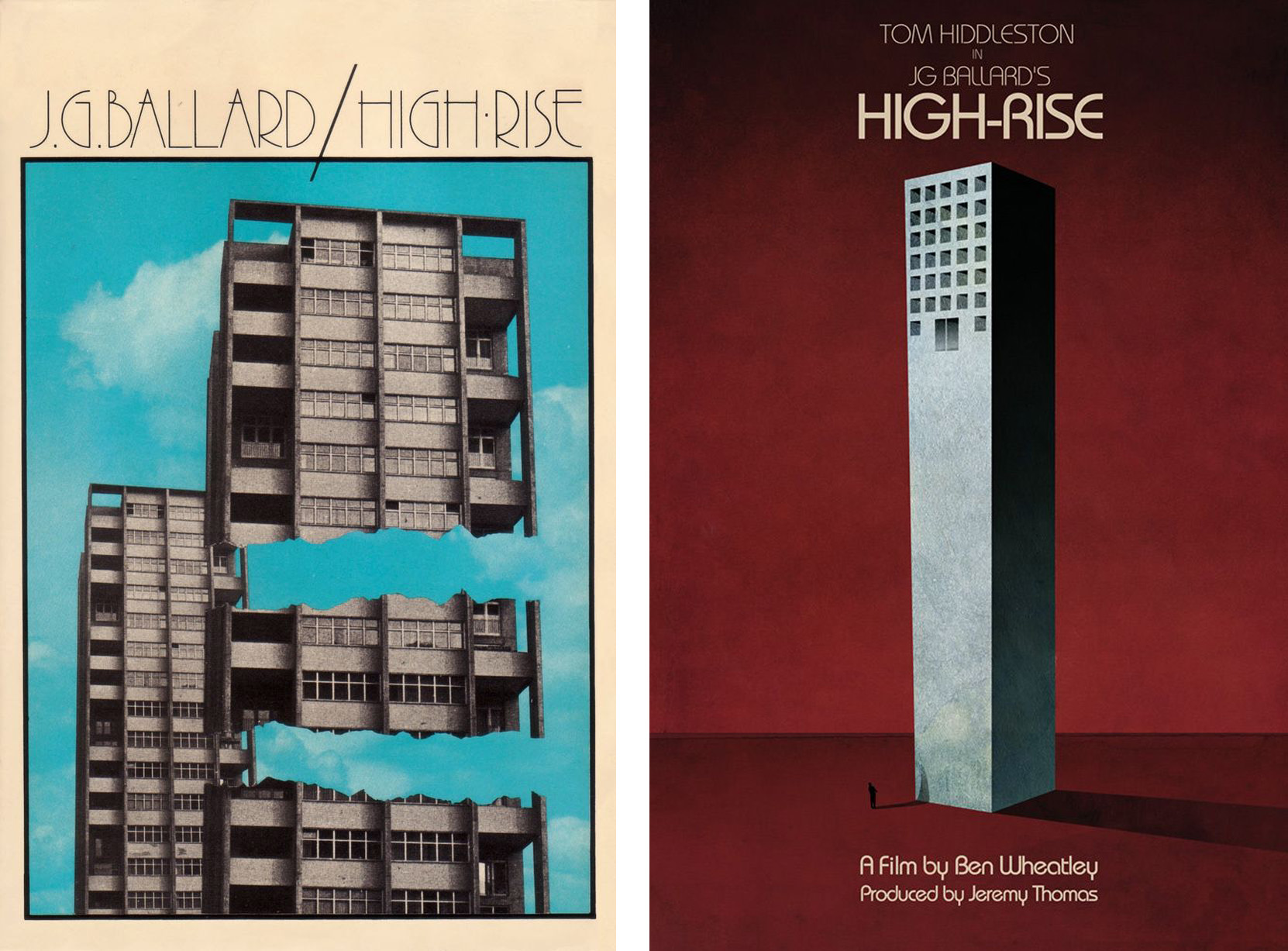

A model collection of urban professionals moves into a luxury residential high‑rise; within the vertical confines of their exclusive new world, they soon descend into madness and savagery. The plot of J. G. Ballard’s impeccable novel High-Rise, published in 1975, is certainly one that deserves, and perhaps demands, to be turned into a film. Yet it took forty years for this film to be made.

Adapting a cult novel must be intimidating. There is no doubt that the audience will lie in wait, their beloved copy on their laps, ready to lash out at any artistic license taken in the film. Whether or not this was a factor at play, the director of this long-awaited adaptation, Ben Wheatley, chose to follow Ballard’s text with almost religious devotion. From the setting to the narrative structure, his film is an effort to mirror the novel—a quite successful one in many respects.

An inebriating cocktail of sex and death drives, the distinctly weird atmosphere of Ballard’s novel is well conveyed in the increasingly orgiastic parties that are thrown on the tower’s every floor. These form the key scenes by which the exaggerated sociality of the tenants is captured; in symmetrical opposition, the recurrent elevator shot, in which the central character, Robert Laing, is surrounded by his own mirrored reflection, is where the profound isolation of each resident is revealed. Throughout the film, an agile cinematography moves swiftly through the building: close shots that brush over skins and concrete evoke the essential tactile dimension of the book, and while it only rarely ventures outside, the camera does so to capture highly dramatic shots of the tower’s immoderate stature, as it rules over a desert-gray landscape.

Purposely designed for its appearance on-screen, the architecture of the high-rise is a convincing embodiment of Ballard’s literary scheme. The colossal tower, with its top ten floors leaning out like the suspended event of its own collapse, stands adroitly between plausible reality and fictional hyperbole. Thick concrete columns with a reverse-pyramidal shape pierce abruptly through every interior space: a dubious structural system, nonetheless efficient at conveying a sense of oppressive weight. In accordance with the novel’s plot, the director is careful to leave the role of the protagonist to the high-rise itself, the appearance of which has been given the most attention. Inside its stylish entrails, the other characters are credible as they collectively enact an inescapable shift from normal to feral. In short, the film is, indeed, faithful to the book.

Perhaps too faithful. Like most of Ballard’s writing, the original novel anticipated a future all too near—so near, perhaps, that it could bleed into the present through the very pages that described it. Essentially, the Ballardian effect arises from a blurring between now and soon (the author famously declared that his keenest interest was “in the next five minutes”), which raises the question: why is this new High-Rise still set in the seventies?1 Undoubtedly this artistic choice makes for an eye-pleasing movie: sexy, vividly colorful, carrying an almost exotic cachet by transporting the viewer into a vintage past. But let us speculate on a different movie, one that would be faithful not so much to the novel’s decor as to its critical significance, as a razor-sharp commentary on the psychopathology of the urban condition at the time of its release.

A Historical Realignment

Six months earlier, when he had sold the lease of his Chelsea house, and moved to the security of the high rise, he had travelled forward fifty years in time… 2

Several examples of postwar architecture in London could have inspired High-Rise; they are worth revisiting in order to understand the particular cultural and political turning point that the novel grasps so vividly.

As modest as its design was, few high-rises had a more profound impact on the British architectural landscape as Ronan Point. On May 16th, 1968, merely three months after the first residents had moved in, a moderate gas explosion on the eighteenth floor of this prefabricated tower block brought about its partial collapse, killing four and injuring many. A forensic examination revealed numerous defects in the construction process, raising worries about the thousands of other tower blocks that had been hastily built over the previous decade to house a growing working-class population. A highly publicized event at the time, this single collapse precipitated a U-turn of Britain’s social housing construction policy, effectively sounding the death knell of what had been a widespread civic endeavor.3 Major projects initiated before this event went up nevertheless, such as the thirty-one-story Trellick tower in North West London, inaugurated in 1972. Designed by Ernö Goldfinger, this cinegenic Brutalist icon is a new and improved copy of his earlier Balfron tower in Poplar, where the architect and his wife took residence in a top-floor apartment for two months, throwing champagne parties for the residents in order to gather feedback about the design.4 This story was directly transposed in Ballard’s novel, with Goldfinger becoming Anthony Royal—High-Rise’s ostensibly socially conscious mastermind with a flair for indulgence.

But the most important inspiration for the novel is arguably the Barbican complex. A self-contained world of over two thousand residential units integrating a wealth of facilities within its overtly defensive architecture, the Barbican stands out as London’s first example of a high-rise residential construction that is not, nor was ever meant to be, a social housing project. Commissioned by the wealthy Corporation of the City of London and constructed between 1965 and 1976, the complex was marketed to a nascent but affluent urban middle-class from the very outset of its conception, more specifically to “young professionals, likely to have a taste for Mediterranean holidays, French food, and Scandinavian design.”5 An eruption through London’s simmering skyline, the completion of its three forty-two-story apartment towers is exactly contemporaneous with the publication of High-Rise. In spite of a target of residents very different from that of previous high-rise tower blocks, the architecture of the Barbican exhibits the Brutalist language that had come to be associated with social housing—although a uniquely sophisticated version of it, enabled by the massive investment of resources that went into its construction. As such, the Barbican marks a hinge, between the urban architecture characteristic of the postwar economic boom years and an emerging, thoroughly new urban condition, which Ballard would seize as the raw material of his novel.

For its epoch, the Barbican was a dice throw, an aberration, but that proved a highly successful one. In fact, it would take decades before the financial and cultural conditions would again align to launch the construction of luxury residential high-rises in London. It nonetheless crystallized a radical shift: the typology of the high-rise passing from a cost-effective instrument for public housing projects to a highly profitable one for private developments; from the hands of the state to those of the market. Across the Western urban landscape, the old meaning of the high-rise typology had first to be killed—with the ritual of its demolition having been famously proposed as the trigger of the postmodern period in architecture—before it could be resurrected around the turn of the millennium as a viable option of living for the urban rich.6 In this perspective, High-Rise bears witness to the astonishing literary intuition of Ballard, who projects and unravels the entire scheme of the neoliberal urban order to come, the moment its first tremors could be felt.

To this bourgeois appropriation of the high-rise, a typology of living that had come to define architectural modernity while essentially employed to accommodate the poor, corresponds another role swap of much broader significance. Up until the seventies, the champions of capitalism had traditionally adopted a politically conservative stance, anchored in a past that grounded their privileges; in contrast, discourses of socialist inspiration were essentially turned toward the future, as the terrain where social progress could be realized. One of the coups of neoliberalism, and a key factor of its swift rise to global hegemony from the mid-seventies onward, has been to invert this classical disposition: to occupy the future as its primary ideological terrain, and to start selling it in shares.7 Nothing would ensure a more durable reproduction of class relations than turning progress itself into a commodity; one could say that the Left never truly recovered from this shattering blow. As the fizzy utopianism of the sixties met one deception after another, the seventies inaugurated an era of cultural disillusionment.8 The notion of progress shifted to signify mere technological modernization, while social progress largely came to a halt. In return, the Left slowly grew suspicious of both the future and technology altogether. To this day, critical and oppositional stances in the West seem largely haunted by a form of nostalgia—for past brilliance, for lost traditions, for simplicity; all the while they have become less and less capable of conceiving the future as an open horizon.9 In a way, the director’s decision to shoot this new High-Rise in the seventies can itself be read as a symptom of this cultural pathology. In this regard, the final shot on a globe-like soap bubble with Thatcher’s voice rising in the background feels like too little, too late.

An Enduring Diagram

The high-rise was a huge machine designed to serve, not the collective body of tenants, but the individual resident in isolation.10

When questioned about the setting choice, Wheatley answered, “We set it in the seventies because there are elements of the book that would be destroyed by modern life—specifically, social media ruins a lot of stuff.”11 But would a contemporary High-Rise be anathema to the book? Was there truly no alternative?

A first and obvious counterpoint is that the luxury residential high-rise, a typology of building that Ballard had to almost entirely imagine at the time of his writing, has now become a well-established reality, one rising throughout global cities, London notably included.12 When set against other well-known trends—the multiplication of gated communities across the urban fabric worldwide; the accelerating rate of privatization of urban land, property, and development; the wealth inequality gap that is widening across all urban societies with a market-driven economy—the ongoing mushrooming of luxury high-rises can itself be framed as an index of an increasingly planetary neoliberal urban order.13

Yet there is much more to that. Contrary to a common interpretation, the novel is not an allegory of class struggle crystallized into a piece of architecture. The high-rise does not stand for something else; it is not a metaphor for society as a whole. The high-rise is a machine—a machine for living separately. The three levels of separation it operates on are all explicitly described in the novel. First, the high-rise organizes the secession of a particular social group from the rest of the city, as the new residents purchase their way into this “vertical city.”14 Then, it subdivides this “virtually homogenous collection of well-to-do professional people” into “three classical social groups” (lower, middle, upper classes), each of which is represented by prominent design features, such as the “10th floor shopping mall” or the “restaurant deck on the 35th” that act as social boundaries across the tower.15 Finally, the high-rise further isolates each resident in his or her own compartment at the same time as it puts them all in obscene proximity with one another. Lesson learned: repetition exacerbates difference. Akin to the workings of the regular urban grid, the multiplication of quasi-identical cells establishes a system of generalized equivalence that, combined with the purely hierarchical logic of their vertical stacking, has the effect of fostering transactions, competition, even conflict among the population that it partitions. As such, the high-rise also constitutes an “abstract machine” or diagram.16 It encapsulates what could be described as the general logic of neoliberal urbanism: the continuous generation of ever more subtle differentials across a spatio-economic whole, itself assembled through the expansion of a rigid frame of reference that establishes the terms of their trade.17 Modernized urban life wouldn’t destroy anything of the novel, except its extraordinary character—as Ballard’s prescient plot has now become a norm.

Far from breaking this scheme, social media constitutes its seamless extension, its computational upgrade. The always identical and infinitely reproducible format of a profile is another system of generalized equivalence, by which a social media platform structures a self-contained framework of exchange and cashes in on every transaction of capital, whether social or monetary.18 As infrastructures of private sociality, both the high-rise and social media establish a dialectical and reversible relation between connection and separation. Let us not be duped by the Californian ideology: even when using social media, one is never fully connected to the whole world but only to a particular social cluster, a particular cross-section of reality; the more one dwells within it, the more people and things that are out of it tend to disappear.19 For this reason, transposing High-Rise into the twenty-first century wouldn’t have automatically undermined the isolation of characters that is so central to the plot. On the contrary, the interpersonal, closed-loop form of modern-day communication can easily produce effects that are opposite to those it promises—including pushing a group of people to turn their back on the world they’re offered.

The backward gaze of the film is most frustrating when set against another strikingly anticipatory trait of the novel: actually, a primitive form of social media is already sketched out in Ballard’s High-Rise and plays a central role in the spread of violence throughout the tower-world.

The true light of the high-rise was the metallic flash of the polaroid camera, that intermittent radiation which recorded a moment of hoped-for violence for some later voyeuristic pleasure… The floors were littered with the blackened negative strips, flakes falling from this internal sun.20

“Every time someone gets beaten up about ten cameras are shooting away.”

“They’re showing them in the projection theatre,” Jane confirmed. “Crammed in there together seeing each other’s rushes.” 21

The intersection of violence and mediation is a theme dear to Ballard. High-Rise in particular explores the effect of an accelerated image-making process, thanks to the affordability of portable devices such as the Polaroid and Super 8mm cameras, combined with an ease of circulation of those images among the concentrated residents of the tower block. At the center of the novel, a spiral is formed that will engulf the whole edifice: on the one side, the persistent gaze of the camera beckons more and more violence; on the other, violence is normalized by its constant mediation through the image.

Everything is there: the splintering city, the psychopathology of hyper-connected seclusion, the pas de deux of media and violence. Prefiguring its own extension by media, the diagram formed by Ballard’s fictional high-rise finds its most vivid actualization in our urban present. Surveying its amplified workings in today’s world of exclusive high-rises and interpersonal media networks would have been a great rationale for a film. It is not the one Wheatley chose to make.

A Future All Too Near

Even the run-down nature of the high-rise was a model of the world into which the future was carrying them, a landscape beyond technology where everything was either derelict or, more ambiguously, recombined in unexpected but more meaningful ways. Laing pondered this—sometimes he found it difficult not to believe that they were living in a future that had already taken place, and was now exhausted.22

Four decades after the release of the novel, one is forced to acknowledge that life in high-rises tends to remain, if not always civilized, at least out of the realm of all-out barbarity. Was the writer who in 1967 predicted Ronald Reagan’s election as US president wrong this time?23 High-Rise remains tastefully ambiguous about the image of the near future it projects. Two different, but arguably equally valid, interpretations could set us on track to imagine an alternative adaptation of the novel today.

A first approach to the high-rise’s drift into a Hobbesian state of nature would be to understand it as a break: of social conventions, of machinic processes, of commodity fetishism. Shielded within the tower, the “voluntary prisoners” of its architecture branch out of the city, no longer playing its rules, no longer playing their part.24 Ballard, one could say, stages an acceleration of the process performed by the high-rise—separation/competition—up to its point of rupture and beyond. Together with social restraint, technical maintenance is also interrupted: as a consequence, the high-rise-as-a-machine breaks down too. The environment that embodied the very idea of the future thus far collectively accepted recedes into a mere vertical bunker. The residents break through the veil of technology and discover the void that awaits them, “an environment built, not for man, but for man’s absence.”25 The outbreak of endemic violence and the emergence of makeshift tribal structures would hence mark the passage of this isolated social group past the limits of modern society, into the realm of savage freedom. As such, the novel would work as a cautionary tale: a warning, launched at the time of its publication, that the emerging combination of extreme individualism, secessionist urban impulses, and voracious appetite for visual shocks could bring the edifice of society to collapse—at least in localized pockets of the city. Radical opponents to the social system where the novel begins could also see it as a revolutionary moment, a liberation from an old system of oppression, and the opening of a new horizon of autonomy and liberty. Be that as it may, in this interpretation, the near future depicted in the novel would be located after the failure of our modernity.

Another reading is possible, which Ballard points to with clues scattered throughout the novel. The book opens with Robert Laing eating a barbecued dog on his balcony, reflecting back on the events that took place in the high-rise over the past months, “now that everything had returned to normal.”26 Looping back to the incipit, the last chapter provides more details as to the doctor’s new domestic normalcy: he rules over two sexual slaves whom he purposely hooked on morphine yet contemplates a return to teaching in his medical school. He remarks, “Life in the high-rise had begun to resemble the world outside—there were the same ruthlessness and aggression concealed within a set of polite conventions.”27 In this chilling perspective, rather than a dystopian future to be averted, the high-rise would be a literary figuration of our present. Indeed, at the heart of the novel is an observation of the process by which a community gradually knocks down all the social and moral boundaries it used to uphold. It is a survey of the emergence, through the joint effect of urban abstraction and media overstimulation, of a neurasthenic urban psyche, of the ultimate “blasé attitude” by which violence against our neighbor becomes tolerable, acceptable, normal.28 As such, the novel sketches out the key schema of structural violence: “It is not invisibility that allows violence to be repeated and reproduced, but repetition and reproduction that makes violence invisible.”29 The rapes, murders, and acts of cannibalism among co-tenants do not operate as projection of a reality toward which we could drift but rather as examples of how particular configurations of space, technology, and discourse are capable of making anything acceptable: such as the drowning of thousands at the maritime border of Europe, the shelling of entire neighborhoods in Gaza, or the recurrent event of a mass shooting in the United States. Anonymous and habituated, life goes on in the high-rise.

-

The much-quoted phrase first appeared as “I believe in the next five minutes” in Ballard’s prose poem “What I Believe,” published in Interzone 8 (Summer 1984). Available at link. ↩

-

J. G. Ballard, High-Rise (1975; London: Harper Perennial, 2006), 8–9. ↩

-

As a chain reaction, the amendments to the national building regulations that were triggered by the collapse of Ronan Point have been used as an important lever to bring about the demolition of hundreds of noncompliant council estates throughout the United Kingdom—in the large majority of the cases, without replacing the stock of social housing that those offered. See Norbert Delatte, Beyond Failure: Forensic Case Studies for Civil Engineers (Reston, VA: ASCE Press, 2009), 418. ↩

-

As reported by Alice Rawsthorn in “Child’s Play,” the New York Times, November 7, 2009, link. ↩

-

Peter Chamberlin, Geoffry Powell, and Christoph Bon, Barbican Redevelopment Report (1955), in Gail Borthwick, Barbican: A Unique Walled City within the City (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 2011)https://www.academia.edu/1298546/Barbican_A_Unique_Walled_City_Within_The_City. See also David Heathcote, Barbican: Penthouse over the City (London: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2004). ↩

-

See Charles Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1984). ↩

-

For a much more detailed discussion of this political realignment, see Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World without Work (New York: Verso, 2015), in particular Chapter 3, “Why Are They Winning? The Making of Neoliberal Hegemony.” ↩

-

This new cultural trend was perhaps no better epitomized than by the Sex Pistols’ lapidary anti-slogan, launched in 1977: “No future (in England’s dreaming).” ↩

-

To address, and to criticize, the nostalgic tendencies of the contemporary Left, Srnicek and Williams have coined the term “folk politics,” namely “a collective and historically constructed political common sense that has become out of joint with the actual mechanisms of power.” See Srnicek and Williams, Inventing the Future, 17. See also Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures (London: Zero Books, 2014); Franco Berardi, After the Future (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011); and Owen Hatherley, Militant Modernism (London: Zero Books, 2009). ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 10. ↩

-

“High-Rise is Not a Criticism of Post-War Architecture, Says Director Ben Wheatley,” Dezeen, March 25, 2016. http://www.dezeen.com/2016/03/25/high-rise-movie-not-a-criticism-of-post-war-architecture-interview-director-ben-wheatley ↩

-

“London’s Skyscraper Boom Continues with 119 New Towers in the Pipeline,” Dezeen, March 9, 2016. http://www.dezeen.com/2016/03/09/london-skyscraper-boom-continues-119-new-towers-new-london-architecture-report See also Carol Willis, “The Logic of Luxury: New York’s New Super Slender Towers” (research paper), CTUBH 2014 Shanghai Conference Proceedings. http://global.ctbuh.org/resources/papers/download/1952-the-logic-of-luxury-new-yorks-new-super-slender-towers.pdf ↩

-

Neil Brenner, ed., Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization (Berlin: Jovis, 2014). ↩

-

“Each day the towers of central London seemed slightly more distant, the landscape of an abandoned planet receding slowly from his mind.” Ballard, High-Rise, 9. “The Vertical City” is also the title of the fifth chapter of the book. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 10 and 95. ↩

-

See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 142: “The diagrammatic or abstract machine does not function to represent, even something real, but rather constructs a real that is yet to come, a new type of reality.” ↩

-

For a rigorous and elaborate definition of the “neoliberal condition” referred to in this essay, see Michel Feher, “The Age of Appreciation: Lectures on the Neoliberal Condition,” a series of six lectures given at Goldsmiths, University of London, 2013–2015, link. Additionally, arguments to support the proposed description of the spatial logic of “neoliberal urbanism” can be found in Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976); Jean Baudrillard, “Design and Environment,” in For a Critique of the Political Economy of Sign (New York: Telos Press, 1981); or Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City,” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995). ↩

-

For a thorough analysis of how contemporary “platforms” work, see Benjamin Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016). See also Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992). ↩

-

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture, vol. 6, no. 1 (1996): 44–72. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 109. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 161. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 147. ↩

-

J. G. Ballard, “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan,” in The Atrocity Exhibition (London: Johnathan Cape, 1970). ↩

-

“Exodus, or The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture” is the title of Rem Koolhaas’ 1972 Architectural Association Thesis (together with Madelon Vreisendorp, Elia Zenghelis, and Zoe Zenghelis). ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 25. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 7. ↩

-

Ballard, High-Rise, 146. ↩

-

While deeply exacerbated by the particular spatial and technological configurations of the post-industrial city, it is arguably the same problem that was raised, early on, by Simmel, in his canonical essay on the metropolis. See Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” [1903], in Simmel on Culture, ed. David Frisby and Mike Featherstone (London: Sage, 1997). ↩

-

Yves Winter, “Violence and Visibility,” New Political Science, vol. 24, no. 2 (May 2012): 195–202. Quoted in Lorenzo Pezzani, “Liquid Traces” (PhD Diss., Goldsmiths, 2015). ↩

Francesco Sebregondi is an architect, a research fellow at Forensic Architecture, and a doctoral candidate at Goldsmiths, University of London.