amazed, and write it all down deadpan.’ The countryside has long—always?—been chock-full of experts, overflowing with opinions, flooded by interpretations. But Martian strategy is necessarily unimpressed. Even the duly-picked-over can be a rich harvest. Calling it ignored is not ignorant, it’s strategic.”13

But this curator’s wishful thinking aside, the glossing over of so much existing, in-depth work on the picked-over subjects at hand in favor of creating a swirling veneer of seemingly urgent pluralism tends more toward appropriation than it does opening. A rich harvest indeed.

Alienated Expertise

As has been widely reported in the aftermath of the UN report—even by the UN themselves—allowing individual nations to define “urban” on their own, rather than using a shared metric, rendered that 2008 declaration’s force more intuitive than scientific.14 (An urban area in Iceland could have two hundred people, whereas in Benin it required ten thousand.)15 Nonetheless, it fed into and reinforced the narrative undergirding a deluge of research on urbanization during that period, of which Koolhaas formed a central part. It is that deluge against which he and his team are now reacting. Having long played fast and loose with the fluid taxonomies of “the city,” it is no wonder they have embraced its opposite with equal slipperiness.16 “Countryside,” a rather quaint and bucolic non-urban formulation, is also an imprecise term—due largely to its predication on the worn-out urban/rural binary. Emerging from the past years’ discursive cacophony, if there’s anything that all of the books and conferences tended to reveal, it’s that there really is no such thing anymore as “outside the city.” Between smartphones, supply chains, and world banks, the countryside doesn’t exist.

This is, of course, not to flatten the planet’s occupied and unoccupied spaces into a single descriptive field, nor to insinuate that experiences on palm oil plantations in Indonesia are somehow equatable to those in micro-housing units in London. On the contrary. In some sense the visual clutter is a commendable testament to the challenge of earnestly describing the indescribable. But if one scratches at any of its many surfaces, Martian strategy’s facts-not-feelings approach ultimately belies its opposite—a distinctly slanted fiction, which critical reception of the exhibition prior to its pandemic-related closure was beginning to reflect.17

That this affective strategy—an aesthetic “beyond the aesthetics”—might finally be wearing out its effectiveness would be a welcome development in architecture culture.18 Because in this field that stretches from starchitects to technocrats, obsequious (if stylized) adherence to outdated notions of apolitical expertise has long run its course. Because Koolhaas, like all other humans, doesn’t come from Mars. He comes from northern Europe.

More specifically, his regular vacations in the Swiss Alps seem to have played a foundational role in the Countryside project’s genesis and subsequent framing. Upon noticing a growing number of unfamiliar forms and faces in the evergreen village he frequented, Koolhaas was compelled to investigate. And it was allegedly that initial disturbance in the nostalgia-sphere that led to the exhibition’s panoply of local and global demonstrations (not coincidentally emphasizing East–West comparisons at the expense of those reaching from south to north) that the countryside was “no longer innocent.”19

The Euro-masculine curatorial team’s stated indifference to political correctness—a claim undercut by stochastic emphases on eco-feminism and University of Nairobi–guided student projects—is meant to bolster the alien, just-the-facts approach.20 Unaccounted-for first person permeates the show, as does persistent deployment of the concept of various cultural and technological “frontiers” and their explorers’ manifest curatorial destiny.21 (Such avowedly detached accumulation and deployment of globe-trotting expertise—especially when considered alongside the flippantly playful authoritarian robots roaming the ramps—brings to mind a former employee of Koolhaas, Bjarke Ingels, whose recent “Yes Is More” dalliances with the fascist regime in Brazil have gotten him in quite a bit of warming water.22) And pre-butting the predictable criticism of this approach does not relieve critics of their responsibility.23

Under the stated surface, however, and more proximate to Koolhaas’s home villages, an alternative geotechnical genesis story for the project is offered by Therrien in his catalog text—one that more directly relates the show’s ambiguously yet determinately non-urban content to the continua at the core of its contemporary relevance. Living in Amsterdam and working in Rotterdam requires an hour-plus commute for Koolhaas. And it was through the window of his BMW on this commute that he first encountered the industrial agriculture that would become so central to his forthcoming decade of research.24 But instead of looking out onto the passing landscape, Koolhaas might have done well to train his focus on the much closer and more comfortably familiar space inside the window’s tint.25

Running on Empty

As a connective technology so central to the story of urban-rural flux and its associated built forms, cars occupy a surprisingly small part of Countryside’s real estate. Car ownership rates continue to rise around the world, along with carbon emissions and urban sprawl, in direct correlation with the ex/sub/rurban spaces being both emptied and occupied.26

The spectral presence of the automobile is lent extra force by the architecture of the Guggenheim itself, whose own formal genesis happens to be yoked to it. Originally envisioned upside down as an “automobile objective” for Sugarloaf Mountain outside of Baltimore, Maryland, the 1920s ziggurat that prefigured the museum was likened to the Tower of Babel by the client, businessman Gordon Strong, and to a snail’s shell by Wright.27 But for both Wright and Strong, between whom disagreement was near-constant, the mystique of the personal automobile was always central to the project. Following World War One and prior to the onset of the Great Depression, suburbia was beginning to blossom and with it so were mediatized visions of family-oriented leisure located farther from work and closer to nature.

In one of their many arguments, while defending the “organic integrity” of the ramps’ placement on the exterior rather than interior of the monument, Wright insisted to Strong that the day-tripping visitors’ views from Sugarloaf must be from the windows of their cars—where they “both now really live and have their beings”—“in a novel circumstance with the whole landscape revolving about them, as exposed to view as though they were in an aeroplane.”28 In other words, the Guggenheim ramps’ original purpose was to facilitate an encounter with and understanding of the countryside from the safety, security, and remove of a half-day trip away, but never gone, from the city.29

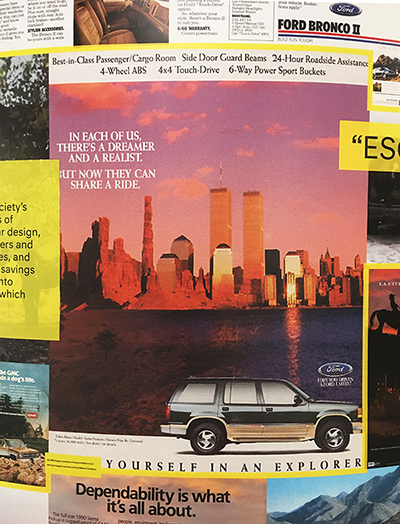

The exhibition’s “semiotic column”—visibly transecting all levels of the rotunda and covered in advertising and other commercial products gathered largely by students at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design under the guidance of Niklas Maak—is one of the only surfaces in the museum where automobiles make a concentrated appearance. As is the case elsewhere, much is made in these advertisements of the drive to escape, to adventure, or to leisure, all of which can apparently only be fulfilled by the countryside.

The fulfillment of such desires isn’t unrelated to the data packets moving from the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center to personal computers, the Amazon boxes on conveyer belts in suburban New York, or the Belt and Road Initiative’s dispensation of debt in central Kenya. But visitors needn’t turn their gaze away from the city in order to apprehend these machinations of fulfillment, as Koolhaas and his collaborators here suggest. Or, in the words of a Ford Explorer ad featuring a collage of New York City’s Twin Towers and rugged red canyon cliffs: “In each of us there’s a dreamer and a realist. But now they can share a ride.”

City Beautiful

In the years since the UN declaration, the city has increasingly been found in the country, and vice versa. More than the show’s “global villages” in southern Italy, included for their sensitive, revitalizing incorporation of Middle Eastern and African refugees, its foundational binary would have done well to more prominently embrace another kind of “global village”—an uneven but planetary-wide network where established geographical and cultural boundaries are blurred at the same time that new financial and political firewalls are encoded.30

After all, the millions of people who’ve moved from the country to the city in recent years haven’t abandoned their life experiences along the way. The evolving crises of COVID-19 have as much to do with airports as they do with wet markets. “Yellow Vest” organizers in exurban Paris and “Liberate Michigan” protesters in Lansing perform their reliance on car culture both to resist the neoliberal city’s patronizing hegemony and to claim their rightful share of its fruits. “Inner-city” fast food workers in the Bronx have much more in common with undocumented poultry plant employees in Iowa than they do with Wall Street managers. And as Koolhaas has already shown, Fashion Week in Milan isn’t as far from Nevada as he might otherwise have Guggenheim visitors think.31

OMA/AMO’s evident attraction to the “beauty” of the non-architect-designed, “cartesian” industrial architecture of the countryside would have made for an interesting video in the spirit of Niermann’s love letter to the ocean. More vivid, self-aware explorations of contemporary spaces of connection—such as the car—that defy easy categorization would have both informed and excited, meeting visitors (or now, listeners32) where they actually are. Embracing as it does the charge of propagandizing the countryside for patrons of this venerable Fifth Avenue institution, the exhibition does a disservice to the imaginative power and investment of those who already live there, who have lived there, or who might live there in the future—which is to say, everyone.33

Koolhaas wrote Delirious New York, his “retroactive manifesto” on the city in 1978, around the same time that oil executives began studying, and hiding, the creeping reality of climate change. This persistent, engineered obfuscation is, in part, what the show is meant to assist in undoing. But with the abandonment of avant-garde art and architecture, the more typical domains of the museum, in favor of rearguard (retroactive?) research and reporting, Countryside isn’t likely to penetrate the imaginaries of power of which it speaks. The challenge of more frontal engagement with such pressing concerns is even acknowledged by the curatorial team themselves, who worry aloud in the text affixed to the underside of the rising ramps: “How relevant can our insights and opinions be if they barely enter the arena where the confrontation takes place?”34

They know that arena is the city; they’ve been there all along. Instead of embracing its difficult ambiguities in order to support the coherent development of progressive cultural articulations, the exhibition has simply offered an architectural public weary of self-serving navel-gazing more of the same—a bait and switch when we can least afford it.

Underneath the pavement, the beach.

Underneath the beach, the pavement.35

-

John Prine, “Living in the Future,” Storm Windows, 1980. John Prine died on April 7, 2020, due to complications resulting from COVID-19. See link. ↩

-

Adam Gabbatt, “Protests against US stay-at-home orders gain support from rightwing figures,” April 16, 2020, the Guardian, link. See also Delilah Friedler, “Activists Are Still Taking to the Streets—in Cars,” April 3, 2020, Mother Jones, link, and Kea Wilson, “CAR ‘SIT-INS’? Drivers Are Drowning Out the Voices of the Most Vulnerable During COVID-19,” Streetsblog USA, link. ↩

-

Some protests have remained more physically distanced than others. See Lois Beckett, “Armed protesters demonstrate against Covid-19 lockdown at Michigan capitol,” April 30, 2020, the Guardian, link. ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal, vinyl text adhered to underside of ramps, Guggenheim Museum. ↩

-

“See Countryside, the Future at the Guggenheim,” Guggenheim Museum, link. ↩

-

Remarks by Rem Koolhaas in media preview, February 19, 2020. ↩

-

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), “World Urbanization Prospects, 2007 Revision,” link. ↩

-

Remarks by Rem Koolhaas in media preview, February 19, 2020. ↩

-

Sean Joyner, “AMO and Volkswagen team up to develop electric tractor,” March 6, 2020, Archinect, link. ↩

-

Remarks by Rem Koolhaas in media preview, February 19, 2020. See also Troy Conrad Therrien in “Welcome from the Guggenheim Curators,” Audio Guide, Guggenheim Museum, link. ↩

-

Troy Conrad Therrien, “Along for the Ride,” Countryside? A Report (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2020) 14. ↩

-

Hung Vo, “Revisiting the ‘Urban Age’ Declaration,” Global Sustainable Development Report, link. ↩

-

Vo, “Revisiting the ‘Urban Age’ Declaration.” For more on this slippage’s contemporary ramifications, see Amal Ahmed, “The Next Census Could Determine the Future of Port Arthur,” April 17, 2020, Texas Observer, link. “This puts a place like Port Arthur at a disadvantage. If a city’s population drops below 50,000, it’s no longer considered an urban area. This different designation means it could lose some of the federal dollars directed toward larger metropolitan areas, including school funding and transportation projects. Port Arthur is on the precipice; in 2010, the city had just over 53,000 residents.” ↩

-

“If the Chinese call it a village, who are we to question that?” Remarks by Rem Koolhaas in media preview, February 19, 2020. ↩

-

See Ian Volner, “Devil’s Haircut,” March 4, 2020, n+1, link; Justin Davidson, “Farm Livin’ Is the Life for Me, Ja? Rem Koolhaas Tries Out Country Life,” February 24, 2020, New York Magazine, link; Inga Saffron, February 20, 2020, Twitter, link. ↩

-

Troy Conrad Therrien, “Along for the Ride,” Countryside? A Report (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2020), 13. ↩

-

Remarks by Rem Koolhaas in media preview, February 19, 2020. ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas interviewed by Oliver Wainwright, “‘The countryside is where the radical changes are’: Rem Koolhaas goes rural,” the Guardian, February 11, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Eschewing nostalgia for the unknown and upcoming is the dynamo that propels this project. RK is not retreating to the wilderness in his twilight; he, AMO, and their collaborators are pressing on to yet another frontier.” Therrien, “Along for the Ride,” 13. ↩

-

Tom Ravenscroft, “Criticism of Jair Bolsonaro meeting is ‘an oversimplification of a complex world’ says Bjarke Ingels,” January 23, 2020, Dezeen, link. ↩

-

Therrien, “Along for the Ride.” See also Volner, “Devil’s Haircut.” ↩

-

The Westland region of the Netherlands is also known as the “Glass City” due to its dense collection of industrial-scale greenhouses. Therrien, “Along for the Ride,” 12–13. ↩

-

… along with his reflection in it. ↩

-

See Fig. 15 in “The Green New Deal: Assembled Annotations,” graphic produced by Partner & Partners, based on research done by the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, drawing from the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, link. ↩

-

Correspondence between Gordon Strong and Frank Lloyd Wright, October 14, 1925 (80322.2); October 20, 1925 (80323), The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art and Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). ↩

-

Correspondence between Gordon Strong and Frank Lloyd Wright, October 20, 1925 (80323.2), The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art and Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). ↩

-

After all, uptown Manhattan was rural once, too. Just across Fifth Avenue, the great urban oasis of Central Park was built on top of an expropriated settlement established by free black landowners. See Ujijji Davis, “The Bottom: The Emergency and Erasure of Black American Urban Landscapes,” Avery Review, October 2018, link. ↩

-

See also Marshal McLuhan on his own version of the “global village,” recently republished in The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011). ↩

-

See “‘Cartesian Space’ AMO for 2019 SS Prada Man’s Show,” July 1, 2018, Bigmat International Architecture Agenda, link. ↩

-

Countryside, The Future Audio Guide, Guggenheim Museum, link. ↩

-

Remarks on “propaganda” made by Rem Koolhaas in tour, February 17, 2020. ↩

-

Vinyl text adhered to underside of ramps, Guggenheim Museum. ↩

-

“Sous les pavés, la plage!” was a widely circulated slogan during the May 1968 protests in France. Michael Sorkin included the translated phrase as number 211 in his 2014 text “Two Hundred and Fifty Things an Architect Should Know.” Its inverse was number 212. Michael Sorkin, What Goes Up: The Rights and Wrongs to the City (New York: Verso, 2018), 283. Michael Sorkin died on March 26, 2020, due to complications from COVID-19. See link. ↩

Jacob R. Moore is a critic, curator, and editor based in New York. He has history, and family, in cities large and small in Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Louisiana.