As I make my daily pilgrimage along the shore at Pārua, Whangārei-Terenga-Parāoa, during the COVID-19 lockdown here in Aotearoa, I think about the shifting tides. Tai timu, tai pari.1 Some days, the sea withdraws and scrapes over the shore, the tidal flats pockmarked and laid bare; other times the sea laps against the seawall, the sand swallowed whole, barely visible beneath the surface of water made hazy through constant motion. I wonder about the maramataka,2 which has been elevated in my consciousness as my reality has suddenly narrowed, with lockdown forcing a new, daily intimacy with place. Is it a good day for fishing? For planting? Is it a high-energy or low-energy day? Small observations needed for accurate interpretation require a certain amount of slow attentiveness. I’m not sure what I’m looking for, but I’m beginning to notice things. I think of our grandparents often, growing up on the kāinga3 on the other side of the harbor, and I wonder if their days had a similar quality.

I keep a running list of kai species that grow on the farm and in the surrounding areas, both cultivated and wild. The season shifts, almost imperceptibly, and I might not notice but for the fruits that steadily grow and ripen until, all of a sudden, there is a bounty. There is so much abundance, more than I know what to do with. I start to notice the manu, the bird life. A shrieking flock of kākā4 make ugly noises from their lovely beaks and leave a mess in the persimmon tree. One night, an insect in the tree outside my whare5 keeps me awake for hours. Another night, the full moon shines through the gaps in the blinds and the room is awash with light. I wander outside sleeplessly and lie on the deck in the cool night air, watching as the clouds wash over the brilliant moon.

I te wā o te urutā (in the time of the pandemic)

As the COVID-19 pandemic raged across much of the world, the government in New Zealand responded quickly: the minister of Civil Defense declared a state of emergency, and parliament rapidly passed COVID-19 response legislation. A four-level alert system was introduced on March 21, 2020, and a nationwide lockdown came into effect four days later. For many, it was a slow yawn rather than a grinding halt. The weather was still fine. Many of us were simply grateful to be healthy. Announcers on the radio said “unprecedented” at least twenty times a day and everyone stopped what they were doing at 1:00 pm when the Jacinda and Ashley show came on televisions and radios throughout the nation. For others, existing tensions came to the fore and were exacerbated: families became interred in homes that were already overcrowded, unhealthy, or struggling with mental health, addiction, and intimate partner violence.

A sense of unity pervaded the country and was embedded in all communications and media. We were a team of five million! The criticisms, when voiced, were tame—no one wanted to seem ungrateful when we heard cases were spiking, hospitals were full, and, alarmingly, that bodies were piling up in the streets in other cities across the globe. Everyone praised our center-left government for leading an effective public health response. And when the immediate threat appeared to have passed, everyone quibbled about the economic impact, with the center-right attempting to capitalize on their reputation as a “safe pair of hands” with the economy. After all, 2020 is an election year.

For us as Māori, however, divisions were drawn along different lines. The power imbalance between hapū and the government (as a representative of the Crown) was brought sharply into perspective. The visible use of state power reconfirmed what our iwi of Ngāpuhi have always known and maintained: the colonial government wields immense powers, granted through illegitimately assumed sovereignty, while by comparison the rangatiratanga of our hapū is diminished, impotent.

A series of contrasting images arose:

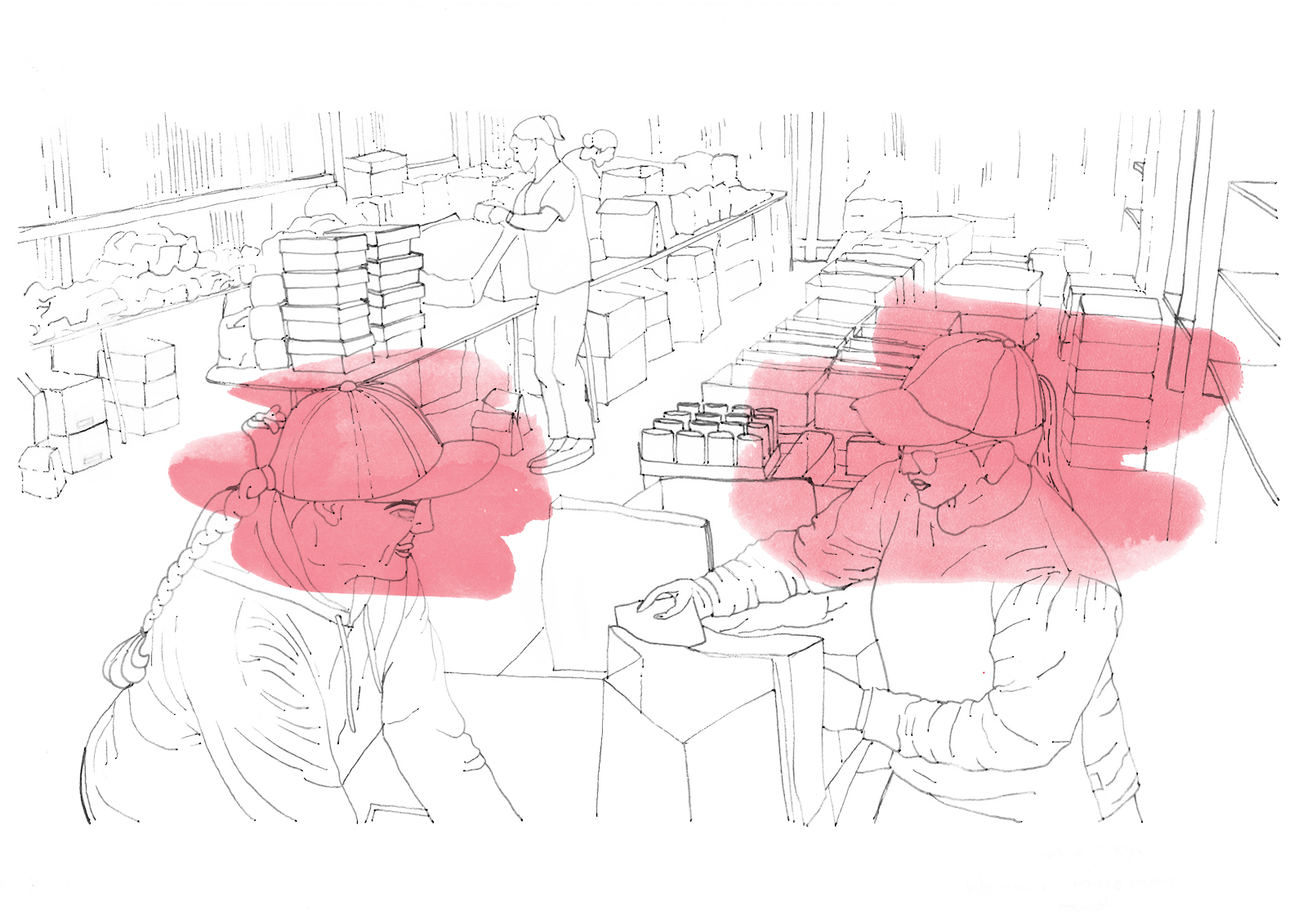

Emergency legislation allowed the government to determine which industries were deemed essential and permitted to operate, and which were legally required to halt operations. With everyone at home but permitted to access grocery stories, distribution and logistics became critical to our collective survival. No shortages were experienced, but panic-buying by consumers created pressure on supply chains and produced uneven availability of some goods. By contrast, iwi and hapū got to work rapidly setting up kai distribution centers, packing food and other essentials and distributing these to those most vulnerable—our kaumātua,6 our families with children, our disabled whanaunga,7 and those with compromised immunity. We knew who our people were and where to find them, but we were reliant on government resources and permission to achieve this. For non-Māori communities, the emergency was a top-down scenario that left citizens to fend for themselves in the remainder of the open market system, while in Māori communities, mutual aid was an immediate and intuitive act underpinned by familial relationships.

The inside of the packing shed on Kākā St. in Whangārei is set up with neat rows of trestle tables, pallets of tinned and packaged kai set out between. Yesterday, they prepared cooked meals at the marae across the road. Last night was meat delivery. Today we’re packing nonperishable dry goods and fruits and vegetables. My pack today is kiwifruit, cabbage, tinned fruit. I cut the cabbage in half for our kaumātua, so it’s easier for them. Outside, a trailer is filled with kiwifruit. As I pack the soft brown rounds into boxes, a boy of around ten helps, telling me stories about his life and asking me rapid-fire questions, then when I’m done, he carries the full box into the shed. Music reverberates. Everyone is busy at their stations, and we steadily work through our list. Each bag gets a label and is sorted into categories. When the van arrives, packers load the back systemically, drawing from the various piles. The driver has a clipboard with the names and addresses of our kaumātua and whānau, which he will tick off as he delivers the packs, one by one.

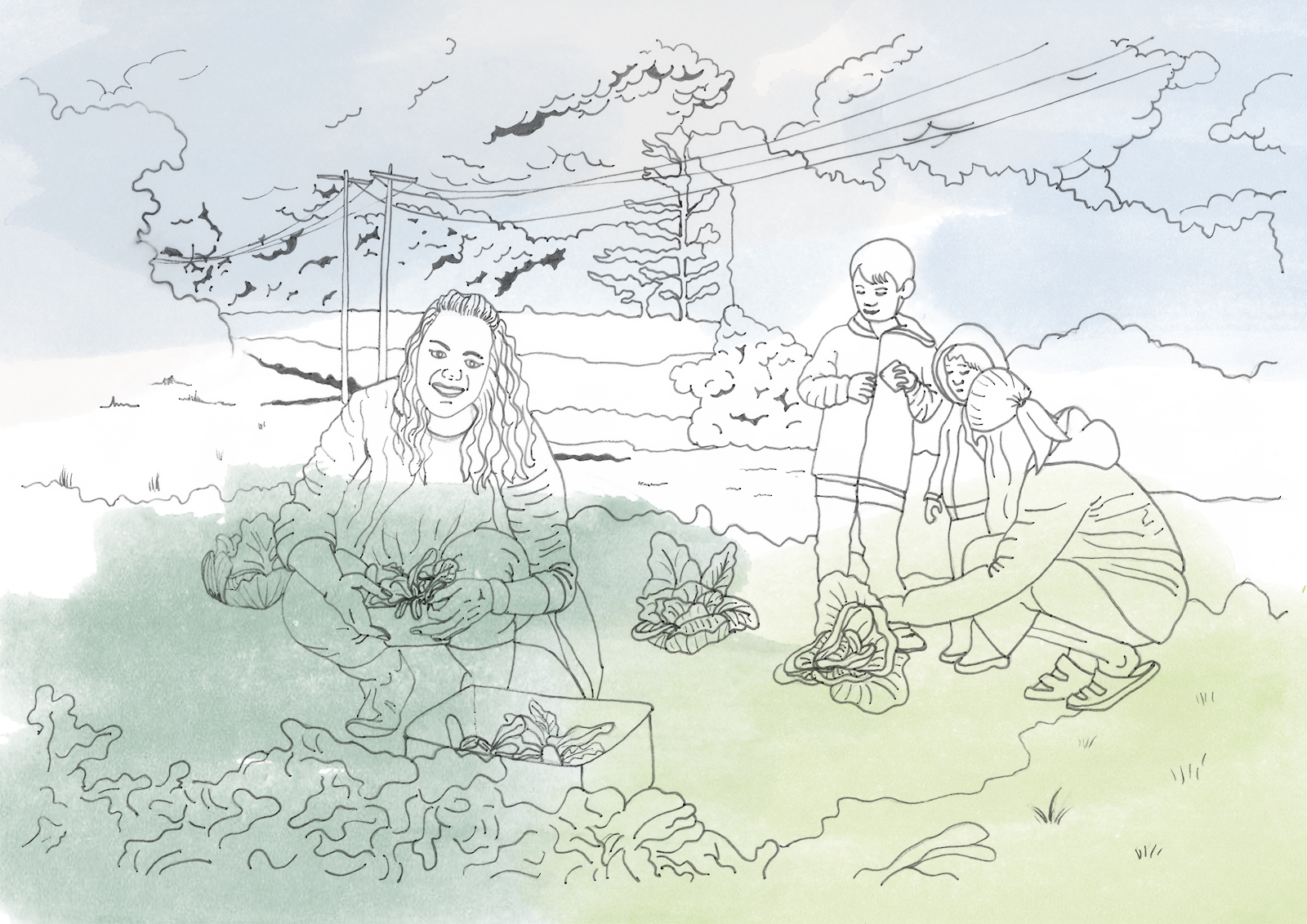

The vulnerability of a centralized food system and the impossibility of social distancing in this environment became evident in the panic buying, the long lines, and the general chaos of many of our larger supermarkets. Elsewhere, whānau who were fortunate enough to have the space, knowledge, and resources to maintain māra8 cultivated the soil and exercised kai sovereignty. The government announced fishing and hunting were banned, and I thought of those whānau in remote areas such as coastal Te Hiku and the forests of Te Urewera, for whom these were likely critical sources of food. I wondered aloud if this might be yet another breach of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.9

I watch Māori Television, where Kaikohe, Matua Hirini Tau, lovingly tends to Te Mahinga Kai o Puhi Kai Ariki. Here, he grows all sorts of potatoes—peruperu, pokohinu, karu parera, karu poti, and rahonika—in rich, dark soil, no fertilizers. Matua Hirini harvests by hand, digging through the topsoil to unearth the potatoes buried there. The potatoes are then shifted to large bins inside the shed; both are made with rough pallet timber. From the bins, they are packed into brown paper bags and delivered to Te Hau Ora o Ngāpuhi, where they are distributed to kaumātua and whānau in need. “Ko te pai o tēnei raru i te ao, whakaako me hoki ki te ao o mua” (the situation in the world is showing us we need to return to our past practices), he tells the reporter who comes to interview him during the lockdown “Kia hoki tātou katoa ki enei momo kai ki te whakatō hou kai, ki te haere tiki ruku kina e runga mahi kia hoki atu ki e ngā ahua o tātou mātua tūpuna o mua” (we all need to return to growing and harvesting our traditional food sources as our ancestors did).10

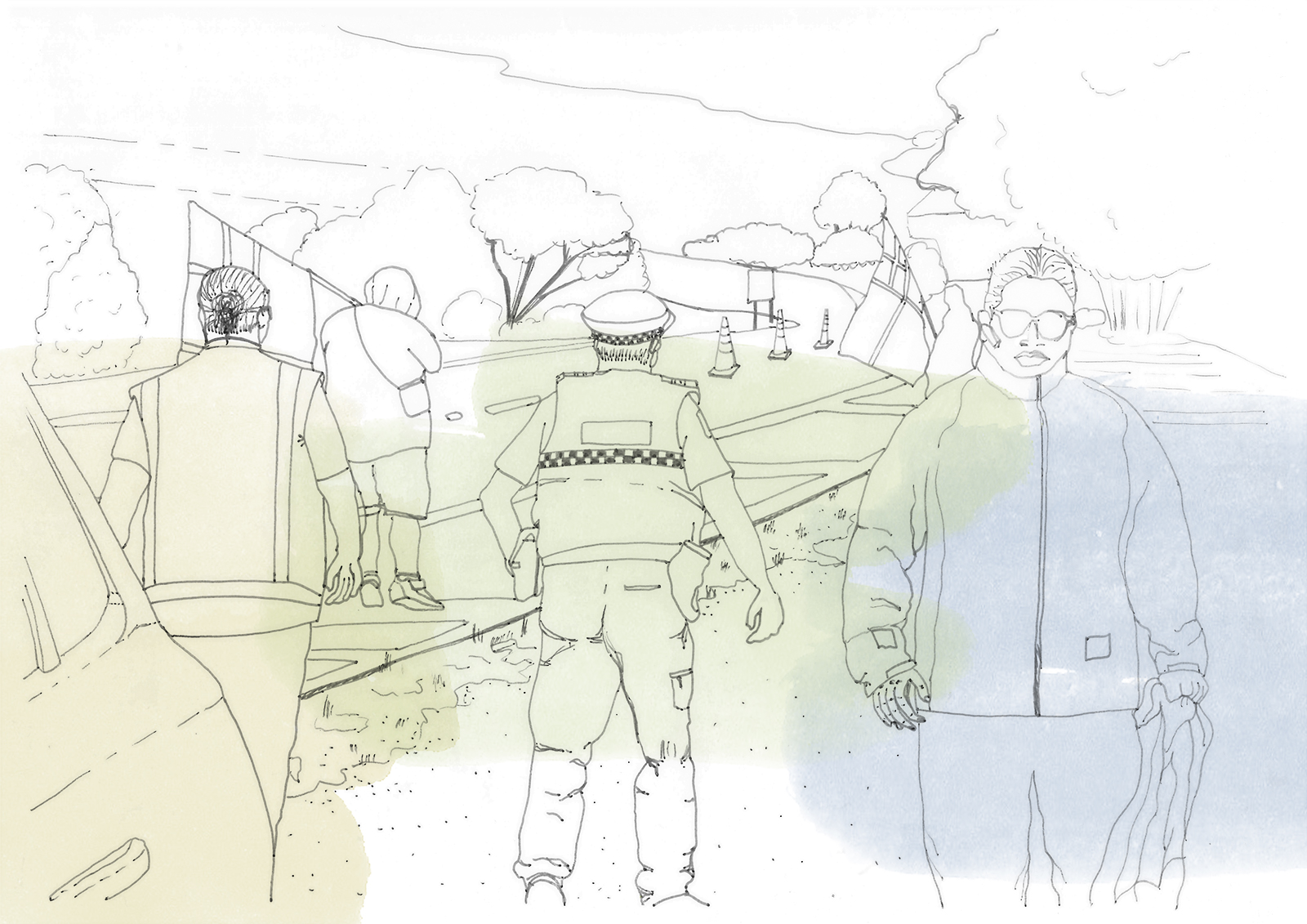

Police were given vast powers by parliament through the enactment of the COVID-19 Public Health Response Act of 2020, which included the ability to perform road checks and deny passage to anyone without a legitimate reason to be on the roads. At the borders of isolated and vulnerable Māori communities, hapū worked diligently to protect their rohe pōtae11 and were routinely criticized for it in the media. The number of COVID-19 cases in Te Tai Rāwhiti remained astonishingly low, in large part due to the efforts of Te Whānau a Apanui. The opposition party publicly questioned the legality of the checkpoints and engaged in a bit of casual race-baiting. Finally, the prime minister stepped in and said it was fine so long as police were also involved. On the taumata,12 everyone talked about the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that devastated communities and filled urupā.13

I read the Northern Advocate. The feature shows Matua Hone Harawira stands by the side of the road on State Highway 1 at Whakapara. A marquee is set up with plastic chairs for those operating the checkpoint.14 Some wear fluorescent safety vests. A few carry United Tribes or Tino Rangatiratanga flags. Those completing the checks wear full-body protective clothing, protective goggles, and face masks. One holds a small medical device in his hands for temperature-checking. When the police do arrive, it’s Far North Area Commander Inspector Riki Whiu, and he asks the group to shift to Waiomio Hill (for road-safety reasons) but doesn’t impede the checkpoint.

In New Zealand, policing is firmly grounded in the colonial past and present. In 1846, the New Zealand Armed Constabulary Force was established to “combat Māori ‘hostiles’ and to keep civil order.”15 The Armed Constabulary later became the New Zealand Police. From 1846 to now, Māori have been the primary victims of police violence.16 Māori are also disproportionately incarcerated, and today, Māori make up 52.3 percent of the prison population, despite being 16.4 percent of the overall population.17 Reports are commissioned ad infinitum to try to figure out why and always, always reach the same conclusion: colonization and racism.18

Reports of near-total economic collapse circulated regularly in the media, with graphs of plummeting lines produced by economists. The banking sector, tourism, international education, and export industries were predicted to take a major hit. Parallels were drawn with the global economic crisis of 2008, and everyone said it would get much, much worse before it got better. Simmering tensions between perpetual insecurity under capitalism and pundits decrying an alternative descent into supposed state-led socialism were brought to the fore by media commentators. Everyone worried incessantly about the economy. Yet, during this time, Māori e-commerce flourished, everyone keen to support and build kāinga-based economies of resilience as soon as we were permitted to do so. “Shop Māori, tautoko, spend Māori,” read the slogan on a popular Māori e-commerce platform.19

On the Tautoko—Te Tai Tokerau Facebook page, the posts proliferate each day. 20 Everyone introduces themselves and their business, pepeha rich with whakapapa from the North—Ngāpuhi and Te Hiku. The feeling is warm, as everyone makes supportive comments. I write a post and get ten messages from whānau interested in planning for papakāinga on their whenua.21 My cousin orders gift wrap and greeting cards in te reo from a māmā and her teenage daughter (the entrepreneur). InnoNative, the local Māori commerce pop-up store and weekend markets are closed to trade because of the lockdown, but Minnie-May Niha, who runs the store, is busy building an e-commerce platform for local Māori vendors. 22

New Zealand’s substandard, poorly configured, and overcrowded housing stock (disproportionately occupied by Māori) exacerbated illnesses for those now forced to occupy their homes twenty-four hours per day, seven days per week.23 Many of those in better circumstances also found that their homes were ill-suited to permanent occupation. We were reminded that many of our homes simply did not provide the essentials required for life. By contrast, those fortunate enough to occupy papakāinga on whenua Māori, which by design focus on the provision of shared spaces and the extension of the home beyond the whare or unit, found their kāinga to be self-contained spaces.

Papakāinga is a contemporary concept based on the traditional kāinga or village, with “papa” referring to Papatūānuku, the ancestral earth mother. 24 It denotes home as a source of sustenance and connection—to the ātua,25 to te taiao,26 to food sources, and to one another. It is deeply rooted in land and history and reciprocal relationships of interconnectedness that span generations. For some, papakāinga represents the repair of a severed connection: the sometimes difficult healing of intergenerational trauma that comes with repatriation.

I listen to a radio interview on RNZ with a prominent New Zealand architect, who has been speaking with her clients about their experiences living and working in the homes she has designed.27 Inner-city professionals, mostly, and their lives feel miles away from the experiences of our communities. I find myself reviewing my recent plans for our papakāinga28 in light of COVID and find that the apartment above the garage is a perfect isolation chamber and that the shower and laundry in the shared garage would be a great place for essential workers to decontaminate before re-entering whānau life. I think about the kāinga at Ōrākei,29 which I have visited a few times, and wonder how they’re faring (I hope, I imagine, well). I overhear someone at the Pārua Bay shops complain about the forty-person “bubble” (an informal term for the household unit to which you are expected to restrict—and exclusively maintain—close contact) at Pataua up the road, and it occurs to me, not for the first time, that our dominant settlement patterns are racist and colonial.

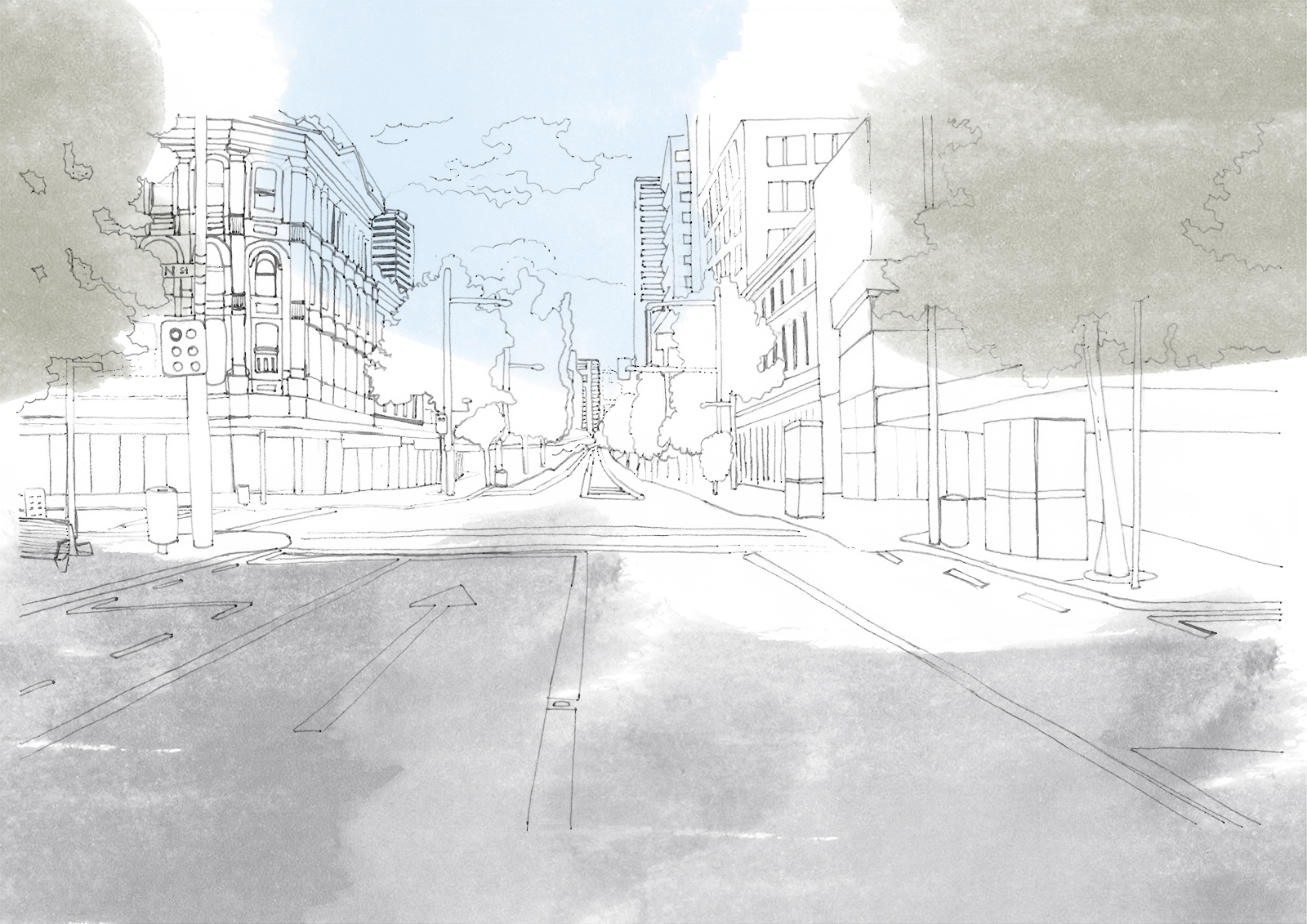

The vast, empty streets in our cities and suburbs reflected an isolating landscape of quarantine, although people soon filled the spaces left by cars. In the process, everyone became more acutely aware of the need for public spaces that are accessible to the places people live. The eerie spaces that suddenly felt alien to non-Māori under quarantine conditions have always felt alien to Māori. The cities are made up of quarried maunga,30 ancestral waterways piped and cemented over, shorelines erased and redrawn, burial grounds desecrated, māhinga kai31 poisoned or uprooted. The streets are named after dead colonizers, and bronze monuments are erected to the same. The markers of our identity, sites of our shared history, and sources of collective sustenance have been degraded and destroyed, sometimes beyond recognition. The city in our reading is a colonial overlay, and rather than merely filling the spaces left by cars, a better opportunity might be to indigenize and decolonize our urban spaces to reimagine a different spatial future after this crisis has passed.

In the New Zealand Herald, photojournalists post early-morning shots of an apocalyptic Auckland.32 The empty streets feel eerie and barren. Not only of cars but of our people. The kāinga kore33 community—most of them Māori—have been shifted, relocated to motel units in compliance with the national lockdown. Meanwhile, in the Women in Urbanism Facebook group, members in Tāmaki Makaurau post photos of the empty streets but also the life and energy that has flourished there in the absence of cars.34 Women ride bicycles to the shops and back without fear of abuse. Families go on bike rides together. Children play in the streets. This feels like a rare and shining moment, but I can’t help but notice that those pictured are mostly (but not exclusively) Pākehā (New Zealander of European settler descent), in leafy tree-lined streets in the inner city. I think of another Auckland, not pictured, one with flat, wide streets and big-box stores surrounded by a sea of parking lots, and wonder how the people there are faring.

Ka whawhai tonu mātou (a struggle without end)35

In Aotearoa, the steady march toward decolonization—which first gained real traction in the 1970s, some 130 years after Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed—has been founded on Māori activism and the shifting demographics and societal values that have followed. The occupation at Takaparawhau, the Māori land march led by Dame Whina Cooper, the establishment of the kōhanga reo,36 kura kaupapa,37 and wharekura38 language revitalization movements, as well as the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal,39 were all significant moments in the mana motuhake Māori40 and tino rangatiratanga41 movements. Cumulatively, these acts pushed the movement toward decolonization in Aotearoa forward. The trajectory of the struggle for Māori political liberation is well known to younger generations, those who have grown up immersed in their culture without shame, and sometimes it’s easy to forget the whakamā,42 the mamae,43 the trauma of assimilation experienced by previous generations.

What do we really mean when we speak of decolonization? At a fundamental level, it’s about the return of land, power, and resources. It’s about who has the power to make laws and enforce them. Our people have said the same thing since the issuance of He Whakaputanga (the Declaration of Independence) in 1835, and in 2014 a landmark Waitangi Tribunal finding confirmed what Ngāpuhi have always known: we never ceded our sovereignty to the British Crown. In 2012–2015, some of our foremost Māori thinkers initiated Matike Mai,44 an independent inquiry to consider the process of constitutional transformation that offers a number of co-governance models and a restructuring of government to reflect our founding documents: He Whakaputanga, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Increasingly, many Pākehā and tauiwi45 have been a part of the journey, engaging positively with the idea of sharing power and moving toward genuine decolonization.

In the built environment, the movement has been much slower. Largely the conditions for this have been created through tribal treaty settlements and through crisis. Two significant examples come to mind. In Tāmaki Makaurau, our largest city, mana whenua have been involved in the shaping of the city due to the amalgamation of seven city and district councils46 and a series of successive treaty settlements.47 In Ōtautahi, the legislation passed for recovery after the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes meaningfully involved Ngāi Tūāhuriri48 as a partner in the rebuilding process.

Despite the COVID crisis being mostly an economic one (as opposed to a physical crisis we experienced during the 2010–11 Canterbury Earthquakes), today’s governmental response has largely focused on building. The COVID-19 Recovery (Fast-Track Consenting) bill was introduced in mid-June 2020 and was passed into law three weeks later. The act includes a worrying lack of protection for hapū/mana whenua interests (those with authority over and responsibility to land) and misses the critical opportunity to include mana whenua in the rebuild. Similarly, the New Zealand Transport Authority has introduced a new placemaking program—Innovating Streets for People—to encourage nonvehicular uses of the street (both as a general program and specifically in response to the need for physical distancing as a result of COVID-19). However, this program—as with numerous others—fails to seriously consider and accommodate hapū and Māori involvement. The overall response has been disappointing, lacking in imagination. Measures like the ones above fail to consider the possibilities that might be presented if hapū rangatiratanga were a guiding factor in the development of legislation and government response.

As New Zealand becomes increasingly urbanized, we as hapū have struggled to reconcile this vision of our kāinga. With the rapid pace of urbanization and the increasing subdivision and development of land, there appears to be a growing impossibility of land’s return to our administration. Despite the increasing role of mana whenua in development, very little land has been returned to hapū governance, and the proportion of whenua Māori remains stubbornly low at around 5.33 percent49 of the total landmass.50 The increasing indigenization of spaces and buildings in our cities is a cause for hope and celebration with our identities inscribed across buildings and landscapes. Yet for all that this achieves, it is still not return of land, or of people to land. Yet our hapū have remained clear and steadfast. We want our land and sovereignty back. Even so, the line between decolonization and indigenization isn’t always clear-cut, and the impact of every movement toward a shift in power is palpable.

Through the experiences of COVID, the seemingly permanent colonial overlay has been fractured and laid bare. I wonder if the sense of alienation and mamae that Māori feel constantly is, for the first time, becoming apparent to our treaty partners (including all who are not tangata whenua who reside in these lands, given the rights of citizenship and residency through Te Tiriti), although perhaps these parallels remain apparent to us alone. This seems like a ripple in the space-time continuum, something straight out of science fiction, and I’m not sure what I hope will happen—perhaps that this opportunity for genuine understanding and impactful change won’t be squandered. Amid a disappointing national response, I wonder, what might a post-COVID recovery look like if our government seriously considered the relationship with us under Te Tiriti o Waitangi and committed to sharing power as genuine partners in the rebuild? What would it mean if central and local government willingly worked with us as equals?

Ka mua, ka muri (looking backward into the future)

When I imagine a different spatial future, I imagine a landscape that is no longer cut into pieces, stolen, and then sold and sold again, at ever-escalating prices. The system of private property ownership is a cornerstone of the New Zealand economy and has remained stubbornly robust despite the pandemic. Dismantling this system feels like a near-insurmountable challenge, with the treaty settlement process returning only a tiny fraction of what was taken.

As part of the constitutional transformation process, the kawana51 has returned responsibility for all land within our hapū rohe52 to hapū and put an end to land sales. As part of the decentralization of government, no Crown land can be sold privately and must instead be offered back to hapū if it is no longer needed. Private landowners have started offering land back to hapū in exchange for homes within newly developed villages. All land is held collectively by hapū, and individual whanau—hapū Māori and tauiwi—are granted the rights and responsibilities of occupation within new, healthy housing at the center of communities.

I imagine our quarried maunga, our filled-in awa53 and moana54 being whole again. I imagine thriving biodiversity and healthy waterways, no longer polluted. Currently, the resource management system provides reasonable protections, and our environmental goals feel achievable—if a somewhat rocky journey, at times—neatly converging with the interests and priorities of a large portion of the Pākehā majority, although still heavily opposed by some.

I walk along the stream that winds its way through our city. The pathway is new, and parts of the stream have recently been daylit (after being piped and cemented over by municipal authorities in previous decades) and rediverted to follow the original path. I find a spot that’s cool and shady under a grove of kahikatea55 by the stream bank. Further uphill, I spy a kukupa56 nestled among the leaves and orange berries of a karaka tree, healthy and fat. I sit on the bank and unwrap my sandwich of rēwana bread57 and smoked tuna.58 Further upstream, my cousin tells me, is an īnanga59 spawning site, where īnanga have been spotted for the first time in years.

I imagine our physical markers of identity, our maunga, awa, pā, and kāinga being within our collective control. A few years back, my whanaunanga bought back Hurupaki, the ancestral maunga.60 Even though the alienation should never have happened, even though this whanaunga should not have had to use his personal resources to buy it back, when we ascend Hurupaki, it feels intensely healing and radically decolonial.

We ascend the maunga before dawn. In the still hours of a cold winter morning, our breath fogs the air. We wear thick winter jackets, our gloved hands thrust into pockets. As we walk, we pass through no fences, and no one attempts to stop us. When we reach the summit, the horizon seems to extend into forever, Matariki61 just visible, peering over the edge. We whisper in awed and hushed tones, and one of us says a karakia to usher in the new year that our kaumātua taught us. The sky slowly lightens, in shades of orange and pink, until the ocean shines a brilliant blue.

From our maunga I look over to where I know our rua kōiwi62 are. We know not to go there; the place is tapu.63 A Pākehā farmer returned the land to our hapū when he died. The pūriri64 grove was returned at the same time, and both Māori and Pākeha know to avoid these places. Since then, a whānau in our hapū has been lovingly caring for our dead and slowly reintroducing our burial practices. We recently reinterred the bones of some of our tūpuna,65 the first time anyone has been laid to rest there in hundreds of years.

I imagine sustained access to and maintenance of our māra and māhinga kai, our food sources, and to our pā harakeke and other cultural resources. I am reminded of the Crown legislation has actively prevented us from doing so. In 1907, the Whangārei Harbour Act66 stole all of our lands and fishing ground below the high-tide watermark. In 2011, then-MP Tariana Turia crossed the floor of the debating chamber in parliament67 to oppose the Foreshore and Seabed Act.68 Today, the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act Inquiry69 is underway in the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate Crown breaches of the treaty in relation to customary marine and coastal area rights. Our hapū are forced to navigate a barrage of new laws and planning ordinances with each generation as we seek to exercise kaitiakitanga, our inherited cultural responsibilities of stewardship.

As I step onto the rocky beach, I see my uncle fixing a kupenga, a fishing net, and I wave to him. I see my nephew and my uncle have set up camp for a few days to catch hīhī70 and aua.71 The area below the high-tide mark has been returned to our hapū, and with it the reclaimed land on the edge of the city. Responsibility for the harbor has been returned to hapū, and the oil refinery and factories along the harbor’s edge have long since closed down. I untie my waka72 from the pou,73 and drag it down to the beach. As I walk into the water, the cold stings my feet and sand swishes around my toes. I put my kete74 in the front of the waka, and I can still feel the warmth of the freshly baked rēwana bread and smoked fish. I push off in the direction of the next kāinga across the harbor, the lights still twinkling in the early-morning sea mist.

I imagine thriving kāinga, our villages, filled with our people and brimming with our culture and our language; our people living in whare and communities that are healthy and that reflect who we are. This vision sustains me on the long journey of returning to the whenua. For a decade I have been working toward this goal with my whānau: to return to our land after two generations of absence. The stories we tell ourselves about our shared past and our collective future bind us together and provide the sustenance to stay the course on this journey. Still, the structural barriers are numerous: our restrictive planning system, limited access to finance, aspects of Māori land law (the restrictions and limitations of present—but also the legacy of past—legislation). Te mea, te mea (and so on and so forth).

I stand on the deck and look out at the kāinga, a steaming cup of coffee in hand. My mother’s house is to the left of mine, and my sister’s is farther down the hill, on the other side of the māra. My uncle, our kaumātua, lives in the granny flat behind. From this vantage point, I can see my irāmutu75 helping her nanny in the garden. She’s still at kōhanga reo; she hasn’t started kura yet, but she knows all of the different types of hua whenua76 that grow in the garden, including the various kinds of kūmara77 and rīwai,78 as well as the hua rākau79 that grow and are gathered in the forest. I overhear her kōrero i te reo; she’s telling her kuia80 about the wētā81 and the pūngāwerewere82 she saw in the forest yesterday. I call out to her, e kōtiro, haere mai ki te parakuihi; it’s time for breakfast.

When I imagine a different spatial future after the pandemic, I imagine decolonization, hapū rangatiratanga, mana motuhake Māori.

-

The tide cycle, from high tide to low tide. ↩

-

Māori lunar calendar. ↩

-

Village. ↩

-

A type of native parrot. ↩

-

House, dwelling. ↩

-

Elders. ↩

-

Relatives. ↩

-

Food gardens. ↩

-

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is an agreement signed by Māori rangatira (leaders) and representatives of the British Crown in 1840 and is viewed by many as New Zealand’s unofficial constitution. Te Tiriti guaranteed a number of rights for Māori hapū (subtribes) and British settlers (and others who settled after this agreement). The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 as a permanent commission of inquiry investigating breaches of Te Tiriti through Crown acts or omissions. ↩

-

Dean Nathan, “Garden for Elderly and Whānau in Need Proving its Worth,” Te Ao Māori News, March 29, 2020, link. ↩

-

Tribal autonomous region. ↩

-

Orator’s bench on the marae and seat of decision-making. ↩

-

Burial grounds. ↩

-

Peter de Graaf, “COVID-19 Coronavirus: Hone Harawira to Lockdown Far North with Checkpoints,” Northern Advocate, March 25, 2020, link. ↩

-

Elizabeth and Harry Orsman, eds., The New Zealand Dictionary (Auckland, NZ: New House Publishers, 1995), 5. ↩

-

Emilie Rākete, “The Whakapapa of Police Violence,” The Spinoff, June 4, 2020, link. ↩

-

Ara Poutama Aotearoa Department of Corrections, Prison Facts and Statistics—June 2020, link; “New Zealand’s Population Nears 5.1 Million,” Stats NZ, September 23, 2020, link; “National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2020,” Stats NZ, June 30, 2020, link. ↩

-

Thomas Manch, “‘A Vessel of Tears’: Grief and Colonialism at the Heart of Criminal Justice Experience, Report Says,” Stuff, June 9, 2019, link. ↩

-

InnoNative Economy, Tautoko—Te Tai Tokerau, Facebook group, link. ↩

-

Land. ↩

-

“More than 2 in 5 Māori and Pacific People Live in a Damp House—Corrected,” Stats NZ, May 19, 2020, link. ↩

-

For examples of contemporary papakāinga, see Jade Kake, Indigenous Urbanism [podcast], 2018, link. ↩

-

Sometimes translated as “gods” but more accurately interpreted as “ancestor with continuing influence.” ↩

-

The natural environment. ↩

-

“Architect Judi Keith-Brown: the Future of NZ Homes, RNZ Saturday Morning, May 30, 2020, link. ↩

-

Contemporary village on ancestral land. ↩

-

Bill McKay, “Whānau-Focused: Kāinga Tuatahi Housing,” ArchitectureNOW, November 13, 2018, link. ↩

-

Mountains. ↩

-

Food gathering areas. ↩

-

“Covid 19 Coronavirus: Photos Show Empty Spaces in NZ and Around the World,” NZ Herald, April 4, 2020, link. ↩

-

Houseless. ↩

-

Women in Urbanism, Women in Urbanism Aotearoa, Facebook, link. ↩

-

Ranginui Walker referred to the Māori movement for political self-determination as a “struggle without end.” Ranginui Walker, Ka Whawhai Tonu Mātou: Struggle Without End (Auckland, NZ: Penguin, 1990). ↩

-

Māori language preschool. ↩

-

Māori language primary school. ↩

-

Māori language secondary school. ↩

-

A permanent commission of inquiry into Crown breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. ↩

-

Māori independence. ↩

-

Self-determination. ↩

-

Shame. ↩

-

Pain. ↩

-

Mātike Mai Aotearoa, The Report of Mātike Mai Aotearoa: The Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation (Auckland: Mātike Mai Aotearoa, 2016), link. ↩

-

Non-Māori. ↩

-

Through the Local Government [Auckland Council] Act 2009. ↩

-

Passed into law through bespoke treaty settlement legislation. ↩

-

A hapū o Ngāi Tahu, a Te Wai Pounamu (South Island) iwi that achieved settlement in 1998. ↩

-

Te Kooti Whenua Māori: Māori Land Court, Māori Land Update—Ngā Āhuatanga o te whenua June 2019, Ministry of Justice, June 2019, link. ↩

-

The World Bank, Land area (sq. km), New Zealand (2018), link. ↩

-

Settler government. ↩

-

Territory. ↩

-

Rivers. ↩

-

Harbors. ↩

-

Native podocarp tree. ↩

-

Native wood pigeon. ↩

-

Bread made with potato yeast. ↩

-

Eel. ↩

-

Whitebait. ↩

-

Jeremy Rose, “Huruiki—The Return of a Mountain,” RNZ Te Ahi Kaa, December 13, 2015, link. ↩

-

Pleiades. ↩

-

Burial caves. ↩

-

Restricted. ↩

-

Tree associated with funerary and burial rites. ↩

-

Ancestors. ↩

-

Helen Leahy, Crossing the Floor: the Story of Tariana Turia, Wellington, NZ: Huia, 2015. ↩

-

The Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act Inquiry, Waitangi Tribunal, May 14, 2018, link. ↩

-

Fish. ↩

-

Herrings. ↩

-

Canoe. ↩

-

Pole. ↩

-

Woven bag. ↩

-

Niece/nephew. ↩

-

Vegetables. ↩

-

Sweet potato. ↩

-

Potato. ↩

-

Fruits. ↩

-

Grandmother, female elder. ↩

-

A type of large insect found in trees and caves. ↩

-

Spider. ↩

Jade Kake (Ngāpuhi, Te Arawa, Te Whakatōhea) is a designer and writer. She leads a small practice, Matakohe, which supports Māori communities and organizations to develop marae and papakāinga projects and to express their cultural values and narratives within the public realm through urban design, landscape, and architecture. She lives and works in Whangārei.