The Mediterranean: historian Fernand Braudel sought there the keys to the genesis of capitalism, some looked more prosaically for design inspiration (modernism notably, and what Barry Bergdoll coined “Mediterraneanism”), and others simply looked for answers.1 A plethora of contemporary publications compile works that engage with the harbor-cities and coastal territories unified by a common shore.2 With a sustained interest in investigating cities along the coast from Beirut to Alexandria, I, too, belong to this cohort, circling around and back to my hometown of Marseille, feeding an unshakable fascination with urbanized areas around Mare Nostrum for over a decade.3 Interconnectivity, mercantilism, patterns of urbanization and gentrification, exploited bodies, murderous migration routes, hard and fleeting borders, religious and cultural identities, grands projets (i.e., the inevitable Atlantropa, the Suez Canal, Europe), architectural styles, colonial histories, classic origins, climate change and rising waters, bankrupt states and corrupt governments, post and neo-colonial wars and ensuing exodus, speculative coastal developments: there is a petri dish of disparate topics projected onto this thing called “the Mediterranean.”

For spatial disciplines, the Mediterranean and its topography offer possible routes toward an understanding of the world’s complexity, from geography to architecture. Its graspable size and cultural variety but also its hyper-relevance vis-a-vis migration flows, climate emergency, and violent conflicts make it a laboratory of sorts, encapsulating within its territorial compactness everything that matters. The unifying waterbody appears to present anyone who asks with universal answers to very locally grounded questions; and the other way round, with insular answers to collective problems. And this is precisely what the first four small books published by kyklàda.press attempt to do—with varying degrees of success. kyklàda.press is a self-described “small imprint, a series of texts resonating with phenomena in the Aegean Archipelago.” Based in Athens, where it was founded in 2020 by architects and visual artists David Bergé, Juan Duque, Dimitra Kondylatou, and Nicolas Lakiotakis, it has since published six volumes: The Sleeping Hermaphrodite: Waking Up from a Lethargic Confinement; Public Health in Crisis: Confined in the Aegean Archipelago; Free Love, Paid Love: Expressions of Affection in Mykonos; The Architect Is Absent: Approaching the Cycladic Holiday House; Architectures of Healing: Cure through Sleep, Touch, and Travel; and (Forced) Movement: Across the Aegean Archipelago, of which the first four are reviewed here.4 Each volume compiles texts of various lengths around a topic, accompanied by a centerfold of photographs or iconographic archival material, which function like an essay in their own right. Compact and pocket-sized, the books feel unpretentious, practicable, and unfussy (four of them made it from the Ligurian Coast across to the shores of Massachusetts in my handbag). Yet their content is rich and complex.

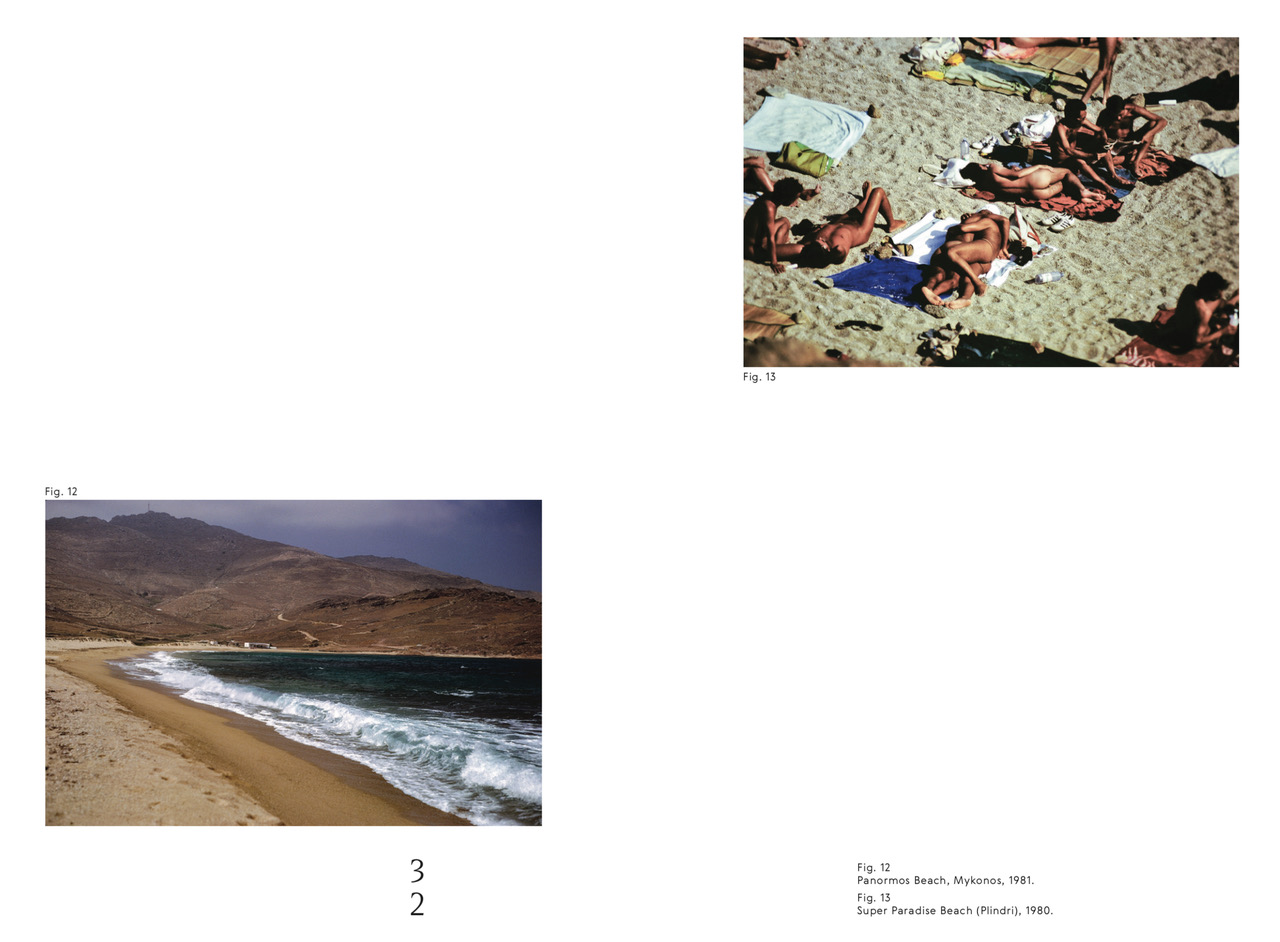

Intimate stories of promiscuity and queer erotica around the islands of Mykonos and its lesser-known neighbor Delos anchor Free Love, Paid Love: Expressions of Affection in Mykonos by Juan Duque, Nicolas Lakiotakis, and Dimitra Kondylatou. In the piece “Transactions of Love,” Lakiotakis tightly connects the archipelago’s topographic and territorial status to its political economy, tying its freedom to its fiscal autonomy, its sexual diversity to its criminal past—all with a wink to Braudel.5 In the essay “To Watch every Sunset as if it was the Last One,” Juan Duque hints at a possible conflation between contemporary sex work and the islands’ commodification, mapped through the banality of YouTube comments, that bridges the specificities of the isolated Greek archipelago to the world. However, the author’s refusal to particularize the islands’ current urbanization leaves readers to speculate as to whether these political problems are so distinctive from those faced by so many other places, where tourism and gentrification have irremediably destroyed lifestyles and landscapes. Does Free Love, Paid Love’s claim of an insular uniqueness and extirpated special status for Cycladic culture stand?

The volume’s ensuing ping-pong between “pseudo-encyclopedic definitions of love” and excerpts from poems by the Greece-obsessed Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, the formerly enslaved Bostonian Phillis Wheatley, the eleventh century Persian poet Omar Kayyam, Shakespeare, and Oscar Wilde forms an improbable assemblage in service of the argument that love is not a universal concept, nor can its many forms be contained in that single word. Yet the plea to look back into an undifferentiated, “Mediterranean Antiquity” to understand such complexities contradicts these poetic references. And another lack of distinction resonates even more strongly in the last piece by Kondylatou. “Professional Hugs” is a powerfully intimate evocation of a young and broken-hearted tourist‚ someone who could be anywhere, anytime.

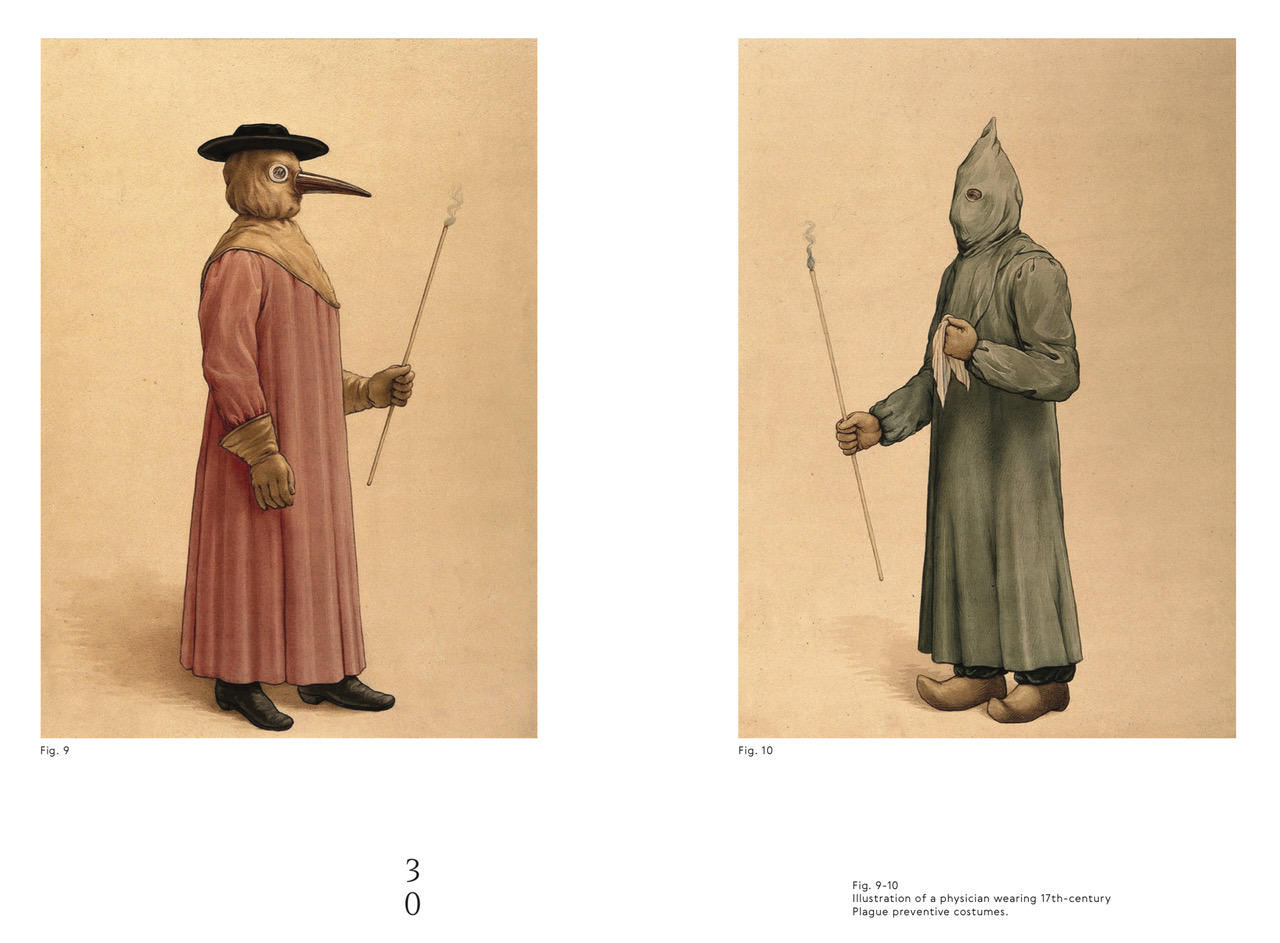

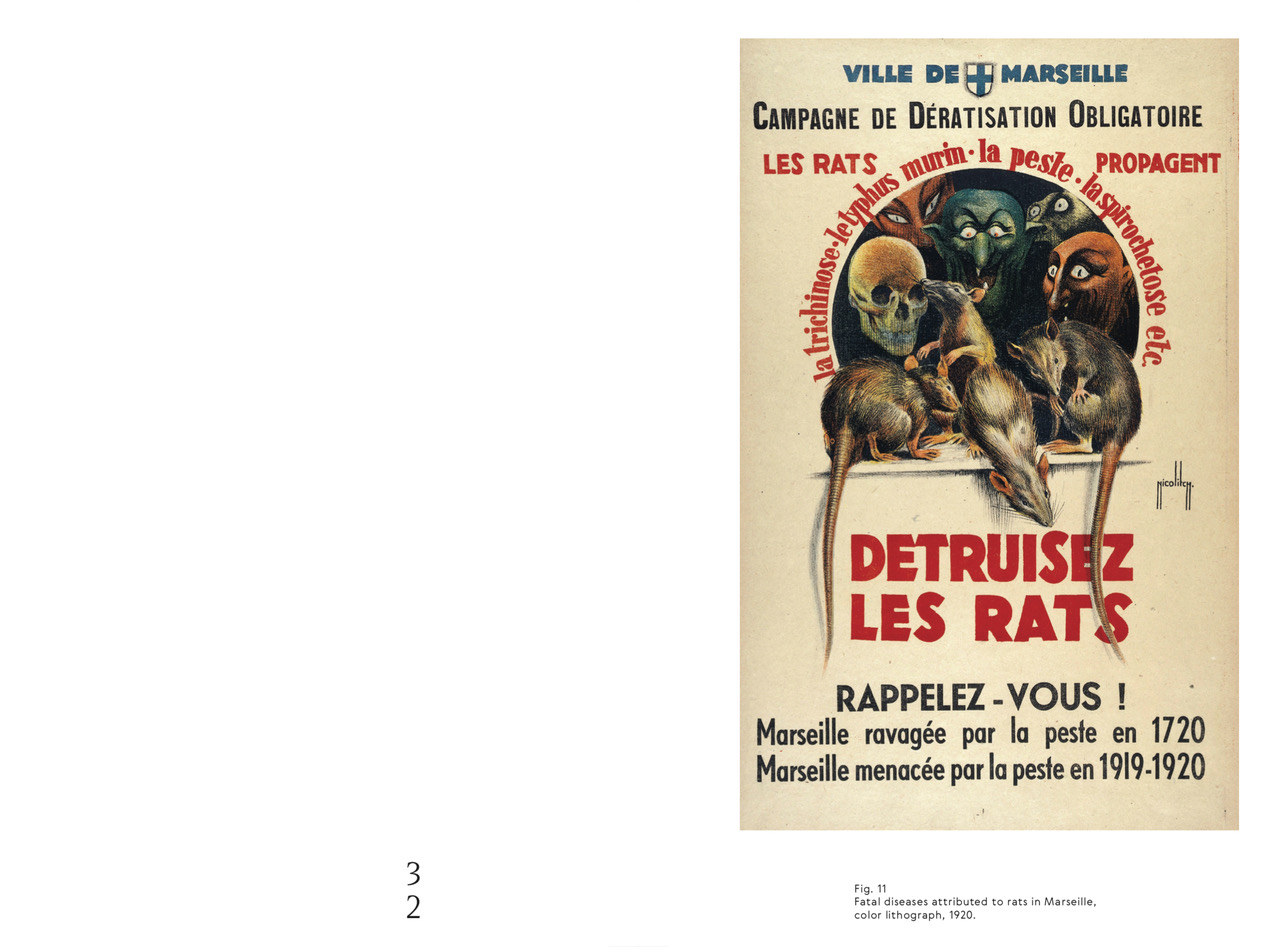

With even more pretensions to the universal is Public Health in Crisis (despite its geo-located subtitle Confined in the Aegean Archipelago). Made up of contributions by Dimitra Kondylatou, Nicolas Lakiotakis, and Hulya Ertas, the volume responds to the global health crisis and the ensuing planetary anxiety that gripped the world in early 2020. In lieu of a preface, the book begins with a list of COVID-19–ridden luxury cruise ships left at sea with their sick and their dead, which no harbor wanted to receive—eerily reminiscent of the plight of the Aquarius, Open Arms, and Ocean Viking humanitarian ships stranded at sea for weeks as Mediterranean ports refused one after the other to let them dock in 2018 and 2019.6 The tables had turned for the Diamond Princess and other tackily named cruise ships, summoning the very opposite of the luxurious mirages these infrastructures of leisure were designed to conjure. Instead, the public imagination was filled with horrendous visions of the Flying Dutchman and other plagued boats à la derive, apparitions that resonate with the terrifying physicians roaming the streets of ravaged Marseille in 1720 depicted in the books’ centerfold. As the coronavirus-hit Costa Luminosa docked in Marseille to unload its sick passengers, it summoned the Grand Saint-Antoine, which brought death and ruin to that very city four centuries ago—the disease’s entry-point on its way to devastating the whole of Europe.

It is, perhaps inevitably, with this persistent human trauma of the plague that the volume unfolds, exploring viral epidemics and prophylactic architectures alike. The fascinating account of lazarettos and their carceral typologies, with spatial solutions to separate and enclose, climaxes with the particular case of Syros. The island—itself an enclosed nature and ideal stage for a coercive architecture at the service of both public health and mercantilism—is an ideal backdrop for this discussion of insularity. Supported by excellent images, as the volume oscillates between modern and ancient history in its demonstration of epidemics’ cyclical nature, it lays bare the fragility of human life and futile claims of progress and modernity: the scientific and industrial world we live in will not, and cannot, save us.

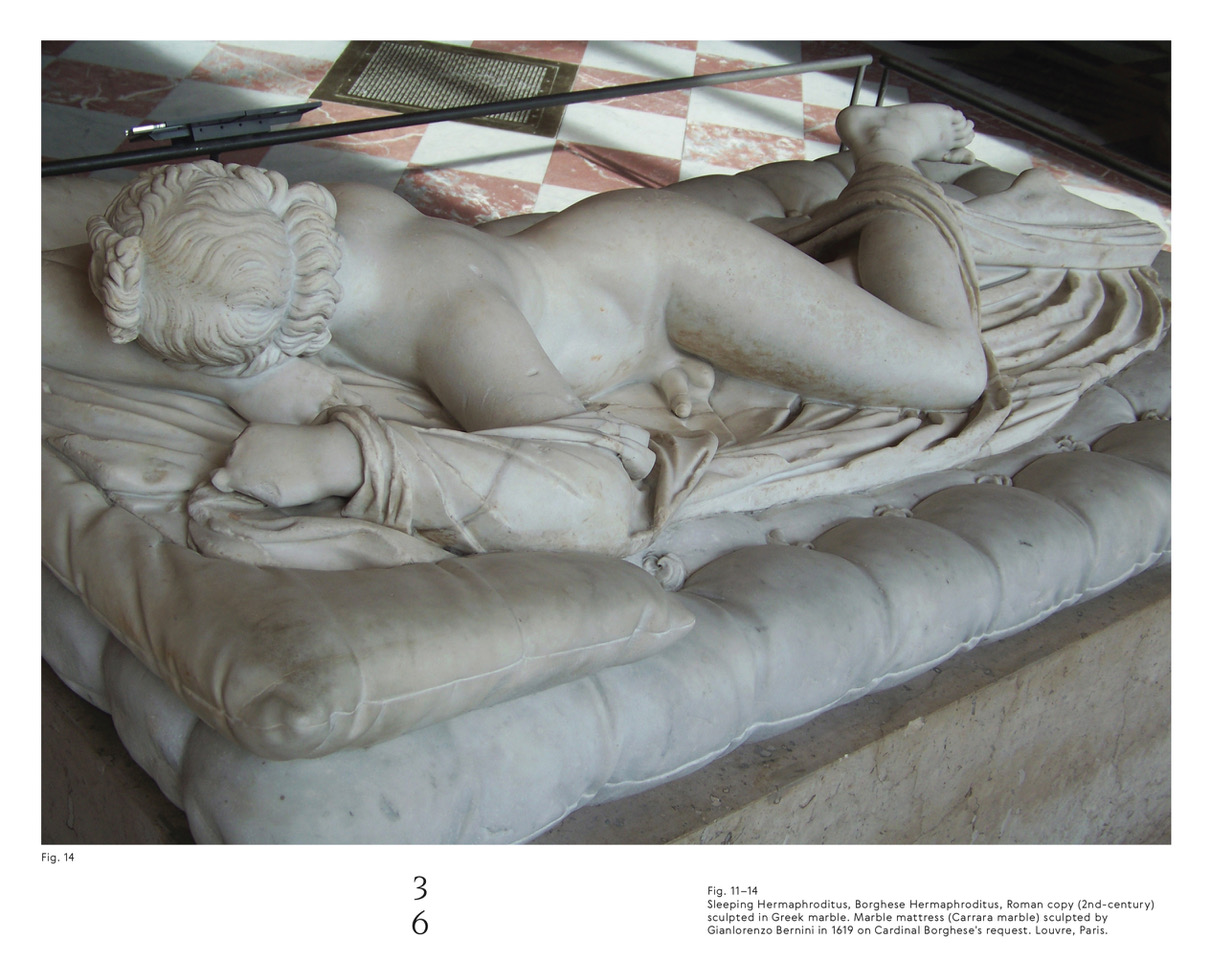

Confronting gender as another constructed conundrum of modernity, The Sleeping Hermaphrodite: Waking Up from a Lethargic Confinement (by Juan Duque, Nicolas Lakiotakis, Denis Maksimov, and Paul B. Preciado) addresses itself to Bernini’s fluid, reclining marble statue, opening with a short, compelling diary entry by Paul B. Preciado, “My Trans Body Is an Empty House.” Further, drawing from the ancient text “The Theogony” that contains important positions on gender roles within its hidden modernity, Denis Maksimov convincingly argues that Athena and Dionysus are divine queer figures, asexual and pansexual respectively, and establishes mythology as a useful tool in the fight against patriarchal political systems. This spectacular and welcome start allows for an enriching dialogue that reaches beyond the restrictive reading of particularity versus universalism. It sets the stage for the hermaphrodite figure, a nonbinary mythical creature treated with a slightly obsessive exploration not very different from that of Fernando González Ochoa, author of the eponymous book mentioned later in the volume.7

Hermaphroditus is documented in its numerous iterations, with images showing the sculpted figure leaning down under the weight of gravity, its mineral materiality and reclining position literally grounded in the “horizontality of the Earth.”8 Stunning unfinished statues emerging from Naxos’s rocky topography provide the Cycladic association—a somewhat fragile link. While an enlightening dive into how Greek Antiquity may shed new light on the construction of gender, the essay “The Sleeping Hermaphroditus Roman type” by Juan Duque also reaches a paradoxical conclusion. Despite being a glorified figure with divine birth origins, the hermaphrodite was negatively perceived in these ancient societies. This seeming contradiction between that which is revered in art and disdained in society is an observation that would benefit from consideration alongside external references such as First Nations’ Two Spirits or Third Gender-Hijras, to better understand the role of gender nonconformity in resistance against colonialism, racism, and other forms of oppression. Perhaps the tension between classical themes and current discussions could be used to explore other paths, for instance to reflect on the role Ancient Greek culture and its marbles plays in the European, white, heteronormative, colonial project—an observation that would be useful in the last volume reviewed here, by Hulya Ertas, Mâkhi Xenakis, Sharon Kanach, David Bergé, Dimitra Kondylatou, and Sven Sterken.

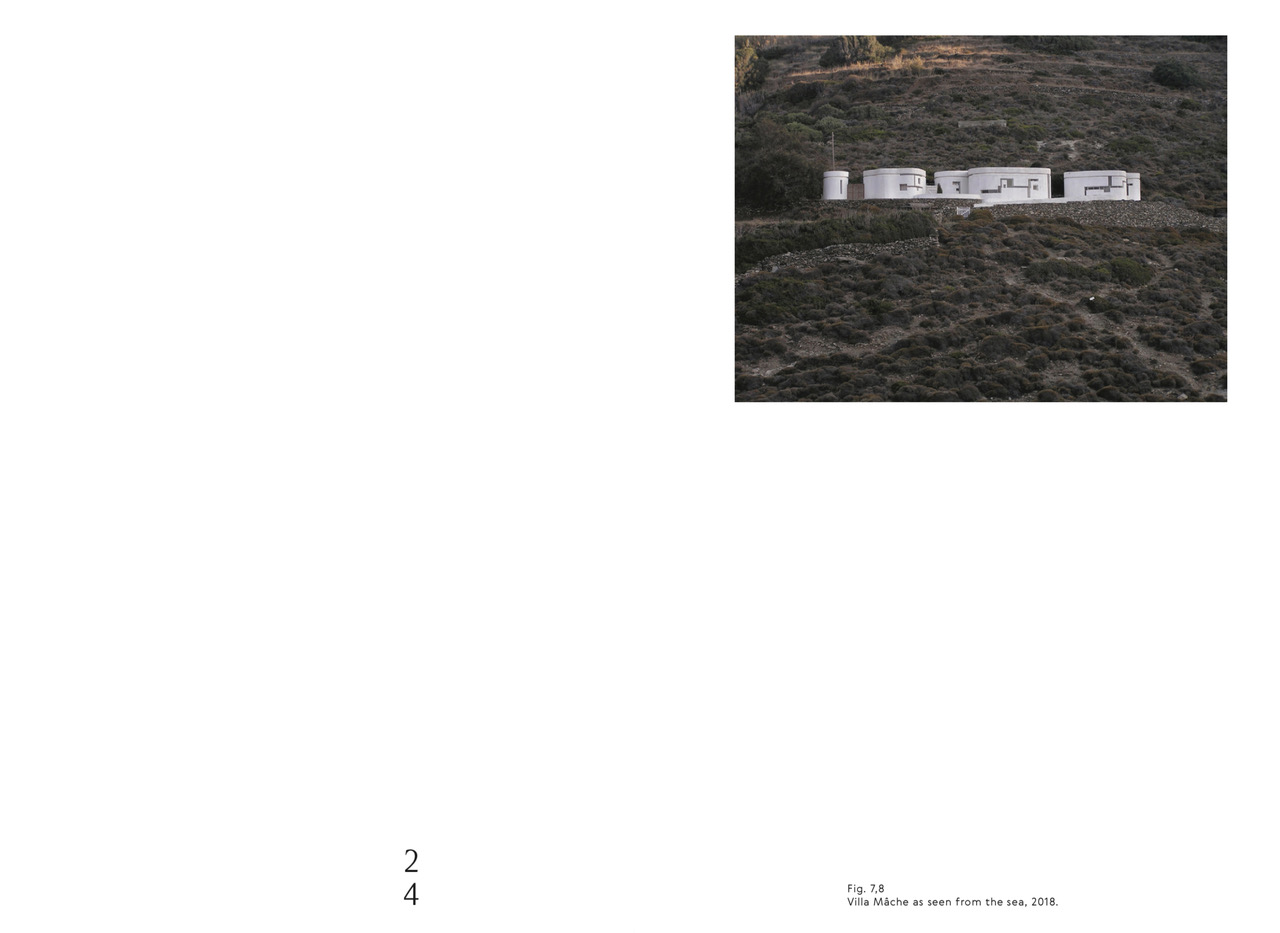

Despite what The Architect Is Absent: Approaching the Cycladic Holiday House claims, Iannis Xenakis, the architect, is very much present. And so is the house he designed, the Villa Maché. It is true that the multitalented, estranged disciple of Le Corbusier designed a vacation house for wealthy friends on the remote Cycladic island of Amorgos without once setting foot there, instead delegating construction to younger colleagues and local craftsmen.9 While Kondylatou’s argument revolves around celebrating Villa Maché as a paradigmatic example of the merger of authored modernism and what is identified as anonymous “vernacular Cycladic architecture,” it is the more general attempt to deconstruct the narrative of whitewashed Aegean buildings as an essential aesthetic element of modernism that is the most convincing, with Corbusier’s grand tour and the CIAM cruises providing persuasively weighty evidence.10

By problematizing the appropriation of modest yet contrived contextual characteristics into universal principles, Kondylatou uncovers how a series of actors, from CIAM participants to local architects and the Greek National Tourism Association, embraced modernism—establishing a continuous legacy from the white walls of the Aegean back to the marbles of Antiquity, claiming universalism, modesty, purity, and authenticity. Nonetheless, grounding the birth of modernism immediately adjacent to the so-called birthplace of democracy inevitably associates this architecture with European hegemony and its own narratives of cultural and racial supremacy.11 Thus Villa Maché, along with the luxurious single-family homes in California and Corsica designed by Xenakis that end the book, foregrounds the ongoing commodification of the Mediterranean landscape and stand as painful emblems of the enduring political problems of modernism: a legacy of fabricated narratives; of autocratic and exclusive design approaches; and of disconnected, often frank inhumanity. When it comes to facing these problems, too often the architect is, in fact, absent.

Despite every book being a distinctive opus not the least because the publishers authored several texts in each volume, each carries out kyklàda.press’s vision to complicate the archipelago’s intellectual landscape by reconnecting the islands “with the mainland and each other” through explorative writings on contemporary topics. Perhaps to evaluate these four volumes as a single project—as a collection that grapples with diverse takes on broader questions of gender, public health, urbanization, modernity, and gentrification from a specific and grounded location—is only possible because they were handed to me as such. Perhaps this approach will lose its validity as more volumes authored by other contributors are released, thus dissolving that sense of homogeneity. In the meantime, recognizing the daring decision to contextualize a book series in the Aegean Archipelago doesn’t exempt its authors from the responsibility to articulate a critique of this location’s definition and maintenance within geographies of cultural power, as well as to address unsettling questions about Antiquity and universal knowledge—including whether it is still useful to try to understand the world through that lens at all.

If the publishers decide that it is, then challenging the usual centers of knowledge production is an all-the-more necessary and ambitious task, one that can only be achieved by deconstructing the Mediterranean as a “common horizon” and reconstructing it as the sum total of certain geographies, imaginaries, economies, cultures, and politics aggregated around a body of water.12 By more assertively stirring critical positions at the level of its framing, the growing and already necessary catalogue of kyklàda.press might better support the emergent voices that question established narratives of modernity and European hegemony—a universally needed task, if there ever was one.

-

See Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, vol. 2 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972) and Jean-François Lejeune, Michelangelo Sabatino, Barry Bergdoll, Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean: Vernacular Dialogues and Contested Identities (New York: Routledge, 2010), xv. ↩

-

See Rafi Segal, Cohen Yonatan, Matan Mayer, “Seabound Cities and Mediterranean Ports,” Open Democracy (2011); Antonio Petrov, The Mediterranean (Cambridge: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2013); Neil Brenner, Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization (Berlin: Jovis, 2014). ↩

-

See Marc Angélil, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, and Something Fantastic, Migrant Marseille. Architectures of Social Segregation and Urban Inclusivity (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2020). ↩

-

Paul B. Preciado, Juan Duque, Nicolas Lakiotakis, and Denis Maksimov, The Sleeping Hermaphrodite: Waking Up from a Lethargic Confinement (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020); Dimitra Kondylatou, Nicolas Lakiotakis, Hulya Ertas, Public Health in Crisis: Confined in the Aegean Archipelago (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020); Juan Duque; Lakiotakis, and Dimitra Kondylatou, Free Love, Paid Love: Expressions of Affection in Mykonos (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020); Hulya Ertas, Mâkhi Xenakis, Sharon Kanach, David Bergé, Dimitra Kondylatou, and Sven Sterken, The Architect Is Absent: Approaching the Cycladic Holiday House (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020); David Bergé, Milica Ivić, Antigone Samellas, and Valentina Karga, Architectures of Healing: Cure through Sleep, Touch, and Travel (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2021); Antigone Samellas, Christina Phoebe, Gloria Anzaldua, Liwaa Yazji, George Papam, and Nicolas Lakiotakis, (Forced) Movement: Across the Aegean Archipelago (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2021). ↩

-

In The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, French geographer and historian Fernand Braudel ties pre-industrial capitalism to circulation and credit, with sex work, just like any other form of human commerce, contributing to the consolidation of this budding economy. ↩

-

“Italy’s Matteo Salvini Shuts Ports to Migrant Rescue Ship,” BBC News (2018), link; María Martín Marc Bassets, Lucía Abellán, “France Says It Is Acting to Solve ‘Open Arms’ Migrant Crisis,” El Pais (2019), link. ↩

-

Fernando González Ochoa, El Hermafrodita Dormido (Barcelona: Editorial Juventud, s.a., 1933). ↩

-

Juan Duque, “The Sleeping Hermaphroditus, Roman type,” in The Architect Is Absent: Approaching the Cycladic Holiday House (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020), 68. ↩

-

Xenakis and Le Corbusier parted ways on bad terms after Xenakis publicly disavowed his boss for taking credit for his design of Philips Pavilion for the Brussels World Expo. ↩

-

Sven Sterken, “Iannis Xenakis, Selected Projects from Critical Index,” in The Sleeping Hermaphrodite: Waking up from a Lethargic Confinement (Athens: kyklàda.press, 2020), 68. ↩

-

Penelope Papailias, “Mëmory—Monumeиts,” dëcoloиıze hellάş (2021), link. ↩

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is assistant professor of urban design at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). As an architect, urban designer, and scholar, Malterre-Barthes is interested in the urgencies of contemporary urbanization and how struggling communities can gain greater access to resources, better governance, and ecological/social justice—that is, the strategic practice of urban design. Malterre-Barthes earned her doctoral degree from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich while directing the MAS Urban Design. She is the coauthor of Housing Cairo: The Informal Response (2016), Some Haunted Spaces in Singapore (2018), and Migrant Marseille: Architectures of Social Segregation and Urban Inclusivity (2020). Malterre-Barthes is a founding member of the Parity Group and of the Parity Front, activist networks dedicated to improving equity in architecture.