The concept of the political has no precise, corporate image… Yet the political seems to have as a characteristic the quality of arranging the relationship of things and of people within some form of society.

—Cedric J. Robinson, The Terms of Order1

On October 17, 2019, New York City’s Mayor Bill de Blasio announced, “Today we made history: The era of mass incarceration is over. It’s over.”2 This statement, made at New York City Hall, came after the City Council approved De Blasio’s plan to replace Rikers Island Correctional Facility (Rikers), the 415-acre jail island located between the Bronx and Queens, with four new “borough-based jails” by 2026. In the clip, posted on the mayor’s Twitter profile, De Blasio stands tall at a blue velvet-draped podium bearing the New York City seal. De Blasio sports a suit. He is backed by a gold-framed portrait of Alexander Hamilton and an “entourage” of six individuals, four of whom are Black. The individual to his left wears a blue shirt with white lettering that reads “Katal: Center for Health, Equity, and Justice.”

This scene is a deliberately curated arrangement of things, which, as Cedric J. Robinson poignantly argues, rehearses the status quo in order to curate a specific form of society. The room’s lavish interior appears to match the perverseness of the carrier, De Blasio, and his message, which claims the end of mass incarceration while simultaneously announcing its proliferation by means of new jail construction. The image portrays a multiracial group, led by a white man, standing together to combat the inhumanity of a dilapidated jail complex; yet their victory cry is only victorious for those who believe that “dignified design” is the solution.3 Robinson, understanding the logics of reform, clarifies that “order is not only represented by the visual experience of patterns seen suspended in one space and one time, but perceived as well as suspended through successive dimensions of space and periods of time. That is to say that order can be seen in design—in place, or order can be seen in lawfulness—over time.”4 The spatialization of order, thus, not only curates this scene but backlights the layered films of colonization and capitalism that brought this particular event to the twenty-first century.5

While still requiring physical walls, the spatial manifestations of order are diffusing into invisible logistics, permeating ever more into the commonality of urban space. The dissolution of one of the world’s largest penal colonies into a series of more inconspicuous facilities throughout the city will not increase societal awareness, as reformist agendas claim, but rather it will allow incarceration to be further disguised and woven into accepted urban futures. Angela Davis has long positioned the prison in the sphere of magic; a typology that can disappear from public view those deemed undesirable to the never-ending quest for social order. However, “once that aura of magic is stripped away from the imprisonment solution,” Davis writes, “what is revealed is racism, class bias, and the parasitic seduction of capitalist profit within a system that materially and morally impoverishes its inhabitants, while it devours the social wealth needed to address the very problems that have led to spiraling numbers of prisoners.”6 De Blasio’s precariously premature statement aims to sell a palatable reformist horizon, all the while extending the carceral net’s capacity to, in Davis’s words, continue disappearing disposables for the maintenance of order.

Under the moniker of “borough-based jails,” the program to replace Rikers entails the construction of four new facilities in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. The “social benefits” listed to garner support for the proposal address the dilapidated state of Rikers and the need to replace it with a “modern and humane” system.7 The environmental, physical, and material realities of Rikers are undeniably detrimental: the sprawling carceral complex sits on hundred-year and five-hundred-year flood zones and is flooded regularly; the concrete-, steel-, and cinder-constructed buildings effortlessly absorb outside temperatures, whether 7 degrees Fahrenheit or 97 degrees Fahrenheit, and most cells are not climate-controlled; the decomposing landfill below these jails coats the entire island in rotten odors, which mix with pollutants pumped into the air by the multiple surrounding power plants, waste transfer stations, and a compressor station.8 These issues all existed before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, which has only served to exacerbate these violent conditions endured by those held captive there. New York’s current carceral infrastructure—and the state of Rikers and jails across the city—cannot be ignored. Yet, a responsible dose of skepticism about the “benefits” of the city’s plan is required. The moral complexity deeply woven into the “borough-based jails” proposal is perhaps best understood according to the logics of the “lesser evil.” 9 By framing the current carceral structure, Rikers Island, as the greater evil that can taint the city’s ethical reputation no longer, shiny new jails emerge as a favorable alternative that will “solve” the cruelty of its predecessor. However, the true outcome of continuing to bear repackaged carceral offspring in the name of reform is inescapable. It is the restraint of evil that mobilizes its proliferation.

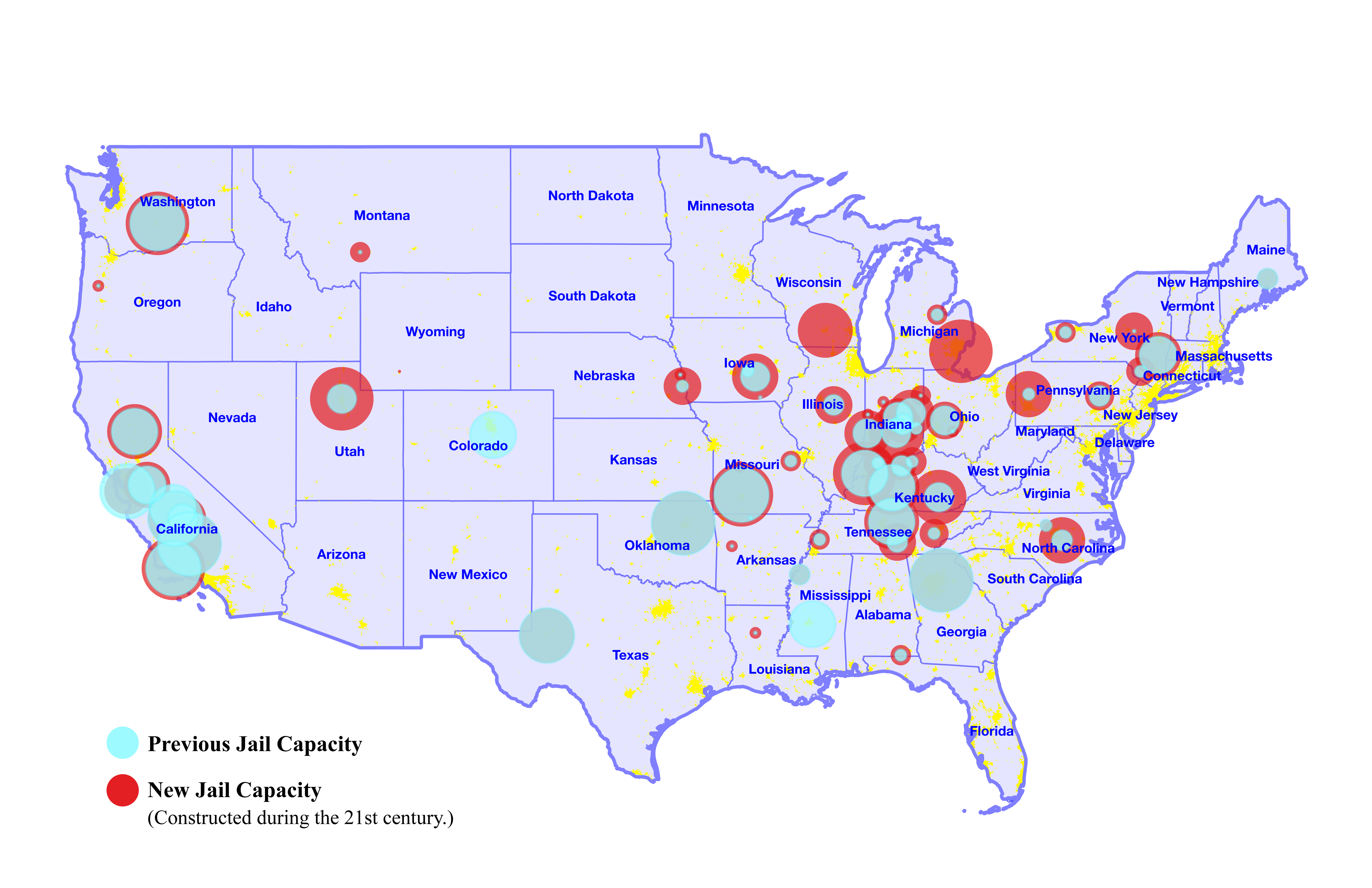

To unpack what the new “borough-based jails” typology means for the future of incarceration, a shift in exploratory scale is required to acknowledge the carceral condition across the United States. Pulling back to oversee the broader context, a clear urban/rural dichotomy is revealed. Carceral institutions are liquefying in the urban sphere, trading in the rigidity of cement walls and “out-of-sight” locations for glass skyscrapers that neatly fold into the city’s urban fabric. Simultaneously, these infrastructures are heavily solidifying in rural contexts, rendered visible by an ongoing and sharp increase in nonurban jail construction and detainment capacities.

De Blasio’s sleight of hand—his declaration that “the era of mass incarceration is over”—relies on the existence of a much larger machine. This machine, the Carceral Industrial Complex, must carefully balance questions of center and periphery, prison and community, humanity and inhumanity, and expansion and contraction to continuously weave the aura of imprisonment’s magic throughout its operations. By closing Rikers, introducing a new and “softened” carceral typology throughout the city, and simultaneously expanding jail-bed construction in rural locations across the state, New York continues to expand its carceral net while maintaining its position as one of the most progressive states in the country. As Davis states, prison “relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism, and, increasingly global capitalism.”10 The current balancing act between urban and rural areas is critical to keeping political engagement and control just so without having to abolish capital systems of order, and, ultimately, oppression.

In focusing on the jail, which is locally funded and administered (and primarily holds those awaiting trial), rather than on the widely researched prison, which is state or federally run (and holds those convicted for a period of more than one year), we are able to observe the totality of injustice produced by the Carceral Industrial Complex from a unique standpoint. The typology of the jail—and its escalating pervasiveness at the urban and rural level—is inextricably tied to the social order and “form of society” orchestrated by the political image, one that restores the “aura” of the “imprisonment solution” while declaring it undone. The image that results from DeBlasio’s declaration eclipses, however, the deep exchange between urban and rural carceral forces that require the continuation of imprisonment to uphold structures of oppression, crucial to which are the proliferation of the police and the existence of the “precriminal” identity. In order to understand what leads to the expansion of the carceral net and the dangers in equating what is “modern” to what is “humane” within architecture discourse, we must acknowledge the complex and inter-scalar web of relations that tie and necessitate carceral infrastructure to secure continued belief in social order as absolute panacea.

Liquefying in the Urban Sphere: Carceral Humanism

In March 1930, the New York Times declared Rikers “the most modern institution of its kind in the country.”11 The article celebrated Sloan and Robertson, the firm responsible for the design of Rikers, for its use of light-colored bricks “to avoid somberness of old-time penitentiaries” and of collapsible furniture to optimize the “more than six feet wide, seven feet long” cells, and for their addition of a “complete examination clinic with psychiatrist, neurological and medical facilities.”12 A month later, the Times followed up with another story praising the heating and ventilation system as one “different from any that has heretofore been installed in prisons”; a technology, the architects claimed, that would furnish “even temperature to all parts of the buildings.”13 Revisiting these articles written in the early twentieth century strikes a chord with how the “borough-based jails” are being portrayed today and highlights the unwavering seductiveness of linking modernness to technological “progress.”14 The cycle of architectural reform is highly complicit in allowing centuries-old violence of racism, segregation, and capital extraction to persist in the name of modernity.

The once “humane and modern” jail island has in recent years been condemned by several officials, including former Manhattan US Attorney Preet Bharara who deemed Rikers Island “a broken institution.”15 After years of standing in opposition to its closure—claiming how “unrealistic” and “impractical” it would be—De Blasio finally came around. The report Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island, published by the Office of the Mayor, committed the city to reducing the daily jail population to five thousand persons.16 As Dylan Rodríguez diligently dissects, these changes of heart often coincide with climactic moments of social reckoning, and they do so in order to normalize policing as something that “can be magically transformed into a non-anti-Black, non-racial-colonial (‘racist’) system.”17 In framing the conversation between the “inhumanity” of a dilapidated detention complex and the “humanity” of a modern “justice” complex, we find ourselves trapped again in a Sisyphean pursuit of purgatorial amelioration. Ruth Wilson Gilmore captures the detriments of this amelioration cycle and ties it to an obsession with “innocence” as a way to “correct” the ills of the carceral state: “Indeed, for abolition, to insist on innocence is to surrender politically because ‘innocence’ evades a problem abolition is compelled to confront: how to diminish and remedy harm as against finding better forms of punishment.”18 Reforming New York City’s jail system is part of what Rodríguez calls “white magic”: problem “solving” by means of piecemeal changes that protect the current system from total collapse, a system that continues to produce “asymmetrical misery, suffering, premature death, and violent life conditions for certain people and places.”19

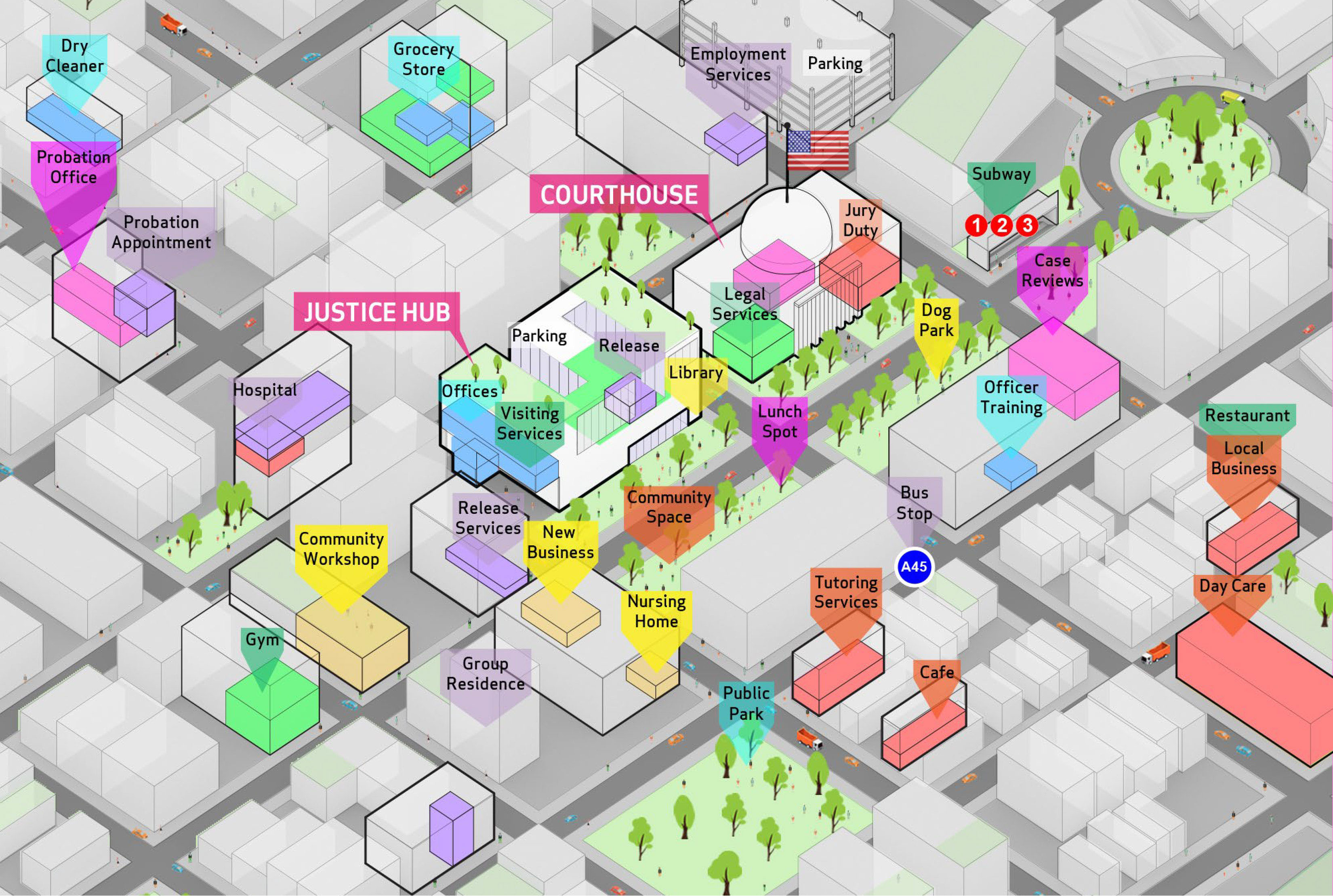

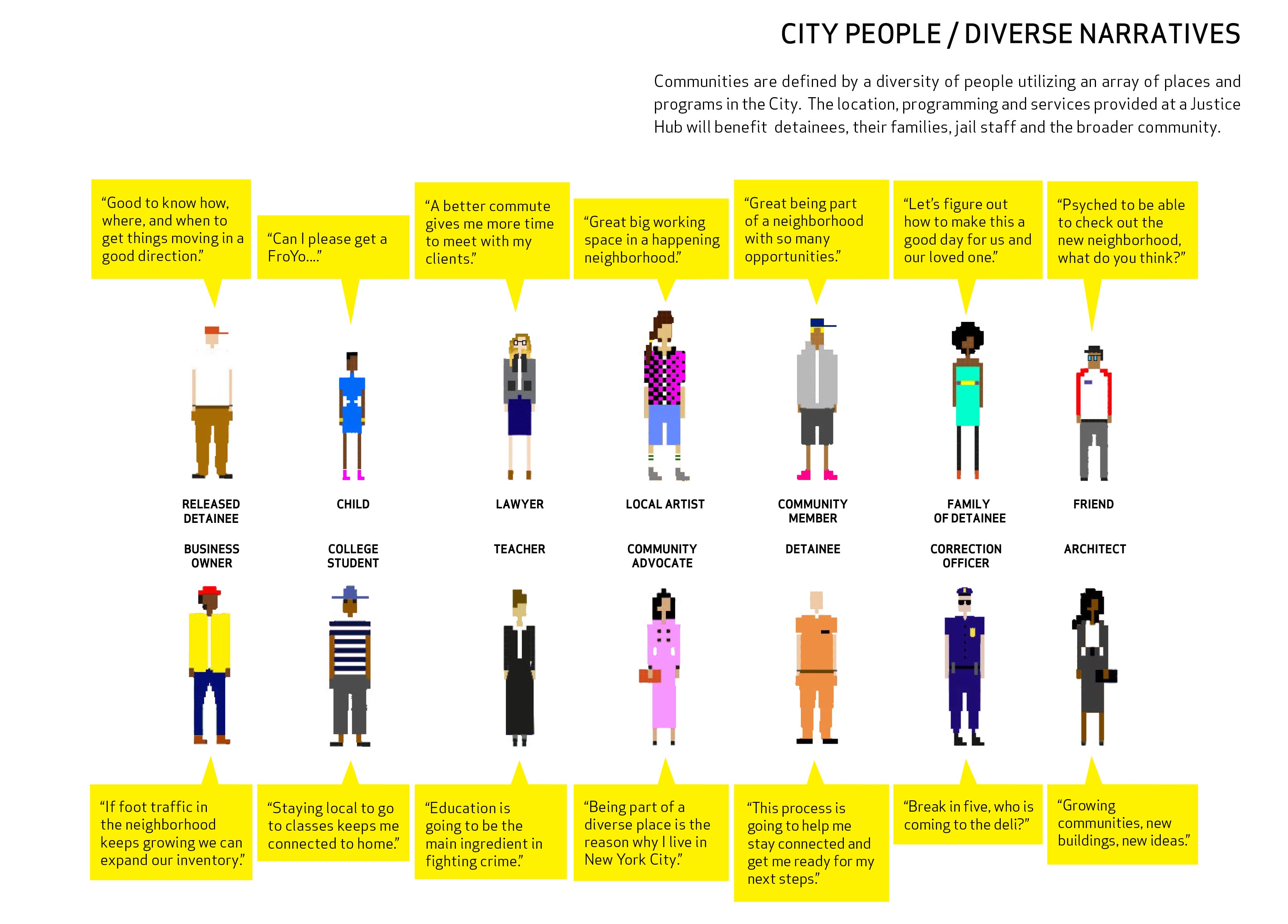

As part of reform’s magic, the urgency of abolishing the Carceral Industrial Complex continues to be deliberately obfuscated by visualizations produced for political convenience, depicting new and “reformed” jails as “humane” institutions. Responding to a request from the Lippman Commission to develop “healthier and more rehabilitative jail infrastructure,” the Van Alen Institute published a report called Justice in Design in 2017.20 The report proposes “justice hubs”—an interpretation of the rebranded “borough-based jail” model based on a series of workshops with groups directly affected by incarceration, seamlessly flowing in and out of surrounding community infrastructures. Presenting “bettered” systems in a graphically “approachable” manner, as James Kilgore reminds, merely continues to “rearrange the relationship of things and of people” and exposes the application of these typologies as modes of “cosmetic reform in order to avoid systemic restructuring.”21 The polemics behind Justice in Design’s diagrams, a collection of generalized and vague massings produced by architecture firm NADAA, were critically assessed during a conversation between Jarrod Shanahan, Zhandarka Kurti, and Brinley Froelich, published by Verso on March 13, 2020:

[The Justice in Design report] created these utopic jail designs as a public relations tool for expanding the city’s jail system. It’s a fairly surreal document—a glossy Ikea-looking pamphlet… Beyond the spectacle, however, it is a serious and wholly radical political document which argues that jails are “sites of civic unity” and should be integrated completely into communities.22

Evaluating architecture’s attempt at “#drawingincarceration,” Leah Meisterlin poignantly highlights that “the drawings do not function analytically or describe the geography of corrections practices, its concomitant logistics, uneven spatial burdens, and diversity of impacts… This strategy visualizes promises without complication and, as such, resembles advertisement over analysis.”23 This graphic sensibility is not a mistake or missed opportunity for the Justice in Design team; it is carefully conceived to allow for an “ethical slipknot,” as Meisterlin observes, which releases these designers from the responsibility of genuinely addressing the issue of incarceration. These graphics succeed in promoting an image of care that centers “carceral humanism” as the spatial solution. Introduced by Kilgore, the term “carceral humanism” refers to the dangers of portraying carceral iterations as “humane.” Kilgore states that it is through this form of carceral “repackaging” that jailers are recast “as caring social service providers.”24 It is crucial now to stretch the term “carceral humanism” to not only encompass programmatic mergers but address how carceral structures are seeping into the urban sphere and dissolving their architectural aesthetics into the surrounding community. By understanding “carceral humanism” as a spatial trend that “betters” the architectures of captivity, the term offers an architectural framework that exposes the consequences of reformist proposals. What Kilgore coins “repackaging” translates to the innate reformative appeal of the prison and its technocratic capacities long ago unraveled by Foucault.25

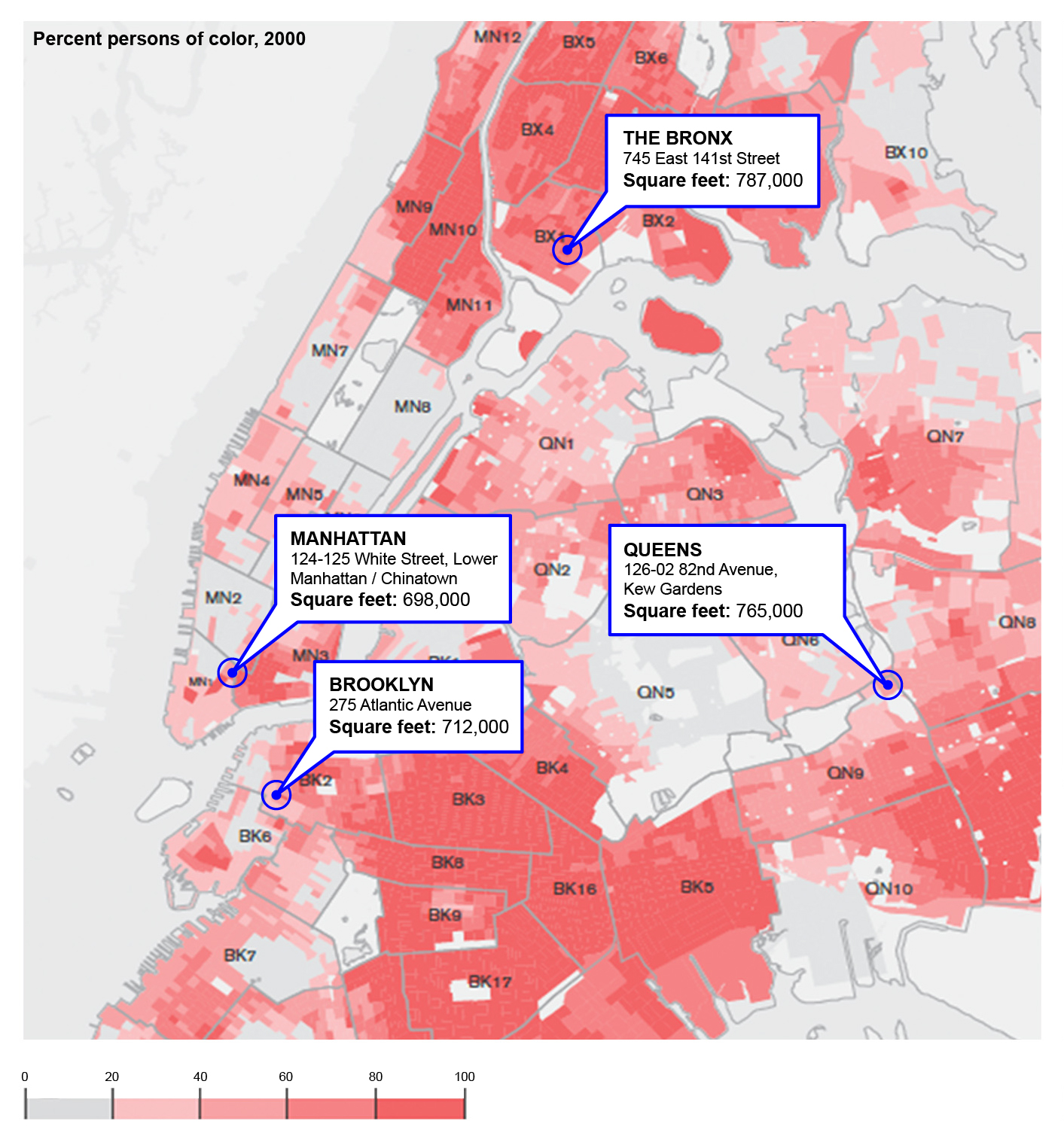

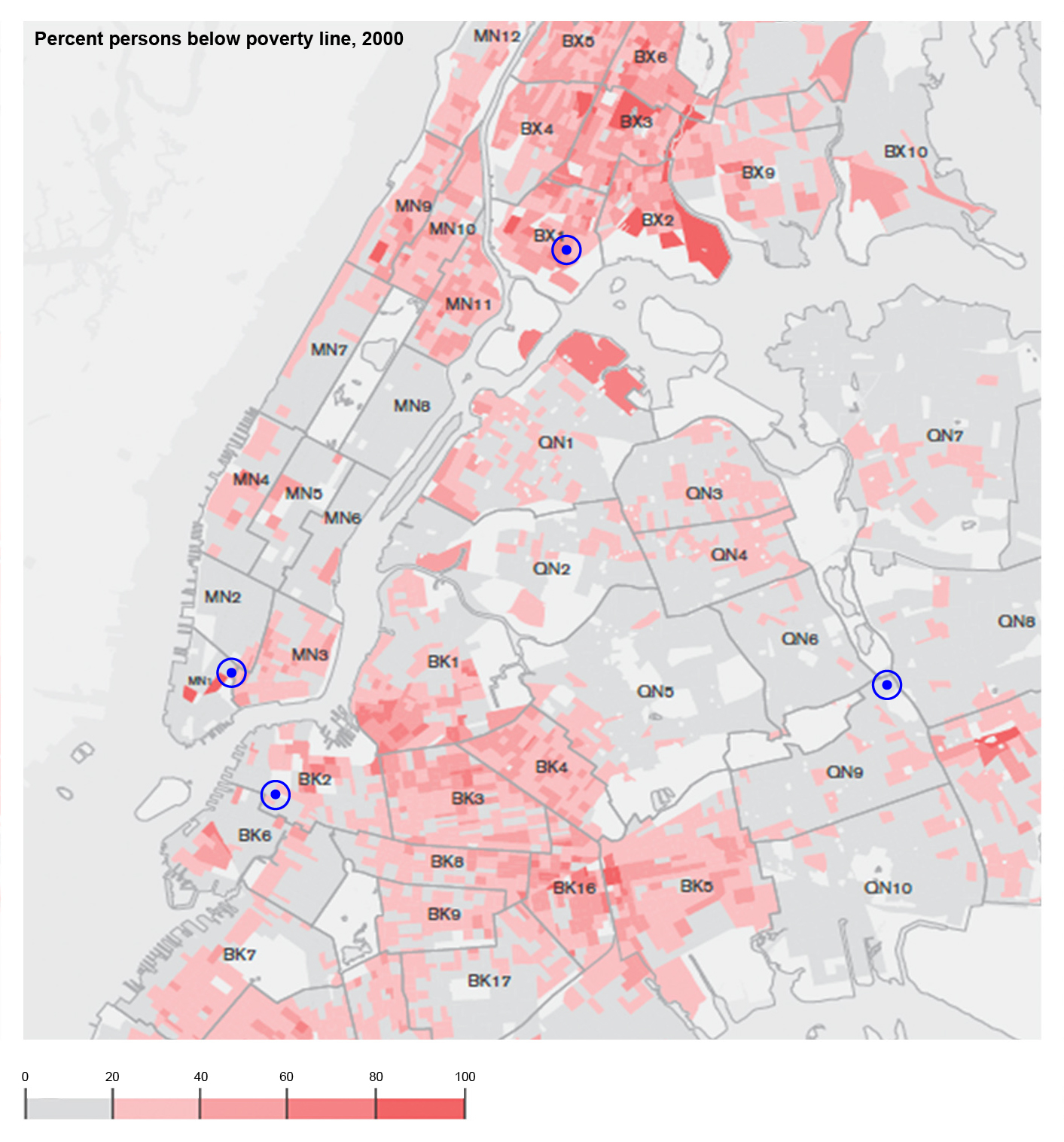

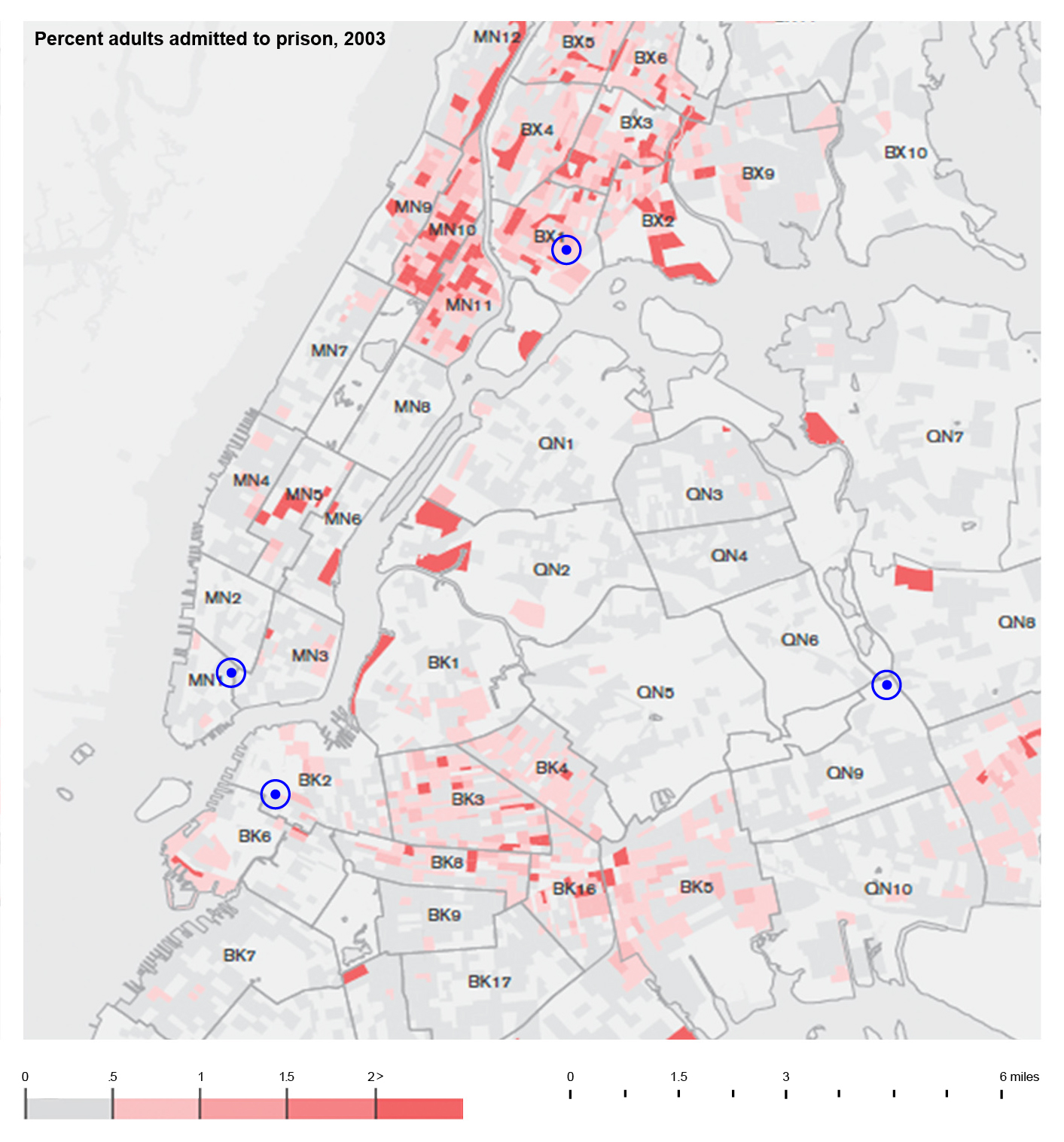

Since 2005, the Center for Spatial Research (CSR) led by Laura Kurgan has delved into analyzing incarceration geographies in the United States. Aside from the CSR’s Million Dollar Blocks project—which revealed that certain states were spending upward of a million dollars to incarcerate residents of a single city block—their research has more broadly uncovered a geographic pattern of convergence between the highest densities of people living below the poverty line, people of color, and people admitted to prison.26 Zooming in on one block in the South Bronx, the study revealed that in 2003, 11.11 percent of the people admitted to New York City’s prisons were residents of Community District 1. The particular block accounted for 5,109 residents, 79 percent of whom identified as Hispanic or Latinx, and 47 percent of whom were living in poverty.27 Although the study was carried out nearly a decade ago, these socioeconomic realities continue to intersect. A 2019 study showed that among New York City’s fifty-nine community districts, Community District 1 ranks fourth in the highest number of incarcerated residents, with an incarceration rate of more than 300 per 100,000 adults (aged 16 years or older).28 While Van Alen’s report and the CSR’s data-driven research both draw connections between the prison/jail and the city/community, their representational intent is entirely different—one proposes irresponsibly banal, yet incorporated, carceral futures, while the other attempts to visualize the root causes, and consequences, of our carceral present.

Overlaying the locations for the proposed “borough-based jails” onto the CSR’s socioeconomic maps gives new meaning to “borough-based.” By situating carceral infrastructure in dense and low-income communities of color, these jails will only serve to inflame concentrated geographical disadvantage.29 Not only will the novelty of these “modern” architectures camouflage their reality in representing a statistically probable future for surrounding populations, but their “bettered” nature will further dissolve the fine line that fights to separate community and carceral life. Visuals that portray incarceration’s utopic, community-oriented, future (such as those produced by NADAA) evince a new carceral trick. The disappearing act of the prison relies not on it being out of sight but right in front of our eyes, not on its contraction but on its proliferation of carceral control within certain communities. This is the magic of positioning.

Solidifying in the Rural Sphere: Carceral Expansion

California saw one of the biggest prison construction and population booms in response to the “law and order” rhetoric used throughout the twentieth century, as has been extensively researched by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Well into the twenty-first century, prison overcrowding, while not a new phenomenon, had become undeniable in the western state. After Brown v. Plata in 2011, the US Supreme Court ordered California to reduce its prison population to 137.5 percent of its design capacity. It had been operating at more than 200 percent.30 In order to achieve this, the state had to release around 46,000 incarcerated people.31 This mandate could have been a portal through which to imagine a future without the need to warehouse those abandoned by the state, to “imagine [the] world anew.”32 Yet, California’s governor Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 109, commonly referred to as “prison realignment,” which shifted “new non-violent, non-serious, and non-sexual offenders,” from state prisons to county jails. While prison populations decreased, prompting prison closures along the way, counties received funding from the state to expand their jail capacities, solidifying carceral presence in rural America. To understand what occurred in California is to grasp a nationwide trend in carceral logics, and the prowess of its reformative capacities. In New York state, since Governor Cuomo took office in 2011, twenty-four prisons and juvenile detention centers have closed.33 Meanwhile, New York state’s use of pretrial detention in jail increased by 52 percent across the state’s twenty-four rural counties.34 The seesaw of capital finds a way to magically disappear from some locations and rematerialize in others, balancing out the carefully calibrated scales.

After the prison boom of the late twentieth century, governing entities across the nation started applying pressure on local sheriff departments, mainly in rural areas, to spearhead the jail boom of the twenty-first century.35 In order for jails to expand at the rate at which they have, what is required is something Gilmore calls “organized abandonment,” which upholds the legitimacy of jailing and of maintaining “criminal” populations:

In the United States, where organized abandonment has happened throughout the country, in urban and rural contexts, for more than 40 years, we see that as people have lost the ability to keep their individual selves, their households, and their communities together with adequate income, clean water, reasonable air, reliable shelter, and transportation and communication infrastructure, as those things have gone away, what’s risen up in the crevices of this cracked foundation of security has been policing and prison.36

By establishing organized abandonment as the standard for most rural towns across the US, sparse moments of state and federal investment are thus regarded as unique opportunities. In the inconsistency of financial help from the state to rural towns, carceral structures are seen as a path toward financial stability. And here is imprisonment’s magic finale: to turn the need for security from “crime” into that of security from financial ruin, all the while applying the same architectural typology as solution. In a 2018 interview with Jack Norton, municipal court judge Howard Aison—of the deindustrialized, rural city of Amsterdam, New York—confessed to his role keeping the city solvent by any means necessary: “I made a lot of money for the city. And how did I make that money? Fines.” Aison calculated that the total revenue collected from the fines and fees he imposed while he was the only full-time judge between 1996 and 2015 amounted to $1,451,596, and when asked if this revenue had been beneficial to the city, he replied, “It’s a good thing… It’s expensive to have a police department.”37 Indeed, it is expensive to have a police department, which must sustain itself by either collecting fines or incarcerating those who cannot pay. This recipe of tail-chasing financial survival is one that not only scars rural community relationships but welds the ideological bonds that define policing for profit.

As incarcerated populations from state and federal prisons are rearranged into local jails, what is circulated and cultivated is a “fear,” of criminality and of poverty, which retracts social welfare as it cements “political organization around police and carceral power.”38 Jail expansion across rural America, in addition to requiring the presence of organized abandonment, is impossible without fear. Maintaining order requires the perpetuity of a threat. For the proliferation of the Carceral Industrial Complex that threat is the future criminal, or, to borrow Philip K. Dick’s term, the “precriminal.” While jail expansion is heavily incentivized by state and federal governments, there exists an underlying reality that might be even more significant: rural America (and most likely urban and suburban as well) holds on tightly to an unfounded belief in crime futurity.39 Most US jail facilities built in the twenty-first century are being designed for future expansion, even though these are already being built in excess of what is needed locally.40 New York City’s “borough-based jails” are no exception. Brooklynites protesting the new forty-story Brooklyn jail proposed for 275 Atlantic Avenue intuited this carceral-architectural prophecy, chanting: “If you build it, they will fill it.”

Alternative Futures

To begin the work of truly ending the “era of mass incarceration,” we must commit to thinking of carceral space “not as simply an edifice, as a place made up of walls and cells and mess halls,” but “as a set of relationships.”41 That the carceral is liquefying in urban environments as it is solidifying in rural communities is not mere coincidence; these carceral conditions are bound by a “set of relationships” whose interests rely on maintaining the magical illusion of imprisonment as the upholder of social order. This illusion, permeating through the choreographed scene of De Blasio’s announcement to close Rikers and open new jails, is what permits the physical construction of certain futures that advantage certain populations and disadvantage others. Believing in carceral humanism—and the dangerous slippage it materializes between detention and care services—is crucial to the “borough-based jails” proposal. But no matter how “humane,” these urban jails escalate a form of carceral slippage into cities—extending their grasp under the (also “magical”) premise of reform, through which superficial tweaks are made while “the procedures of criminalization [remain] ever hardening at the center.”42 Examples such as the coercive debt collection in Amsterdam, New York, and the larger prison realignment campaigns driving jail construction nationwide reveal that rural jails are expanding capacities in communities that express fear of financial stability rather than of crime, yet hold a continued belief in crime futurity. Evaluating the city’s plan alongside the rural condition and the socioeconomic geographies within New York City itself, many of the same methods of tactful obfuscation apply, be it of the root causes of mass incarceration or of the dangers of reformism. Across the geographical spectrum of the US, racially insurgent social life that diverts from capital’s prescribed order continues to meet new iterations of oppression by means of (pre)criminalization.

Greek mythology’s serpent monster, Hydra, has many heads, and it is said that when one is cut off, two more grow back in its place. De Blasio sets out to cut off one of Hydra’s heads; four more will now grow back in its place. Even more, the shuttered-to-be-replaced Rikers will not only spawn new heads locally but will proliferate itself statewide—indirectly triggering a higher carceral concentration in rural peripheries, toward which the eyes of activists, media, and scholarship are not yet so eagerly directed. In addressing the ordering structure of organized abandonment embodied through the jail, the exposure of the US’s dependence on crime futurity holds the potential to dismantle the grasp of the Carceral Industrial Complex.

New York City has announced that COVID-19 budget constraints will likely set back its plan to close Rikers, pushing the city’s 2026 deadline back by two years. With the wave of social reckoning sweeping across the United States (if not globally), we are at a point where what is currently a deferred carceral future can be brought to a halt once and for all. The set of relationships that uphold these carceral and oppressive systems require strategic and radical transformation, not to be confused with “reform.” Behind reform’s magic, which is the magic of incarceration, of the political image, and of “modern” architecture, lies a portal through which the opportunity to refuse racial violence and celebrate racial equality becomes possible. In order to access this portal, we must critically confront the spatial terms of political order that ensure the proliferation of the carceral state, addressing not just what is occurring in urban environments but also in rural environments, not just at the center but in the periphery, not just in the present but in the past and future. If the construction of jail beds enables the transformation from precriminal to “criminal,” their deconstruction and abolition can, and will, threaten the existing order of things, and, by so doing, we will consciously open portals toward alternative futures.

-

Cedric J. Robinson and Erica R. Edwards, The Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 7. ↩

-

Mayor Bill de Blasio @NYCMayor, Twitter post, October 25, 2019, link. ↩

-

“Dignified design” is a term used among correctional architecture practices to project “humanity” through adequate access to sunlight and open space. ↩

-

Robinson, The Terms of Order, 38. ↩

-

Originally purchased by a Dutch settler in 1664, Rikers Island was sold by his descendants in 1884 to the Commission of Charities and Corrections for $180,000 ($4,758,997.96 today). ↩

-

Avery F. Gordon, “Globalism and the Prison Industrial Complex: An Interview with Angela Davis,” Race & Class 40, no. 2–3 (March 1999): 147. ↩

-

“DOC in Transition,” City of New York Department of Correction, link. ↩

-

Originally around 90 acres, the island that is now Rikers Island was expanded to 415 acres in the early twentieth century. It should be noted that the first stages of this expansion used convict labor to haul ashes for landfill. Raven Rakia, “A Sinking Jail: The Environmental Disaster that Is Rikers Island,” Grist, March 15, 2016, link. ↩

-

The “lesser evil,” as unpacked by Eyal Weizman, is “a dilemma between two or more bad choices in situations where available options are, or seem to be, limited. The choice made justifies the pursuit of harmful actions that would otherwise be deemed unacceptable in the hope of averting even greater suffering.” See Eyal Weizman, The Least of All Possible Evils: A Short History of Humanitarian Violence (London: Verso, 2017), 6. ↩

-

Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011), 16. ↩

-

“File Plans for Unit of $8,000,000 Prison,” New York Times, March 14, 1930, link. ↩

-

“File Plans for Unit of $8,000,000 Prison,” New York Times, link. ↩

-

“Push Prison Work to Aid Unemployment,” New York Times, April 3, 1930. ↩

-

NYC Department of Design and Construction, “Design Principles and Guidelines: Manhattan Detention Facility,” A Roadmap to Closing Rikers, October 5, 2020, link. ↩

-

See Benjamin Weiser and Michael Schwirtz, “US Inquiry Finds a ‘Culture of Violence’ Against Teenage Inmates at Rikers Island,” New York Times, August 4, 2014, link. ↩

-

At its peak in 1991, Rikers held 21,674 incarcerated persons during the so-called crack epidemic, which, in reality, caused a swell in arrests of Black Americans due to Congress’s racialized drug laws including the 100-to-1 sentencing disparity for crack compared to powder cocaine and, specifically for New York, the Rockefeller Drug Laws. See also “Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island,” NYC Office of the Mayor, 2017, link. ↩

-

Dylan Rodríguez, “The Magical Thinking of Reformism,” LEVEL, October 20, 2020, link. ↩

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence,” in Futures of Black Radicalism, eds. Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin (London: Verso, 2017), 236. ↩

-

Van Alen Institute and the Independent Commission for New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, Justice in Design: Toward a Healthier and More Just New York Jail System, July 13, 2017, link. ↩

-

James Kilgore, “Repackaging Mass Incarceration,” CounterPunch, June 6, 2014, link. ↩

-

Zhandarka Kurti, Brinley Froelich, and Jarrod Shanahan, “From New York to Salt Lake City, There’s No Such Thing as a Nice Prison,” Verso Blog, March 13, 2020, link. ↩

-

Leah Meisterlin, “Not Yet #AfterRikers: Looking for #JusticeInDesign,” The Avery Review 32 (May 2018), link. ↩

-

In an interview, Michel Foucault clarifies his stance on prison “reform”: “What we have to denounce is not so much the ‘human’ side of life in prison but rather their real social function—that is, to serve as the instrument that creates a criminal milieu that the ruling classes can control.” See Roger-Pol Droit and Michel Foucault, “Michel Foucault on the Role of Prisons,” New York Times, August 5, 1975, link. ↩

-

Spatial Information Design Lab, The Pattern (New York: Columbia University GSAPP, 2008), link. ↩

-

In 2003, $570,000 was allocated to incarcerate people that had previously resided in that one block. See Spatial Information Design Lab, The Pattern, 39. ↩

-

In Community District 1 in the South Bronx, 39.6 percent of residents live below the poverty line, 68 percent identify as Hispanic or Latinx, and 28 percent identify as Black. ↩

-

Robert J. Sampson describes “concentrated disadvantage” as the cumulative effects of disadvantageous socioeconomic factors, linked to race and poverty, that influence the state of a particular neighborhood, community, or geographic space. Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Felton Earls, “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy,” Science 277, no. 5,328 (August 1997): 918–924. ↩

-

Adam Liptak, “Justices, 5-4, Tell California to Cut Prisoner Population,” New York Times, May 23, 2011, link. ↩

-

William J. Newman and Charles L. Scott, “Brown v. Plata: Prison Overcrowding in California,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 40, no. 4 (December 2012): 547–552. ↩

-

Reminiscent of the portal Arundhati Roy is suggesting we seek amid the COVID-19 pandemic. See Arundhati Roy, “The Pandemic Is a Portal,” Financial Times, April 3, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Governor Cuomo Announces Closure of Additional Prisons Following Record Declines in Incarceration and Crime Rates,” New York State, February 15, 2019, link. ↩

-

The use of pretrial detention in New York jails was already rising since 2000. See “Incarceration Trends in New York,” Vera Institute of Justice, 2019, link. ↩

-

The reasons behind rural jail expansion have been narrowed down by the Vera Institute of Justice: “one, systemically fewer resources that discourage the use of detention alternatives; and two, increasing financial incentives that, conversely, encourage expanded jail capacity.” See Jacob Kang-Brown and Ram Subramaniann, “Out of Sight: The Growth of Jails in Rural America,” Vera Institute of Justice, June 2017, link. ↩

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Chenjerai Kumanyika, “Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition,” June 10, 2020, Intercepted, podcast, link. ↩

-

Jack Norton, “No One Is Watching: Jail in Upstate New York,” Vera Institute of Justice, April 19, 2018, link. ↩

-

Brett Story, Prison Land: Mapping Carceral Power Across Neoliberal America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 103. ↩

-

Vera’s report states, “Nationwide, crime rates are down in all offense categories… Moreover, crime rates are substantially lower in rural versus urban counties. Rural counties have proper crime rates that are three-quarters, and violent crime rates that are two-thirds, that of urban areas.” See Kang-Brown and Subramaniann, “Out of Sight,” 17. ↩

-

Kang-Brown and Subramaniann, “Out of Sight,” 21. ↩

-

Story, Prison Land, 9. ↩

-

Gilmore, “Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence,” 228. ↩

Tamara Zeina Jamil is an architectural designer and researcher. Currently, she works at Forensic Architecture in London. Her personal work explores the geopolitics of incarceration, specifically the relationship between urban and rural jail expansion. She holds an MA from the Center for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, and a BArch from Cornell University.