Architecture is a field replete with and enriched by an ever-growing list of “masters.” However, minority architects are added to this list with conditions. Namely, they become subjects from whom the privilege of individualized narratives is withheld in favor of redundant and reductive stories that record minority success. Among the many figures who have suffered in the shadow of architecture’s simultaneous acknowledgment and disregard stands mid-century architect Norma Merrick Sklarek.

Architecture history recalls Sklarek with an obsessive interest in her background and minimal documentation of her architectural output. A cursory glance at most mainstream sources that boast an in-depth profile will offer a stack of the same key points. They will focus on her humble beginnings in New York; introduce her as the only child of a doctor and a seamstress raised during the Depression; highlight her proficiency at prestigious schools; and emphasize the obstacles she overcame to find work in the field. Some might even mention that she co-founded an all-woman firm,1 pepper in her marriages and children,2 and finish by stating that she died in California on February 6, 2012.3 Typically irrespective of the contents, the headline seems to always include that Sklarek was the first African American woman to receive an architecture license in New York and in California, and that she was the “Rosa Parks of Architecture.”4 Based on the public record, it would appear that a tour of Sklarek’s successes generally ends there.

Professional journals have tended to narrowly focus on Sklarek’s struggle in relation to her gender and race, depicting her story as the Black woman’s journey to the title “architect,” rather than with a more nuanced description of her professional career.5 This narrative persists in the February 1984 issue of Architecture: The AIA Journal, produced by the national nonprofit organization that sets the standards of the profession, which takes great care to record Sklarek’s presentation at a conference about the experience of female architecture students.6 Similarly, the October 1991 issue quotes Sklarek from a group interview and centers not her work or the work of other female practitioners on the panel but their experiences in the field in contrast to those of their male counterparts.7 Widely published architecture journals such as this one emphasize Sklarek’s overcoming gender-based discrimination to achieve success. However, neither the interviewers nor the journal seem to be aware that female architects are further limited and pigeonholed by these repetitive framings.

Rather, this targeted questioning only reinforced how Sklarek, along with other members of minority groups in her field, was identified, both in panel discussions and in the workforce, based on her outlier status. Sklarek was indeed an African American architect of many firsts and unacknowledged successes, yet her prowess as an architect was consistently played down. Sklarek herself wrote in letters that she felt “highly visible” and therefore was pressured to work harder while also being “given challenging assignments and the opportunity to advance.”8 As this pressure supposedly formed Sklarek into a diamond, she became a representative figure not for architects, broadly, but for barrier-hurdling Black women in the industry. Seen in this racialized, gendered light, Sklarek is both heard and silenced in the written history that is her career.

Nuts and Bolts

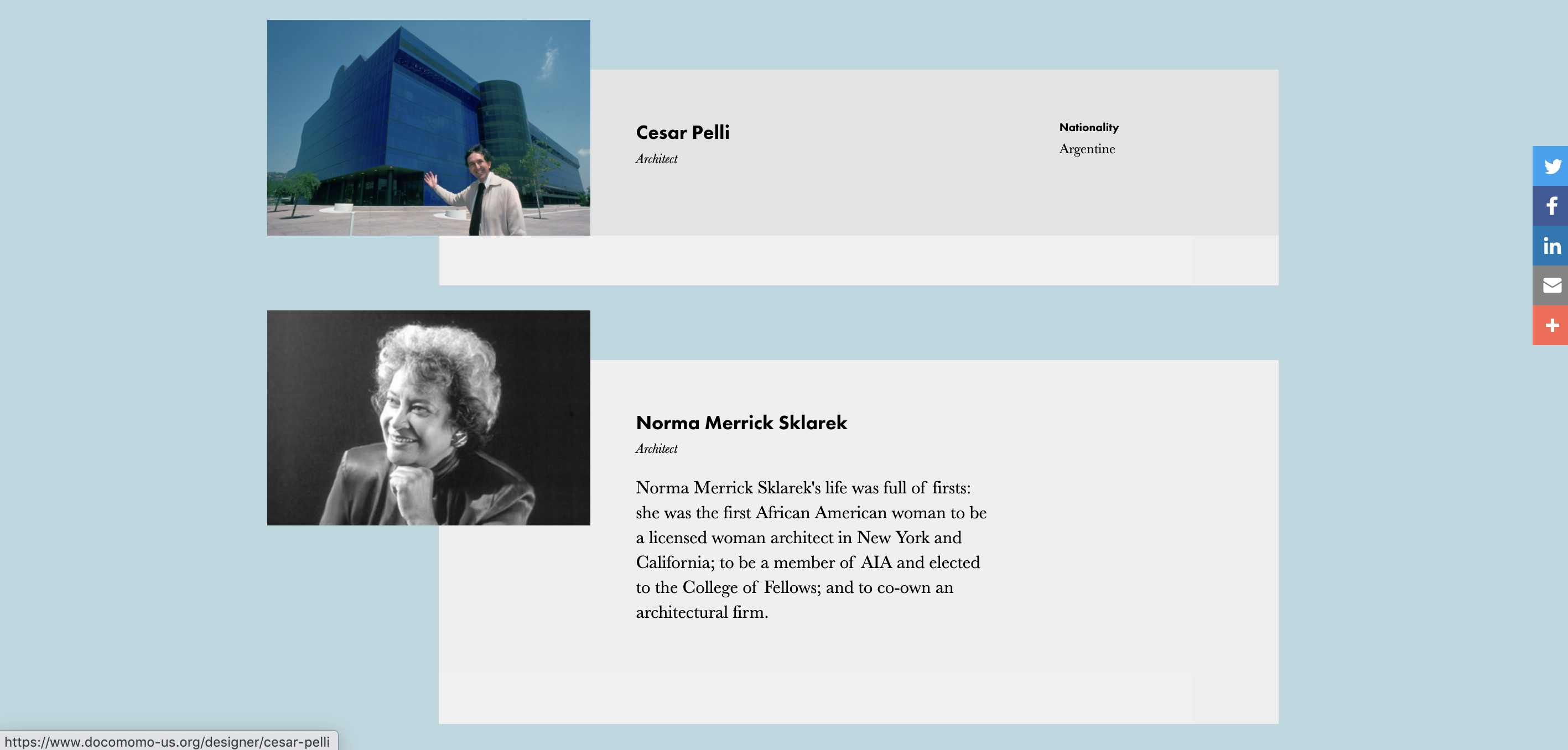

Sklarek’s most acclaimed works are buildings that have typically been attributed to her employers. Having worked in management positions at well-established firms such as Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM), Gruen Associates, and Welton Becket, misattribution of Sklarek’s work as a firm-wide contribution is recurrent across offices. During her time as Gruen Associates’ first female director, Sklarek worked alongside several renowned architects. One of the most notable was the Argentinian architect César Pelli, Gruen’s design partner with whom Sklarek collaborated on the United States Embassy in Tokyo.9 Numerous Western records attribute the embassy’s design solely to Pelli or to Pelli’s collaboration with Gruen Associates.10

In a 1972 article in the “Women in Business” section of California Business, Sklarek recounts her role in the US Embassy design process:

First, the building is designed. Usually it is done by César Pelli, an exceptionally talented architect who is inspiring to work with. Then my department and I come up with the working drawings… detailed instructions to the contractor on how every item is to be built and how all engineering and structural tasks (electricity, air conditioning, plumbing, ceiling spaces, ventilation, etc.) should be coordinated.11

In this brief account of how a building comes to be, Sklarek unveils logics of architecture production that the layperson is usually not privy to. That the interview takes place in a business journal reflects back onto architecture, revealing a culture that considers these tasks not necessarily design but a kind of tedium, purposefully pushed into the background of architecture’s history-making. It is thus no coincidence that a minority architect such as Sklarek would also recede behind the name of a male architect in similar fashion. Narratives about conceptual design by a singular architect do not bring with them all the accompanying labor and myriad details required to specify and execute that design. However, in an article in Martha Stewart magazine, Sklarek’s son, David Merrick Fairweather, shares that his mother in fact preferred the material reality of design. According to Fairweather, Sklarek found design less interesting than bringing it to life: “She would make it real… What kind of concrete. What kind of nuts and bolts. What kind of glass. She was in production, and she would tell you production was the real work.”12

Much like that of the stereotypical housewife, Sklarek’s essential, back-of-house role is ignored, caricatured for the public as distant administration; those crucial tasks, of resolving designs and ensuring that they are code-compliant and able to be fabricated, are easily dismissed. These “nuts and bolts” that Sklarek’s son refers to are required to maintain the efficacy of both an office and a project, yet according to standard historiography, they hardly merit mentioning. If not erased completely, this specialized knowledge is then embodied and referenced as a false depiction of Sklarek’s character. For example, the “Women in Business” article begins by introducing Sklarek to readers: “She might not spit nails, but she can sure tell you where to put them.”13

Far too often, getting to know Sklarek means getting to know a set of accolades and analogies. It typically does not mean learning the theoretical nuts and bolts of her practice. In 1991, Sklarek published an article in Architectural Record about how she perceived an upcoming revival of classical architecture’s complexities in modern building design, enabled by new “drafting and detailing” technologies.14 She makes the argument that “new and old production techniques, often combined, are meeting the demands of complex design technology,” perhaps signaling a rediscovery of approaches to designing office buildings and public buildings of congregation, two typologies that Sklarek specialized in. Yet the potential for these hybrid techniques to increase the capability of reproduction for such clean, manufacturable designs was denied to the architecture community, as these topics took a backseat to dominant and repetitive race- and gender-focused questions. Due to this misplaced attention, the public had less of a chance to understand the type of designer and theorist that was behind the generic image of a “successful African American architect.”

Despite her diminished opportunities to apply this understanding in practice on large projects, Sklarek’s poignant writing still demonstrated deep knowledge of what its possible evolution in design could look like. In a Princeton University discussion panel, the architect Kate Diamond, a former partner and co-founder of Siegel, Sklarek, and Diamond, mentioned that Sklarek missed and craved the large-scale work commonly awarded to large firms. Sklarek eventually left her own firm as it, perhaps owing to the founders’ gender and status, was not commissioned for projects at this scale.15 The limitations that came with working at a top firm that could support Sklarek’s desire to realize large, forward-thinking projects may be the reason she was placed second to those who focus on conceptual design. This aspect of Sklarek’s career is recycled throughout sources as authors extrapolate information about the architect based on one another’s writings to hand-stitch the missing insight on Sklarek’s process. Sklarek’s entry in Powerful Black Women quotes I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America, which captured the idea of Sklarek as an architect modestly designing for the public, with the belief that architecture is “not just in the image of the architect’s ego.”16 It is from this sentiment that we get others, like that Sklarek felt “architecture should be appealing, functional, and most important, pleasing for the persons for whom it is designed.”17 These inferences and interpretations might seem inconsequential, but among the repetitive recounting of Sklarek’s work, they ultimately reproduce narratives that are further and further removed from Sklarek's own characterization of her work.

Two Terrific Builders

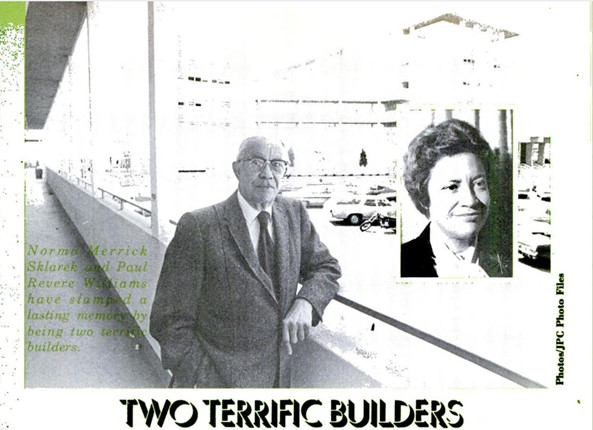

The absence of detailed writing on Sklarek’s architecture and business acumen could be incorrectly dismissed as a lack of recognition for Black architects during her time. One counterexample to this hypothesis can be found in an Ebony Jr article, “Two Terrific Builders,” which (as the title suggests) presents the magazine’s young Black readership with a comparative biography of Sklarek that highlights similarities in her trajectory with the African American architect Paul Revere Williams.

The piece highlights cases in which Sklarek’s career runs in parallel with that of Williams, but nonetheless her contributions remain relatively unmentioned while Williams’s are described in extensive detail. In fact, Sklarek’s work appears only ever in relation to Williams’s, specifically his Los Angeles International Airport (LAX): “Ms. Sklarek’s latest project is right along that new path—she is part of a team working on a new commuter terminal at Los Angeles International Airport… Once again Norma Sklarek is tied to Paul Williams’s work, because that’s the same airport which he had a major hand in building.”18 This statement validates Sklarek’s success by using Williams’s work as a type of milestone and implies that all projects relating to the LAX building were touched by Williams. Though Williams did contribute to designing the Los Angeles International Airport building in 1959 alongside Pereira & Luckman Associates and Welton Becket & Associates, this involvement predates by two decades Sklarek’s 1984 Terminal One Project.19

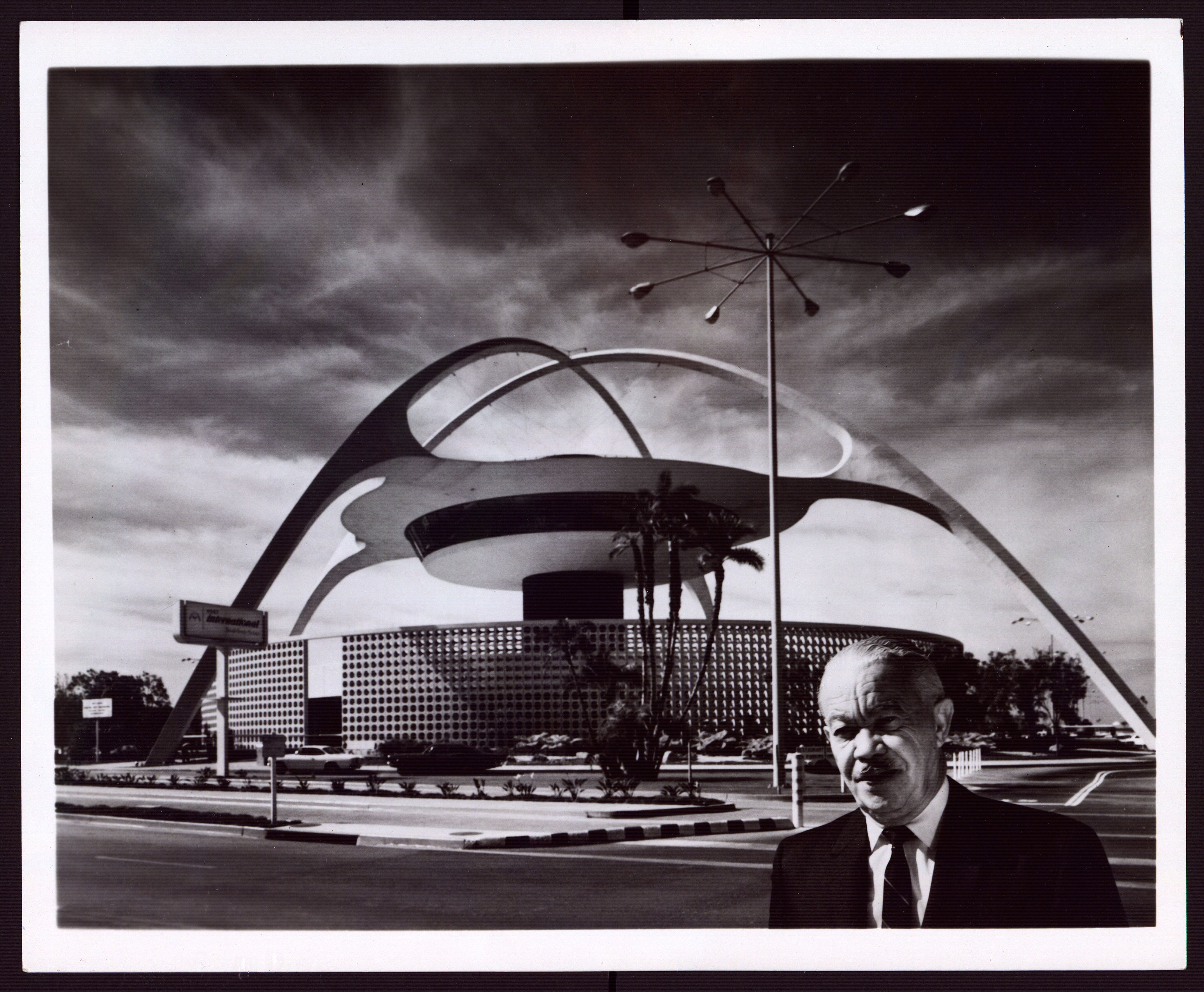

The key reason for this miscommunication is supposedly the iconic 1961 image of Williams in front of LAX’s Theme Building, which circulated widely after the project’s construction. A 2005 New Yorker essay, “Hotel California,” explains that this single image may have led to the popularly held belief that Williams designed the pavilion. The piece states:

But the totem of modernism with which Williams is most often associated is one he had little to do with: the soaring, aerodynamic double parabola of the theme pavilion at Los Angeles International Airport. Despite many articles and books crediting him, Williams was not on the design team for the theme pavilion. (He was a member of the joint-venture office for the entire airport project.) The story, which has annoyed the architects who did work on the drawings—many of them were from William Pereira and Charles Luckman’s firm—originated with a photograph taken by Julius Shulman in 1965, a few years after the dedication. It shows Williams, his hair white and the wrinkles in his forehead deep, standing before the building with a quizzical expression on his face.20

In an episode of KCET’s public history video series “Lost LA,” the architecture historian Rebecca Choi details Williams’s contributions to the LAX project: Williams signed off on Pereira & Luckman Associates’ design concepts by executing construction drawings and taking care of material specifications.21 This work was not unlike Sklarek’s contributions to Gruen Associates’ projects, and a comparison between Williams and Sklarek could have been made simply by saying that they both played a major role in the airport’s practical execution. However, considering Williams’s incorrect accreditation, the narrative of Lewis’s article becomes one of exaggerated success and participation for the architects she is covering. This unreconciled misconception in Ebony Jr implied to its impressionable audience that Sklarek and Williams were both at the forefront of these projects when they in fact played the crucial but hidden role of project manager. African American architects did indeed work alongside others to help create indispensable civic projects such as the terminal, but they were not the lead designers nor the intended faces for them. This is a distinction that should not be lost.

This mistake magnifies an institutionalized aversion to clarity in architectural history. Reductive narratives and miscommunications circulate throughout Sklarek’s and Williams’s histories, and there has been little apparent urgency to resolve them. Left unaddressed, these unmediated mistakes damage the integrity of the minority architects’ legacies. The public could easily misconstrue Sklarek and Williams as taking undue credit for the popular work of nonminorities to make a name for themselves. Architecture history-making would rather settle and allow the public to celebrate at face value that African American men and women are included than admit that neither Williams nor Sklarek were in the glorified positions for which they are sometimes credited.

“Rosa Parks of Architecture”

Minority architects are misrepresented and restricted most clearly when connected to non-white icons outside the field. Recognition of diversity can erase individuality. Every white male architect is seen to design independently, regardless of his professional attachments, while non-white architects are not afforded this benefit. Without regard to what it implies, architecture has continually heralded Sklarek as the “Rosa Parks of Architecture.”22 It is the title that the field proudly brandishes under her portrait. This umbrella effect of inclusion could be just as harmful to the diversity it ostensibly aims to celebrate. Erasure takes many forms; a person’s own story may be left un-investigated because, to the writer, it appeared too similar to a previous story to be worth distinction. It was, in other words, (over)written before it was written.

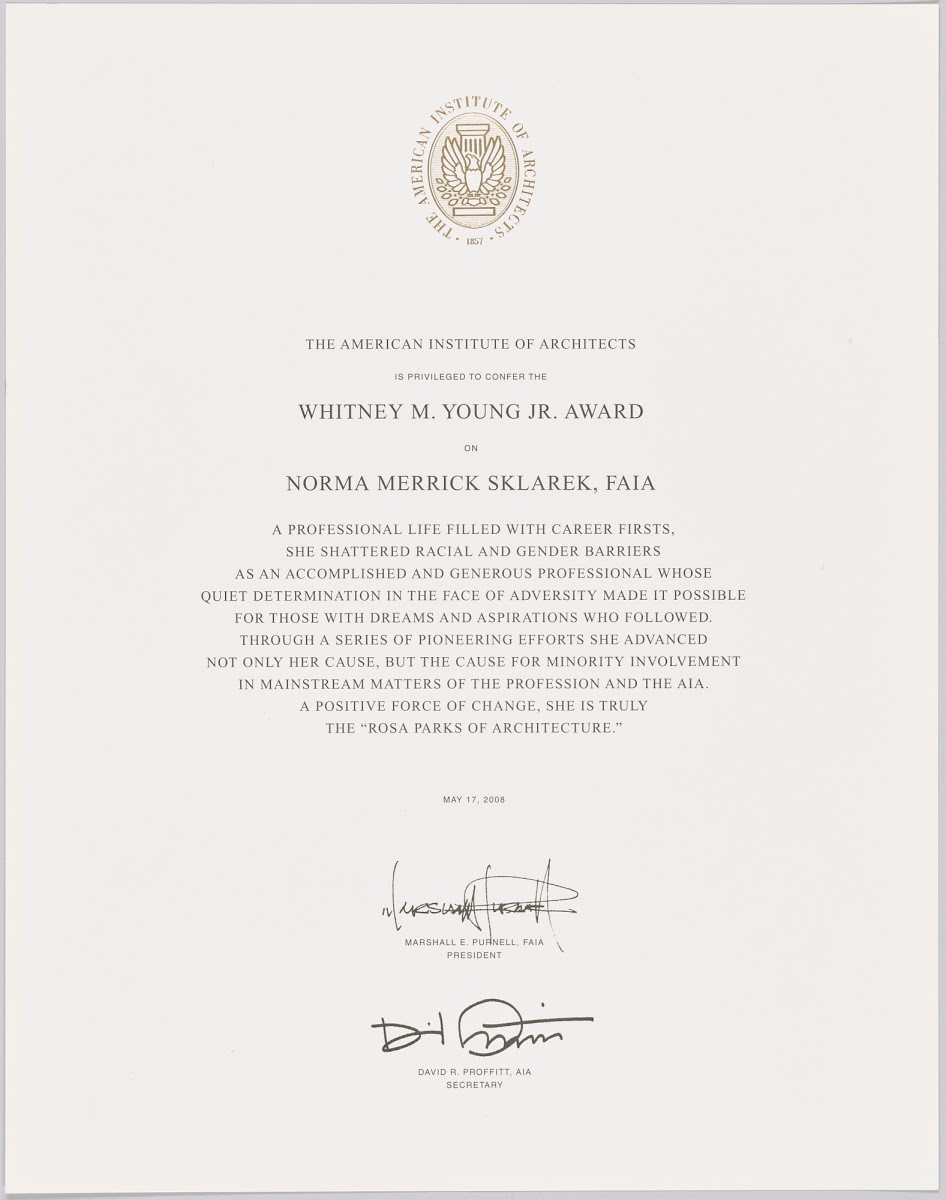

Sklarek should never have been called “the Rosa Parks of Architecture,” a nickname she received in writing when she was awarded the AIA Whitney M. Young Jr. Award in 2008.23 Setting aside the sole parallel that they both demanded that society shift toward unbiased equality, Sklarek and Parks both being Black women is not synonymous with their being of the same ideology, lifestyle choices, or legacy. The emphasis on gender and race minimized both Sklarek and Parks as individuals, collecting them and their separate lives within a generic grouping of Black women. Not only does this unnecessary parallel imply that no amount of success will break them from this category, it overshadows any sense of Sklarek’s individual accomplishments, reducing her architecture career to a mere instance of a Black woman who was considered successful after battling societal odds. This comparison, made originally in 2008 by the AIA board and reproduced by Marshall Purnell and David Proffitt, who signed the award certificate, is an example of an unfortunate trend in both architecture and public historiography: erasure by impassive comparison.24

Though a “subway student,” Sklarek did not refuse to leave her seat.25 She created seats, for herself and the generations after her, in rooms where she was not readily considered a potential occupant. And she created those seats by being good at her job. The focus on her race distracts from Sklarek’s proficiencies as an architect, and in the public eye it diminished any professional esteem she had earned, replacing it with each popular wave of Black women empowerment. In receiving this nickname, the normalized burden of enduring architecture’s institutionalized neglect was yet again forced upon Sklarek. Meanwhile, institutions profit from this publicly generated version of Norma Sklarek.

In October 2020, Columbia University introduced its Norma Merrick Sklarek ’50 B.Arch Scholars Fund. The $1 million fund was created by Sklarek’s alma mater under a banner to “promote diversity, inclusion, and equity by breaking down barriers to access for graduate study.”26 Other colleges, like Howard University, soon followed with similar funds, such as the Norma Merrick Sklarek Architectural Scholarship Award.27 Scholarships such as these use Sklarek’s name and trajectory to invite more students into the very institutions that had done nothing at the time to negate the exclusion and demographic discrimination of the field in which Sklarek found success. According to Roberta Washington, a fellow Black female architect who attended Columbia, the university had previously capitalized on moments when providing financial support to minorities benefited the school’s image.28 In other words, this approach to increasing the acceptance rate of minority students often serves as an act of propaganda to ensure a school’s reputation is seen as inclusive, rather than an indication of true intentions to change disadvantageous circumstances. The field of architecture tends to choose, consciously or not, to see its diverse members as outliers—albeit often “outstanding ones”—in their communities, rather than designers who are more in need of genuine championing from their peers than false titles.29

This recall to an earlier era of championing civil rights is represented not only in word and fundraising but also in photography. Sklarek died in 2012 and practiced at a time when color photography was common. So why are the most common portraits of her rendered in black and white, especially while her buildings are rendered in color? Plenty of color images of Sklarek can be found in filmed interviews,30 websites,31 and even her memorial video.32 Whether this is a subliminal tactic to imply a distant past when overcoming racial adversity was quite a feat or is meant to literally soften her Blackness into hues of gray, its repeated use at the exclusion of other options is offensive.

New Archives, Future Legacies

In 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement began with a hashtag in a tweet.33 What three Black women started in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin, as a way to “intervene in the violence inflicted on Black communities,” evolved into a broader cultural reckoning with the ongoing victims of White supremacy and the institutional erasure and marginalization of this harm.34 This has led to a renewed interest at all sorts of institutions in the lost or disregarded Black people of various professions, skill sets, and achievements.

The recently initiated Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection is perhaps one such instance.35 Held at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), the archive’s materials have in part been digitized and made publicly accessible online. Despite a clear intention to bring Sklarek’s less documented perspective in the architecture field to the foreground, it is disheartening to note that this archive makes evident that public media facilitated a two-pronged dissemination of misinformation and praise that has dulled any real insight into her role as an architect and a role model for future designers. Take, for instance, Nancy Anita Williams’s article in the Washington Post on a Howard University conference for female architects, which incorrectly states that “no black female architects were licensed in the United States until 1954 when Norma Merrick Sklarek, the conference’s keynote speaker received her certification in New York.”36 This is a common claim. The first African American woman to be licensed in America was Chicago-born Beverly Loraine Greene in 1942.37 Another archived article from the June 1984 issue of Ebony reiterates this falsity. While Sklarek was first to be licensed in New York and California, she was not first in the whole of the United States.38 Both articles used the rhetoric of “first” as a means of empowerment, unknowingly regurgitating the language that literature from outside the African American community uses to depict Sklarek as a prize rather than a professional.

Alongside the traditional archival collection, Sklarek’s story is also recalled by other means. One of the first multimedia events centering Sklarek appeared in March 2019, when Princeton University hosted Norma Merrick Sklarek: Redefining Public, organized by graduate students from Women in Design and Architecture and the School of Architecture. This two-day conference focused on the curation of and investigations into Sklarek’s personal and professional life. Most of the event was recorded, including in-person panels and moderated discussions with Sklarek’s colleagues and collaborators. Firsthand accounts and oral testimonies recovered versions of Sklarek that existed outside architecture’s oppressive frame. Former partner Kate Diamond provided an incredibly valuable internal view of Sklarek’s personality and collaborative process, while Hazel Ruth Edwards, Howard University’s Chair of Architecture, discussed what it was like to attend one of Sklarek’s conferences at Howard in 1983. This non-printed method of public remembrance offers an opportunity to excavate an architect as fleshed out and visceral, contrary to the more narrowly written representation of figureheads.

NMAAHC curator Michelle Joan Wilkinson stated during the Princeton conference: “One’s legacy is bound up in part on the evidence of photographs and documents that visually and legibly attest to one’s contribution. Images become part of legacy making, aid in our consumption of a particular narrative of a person, place, time, and event.”39 As legacy-makers, historians use archives as tools of reconstruction. But when our archives are filled with the same incomplete images, so too are the legacies they construct. The palatable narrative of Sklarek is that she overcame the limitations and barriers of gender and race. It rarely, if ever, addresses that her more privileged peers generally did nothing to ease or support her struggles toward success.

In an obituary for Sklarek, Marshall Purnell, a former president of the AIA, states that Sklarek did not design many of the larger-scale projects she supervised “not because she wasn’t capable” but because

it was unheard of to have an African American female who was registered as an architect. You didn’t trot that person out in front of your clients and say “This is the person designing your project.” She was not allowed to express herself as a designer. But she was capable of doing anything. She was the complete architect.40

This is the truest quote I have found of Sklarek’s era. Her professional community stopped at commending her for overcoming adversity; they did very little to change the conventions and challenge the biases of their members and clients. This complicity has yet to be comprehensively, articulately addressed in the archives on Sklarek, Williams, or any other minority architect.

It is critical that historians are recognized as “makers” of history, with the responsibility to look beyond and push against archives’ limits as they build the discursive foundations for the classroom lessons, magazine articles, and buildings of the future. The deficiencies of Sklarek’s archive to date should encourage the public to ask why the complexity of recorded history is so often traded away in favor of the cleanest narrative and best-selling story. We are presently in an era in which minority figures are often publicly, actively recovered with an intent to avoid the standardized pitfalls that have, until now, shaped their image. This is therefore a prime time for an autopsy of capital-A Architecture’s narratives, and for a reevaluation of what is considered truth. The architecture community must acknowledge the silhouette of that which has been discarded, and encourage discourse on how to prevent such active erasure in the future.

-

Brian Lanker, I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America (New York: Stewart, 1989), 40. ↩

-

Elaine Woo, “Pioneering African American Architect,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2012, link. ↩

-

Susan Griffith, “Norma Merrick Sklarek (1928–2012),” BlackPast, March 9, 2012, link. ↩

-

Patricia Morton, “Norma Merrick Sklarek,” in Pioneering Women of American Architecture, ed. Mary McLeod and Victoria Rosner (Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, 2022), link; Woo, “Pioneering African American Architect”; Jackie Craven, “Biography of Architect Norma Sklarek,” ThoughtCo, July 3, 2019, link; Megan Cahn, “Meet Norma Merrick Sklarek: The First Licensed African-American Female Architect,” Martha Stewart, March 12, 2018, link. ↩

-

Renee Kemp-Rotan, “Being a Black, Female Architect in a White, Male Profession,” Architecture: The AIA Journal (February 1984): 11–14, link. ↩

-

Kemp-Rotan, “Being a Black, Female Architect,” 11–14, link. ↩

-

Nancy B. Solomon, “Women in Corporate Firms: The Top Positions in Large Offices Aren’t Just for Men Anymore,” Architecture: The AIA Journal (October 1991): 79–87, link. ↩

-

Norma Sklarek, “Letter to Carolyn Armenta Davis,” May 4, 1993, NMAAHC.A2018.23.6.1.12.011, box 1, folder 12, Professional Correspondence 1964–1993, Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

Craven, “Biography of Architect Norma Sklarek.” ↩

-

See, for example, César Pelli, “Skin & Bones,” 1980, recorded lecture, link; César Pelli, “US Embassy, Tokyo,” CultureNOW: A Celebration of Culture & Community, July 13, 2020, season 1, episode 53, streaming audio, link. ↩

-

Carol O’Maley. “Women in Business: Threat of Lawsuits Can Hinder Architects, Designer Contends,” California Business, September 25, 1972, Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, 1944–2008, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

Cahn, “Meet Norma Merrick Sklarek: The First Licensed African-American Female Architect.” ↩

-

O’Maley, “Women in Business.” ↩

-

Norma Merrick Sklarek, “Contemporary Details,” Architectural Record (February 1991): 44. ↩

-

“Norma Merrick Sklarek: Redefining Public. 1PM - Collaboration Panel,” Princeton University School of Architecture, March 28−29, 2019, link, March 29, 2019, time stamp: 20:10. ↩

-

Lanker, I Dream a World, 40. As quoted in Jessie Carney Smith, ed, Powerful Black Women (Detroit: Visible Ink Press, 1996), 309. ↩

-

Smith, Powerful Black Women, 309. ↩

-

Mary C. Lewis, “Two Terrific Builders: Norma Merrick Sklarek and Paul Revere Williams,” Ebony Jr, March 1983, 9–11. ↩

-

“Los Angeles International Airport—Los Angeles—Paul Revere Williams,” Paul R. Williams Project, link; Max Bond, “Still Here,” Harvard Design Magazine, President and Fellows of Harvard College, link. ↩

-

Dana Goodyear, “Hotel California,” New Yorker, January 31, 2005, link. ↩

-

Rebecca Choi, “Paul Revere Williams: An African-American Architect in Jet-Age LA,” season 4, episode 4, KCET Lost LA, link. ↩

-

Cahn, “Meet Norma Merrick Sklarek”; “Norma Sklarek,” Columbia Celebrates Black History and Culture, Columbia University, link; and Morton, “Norma Merrick Sklarek,” among many others. ↩

-

“Whitney M. Young Jr. Award,” Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, 1944–2008, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

Jack Travis, African American Architects in Current Practice (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991), 66; and “Palisadian Architect Norma Sklarek Broke Color and Gender Barriers,” Palisadian-Post, March 14, 2012, link. ↩

-

“Norma Merrick Sklarek Scholars Fund,” Columbia GSAPP, January 15, 2021, link. ↩

-

“The Distinguished Career of Norma Sklarek: One of the First African-American Female Architects,” NCARB, July 16, 2018, link. ↩

-

“Columbia GSAPP Event Series: Beverly Loraine Greene and Norma Merrick Sklarek,” time stamp: 1:32, Columbia GSAPP, January 15, 2021, link. ↩

-

Jason Spencer, “Norma Merrick Sklarek.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. May 6, 2021, link. ↩

-

“Norma Sklarek – African American History Month 2016 #Blackhistorymonth,” Adafruit Industries, February 15, 2016, link. ↩

-

Norma Merrick Sklarek Memorial Slideshow, YouTube, 2016, link. ↩

-

“A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: The Black Lives Matter Movement,” Howard University School of Law Library, link. ↩

-

Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, 1944−2008, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. ↩

-

Nancy Anita Williams, “Howard Conference a Rallying for Black Female Architects,” December 15, 1983, NMAAHC-A2018_23_7_2_1_15_001, box 1, folder 15, Published Materials 1965–2004, Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

Roberta Washington, “Beverly Lorraine Greene,” in McLeod and Rosner, Pioneering Women of American Architecture. ↩

-

“Black Women Architects, a Blueprint for Success,” Ebony, June 1984, 56–60, Norma Merrick Sklarek Archival Collection, 1944−2008, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, link. ↩

-

“Norma Merrick Sklarek: Redefining Public. 6PM - Keynote Presentation.” March 28, 2019, time stamp: 16:36. Princeton University. The Trustees of Princeton University, 2021, link. ↩

-

Woo, “Norma Merrick Sklarek Dies.” ↩

Gealese Peebles is a designer based in Columbus, Ohio, with a Liberal Arts Bachelor’s degree in Architectural Studies from Kent State University and a passion for discourse. The representation of minorities and interdisciplinary collaboration are her primary focus when contributing to conversations on the future of the architecture field and the built landscape.