At the entrance of Sick Architecture at CIVA Brussels, co-curated by Beatriz Colomina, Silvia Francheschini, and Nikolaus Hirsch and completed in conjunction with students in the Princeton Architecture PhD program, is Hans Hollein’s “pills for architecture,” a collection of (hypothetical) pharmaceuticals meant to structure architecture from inside the body by changing the body’s physical state and thus its relation to surrounding space. Created by the artist in 1967, these “non-physical environments” or “environmental control kits,” as they’re described in the accompanying wall text, were imagined as useful to those suffering from maladies like claustrophobia and agoraphobia. In addition to supporting Hollein’s manifesto that “everything is architecture” (from the artwork text: “Mankind creates artificial conditions. This is architecture. Physically and mentally repeated, transformed, he expands his physical and mental area, determines his ‘environment’ in the broadest possible sense”), it also reveals the neoliberal machinations already at work in the late 1960s by displacing the responsibility within the person−architecture relation onto the human. If one finds oneself at odds with the architecture around them, the answer is not to change that space but to change oneself; and if everything can be architecture, then the responsibility of every relation falls upon the individual.

In the context of a global pandemic that has taught us that health cannot exist without community, even despite neoliberal pressures on the individual to be the sole arbiter of community healthcare decisions, these “pills for architecture” seem especially prescient. After all, what is a mask but one’s own personal architecture, or “control kit,” turning the collective experience of being bodies in space, of breathing the same recycled air, into an individual one? And even more important, what is a world where a “suggestion” to wear a mask stands in for more effective governmental financial and health assistance and corporate responsibility but a neoliberal hell?

Sick Architecture is distractingly individualistic. In the show's editorial, the curators write that “every new disease is hosted within the architecture formed by previous diseases in a kind of archeological nesting of disease.”1 However, I'd venture to suggest that the disease shaping the architecture of the show itself is the sickness of the individual that Hollein's pills represent. In layout, its collection of research presentations looks more akin to a trade show or fair than a cohesive exhibition; though some artworks in the show are more typical installations, such as a video work by Mohamed Bourouissa and a hanging work by Vivian Caccuri, most of the exhibition consists of transparent temporary panels and dividers. In fact, not unlike the kind of emergency structures or individual temporary care rooms that proliferated during the pandemic, the scenography is medical. Text and accompanying images are affixed to each panel; however, the images often lack captions, leaving the visitor to wonder what exactly it is they’re looking at. Visitors walk through the rows created by the panels, inundated by the labyrinthine construction and the abundance of texts and images; even looking at an individual panel does not afford one respite from this overwhelming array, as the backs of the images and texts on the other side of the panel are visible.

Engaging these structures engenders a claustrophobic feeling, made worse by a sense of confusion between research presentations and artworks, which do not seem to be conceptually differentiated by the curators. This is, to an extent, understandable—almost every “work” in the exhibition is a presentation of an individual’s research on a topic related to the theme of “sick architecture” (with both “sick” and “architecture” defined in Hollein-style capaciousness)—but the choice of visual layout defies the visitor’s chance to find connections between projects. This feeling is exacerbated by the fact that the physical exhibition only comprises one-half of the show; the other half is a collection of essays published on e-flux meant to accompany the research “works.” The essays are, as a whole, excellent, and the exhibition thus not only calls into question what architecture is and is not but it also raises questions about what an exhibition is and is not. While these questions are present to a certain extent in every exhibition—is the exhibition comprised of the works alone? the wall texts? the files and files of preparatory research and planning that go into the finished project?—they are exacerbated by such a vast collection of materials absent from the physical exhibition space. Even more puzzling, given that they make up such a substantial percentage of the exhibition’s whole, the essays are barely represented in the physical show, though they are mentioned in the introductory wall text, which alludes to an accompanying compendium available on e-flux. I was surprised not to find QR codes for each text on the corresponding panel for each essay, or at the very least quoted passages from the essays in addition to the more general explanatory wall texts (it is unclear whether these shorter texts were written by each contributor or summarized by the curators) and visual materials.

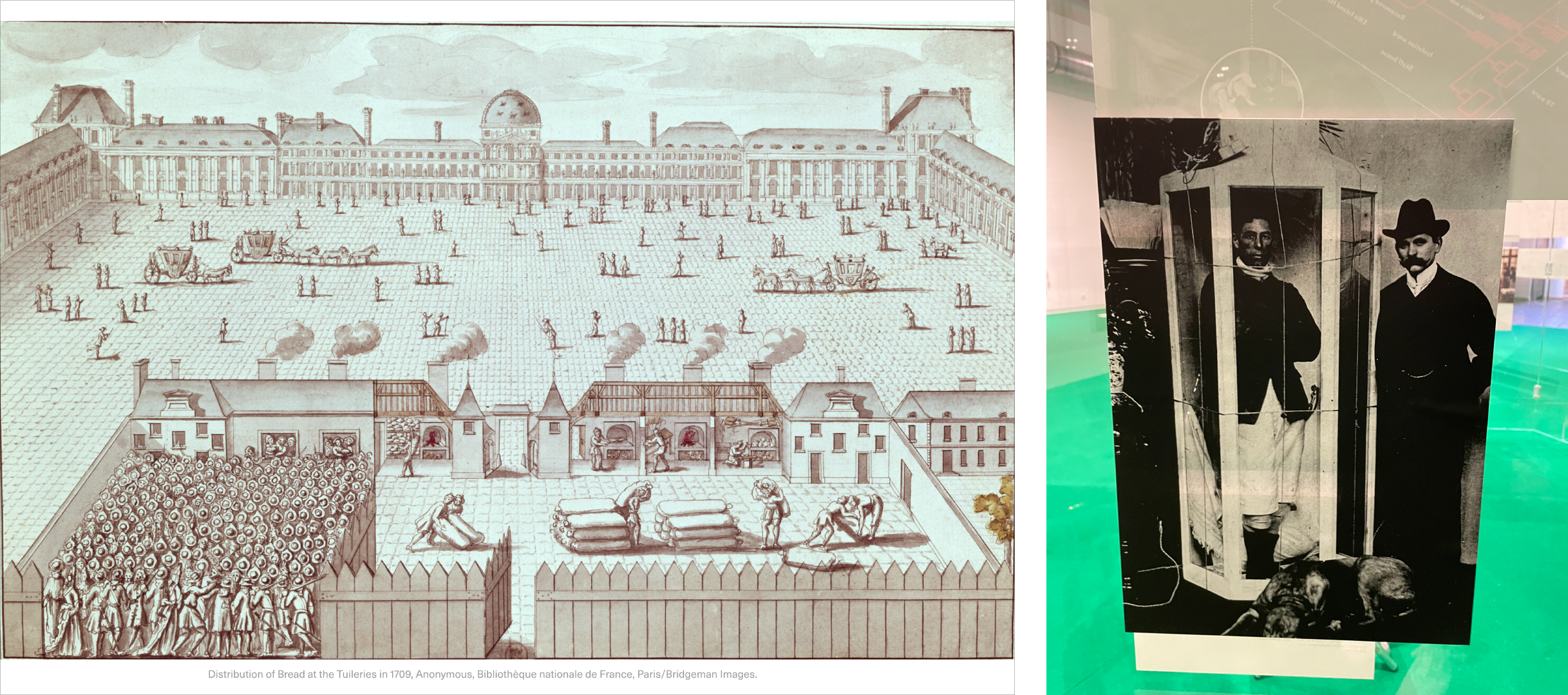

Some essays—for example, Iason Stathatos’s “Hunger Architecture”—were not accompanied by appropriately matching visuals. Stathatos’s exceptional essay, one of the strongest, in my opinion, traces how new architectural apparatuses developed alongside hunger, particularly “the fear of hunger” in eighteenth-century Paris.2 Through its discussion of the granary typology—which emerged to store and preserve grain in the midst of an acute famine—the essay rings especially prescient in the context of COVID, which many people experienced as a pandemic not only of disease but also of food scarcity. The essay evidences how architectural systems have historically been mobilized against hunger and, reading it in 2022, it offers a way to see new collective lines of “defense.” The popping up of free neighborhood food fridges and pantries is, for example, one contemporary manifestation of how communities came together through mutual aid architecture to feed people over the past few years. Ultimately, Stathatos’s essay is about how architecture feeds us. “The hungry Parisians needed non-narcotic bread, but they were also fed with architecture,” Stathatos writes, evoking but also surpassing Hollein’s psycho-pharmalogical project. The essay touches only briefly on hunger artists, performers who starved themselves for weeks at a time for paying audiences in the eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, made most lastingly famous through Franz Kafka’s short story “A Hunger Artist,” but his visual presentation focuses mostly on these curious figures. These visuals ultimately favor spectacle over connection to the essay and indeed to the viewer; and, perhaps more disturbingly, favor individual starvation over collective scarcity, aesthetics over systemic conditions, not eating over not having food, the hunger artist over hunger architecture.

What is meant, then, to be the takeaway from such an assemblage? Are visitors to the exhibition who don’t read the accompanying essays—a daunting task with 35 long-form texts—missing the main point? Any writer will tell you that, while useful, images and summaries can only go so far in conveying the nuances of one’s complete text. While an interesting foray into the making and displaying of a research archive, there is a richness missing that one comes to expect from a visual exhibition, both visually and intellectually—the balance sought between text and image, between online and IRL, is unfortunately not a successful one in the actual space. The presence of these essays seems to recall Hollein’s pills—the viewer is expected to have “taken” in all the information, all the histories they entail, in order to transform their experience of the physical space. Further, while the responsibility of education generally falls on curators and gallery staff, here it falls on the individual visitor. I’m reminded of my undergraduate liberal arts degree: you can do the reading or you cannot, but the available instruction can only take you so far without it. If the goal of the exhibition is to illustrate how architecture has been reframed in the context of numerous health-related moments, most recently COVID-19, isn’t it then also to have the viewer reframe themselves in relation to said architecture? Again, the onus falls on the individual—to read the essays, to make sense of the confusion, to find their own polemic.

By following Hollein’s statement that “everything is architecture,” the exhibition missed a chance to be more polemical on the relation between sickness, health, biopolitics, and architecture. The curatorial strategy to lump as much in as possible—understandable given how many different research projects had to be accommodated—was nevertheless unsuccessful in its fulfillment of the exhibition’s title: Sick Architecture. While the exhibition does tell the viewer—many times—that “architecture and sickness are tightly intertwined” (to quote the press release), it fails to demonstrate it—or, at least, to demonstrate how architecture not only is but should be. Despite the inclusion of projects like Maggie’s Centres, which offer a look into how architecture can aid medicine and offset the intertwining of sickness and architecture through uplifting design, open-air spaces, and a focus on community areas, the exhibition overall fails to push architecture and its responsibility of care forward in its totality, even if some of the individual works—and especially the essays—do. Ultimately, to echo a cliché, it is a whole whose sum is not greater than its parts. The show fails to reach the viewer in an embodied, experiential way, leaving them with the question of what exactly the show offers that the compendium of essays does not—and does not offer better.

The standouts among the works were thus the ones that were actually artworks or focused on individual architectural projects or spatial elements in relation to health, particularly those that show and not only tell what architecture is and how it could be. Goldin+Senneby’s Insurgency of Life (Lego Pedometer Cheating Machines) (2019–) is one such work. Comprised of a collection of Lego robot cars controlled by attached phones, the work is meant to trick smartphone apps used by insurance companies to track patient activity. Understanding that pedometers don’t enable access for everyone, the artist duo hacks the system, using the thrusting of the attached phones to create an enclosed loop—phone moves robot, phone tracks robot movement.

Another such standout is Vivian Caccuri’s Mosquito Shrine II (2020). Caccuri embroidered onto mosquito netting the story of the invasion of the New World through the lens of the mosquito, including such spaces as sugar plantations and artificial dams that contribute to the spread of these deadly insects. The mosquitoes are imaged as a paramilitary force that wages its own war, attacking both colonizers and Indigenous locals in equal measure, revealing that as colonizers worsen conditions, they inevitably worsen them for themselves as well. The contemporary answer to mosquito-borne illness—the mosquito net—tells a story both in the images embroidered on it and in its existence itself. An itinerant architecture, the mosquito net controls and structures space, movement, and health (a nearby research presentation offers images of different mosquito-net structures, while the accompanying essay, “Sanitary Imperialism” by Dante Furioso, tells the history of the connection between these structures and US imperialism).3 The inclusion of fantastical creatures, such as those on the Carta Marina, also reinforces that this work is a map—the action is depicted not only temporally but spatially.

Final standouts are Marie de Testa’s contribution, titled “Hysteria as Scenography,” and Alexandra Sastrawati’s contribution, “Depressed Worlds.”4 Covering Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, a sanatorium that treated women exclusively until 1968, de Testa discusses the way Salpêtrière was structured to both shelter the public from the “mad” women inside and provide a stage for those women to perform their hysteria, through yearly “Mad Woman Balls” and weekly demonstrations on the treatment of hysteria. De Testa captures the eroticism at the heart of these displays and achieves the balance between visuals and essay better than most of her fellow contributors, having chosen a topic with a rich visual archive. Whereas for many of the contributors, I felt that the strength of their essays outweighed that of the presented “works,” I did not have that feeling here. The visuals seem to properly supplement the written material, rather than only tangentially illustrate it—perhaps because de Testa chose a topic so closely informed by performance, where visuality is already at heart. Similarly, Sastrawati displays a rich combination of images and text in her elucidation on the life of artists living with mental illness in Singapore. In her writing, she expertly describes depression as an act of worlding, an additive rather than only subtractive disorder. The city, built for productivity, does not handle depression well. But how does depression produce? Such considerations take us out of the physical relation between architecture and sickness, into the consideration of architecture as mental space.

The biggest disappointment, however, was the inclusion of Elizabeth Diller’s video Exhaustion (2021), which features bodycam footage of George Floyd’s murder interspersed with video of a non-Black person blowing up a plastic bag to measure lung capacity. The video lasts 9 minutes and 29 seconds, the same length as the chokehold that killed Floyd. As the video goes on, the sounds of the bag being blown up are overlaid with the sounds of someone gasping for air. Paired with the overlaying of Floyd’s last words on the full bag, the video stands as a testament to who gets to breathe in the United States. But what is the point of this video, heartbreakingly rendered in full gore and violence to be consumed by an audience? It’s been said over5 and over6 and over7 again that showing these videos contributes to Black trauma; Black writers and activists have asked time and again that we stop sharing them as a result. In the New York Times, Melanye Price compares these videos—and the murders they record—to lynchings when she writes, “Black death has long been treated as a spectacle. White crowds saw lynchings as cause for celebration and would set up picnic lunches and take body parts with them as souvenirs. Their children would pose for pictures in front of swinging corpses, and those photos often became postcards.”8 For PBS NewsHour, Monnica Williams writes that “the trauma of exposure to these videos sits on top of layers of trauma that go all the way back to slavery. It is all one and the same. It starts with the kidnapping of my ancestors from Africa and ‘slave patrols’—bands of white men hired to police communities for slaves who tried to escape, and a forerunner to modern American law enforcement.”9 In the face of such asks and evidence of trauma, why would the curators choose to include this video, particularly in an exhibition about how space impacts health? In the editorial for the show, the curators define “sick” as “not just recognizable diseases but things not yet recognized or treated as disease.”10 Unfortunately, it does not seem that, for them, trauma has made the cut, nor have they recognized the exhibition itself as an architecture that hosts or reproduces this violence.

While Diller’s video does connect Floyd’s heartbreaking “I can’t breathe” to the disparate effects of the respiratory disease COVID-19 on the Black community—a relationship that is undoubtedly spatial, as it is impacted by access to affordable healthcare and food; the transportation of lower-income and racialized workers to jobs they weren’t able to do from home; and diseases like asthma that are worsened by pollution, where exposure results from the siting of bus depots, warehouses, and other locally unwanted land uses (LULUs)11—its benefits do not outweigh its harms. Price continues, on the harm of sharing these modern-day lynching videos, “Instead of transforming policing, the ubiquity of these images may be reinforcing pernicious narratives that black lives do not matter, while affirming the actions of people like Amy Cooper and law enforcement officers like Derek Chauvin who killed George Floyd.” Further, the only way for the video’s inclusion to be well-intentioned is if it was meant to raise awareness and implicate the viewer in Floyd’s murder via the use of bodycam footage, which literally shows the point of view of the police officers who murdered him—it places the viewer inside the killing body, forcing a reckoning and a relation. However, if implication, rather than re-traumatization, was the intent, it means that a certain audience was assumed—specifically, a non-Black audience. The result is an architecture that impacts the health of people disparately, contributing to the trauma of those who would be considered interlopers in the imagined scenography of the exhibition. Given that race is such an important part of the nexus of sickness and architecture, it seems that the curators have not allowed the possible lessons of their show to penetrate their curation.

The presence of an iron lung in the room alongside the video presents an odd dichotomy between assisted and restricted breathing. Like the iron lung, which creates an augmented system of breathing of which the natural lung is only a part, Black breath does not stand alone but rather is impacted by a system of disparate healthcare, the effects of pollution, police brutality, and other traumas.12 This system is undoubtedly a sick architecture; unfortunately, Sick Architecture implicates itself in that architecture. Recalling Hollein’s pills, the responsibility for alleviation of that sickness falls upon the individual visitor, having been abdicated by the curators upon their decision to include Diller’s work.

-

Beatriz Colomina, Iván López Munuera, Nick Axel, and, Nikolaus Hirsch, “Editorial,” e-flux Architecture, November 2020, link. ↩

-

Iason Stathatos, “Hunger Architecture,” e-flux Architecture, May 2022, link. ↩

-

Dante Furioso, “Sanitary Imperialism,” e-flux Architecture, May 2022, link. ↩

-

Marie de Testa, “Hysteria as Scenography,” e-flux Architecture, May 2022, link; and Alexandra Sastrawati, “Depressed Worlds,” e-flux Architecture, May 2022, link. ↩

-

Melanye Price, “Please Stop Showing the Video of George Floyd’s Death,” New York Times, June 3, 2020, link. ↩

-

Monnica Williams, “White People Don’t Understand the Trauma of Viral Police-Killing Videos,” PBS NewsHour, October 6, 2016, link. ↩

-

Allissa V. Richardson, “We Have Enough Proof,” Vox, April 21, 2021, link. ↩

-

Price, “Please Stop Showing the Video of George Floyd’s Death.” ↩

-

Williams, “White People Don’t Understand the Trauma of Viral Police-Killing Videos.” ↩

-

Colomina et al., “Editorial.” ↩

-

For a more effective reading of the spatial relationship between respiratory diseases, Blackness, and police brutality, see Lindsey Dillon and Julie Sze, “Police Power and Particulate Matters: Environmental Justice and the Spatialities of In/Securities in US Cities,” In/Security 54, no. 2 (2016): 13–23; and Lindsey Dillon and Julie Sze, “Equality in the Air We Breathe: Police Violence, Pollution, and the Politics of Sustainability,” in Sustainability, edited by Julie Sze (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 246–270. ↩

-

For an excellent book on Black breath, see Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016). ↩

Grace Sparapani is a writer, researcher, and editor based in Austin and Berlin. She is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas at Austin, where she specializes in contemporary art with a focus on video and performance as they intersect with trauma and medical narratives. She is a contributing editor at the Avery Review, and her writing can be found in Ed, Sofa Magazine, and frieze, among others.