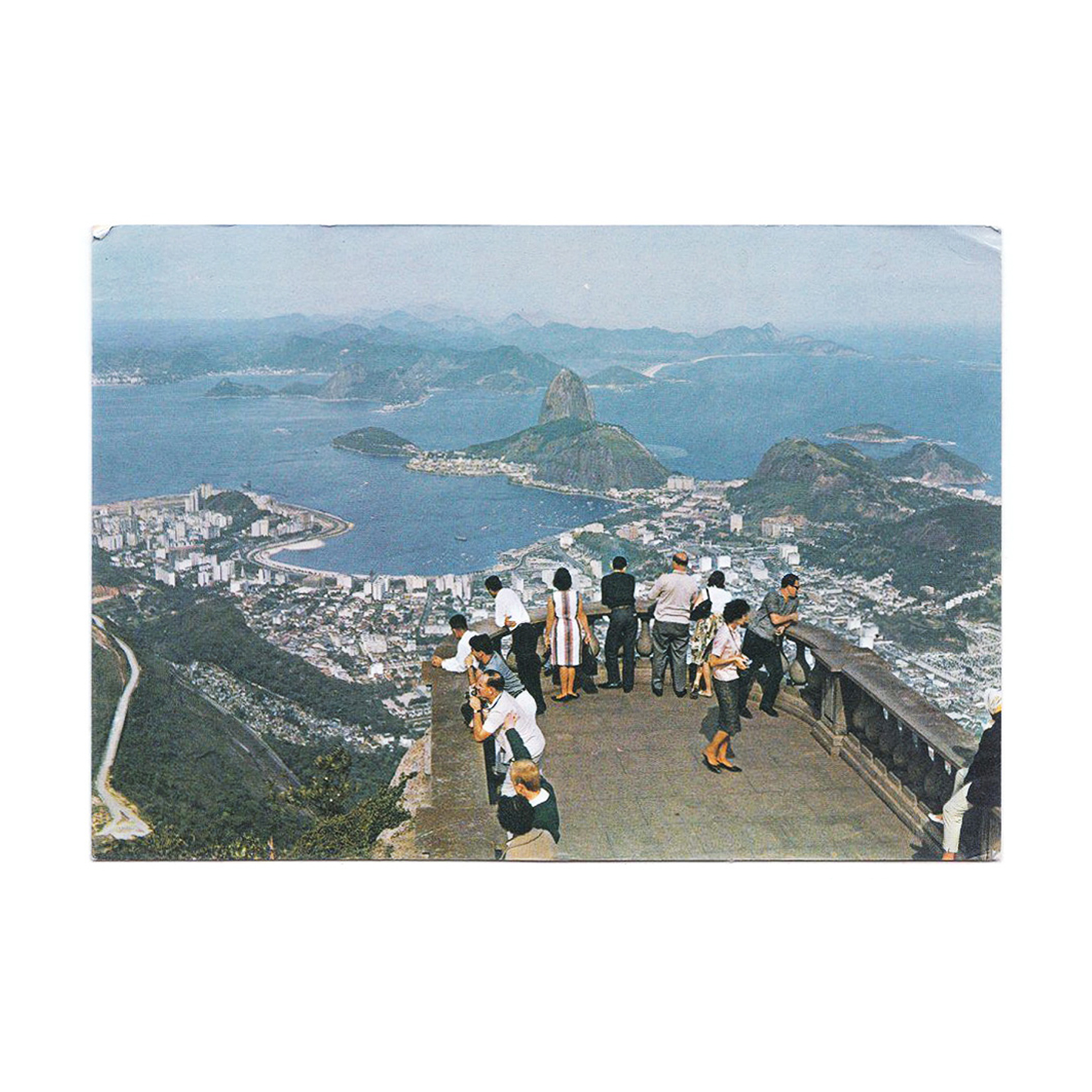

Within the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro, 36 percent of land is conservation area, nearly all of which sits 100 meters above sea level. In 2012, Tijuca, the mountain range that runs along the coast, was designated an “urban cultural landscape,” the first World Heritage Site of this kind, by UNESCO, advancing the city as a tourist destination. The densest of Rio’s neighborhoods have grown in between Tijuca’s ridges and valleys, encircling the freestanding massif. Yet use and access to the land by citizens and tourists alike is zoned and limited by a precise list of allowed activities—i.e., hiking, sightseeing, picnics—and opening hours.1 And while the aesthetic qualities of this topographical configuration are undeniable, there is no other force that shapes the city more socially and politically. In fact, setting apart unbuilt land into conservation areas shapes a territory beyond given environmental policies—revealing the way conservation might be seen as the impossibility of “use.”

The “void” of conservation created by Tijuca is not antithetical to the city but a product of the city. UNESCO’s criteria for an urban cultural landscape are a “creative fusion between nature and culture” and a “landscape that has had a high worldwide recognition factor.”2 The construction of such a “fusion” has been far from conflict-free and such “recognition” far from socially inclusive—from settler colonialism to ongoing eviction struggles.3 As conservation continues to get folded into a capitalist logic, it produces new modes of valuation that prevent the organization of society around use-value. The inability to think outside of this logic is perhaps one of the biggest obstacles to overcoming society’s problematic relationship to natural resources. Within and against such a universally adopted system of land use, architecture may facilitate a willing society to rethink conservation as a new mode of organization in which the commons are enabled rather than one based on securing economic reproduction. While the tropical, post-colonial, urban context of Rio includes site specificities, its role in World Heritage and National Park categorizations reflects similar struggles over natural resources elsewhere.

Traditional Western conservation discourse—from its origins as a way to revoke the rights of peasants to hunt in royal forests to contemporary land restrictions for future-proofing resources and objects of value—disallows any substantial notion of “use.” Use, in its most bare form, is the relationship to things insofar as they are not objects of possession but rather exist in the realm of the commons. The notion of commons implies a plurality of publics sharing resources and governing their own social relations and (re)production processes through doing so in common.4 Consumption—or in this case mass tourism—on the other hand, is the destruction of that commons where “use” is separated from “user”: things are rendered as exhibits to generate a commodifiable spectacle. As a concept, it is analogous to Giorgio Agamben’s notion of “museification,” where the potentialities that once defined a stretch of land are tamed, circumscribed in the glass box of the nature reserve.5 In Agamben’s framework, something that might acquire a different meaning through use is crystallized into an arbitrary meaning that cannot be used and, thus, cannot acquire new meaning. This is not to suggest an anthropocentric view of so-called nature devoid of meaning without human intervention: that would align too well with the history of endless resource extraction that has defined settler colonialism and capitalism. The rain forest is full of life on its own and the modern conception of “nature” itself is an invention of the West. Rather, it is to suggest that conservation has been a strategy of separation: an attempt to foreclose the possibility of understanding ourselves and our own activities relative to the activity of the protected biosphere. As citizens of subscribing states, we must always enter as guests, or as an “other,” and as such we continue to displace ourselves from the ecological dynamics that give shape to life on earth. We are the ones unchanging.

Separation in Agamben’s discourse refers not to the physical barrier preventing us from entering protected land—although that is an aspect of it—but to the separation of use from user. It occurs when “use”—in the form of visitation, environmental education, scientific research, religious ceremonies, fire monitoring, recreation, resource extraction, gardening, so on—becomes “consumption.” This distinction helps us understand that conservation areas may be considered the new enclosures of primitive accumulation—a concept defined by Marx as an appropriation of wealth (such as land) through direct action (such as expelling a resident population and enclosing land into private property).6 Rather than a historical process that preconditioned capitalism with the arbitrary privatization of common land in Europe and with settler colonialism in Brazil, it is an ongoing one that takes on different forms of expropriation processes.7

To conserve is to construct a narrative for what is to be conserved. Whoever controls conservation controls the narrative. As a mode of organization, it has been used to erase previous histories and subjugate certain forms of life. As a maneuver of the ruling class, conservation makes the work of culture appear to be the work of nature. The paradoxical nature of conservation is revealed through “use.”8 There are, of course, different uses of “use” and these differences matter. For Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, if a conservation area is not fomenting the economy with tourism, for instance, it is a wasteland, it is “unused” and in need of improvement, which comes in the form of being “used” for the extraction of natural resources or agriculture. The implications and violences of his policies were made explicit during the Amazon fires of 2019 and 2020, linked to land-clearing. Bolsonaro’s government has proposed legislation to loosen environmental restrictions, open Indigenous reserves to mining, and “regularize land titles.” The latter proposal implies officializing forms of landownership as “the result of invasions of protected land,” which means it “reward[s] land grabbing.”9 Such acts of “loosening,” “opening,” and “regularizing” land are paradoxically ideologically aligned with acts of “enclosure” insofar as they serve to perpetuate economic reproduction through direct action. Questioning use implies that some things we do, things we are asked to get used to, are in the way of a project of living differently.

Anything but Natural

What is being conserved in Tijuca is anything but natural. It is estimated that the area around the mountain had been inhabited by pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers for 11,000 years and, since the year 400, by the Tupi people.10 In 1557, laying the groundwork for colonization, missionary Jean de Léry recorded twenty-two tribes in the area and a network of hunting trails across the mountain.11 In 1565, the territory was taken over by the Portuguese, and the land encompassing Tijuca was redistributed according to the sesmarias system—granted to the missionary Society of Jesus, the City, and the landowner Manuel de Brito.12 The system did not grant private landownership but rather conscripted the grantee to cultivate the land on behalf of the crown. This colonial arrangement relied on indoctrinating Indigenous communities—the colonizer was positioned as “the legitimate carrier of culture and civilization to barbaric and lost peoples”—and was carried out through mercantile interests.13 New landowners extracted timber, produced charcoal, grew crops, monopolized water sources, and resold land.14 This “physical [re]occupation and use of the land,” as Brenna Bhandar explains, formed the basis of ownership “defined quite narrowly by an ideology of improvement in settler colonial contexts.”15 Land was occupied by virtue of denying that those living on the land were using—according to a western notion of agriculture—the land.

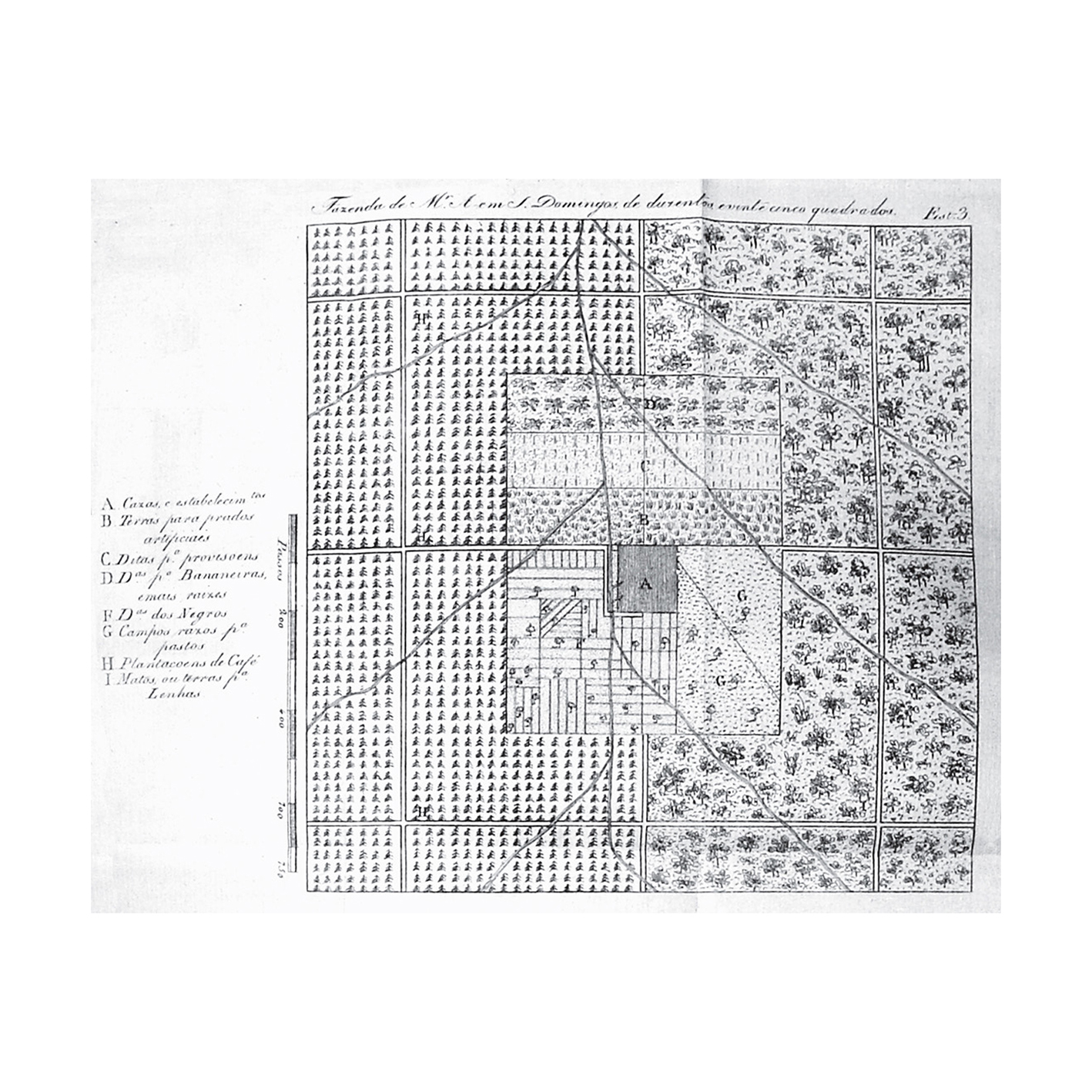

Cultivation of Tijuca and its surrounds peaked in the early nineteenth century when plantation owners found in the hillsides the perfect condition for the bourbon coffee seed (coffea arabica): evenly distributed rainfall and no standing water. This “discovery” at Tijuca ushered in a wave of tree planting—as deforestation followed by cultivation, justified by the existence of untapped resources, a process not dissimilar to Bolsonaro’s policies—which came to define the so-called First Cycle of Coffee in Brazil. Frenchman Louis François Lecesne’s plantation of 1816 was the largest with 50,000 coffee trees employing over fifty African and Indigenous slaves.16 Plantations were modeled on the 1798 French-Caribbean treatise The Coffee Planter of Saint Domingo, written by Pierre-Joseph Laborie, which proposed spatial forms contingent on racial difference.17 The treatise outlined the construction of terreiros—loosely translating to “yard” or, in this case, the “drying yard”—determined by the number of slaves.18 It provided detailed instructions for building terraces on sloped terrain, for retention walls, for compacting soil, drainage, pavement, and semicircular extrusions in order to keep harvested beans dry. When not sorting beans, many of the enslaved people who worked on the land would also, in acts of subversion, (mis)use the terreiro to host their cultural ceremonies—often in secrecy and risking punishment. To this day, some groups of African origin, such as the Camdomblé, refer to gathering spaces of emancipation as terreiros.19 This archetype was, at once, a spatial synthesis of production and a platform for social encounters. Depending on position, it either attempted to secure the link between property and racial subject or attempted to subvert that determination altogether. Spatial form that was designed for racial property regimes was also creating a history of fugitive, emancipatory “misuse.”

Contrary to notions of a pristine forest, Tijuca today contains all these histories and potentialities. It is the accumulation of all these radically different formal-social configurations. The rain forest was superseded by the regular layout of coffee trees; topography was adjusted into terraces and pathways for production and access; waterways were channeled for sourcing and irrigation; and Christian chapels were built to establish a network of congregations; the list goes on. But these destructive spatial configurations did also set the stage for subversive anti-colonial acts such as the self-organized social cooperation enabled by the terreiro. What is important here is not restoring a use that may or may not be relevant today but that these shifting uses continuously gave new meaning to the land, as opposed to today’s static uses.

Constructing Conservation

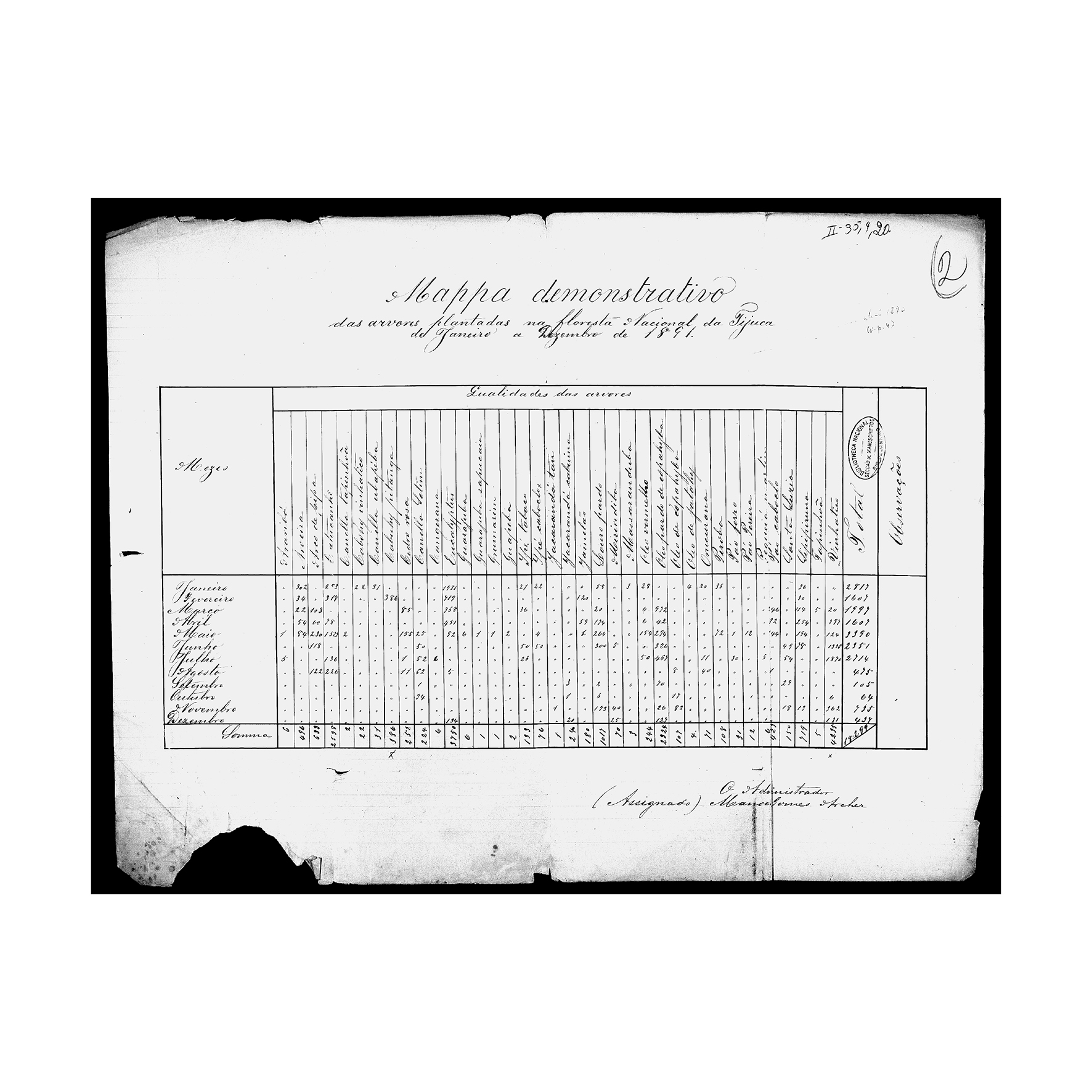

The current form of Tijuca mountain, that which justifies conservation, is also a construct driven by similar forces. In 1861, plantation land was once again forcefully dispossessed—this time by the recently independent Empire of Brazil—into the so-called Imperial Farm (Fazenda Imperial).20 An Imperial Decree appointed Major Archer to reforest the hillsides as, by that point, “all virgin rainforest… had been knocked down” to give way for plantations.21 The official claim for dispossession on behalf of the government—i.e. restoring springs to supply demand for water in the city—was not entirely substantiated.22 A better way to understand this redistribution of land, which establishes the project of conservation as a long-term management of resources, perhaps lies in the fact that (re)appropriated land was named a “farm” and not a “forest.” This reveals that reforestation was, at first, seen as a strategy geared toward efficient farming rather than the restoration of original vegetation. As the agrarian elite foresaw the official abolition of enslaved labor, the silviculture project was to be an experiment in regenerating exhausted soil for further cultivation while at the same time growing future timber for harvest. The madeira de lei (“wood of law”)—referring to a group of indigenous hardwoods that were declared as the most adequate for naval and railroad construction—was favored.23 As can be seen from his meticulous yearly reports, Archer planted a total of 80,000 trees, out of which 55,000 thrived among an existing 16,000. His successor would plant another 35,000 trees. The Imperial Decree marked the beginnings of political agency behind conservation. Tijuca being in Rio, then the capital city, would set the example for conservation in Brazil.

In 1874, Gastão d’Escragnolle became administrator and, aided by French architect Auguste Grazou, envisioned turning some of these planted forests into public parks and giving them a “natural treatment” similar to Bois de Boulogne.24 Ironically, and similar to the process that would ensue in Brazil, the Parisian park was originally a gridded hunting ground only later redesigned with picturesque pathways. Under d’Escragnolle, the jungle was to become a “harmonic” place for strolling with gravel trails, stone bridges, grottoes, artificial lakes, belvederes, and a Chinese pagoda. Establishing “harmony” also involved officially demarcating a hillside as “Tijuca Forest,” advertised as offering “picturesque tours and replenishing picnics.”25 The park reemerged as a way to prescribe a specific civic subjectivity through nature’s symbolic representation of the social order. Notions of slave labor and foreign dominion were replaced by new symbols of pragmatism and public utility. Memory formation (or erasure) and policymaking evolved in tandem to establish an illusory mutuality between individual desire and the common good.

Following the 1889 fall of the empire and the establishment of a republic, the park entered a period of neglect. But in 1943, Raymundo Castro Maya became the administrator of Tijuca Forest and was charged with continuing the work of his predecessors to create “the example… of what a national park could be.”26 This was in line with the first comprehensive masterplan for Rio—drawn up by French architect Alfred Agache in 1930, who wrote that “Rio is above all characterized by a mountain range that makes it an ideal touristic center.”27 During the rest of the twentieth century, Tijuca mountain was increasingly circumscribed into a mosaic of UNESCO, national, state, and municipal conservation areas with the aim of securing the city as a tourist destination. In 2011, the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Master Plan established that “urban policy will be implemented based upon… natural heritage,” for “landscape represents the most valuable asset of the city.”28 Today, Tijuca mountain is the most visited conservation area in the country, with about two million visitors a year. The seemingly native condition of what one sees today is indeed deceiving. What is preserved in today’s forest is the set of state-sanctioned practices carried out to advance shifting ideologies: with each new conception of nature, a new method to exploit the land and its subjects.

Impossibility of Use

Tourism represents the core of capitalist thinking.29 It is not just that objects are stripped of use when put on display, as Sara Ahmed explains, but that the communities for whom objects matter are stripped of what matters to them.30 In the case of Tijuca, this dispossession has taken many forms from the state’s attempt to break Indigenous peoples’ ties to the land, evict descendants of slaves from the hillsides, deny residents of the region foraging activities, and so on. In the 2000s, so-called environmental walls—three-meter-high blockwork structures covered in ivy—were built by municipal authorities to allegedly protect parts of the land by denying access to it. What does it mean to shift land use toward tourism in this way? Who and what gets foreclosed in the process? What publics and counter-publics are created? While those favored to enjoy access to the land—tourists and traditional conservationists—may generate communities in and of themselves, these are disenfranchised from creating new meaning for the land by mechanisms that favor economic expansion. In this sense, the conserved mountain mirrors and replicates a value system rooted in class structure. As these modes of managing so-called unbuilt land are increasingly the go-to approach in Brazil and elsewhere, the more they constitute new forms of primitive accumulation and the less we are able to enter into a new paradigm of use.

Land theft is justified as taking care of things by taking them out of common use—from settler colonialism to the contemporary criminalization of certain subjects. The 1861 Imperial Decree punished “cutting down trees and non-authorized hunting,” and implemented a new forester force to expel runaway slaves, criminals, and individuals fleeing urban epidemics.31 In fact, one of the biggest quilombos, or maroons settlements, housed over a thousand inhabitants on the hillsides of Corcovado peak.32 Today there are still supervisions, checks, and inspections, which utilize incremental, geo-referenced surveillance systems to remove anyone using the land outside the list of allowed uses.33 This “site management” is carried out across an area of 3,958 hectares with a buffer zone of about 6,465 hectares—almost eight times the size of New York’s Central Park. Such structuring of space ultimately assigns commodifiable value to a territory that may not necessarily have been defined by exchange equivalencies on the market—a story well told by E. P. Thompson in the UK context of the eighteenth century and by Karl Jacoby’s “hidden history” of US conservation laws since the late nineteenth century.34

The application of these laws has been strategic. It is not coincidental that it was also in the 1960s—when the National Park and major conservation legislation was created—that Brazil began to enter the global market economy and, after 1964, a military dictatorship governed it. Conservation was called upon to justify removing slums from hillsides around wealthy neighborhoods, located mostly in the south side, near the coast. In their place, “greenery” reaffirmed property value and enlarged the physical separation from the working-class north side. Such politics also had an impact on urban infrastructure. Along Tijuca’s longest ridge, which divides the south and north sides of the city, the mountain is only penetrated by a single tunnel. In the words of local geographer Maurício Abreu, “the support [of the mountain] facilitated the development of a compartmentalized urban structure, where stratifications projected by socio-economical levels are concretized.”35 Such urban stratifications were justified by rendering things into a state of permanent crisis, allowing political agency to act without restraints.

Conservation is hegemonic because it appears as the natural, ahistorical way of managing unbuilt land. It successfully establishes a legal framework to govern struggles over natural resources. However, the substitution of fluid social agreements for law relegates all negotiations over land use from local inhabitants to the ruling authorities. The modes of governance developed during the era of colonial expansion have been perfected by neoliberal rationalities. The distortion of social issues into natural ones is hidden by assigning to “values” contents commeasurable with methods of production. Tourism is institutionalized, the mountain is rendered untouchable, and social tensions are crystallized.

The Mountain as a Project

Conservation is not the enemy of modernity but one of its inventions. Tijuca National Park’s 2008 Management Plan has a “consulting council” composed of two “technical boards,” one for tourism and one for protection, making its driving forces clear.36 All decision-making is presided over by the Conservation Institute (ICMBio), under the Federal Ministry of Environment (MMA).37 The UNESCO site answers to a special “management committee,” chaired by the Heritage Institute (IPHAN), and it is composed of key stakeholders both from the public and private sectors. While subscribing the mountain to such overarching mandates helps create a governance for conserving the area’s current iteration—in this case, the forest—it bypasses social conflicts and narrows public policy down to the question of how to enhance tourism.

Today, conservation is indeed perhaps the only juridical instrument capable of keeping developers from building. The 2008 Management Plan sets out two overall categories of land use: “integral protection” and “sustainable use.”38 The former distinguishes restricted areas from those accessible to the public. The public at large is encouraged to visit, within opening hours, for “recreation.” “Sustainable use” falls within the peripheral buffer zones, where “the use and occupation of the land [are] regulated.”39 Listed views and geological formations are also protected. UNESCO moreover instructs implementing, “if found necessary, more restrictive soil use and occupation parameters.”40 In fact, when such institutions conserve meaning by stripping an object from use, what they are conserving is not a meaning but the rights of some to decide what and who counts as meaningful. As a mechanism of land appropriation, the Tijuca conservation area converts “use” into “tourism,” the commons into the space of consumption.41 Agamben offers the term “profanation” as a counter-mechanism that could restore to common use what consumption has separated. To profane the mountain would mean not to abolish the conservation mechanism but to learn to put it to a new use.42 Or, following Ahmed: to use it in a way it wasn’t intended, to misuse it, for those who it wasn’t intended for.43

By decolonizing the histories and potentialities of an enclosed site, we may rethink modes of conservation and form alliances and communities that develop alternatives to its logic of consumption. “Use,” as essential to the notion of commons, offers such alternatives. As Massimo De Angelis suggests, at a general organizational level, a commons system involves at least three constituent elements: first is the pooled material and immaterial resources; second is a community of commoners, or subjects willing to share, pool, and claim collectively; third is doing in common or is a specific multifaceted social labor through which resources and commoners are (re)produced together with the (re)production of things, social relations, solidarity, self-valorization, decisions, and cultures.44 There already exists arrangements such as unclaimed land being used for allotments in Morro da Formiga and an ecological park created by the neighbors of Vidigal. Thinking the mountain as a commons and as a site of social forces would represent a meaningful challenge to established modes of enclosing land.

How the commons reframes core tenets of conservation for Tijuca National Park and its UNESCO site might mean, at a governance level, restructuring who is considered a constituent and who is given decision-making power (i.e., small, civil-society groups that propose varying modes of land management and social compositions over technical bureaucrats). It might mean that notions of pristine nature be reinterpreted with histories of Indigenous, African, and fugitive publics. And that circumscribed land expands and reshapes its boundaries without the need for direct action by the state. It might mean radically rethinking how humans “use” a landscape without overusing it. The problem has been that when conservation tries to set a limit to land use, it folds use into a logic of economic reproduction instead of reproduction of social cooperation for sharing resources and for establishing new cultures in relation to the biosphere. Unless there is a concept of “limit,” then the limit to capitalist logic may never be found. One must here differentiate “separation” from “limit.” While one separates use from user—to echo Agamben and Marx—the other is an inherent aspect of the commons in the form of protocols and policies that, if collectively constructed by negotiation among the users of the land, may construct shared spaces that can be used without stopping them from being usable. Such limit to use would not live within a utopian condition of the total abolishment of property. Instead, it considers the existing and latent associations of people whose practices and use of space falls outside dominant modes of production preconditioned by landownership. Thus, the commons may become a vehicle for new categorizations of “use” within Tijuca that are paired with certain practices—social, cultural, and ecological—to reframe what entails a so-called urban cultural landscape, ushering a new set of land practices that may overcome our current capitalist-consumptive paradigm.

-

Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio), Plano de Manejo: Parque Nacional da Tijuca (Brasilia: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, 2008), 5, link. ↩

-

UNESCO, “Decision: 36 COM 8B.42 Cultural Properties - Rio de Janeiro,” July 6, 2012, link. ↩

-

See, for instance, the ongoing legal battle between municipal authorities and the settlement Horto Florestal. The area’s inhabitants—descendants of African and Indigenous slaves who worked on local plantations as early as the sixteenth century—are being forced into eviction. The Botanical Gardens, part of Tijuca Park’s forestry efforts, claims the land belongs to them. See Anne Vigna, “No Rio, Comunidade Fundada no Tempos da Escravidão Luta Para Ficar,” March 16, 2017, link. ↩

-

Massimo De Angelis, Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism (London: Zed Books, 2017), 10. ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, “In Praise of Profanation,” in Profanations (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 83. ↩

-

According to Marx, separation is the precondition for the accumulation of capital where an “original” appropriation of wealth occurs through “direct extra-economical forces.” See Karl Marx, “Part Eight: So-Called Primitive Accumulation,” in Capital Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin Books, [1867] 1979). ↩

-

See works by Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital (New York: Routledge, [1913] 2003), Hannah Arendt, Imperialism (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1968), and David Harvey, “The New Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession,” Socialist Register, no. 40 (2004): 63–87. ↩

-

Conservation saves everything we have come to call the “natural environment,” and it separates the free use of land into the sphere of consumption. ↩

-

Dom Phillips, “Resistance to the ‘Environmental Sect’ is a Cornerstone of Bolsonaro’s Rule,” The Guardian, link. ↩

-

Warren Dean, With Broadax and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 38–39. ↩

-

Paulo Bastos Cezar, et al., A Floresta da Tijuca e a cidade do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1992), 21. ↩

-

Maurício de Almeida Abreu, “A apropriação do território no Brasil colonial,” Escritos sobre espaço e história, comp. Fania Fridman and Rogério Haesbaert (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Garamon, 2014), 268–270. ↩

-

Renata Malcher de Araújo, As cidades da Amazónia no século XVIII: Belém, Macapá e Mazagão, second ed. (Porto: Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto publicações, 1998), 41. ↩

-

Maurício de Almeida Abreu, “A cidade, a montanha e a floresta,” Natureza e Sociedade no Rio de Janeiro, ed. Maurício de Almeida Abreu (Rio de Janeiro: Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, Turismo e Esporte, 1992), 56. ↩

-

Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 34. ↩

-

Together with Dutchman Alexander von Moke’s plantation, which had 40,000 trees, Lecesne’s plantation occupied the area known as Gávea Pequena, an elevated valley on the south of the mountain range. The eastern hillsides of Corcovado peak featured Englishman Chamberlain’s plantation, with 20,000 trees. The Boa Vista valley, high up on the center of the mountain range, accommodated Frenchman Gestas’s plantation, with 30,000 trees. The northern Elefante valley was occupied by Rudge’s and Devel’s plantations. Additionally, contemporary newspapers feature advertisements that indicate plantations all over the mountain. See Gilberto Ferrez, Pioneiros da cultura do café na era da Independência (Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, 1972), 32, 48, 49; and Abreu, “A cidade,” 71–72. ↩

-

Rafael de Bivar Marquese, “Luso-Brazilian Enlightenment and the Circulation of Caribbean Slavery-Related Knowledge,” História, Ciências, Saude–Manguinhos 16, no. 4 (2009): 855–880. ↩

-

Lecesne’s plantation had “terreiros of some 25 to 30 ft2 constructed of bricks or pressed clay in a convex shape so rain could drain off [and] 15 kg of beans could be spread out for over a month.” See Johann Baptist von Spix and Karl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, Viagem pelo Brasil (1817–1820), vol. 1 (São Paulo: Editora USP, [1823] 1981), 84–86. ↩

-

For further reading on slave life and fugitive documentation in Rio, see Mary C. Karasch, Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro: 1808–1850 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019). For a history of Camdomblé, see Paul Christopher Johnson, Secrets, Gossip, and Gods: The Transformation of Brazilian Candomblé (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). ↩

-

Emperor of Brazil, Decree no. 577 of December 11, 1861, “Instruções provisórias para o plantio e conservação das florestas da Tijuca e Paineiras,” link. ↩

-

Description by botanist George Gardener from 1836, in Abreu, “A cidade,” 77. ↩

-

Scientific commissions in 1861 and 1870 advised water had to be sourced elsewhere, namely from the nearby Tinguá mountains, for the city’s demand to be truly met. Disappropriation of land at Tijuca mountain continued until at least 1885. See Abreu, “A cidade,” 79, 82; Maria Luiza Gomes Soares, “Floresta Carioca: A interface urbano-florestal do Parque Nacional da Tijuca” (MA diss., Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, 2006), 148, 160–1; and Claudia Beatriz Heynemann, “Natureza e Civilização no Brasil na Segunda Metade do Seculo XIX: A Floresta da Tijuca,” (MA diss., Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, 1994), 50. ↩

-

The decree’s “provisional instructions” dictated that planting be undertaken in rectilinear, parallel lines with distances of 5.7 meters between trees, starting at the strands of water springs. This was complementary to previous instructions dividing the area “into squares of [183m] each” for planting “madeira de lei” trees aligned to contour lines. Other species, especially from Archer’s own farm, were also introduced to help fast-track the growth, albeit in smaller numbers. See document of 1846 issued by the Public Works Inspectorate (Inspetoria de Obras Públicas). In Abreu, “A cidade,” 77. ↩

-

Carlos Manes Bandeira, Parque Nacional da Tijuca (São Paulo: Makron Books. 1994), 88–89. ↩

-

See Perez & C., “Propaganda: Empreza de carros de aluguel da Serra da Tijuca” (Rio de Janeiro: Angelo & Robin, 1878), link. This market- and leisure-oriented reconfiguration extended to other sites as well. Rocky peaks, such as Corcovado, were celebrated for their vistas. A railway to its 710-meter summit was inaugurated in 1884, introducing a new relationship between the mountain and the city. For the first time, the public at large could overlook the entirety of urbanization and its distribution among the mountains. An awareness of one’s position within the spatio-social spectrum was created and made legible. ↩

-

Raymundo Ottoni Castro Maya, A Floresta da Tijuca (Rio de Janeiro: Bloch, 1967), 11. ↩

-

Administrator Maya echoed the importance of restoring the mountain “for the contemporary tourist.” See Alfred Agache and Prefeitura do Distrito Federal, A Cidade do Rio de Janeiro: Extensão-Remodelação-Embellezamento (Paris: Foyer Brésilien, 1930), XLI; and Maya, A Floresta, 29. ↩

-

Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro, Complementary Law no. 111 of February 1, 2011, “Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Urbano Sustentável do Município do Rio de Janeiro,” link. ↩

-

Agamben, “In Praise,” 84–85. ↩

-

Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 33. ↩

-

Heynemann, “Natureza,” 41. ↩

-

Mary C. Karasch, A Vida dos Escravos no Rio de Janeiro: 1808–1850 (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2000), 408. ↩

-

National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN), “Site Management Plan: Rio de Janeiro: Carioca Landscapes Between the Mountain and the Sea” (February 2014), 61, 127, link. ↩

-

See E. P. Thompson, Whigs & Hunters: The Origins of the Black Act (London: Breviary Stuff Publications, 1973) and Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↩

-

Maurício de Almeida Abreu, Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro, fourth ed. (Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Pereira Passos, 2013), 18. ↩

-

ICMBio, Plano, 3–4. ↩

-

IPHAN, “Site Management,” 44. ↩

-

The 2008 Plano (by ICMBio) was set out by Presidência da República, Law no. 9,985 of July 18, 2000, link. ↩

-

Prefeitura, “Plano Diretor,” Ch. I, Sec. II, Art. 14. ↩

-

Giorgo Agamben, “What Is an Apparatus?” What Is an Apparatus? And Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 12, 19. ↩

-

Agamben, “In Praise,” 85–92. ↩

-

Ahmed, What’s the Use?, 199. ↩

-

De Angelis, “Omnia,” 119. ↩

Roberto Boettger is an architect based in Rio de Janeiro and London. He studied at the Architectural Association and has worked with 6a Architects and OMA. Roberto has been the recipient of the RIBA Wren Scholarship, Valentiny Foundation Award, AA Bursary and nominated for the RIBA President's Medal. He has taught at the AA and other universities. His writings have featured on the AR, AU, Domus, Kerb, Pidgin, and other journals.