Yes, I contemplate the sea, what else is there to do? To dive in… To come close to the sea, to look into her until nothing else is visible, and finally, for a fraction of a second, to finish in the gaze of this shifting mass that has neither beginning nor end… to look at the sea is to become what one is.1

The 1991 film The Suspended Step of the Stork, by Theo Angelopoulos (1935–2012), begins with an uncanny, recurrent image of the Mediterranean Sea.2 The air is misty. Two helicopters circle above the sea, diving down and flying up, while two rescue boats wait until a break in the violent undulation of the waves allows them the opportunity to approach the event. There is a soft light; it might be the early morning sun. The barely visible contours of a mountainous coast in the background complete and complicate the scene by suggesting a possible location, but the exact coordinates are unknown. Is it near one of the islands between Turkey’s west and Greece’s east, where one can hardly pinpoint the boundaries between land and sea? Or is this one of those port cities that mark the Mediterranean as a landscape of change and exchange? More immediately, perhaps, what is taking place right now in this water?

Angelopoulos eases his disoriented viewers into the event by gradually moving the camera closer to the scene, slowly identifying the floating silhouettes at the center of the frame. The camera captures the situation without cutting away and clarifies the field of vision despite the incessant approach and retreat of security helicopters and coast guard vehicles. Now viewers are close enough in time and space to see. A voice-over accompanies the movement of the camera, reporting that we are looking at the “bodies of the Asian stowaways who chose to die somewhere around the port town of Piraeus, by jumping into the water from the deck of the Greek ship, Oceanic Bird, which was taking them back home after the Greek authorities refused to grant them political asylum.”3

The voice-over belongs to one of the main characters in the film, Alexander, a journalist who recalls this scene on his way to a northern border town in Greece to write a story about refugees living there. The Mediterranean thus emerges in The Suspended Step as a site framed by Alexander’s memory, preoccupied by a single question, “How does one decide to leave, why, and to where?”4

This happens to be the first and last moment that the audience witnesses the Mediterranean in the film. However, the suicide of the displaced lurks beneath the surface of its 136 minutes, which trace “the lost gazes” of those who inhabit the margins of a capitalist world order, those who either decide or are forced to leave but never arrive where they intend to go.5 Following the displaced through and beyond the tracks of a fictive suicide, Angelopoulos strips the viewers’ gaze of its indifference to Mediterranean geography. In so doing, he creates a mirror-image in the rest of the film, one that reflects the faces of the displaced who look the camera straight in the eye. We, the audience, on the other side of the screen, are exposed as witnesses. We are responsible for discerning meaning from the enormous silence captured by the camera in the aftermath of the suicide, while Alexander, appalled by his memory, guides us toward seeing violence through the conditions of refuge. In other words, the camera invites the audience to take up the challenge of actively engaging with the Mediterranean beyond the Mediterranean.

Exploring the possibilities peculiar to the aesthetics and techniques of cinematic form, in what follows I dwell on the spatiality of refuge to reflect on contemporary notions of exile, homelessness, and loss. Drifting away from the archetypal images of “civilization” and “democracy”—be they of “the city” or “the agora,” as Eurocentric architectural histories tend to canonize the tectonics of the Mediterranean—I aim to build a conversation about another sea: the wreckage of colonial and imperialist imaginaries of war.

“How many borders must one cross before arriving home?”6

Aesthetic practice in Angelopoulos’s cinema manifests a profound critique of war, designed to induce a meditative narrative rather than a cathartic one. Artistic form here provides a peaceful refuge for poetic ruminations about what the lack of peace entails. Every sound, every look, every texture, and every color in this cinematographic sanctuary reverberates with pain. As the ghost of an exile in the film puts it gently, “everything [one] touches… hurts deep inside.”7

Embedded temporalities in the moving image take the form of human landscapes—sedimented as stories of witnessing, surviving, or escaping war. Escape, however, does not mean a way out. Every political subjectivity, in one way or another, embodies certain predispositions toward war—whether loss, violence, nostalgia, melancholia, or apathy. Thus the Mediterranean in The Suspended Step gets lost in a “protracted war,” to recall the conceptualization of artist and theorist Walid Sadek. Sadek does not simply diagnose an irresolvable condition embedded in “a morbid past” that keeps haunting the present but instead imagines the emergence of a new form of sociality from the temporal siege of protracted war(s). He calls for a reconsideration of “the fatalism of the protracted now” with the hope that a living, collective body might emerge from an endless moment of grief bundled around dead bodies—a social and political collectivity that will not necessarily negate its very condition of existence, “the lingering with the corpse.” One could argue, drawing on Sadek’s proposition, that from the absence of the sea emerges “another modality of waiting,” an unending “now” of grief, conditioned by continuing wars.8

The film is named after one such temporal image, the suspended step of a stork.9 A Greek colonel, who guides Alexander during his journey into the complex ecology of borderlands, performs this image by standing on one leg like a stork over the borderline separating Greece from the north. At the same time, he faces the other side of the border as if he is about to cross the line and warns Alexander of a seemingly simple yet lifesaving fact: “If I take one more step, I’m ‘elsewhere’ or I die.”10 This association between the suspended step of a stork and the suspended step of a human on a borderline gestures at the possibility of a temporal transition distinctive to humans. Transition from where one stands, or rather from one’s standpoint to “elsewhere,” or to “death,” refers to a painstaking journey woven across and beyond the borderlands rather than a momentary act of crossing the borderline.

Each of Angelopoulos’s shots contributes to an index, a dynamic frame of reference that clarifies war as an ongoing process of border-making. The film takes place in 1991, at the moment Yugoslavia was fracturing into a space where the only possibility for many to survive would be to escape its borders. The film expresses the conditions of possibility for such survival in the words of a refugee from the north (Albania or former Yugoslavia) who embraces Alexander’s visit and says: “Our home is your home! Home! We crossed the border but we’re still here. How many borders must we cross before we are home?”11

Here in this statement refers to Florina, the frontier town at the intersection of Greece and what are now the borderlands of Albania and North Macedonia; home in this case corresponds to a ramshackle dwelling at a zone abandoned by the locals to the refugees. Alexander discovers that the locals, in fact, call this town “the waiting room” because the refugees inhabit this place in transit for some time before or after moving toward new lives and livelihoods. But the film indicates that the refugees might as well settle in this waiting room if there is, in fact, no way out, no new place to move to. Then, the waiting becomes permanent, as the Greek colonel implies when introducing the notion to Alexander: “They’re all waiting for their papers to go ‘elsewhere,’ and this ‘elsewhere’ has taken on a strange meaning… mythical.”12

The land thus becomes the sea, for the journey toward “freedom” irreversibly distorts the temporality of waiting, and “home” turns out to be a mythical voyage with an unknown itinerary. In The Suspended Step, both Alexander and the ghost of an exile undertake a Homeric journey. And perhaps all the inhabitants of Florina, or the figure of “the refugee” more broadly, repeat the journey by playing into the classic canon while at the same time “revising and reconsidering” it substantially.13 Fugitives of the 1990s from a Mediterranean then permeated with ongoing wars set sail for waiting rooms like Florina. The film follows not only those escaping the brutality of upcoming wars in the post-Yugoslavian context but also women, men, and children of all ages who could find a way out of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Florina brings together these protagonists of another sea. For instance, a man from Iran describes the intricacies of his journey as follows:

I could never imagine that I’d ever want the moon to die. Yet I remember at that moment I wished the moon would die. I didn’t want it to show itself for its light would betray me, and they would catch me. Maybe it was the fear of death, maybe because the road behind me was synonymous with the death [that] awaited me if I didn’t manage to cross.14

Another man that the film identifies as a Kurd alludes to the reason for the mass Kurdish exodus from the margins of a fractured Kurdistan in the late 1980s, and says, “Because of chemical weapons, we were forced to leave the country; when we reached the Greek-Turkish border on the river, we couldn’t go any further.”15

These two accounts refer to yet another tragic moment in the Iran-Iraq war, marked by the death of thousands when Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Army attacked the Iraqi Kurdish city of Halabja with chemical weapons.16 Such witness accounts—scripted but based on real events—help the audience make sense of the Mediterranean geography “as above all, making war,” in the words of critical geographer Yves Lacoste.17 Lacoste’s statement unsettles conventional public perceptions of geography as a scientific form of institutionalized knowledge and instead posits a new understanding of geography as an evolving technology of knowledge production, inextricably linked to the art of war-making.

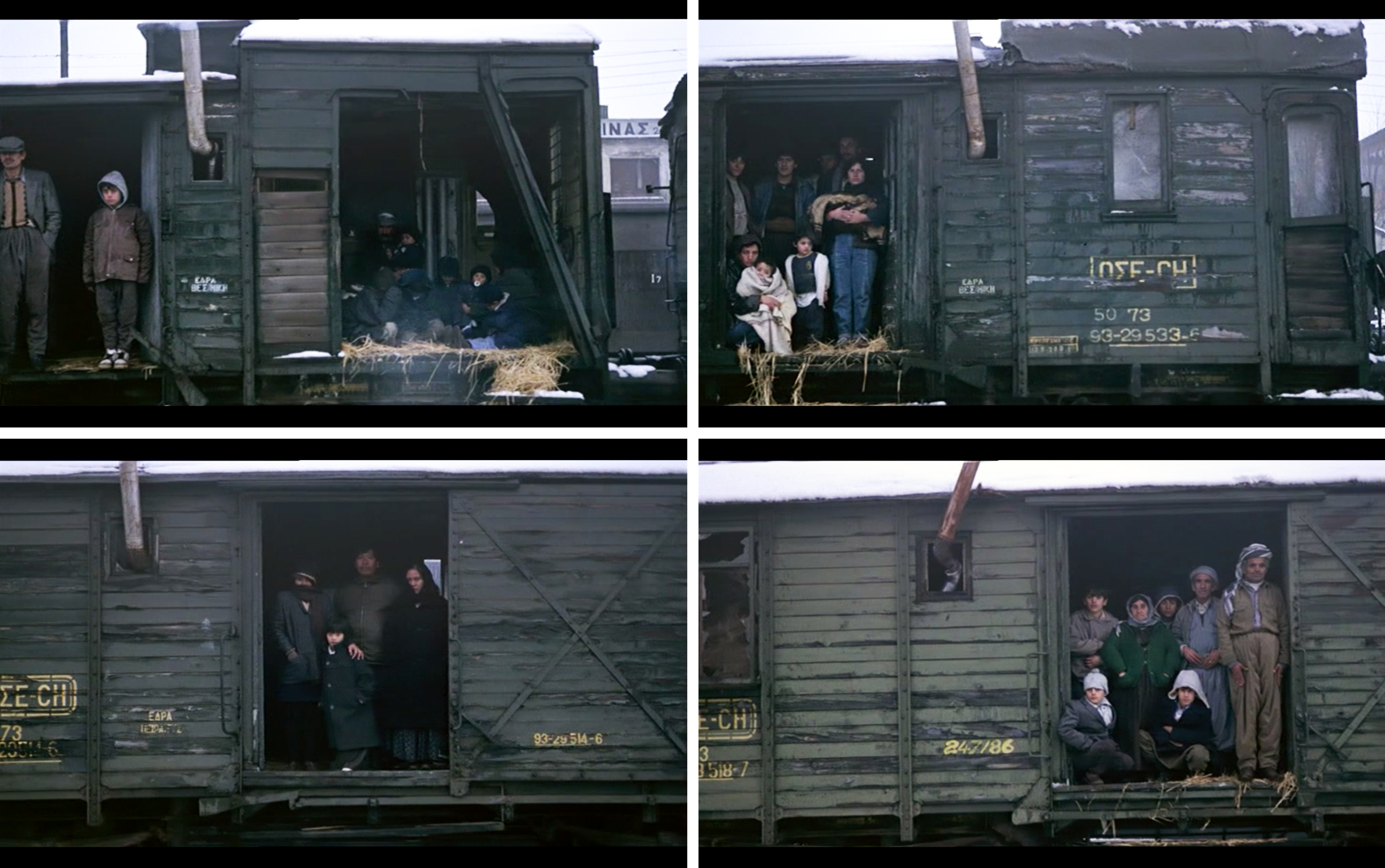

From this perspective, the infrastructures of the Mediterranean geography do not transport people from a point of violence to a point of peace. The practices of crossing borders instead beget borderlands: lands rendered by other, less visible borders. That is why the most iconic scenes in this film take place on railways. A long shot capturing the souls inhabiting the disused timber wagons of a post-industrial Europe sets the stage for the next long shot, at the same location, investigating the alleged murder of a refugee by the members of the refugee community. The Greek colonel takes Alexander to the scene of the crime, and describes what he calls “chaos”: “They cross the border to be free, and end by setting up a new border here… And then they never talk, the law of silence. Nobody knows if it’s between Christians and Muslims, or Kurds and Turks, or revolutionaries and ‘opportunists,’ as they call them here.”18

In this provocative scene, the camera moves through motionless wagons, capturing poignant looks on people’s faces while the stories of Kurdish refugees continue to occupy the center of frame. For this political subjectivity, whose everyday life in the 1980s and 1990s was constituted by novel technologies of genocide, the geography means fighting back against centuries of border-making practices at the intersecting territories of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Notwithstanding the continuing fight, it is important to note that the borderland politics in this particular case have been choked to death by both state violence and tribal, ethnic, and religious feuds. By partitioning the post-Ottoman space into the neocolonial territories of nation-states, European imperialism did not simply erect borders drawn by military strategists but rather engendered generations of bodies marked by the sectarian politics of the borderlands. Angelopoulos painfully demonstrates that wherever the refugees go in this geography of endless border-making, they are inevitably tied to the borderlands intrinsic to their bodies—borderlands that they relentlessly desire to dismantle.

A politician in the film refers to the borderlands dilemma as “the despair at the end of the century,” right before he himself abruptly disappears into a self-imposed exile by leaving a riddle for the audience to reflect on: “There are times one has to be silent in order to be able to hear the music behind the sound of the rain.”19 The law of silence overtakes the scene and the audience can hear the loss of the world despite the clamor of a century. Silence renders audible not the voices but the faces of the refugees, which seem to say: Disused wagons of a crumbling Europe could carry us nowhere other than toward a majestic collapse; liberté, égalité, fraternité are no more, as they never existed for all.

This is a politics in crisis, trapped between despair and silence.

“How will this journey end?”20

In one of those abandoned wagons lives the ghost of an exile. A refugee kid asks him the fundamental question of how their journey will end. Silence fills the air once again; neither know the answer. The question is posed, in this case, on behalf of “the broken lives of the abandoned children,” as Angelopoulos described them, the victims of the Balkan War.21 One can almost imagine a Mediterranean that rescues them from the confining politics of frontiers: With the seamless, smooth, indivisible, transparent, and hence liberating nature of the sea embracing its children. With the serpentine order of the Mediterranean coming forth to end all of these wars, bringing the beauty after the storm, uniting water and sky, and reminding all of the possibility for change, as in an astute verse formulated by the poet and artist Etel Adnan:

Geometries undefined. Not an apology for perfection, nor an alternative notion of form, but the fusion of sounds with light, there, where anything goes wild within change’s archaic identity.22

Angelopoulos’s cinema insists on showing the sea’s materiality as one of constant change, yet one is always already interrupted with the imageries of borderlands. This encourages the audience to see through the sea a medium of struggle for rethinking the question of what it means to be a human.23 To be more precise, through the sea unfolds the very question of “What are we?” in a way that the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn framed this question as a matter of seeing and representing.24 What kind of a self-reflection do we humans see in the sea? Or, to further Angelopoulos’s inquiry by following Kohn’s framework, what does the sea think of us?

The answer in The Suspended Step comes through the visuality of a sea inscribed with the suicide of the displaced.25 From the perspective of the displaced, as seen in this specific representation of the Mediterranean, the struggle to define what it means to be a human includes the act of choosing to die at sea instead of surviving, dehumanized, on land. The suicide under arrest signifies a transgressive act in that it breaks the law of silence and paradoxically defies being killed by the state. The visuality of the suicide poses a series of ethical questions that demands consideration when seeing every new instantiation of the same image on the news reports showing the bodies wash up on the shores of the Mediterranean: What are we, when faced with the death of the displaced? Who are we in this particular moment that brings the fluidity of the Mediterranean to a standstill? Does this image allow us to confront the limits of a nihilistic view of human existence, a view that puts a strain on all moral values and ethical principles? 26 Or does it simply reinforce that view?

Situating the displaced at the center of the Mediterranean, a geography itself a border now, asserts an aesthetic proposition that the auteur diligently curates in response to the question of “what is politics”? 27 Moreover, revealing the death of the displaced in the act of suicide, Angelopoulos’s Mediterranean makes the audience witness an arguably unique form of resistance that undoes state-sanctioned violence. In doing so, the film commits to crafting a new ethics and politics of witnessing. Viewers are called on not only to observe their appearances in the mirror image that Angelopoulos presents for them but also to watch an extremely unsettling narrative that likely pains them deeply. The viewers become involved in the narrative, for the act of witnessing wounds irrecoverably.

Angelopoulos’s Mediterranean further asserts that there is more to the definitions of “human-ness” than the obvious distinction between “the European-human” and “its others,” as the feminist geographer Kathryn Yusoff has theorized: that the human-ness of the “others” are also split into myriad hierarchies drawn by a politics of despair.28 In other words, while some migrants “make it” to the waiting rooms, “the others” inevitably face the conditions of displacement yet again. The archaic nature of the Mediterranean as a mutating form of resistance turns out to be a deception, interwoven with voyages made by Oceanic Bird(s), carrying some stowaways to the mercy of the sea and leaving others to the law of the land.

The sea thus becomes the land, as the impossibility of fleeing an exclusionary western humanism transforms the spatiality of refuge irreversibly. The Mediterranean in The Suspended Step embodies a solid territory, representing the existential predicament of the exiles who escape the fear of permanent stasis by following a desire for revolution only to find themselves in the already constituted sea routes of a fraudulent humanitarianism. What the mainstream media has often framed as “Europe’s biggest humanitarian crisis since WWII” is not a humanitarian crisis.29 Nor is it unique to the temporalities of the World Wars and their legacies. The crisis that we are all in right now is historically as deep as the Mediterranean and geographically as global as the technologies of sea voyage that once rendered the earth an object of colonial discovery.

Violent displacements have mapped the history of a continuing crisis that must be understood within the spatiality of refuge.30 The distinctiveness of the current predicament, however, is about the expanding scale of the borderlands. There is nowhere left to escape to, even as everywhere becomes someplace to escape from. If we take one more step, we are elsewhere, or we die.

What emerges from such agony for those still determined to unbuild borders and build instead an ethical stance toward a politically engaged architectural philosophy is a way of seeing through the sea a panorama of refuge entwined with a psyche that is “never feeling at home.”31 This is how Angelopoulos portrayed his own existential condition before he was hit and killed by a motorcycle in 2012 while shooting his last film, The Other Sea, near Piraeus—the port town that ironically sets the stage for the suicide that opens The Suspended Step. And the step remains incomplete. As witnesses to Angelopoulos’s Mediterranean, we should not only admit but also embrace the fact that none of us will ever feel at home again.

Homecoming is no more; exile is permanent.

In the absence of closure, the Mediterranean calls for dismantling the narratives of humanitarian crisis by historicizing emergent topographies of displacement, topographies that have taken shape during a journey that will never come to an end.32 As the first film of “The Trilogy of Borders,” with Ulysses' Gaze (1995) and Eternity and a Day (1998), The Suspended Step takes the audience on this journey to barren borderlands populated with lonely soldiers, across river valleys resonating with smuggled music, through transmission lines networked by refugee labor, and in waiting rooms like Florina built upon stories of pain. One may ask at this point, is Florina real? Does any of this represent reality?

Angelopoulos’s cinema brings a history of exile into focus by following stories of displacement. Although these films are not documentaries, they visualize history by turning the camera toward the reality of homelessness and endowing the notion of exile with a multidimensionality peculiar to the aesthetics of the Mediterranean. The visuality of the sea acts as a prism, generating a “refracted” subjectivity with changing, interrogative foci: Who is struggling? Who is watching? Who is being watched and by whom?33 All these questions are fundamental to the radical thinking that Angelopoulos hopes to evoke by means of the cinematographic image so that viewers can approach the geographies of displacement through a deep history of exile.

Each shot clarifies the historical consciousness structured by exiles of various sorts. Viewers should take deep breaths before skin diving into the depths of an unconscious state hidden between the frames. Angelopoulos describes this seemingly technical yet essentially political function of montage by contending that “each shot is a living thing, with a breath of its own, that consists of inhaling and exhaling.”34

Between inhaling and exhaling exists the Mediterranean, a saturated repository of lost gazes. These lost gazes arrest viewers’ own, indifferent gazes by calling attention to a collective suffering from a political future that is already lost at sea. It is important to rethink Sadek’s proposition here: How could we “linger” with this pain “which opens into another temporality and a set of concomitant questions regarding what sociality may remain or is still plausible” outside of a “protracted” Mediterranean?35 I would also ask, what sociality is still thinkable outside of the suspended step of the exiled? Is it even possible to imagine a form of sociality while we remain suspended in an existential sea of border-making?

Epilogue

The space of refuge is unattainable. There is nowhere to escape to. Borders extend through the sea to borderlands, and they connote ecologies and materialities other than the spatiality of refugee camps: marshes, rivers, bushes, deserts, and ruins that complicate the legal and political definitions of border-making. Florina is real in that it animates a history of exile through the everyday stories of the displaced who inhabit coffeehouses, streets, and railways. And those stories are not detached from history, making Florina not only real but also emblematic of limbo—of all times and all places. Urban settings along the coastlines of the Levant, North Africa, and Europe contouring the Mediterranean are now home to hundreds of waiting rooms, revealing the life of another sea made of fugitive landscapes. Landscapes of refuge give life to transient forms of life and makeshift livelihoods, including the agricultural fields that refugees work, the sweatshops that depend on their labor, the fringes of lower-class neighborhoods that they inhabit, or the migration management offices where they encounter the official languages of xenophobia.36

The Suspended Step provides a vision that juxtaposes the fluidity of the Mediterranean with a historical backdrop of imperial and post-imperial “state fixations” with border-making.37 By rendering a close-up account of the world witnessing a political crisis of unprecedented scale, the film simply argues that in no other moment than “now” will it ever be so pressing for us to question what it means to be a human. How will this journey end? There is nowhere else for me to escape to, right now, except perhaps for the poetic sanctuary offered by Etel Adnan:

The Final Judgment occurs uninterruptedly, like the sea. They define each other. And there’s something beyond time about these wars, this water. No question has been raised about the mind’s suspension within the universe’s suspension. No object moving. No subject watching. A mobility of another order. Mutability.38

We must mutate into new forms that cannot grant us immunity to silence and despair.

-

Etel Adnan, “Of Cities & Women (Letters to Fawwaz),” To Look at the Sea Is to Become What One Is: An Etel Adnan Reader Volume II, eds. Thom Donovan and Brandon Shimoda (Brooklyn & Callicoon, New York: Nightboat Books, 2014), 110. The title of this essay refers to the Mediterranean in the works of Theo Angelopoulos and Etel Adnan. Special thanks to Ana María León and Jacob R. Moore for their thought-provoking edits, comments, and questions. I also thank Joanna Joseph and other editors of The Avery Review as well as to friends, Zehra Hashmi, Haydar Darıcı, Daniel Williford, Raymond McDaniel, and Pınar Üstel for their valuable contributions. ↩

-

The Suspended Step of the Stork (Tο Μετέωρο Βήμα του Πελαργού), directed by Theo Angelopoulos (1991; Athens: New Star, 2006), DVD. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

As a tribute to Angelopoulos’s unfinished film The Other Sea (2012), Élodie Lélu portrays him as “the filmmaker of lost gazes” in the 2019 film Lettre a Théo (Letter to Theo). See also Andrew Horton, “Afterword: Theo Angelopoulos’ Unfinished Odyssey: The Other Sea,” in Angelos Koutsourakis and Mark Steven, The Cinema of Theo Angelopoulos (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 275–291. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Walid Sadek explains the Lebanese Civil War of 1975–1991 and its enduring legacies through the concept of “protracted war.” The concept unfolds as a “protracted now” for “the cyclical recurrence of violence,” and resulting processes of mourning continuously dominate everyday life in Lebanon. Sadek theorizes an active politics of “lingering” that requires a collective mobilization of “the labor of mourning” to create what he describes as “a temporal reversal, a turning around and a movement away from psychic convalescence towards the object of loss,” which might lead to “rebuilding a living sociality in the prerequisite presence of the corpse.” See “In the Presence of the Corpse,” Third Text 26, no. 4 (2012): 481–485. See also Walid Sadek, The Ruin to Come, Essays from a Protracted War (Motto Books & Taipei Biennial, 2016) and “A Surfeit of Victims: A Time After Time,” Contemporary Levant 4, no. 2 (2019): 155–170. For a parallel reading on urban conditions of unending war(s) in the Lebanese context, see Hiba Bou Akar, For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Fredric Jameson interprets the film’s title as emblematic of Greece in the 1980s, a period during which local histories of dictatorship, civil war, and exile crystalized into a kind of “melancholy.” As such, “the suspended step” represents, as Jameson argues, “the peculiarity of this space and this time alike,” right before the course of melancholy shifts “to what lies beyond that border: the Balkan War, the break-up of the ‘former’ Yugoslavia, an immense and bloody internecine conflict which seems virtually to replicate Greece’s earlier history on a larger scale.” Fredric Jameson, “Angelopoulos and Collective Narrative,” in Angelos Koutsourakis and Mark Steven, The Cinema of Theo Angelopoulos, 100. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. Emphasis added. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos’s cinema centers on an interplay between the themes of home, homelessness, and homecoming, directly referring to Homer’s Odyssey. At least one character in almost all of his films embodies a version of the mythical journey of Odysseus. See Andrew Horton, “National Culture and Individual Vision” in Theo Angelopoulos Interviews, ed. Dan Fainaru (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 88. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

See Mehrenegar Rostami, “Silent City: A Commemoration of Halabja’s Tragedy,” Music & Politics XI, no. 1 (2017): 1–16; Rebeen Hamarafiq, "Cultural Responses to the Anfal and Halabja Massacres," Genocide Studies International 13, no. 1 (2019): 132–142; Pierre Razoux, “The Halabja Massacre,” in The Iran-Iraq War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 433–442; Arun Kundnani. “The Halabja Generation,” in The End of Tolerance: Racism in 21st Century Britain (London: Pluto Press, 2007), 106–120. ↩

-

Yves Lacoste published a pamphlet in 1976—the same year he helped to establish Hérodote, a journal of geography and geopolitics in French—with the title of La géographie, ça sert, d'abord, à faire la guerre (Paris: Maspero, 1976). English translations of the title included “Geography is, above all, making war” and “Geography serves, first and foremost, to wage war.” Although Lacoste’s critique targeted the French academy in particular, it has had repercussions in English-speaking academic circles as well. I have used Lacoste’s claim that “Geography is, above all, making war,” in a literal sense that allows for explaining the historical transformation of the Mediterranean geography into a space of war-making in the hands of imperial and post-imperial states and military strategists. English translations are drawn from Stuart Elden, The Birth of Territory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 326; Virginie Mamadouh, “Geography and War, Geographers and Peace” in The Geography of War and Peace: From Death Camps to Diplomats, ed. Colin Flint (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 26. Turkish translations are drawn from Lacoste’s original text, see Coğrafya Savaşmak İçindir, trans. Aylin Ertan (Istanbul: Doruk, 2004). ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. Emphasis added. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Angelopoulos, The Suspended Step of the Stork. ↩

-

Geoff Andrew, “The Time of His Life: Eternity and a Day/1990” in Theo Angelopoulos Interviews, ed. Dan Fainaru (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 114. ↩

-

Etel Adnan, “Sea,” 257. ↩

-

Although outside the purview of this essay, it is worth noting that the question of what it means to be a human should be considered in a broader context. Here I turn to the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn’s seminal work How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). Kohn raises the question in the context of the Amazonian forests and traces “the human” through “a series of Amazonian other-than-human encounters” (p. 6). This kind of inquiry not only aims to expand the field of vision that has to do with how humans see and represent nonhumans but also puts forth a new analytic, an “anthropology beyond the human,” which allows for unsettling the ways in which humans see and represent themselves. Kohn’s project situates ways of thinking that are “distinctively human” in a broader world of “semiotic selves,” from which “the human” emerges. ↩

-

Kohn, How Forests Think, 5. ↩

-

For an analytic inquiry into “the suicide of the subaltern,” which informed the focus of this essay on the suicide of the displaced, see Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, “Death and the Subaltern,” in Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea, ed. Rosalind C. Morris (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 117–139. ↩

-

See Wendy Brown, “Politics and Knowledge in Nihilistic Times: Thinking with Max Weber,” Yale University Tanner Lectures of Human Values, October 22–23, 2019, link & link. ↩

-

Élodie Lélu, “Theo Angelopoulos: The Internal Journey” (Diwali Productions and Blue Bird Productions 2008). Also see Linda T. Darling, “The Mediterranean as a Borderland,” Review of Middle East Studies 46, no. 1 (2012): 54–63. ↩

-

Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 11. ↩

-

See Andrew Herscher, Displacements: Architecture and Refugee (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017). ↩

-

See Hakim Abderrezak, “The Mediterranean Seametery and Cementery in Leïla Kilani’s and Tariq Teguia’s Filmic Works,” in Critically Mediterranean: Temporalities, Aesthetics, and Deployments of a Sea in Crisis, eds. yasser elhariry and Edwige Tamalet Talbayev (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 147–162. For an ethnographic analysis revealing how the spatiality of refuge is deeply in crisis not only at sea but also on land, see Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015). ↩

-

See Lélu, “Theo Angelopoulos: The Internal Journey.” ↩

-

See Vangelis Makriyannakis, “The Poetics of the ‘Not Yet’ in The Suspended Step of the Stork,” Studies in European Cinema 11, no. 2 (2014), 126–138. ↩

-

See Karen Strassler, Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Duke University Press, 2010). ↩

-

Gerald O’Grady, “Angelopoulos's Philosophy of Film/1990,” in Theo Angelopoulos Interviews, ed. Dan Fainaru (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 72. ↩

-

Sadek, “In the Presence of the Corpse,” 482. ↩

-

Turkey is a case in point. For a critical reflection, see Bediz Yılmaz, “Refugees as Unfree Labor Force: Notes from Turkey,” Global Dialogue 9, no. 3 (2019): 33–35. I would like to thank Bediz Yılmaz for her patience and guidance during a very brief yet eye-opening journey to Turkey in the fall of 2016. ↩

-

See Raymond B. Craib. Cartographic Mexico: A History of State Fixations and Fugitive Landscapes (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004). ↩

-

Etel Adnan, “Sea,” 272. ↩

Seçil Binboga is a PhD candidate in the Architectural History and Theory Program at the University of Michigan. She is interested in relations between nature, space, and technology in the Middle East. Her dissertation explores how the American Cold War built Turkey’s territory into regional infrastructures of war and capitalism.