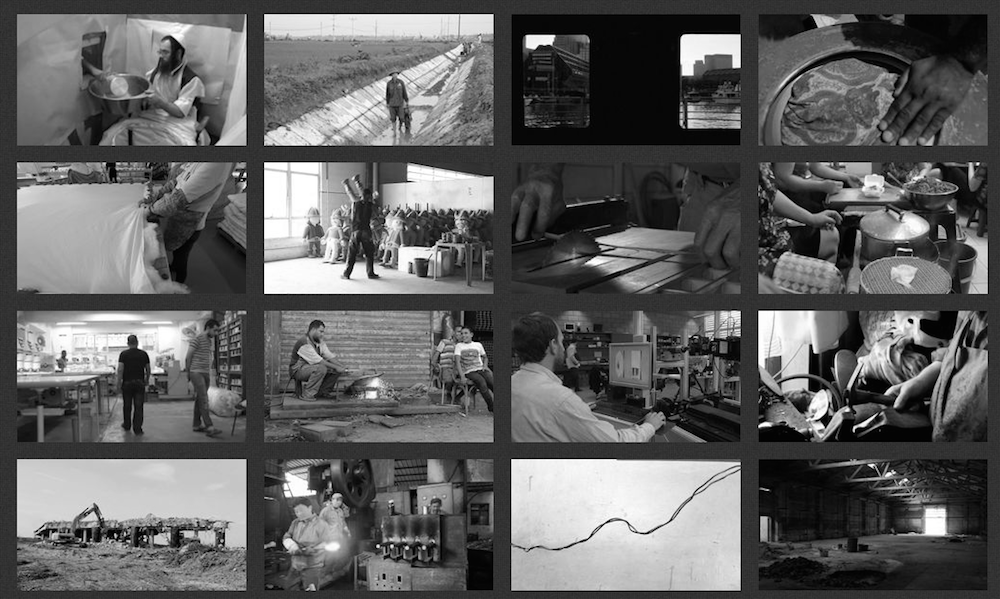

For one minute and fifty-four seconds, I watch a man in Lodz sort surgical instruments, his body a sequence of rehearsed movements. On the screen to my right, a man in Hangzhou plays a Chinese two-string violin in a subway corridor, the steep dip and rise of the honeyed melody resonating loudly, though he remains mostly invisible to commuters: 1:39. To my left, a dry cleaner in Buenos Aires meets my gaze as steam bellows up around him. 1:38. In the distance, Mary in Mexico City instructs a new employee in the art of paid phone sex, with a Blow Pop and some very honest dialogue, shorn by repetition of innuendo. After Mary comes Frida, a street performer in drag—eighty seconds of the great Frida Kahlo, painting a portrait of her painted self for the pocket change of casual spectators, the briefest of treatises on the play between regimes of visibility and invisibility. On a screen behind me, a woman harvests corn with a toddler tied to her back, 1:48; men in Rio cut leather samples in a windowless maze of cubicles and pass around a mate pot—each taking a sip from the bombilla, then passing it on, a daily ritual as quotidian and invariable as their work. A woman in Johannesburg trims stitching, her movements an economized theater of productive motion, a twenty-first-century “human motor,” labor power governed by quotas. Across the room a man on a moped navigates a dense grid of streets and alleys, delivering a jug of Calgon water to a gated home in Bangalore, the city and its gated addresses inscribed in his labor. In the film we see him only from behind. As I circle the labyrinth of screens, I recall the question posed with urgency by the belated Harun Farocki: How can I make visible what you have been trained not to see?

For Farocki, our habits and customs—Hume’s twin principles of association—are shaped by regimes of mediated viewing, which over time predetermine our perspective, framing not what but how we see, and influencing the causal inferences we draw as a result. These inferences shape our world, the realm of the imaginable, and plot the space of possibility. What remains unimaginable is denied legitimacy, erased, forgotten, refused entrance to the archive, that great “instituting imaginary,” as Achille Mbembe has described it, based on incomplete paradigms of visibility.1 The image, for Farocki, is an instrument of instruction; the political finds a body, or bodies, in images. In the opening segment of Nicht Löschbares Feuer (The Inextinguishable Fire), a film he made in 1969 that explored Dow Chemical’s production of napalm during the Vietnam War, Farocki described the influence of habit on perspective in this way: “At first you will close your eyes before the pictures, and then you will close your eyes before the memory of the pictures, and then you will close your eyes before the realities the pictures represent.” Farocki’s life in avant-garde cinema was a pursuit of intelligibility, each of his films elusive rejoinders to Debord’s declaration that all that is directly lived has become representation. He sought, in the words of Thomas Elsaesser, to “bring the unimaginable ‘into the picture.’”2 D.N. Rodowick, a scholar and longtime friend of Farocki’s, has described his films as “vision machines” through which Farocki constructed a new philosophy of the image, and offered new forms of what Rodowick terms “ethical looking.”3 “An image contains everywhere and on the surface all the information it will ever convey,” Rodowick argues, “nothing is suppressed or invisible. However, while every image presents a space of total visibility, every observer confronts the image from a perspective of limited intelligibility… Images have no ethics; only interpretations of them do, and these are inherently incomplete, contested, and contradictory.”4 “Where is war inscribed in images?” Rodowick asks. Everywhere.

I write this essay on the eve of the closing of the final exhibition, at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, of Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit (Labor in a Single Shot), curated by Antje Ehmann and Farocki. Ehmann, an artist, writer, and curator, and Farocki, an experimental filmmaker of the great Oberhausen generation who passed away in July of 2014, were partners and collaborators based in Berlin, the scene of their ambitious project’s final show. Over the course of three years, from March of 2011 to April of 2014, Ehmann and Farocki held a series of video production workshops involving more than 250 filmmakers in fifteen cities: Bangalore, Berlin, Boston, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Geneva, Hangzhou, Hanoi, Johannesburg, Lisbon, Lodz, Mexico City, Moscow, Rio de Janeiro, and Tel Aviv. According to the curators, the aim of the collaboration was to respond to the specific characteristics of each of the project’s 15 workshop cities and regions, and to grapple with the varieties of labor that structure their economies, and the lives framed by them. “Often labour is not only invisible but also unimaginable,” they write. “Therefore it is vital to undertake research, to open one’s eyes and to set oneself into motion. Where can we see which kinds of labour? What is hidden? What happens in the centre of a city, what occurs at the periphery?”5

What would it look like, they asked their collaborators, to return the factory in its many guises to the center of discourse today? In response, each workshop produced dozens of films, which led in turn to a series of exhibitions and to a Web archive of the project. The archive, comprised of 400 single-shot films, offers a counterpoint to the problem of increasingly veiled or “unimaginable” labor—its breadth and its arresting imagery are both formidable and beautiful.6 The guidelines, as Ehmann and Farocki conceived them, were simple: The task of each workshop was to produce multiple videos of one to two minutes in length, each taken in a single continuous shot. Cuts were strictly forbidden.

The method developed by the curators was borrowed from the single-shot films of the Lumière brothers, made at the end of the nineteenth century. Particularly important to the project is La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon), made by the brothers in 1895—the world’s first motion picture film, comprised of a brief but unwavering gaze at the activity that marks the end of the laboring day, as workers exit the Lumière factory en masse, achieving a differentiation of agency they lacked on the interior side of the property line. Following the proto-documentary style of the Lumière brothers, the films produced for Ehmann and Farocki restore the site of labor and workers themselves as central subjects of the picture, however briefly, and not without certain charged ambiguities and instabilities that resonate in unexpected patterns across the films. For the curators, the purpose of the method was to regain a critical openness to the image. “These early films,” they write, “made in a single continuous shot, declared that every detail of the moving world is worth considering and capturing… The single-shot film, in contrast (to documentary films today), combines predetermination and openness, concept and contingency.”7

The uncut gaze of Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit functions here in two very distinct ways: It disassembles certain perceptual paradigms that lead to familiar erasures, while simultaneously placing the facticity of its subject into crisis through a process of subtle abstraction. Nora Alter, in an essay on Farocki, terms this a technique of sub rosa persuasion.8 Repeat a word enough times and it begins to loose its meaning, the line connecting signifier to signified fades; this exercise in disassociation is one more argument for the tenuousness of intelligibility, and the complexity of documentary observation, recombination and representation. The exhibition, designed by the architectural firm Kuehn Malvezzi, is a warren of fifteen floating screens, each representing a city, on which half a dozen two-minute films run in loops; the spatial strategy plays its own visual-semantic game of disruption, splitting perception along intersecting lines of sight. An experience like the “I” dissolving in a hall of mirrors, unmoored by its sudden multiplicity, this laboratory of single-shot films produces a powerful sensation of estrangement. Both the architecture and the Web archive become their own “vision machines,” models of apprehension born in the act of recombination and displacement—the repeatedly splintered specter of labor an important allegory for the masking of labor power and the disappearance of class struggle over the course of the twentieth century.

The final exhibition, which opened on February 26 in Berlin, was planned to commemorate the 120th anniversary of La Sortie de l’Usine. This filmic trope has appeared before in Farocki’s work, and adds texture and dimension to this already richly complex and prismatic project. A thirty-six-minute film made by Farocki in 1995, Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik (Workers Leaving the Factory) opens with the original one-minute film from 1895, followed by a montage of similar scenes clipped from newsreels, feature films, and documentaries of workers exiting the proverbial factory gates—1975, in Emden, the Volkswagen factory; a return to Lyon, 1957; a Ford factory, Detroit, 1926; a Siemens factory in Berlin, 1934; workers changing shifts in the film Metropolis. As one watches these mannerist flows of egress, paradoxically the same and yet each qualitatively different, the narrator arrives at Farocki’s argument: “Never can one better perceive the numbers of workers than when they are leaving the factory. The management dismisses the multitude at the same moment; the exits compress them, making out of male and female workers a work force. An image like an expression,” she warns, “which can be suited to many statements. An image like an expression, so often used that it can be understood blindly, and does not have to be seen.”

Back in Berlin, at the final stop in a long exhibition cycle, which began in February of 2013 in Tel Aviv, I watch an anchor in Hanoi record the news for one minute and four seconds. The camera films her from behind and pans outward to reveal a series of odd and moving details that the stationary newsroom film will obscure: She is barefoot behind the dais, her dress more a smock or disguised robe than a suit, a huge can of hairspray and an empty water glass to her left, amid papers in disarray, just out of range. She reads facing her filmed reflection—another refracted self: She sees only the controlled version; we see the disorder that surrounds it. This play between framed, or staged, stability and the more truthful uncertainty that paradoxically constitutes the groundwork for the frame, or—in Ehmann and Farocki’s lexicon—the tension between the visible and the invisible, between political fantasy and the vulnerable fact, plays out in each loop of films on each of the fifteen screens. As I watch the news assemble in Hanoi, I am reminded of a line by Borges: “We were, without knowing it, inside a fiction.”9

Each film in this collaboration reads like an essay, and each, like the global collaboration itself, performs an act of heresy like every work of Farocki’s—a dismantling of “the orthodoxy of thought” that reveals unstable truths and disavowals. “Through violations of the orthodoxy of thought,” Theodore Adorno once wrote, “something in the object becomes visible which is orthodoxy’s secret and objective aim to keep invisible.”10 In the maze of screens in Berlin I encountered labor’s uncanny and the machines that obscure it—the idiosyncratic routines of capitalism hidden from view. Each filmmaker has responded differently to Ehmann and Farocki’s interest in the mediations by which narratives acquire their stability, or facticity—but running through each film like a red thread is the desire to upend power’s operative selectivity of images, the mediated web of narratives that form political memory, what Farocki in a 1993 essay called “the industrialization of thought.”11 A wonderfully complex archive of work, Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit produces an intelligibility of the image premised on lacunae and elisions—critical voids that do not, to recall Foucault, create deficiencies; they do not constitute lacunae that must be filled, but function rather as “the unfolding of a space in which it is once more possible to think.”12

-

Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton, et al. (Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 2002), 19. ↩

-

Thomas Elsaesser, ed., Harun Farocki: Working on the Site-Lines (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 17. ↩

-

D.N. Rodowick, “Eye Machines: The Art of Harun Farocki,” Artforum, vol. 53 no. 6 (February 2015): 197. ↩

-

Rodowick, “Eye Machines,” 195. ↩

-

Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki, quoted in the graphic works that accompany each exhibition; a similar statement appears on the project’s website: www.labour-in-a-single-shot.net. ↩

-

The categories by which a user is allowed to sort the Web archive’s content—blue, green, grey; cleaning, construction work, garbage, hot, teamwork, traffic, among other options—introduce instabilities that unsettle the archive’s field of visibility. These non-corresponding taxonomies of labor produce a rippling effect of uncertainty that can be traced back to the conflict internal to the archival act of naming, a parable of their disappearing subject in live time. ↩

-

Ehmann and Farocki, this excerpt appears on the project concept page of their site: www.labour-in-a-single-shot.net. ↩

-

Nora Alter, “The Political Im/perceptible in the Essay Film: Farocki’s ‘Images of the World and the Inscription of War,’” New German Critique 68 (Spring/Summer 1996): 169. ↩

-

Jorge Luis Borges, “When Fiction Lives in Fiction,” in Selected Non-Fictions, Jorge Luis Borges, ed. Eliot Weinberger, trans. Ester Allen et al. (New York: Penguin Books, 1999), 160. ↩

-

Theodor Adorno, “The Essay as Form,” in Notes to Literature, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson, vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 23. ↩

-

Harun Farocki, “The Industrialization of Thought,” trans. Peter Wilson, Discourse, vol. 15, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 76–77. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New York: Vintage Books, 1970), 342. ↩

Hollyamber Kennedy is a doctoral candidate at Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Her dissertation is titled Welt bildend: Architectures of Security and Design Reform Modernism in Germany and Beyond, 1848-1930.