In the land where both “Corporations are People”1 and “All Lives Matter,”2 “Human Resources” may strike us as a thing we have somehow always lived with, as if measured productivity was an essential feature of human existence. But the invention of the term and its infiltration into the labor imaginary is a thoroughly modern development. The human resources project that unfolded in the twentieth century—from the marshaling of a civilian workforce in times of national crisis to the development of ever more employable individuals—is one that actively conflated the terrains of life and labor into a science. The paradigm of personnel management that emerged in prewar factory production became naturalized within late twentieth-century offices and institutions as “HR.”3 The acronym, a fixture of the corporate lexicon that has invaded the cultural imaginary of work, effectively collapses the objects and infrastructures of employment, such that the humanity of individual workers can be weighed against their quantifiable value to the organization that employs them, and in relation to an external pool of potential recruits that might replace them. In this frame, human resources are simultaneously reified as people and as capital—the live objects of social expenditure or personal investment, and the infinite reserves to power an ever-expanding market.

If it took the previous century for this concept to cohere, the first decades of the twenty-first would expose its precarity. The imbrication of global financial crisis, decreased social spending, and growing income inequality showed that HR wasn’t as fungible as it had seemed.4 Meanwhile, employment has retained its moral imperative, and it remains a measure of the health of the national economy. By this year—the long 2020—converging crises have thrown “valuable” human resources into much higher relief: who works the “front line,” who will remain at home, who qualifies for aid, who will have to assemble in the streets, who will do the work that lies ahead, and who has not been considered at all.5 As I write this text, friends working in architecture have been furloughed, let go, or asked to take pay cuts while their employers weather a pause in production and adapt to the economic and logistical fallout of the global COVID-19 pandemic. New graduates of design programs have found themselves plunged into an impossible job market, being invited in their apparent downtime to participate in ideas competitions about the new design problem of “social distancing” or an old favorite, the prison.6 These are the unsurprising activities of a majority-white profession that has tricked itself into thinking it can solve the world’s problems from without, while remaining beholden to a ruling class whose refusal to provide affordable housing, accessible public space, and other well-serviced public infrastructures has contributed to an untenable material reality for so many. The neoliberal drift of HR similarly divides the working world, reproducing racial disparities as it announces ever new diversity and inclusion measures to overcome them.

As the virus and rising unemployment have exacted asymmetrical burdens on Black Americans, subject to both social abandon and state-sanctioned violence, human contingencies have been reilluminated by burning buildings.7 From afar, talking heads debate the validity of demonstrations that engage in looting and the destruction of property, forcing a value comparison between architecture and Black lives. Up close, the proximity of masked demonstrators to one another registers as a risk willingly taken (a risk otherwise consigned to workers deemed essential)—dangerous but less so than the exposure to police forces outfitted in riot gear and decommissioned military equipment.8

Activists have condemned police brutality and associated conditions of resource abandonment in explicitly architectural terms.9 Insufficiencies across the provision of housing, public transport, and street upkeep, among other urban improvements, are all the more obvious at the protest, when the full resources of city security are on display. In Chicago, this withholding of public infrastructure was mirrored in the raising of all but one bridge around its downtown Loop: a tactical maneuver to trap protesters just as Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced a curfew during protests on May 30.10 Phalanxes of police, typically the primary beneficiaries of municipal expenditure, were deployed in Chicago, New York, Minneapolis, Lexington, and other cities across the country to manage assemblies, deeming them unlawful at the moment they appear to endanger property. Cable news images of shattered or boarded storefronts illustrate the distinctions made between a “peaceful protest” and the implicitly unjustified riot. When the Third Precinct of the Minneapolis Police Department was overtaken by protesters on May 28, a local journalist described the expropriation and destruction on Lake Street euphemistically as people “interacting with materials.”11 Architects scandalized by the immolation of a nearby construction site were less delicate in their appraisals of these actions (“Buildings Matter, Too”).12 The neighborhood where George Floyd was killed would sustain some of the greatest physical damage over the course of nationwide protests, but the events in Minneapolis would occasion the most immediate transformation of government, as the city council moved to defund its police force just weeks later.13

Old Houses

The constructive metaphors wielded by pundits—building bridges, mending fences—prioritize reform where the crisis of white supremacy endures. Maintenance efforts seem to suggest a more productive way forward than simply burning the house down. If America is an old house, in the way that Isabel Wilkerson applies the metaphor to see the invisible infrastructures of racial hierarchy, this work will never be done.14

At home, where many still remain, Americans entertain background noise to the social media wellspring of protest imagery. On PBS, for example, a white family renovates their Rhode Island ranch house into a Dutch colonial on the show This Old House.15 But the quaint public broadcasting that secures viewers in homebound times is a fragile picket fence. The episode highlights a program in which young apprentices shadow contractors and subcontractors to gain on-site experience in building trades.16 One trainee, Kathryn Fulton, kneels to apply paint to wainscoting, under the supervision of “Master Painter” Mauro Henrique, matching her work to the homeowner’s sample of white-washed knotty pine salvaged from the original house. “It’s pretty spot-on to me,” she says.17

These concurrent realities force a split screen of two Americas: one building a new-old colonial house on public television and another struggling to breathe in public space. This disparity highlights the work yet to be done, but it also pulls on the many entanglements between life and work that are designed to maintain the structures of white supremacy even under the guise of progressive reform.

The Generation NEXT apprentice program on display in This Old House appears to be a novelty, but it follows a legacy of jobsite training as social program that extends back to the Manpower Administration of the 1960s led by Labor Secretary Willard Wirtz. By 2016, a generation of builders were steadily aging out of the trades, and contractors’ concern regarding a diminished pool of skilled labor gave cause for training young people to replace them. Generation NEXT is funded through the private foundation mikeroweWORKS (Mike Rowe of “Dirty Jobs” fame) and the homebuilding industry nonprofit Skilled Labor Fund, an initiative of the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). The NAHB has its own history of sponsoring apprenticeship programs, some of which received funding through Department of Labor contracts under the Manpower Administration.18

Building the Corps

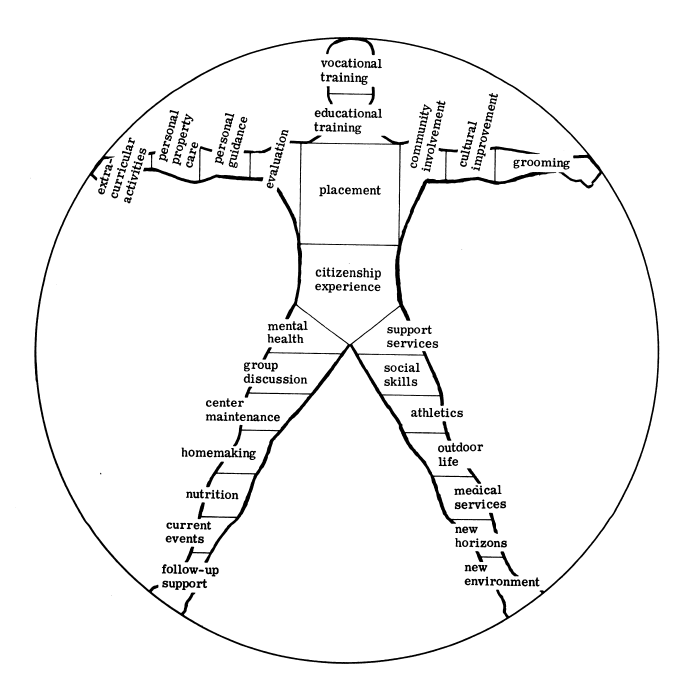

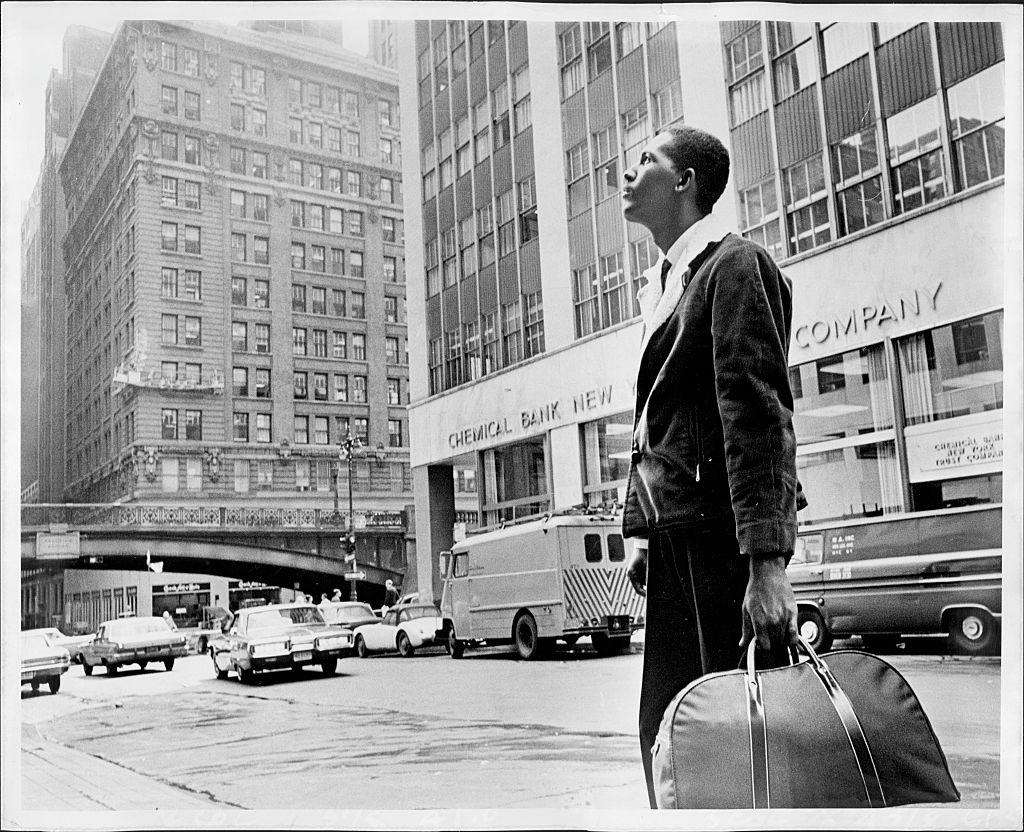

“Manpower”—eventually replaced by the gender-neutral “human resources”—became a focus of executive action under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who considered it a tool for national economic planning.19 Formalized under the Department of Labor with the passage of the Manpower Development and Training Act (MDTA) in 1962, it coincided with the institution of new social welfare programs under John F. Kennedy. During the 1960s, the federal government pursued large scale initiatives to increase the employment of Americans across the country as cities underwent urban renewal. “Idleness” and “blight” were seen as inextricable conditions of poverty, which could be solved by jobs and job training.20 One such initiative was the Job Corps, established in 1964 as part of Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society,” specifically employed as arsenal in the “War on Poverty.”21 From 1964 to 1968, more than one hundred Job Corps Centers were coordinated through the Office of Economic Opportunity.22 Secretary Wirtz had actively sought jurisdiction for the initiative within the Department of Labor and pursued a corresponding program, the Neighborhood Youth Corps, as his own personal project.23 Both set out to employ the underemployed youth of the nation, particularly those who came from poor communities and “broken homes.”24

The experts appointed to research and implement Manpower policies would frequently pathologize the state of the city and its “minority” inhabitants, particularly urban youth. The apparently “hopeless” situation of Job Corps recruits, ostensibly verified by low graduation rates and single-parent households, accorded with the theory that antisocial behavior was visible in the urban environment.25 “Broken windows” policing, an ongoing practice given a name in the 1980s, not only conflates urban blight with criminal behavior and people of color with latent criminality, but it suggests that poverty is a spatial product of the poor and not a condition of disinvestment, structural racism, and aggressive policing.26 The Movement for Black Lives is still resisting its perilous effects in 2020. In the 1960s, the Job Corps and Neighborhood Youth Corps intervened to “save” youth from environments in which both crime and poverty were seemingly inevitable. Where public education had failed them, other programs were devised to model civic participation.27

As the New York Times reported on the Neighborhood Youth Corps in 1964, Wirtz situated the neglected youth of America as objects of federal conservation and development—a national resource like any other:

Mr. Wirtz described the corps as “one of this nation’s most ambitious and positive efforts in the conservation of the talents and development of the skills of our neglected young people.”

“Most young Americans are well off,” the Secretary said. “They go to good schools. They have promising futures. But far too many others have been born on a dead end street. For these—the unskilled seeking work in a computer age, the children being raised in poverty, the young men and women struggling against slum environments—the economic progress of this nation is a meaningless set of statistics.”28

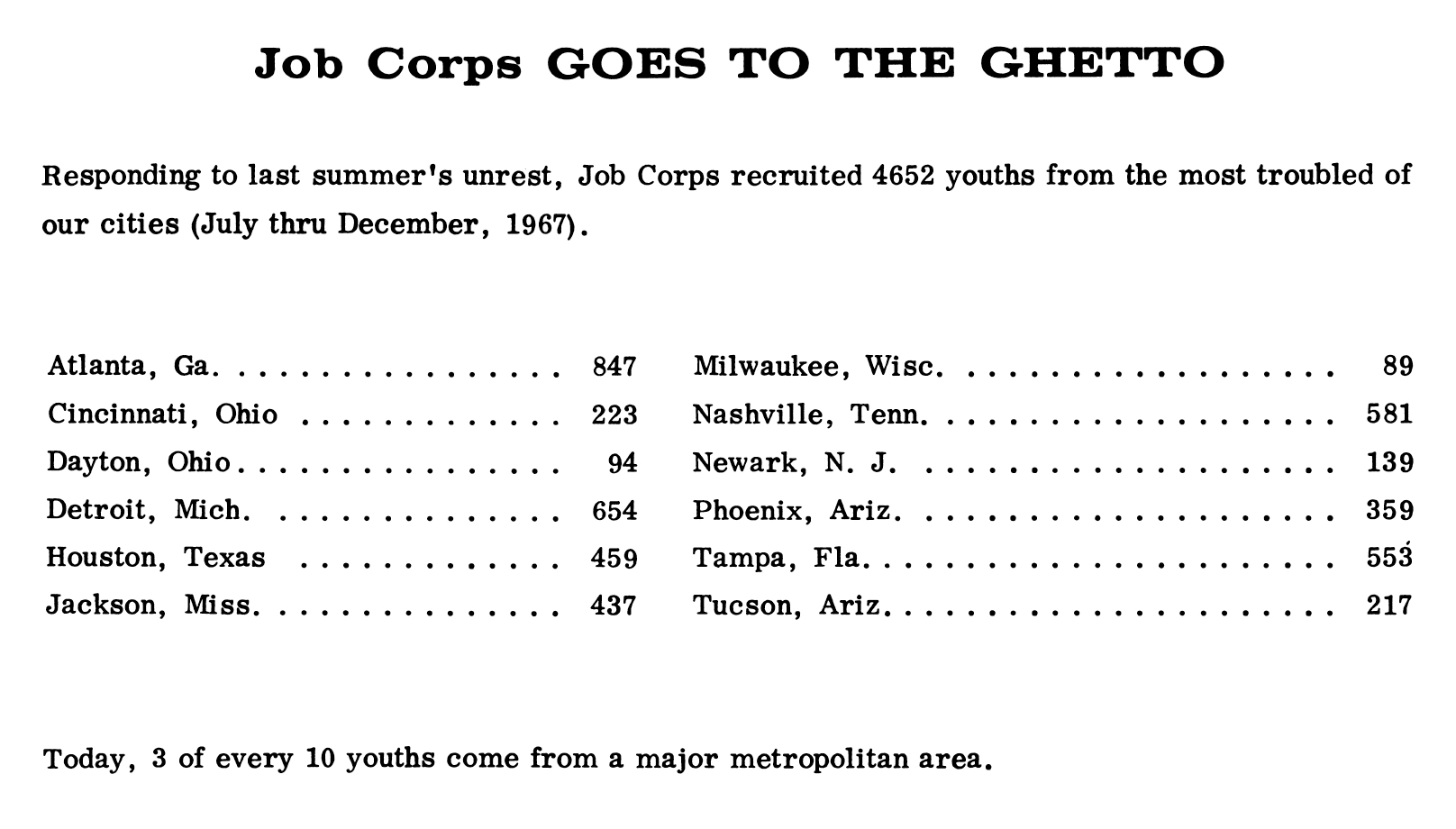

But both programs were enacted to offset what would be cast in statistical terms. Though the Job Corps did not initially account for race or ethnicity in its official reports on program participants, its declared objective was the betterment of youths “black or white, Mexican-American, Indian or Puerto Rican, rural or big city ghetto.”29 That betterment was not simply for its own sake but directed to fashion good citizens. In a report on the first three years of the program’s operation, the Job Corps member was compared to the “typical rioter,” asserting a correlation between those who grew up in substandard housing and those who would occupy the streets to make political and material demands, here understood as rioting.30 Job Corps training was not only organized to diminish poverty but also expressly intended to prevent the development of unruly political subjects.

The Job Corps was a residential program for fourteen- to twenty-one-year-olds—meaning that, as an alternative to high-school education, high-school-age youths worked and lived at work camps, sometimes very far from their hometowns. Their removal from their home environments was considered an integral part of their “rehabilitation” through work.31 The Neighborhood Youth Corps, by contrast, allowed participants to live at home and attend vocational programs in lieu of or in addition to traditional schooling. Both positioned vocational education as environmental—either by working away from or precisely within communities of need—such that its participants would be able to work their way out of urban poverty or transform their surroundings by their own socialization through work.

Representing Manpower

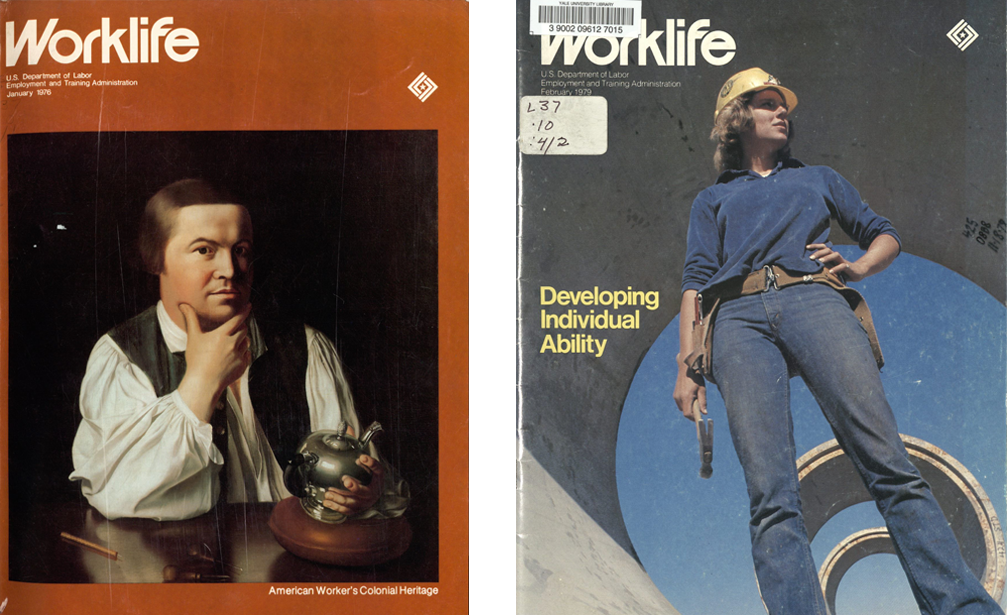

The legacy of these job training programs as a solution for intractable social problems was affirmed in the Department of Labor’s own publications. The titular journal of the Manpower Administration, Manpower (1969–1975) and its later guise Worklife (1976–1979), set out to represent a changing landscape of American work in unsteady times while enforcing the redemptive value of employment. “Manpower,” like the multivalent figure of human resources, was defined broadly in ads that ran in the journal’s issues: inclusive of “people, jobs, poverty, employment and unemployment, transportation, education, economics, housing, training, health services, upgrading, apprenticeship, research.”32 Recognizing the diversity of these human resources and the expansive activities through which a working citizenry is cultivated, including the reformist idiom of its own articles, Manpower’s representational efforts set out to actively reshape the image of the American worker to include Black women and men, mothers, the formerly incarcerated, migrants, disabled people, the “hard-core unemployed,” and many others who had served as specific socioeconomic targets for Department of Labor and Anti-Poverty programs.33

The human resource issues that emerged in the 1970s were framed around the specific skills and infrastructures needed to overcome contemporary crises—social unrest, technological upheavals, environmental change, and economic recession—and implicated both individual and collective responsibilities.34 As an effect, Manpower literature and policy enjoined the provisionally employed person to not only overcome their own disadvantage but also to transform the very terrain of work where they might have fuller livelihoods.

In 1970, Manpower published an article titled “Rebuilding the Ghetto from Within,” describing the renovation of Washington, DC’s Clifton Terrace Apartments, middle-income housing that, having fallen into disrepair, had become an emblem of urban blight for would-be reformers.35 The piece conflated the inner-city with Blackness and suggested that property upkeep was an intractable problem for white “slum landlords [who] simply became over-extended or discouraged” but were not directly responsible for poor living conditions.36 Renovations at Clifton Terrace came only after existing tenants had organized, refusing to pay rent to a landlord who left the apartments unmaintained and without heat.37 But as a display of Manpower dollars at work, the article understated the impact of the historic rent strike and instead emphasized the role that Black construction labor would play as a model for low-income housing rehabilitation across the nation, involving training unskilled workers from the neighborhood and coordinating union membership for non-union tradesmen. On-site instruction for new construction workers was presented as a public benefit not unlike subsidized housing, but Black workers would perform the visible work of transforming both majority-white building trades as well as the dilapidated building. Unfortunately, it would not be enough to restore the potential of the original garden city apartments, which would see continued mismanagement for decades, leading the Department of Housing and Urban Development to relinquish the property to developers in 1999 for one dollar.38 Since it was converted to condos, many of its long-term residents have been priced out of the complex and the neighborhood—though the building remains a stop on a civil rights city tour organized by the DC Historic Preservation Office.39

Natural Resources and Human Resources

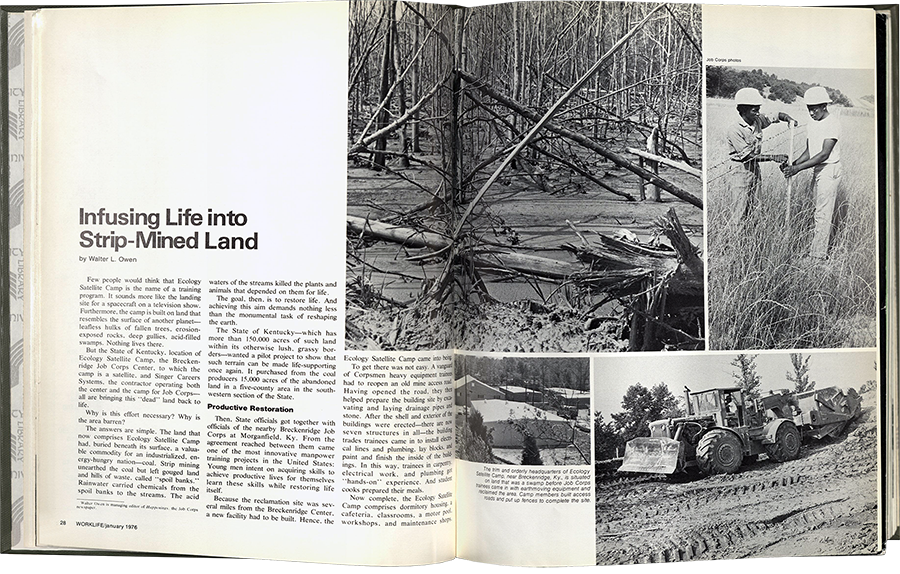

While Manpower and other literature promoting Department of Labor programs collapsed an impoverished Black subject onto blighted cities, a corresponding sense of “ecological surplus” fueled contingencies between newly mobile workers and a useful environment.40 A 1971 article “Into the Forest and Out of the Woods,” described the impact of Operation Mainstream, a two-year training program that put undereducated and chronically unemployed adult men to work building trails, performing fire control operations and “environmental beautification” in order to teach masonry, carpentry, and other skills. As the author put it, “Human resources develop natural resources. But the reverse is also true. Some of America’s most valuable natural resources, our national forests, are being used to develop our human resources.”41 An article in the 1976 issue of the magazine, by then reformatted under the title Worklife, asserted similar productive life cycles in environmental rehabilitation: “Infusing Life into Strip-Mined Land” covers a Job Corps satellite camp in Kentucky, where environmental reclamation of “dead land” laid bare by the surface mining of coal was performed by young Corpsmen, temporary residents of the camp they were enlisted to construct.42

These projects, built on the foundation of the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, emphasized the reciprocal nature of work in the environment and on the self. Good citizenship and good work were benefits triangulated with the moral cause of environmental stewardship. These virtues have been renewed more recently in the Climate Conservation Corps, a proposed “reinvigoration” of AmeriCorps or resuscitation of the former Conservation Corps, included in the policy platforms of progressives like Bernie Sanders and centrist Democrats like Joe Biden.43 A new national service summoned to combat the outsize effects of environmental crisis still centers workforce education and participation in a clean energy economy. Such an initiative would necessarily employ “a vast army of young people,” who might personally benefit from other forms of public service and alternatives to higher education.44 State-sponsored action, now addressed to an ecological future or to pandemic survival, again finds its reserves in young people who, at least in the immediate term, need the work to survive.

In the 1970s, Manpower and Worklife would continue to implicate the utility of natural resources in the development of human resources, shifting between environmental efforts for conservation and extraction. The construction of the Alaska pipeline,45 solar energy installations,46 and efforts to mitigate “energy waste”47 were a few of the energy-related projects covered by Manpower and Worklife that would make use of idle workers and deliver technical experience for their continued participation in energy industries. Jason Moore has described this phenomenon in postwar America as a kind of extractive imaginary that did not only rely on the supposed cheapness of raw materials, like rubber, coal, and oil (although the latter resource would be thrown into crisis by 1973), but the undeniable “socio-ecological character of surplus, which comprises not only food, energy, and raw materials but also human nature as labor power and domestic labor.”48 Building on Moore’s trajectory of cheapening nature in the Capitalocene and Cedric J. Robinson’s writing on racial capitalism, political theorist Françoise Vergès has more recently reframed the questions of environmental racism—the racialized nature of pollution—to center race in the making of the Anthropocene. “What connection can be made between the Western conception of nature as ‘cheap’ and the global organization of a ‘cheap,’ racialized, disposable workforce…?”49 Incorporating slavery and other appropriations of Black labor into a history of the environment aligns the devaluation of natural resources with the devaluing of work performed by specific people—humans as resources.

Progress at Work

The Department of Labor would continually resort to presiding narratives in American history to evaluate the larger project of labor-in-transition, couching its efforts to overcome a fundamentally unequal employment landscape in references to shining moments of national progress.50 Slavery, too, would be acknowledged as part of this history, if only to claim the event of emancipation as a triumph against labor exploitation in the agricultural south.51 Though Manpower sharpened the rhetorical divide between the department's urban and rural initiatives—in articles whose illustrations also made clear the divided racial focus in its regional programming—the journal repeatedly asserted contingencies between the provision of good work and the use of labor toward greater ends (reduced crime, better housing, cleaner rivers). In that vein, Manpower’s articulation of a history of human efficacy alternated between statements of collective freedom and of personal change. Secretary Willard Wirtz opened the first issue of Manpower in January 1969 with a quote from Abraham Lincoln: “It is in order that each of you, through this free government, has an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence…”52 The emancipatory premise of his editorial note positioned the work of the Manpower Administration as enabling the individual ambitions of men in work, in entrepreneurial pursuits, and in the skills or natural talents that might qualify them for either. And so, for Wirtz, the changing nature of this “open field,” relied on federal investment in the mechanisms by which Americans could participate in their own human resource development.

Following the passage of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973 (CETA), the Manpower Administration was rebranded as the Employment and Training Administration in 1975, a move that was followed by the conversion of Manpower to Worklife. The inaugural issue of the new edition in January 1976 recommitted to the mission set forth by Wirtz in 1969: “to advance national efforts to equip every American for meaningful employment” but in terms that would keep pace with a “changing economy and society.”53 In casting a new era in which to pursue many of the same efforts brought by the Manpower years, including removing its titular “reference to sex,” Worklife attempted to find neutral political ground in “meaningful employment” and in a culture of work that extended back to the American Revolution (this was a bicentennial edition, after all).

The nature of the exchange of Manpower for Worklife rested more visibly—or perhaps more comfortably—on the greater employment of women, and on a refusal of the uncompensated labor of housework for the representation of women within the formal realms of capitalist production.

The second to last issue of Manpower in November 1975 was temporarily reformatted as Womanpower, a project led by Gloria Stevenson, the deputy editor under Manpower’s chief, Walter Wood. As she wrote, International Women’s Year (so it was in 1975) presented an opportune time to feel all the “pain of transition” necessary to achieve equality. Women would have to break out of socially expected roles, often for underpaid work, while men, presumably white men, would bear whatever discomfort might come of women’s “rising status in the workplace.”54 White women exemplified the personal prerogatives of equality that could be redeemed in offices and on job sites where their assimilation was a political choice tied to liberation.

Solutions came by way of executive exchange programs, on the one hand, and those like the Work Incentives Network (WIN) program, on the other, which was developed to get people off of welfare and into better paying jobs. In 1974, WIN’s training operations were devised by the Center for Human Systems Inc. through a contract with the not-yet-renamed Manpower Administration, and the majority of its participants were Black women. The story that appears at the end of the thematic issue Womanpower invokes Rosie the Riveter and leads with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s quotable solution to the shortage of wartime labor resources: “We have no manpower problem. We have womanpower.” Accordingly, work was to be understood as a kind of national duty, here reframed as women’s “independence” from welfare.55

But as Angela Davis points out in 1981 in Women, Race and Class, Black women have not been subject to the same kind of exclusion from the workplace that would frame white women’s appearances in it as alternately patriotic or empowering. Davis argues that Black women’s longer durée in American labor was not consistent with the notion of feminist progress as tethered to compensated work.

Throughout this country’s history, the majority of Black women have worked outside their homes. During slavery, women toiled alongside their men in the cotton and tobacco fields, and when industry moved into the South, they could be seen in tobacco factories, sugar refineries and even in lumber mills and on crews pounding steel for the railroads. In labor, slave women were the equals of their men. Because they suffered a grueling sexual equality at work, they enjoyed a greater sexual equality at home in the slave quarters than did their white sisters who were “housewives.”56

The abolition (rather than socialization) of housework could only be enjoyed by women who thought paid domestic work to be outside of their present political reality, not having worked as nannies, maids, and caretakers—jobs filled by women who have long performed reproductive work outside of their own homes. In her 1980 book Black Women in the Labor Force, the economist Phyllis Ann Wallace suggests that Black women’s employment had been “continuous and high” in the twentieth century but pointed to the double burden on Black women to perform waged work, often as primary earners, and uncompensated housework.57 White professional women sheltering-in-place in 2020 are fortunate to work from the homes that their mothers sought liberation from in the 1970s, even if they are overburdened by the task of twenty-four-hour childcare. But that working environment is much more complicated for the nannies and cleaners that they pay, or have since let go, who also go home to families of their own.58

Work or Life

Essential work is not heroic; just ask the striking workers of your local Amazon fulfilment center.59 And participation in the labor force is a faulty measure of progress, especially when one’s survival depends on that labor. The Department of Labor only ever implemented reforms that inscribed state support within the logics of compulsory work. Its publications endowed federally funded training programs and initiatives for provisional employment with all the promise of a better life and a more equitable American future, but it would ultimately be the responsibility of individual workers to first build this future for themselves.

A “Great Society” based on jobs alone was delivered in the absence of the environmental supports that would actually maintain the health and capabilities of would-be workers. Meanwhile, problems of social abandon and cheapened human resources were displaced in the capitalist imaginary as symptomatic of, rather than embedded in, the logics of racial capital. As a result, the journals pathologized Blackness in terms of employability and poverty.60 The commingled projects of governing productive subjects and ensuring capital accumulation have persistently made Black lives and Black cities the objects of improvement, objects to be more readily assimilated to the demands of capital. The history of slavery is preserved here, and it bears repeating what should always have been self-evident: Black lives matter.

The Job Corps has continued to operate its training centers and labor camps over the last six decades, maintaining bipartisan support for funding if not delivering on its mission to raise employment and improve the earning potential of its graduates.61 So what does it mean to reauthorize the mission of a national corps (for jobs, climate, peace, or public health) or to offer potential corps members field experience or an associate’s degree equivalent in exchange for a future upon which survival on earth depends? What is there to be gained from individual or state-supported skill-building by a generation whose productivity has been internalized into deeper arenas of self-improvement and requisite self-care and even further from the provisions of the state? Work has ceased to be redemptive, if it ever was (“N-Y-P-D: QUIT-YOUR-JOB,” protesters yell outside the 81st Precinct in Brooklyn).

We—the we formed through insurrection and isolation, essential work, and unemployment—must demand something other than a salary from more benevolent human resource managers. And we certainly cannot continue down a path that promises “economic independence” as an individual pursuit and national ethic—conflated as they are in the neoliberal paradigm—because for so many, that “independence” comes without a living wage, health care, secure housing, or protection from exploitation: the benefits elsewhere conveyed through classed “HR.”62 The perpetuity of these inequities in work through the pandemic and economic shutdown has revealed the bare frame of support that people need to function, interdependently.

Social reproduction—which continues to be un(der)compensated as its own labor or is newly accounted for among the generosities of corporate provision—must be recovered from the human resources project. Ordinary citizens and noncitizens have already taken responsibility for the distribution of mutual aid and physical defense of communities served otherwise by heightened police presence.63 While a Republican-controlled Senate weighs the cost of temporary unemployment benefits (as a deterrent to risky, minimum-wage employment), we have to resist the enforcement of work at the expense of our lives and remain in solidarity with those who cannot choose.64 These crises have brought together a broad coalition of reformers, rioters, and those who’ve survived in the presence or absence of progressive social policy. If ever there was a moment of liberation to be seized, it is precisely at this time that we should wrest our human supports from the tangled web of capital that has always viewed human labor as a site of extraction.

-

Nina Totenberg, “When Did Companies Become People? Excavating the Legal Evolution,” NPR, July 28, 2014, link. ↩

-

George Yancy and Judith Butler, “What’s Wrong With ‘All Lives Matter’?” New York Times Opinionator Blog, January 12, 2015, link. ↩

-

The National Cash Register Company of Dayton, Ohio, is credited with establishing the first on-site personnel department, though the term wouldn’t have been in common use at the time. For a factory of 6,700 employees, the department served as a Fordist layer of organization between management and the workforce. See Elspeth H. Brown, “Welfare Capitalism and Documentary Photography: N.C.R. and the Visual Production of a Global Model Factory,” History of Photography 32, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 137–151; The formalized profession and study of personnel management can be traced back to one of its first journals in the United States: Personnel, which began its publication as a bulletin of the Association of Employment Managers in 1919. ↩

-

Dave Gilson and Edwin Rios, “11 Charts that Show Income Inequality Isn’t Getting Better Anytime Soon,” Mother Jones, December 22, 2016, link. ↩

-

Frank Shyong. “Column: Why did no one warn the housekeepers about the Getty fire?” Los Angeles Times, November 4, 2019, link. ↩

-

See the since-amended and canceled competition “The Architecture of Prisons,” Bee Breeders, link. ↩

-

Vicky Osterweil, “Burning Down the 3rd Police Precinct Changed Everything,” The Nation, June 12, 2020, (link: https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/police-precinct-minneapolis](https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/police-precinct-minneapolis text: link). ↩

-

Police brutality is a public health crisis to be weighed against the risks of assembly during the COVID-19 pandemic. See Justin Feldman’s analysis of the public health risks of racialized police violence in 2015, when protesters were saying the names of Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Michael Brown. Justin Feldman, “Public health and the policing of Black lives,” Harvard Public Health Review (Summer 2015): 7. ↩

-

In Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s terms, resource abandonment produces “forgotten places” that are neither urban nor rural but replete with constraints on social and economic mobility that shape the foundations of the carceral state. Gilmore, “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning,” in Charles R. Hale, ed., Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 34–36; And as Zach Mortice observed at a Chicago protest on June 1, 2020: “The speakers at this protest are framing inequity in explicitly architectural terms: extreme differences between the care and upkeep of buildings, streets, and infrastructure on the north and south sides,” link. ↩

-

Kelly Bauer, “Chicago Calls In National Guard After Night of Protests, Damage Downtown,” Block Club Chicago, May 31, 2020, link. ↩

-

Aren Aizura, who quotes the unnamed journalist, attributes this phrasing to “Midwestern understatement.” “A Mask and a Target Cart: Minneapolis Riots,” New Inquiry, May 30, 2020, link. ↩

-

Adding to the unfolding conversation on Twitter, after the Philadelphia Inquirer published a piece of criticism by Inga Saffron under the headline “Buildings Matter, Too,” Ariana Bellanton argued, “Activists cannot both decry disinvestment in minority communities, lack of quality affordable housing, food deserts, gentrification, inadequate healthcare, and in the same breath say the buildings that house those resources are ‘just property.’ No buildings, no resources,” link. ↩

-

Farah Stockman, “‘They Have Lost Control’: Why Minneapolis Burned,” New York Times, July 3, 2020, link. City Council Vice President Andrea Jenkins, who represents Ward 8 where George Floyd was killed, is one of the council members dedicated to finding community-based alternatives to policing. Jon Collins and Brandt Williams, “After pledging to defund police, Mpls. City Council still rethinking public safety,” MPR News, October 28, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Wind, flood, drought, and human upheavals batter a structure that is already fighting whatever flaws were left unattended in the original foundation.” For Wilkerson, the dilapidated state of the metaphorical house is owed to its original, unequal structure but also its continued negligence. Like the foundation we cannot see, caste is the “underlying grammar” of inequity in America. Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (New York: Random House, 2020), 15–18. ↩

-

This Old House, “Pining for Old Pine,” Season 41, Episode 10, January 12, 2020. ↩

-

Generation NEXT recruits have been predominantly white, but two Black apprentices were selected for this season: Kathryn Fulton and De’Shaun Burnett. “Meet Our Season 41 Apprentices, Kathryn and De’Shaun,” This Old House, link. ↩

-

“Pining for Old Pine,” 10:48. ↩

-

A 1971 issue of Manpower features a carpentry program led by the NAHB and funded through the Department of Labor under the Manpower Development Training Act (MDTA). “Building New Carpenters,” Manpower 3, no. 10 (October 1971): 13–18. ↩

-

Eisenhower inaugurated the Conservation of Human Resources Project with the economist Eli Ginzberg at Columbia University in 1950, where he served as president before his US presidency. Eisenhower intended to study the disqualification of men from active military service, but the research between the Conservation of Human Resources Project and the National Manpower Council (also established at Columbia in the 1950s) would expand to cover manpower issues in both civilian and public service. Columbia University Central Files: Series I, 1895–1971 [Finding Aid], Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Columbia University. ↩

-

The Employment and Training Administration was established with the passage of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), signed into law by Richard Nixon in 1973. ↩

-

Worth mentioning is The Real Great Society of the East Village, made of individuals who banded together to “fight poverty rather than each other to address unmet educational, cultural, and community needs,” with the support of Columbia University architecture students and The Architect’s Renewal Committee in Harlem (ARCH). Roberta Washington, “The Real Great Society,” from the exhibition, Now What?! Advocacy, Activism and Alliances in American Architecture since 1968 (Architexx, November 2018), link. ↩

-

“6 Men’s Centers in 6 States, 18 Women’s Centers in 17 States, 82 Civilian Conservation Centers in 35 States, 3 Special Demonstration Centers in 2 States and the District of Columbia,” Job Corps Reports (Washington, DC: Office of Economic Opportunity, April 1968), 6. ↩

-

Sar A. Levitan, “Examination of the War on Poverty,” Committee Prints, United States Congress Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1967), 4. The Job Corps was officially delegated to the Department of Labor in July of 1969. “President Urges ‘Searching’ Probe of Ways to Combat Poverty,” Manpower 1, no. 4 (May 1969): 32. ↩

-

Job Corps Reports, 11. See a genealogy of “blight” in Andrew Herscher, “Black and Blight,” in Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, eds. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis III, Mabel O. Wilson (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 291–307. ↩

-

As the program is introduced: “The Job Corps task is not an easy one. Job Corps must convince youth that they can change their lives. They have known only failure, degradation, and ignorance. The typical enrollee comes from a broken home, drops out of school after nine years, cannot read a newspaper or magazine, and has no hope of qualifying for employment. His horizons do not extend beyond the despair in which he exists. Job Corps represents his last chance. Without a Job Corps program, thousands of youngsters face continued poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, delinquency, and hopelessness.” In Job Corps Reports, 3. ↩

-

The sociologist Alex Vitale puts it this way: “the broken-windows theory magically reverses the well-understood causal relationship between crime and poverty, arguing that poverty and social disorganization are the result, not the cause, of crime and that the disorderly behavior of the growing “underclass” threatens to destroy the very fabric of cities.” Alex Vitale, The End of Policing (New York City: Verso, 2017). ↩

-

Interviewing Almeda Jackson, a participant of the Neighborhood Youth Corps in East Harlem, reporter Ted Thackery remarks, “You seem perfectly poised to me. If you weren’t before, you must have been taught well.” “How’s the Neighborhood Youth Corps Coming?” April 15, 1965, radio broadcast, New York Public Radio Archives, link. ↩

-

“New Youth Corps Started by Wirtz Offers Part-Time Jobs and Training in Neighborhoods,” New York Times, November 20, 1964, link. ↩

-

A later evaluation of the Job Corps among other Poverty Programs would be more explicit about the demographic focus of the program: Job Corps officials were “heavily influenced by the Moynihan thesis concerning the deterioration of the Negro family. This thesis suggested that, by improving the educational attainment of the Negro boy and enhancing his employability, the cohesiveness of Negro families could be strengthened. It was therefore concluded that the limited resources of the Job Corps should be directed largely to males—the majority of whom were Negroes.” Levitan, “Examination of the War on Poverty,” 7. ↩

-

Administrators specifically targeted cities understood to be sources of violent uprising. A chart in the report labeled “Job Corps goes to the Ghetto” would identify key cities from which they would draw recruits, in light of “last summer’s unrest”—referring to the “race riots” in the summer of 1967. Job Corps Reports (Washington, DC: Office of Economic Opportunity, April 1968), 115. ↩

-

Levitan, “Examination of the War on Poverty,” 14. ↩

-

Manpower 4 no. 2 (February 1973), back cover. ↩

-

On the topic of the “hard-core unemployed,” a Manpower contributor asks, “Do they want to work? What are their occupational aspirations and how much hope do they have of realizing them? What do they look for in a job, and what will motivate them to stay on a job once it is found? These and similar questions often are asked about the hard-core unemployed, and especially about inner-city Negroes who constitute such a disproportionate share of the hard-core unemployed.” R. A. Hudson Rosen, “The Hard Core and the Puritan Ethic,” Manpower 2, no. 1 (January 1970), 29–30. ↩

-

Sar A. Levitan, Garth L. Mangum, and Ray Marshall, “Human Resource Issues for the ’70s,” Manpower 3, no. 11 (November 1971): 2–6. ↩

-

When the building opened in 1914, it was known as the Wardman Court Apartments, named for the prolific real estate developer Harry Wardman. ↩

-

Michael E. Carbine, “Rebuilding the Ghetto from Within,” Manpower 2, no. 6 (June 1970): 7. ↩

-

Rent strikes in 1967 over the state of the building led to a landmark federal lawsuit that would establish the legal basis for tenants to withhold rent from delinquent landlords (Saunders [aka Javins] v. First National Realty Corporation). Strikes also led to the building’s sale to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which would finance the renovation in 1970. ↩

-

Jonathan Berr, “Subsidized Nightmare,” Washington City Paper, July 26, 1996, link. The history of unscrupulous management can be traced to the architect-developers of Clifton Terrace Apartments. Rob Brunner, “What Happens When You Discover Your House Was Designed by a Criminal?” Washingtonian, August 2, 2018, link. ↩

-

DC Historic Preservation Office, “Civil Rights Tour: Housing—Clifton Terrace and Tenant Organizing,” DC Historic Sites, link. See also, Ericka Blount Danois, “Standing Their Ground,” The Crisis; Baltimore 112, no. 3 (May/June 2005): 28–32. ↩

-

“When the ecological surplus is very high, as it was after World War II, productivity revolutions occur and long expansions commence. Naturally, this is not merely a story of appropriation, but also of capitalization and socio-technical innovation. The ecological surplus emerges as new accumulation regimes combine plunder and productivity, joining the enclosure of new geographical frontiers (including subterranean resources) and new scientific-technological revolutions in labor productivity. Great advances in labor productivity, expressing the rising material throughput of an average hour of work, have been possible through great expansions of the ecological surplus.” Jason Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (New York City: Verso, 2015), 102. ↩

-

Morris Mash, “Into the Forest and Out of the Woods,” Manpower vol. 3, no. 2 (February 1971), 13–15. ↩

-

The author describes the camp and work of its residents: “The trim and orderly headquarters of Ecology Satellite Camp, near Breckenridge (sic), KY, is situated on land that was a swamp before Job Corps trainees came in with earthmoving equipment and reclaimed the area. Camp members built access roads and put up fences to complete the site.” Camp Breckinridge, a former army training facility during WII and the Korean War, continues to operate as a Job Corps center. Walter L. Owen, “Infusing Life into Strip-Mined Land,” Worklife, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 1976), 28–29. ↩

-

Job creation leads Joe Biden’s policy platform on climate, based on the framework of the Green New Deal. “The Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice,” link. ↩

-

David Brooks, “Opinion: We Need National Service. Now,” New York Times, May 7, 2020, link. ↩

-

Michael Grace, “Training Alaska Pipeline Workers,” Manpower 7, no. 1 (January 1975): 11–16. ↩

-

Walter Owen, “Solar Grants Spot Training and Jobs,” Worklife 4, no. 1 (January 1979): 16–21. ↩

-

Kenneth Fraser, “Energy War Is Generating Jobs,” Worklife 2, no. 10 (October 1977): 14–20. ↩

-

Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life, 102–103. ↩

-

Françoise Vergès, “Racial Anthropocene,” in Futures of Black Radicalism, eds. Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin (New York City: Verso, 2017). The edited volume is positioned as a continuation of Cedric J. Robinson’s influential work Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, first published in 1983. ↩

-

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a particularly instrumental part of this investment in progress. Title VI directly implicated the Manpower Development and Training Act of 1962 (MDTA) and revised the mission of the Manpower Administration to increase employment under desegregation. Landmark civil rights legislation was, of course, the outcome of years of organized demonstrations, sit-ins, and riots—the very picture of urban disorder that Department of Labor programs attempted to overcome. See “Equality of Opportunity in Manpower Programs: Report of Activity Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” US Department of Labor, Manpower Administration (September 1968). ↩

-

See Howard Gitelman, “Slave Labor in America,” Worklife 1, no. 5 (May 1976): 13–21. ↩

-

Willard Wirtz, “Editor’s Note,” Manpower 1, no. 1 (January 1969): 1. ↩

-

Walter Wood, “Editor’s Note,” Worklife 1, no. 1 (January 1976): 1. ↩

-

In that vein, the issue focused primarily on problems: difficulties finding childcare (“Working Mothers: A World of Problems” contributed by the well-known anthropologist Margaret Mead), discrimination in unemployment insurance provisions (“Less than Equal Protection Under the Law”), and insufficient vocational programs (“Cinderella Doesn't Live Here Anymore”). In “Womanpower,” special issue, Manpower 7, no. 11 (November 1975). ↩

-

Edwin Harris, “In the Manner of Rosie the Riveter,” in “Womanpower,” special issue, Manpower 7, no. 11 (November 1975): 26–29. ↩

-

Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race and Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1983 [1981]), 229. ↩

-

Phyllis Ann Wallace, Black Women in the Labor Force (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1980), 2–4, link. ↩

-

Stephanie Hughes, “Nannies Wanted: Covid-19 Antibodies Preferred,” New York Times, July 13, 2020, link; and Emily Bobrow, “For Nannies, Both a Job and a Family Can Abruptly Disappear,” New York Times, June 29 2020, link. ↩

-

Courtenay Brown and Jordan Flowers, “We Work in an Amazon Warehouse. We Didn’t Sign Up to Be Heroes,” New York Times, May 29, 2020, link. ↩

-

Thomas C. Greening, “Ingredients for ‘Making It’: Study Identifies Common Threads in Lives of Those Who Escape Ghetto,” Manpower 3, no. 8 (August 1971): 3–9. Interestingly, this very perspective is called into question by sociologist and Manpower Administrator Jesse E. Gordon in an earlier issue from 1971. Evaluating the Poverty program and its very definitions of disadvantage, he writes, “The title of the Economic Opportunity Act implies an economic definition of poverty. But the contents imply a psychological definition because the act’s provisions are concerned with ways of changing the behavior of poor people by putting them in work camps, school enrichment programs, and the like. Little in the act prevents institutions from continuing to pay poverty wages for work which everyone agrees somebody has to do. The basic notion of the act is that you change poor people, and they in turn might change institutional structures. In other words, the act assumes that the poor lack certain qualifications for influencing institutions, rather than that institutions lack responsiveness to the poor,” Jesse E. Gordon, “What Shapes Poverty Programs,” Manpower 3, no. 4 (April 1971): 2–8. ↩

-

“Although the program’s most successful participants have been able to earn $40,000 or more in their chosen trades, the Labor Department found that after five years, Job Corps participants on average earned $12,486 a year, barely above the poverty threshold, according to the limited payroll data investigators were able to obtain.” Glenn Thrush, “$1.7 Billion Federal Job Training Program Is ‘Failing the Students,’” New York Times, August, 26, 2018, link. ↩

-

Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “Millions Have Lost Health Insurance in Pandemic-Driven Recession,” New York Times, July 13, 2020, link. ↩

-

The “survival programs” put on by the Black Panthers precede this ongoing work. See the recent essay by Dean Spade, “Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival,” Social Text 38, no.1 (2020): 131–151; and Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↩

-

Li Zhou and Ella Nilsen, “Senate Republicans’ dramatically smaller unemployment insurance proposal, explained,” Vox, July 28, 2020, link. ↩

Gabrielle Printz is a co-founder of a feminist architecture collaborative and a Ph.D. student in architecture history and theory at Yale, where she studies the relationships between architecture, labor, and non/citizenship in the context of global capitalism. In 2009, she did a term of service with AmeriCorps ABLE (AmeriCorps Builds Lives through Education!) at the Women’s Business Center in Buffalo, New York, where she mostly taught new small-business owners how to fill out the forms that would secure the center’s continued federal funding.”