Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it. Sing or shout or testify or keep it to yourself: but know whence you came.

— James Baldwin1

Although I have often felt that I am standing on the edge of something, I have never felt that I have mastered the edge.

—Teresia K. Teaiwa2

This essay is about my architectural education. A reflection on what I learned, or, conversely, how little I learned about Indigenous understandings of the land, or about the built realm through a Pacific lens. I want to make sense of and accept (it still hurts how much time i spent learning about colonizers when i could have been learning about my people) why I learned about Corinthian columns before I learned why Pacific people often use their garages as secondary dwellings, and how that is connected to post–World War II New Zealand immigration policy. I want to examine why I did not learn about the dispossession of Māori from Indigenous land until a Māori academic taught me; or why, in a land surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, I didn’t learn about its many peoples and the multiple ways they conceive of space.

While this essay traces the arc of my own architectural education in New Zealand in the early 2000s through selective vignettes and insights, its object of review is the singular conceptualization of land and territories produced by the British Imperial project, as an enduring attitude toward the production and dissemination of knowledge in the architecture classroom. In the school where I received my architecture education, the students are increasingly from different backgrounds, worldviews, and positionings. Now that I am on the teaching side of the discipline, prioritizing what is taught, assessed, and valued is what I do for a living. But it is more than a livelihood for me when considering existential threats like climate change, and those more recent such as COVID-19. The Empire has failed Indigenous people and their communities, but it appears that it is now failing everyone—bar the extremely wealthy, and even they are getting sick. The Empire may not govern Aotearoa as it once attempted to, but its hierarchies still prioritize values from Western-dominated societies, and its architectural education reflects this fact. In turn, this hierarchy goes on to shape the values of practitioners that produce our built realms. Built environments can engender culture, affect well-being, and inspire for hundreds of years. The training that its students receive determines how people live. There is so much at stake. there is so much at stake.

In Aotearoa, New Zealand, where cities are still being actualized and housing stock is yet to meet demand, today’s architecture student is the bedrock on which the built environment of the next fifty to a hundred years will be formed. I want to figure out how to tell my students that what they are doing matters because the spaces they go on to make after school may include or exclude society’s marginalized and most vulnerable. They are going on to create signals that remind us what we strive toward and stand for. Reflecting on my own experience is as much a reflexive journey as a procedural one. By taking on my experience at the margins of architectural education, I want to know how to better teach and better understand—how to move away from Empire and toward community, to move away from territory and toward relationship, away from land as property and toward land as guardianship.

Curriculum: The things I learned

As a student at university, the curriculum reflected western value systems and seemingly employed few teaching staff with little reflexivity around how appropriate that was for a school in the Pacific region. this is my memory. As a student paying fees for a vocational degree, there was some pressure to pass these examinations and pass them well because it was so competitive—studio grades were posted on a public wall, and everyone would talk about who got an award at the end of semester. But there lingered for me a feeling that other dynamics were sorting us into different pathways. about twenty years ago i went to my first architecture class. i am still learning how to speak academic, it did not come naturally to me. university did not come naturally to me. at architecture school i had two educations, one was about a dominating european-american tradition of knowledge and taste. what i would call now a canonizing of the subjective. the other was about class, gender, and race. one education gave me grades, the other was ungraded, but it felt to me like it had something to do with the first.

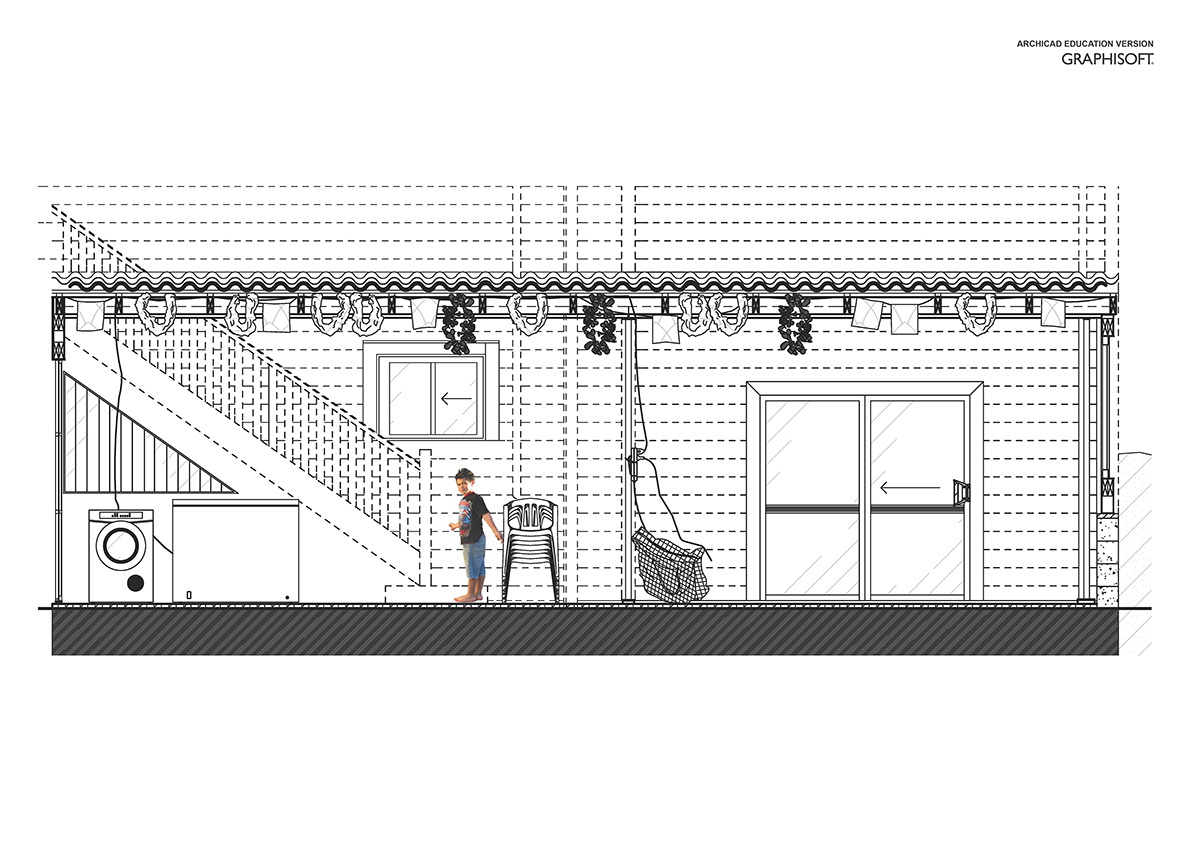

i was interested in this much wider classroom in which our architectural education seemed to be positioned, yet without specific language and context, my observations of class difference, gendered labor, and racialization remained a sensation rather than structures that could be understood. i saw and felt how gender and race divided my classmates’ experiences of the world, and how that shaped their architectural education. i was one of three pacific students out of 100 or so in my year. my brown peers and i found our own spaces to be ourselves in our class year, but i frequently noticed that our social geographies were embedded in the outlying suburbs of Papatoetoe, Ōtāhuhu, Māngere, and Ōtara, and that those territories were erased from our architecture education. i designed an art gallery in venice before i designed a community center in the place to where my people had been displaced.

People: The people who taught me, and the people I learned with

None of the tutors I ever had in school were Sāmoan or Indigenous to the Pacific. Looking back on it, there were moments when having a tutor from the same place as me would have helped. I was often paralyzed by imposter syndrome, brought on by the code-switching I had to do between my home life and my school life, my friends at architecture and my brown friends. I also had moments when I couldn’t function, like after my uncle died and I was in the school lab Photoshopping a photo for the funeral rather than getting ready for a crit. in the degree the atmosphere was always so aggressively competitive. i envied the people—usually men, usually straight, able-bodied, and almost always white—who seemed to know how to reproduce “good design” or even good taste, but more enviable still, who had no other commitments other than their pleasures and their studies, something some of them already called their “my work.” i had very different expectations placed on me by my family, which i think of now as expectations placed on them by their communities. they wanted me to be happy, and they also wanted me to keep my pacific values. these things don’t always fit together so well. especially in institutions. pacific students need advocates in institutional spaces, who have this lived experience, and they also need to know that their work matters, and that what they go on to do will determine wellbeing outcomes for pacific people. The Sāmoan way is a whole system that includes church, family, language, genealogies, traditional chief system, and social rites that convene these parts, or fa’a lavelave (all the ceremonial rites that accompany exchanges, which for diaspora involves sending money back to family in Sāmoa). while i did not spend my weekend at church like some of my Sāmoan friends, nor have the economic and cultural responsibility of fa’a Sāmoa, still my familial life was filled with the statistics associated with pacific diaspora in new zealand.

pacific migration was encouraged by new zealand’s government postwar to fill a low-income employment market. during my five years of architecture school, i attended funeral after funeral, as cancers associated with low socioeconomic backgrounds came to visit family members. my cousin on my father’s side died of colon cancer—she had been living with the cancer for so long it was too late by the time they found it. so did my uncle on my mother’s side. the disconnect between the labor that went into presentations at final crits and the type of labor i experienced and witnessed at home was something i couldn’t put into language, and often when i returned to school after a funeral, a hospital visit, or helping out at home, i felt uncertain, disorientated and it produced a feeling that i was ungrounded, without place.

i am not sure how my fellow pacific peers felt because we never talked about how we thought about difference. but i know i felt it. i would often look at others working so diligently (and often with the results i wanted, but was too proud to be outwardly disappointed when i didn’t get them), with so much commitment, while i had a seemingly eternal and constant banner running across my mind as i thought about space over the course of my undergraduate degree: “what are you doing here?”

A Place for Me: Indigenous knowledge systems

In April 2004, I took for the first time a course that focused on New Zealand Architecture, which organized Māori Architecture into three sections: traditions, renaissance, and contemporary. It was the last year of the first degree in my architectural education: a five-year professional architecture program made up of two degrees, the bachelor of architectural studies and the bachelor of architecture at the School of Architecture, University of Auckland. The then-new senior lecturer, now head of the School of Architecture and Planning, Professor Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu), was also the first Indigenous woman from Aotearoa to teach an architectural theory course in the school. I had never been taught Indigenous space concepts or history by a Māori woman prior, and I still remember thinking I was in the presence of something life-changing. It was the first time that the curriculum and my lecturer resonated with me. In the course, we were introduced to significant historical events and building movements for Māori iwi (describes tribal affiliations) and hapu (describes sub-tribal affiliations), their built surroundings, and the intangible dimensions contextualizing them. The course asked us to reflect on Indigenous architectures, as if the premise of Indigenous architecture as Architecture—not vernacular architecture, but capitalized “Architecture”—was already established. i loved it, and for the first time i felt like the education might have loved me back.

On reflection, dissolving the labor required of students to argue for establishing and valuing Indigenous spatialities, and by extension Architectures, dismantled a roadblock to understanding Indigenous worldviews and value systems for me, as an architecture student and as a Sāmoan woman. While I had some sense at the time of New Zealand as once a British colony, settler-colonialism and its impact for Māori and, to a degree, Pacific people was something that I thought of as historical and contained to the past, with little to do with the present. I understood that the Crown had issued explicit instructions to sever Māori from their ancestral lands but that it didn’t really seem like something that had anything to do with me at the time. I realized it was less that I had formed an opinion but rather that I had not been asked to think about it in my architectural education. Professor Brown taught me the canon of New Zealand Architecture by way of four key stories, the first being the land. In te reo Māori the word for land is whenua; this word also means “womb,” reflecting the worldview that all life springs forth from the ancestral Papatūānuku’s (Mother Earth figure) womb. The subtitles in the course outline were bilingual: 1. Take: Content, 2. Arotake: Assessment, 3. Nga Kauhau: Lectures, 4. Pukapuka Ako: Relevant Texts, Kiriata: Images. The first image for the course was Tane-nui-a-Rangi, Waipapa Marae, University of Auckland—the Māori meeting house of the university. Māori customary meetinghouses, known as wharenui, whare whakairo, or whare rūnanga, feature, through carving, ancestral narratives of the meetinghouses’ architecture. Whare in te reo is “house,” while whakairo translates to carving. The university’s whare whakairo is distinct in that it represents all major tribes rather than any specific tribe. While I cannot remember the image we were shown, I found a handwritten line on the course outline printout from sixteen years ago: “New World?” In my own notes I wrote: “Māori—ousted—marginalized and then relegated.” That was the first time I had ever considered the land as more than something you built on. A window opened onto a worldview where the land was more than landscape and boundary lines; it was the ancestral home to Māori. This New World I had found and documented in the margins of my course notes was the world of Indigenous knowledge systems thousands of years in the making.

Tūrangawaewae: Indigenous concepts that showed me another way

A fundamental component of belonging and identity in te ao Māori (Māori worldview) is the concept of tūrangawaewae. To translate from te reo Māori to English: tūragana can be understood as “standing place,” and waewae translated as “feet.” Brown describes it as, “one’s sense of belonging or attachment to a particular place and the ability to locate oneself there physically and spiritually. Personal whakapapa (sequences of descent or ancestry) are an expression of tūrangawaewae as they always begin with one’s waka (migratory vessel from Hawaiiki, the homeland), and include iwi (tribe, also the word for bones), hapū (subtribe, also the word for pregnancy), whare tipuna (meeting house), marae (forum on which the meeting house stands), maunga (mountain associated with marae or ancestry), awa (river associated with marae or ancestry), wāhi tapu/urupā (burial grounds), moana (harbor or sea), and tīpuna (founding ancestor of tribe).”3 In Aotearoa if one is to introduce themselves in te reo Māori, this order is followed, placing the individual speaking in genealogical time and geographical space across the ancestral, the land, and water. It follows that one gives their own name last in the sequence, the ordering of which can vary depending on each individual’s genealogy. In this way, in an introduction one communicates the relationships that have brought them to that moment, relationships not only to other people alive and ancestries but also to places both intangible and tangible.

This relational process of identification for relocated and dispersed Indigenous peoples like me can include customary and genealogical frameworks of belonging such as birthrights, sometimes birthrights that have been severed or weakened by settler-colonialism. In this way it can be a rite of self-determination that restores identity and resists western ideas that draw discrete lines between ourselves and the surrounding world. Professor of Māori studies and anthropology Dame Anne Salmond outlines these te ao Māori concepts organizing a human lifespan as better belonging in a cosmological framework: “In ancestral times, during their passage through the world of light, a person was tied so closely to their ancestral land that it was identified with their own body.”4 Reading this, I imagine strands of thinking that braid together how we ought to feel and consequently act in relationship with the land, as though it is an extension of our material bodies. If the British Empire thought of land as something to rule, te ao Māori has taught me it is instead something to be taken care of. My architectural education normalized the landownership model, but in Brown’s course, I was presented the land-guardianship model. Since then, I have only become more convinced that a land-guardianship model is vital and urgent to embed into an architectural education and that Indigenous teachers, tutors, and practitioners are integral to doing so in a meaningful way.

The Alternative Canon: Finding my footings

The final lecture of that New Zealand Architecture course was titled “The Alternative Canon.” The first words in the handout that day under the subtitle “He Kupu Hou: Vocabulary” were “Fale – Samoan House.” This was the first time I had encountered the word fale in my architectural education meaning something more than a hut. In the class, Sāmoan Architecture and its practitioners formed a canon, and I by birthright was a part of it. For my final essay, I wrote about the university’s Fale Pasifika, a building designed by New Zealand architect Ivan Mercep, a non-Indigenous architect, in collaboration with the university’s Pacific community. Brown would offer me a position as her research assistant the summer following. I had never before had an academic see potential in me—in fact, possibly the opposite had been true. My sense of things now is that being taught by an Indigenous woman about the architecture and practices of my people made the difference between my thriving in my architectural education and my going out into the architectural profession and struggling with a singular unquestioning perspective not only about the land but, more painfully, about the domain of Architecture residing in a European tradition. Now, as a lecturer myself, I remember my own experience in that course and think that students of all backgrounds and positionalities must be encouraged to find a place to stand, not just on land but in themselves, their own tūrangawaewae. This is also why it is so important that Indigenous academics, architects, and practitioners of other kinds are empowered to claim their birthrights in homelands and as diaspora, their relational ways to teach the alternatives so needed as Imperial models’ inherent limitations are exposed.

In 2018, I received my doctorate in philosophy in architecture. The University of Auckland did a small story on how, as far as current records showed, I was the first Sāmoan woman in the world to complete one. I found the doctoral journey fairly isolating, punctuated by grave loneliness, financial precarity, and depression. I just felt extremely lucky to have made it across the line and that the distinction of “first in the world” felt at odds with the sheer disbelief that I had completed what had always seemed impossible even while I was doing it. Once published, the story went viral in the global Pacific community. I was truly surprised, but when I look back to how I got started, I understand. i get it. Fundamental Māori concepts, Brown’s mentorship, and the alternative canon of Sāmoan architecture helped me find my footing and a place to stand in architecture. The “first in the world” designation speaks to my past experiences of marginalization and underrepresentation in my architectural education, but it need not speak to my future.

Epilogue

Prompted by this essay, I found myself reading over old ones. I found one completed for the New Zealand Architecture course sixteen years ago in which I discussed the work of architect John Scott, who identified as Māori (as well as Irish, Scottish, and English). I find that I reference an untitled response by Scott to the question of Māori influence in Architecture in a 1987 issue of NZ Architect, the industry journal for architectural practitioners in New Zealand at the time:

“Polynesian mores

Are inherent

In that BIRTH

ensures a place in ancestral company.

And when

Ancestors spirituality

minds reflect

then the ingredients presented

are there to

research, experience, extend and LIVE

in terms

relevant to time present and place.

And if ‘prejudices’ are tamed

Adjusted

And WE are that Ancestor

Who is the Aotearoa environment

that who relates

could be ARCHITECTURE

Hone Koati

Haumoana

John Scott.

Architect.

Haumoana.”5

I wrote as an undergraduate about the piece of prose: “[T]here is enough in our past for us to find a place among our predecessors as well as to ‘extend’ ourselves that which is the now. This ‘now’ that we create becoming the new precedent.”6

i wrote that so many years ago, and even though i find the sentence almost comically convoluted, the key idea has stuck. we may not live to see the changes we want; still we might feel strength in knowing that now is a bridge between the past and the future, and that is enough. we should sing, shout, and testify to that.

-

James Baldwin, “Introduction,” in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985 (New York, St. Martin’s Press/Marek, 1985), xix. ↩

-

Teresia K. Teaiwa “L(o)osing the Edge,” The Contemporary Pacific 13, no. 2 (2001): 343. Gale Academic OneFile, 344. ↩

-

Deidre Brown, “Tūrangawaewae Kore: Nowhere to Stand,” in Indigenous Homelessness: Perspectives from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, eds. Evelyn Peters and Julia Christensen (Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press 2016), 332. ↩

-

Anne Salmond, Tears of Rangi: Experiments across Worlds (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2017), 406. ↩

-

John Scott, “Maori Architecture – a Myth,” NZ Architect, no. 2 (1987): 37. ↩

-

Karamia Müller, “Shareable Space” (Unpublished Essay, University of Auckland, 2004), 3. ↩

Karamia Müller, PhD, is a Pacific academic specializing in Indigenous space concepts. Currently a lecturer at the School of Architecture and Planning, Creative Arts and Industries, University of Auckland, her research specializes in the meaningful “indigenisation” of design methodologies invested in building futures resistant to inequality. She is the project lead for the time-mapping research project, “Violent Legalities,” which presents interactive maps of Aotearoa, specially developed to plot historical instances of racial violence and tracks these against a chronology of legislative changes.