I can’t tell you how many times I’ve already rewritten this letter, to and from a city for which I share a complicated affection. Each draft seems as rapidly dated as the last, in this place where the coronavirus has compressed time in the same way the city compresses distance, each a different version of myself with his back to the water, trying vainly to see what he can’t of the successively breaking waves to come.

The dimensions, space and time, have also begun to blur. Under the threat of this crisis, in a handful of rooms that keep feeling smaller, I’m confronting my presence here in a way wholly different from the usual packed pace of city life, which occasionally revs into the disorienting but always seems to find a strangely steady rhythm. New York “matches our energy level,” as Joan Didion once said with biting accuracy, and it also leaves us gasping for answers when it fails to live up to our imaginations’ carefully constructed and fragile orders.1 When our list of reasons for being here—“diversity,” living close to others, opportunity—end up the deciding factors of a tragedy with a still-climbing death toll of over seventeen thousand people (over five times the number of people who died in the World Trade Center on 9/11) in the course of two months.2

I know I’m not alone in thinking through the significance of this fallout, though it seems we have all arrived at differing conclusions of differing levels of confidence about what it means going forward. Editors across the country, for instance, seem to have agreed on the prevailing and to some degree merely revivified theme of “How do you predict the death of the city?” a genre of reportage morbidly fascinating in its range of unfounded assumptions about how city life works and its equally unqualified claims about what a return to idyllic city life will look like post-COVID (al fresco dining, that opiate of the masses, seems poised to play a major role).3

Questioning the future tense of our shrinking and threatened urban world inevitably leads to questioning our place in its present (what am I doing here; what can I do now?) and inevitably in the past, too (what brought me here?), collapsing them together in ways that make apparently solid former answers unravel. Looking at photos of the trip when I first fell in love with New York, a previously unremarkable image of myself spoke out. An eighteen-year-old me stares into the camera, his best friend on his right shoulder, thinking, I’m sure, about how he knows New York, about how he’ll soon be able to write the next great New York novel, while the people who make the city the city stand behind him looking in other possibly equally convicted directions, writing out, perhaps, their own definitive New Yorks while still somehow presenting this single cohesive picture. I look at it and think of how in the next year that goon who couldn’t even set the frame right will eventually read Jane Jacobs for the first time and discover why he loves to haunt the neighborhoods around Houston and West Fourth Street. How he’ll pine for the urban village that helped put a name to his romanticized notion—the people all knowing one another, the street ballet, the power of a richly heterogenous local community—and search for it everywhere he goes.

Compressed time. I doubt he could have predicted my current privileged position, getting to study as a resident the narrative history of a city he loved without question. Probably he would have reacted to it with envy. But letting those dreamy visions linger in the comforting realms of nostalgia no longer seems an option in a city pressed to redefine itself for future survival. I’m older now, or at least I feel much older looking at that picture. Today, I feel the need to confront those assumptions. For all this talk of the “urban village,” I’ve never actually seen it, and I doubt he ever did either.

Maybe I’m a skeptic, or a cynic, or just plain unfair. Really, I think I’m trying to be honest with myself as well as others. Because I could tell you about Miss Diggs on the first floor, a vegan who makes her own nut milks but indulges in animal products from the gourmet butcher when she has the inspiration, who keeps her plants in the windows during the day and who doesn’t regret moving uptown from Brooklyn. I could tell you about the former community organizer whose career mostly ended due to a traumatic brain injury and about how my roommate and I have been engaged with her in history’s quietest cold war between our morning jazz and her mysterious blunt instrument of choice. I could tell you about the four generations of a family who live in our building, about the woman who helped found the co-op by placing herself in a chair in the lobby and chasing out the addicts, about Mr. Smithson’s mother in Florida, our super’s street art side hustle, and the lifelong resident who waits outside for tourists to try to park their bikes against the fencing before chasing them away. (To my mother: “Oh you’re his mom. I see it now. You’re fine.”) But I would never claim myself a villager because I have no more delusions. The idea is deterministically reliant on proximity, and it wasn’t what life looked like in the city prior nor is it what it will look like in the city future. Still, we rely on the idea of the urban village because it’s much harder to ask ourselves what it means to be a good neighbor.4

Literary theorist Jacques Derrida predicates neighborliness on a paradox, what he terms “hostipality.” “If I welcome only what I welcome, what I am ready to welcome, and that I recognize in advance because I expect the coming of the hôte as invited,” he writes, “there is no hospitality.”5 Similarly, grown-sad-boy provocateur and philosopher Slavoj Zizek advances the concept of the neighbor as distorted by the ethical asymmetry of offering love/welcome to only some and not others, referring to those others as the implicit “third” or “exception” of the neighborly relationship: “I have to make a CHOICE to SELECT who my neighbor is from the mass of the Thirds, and this is the original sin-choice of love,” as he writes in his characteristically titled “Smashing the Neighbor’s Face.”6 Of relation, I much prefer Bill Nunn’s monologue as Radio Raheem on this same theme from Do the Right Thing (1989), though he never explicitly names the notion of the neighbor: “The story of life is this—static—one hand [love] is always fighting the other hand [hate].”

I don’t feel the need to overly psychoanalyze the power dynamics that mark my relationship to the people with whom I happen to share plumbing and a lobby (it’s a co-op, so the idea of neighbor by virtue of another’s selectivity certainly applies), but I do believe something in these arguments about the neighbor applies more broadly to the urban village. Namely, that the concept premises itself on exclusivity, a sort of righteous territorialism that the compression of our current moment has placed, for me, into sharp focus.

Calling any part of a city an “urban village”—our desire for some cohesive sense of place notwithstanding—is a bit like applying the term “jumbo shrimp” to tiny crustaceans, or “hidden gem” to a neighborhood people have occupied for the last fifty years off a major public transportation stop. In other words, I suppose you could use the phrase to describe certain places at certain moments in time for the sake of simplicity, but overall it does not hold up to historical scrutiny or function. From the earliest studies of modern city neighborhoods, scholars have drawn neat distinctions between the two descriptive terms that “urban village” comprises. “While in the modern city we still find people living in close proximity to each other, there is neither close co-operation nor intimate contact, acquaintanceship, and group consciousness accompanying this spatial nearness,” wrote the Chicago School sociologist Louis Wirth in the 1920s, stating a clear contrast between his observations of early Chicago neighborhoods and the communal life of small towns and villages.7 Cut to most any decade of the twentieth century and the same observation repeats itself: Communities constantly reshaped by movement and succession, held tenuously together by common ethnic or institutional ties no matter what major city you choose to look at, and which organize less out of positive centripetal forces than to defend themselves from invasion: from urban renewal, from machine politics switching them out of favor, but mostly from people who aren’t like them, from people who are typically poor, and most often, from people of color.8

That’s part of what makes the widespread conceptual uptake of the urban village since it got swallowed whole by 1960s and 1970s brownstoners, the first wave of gentrification as some call them, so galling—a particularly glaring maladaptation of Jane Jacobs’ carefully though incompletely laid-out theory of the city as complex, interactive organization of neighborhoods that range from the city as a complete unit to subdistricts to street-level “neighborhoods.” (Jacobs, in fact, acknowledged that referring to an urban neighborhood as “a village” was “both silly and destructive.”)9 Which is to say, to celebrate the village is to celebrate the tribe, and to celebrate the tribe is to celebrate what Jacobs calls “turf”: when a group, whether a street gang or a resident association of Stuyvesant Town, “appropriates as its territory certain streets or housing projects or parks” so that others “cannot enter this Turf without permission from the Turf-owning gang, or if they do so it is at peril of being beaten or run off.”10

Why we have allowed the urban village trope to endure reflects our inability to let go of the romance of cities as an archipelago of urban villages and serves as testament to our unwillingness to confront the city as a temporal vector, something made especially obvious as the coronavirus weighs down the horizon of the city’s future.11 Fights over whose village is whose papers over the present with a non-extant past to try to control the future, offering the promise of unequal neighborhoods frozen in place for the sake of some undefinable “community” or “character” rather than using them as anchors for redistributive purposes.12 Brownstoners found the idea convenient as a rallying point to defend their properties and retain a dubiously “authentic” landscape of preserved nineteenth-century houses worth more in nostalgia than in truth.13 Communities of color found it useful to articulate a new but ultimately limited form of neighborhood control.14 And lingering white ethnic communities squeezed on one side by the growth of black and brown populations in the city during the middle decades of the twentieth century and on the other by competition for housing from newly arrived white white-collar workers (a group who overwhelming chose not to move to black neighborhoods, an observation still largely true of “gentrifiers” today)15 found it an excuse to fight, sometimes violently, for the preservation of their racially restrictive “turf.”16

As the city hurtles onward and change accelerates, the urge to preserve one’s own “turf,” the time and place that feels most familiar, seems only natural. The problem is that there are approximately nine million indefinite ideas of what this moment is constantly moving through the city at any given time, occasionally if ever overlapping. As Colson Whitehead has written: “To put off the inevitable, we try to fix the city in place, remember it as it was, doing to the city what we would never allow to be done to ourselves.”17 In other words, by issuing sentimental judgments based on simple spatial observations offered irrespective of larger patterns played out over time (i.e., “this guy moved last week, therefore the neighborhood is changing” even though twenty people moved out a year ago and you didn’t notice until the second coffee shop opened), we try to suppress the deeply subjective nature of our fixations. We then repeat the judgments of others who, like us, want to make the city conform to some similarly dubious reflection.

This could go some way toward explaining how Sharon Zukin, like many others, has opined that “in the early years of the twenty-first century, New York City lost its soul” due to local residents being pushed out by short-term-living gentrifiers, though the data says entirely the opposite.18 The average median length of residence in a housing unit for all households across New York City’s five boroughs has, in fact, increased from 2000 to 2015, from a 43 percent increase of three years for residents’ tenure in Manhattan to a 63 percent increase of five years for residents’ tenure in Staten Island.19 Ironically, the “authenticity” Zukin saw to be disappearing, which she defines as the “the expectation that neighbors and buildings that are here today will be here tomorrow,” seems more intact in the first decades of the twenty-first century than it was at the end of the twentieth, though it also raises the question of which neighbors and which buildings.20 From 2000 to 2015, the median age of New York City housing units also increased across all boroughs, up nineteen years in the Bronx and Brooklyn (a 40.4 percent and 34.5 percent increase, respectively), twelve years (22.2 percent) in Manhattan, fourteen years (28 percent) in Queens, and twelve years (38.7 percent) in Staten Island.21 What we have in New York is an affordability crisis more than a crisis of “staying put,” where the increasing stability of residency casts light on decreasing socioeconomic mobility.22

To build a better city of the future, to reimagine neighborhoods and urban collectivity in a way that is more enduring and also more equitable, will require much more than a generous reconfiguration of a past that never was. It will require a radical rethinking of what binds a city’s many districts and subdistricts, a thorough examination of what gives New York its sense of togetherness and also its sense of intimate, distinct communities even as every part of it moves.

Incidental symmetry inside the New York City subway, 2004. Heads bowed into books or electronic devices, or looking out into directions no one can actually see, a togetherness-by-accident emerges within the interior space and radiates outward into the city. Take, for instance, the 1954 Roy DeCarava photo where two men stand evenly split the platform steps—titled, appropriately, Subway stairs, two men—taking no notice of each other or their compositional balance. In their incidental symmetry, they urge an unconscious dialogue between themselves, the environment, and the viewer.23 Here, I'd argue, is precisely where the city begins to speak.

Standing among the people of the subway decades prior, another photo renders the spontaneous dialogue become more intimate while anonymous. On a rush hour train amid a hundred gazes staring past one another, she looks right back into your roving vision.24 A raised brow, mouth partially open, she wonders why you chose her to linger and when you caught her looking. You both pause, then turn away.

These passing interactions, the contrast and fleetingness of these intimacies, remind one of what it means to be viewed as a functional part of the surroundings, the greater collective nurtured by this poetically maintained separation amid the closeness, what E. B. White called “the gift of privacy with the excitement of participation.”25 No matter what happens up top, the subway is New York at its most optimistic, its most sincere, and its strongest for all of its failures: as Ann Petry captured like none other in The Street (1946), “making room for themselves where no room had existed before.”26

The subway inverts the city’s order and rewrites (as legibly as possible) the urbanist hymn of contact. There Ellison observed in the five o’clock cars “underground arenas in which Northern social equality took the form of an endless shoving match,” a stepping out of the raced and classed and gendered social order so stark that it left even him, the great jokester, “shaken”—perhaps even helped him figure the poetics of being underground that would shape Invisible Man.27 Langston Hughes, similarly, saw a crowd so tightly compressed and so bound by sensation that words failed to express the singularity. Instead, he let it be felt between the lines of his poem “Subway Rush Hour” (1951):

Mingled

breath and smell

so close

mingled

black and white

so near

no room for fear.28

There are limits to these contacts, to be sure—epitomized by the quintessential ultra-rich caricature of Sherman McCoy screaming “Insulation!” at the sheer thought of ever riding on the subway, part of a demographic visibly abandoning the city once more in its dire hour29—and yet we thrive among them. The subway is a representative composite, the sum total, of all those who actually participate in the city’s vibrancy, of all the passing relationships that epitomize what we’ve chosen in choosing urban living. The supers who keep the trash from your hallway and your apartment from going up in smoke, the people who enter and exit the lobby with you at the same time on a consistent basis, the other regular at the bar or café, the bus driver who switches languages with you on the way to work every morning. Links designed to go no further than the present and to not be determinative of past or future.

What shocks me more than anything is the presence of a single, overwhelming order that brings us together at great scale—a village, a golden era of the city, whatever you like—and which, when pressured, destabilizes the already fragile notions that separate place and self. Illustrated by one Francie Nolan in the 1910s in Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the amazement and confusion of everyone on the elevated crossing to Manhattan over the Williamsburg Bridge simultaneously rising to stare in the same direction, measuring their lateness against the clock of the Williamsburg Savings Bank along with a million others.30 In that moment, without residing, cohabiting a space much larger than what they would normally be able to call their own. A place where—despite the impossibility of there being any single encompassing image of the city, as Kevin Lynch has it—they could nonetheless spot how their various visions were “more or less overlapped and interrelated.”31

Even while declaring “Here Is New York,” E. B. White maintained that every reader’s job is “to bring the city down to date,” to reach across time and stare into the same surfaces while figuring another meaning, to make room for ourselves alongside the others, yet unseen, as we prepare to also be jostled aside for the city to continue.32 What of that clock, no longer quite necessary for the sake of keeping time, now jeweling the occasional mention of local quaintness? I don’t believe that it ever did toll in a village, though the self-proclaimed artisans of Williamsburg may want to think so. Instead, I think it serves as an uneasy reminder of our own mortality—similar to the moment we find ourselves in—as we locate against its looming presence our own small eclipses of the hour, still and always uncomfortably ticking past us.

Do not panic. Take a long walk over the bridges. Stand halfway across the Triborough (RFK, whatever) and look out—for the best vantage point, I’d say, just about when you cross over Randall’s Island from Astoria. Pause midway on the Third Avenue span crossing the Harlem River and do a 360. There you get to be most at one with the city, because, as Samuel Delany wisely put it, New York City is always at a “midpoint,” each of its parts “in a process… undergone many times,” the city itself an endless and disparate parade of transformation.33

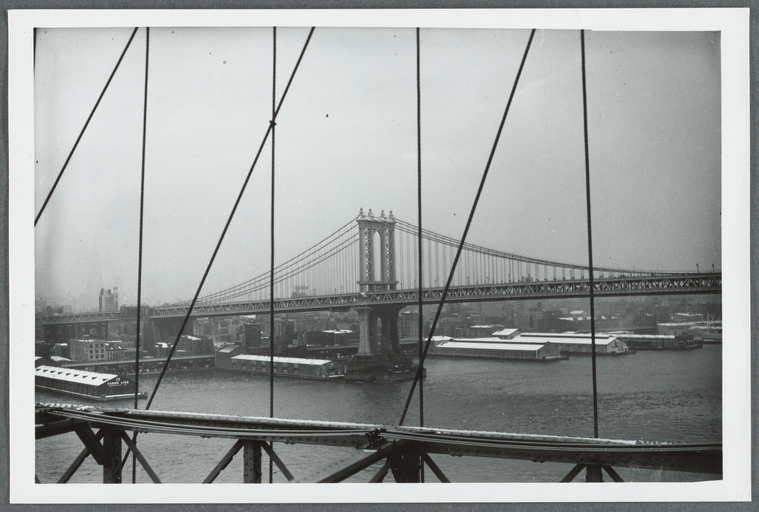

Bike to the midpoint of the Manhattan or the Williamsburg and pause for a moment at the apex before hurtling along with a century’s worth of maintenance and engineering—human hands and minds—behind you, to whatever lies on that other side. Feel the rattling of the cars and the trains (emptier though they may be) alongside you, the cracks in the concrete as they pass up the trusses and shocks to your legs, the alternating tickle of sunlight that strobes across your face as you pass through the buildings and beams’ shadows, the thunderous hush ringing in your ears of a city on pause.

I’d love to tell you what it will look like at level, or that it will be easy getting there. But I don’t pretend to have any answers about that future, other than that it will require a fight with something more meaningful and imaginative than banging pots and pans out the window if we want it to indeed be better when it comes. For now, I keep turning back to that compressing midpoint of a city always one step ahead and more lasting than us, and that I have been privileged to share with so many come and too many gone as of recent: It’s a caressing loneliness, even in its loneliness, the room that’s been made for you here.

-

Joan Didion, “Sentimental Journeys” (1990), collected in We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live (New York: Everyman’s Library, 2006): 727. ↩

-

The virus is disproportionately killing people of color across the nation, mostly due to the economic marginalization that leads them to take “essential” jobs that require continued interaction with people despite the pandemic’s lockdown. ↩

-

For a sample of “death of the city” reporting, there’s Michael Kimmelman, “Can City Life Survive the Coronavirus,” New York Times, March 17, 2020; and Uri Friedman, “I Have Seen the Future—And It’s Not the Life We Knew,” the Atlantic, May 1, 2020. On al fresco dining, see Tanay Warerkar, “NYC’s Restaurant Reopening Could Include Outdoor Seating on Closed Streets,” Eater NY, April 28, 2020. ↩

-

I have changed the names of my building’s residents for privacy purposes. ↩

-

Jacques Derrida, “Hostipality,” in Acts of Religion, ed. Gil Anidjar (New York: Routledge, 2002), 362. ↩

-

Slavoj Zizek, “Smashing the Neighbor’s Face,” on Lacan.com, link. ↩

-

Louis Wirth, “A Bibliography of the Urban Community,” in The City by Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, and Roderick D. McKenzie, with a bibliography by Louis Wirth (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 190. Collection first published 1925. ↩

-

See the chapter “A Strange Sense of Community” in Carlo Rotella’s The World Is Always Coming to an End: Pulling Together and Apart in a Chicago Neighborhood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 27–60. ↩

-

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Modern Library, 2011), 153. ↩

-

Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 60–64. ↩

-

On neighborhoods and cities as “temporal vectors,” see Andrew M. Fearnley, “From Prophecy to Preservation: Harlem as Temporal Vector,” in Race Capital?: Harlem as Setting and Symbol, edited by Andrew M. Fearnley and Daniel Matlin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 27-46. ↩

-

On the prevalence and persistence of neighborhood-level inequality, see Patrick Sharkey’s Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013) and Robert J. Sampson’s Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012). ↩

-

Sulemain Osman, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↩

-

Osman, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn. See also the discussions of community control in the context of the community school and community development movements of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Jerald Podair, The Strike that Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill–Brownsville Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); and Michael Woodsworth, Battle for Bed-Stuy: The Long War on Poverty in New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). ↩

-

Jackelyn Hwang and Robert J. Sampson, “Divergent Pathways of Gentrification: Racial Inequality and the Social Order of Renewal in Chicago Neighborhoods,” American Sociological Review 79, no. 7 (2014); Lance Freeman and Tiancheng Cai, “White Entry into Black Neighborhoods: Advent of a New Era?” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 660 (2010). ↩

-

Jeannine Bell, Hate Thy Neighbor: Move-In Violence and the Persistence of Segregation in Neighborhood Housing (New York: NYU Press, 2013), 56. According to Bell, the phenomenon of white working-class and ethnic groups violently reacting with this territorial defensiveness helped ensure that by the mid-1980s attacks on minority families moving to white neighborhoods would become “the most common form of violent racism in the country.” ↩

-

Colson Whitehead, The Colossus of New York (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 9–10. ↩

-

Sharon Zukin, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 1. This refrain is echoed in essays and books like Loretta Lees, “Super-Gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City,” Urban Studies, vol. 40, no. 12 (2003); and Peter Moskowitz, How to Kill a City (New York City: Bold Type Books, 2017). ↩

-

American Community Survey Data, 2000–2015 (Washington, D.C.: Published by the U.S. Census Bureau). Extrapolating the data to 1990 and beyond proves difficult since the year an individual moved into a housing unit is presented in year ranges, but at the very least by 2015 median New York City tenures were definitively longer than in 1990, a year in which all five counties had a median tenure of somewhere between six and ten years. See United States Census Bureau, “1990 Census of Housing: Detailed Housing Characteristics, New York,” Section 1 of 2, published by the US Department of Commerce (Washington, DC: 1990): link. ↩

-

Zukin, Naked City, 5–6. ↩

-

American Community Survey Data, 2000–2015. Like with median housing tenure, extrapolating the data to 1990 and beyond proves difficult since the years housing units were built are counted in year ranges, but at the very least, every borough other than Staten Island had an older housing stock by 2000 than it did in 1990. The median age of housing was between 31 and 40 years in the Bronx and Staten Island, and between 41 and 50 years in all other boroughs. See United States Census Bureau, “1990 Census of Housing: Detailed Housing Characteristics, New York.” ↩

-

Displacement, even in scholarly studies that most strongly indicate its presence, still does not register as the primary reason people may feel pushed out of New York. Kathe Newman and Elvin K. Wyly, “The Right to Stay Put, Revisited: Gentrification and Resistance to Displacement in New York City,” Urban Studies, vol. 43, no. 1 (2006): 23–57; Lance Freeman, A Haven and a Hell: The Ghetto in Black America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). ↩

-

Roy DeCarava, Subway stairs, two men (1954) in The Sound I Saw (London: Phaidon, 2001). As DeCarava writes in the margins of the collection’s many other subway photos: “... puzzled in the crush of every morning mash / when time presses and life is a tailor / who cuts to measure and makes the action / alike and different from each other alone / and endlessly apart with billions of different / brothers separated together all over everywhere / including not here where freedom’s talk is a fig leaf / counted to save all of democracy’s faces not black / where humanity searches for its soul is the hope / light hands in the trains will be hands / dark faces on buses just faces / to be lit on some subway platform with a / light from the beat of a heart / coming through a faceless tuba at newport...” ↩

-

Stanley Kubrick, “Life and Love on the New York City Subway [Man Carrying Flowers on a Crowded Subway],” on display in Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs at the Museum of the City of New York, May–October 2018, item number X2011.4.11107.115C: link. ↩

-

E. B. White, Here Is New York (New York: Little Bookroom, 1999), 23. ↩

-

Ann Petry, The Street (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1974), 33. ↩

-

Ralph Ellison, “An Extravagance of Laughter,” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison (New York: Modern Library, 1995), 617. On how Ellison’s early documentation of New York and especially its underground spaces would eventually factor into his novel Invisible Man (1952), see J. C. Cloutier’s chapters on Ellison in Shadow Archives: The Lifecycles of African American Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). ↩

-

Langston Hughes, “Subway Rush Hour,” in The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, volume 3, edited by Arnold Rampersad (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001), 71. ↩

-

Tom Wolfe, Bonfire of the Vanities (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1987), 55; Adam Gopnik and Philip Montgomery (photographer), “The Coronavirus Reveals New York at Its Best and Its Worst,” The New Yorker, March 23, 2020. ↩

-

Betty Smith, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (New York: Harper Perennial, 1992), 368. ↩

-

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Boston: MIT Press, 1960), 3–6. ↩

-

White, Here Is New York, 17. ↩

-

Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 14. ↩

Bo McMillan is a doctoral student of English literature working on an interdisciplinary dissertation about narratives and neighborhood change. His writing on urban history and culture has appeared or is forthcoming in American Literature, Public Books, the Chicago Review, City, this journal, and other various outlets.