In the past few months, all of Southern California, and in particular Los Angeles, has been abuzz with a recent spike in cultural events that have captured the imagination of many within this culturally diverse region. And how is that? The organization Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA—PST for short—has, with more than seventy arts and cultural institutions, brought a broad and diverse exploration of Latin American and Latino art to the Southland. The program has been running since September 2017 and will officially continue through January 2018, though many individual institutions will run their exhibitions after that point.1 If you live or have been to LA recently, perhaps you’ve caught wind of this unprecedented event. After all, stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic, it’s hard to miss the banners hanging from every lamppost over every boulevard in this beloved autopia. With shows varying from topics like pre-Colombian goldwork, alternative arts spaces in Mexico City, and Chicano muralism in LA and throughout the southwest United States, the organizers have announced on these ubiquitous banners: “THERE WILL BE ART!”

Of the many PST shows, I’d heard numerous opinions from architects and architectural historians regarding Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). My curiosity was piqued. Along with a friend who, like me, had received architectural training, I decided to visit LACMA on a particularly hot Saturday afternoon. On weekends the museum can be a bit packed. We hit the crowd, slowing our entry but allowing for some people-watching—much to my delight, a noticeable number of Hispanics and Latinos were present.2 When we arrived at the window, it was the usual scramble to find out what discounts would get us out of paying the steep twenty-dollar entry for residents of LA County.3 My friend is a grad student at USC but had misplaced his ID. There was no need for it, however, since the middle-aged Chicana vendor at the window gave him the discount anyway on account of his Café Tacvba tank top. As I handed her my student ID and debit card, she quickly said that I could enter free of charge. Apparently, a piece of plastic with the Bank of America logo is the golden ticket for events affiliated with Pacific Standard Time.4 How thoughtful of the big bank, no? I mused on the fact that BofA has for years handled a large Hispanic and Latino clientele and then recalled a slew of articles on said financial institution’s habit of exploiting working-class and immigrant Latinos through discriminatory and predatory lending practices.5 Does free admission qualify as making amends?

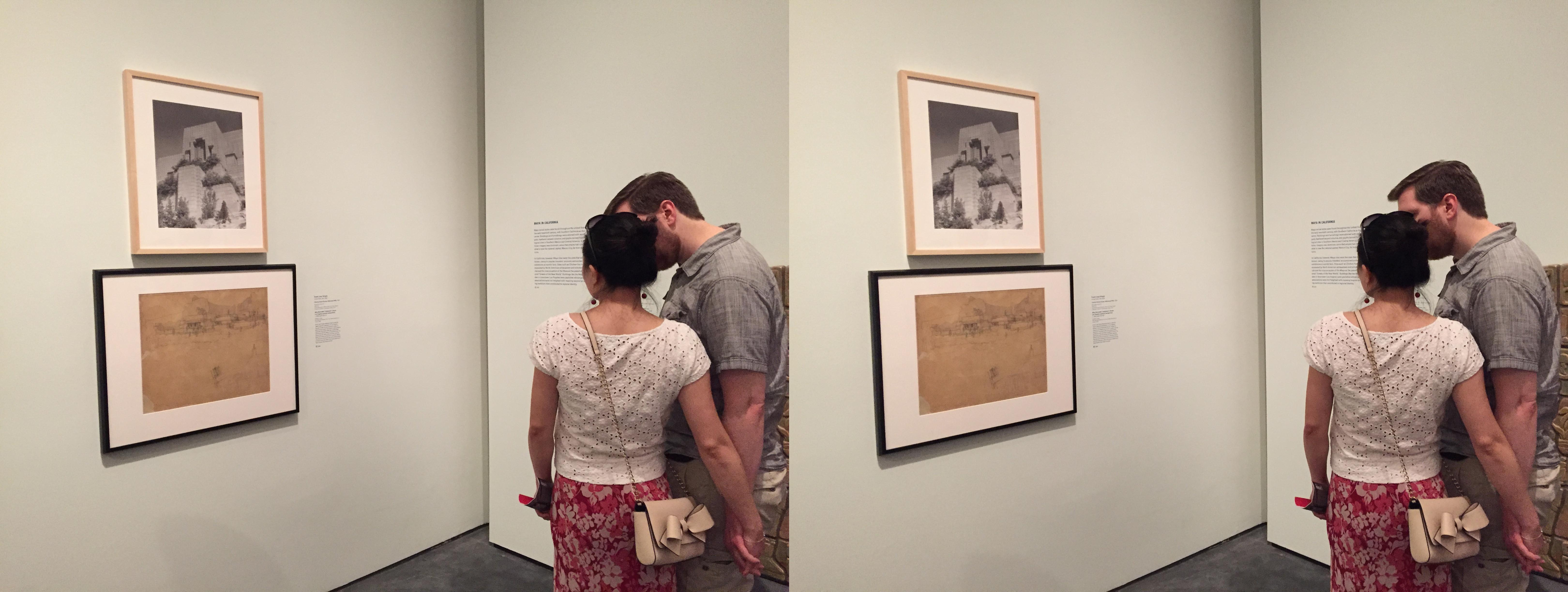

I attempted to put that thought aside for a moment so as not to cloud my impressions of the exhibition. Upon entering the Resnick Gallery, located in the recently added wings designed by Renzo Piano, I was struck by a certain cohesiveness within the first two spaces dedicated to “Spanish Colonial Inspiration” and “Pre-Hispanic Revivals.” Together, they contained interwoven narratives of California boosterism, post-revolutionary Mexican reconstruction, the whitewashed romanticism of the Mission days, and the forging of national and regional identities through ideas of mestizaje, indigenismo, and integración as well as a curious blend of neo-colonial, californiano, neo-Aztecan, and neo-Mayan aesthetics. The combination of strong narratives, compelling arguments regarding race, an even spacing of beautiful objects drawing observers into their orbit, and these rooms’ proximity to the entrance staged viewer interactions as varied as the viewers themselves. Among these were three guys in a cluster, standing a mile away from a mission-style chair, table, and poster advertising travel to Catalina, gesturing and talking loudly in a manner reflective of a rehearsed struggle with their own naco-ness; the twentysomething-year-old boyfriend softly mansplaining to his girlfriend the drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis house; the middle-class wife looking long and hard at that Talavera-ware bowl. Intently enough so that she, with husband in tow, might just take a stroll to the LACMA gift shop and pick up a set of Talavera tile coasters for eight dollars a pop.

If the interactions between viewer and art were seemingly forced or shallow in these first areas of the exhibition, they were balanced by a particularly sympathetic dimension within the area dedicated to “Folk Art.” There appeared to be one or two medium-size Latino, possibly Mexican-American, families in the area. A few of the kids were staring at blue ceramic vessels while others joined my friend and me staring in amazement at a heartwarming documentary of Mexican artisan Pedro Linares, famed creator of the papier-mâché figurines known as alebrijes. It was in front of a large multicolored wool saltillo dating from the 1920s and dedicated to the Mexican president Álvaro Obregón, that I witnessed a not-quite-teenage Mexican-American boy standing beside his mother; they were wearing matching outfits of white tube socks, khaki shorts, and white long-sleeve T-shirts. She was in the process of explaining something passionately to him. I noticed the woman’s hands, moving up and down, pointed fingers thrusting left and right. She was describing the process of weaving on a loom to her son. Did this object harken back to her own recollections of textile work? Or perhaps back to memories of her mother, or an aunt, or even a grandmother back in Mexico who had been acquainted with such skills and techniques?

A particular crowd was congregated in front of the architectural works on display. The usual suspects. Twenty- to thirtysomething-year-old male designers dressed in black and piercing the drawings with their stares (often through black-rimmed glasses); casually intellectual strivers dreaming of wealth while looking at houses belonging to Mexico’s and Los Angeles’s impossibly rich and famous; individuals like my friend, who, passionate for architecture as well as his Mexican-American heritage, could be found photographing almost every drawing we came across.

And what architecture did we see? A fair amount, although this was not a show strictly about architecture. In the first two rooms, where it felt as if the narratives guiding the curation were more succinct and interwoven, I saw a stunning lithograph of Arthur Page Brown’s California State Building from the World’s Colombian Exhibition in Chicago (1893); a very fine watercolor elevation of Carlos Obregón Santacilia’s Centro Escolar Benito Juárez in Mexico City (c. 1924); a flat screen with headphones where we could watch Reyner Banham in his 1972 documentary on Los Angeles speak about “lots of ordinary people” with “unpretentious homes combining domesticity with the fantasy of their dreams,” “good domestic architecture” that in his view was less a style than it was a “frame of mind”; tantalizingly few images of Luis Barragán’s work, namely photographs of his house for Gustavo R. Cristo in Guadalajara (1929) and his iconic Cuadra San Cristóbal in Mexico City (1966–1968); a stunning cutaway interior perspective on trace of Federico Mariscal’s grand staircase of the Teatro Nacional in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (1930).

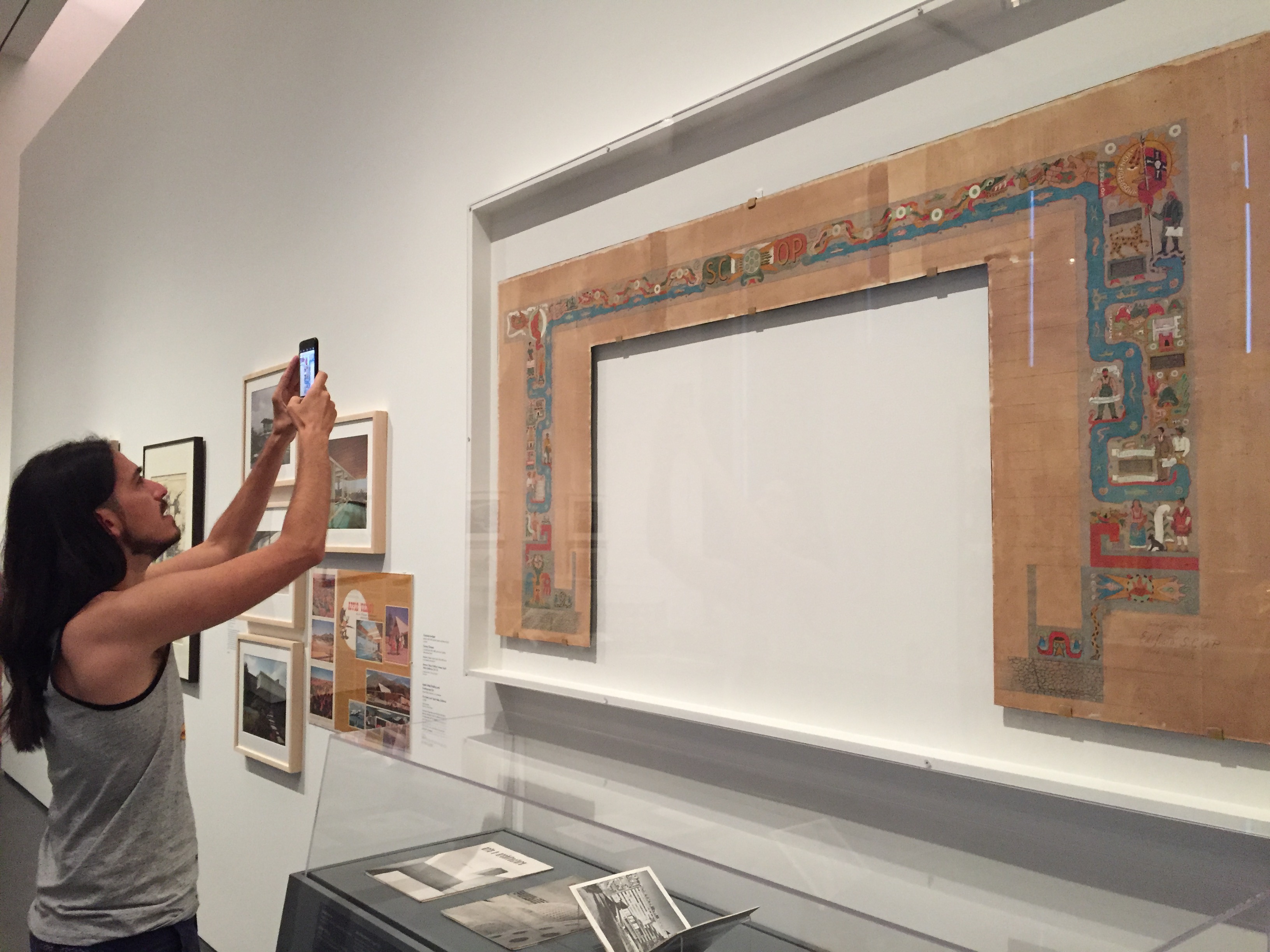

As we delved into the rooms dedicated to “Modernism,” the tightness of the narrative expanded, fractured, and took numerous parallel and incomplete paths, due less to any curatorial shortcomings than to the sheer difficulty of explaining the complexity and ambiguity of Mexico’s and California’s manifold postwar modernities. Richard Neutra’s work was put into formalistic dialogue with architectural projects belonging to Juan O’Gorman, Augusto H. Alvarez, and Francisco Artigas. Lamentably the conversation of images went no deeper than that, missing potentially fruitful opportunities of comparison between O’Gorman and Neutra’s individual projects for low-cost and functionalist school design and managing to ignore the social catastrophe that surrounded the latter’s utopic but unbuilt Elysian Park Heights project—a massive development ostensibly aimed at housing working-class families of Los Angeles that was shelved only after large swaths of the vibrant largely Mexican-American community of Chavez ravine were already purchased below market value and bulldozed.6 Interspersed throughout these formal comparative studies were books and catalogs by Ester McCoy and volumes of Arts and Architecture—objects that aided in the transfer of ideas and marketing of this modern image. To my personal delight, the curators included O’Gorman’s large color study for the mosaic mural cycle on the eastern façade of the massive Edificio S.C.O.P. (1953).7

I had entered the show, surely, with a few assumptions, mostly passed along from architects I know. Their comments were vague. There was a sense of disappointment that the show hadn’t been “more focused” or included more models—in other words, been solely architectural. Perhaps their expectations had been shaped by the exclusively architectural content and abundance of historical as well as specially commissioned models that had graced the halls of MoMA in their show Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955–1980? Despite that exhibition’s flaws, its overabundance of content was a real treat for its public—but let’s not forget that MoMA has a dedicated collection of architectural material and therefore a responsibility to curate shows that focus on only that.8 Or perhaps they were thinking of LACMA’s own California Design, 1930–1965: “Living in a Modern Way,” when the very same Resnick Gallery featured a life-size mock-up of a portion of the Eames House, filled with many of the building’s original furnishings.

But assumptions aside, I enjoyed the exhibition. Found in Translation was, in the end, an informative and intimate sequence of spaces dotted with elegantly curated mise-en-scènes, which in turn were made up of very beautiful objects that managed to harness a plethora of viewer interactions. Despite my general enjoyment, however, I did agree deep down that architecture was in some way lacking—or, more accurately, could have been displayed differently. As a cultural institution that seeks to serve the public in an educational and intellectual manner, LACMA’s display of architecture could have been more effective had it sought to engage local museum-goers in a deeper understanding of the complexities of architecture’s artistic but equally important technical, social, and discursive processes.9 Furthermore, returning to my initial observation on the relation between finance and public service, I wondered if it was somehow possible for the historical architectural objects on display to allow Latino, Mexican, and Mexican-American visitors in particular to reflect a little more not only upon the agency of architects but on the Mexican and Mexican-American culture on display within the historical as well as present processes that shape their built environments.

These musings prompted me to direct a series of questions to the show’s curators and researchers: Who was the intended audience for this exhibition? How was architecture being curated within a museum for art for this audience? And, last but not least, I wanted to know more about the efforts that are being made today by cultural institutions to attract the interests of Mexican, Mexican-American, as well as more general Latino and Latin-American viewers.10

I asked Staci Steinberger, assistant curator of decorative arts and design at LACMA, about whether architectural plans, working drawings, and sketches had been left out due to concerns by certain members of the curating team that the exhibition’s content had to keep in mind the museum’s general audience (as is often the case, and as I’d heard specifically about Found in Translation). She told me that cuts had been made all around due to the spatial constraints of Resnick Gallery and noted that LACMA is an institution that serves a “broader public,” which we shouldn’t assume is filled with “architecture experts.” It is the curator’s responsibility to treat these people as non-specialists. She stressed a need for legibility.11

Independent curator Ana Elena Mallet—a member of the team of researchers for the exhibition—reminded me that Found in Translation was ultimately treated as an art history exhibition. Echoing Steinberger, she expressed the inappropriateness of displaying “blueprints” in an art museum. As a person trained in architecture, I will admit that technical drawings are intended for a professional audience trained in their interpretation—qualities that can justly be viewed as resistant to the established conventions of art curation. But the comments of Steinberger and Mallet brought me to question: Is it conducive to society’s deeper understanding of art in its multidisciplinary plenitude that current art curators assume a particular reception to the more abstract and technical components of the larger artistic process that is architecture? Does the exclusion of these more abstract components representative of the artistic process and its discourse challenge LACMA’s mission in the “translation” of its collections into “meaningful educational, aesthetic, intellectual, and cultural experiences for the widest array of audiences”?12

The concern for comprehension seems to follow the exhibition’s general thematic of “translatability,” which brings me to my preoccupation with its curation in regards to its Latino and Latin-American audience. Steinberger, stressing an art exhibition’s need for legibility, immediately followed that by acknowledging that Los Angeles is a very diverse city. Because a concern for legibility is apparently tied to the observation of LA’s socio-economic, ethnic, and linguistic diversity, it is a place where things can easily get…lost in translation.

Cristina López Uribe, a professor of architectural history at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and researcher for the exhibition, offered an interesting perspective on the show’s direction. She observed that while the show was certainly addressing its Latino audience, that line of communication was perhaps less prioritized than reaching a wider as well as non-Latino audience, with relatively little or no exposure to the wealth of artistic and intellectual culture south of the border. This could be considered a classic progressive notion of public betterment and understanding via exposure—a rather noble pursuit of tackling ignorance, given our nation’s current political and cultural clime with its rising xenophobic, racist, and violent speech and actions against people of Mexican and Latino descent residing on either side of the border. However, I question its effectiveness toward this country’s more dangerously ignorant citizens—particularly given the demography of LACMA’s general audience.

Steinberger, on the other hand, felt that Latinos and Latin Americans were being more directly addressed. In defense of her institution, she challenged the impression of artistic vacuity that one might get from Pacific Standard Time’s catchy promotional slogan. She noted that at LACMA, there has been art—Latino, Latin-American, and Hispanic art—all along, as expressed in more recent exhibitions such as the currently showing Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici, and past shows such as Picasso/Rivera: Conversations Across Time (2016–2017), The Painted City: Art from Teotihuacan (2014–2015), Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film (2013–2014), Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico, which inaugurated the use of the Resnick Pavilion in 2010, and other major exhibitions going back decades.13 She stated that as a public institution representative of its community, LACMA had, through the efforts of Ilona Katzew, the curator and head of the Latin-American art department, greatly expanded its collection of Latin-American art.14

In our discussion of what was the intended general audience for Found in Translation, as well as for LACMA in general, Mallet pointed out how the characteristics of the “general audience” can shift. It is a well-known fact that California’s Latino population surpassed its white population in July 2014. Mainly boosted by expanding families within the second and third generations rather than by an influx of new immigrants, it is expected that the statewide Hispanic/Latino population will reach majority status after 2060.15 Within the city of Los Angeles, with an estimated Hispanic/Latino population already at 48.2 percent as of 2015, the majority status will be reached much sooner.16 This translates to a change in LACMA’s visitors.17

Such demographic changes will perhaps reflect the shift in color of Los Angeles’s wealth, though Los Angeles families of Mexican origin—the dominant group in the overall Hispanic/Latino ethnic category—currently have the lowest median wealth and liquid assets among LA residents, are least likely to be banked and to have savings, and overall have, along with African Americans, less than 1 percent of the wealth of white Angeleños.18 Despite the entrenchment of “whiteness” in this country’s systems of wealth and power, Mallet—a Mexican national—was optimistic that the tables will someday turn. Not citing a specific timeline, she opined that Latinos could very well come to have the lion’s share of money and power in the region. Someday, she noted seriously, they may even form a significant number of the trustees of LACMA.19 If this indeed comes to pass, then the museum’s collections and curatorial focus aren’t only changing to represent the interests of the general public. Rather, LACMA is following a more pragmatic approach that seeks to cultivate necessary audiences from within a shifting demographic while also taking into account its corporate governing structure that must anticipate the region’s shifts in socio-economic and political power.

Hers is an interesting point of view to consider. But I do feel that there is a certain irony in her general assertion when we consider the sponsorship of PST by Bank of America and my aforementioned free admission into the exhibition on account of my bank card. It is safe to assume that these sponsorships were a direct response to the changing demographics of LACMA and neighboring museums and are a means of cultural philanthropy in light of this bank’s history of abuse toward Latinos. If the curators and researchers of Found in Translation are going to speak of rising power in light of LACMA’s shifting curatorial focus, let us open up the conversation of empowering and how this institution could better utilize its presentation of arts and architecture to critically address a major program sponsor’s history of diminishing many a Latino’s financial and therefore physical presence in the built environment.

I recall that one of the basic premises of the exhibition—as stenciled onto the wall of the entryway in both English and Spanish—was to show the transfer of objects, styles, images, as well as techniques between Mexico and California.20 Why did many of the curators and research assistants of this exhibition choose to limit this exhibition’s audience to only a specific set of techniques—those of craft and artisanry?21 While I am aware of LACMA’s leadership in the realm of Arts and Crafts collections in the United States, and that the curators decided to focus the exhibition’s content toward portable everyday objects capable of transferring ideas, I must ask why the techniques of architectural construction (which in many of the architectures displayed are an amalgamation of scientific calculation as much as they are of craft) are not being displayed in the very portable objects of dialogue and knowledge transfer embodied by many construction drawings and sketches? Why, instead, must they be offered only via the final products of the design process and the public discourse of architecture—presentation drawings, postcards, and architectural journals? Such representations can at times offer only vague details of the technical process that brought that building to completion. The techniques of the architectural process are not always evident in the final product, as they evidently are in the woolen saltillo. Wouldn’t it have been stupendous if that anecdote of a Mexican-American mother and son that I shared earlier had instead been a discussion of the laying of rebar, the joining of steel members, or the finishing of stucco? These are technical details imbued with craft that, while abstract, are just as useful to the state of being of an objectified architecture as the visible warps and wefts are to one’s understanding of the finished object that is a tapestry.22

It’s here that LACMA might expand its current audience-building method of offering public programming that creates new experiences, deepens engagement, increases understanding, and is aligned with audience-development strategies. What if they also pursued a more progressive curatorial approach that recognizes the position of art, broadly defined, as an inspiration as well as a node of conjuncture for numerous creative and yes, technical, processes? The weaving anecdote shows that there were instances in which the exhibition had the power to provoke a personal relation to the techniques used in the creation of some of the objects—mainly those pertaining to craft—that were on display. This focus on techniques and their transfer, however, was in the end insufficiently balanced among the other art forms present. The presentation of techniques can provide a special exposure to museumgoers, especially if they are young and have a tendency toward the creative.23 Such exposure has the potential to lead to inspiration that in turn could lead toward a profession. In regards to architecture, the profession could someday give that boy and many other young children of Latin descent like him additional means to change their built environments—not only for their own interests but also for the communities that they represent. Despite the very real political, economic, and financial engines that exercise an overarching change upon our neighborhoods, cities, and regions—architecture, when in the hands of creative people from within a threatened community, can still mitigate many of the profound incursions upon the social and cultural dynamics of a still marginalized population. It is still a useful tool in the larger project of the creation of a more equitable society. And this is an urgent matter, because even given a general growth in the economic and political power of Latinos, there will still be countless Latinos who, due to their varied positions of class, generation, education, and access to reliable financial as well as cultural capital, will not have agency within the rapidly changing built environments of the new Los Angeles.

-

For more information on what Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA is, and what other exhibitions it has to offer, visit, link. ↩

-

Of course, the rapid scanning of a crowd for persons belonging to a very broadly defined ethnic and cultural category can be deceiving and can lead to generalizations. I can only cite my three decades of existence as the child of a Cuban-American woman, a resident of a primarily Hispanic/Latino enclave of Los Angeles and my travels through the Americas as my very imperfect radar. Conferring with my half-Mexican-American friend, however, we did generally agree that a broad spectrum of LA’s Latinos were out in force. ↩

-

For non-LA County adult residents, the cost is twenty-five dollars, link. ↩

-

Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA’s presenting sponsors are the Getty and Bank of America. ↩

-

These lending schemes affect a much broader racial spectrum and include unfair treatment of blacks and African Americans as well. For more information, please see: Tom Hamburger, “Bank of America is Accused of Exploiting Latino Immigrant Customers,” the Los Angeles Times, June 30, 2009, link; “Bank of America to Pay $335M to Settle Countrywide Case of Alleged Racial Bias,” PBS NewsHour, December 21, 2011, link; Sarah N. Lynch, “US Housing Regulators Accuse Bank of America of Discriminatory Lending,” Reuters, January 6, 2017, link. ↩

-

For more on the contested plans of development for Chavez Ravine and how a largely Mexican-American neighborhood was demolished first for public housing, and then for use as Dodger Stadium, see Nathan Masters, “Chavez Ravine: Community to Controversial Real Estate,” KCET: Lost LA, September 13, 2012, link. ↩

-

This was a particularly heartening image for me, not only due to my ongoing interest in Mexican muralism and the integration of plastic arts (integración plástica) but because I had assigned myself the task of photographing these murals days after the recent earthquake in Mexico City when it became apparent that the building they were on was severely damaged and slated for demolition. Word has it that the murals will be detached and saved. For more on this, see Anahí Gómez Zúñiga, “Los Murales que Han Resistido Más de dos Sismos, El Universal, September 9, 2017, link. ↩

-

For more on my perspective on the MoMA show Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955–1980, please read my critique, “Still Constructing,” Avery Review 8 (May 2015), link. ↩

-

It is perhaps useful to include LACMA’s mission statement here: “To serve the public through the collection, conservation, exhibition, and interpretation of significant works of art from a broad range of cultures and historical periods, and through the translation of these collections into meaningful educational, aesthetic, intellectual, and cultural experiences for the widest array of audiences.” See “Mission Statement,” LACMA: Overview, link. ↩

-

Here, I’d like to note that I was graciously helped by Staci Steinberger, assistant curator of decorative arts and design at LACMA; Ana Elena Mallet, Mexico City–based independent curator of modern and contemporary design; and Cristina López Uribe, professor of architectural history at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), in completing this portion of my review and journalistic investigation. With interests ranging from material culture, industrial design, and decorative arts; to graphic art, fashion, and popular culture; to modern architectural design, practice, and planning, I found their comments compelling as they reflected on the conflicts and resolutions within a multidisciplinary and transnational curatorial project. Despite my pointed criticisms of the show, I am extremely grateful to them for the time and insights that they offered me. ↩

-

Many of Steinberger’s comments adhere to LACMA’s 2009 strategic plan. Compare these statements with the institution’s commitment to “[provide] a varied, enjoyable, and educational experience for the widest possible audience (6); or its setting of objectives for “programming that increase engagement, accessibility, and visual literacy” (11). See Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Strategic Plan (Los Angeles: LACMA, October 2009), link. ↩

-

These questions likewise should allow the institution to reflect on questions related to its collection, its use among the community, and its setting apart from competing institutions. Steinberger has noted that LACMA has not historically focused on architecture archives, despite possessing architectural drawings in the collection, the active collection of furniture and other objects designed by architects, and the recent promised gift of John Lautner’s James Goldstein House. I would like to ask if this narrow interpretation of architecture could negatively affect the objectives in LACMA’s strategic plan to develop new strategic collecting areas, a proposal that includes expanding collections in architecture? Would a different take on the artistic value of the processes of architecture perhaps set the institution apart from competing with local architectural collections such as the Getty Research Institute; the Art, Design, and Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara; the Huntington Library; UCLA; and further afield, the Environmental Design Archives at UC Berkeley? This is echoed accordingly in the Hall and Partners’ Study, conducted in the summer of 2008, which specifically states LACMA’s need for “a unique and compelling point of differentiation” from its competitors (namely the Getty). See Hall and Partners, “Awareness and Visitation Study,” in Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Strategic Plan, 47, link. ↩

-

This concerted effort is reinforced in the strategic plan. The document states the objective to serve specific audiences including the Latino community. This ties in with LACMA’s “audience-centered approach” intended to “deepen visitors’ connections with art, draw visitors into more of the Museum, increase attendance, and attract new audiences” (11)—a critical endeavor in the past decade given the Hall and Partners’ Study’s observation that LACMA’s visitation since 2005 had softened due to “less frequent visitation among Non-Caucasians,” an issue that has been mitigated in part by a stable visitation by “Hispanics…potentially as relevant cultural exhibits have sustained their interest over the past year…” (47). See Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Strategic Plan, link. ↩

-

For more on Katzew’s role and mission at LACMA, see the recent interview, Chi-Young Kim, “Ilona Katzew, Curator of Latin American Art, Talks about ‘Pinxit Mexici’ and Building the Collection,” Unframed, June 19, 2017, link. ↩

-

Javier Panzar, “It’s Official: Latinos Now Outnumber Whites in California,” the Los Angeles Times, July 8, 2015, link. ↩

-

US Census Bureau, “ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Los Angeles County, California,” American Fact Finder, link. ↩

-

While the independent Hall and Partners’ Study that is included with LACMA’s strategic plan noted an increase in “Hispanic” museum-goers from 12 percent to 18 percent between 2005 to 2008 (49), LACMA’s own text in the highly ambitious strategic plan projected that Latino visitors would shift from 10 percent in 2009 to 42 percent of total visits by 2013 (15). See Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Strategic Plan, link. ↩

-

This data is cited from Melany de la Cruz-Viesca, Zhenxiang Chen, Paul M. Ong, Derrick Hamilton, and William A. Darity’s The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles—a 2016 comprehensive joint publication from Duke University; The New School; the University of California, Los Angeles; and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development that studies wealth, economic disparity, and race in the city of Los Angeles, link. ↩

-

While there are Latin Americans present within the board of trustees, namely Soumaya Slim, daughter of Mexican impresario Carlos Slim, and Gabriela Garza, an arts patron who has supported the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo Universitario de Arte Contempráneo, both in Mexico City, the board currently does not appear to have any local-born or LA-resident Latinos or Latin Americans. “Board of Trustees,” LACMA: Overview, link. ↩

-

At least that was the main thesis stenciled on the wall at the exhibition’s entrance: “MEXICO AND CALIFORNIA are irrevocably joined by geography, culture, and economics… People have moved back and forth between these two places for centuries, bringing objects, styles, techniques, and images whose meanings were shared as well as altered.” ↩

-

Likewise, LACMA’s youth and family-oriented pedagogical arm—its Andell Family Sundays—have apparently had, in the context of Found in Translation, very exclusive focus on these practices as evidenced by recent shows on weaving and the use of indigo in cloth dying. I criticize this not to detract from the cultural value of these practices. I highly value the potential sociopolitical value of craft and artisanry, but I also question the profundity of their socio-economic utility for citizens living within the increasingly unaffordable city of Los Angeles. That being said, the collective complaints that I have heard from many young architectural designers in regards to starting wages has also caused me to question the economic sustainability of the profession for young practitioners of less-privileged socio-economic backgrounds. Nevertheless, I remain firm in my assertion that the breadth of architectural training can eventually provide a foundation for numerous lucrative or empowering careers whether within the architectural profession or in the realms of planning, development, or public service. ↩

-

By “objectified architecture,” I refer to the treatment of the finished product of architecture as an artistic object, especially when decontextualized from its constructive processes and interaction with nonartistic disciplines. This objectification is manifested by final presentation drawings, models, and other representations related to the exposition of the overall architectural project. ↩

-

This is an argument from personal experience, as a lifelong visitor of LACMA who was inspired to follow a life of art, architecture, and now history from its exhibitions but who now calls upon it to do more and to expand its mission to the public of Los Angeles, and in particular to its young and marginalized citizens. ↩

Albert José-Antonio López is an architectural historian and current Fulbright-García Robles awardee living in Mexico City, where he is writing his dissertation on midcentury Mexican architecture, regional planning, and political society. He is a doctoral candidate in the History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art Program at MIT and holds degrees in critical, curatorial, and conceptual practice in architecture from Columbia University’s GSAPP, and in architecture from the University of Southern California. He is a native Angeleño.