How or why do we know something is infrastructural? Systems conventionally thought of as infrastructural including public transportation, communications networks, water, sewage, and electricity course through grids and networks that circulate services vital to the functioning of an economy. The mall, on the other hand, as a contained and isolated form that seemingly rejects the city itself, is difficult for us to imagine as an infrastructure. Borrowing from Cornelia Vismann’s definition of cultural techniques, Reinhold Martin asks us to think of infrastructure less as a thing-in-itself, and more as a characteristic of things, a shift in framing that allows us to evaluate the infrastructural qualities of any given object.1 Objects can thus be seen outside of their bounded isolation, and rather as a multi-scalar series of spatial, social, and technical relationships. This definition is particularly useful as a lens to evaluate the Philippine supermall.

The Philippines is home to some of the world’s largest shopping malls—it boasts five with gross leasable areas in excess of four million square feet. Each of these shopping malls is significantly larger than the US’s gargantuan Mall of America, which has a comparatively modest leasable area of 2.7 million square feet. In the Philippines, malls are not only large; they are ubiquitous, and it is difficult to underestimate the influence they have on daily life there. This is perhaps surprising given that the Philippines, by various metrics, is one of the poorest countries in Asia, with 21 percent of its population living below the poverty line and over 10 percent of its citizens working abroad at any one time.2 The prevalence of poverty and the prominence of the mall, however, is only ostensibly a paradox. In fact, they are conditions that depend on each other.

The Philippine supermall is far more than a retail infrastructure; it is the infrastructural core not only of Manila, but of Philippine urban space and even Philippine urban society. In a Philippine mall, you are likely to find, in addition to restaurants and retail stores, small amusement parks, ice skating rinks, government bureaus, utilities offices, daycare centers, medical and dental offices, and churches. And while most malls are not connected via rapid transit systems, most light rail stations in Manila (currently the only rapid transit system in Manila) are located within or adjacent to malls. Indeed, Philippine malls are so large, so numerous, and so popular that they are now fully accepted as the foci of many, if not most, infrastructural and urban development strategies.

In Manila, the malls that host mass rapid transit stations are the largest and most successful, which is why the construction of a light rail station on the fuzzy border between Quezon City and Manila was at the center of a decade-long legal row between the Philippines’ two largest mall developers. The dispute, between the Ayala Land Corporation and SM Prime Holdings, centered around the rights to build, operate, and locate the station in question adjacent to their respective malls—SM Prime Holding’s SM City North EDSA (the archipelago’s largest mall named after the highway along which the mall is built, the Epifanio de los Santos Avenue), and Ayala Land’s slightly more upscale Trinoma Mall (short for Triangle North of Manila). While the malls are located less than 100 meters from each other and are connected by a short pedestrian footbridge, each mall developer fought desperately to capture the station’s direct foot traffic.

The original intention behind the station was to link two major transit lines—the Metro Rail Transit Lines 3 (MRT-3) and the Light Rail Transit Line 1 (LRT-1). However, over the course of the decade-long debacle, development accelerated around the project site, and the ambit of the project expanded accordingly. While initially projected to accommodate 500,000 passengers per day, by the time an agreement was reached, the station was projected to serve 1.2 million passengers per day, an increase largely due to the fact that the station would now serve as the center point of Manila’s brand-new Metro Manila Subway (Manila’s first intercity underground subway system).3 In a complex solution aimed at appeasing Manila’s two most powerful oligarchies (and in the interest of maintaining the government’s relationship to what it viewed as its most important private partners), the station was divided into three distinct areas, each operated and financed by separate public and private entities.4 Recently dubbed the “Unified Grand Central Station,” the project is now slated for completion in 2022.

The evolution of the Unified Grand Central Station is only the most obvious example of how, in the absence of effective state or municipally driven urban planning strategies, transportation systems have followed the lead of private development. The relationship between malls and transportation infrastructure began rather casually with buses and jeepney stations clustering around Manila’s malls. This pattern was formalized with the placement of light rail stations either within or adjacent to malls and, as evidenced by the complex resolution outlined above, was followed by a holy alliance between competitive private developers and Manila’s transportation bureaus. This essay, however, is not about the relationship between the mall and transportation infrastructure but rather how and why the Philippine mall itself has become the basic organizational structure of Philippine urban space. Exactly what accounts for the popularity, outsize influence, and massive footprint of Philippine malls?

Strength in Numbers

In 1936, twelve-year-old Sy Zhicheng immigrated to the Philippines from Xiamen in the Southeastern Chinese province of Fujian to join his father in running two modest sari-sari stores in Manila. Both stores were destroyed in the Battle of Manila at the close of World War II. With no resources to rebuild, Sy’s father left his nineteen-year-old son behind. Surrounded by American soldiers in postwar Manila, Sy Zhicheng adopted the first name Henry. Taking advantage of the postwar economy, Sy made his first fortune by selling highly coveted American shoes imported by enterprising soldiers deployed in the Philippines to Manileños eager to buy anything American. In 1948, three years later, he opened his first shoe store in an area of Manila known as Quiapo. In 1958, in the same densely populated neighborhood, Sy opened Shoe Mart (SM), the first air-conditioned freestanding shoe store in the Philippines—taking advantage of the traffic that gathered around the busy Quiapo Church.5 By 1980 Sy had opened six department stores in Manila, all wildly popular with the Philippine masses who bought affordable and locally produced imitations of American shoe styles within a still rare and refreshing climate-controlled interior.

While Sy made a modest fortune from his small empire of shoe stores, it was not until the mid-1980s that Sy would find the opportunities that eventually made him the richest man in the Philippines. In 1985, only months before the People Power Revolution—or EDSA Revolution—that would depose President Ferdinand Marcos, Sy opened his first mall—a “supermall”—SM City North EDSA, with over a million square feet of leasable space. While foreign investors saw the Philippine political crisis as inevitably attended by an economic one, Sy, who made his first fortune amid the dismal destruction of World War II, glimpsed in the upheaval a unique opportunity. In the political instability of regime change and the subsequent wave of international divestment, Sy saw not economic disaster but instead “very, very cheap” real estate.6 When foreign investors bailed, Sy doubled down. What was unique about Sy’s approach was that from the outset he profited off of the underdevelopment of the domestic economy.

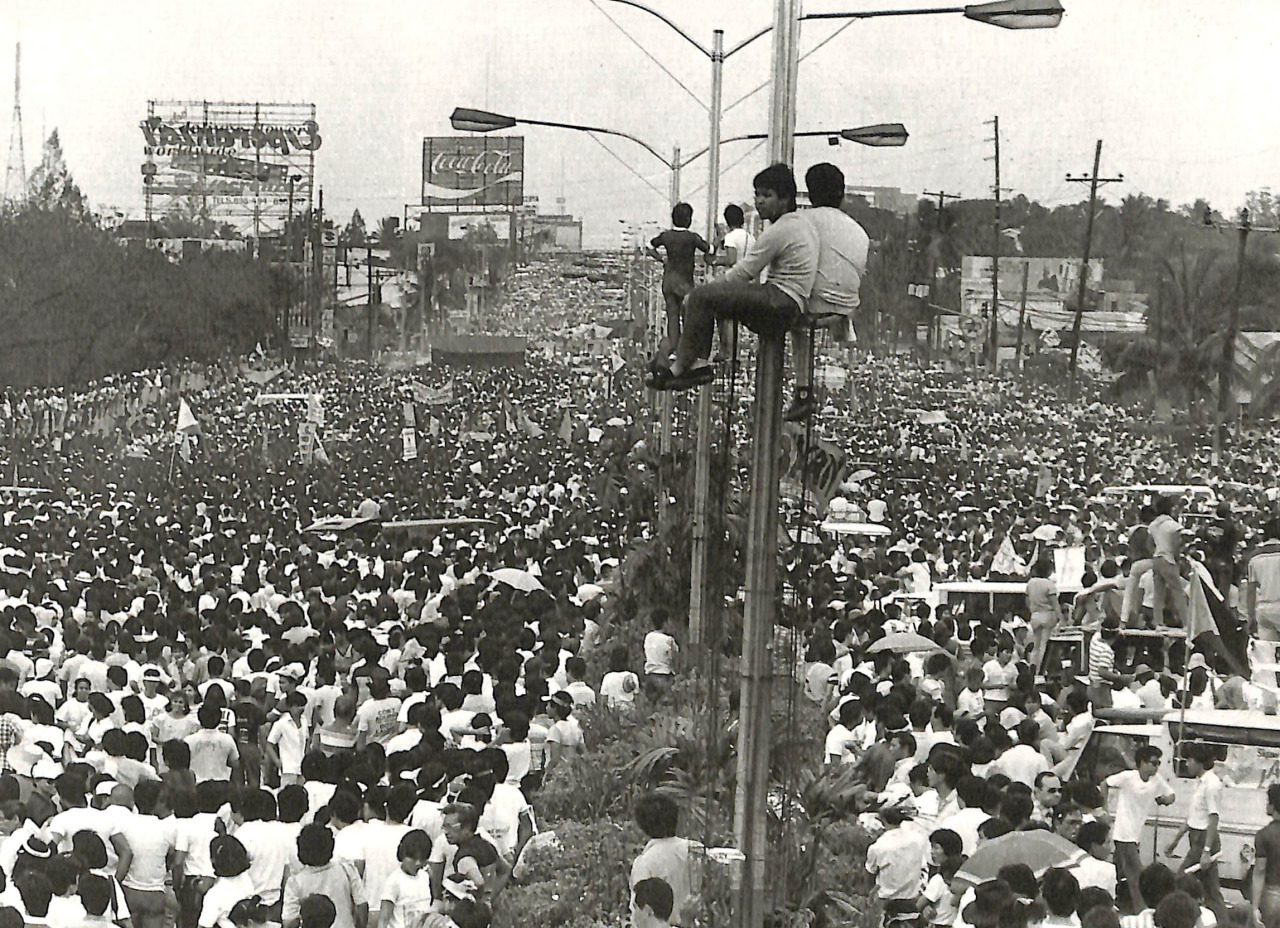

It was not only economic volatility that Sy took advantage of. Sy found opportunity in the appearance of the spectacular Philippine masa (masses) that occupied the EDSA during the People Power Revolution. In the masa, Sy did not see—as foreign investors did—a Socialist uprising. Instead he saw hordes of customers. Just as the Philippine masses first viewed the appearance of their own bodies en masse as a spectacle of power, so did Sy realize the potential profits they could generate en masse. It is no small irony that supermalls Trinoma and North EDSA are built along the very same highway after which the People Power Revolution is named. It was the very image of revolution occupying an eight-lane highway that would be the driving force behind Sy’s fortune. It is not difficult to imagine what Sy himself envisioned—a huge entrance to a mall at the terminus of a political march.

Sy named his business strategy the “strength in numbers” model. As its name suggests, the model relies on the size and purchasing power of the Philippine masa. In order to turn a profit, Sy banked on large masses of people spending very small amounts. His malls are thus necessarily huge, as they attempt to accommodate not the individual shopper but the masa. His forty-two malls, mostly located in Metro Manila, though scattered across the entire archipelago, are patronized by three million people every day. He furnished these massive interiors with countless cheap thrills including cinema multiplexes (the malls’ greatest single source of revenue), bowling lanes, billiards halls, ice skating rinks, and small carnivals with mini trains and micro merry-go-rounds. Much of what is offered is affordable for the vast majority of Filipinos.7

Alongside these small margins of profit, Sy also built his wealth on what he characterized as a vast “underground” economy, one almost totally dependent upon remittance wages earned in the extensive informal labor market of Filipinos working overseas. While the remittance wealth flowing into the Philippines remained unaccounted for (and untaxed) by official economic indexes, in 1994 Sy hypothesized that the Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW) was a “very big” class of consumer and estimated that as much as 30 percent of his sales came from this sector. He understood, above all else, that not all fortunes are built in the same way. Some fortunes, like his own, could be built upon globalization’s margins.8 In 2019, official remittances totaled US $33.5 billion—roughly 10 percent of the Philippine GDP, fueling a domestic economy based overwhelmingly on private consumption—a market that Sy claims a disproportionate share of.9

Recognizing the power of the masa was not Sy’s only strategy. He also took sizable control of the various aspects of his malls’ production, developing and financing a diversified group of long-term suppliers through a family-controlled savings bank, and buying 50 percent equity in one of the Philippines’ largest cement plants to simultaneously cash in on the cost of constructing his own malls while keeping those costs low. It was also the sheer size of the malls and the development of their internal infrastructure that allowed Sy to develop despite the city’s own lack of infrastructure. In 2014 during a nationwide power shortage that required rotating blackouts, the current CEO of Sy’s development company SM Prime Holdings, and Sy’s eldest daughter, Teresita Sy-Coson, reassured shoppers by pointing out that every SM mall was equipped with powerful generator sets in anticipation of such an emergency.10 The malls have grown so large and so numerous that they have begun to structure the city itself. Thus, the light rail and transit projects that are now routinely planned around malls are simply publicly subsidized extensions of a networked conurbation of privately owned supermalls.

While the money flows into Sy’s malls from every corner of the globe, it is the conditions on the ground, and the desires of the masa that remain at the center of SM’s business strategies. Sy-Coson until recently kept a no-frills office in Quiapo, the same working-class area where Sy established his first shoe stores. “It is here,” Teresita claims, “where I can determine what the mass market wants, what prices are really prevailing.”11 Teresita’s motivation to capture the desire of the “masses” demonstrates how a system of late capitalism heavily relies on forms of inclusion. This inclusion however, also relies on forms of exclusion. The OFWs, whose remittances Sy’s business model depends upon, experience two forms of exclusion—the first is from the societies in which they live and work, and the second is from the domestic lives they leave behind.12 When OFWs return to their homes, they often find it difficult to reenter the rhythms of the everyday life they left behind. The carnival-like atmosphere of Sy’s malls offers a distraction from the emotional distance that often develops after long stretches of physical distance.13 Remittances, when family members are away, enable a sort of disembodied practice of social participation. In other words, spending the money of someone both loved and absent is a form of communion for millions of separated Filipino families. The Philippine mall thus constitutes a form of domesticated space for the diasporic Filipino family—it is a space of intimacy and social connection—however compromised or attenuated. That is to say the Philippine mall has become an infrastructure of the Filipino diaspora, serving and drawing profits from a population that is always in transit, from those who spend their lives tethered between the increasingly blurred “here” and “elsewhere,” an opposition borrowed from anthropologist Marc Augé.14

The domestication of the Philippine mall by OFWs complicates (but does not oppose) the inclusion of the mall as a kind of paradigmatic non-place. Filipinos malls, wherever they are, feel not only familiar but even a bit like “home.” That is not to say that malls are places where OFWs feel completely at ease. Rather, the mall offers OFWs only a relative sense of ease akin to being at “home,” an indication of the alienation they feel both working abroad and back in their place of origin. At both sites, OFWs engage in consumerist practices as a means of ameliorating the social effects of distance. In the Philippines, malls are also the site where the Philippine government and NGOs engage directly with reintegration efforts by, for example, offering free mental health services during the Christmas season in December—officially “Overseas Filipino Month.” State-sponsored strategies such as the declaration of an official month dedicated to OFWs demonstrate how the OFW has become structural to the Philippine economy. That is to say, it is not just the lack of opportunities that drive Filipinos to work abroad; rather, the Philippines has developed a “culture of migration,” one that has fully naturalized the OFWs cycles of departure and return.15

Indeed, the OFW is hailed in both official and nonofficial ways as the “hero” of the Philippine economy. The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) stated in 2012 that the Philippine economy depended on cash remittances. The World Bank also listed remittances as a “key factor” for the resilience of the Philippine Economy.16 Numerous policies and the creation of government agencies support this economic activity by focusing on labor protection and welfare promotion of migrant workers both at home and in their host countries. This includes a vast number of loosely related organizations ranging from state-run institutions like the Philippine Overseas Employment Association, which regulates the operations of recruitment agencies and advocates for the rights of migrant workers, to NGOs like the Women in Development Foundation (WIDF), which is authorized by the state to run Pre-Departure Orientation Seminars, to blogs like dubaiofw.com, which collects job listings, migration laws, OFW interviews, and restaurant and leisure recommendations. While all of these organizations provide evidence of both the official and informal structures that support this now deeply entrenched migration culture, most of these organizations are merely coping mechanisms. The mall, however, is now so deeply intertwined with the Philippine society and economy that the former would be dysfunctional without it, while the latter might fail in its absence—a sure sign that the mall has become infrastructural.

The Non-Place Like Home

The Philippine mall is a place with deep cultural significance to the OFW population. However, this analysis of Philippine malls as infrastructure would be incomplete without addressing how they have also become the spatial and cultural anchors for OFWs abroad. In the absence of frequent social interactions with people other than their employers, OFWs flock to malls as a temporary balm for homesickness. There they meet with other Filipino OFWs in a location that offers a semblance of recognizable space, if not a familiar sense of place. As a result, malls in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Dubai are increasingly catering to, and learning to earn a profit off of, their large Filipino populations, where Filipinos make up 3 percent, 10 percent, and 21 percent of each of these country’s populations, respectively.17 One of the ways mall developers cater to their Filipino populations is by courting Filipino businesses. Perhaps the most conspicuous of these is Jollibee, the Philippines’ most popular fast food chain. There are twelve Jollibees operating in Saudi Arabia, six in Qatar, and five in the UAE. Abroad, especially in the Middle East, where OFWs virtually never acquire citizenship, Jollibee is popular with Filipinos where they can buy a familiar meal without dipping into what they might send back as remittances.18 Jollibee makes little attempt to advertise to Saudis, Qataris, or Emiratis. Rather, it directly targets a fiercely loyal OFW market. As a recent ad announced, There’s “no need to wait for payday just to enjoy your favorite meals. Get a Jollisavers meal in all Jollibee UAE locations.”19 The advertisement collapses the realities of a divided and limited income with the appeal of a familiar brand.

One’s experience at a Vietnamese Jollibee, where most patrons are Vietnamese (in Vietnam the Philippine diaspora hovers around only five thousand people), will be very different from one’s experience at a Jollibee in the UAE, where the vast majority of Jollibee customers are Filipino. In the Dubai Mall (the second largest mall in the world by total area), the Jollibee is just one of a number of fast food options that collectively form the Food Court’s spectrum of self-consciously and comically cosmopolitan options—London Fish & Chips, Fujiyama’s Yakisoba, Man’oushe Street, and Magic Wok. And while London’s Fish & Chips does not aim to cater to British ex-pats, nor does Fujiyama’s Yakisoba aim to cater to Japanese tourists, it was for a taste of home that unprecedented crowds gathered for Jollibee Dubai’s grand opening. Filipinos waited up to five hours to be served a Chicken Joy meal for 7 UAE (~ US $2). While there are many Filipino restaurants in Dubai, the Jollibee is the only Filipino restaurant in the Dubai Mall. Most other Filipino restaurants concentrate around the Al Satwa neighborhood, Dubai’s Filipino-town. In Al Satwa, Filipinos are able to buy Filipino ingredients in local markets and speak Tagalog or Ilocano on the street. It is, in other words, more or less discernable as an “anthropological place,” in Augé’s parlance. Paradoxically, however, it is a place that is in many ways more distinct from the OFWs’ experience of “home” than the Dubai Mall.

To go to the Dubai Mall is to feel the comfort of inclusion and the thrill of the masa in a non-place that looks and feels very much like home—where one can take solace in being one of many, a perverse comfort under the conditions of a double alienation. There, Filipinos can blend in among both tourists and other foreign workers and in that pile find a few fellow travelers. In other words, OFWs are drawn to the Jollibee out of a melancholic nostalgia for belonging to the non-place.

Today, there are countless obstructions that mire our view of the total event of global capitalism, but we may be afforded small glimpses of it by carefully observing the particularities of an architecture that is at once spectacular, ubiquitous, and banal. It is perhaps because of this particular combination of properties that an in-depth consideration of the rapidly multiplying Philippine supermall is left outside of any major work of cultural criticism. An ignorance of the global supermall and its connections to cultures of migration becomes particularly poignant when one considers what is happening in Saudi Arabia, which in a concerted effort to shift its economy away from oil dependency plans to triple its mall space by 2025.20 This is also the case in Iran, which opened the world’s largest mall in 2017; in China, where SM has opened seven supermalls; and in Thailand, which now has two malls with close to six million square feet of leasable area. These developments do not follow upon American examples (where mall space is imploding) but rather follows upon the Philippine model—of the mall as an infrastructural piece of the city and economy. In these places, malls are a mode of interior urbanization.

Concrete supermalls across the globe and their air-conditioned interiors offer less poetic metaphors than Walter Benjamin’s crystalline arcades. In the shadow of supermalls the arcade appears precious, rare, and almost trivial. In his In the World Interior of Capital, Peter Sloterdijk argues that if one were to attempt a continuation of Benjamin’s suggestions for the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, they would require not only a number of indispensable methodological rectifications but also a fundamental reorientation. This would include, Sloterdijk emphasizes, an adaptation to the architectural models of today—“above all the shopping malls.”21 Shopping malls, Sloterdijk writes, are the inheritors of the massive interior, not of the arcades, but of what he believes is the fundamentally distinct space of the Crystal Palace, which Sloterdijk believes Benjamin viewed as nothing more than “a magnified arcade.” 22 In the “gigantic Crystal Palace” Sloterdijk saw a structure that “already anticipated an integral, experience-oriented, popular capitalism in which no less than the comprehensive absorption of the outside world in a fully calculated interior was at stake.” The Crystal Palace, Sloterdijk continues, “… invoked the idea of an enclosure so spacious that one might never have to leave it.” Sloterdijk points to the design of the Southdale Center in Edina, Minnesota, as the origin of this “architectural model.”23 Indeed, when Victor Gruen first designed Southdale, he imagined a medical center, schools, and residences, not just a parade of stores. It was, Gruen believed, an urban idea. But in the United States the mall never achieved this form. Thus, a disjunction exists between the now failing American mall and the still thriving and evolving Philippine supermall.24 The Philippine supermall is a new format, a new structure.

Sloterdijk’s description is a compelling prism through which we can view the object of the Philippine mall—especially if we consider that the population that we are looking at contains, for the most part, the ostensible “losers” of globalization. Those so-called "losers" are those left outside of the metaphorized Crystal Palace, which Sloterdijk describes as the formal equivalent of the invisible and practically insurmountable boundaries of globalization. Taking a self-consciously philosophical stance, Sloterdijk pushes abstraction as a more flexible mode of thought, one he opposes to Benjamin’s “digging for treasure in libraries.”25 As a methodological orientation, however, it leaves us without the ability to think of the particularities of global forms, the twisted topos of a transnational space of belonging to where one cannot possibly belong. For the perpetual migrant—the non-place is where one is habituated to and even experiences comfort with alienation—a space that itself substitutes for “meaningful” social relations (instead of being the site where social relations might be formed). The mall is an infrastructure that shapes and maintains complex cultures of migration. For those trapped between an only illusory “here and elsewhere,” it is by virtue of being a non-place that for many Filipinos, whose lives are defined by cycles of migration, that the supermall feels just like home.

-

Reinhold Martin, The Urban Apparatus: Mediapolitics and the City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Also see Cornelia Vismann, “Cultural Techniques and Sovereignty” in Theory, Culture & Society (Summer 2010): 83–93. ↩

-

Officially, “Overseas Filipinos” is the term that encompasses all Filipino migrants, whether permanent or temporary, legal or unauthorized, while “Overseas Filipino Workers” (OFWs) represents a subset of Overseas Filipinos who work on a contract basis. Despite this official distinction, OFW is the term colloquially used for any Overseas Filipino with Philippine citizenship who sends regular remittances back to the Philippines. In 2013 Overseas Filipinos were divided into three categories: “Permanent,” “Temporary,” and “Irregular.” Permanent migrants include Filipino immigrants and legal permanent residents (4,869,766 in 2013); temporary migrants include documented land-based and sea-based workers and others who stay abroad six months or more, including their accompanying dependents (4,207,018 in 2013); irregular migrants are Filipinos who are without valid residence or work permits, or who may be overstaying workers or tourists in a foreign country (1,161,830 in 2013). The total amounts to roughly 10 percent of the population of the Philippines. Current numbers vary considerably from those reported in 2013, and appear to vastly underestimate the number of Overseas Filipinos by presenting OFW numbers as representative of the total migrant population, see the 2020 report from the Philippines Statistic Authority: link. 2013 figures from the Commission of Filipinos Overseas: link. ↩

-

Aerol John Pateña, “DOTr Inks Deal on Common Station Construction,” Philippine New Agency, February 13, 2019, link. ↩

-

The first area, “Area A,” will be financed, and run by Manila’s Department of Transportation, with the building contract awarded to the BF corporation; “Area B” will be financed, built, and operated by an affiliate of the Ayala Land Corporation; and “Area C,” which will hold the platform for the proposed MRT, will be financed, built, and operated by the SM Corporation. ↩

-

The Quiapo Church is popular among the Philippine masses on account of its housing the Nuestro Señor Jesús Nazareno (the Black Nazarene), a dark figure of Christ carved from black wood by a Mexican artist. The image, reputedly miraculous, was brought to the country in a Spanish galleon in the seventeenth century. ↩

-

Sy quoted in Rigoberto Tiglao, “Strength in Numbers,” Far Eastern Economic Review, July 21, 1994, 60–61. See also Rigoberto Tiglao, “Mall Mogul,” Far Eastern Economic Review, August 31, 1995, 50–51. ↩

-

To a certain extent, this was an old business principle. The success of Paris’s Au Bon Marché, which began to turn huge profits in 1852, was due to a shift in business practices that depended on the principle of “high turnover and small profits,” which, as Walter Benjamin noted, “accorded with the two dominant forces in operation: the multitude of purchasers and the mass of goods.” Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999), 58. ↩

-

By Sy’s logic, if one third of the estimated 300,000 people who visit the mile-long, six-story SM Megamall spends P200 (US $4) each, sales would total P20 million daily, and P7.3 billion annually. This group may not have strong individual spending power, but the strength of sales depends only on their sheer number. Unusually, Sy charges rental fees as a percentage of sales (itself a sliding scale between 3 and 15 percent). This is a situation that allows small businesses to continue to rent, even if they are struggling. Sy argued that the remittance consumer is a very large consumer class and claims that as much of 30 percent of his sales come from it. In short, Sy and his family built their fortune on the marginal profits. See Tiglao, “Strength in Numbers,” 60. ↩

-

Mayvelin U Caraballo, “OFW Rremittances Hit All-Time High in 2019” Manila Times, February 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Richmond S. Mercurio, “SM Assures Mall Goers of Blackout-Free Summer,” Philippine Star, October 23, 2014. ↩

-

Rigoberto Tiglao, “Mall Mogul,” Far Eastern Economic Review, August 31, 1995, 50–51. ↩

-

Forms of exclusion vary from country to country and include everything from guest worker arrangements that contain no path to citizenship, as is the case with Canada’s Live-in Caregiver Program to the now defunct Love Ban in Lebanon, a law that prohibited relationships between foreign live-in domestic workers and Lebanese citizens. On Canada’s Live-in Caregiver Program see, for example Rachel K. Brickner and Christine Straehle, “The Missing Link: Gender, Immigration Policy, and the Live-in Caregiver Program in Canada, Policy and Society 29, no. 4 (2010): 309–320. On Lebanon’s Love Ban, see Sumayya Kassamali, “Migrant Lifeworlds of Beirut” (PhD dissertation, Columbia University, 2017), link. ↩

-

The social toll of Philippine migrant labor has been for some time a matter of national policy. The social reintegration of OFWs has become a key policy initiative of Philippine welfare programs. OFW—Reintegration Program, See “Reintegration Program,” Department of Labor and Employment: Overseas Workers Welfare Administration, link. ↩

-

Augé argues that for the ethnologist, the Western “here” historically assumed its full meaning in relation to the distant elsewhere—a formerly “colonial,” now “underdeveloped” world. An anthropology of supermodernity—one that can fully describe non-places, requires an examination of cultures no longer tied to a fixed time and space. See Marc Augé, Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity (New York: Verso, 2009). ↩

-

There is a great deal of literature on this topic. See Robyn Magalit Rodriguez, Migrants for Export: How the Philippine State Brokers Labor to the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); and Anna Romina Guevara, Marketing Dreams, Manufacturing Heroes: The Transnational Labor Brokering of Filipino Workers (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010). ↩

-

Eric Le Borgne, “Remittances and the Philippines’ Economy: The Elephant in the Room,” World Bank Blogs, April 7, 2009, link. ↩

-

Claire Denis S. Mapa, “Statistical Tables on Overseas Filipino Workers,” Philippine Statistics Authority, June 4, 2020, link. ↩

-

Virtually all Filipinos who work in Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE enter under the auspices of the Kafala system, a framework used to monitor migrant laborers, working primarily in the construction and domestic sectors. The system requires all unskilled laborers to have an in-country sponsor, almost always their employer, who is responsible for their visa and legal status. This practice has been criticized by human rights organizations for creating easy opportunities for the exploitation of workers, as many employers take away passports and abuse their workers with little chance of legal repercussions. See, for example, Amrita Pande, “‘The Paper that You Have in Your Hand Is My Freedom’: Migrant Domestic Work and the Sponsorship (Kafala) System in Lebanon,” International Migration Review 47, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 414–441; and Rachel Salazar Parreñas and Rachel Silvey, “Domestic Workers Refusing Neo-Slavery in the UAE,” Contexts 15, no. 3 (Summer 2015): 36–41. ↩

-

Abbas Al Lawati, “The Saudis Want Pilgrims to Spend More Time Shopping,” Bloomberg, September 23, 2018, link. See also Khalid Al-Jasser, who in 2017 became the CEO of Arabian Centres (the biggest mall operator in Saudi Arabia) and came to the mall industry after a long career in investment banking. The mall, Al-Jasser states is part of a strategy to “transform economy and society … and is at the forefront of social change.” One of the social reforms that has become a central lobbying point for mall developers is the employment of Saudi women at malls. This is part of a large-scale shift toward developing a labor economy (oil extraction and exportation do not rely on large working masses). Saudi Arabia is a vast welfare state where all social services are heavily subsidized. The entire economy is based on the projection not only of the continuous availability of oil but also on the projection that oil prices would remain relatively stable. Thus, a shift toward an economy based in consumption, and the “liberal” reforms that will inevitably come along with it, is one of the ways in which the House of Saud is attempting to maintain its power. See Frank Kane, “‘Saudi people want to shop in the mall, not from their computer,’” Arab News, April 10, 2017, link. ↩

-

Peter Sloterdijk, In the World Interior of Capital (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2017), 244. ↩

-

While I agree that the Arcades and the Crystal Palace are different, I disagree with Sloterdijk that Benjamin only saw a very large arcade in the Crystal Palace. Though Benjamin was never able to complete the Arcades Project, one could sense a sort of foreclosure of the dialectical possibilities of the Arcade with the advent of Les Grands Magasins. Benjamin points out that the establishment of Credit Mobilier (for financing railroads), and of Credit Foncier happens in the same year (1852) as a major financial reorganization of Au Bon Marché. In 1852, total sales for Au Bon Marché were only 450,000 Francs; by 1869 they had risen to 21 million (Benjamin 2003, 46). Perhaps this had little to do with the fact that Au Bon Marché’s patterned and polychromatic glass ceiling was too dazzling for one to discern that it, too, was structured by iron. But the amount of capital required to specify such elaborate architecture allows one to draw a straight line from the connections between finance capital and a sensuous experience of space. “Le Mécanisme de la vie modern: Les Grands Magasins,” Revue des deux mondes, 124 (Paris, 1894), quoted in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 335–336 and 732. ↩

-

Sloterdijk, In the World Interior of Capital, 173. ↩

-

Victor Gruen, Shopping Town: Designing the City in Suburban America, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 152. ↩

-

Sloterdijk, In the World Interior of Capital, 174. ↩

Diana Martinez is an assistant professor of architecture history and the director of Architectural Studies at Tufts University. She is completing a book manuscript, Concrete Colonialism: Architecture, Infrastructure, Urbanism, and the American Colonial Project in the Philippines.