The axiom freedom of the sea meant something very simple, that the sea was a zone free for booty. […] On the open sea, there were no limits, no boundaries, no consecrated sites, no sacred orientations, no law, and no property.1

The prehistory of the global market is the subject of dispute, however many scholars have traced it back to the sixteenth century and the age of colonialism, when the great sea empires and maritime nations arose.2 Among those, British, Dutch, Belgian, French, and Nordic states had their forces settled in more than half of the globe, while they were all based on the North Sea as their safe haven, a rather small body of water through which most of the world was conquered. Unlike southern European states, the North Sea countries shaped their overseas empires mainly through private trading companies (privateers), most important of those are famously known as British, Dutch, and Danish East-India and West-India Companies. Although they were private corporations, they were granted very peculiar jurisdictional powers: having the right to wage war, imprison and execute convicts, negotiate treaties, and establish colonies. Indeed, those privateers were freelance agents—not only to expand the maritime trade overseas but also to operate as an accepted part of naval warfare, taking part in expanding the empire at their own risk.

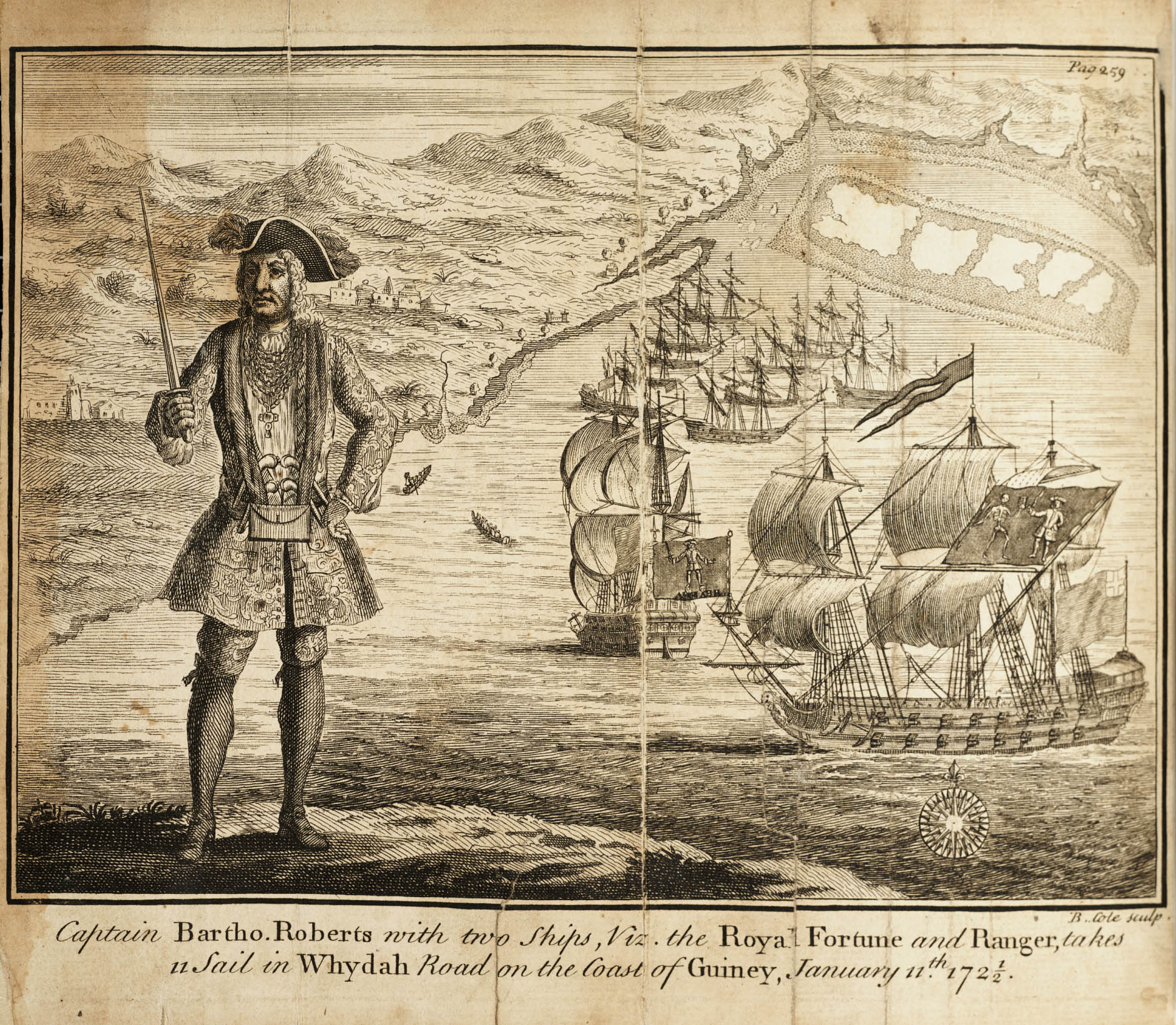

Unlike the pirate, the privateer holds a legal title, a commission from a government, a “letter of marque.” The privateer is entitled to fly a country’s flag, whereas the pirate’s only flag is a “black flag.” The legal performance of the privateer would be possible only by an employment contract, through which he would be granted authorization to conduct a raid. Nevertheless, this distinction, so clear and elegant in theory, was blurred in practice. Privateers often exceeded the limits of their licenses and navigated using forged letters of marque and, at other times, were armed only with licenses from nonexisting states.3 They reinterpreted the principle that the sea belongs to all and turned it into a space of liberation from moral and legal ties.4

Carl Schmitt, the German jurist, explains these juridical controversies in relation to spaces of land and sea in his book The Nomos of the Earth. He distinguishes privateers from state powers: private traders were viewed as an enemy by warring sea powers, not in the same sense as an equally sovereign state and not in the sense of an enemy in a war of annihilation against criminals and pirates. They were not outside international law; their actions were not illegal but precarious. As freelancers, taking the risks that came with not belonging to any land or nation, they navigated within the legal and juridical gaps of living and working on the sea. Schmitt adds, “their ventures were possible, because both operations occurred in principle in the no man’s land of a double freedom, i.e., in the non-state sphere: first spatially, in the sphere of the free sea, and second, substantively, in the sphere of free trade.”5 These peculiar conditions define the ways in which the private companies performed within the state of exception, both spatially and legally, to use the flexibility of sea law and economic relationships to outline their territories in foreign lands. The fundamental role of space in such history can be evaluated in two regards: the space of the naval vessel itself and the space of the sea. The former is reduced to the bare minimum space of living and working while the latter is a formless space of production, circulation, and distribution. Both were ex post facto geopolitical devices, materializing the pervasive relationship between political power, precarious laborers (privateers), and the maritime and continental territories.

Such obscured relations have mutated into new forms of life and space, and one might claim that the pirates and privateers of that era were not so dissimilar to contemporary hackers. A hacker is in fact a freelancer, a one-man company: an entrepreneur of him- or herself. The life of a hacker coincides with his/her own work: pure labor power at the service of a client. Like hackers, the life of privateers was based on a contract with a sovereign, proceeding at their own private risk. Their actions not necessarily illegal; rather, they thrive within a space outside any single national law. Remarkably, the North Sea has not only been a safe haven for pirates and privateers, but it is also the location of the most important hacker-friendly spaces: Sealand, the world’s smallest micro-nation.

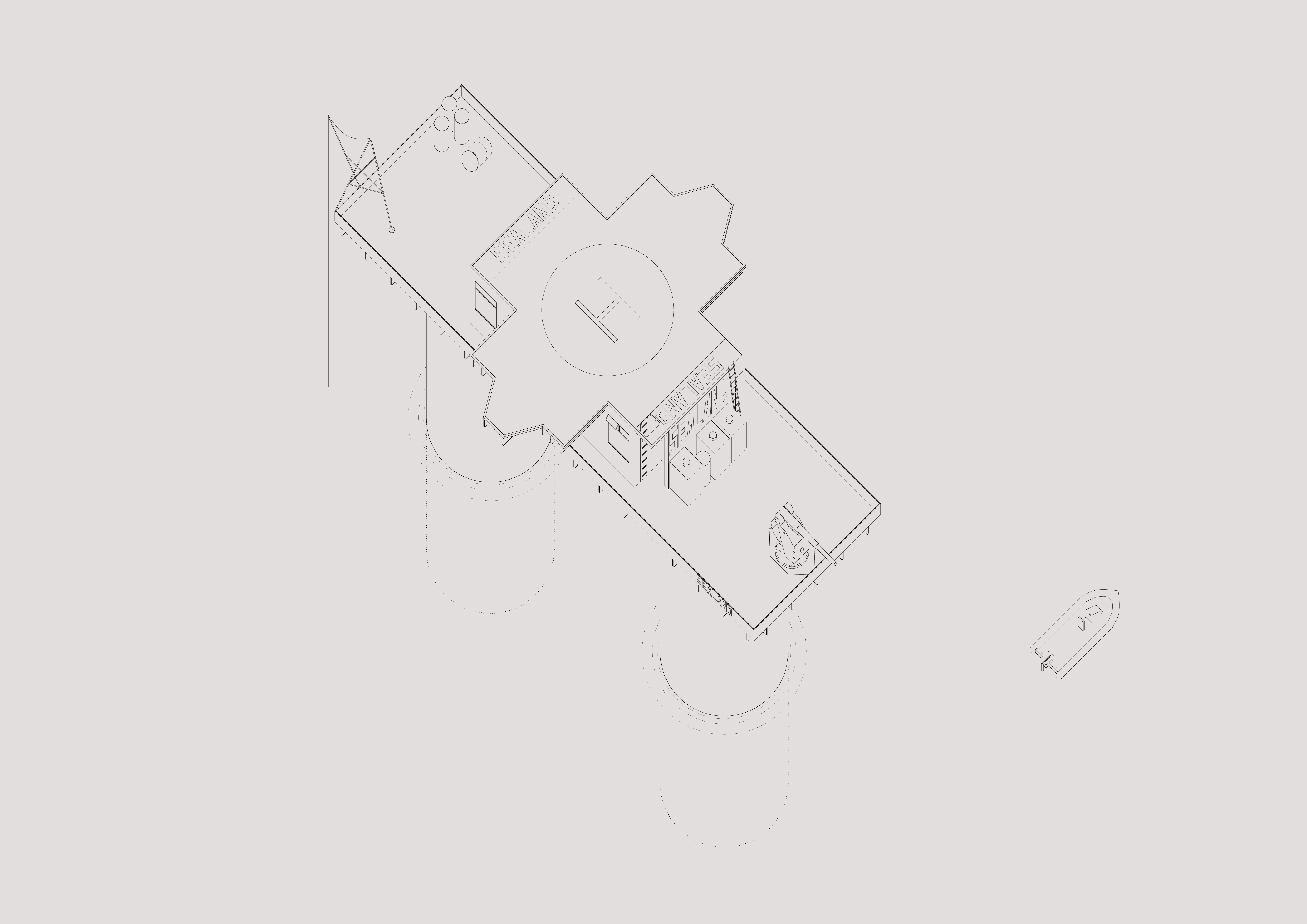

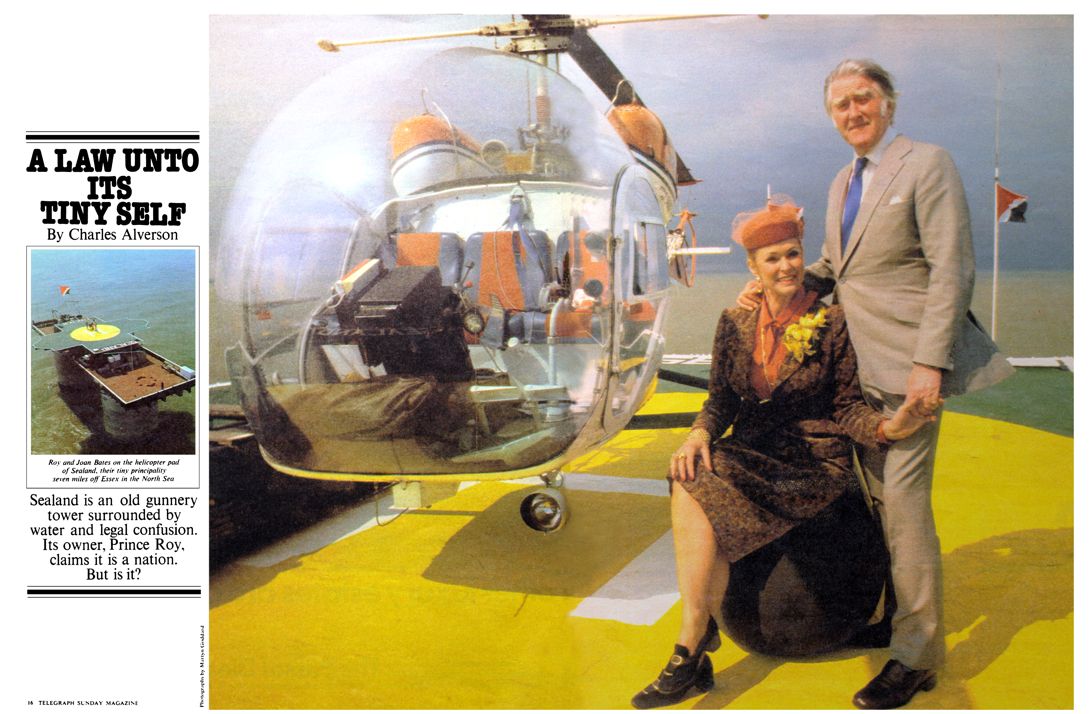

On February 11, 1942, some six miles off the coast of Suffolk, England, a British anti-aircraft defense platform was installed. In 1966 a former military major named Paddy Roy Bates and his crew occupied the platform, originally known as U1-Roughs Naval Tower. A few months later, Bates declared independence for the Principality of Sealand, a new country with a delimited border and an outlined territory—a sovereign state.6 In 1975 Bates formed a government, wrote a constitution, issued currency and passports, flew a flag, and presented a coat of arms marked with the motto E Mare Libertas (“From the Sea, Freedom”). The motto appears in all of Sealand’s official documents. In 1987 the United Kingdom extended its territorial waters to twelve miles, but since Sealand had achieved statehood prior to extension, Bates was able to maintain his country’s territorial waters. Nevertheless, the United Kingdom cautiously avoided answering the question of Sealand’s status for the next three decades. Official policy reflected a pair of negatives; on the one hand, Sealand was not part of the United Kingdom, but on the other, the government did not regard it as a state. What it was has never been entirely clear.7

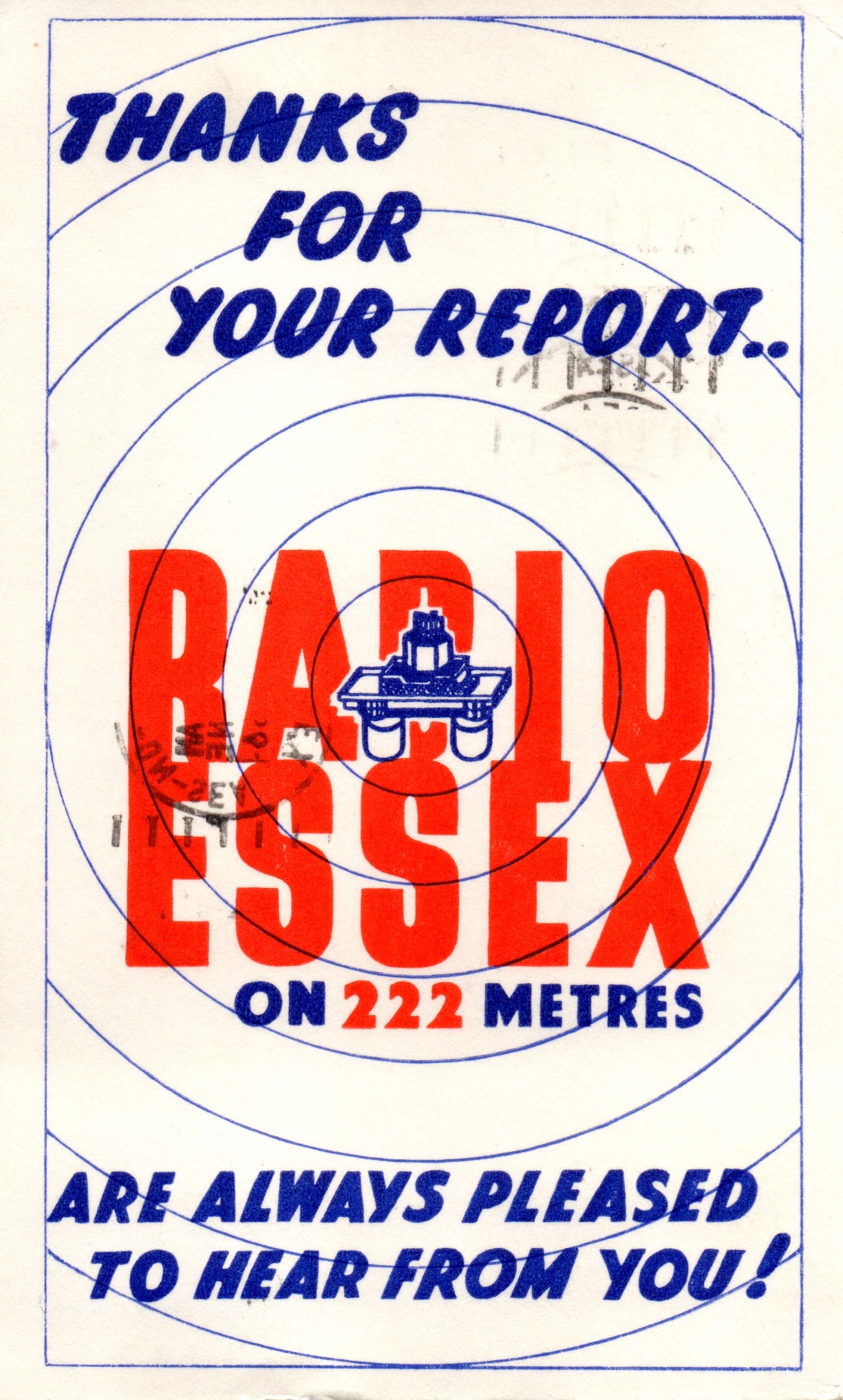

Bates’s 1966 occupation of the Roughs Tower was his second attempt to squat a long-deserted platform, and this longer history points to a vital connection between questions of territorial sovereignty and broadcast media. Bates and his family, together with his crewmembers, had occupied Knock John Tower in 1965, situated nine miles off the coast of Essex, and had founded the first Pirate Radio station (Radio Essex) in England, broadcasting a twenty-four-hour music program using the tower’s abandoned wartime equipment. Radio Essex changed its name to BBMS (Britain’s Better Music Station) in early 1966 and broadcast for two years.

In the mid-1960s, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) held a legal monopoly on radio broadcasting; anyone else transmitting radio signals to the public faced prosecution. Offshore pirate broadcasters proliferated accordingly, challenging the monopoly of the BBC by filling the public demands for pop and rock music. Pirate radio stations became massively popular at all levels of society, shaping a new generation’s musical taste that favored the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and the Who, among other yet-to-be legends of twentieth-century music.8 Among the first unlicensed stations, Radio Caroline was the most famous, based on five different ships broadcasting music from international waters in the North Sea. But Caroline soon suffered from the unstable nature of naval vessels—vulnerable to North Sea storms and juridical restrictions. Roy Bates took advantage of his military background—knowing the security level of the fort and having access to some military equipment—and occupied the Knock John fort to set up his own pirate radio in a more technically and legally stable condition.

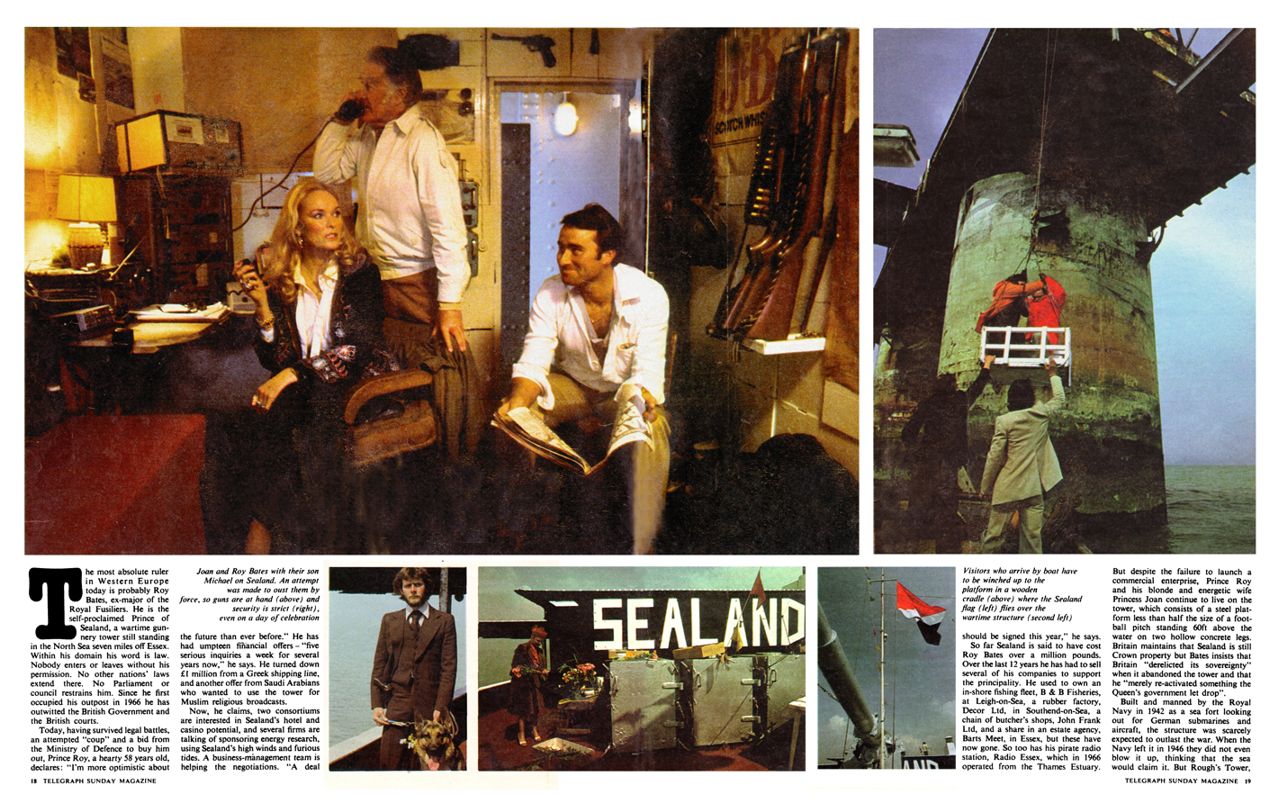

However, Bates’s plan did not work out as expected. In November 1966, Bates and his crew were forcefully removed from the fort and convicted of violating Section One of the Wireless Telegraphy Act of 1949. The charges were justified by the fact that Knock John Tower was located within the United Kingdom’s three miles of territorial waters, and Bates was found guilty of illegal broadcasting. In an interview following the verdict, Bates noted his future plans: “I hope to open a new station well out of territorial waters. I shall continue with this appeal and if necessary take it to the House of Lords.”9 A few days later, Bates and his crew squatted the Sealand fort located outside the UK’s territorial waters. The platform contained living quarters, offices, utility and mechanical rooms, and a radio transmission station.

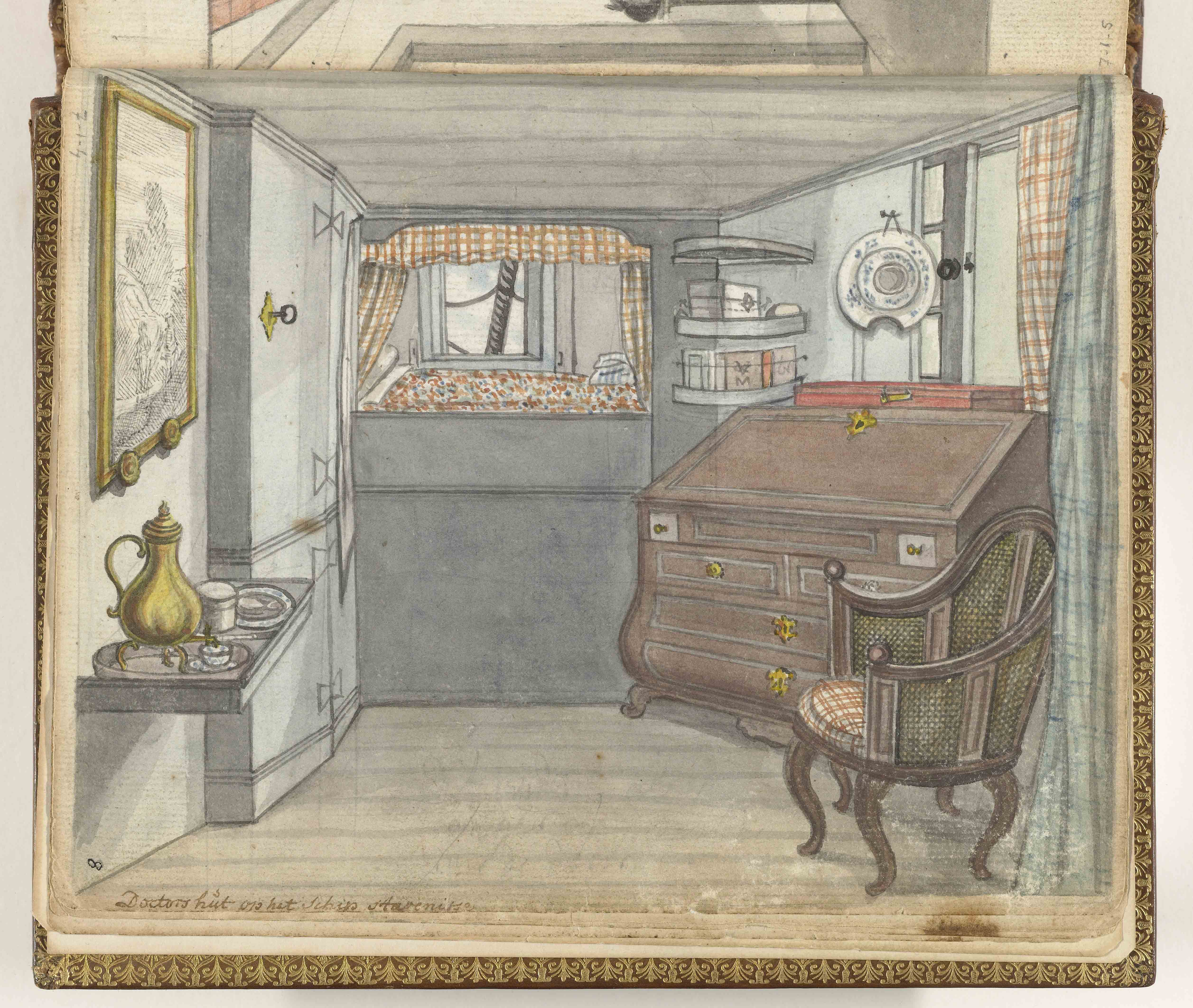

Despite the primitive working and living conditions offered by the platform, there was no shortage of young men prepared to endure the hardship for a DJ job. The Radio Essex had Michael Cane on board, who later changed his name to Martin Kayne when he joined Radio 355.10 For many years he was a columnist at Short Wave Magazine under his real name, Andy Cadier. Other figures such as Vince Allen, Dick Dixon, Guy Hamilton, and Graham Jones were also DJs. Life on board was rather precarious; the DJs frequently endured long periods at sea and often ran short of food and water. No alcohol was allowed and, for much of the station’s life, no television. With just a single man backing it financially, the station operated on a shoestring. BBMS proved to be a good training ground, and a number of the presenters later went on to jobs at larger stations. Before the BBMS could revive its programs on Sealand effectively, the Marine Broadcasting (Offenses) Act outlawed employing British citizens by pirate stations. Embracing the ancient legal doctrine of jus gentium, Bates declared Sealand’s independence on September 2, 1967. But many DJs had already left Sealand since, following the Marine Broadcasting Act, as UK citizens, they could have been subject to a criminal act if performing on the radio. They did not risk their lives to renounce UK citizenship and become Sealand citizens. Consequently, in 1967 BBMS went off the air due to insufficient funds and lack of staff.

The next years for Sealand resembled typical pirate ship’s ventures. The conflicts fought by Sealand pirates were not with sovereign states but with other pirates and privateers. Between April and June 1966, some of the Radio Caroline crew members tried to invade Sealand; Bates and his men repelled the boarding parties with Molotov cocktails and warning shots. Although the invasion attempts failed, Bates and his son Michael were arrested and charged with unauthorized use of a gun. However, the court threw out the case, claiming that British courts did not have jurisdiction over Sealand as it was beyond the territorial waters of Britain. Bates used this as de facto recognition of his independent country.11 Bates declared himself Prince Roy of Sealand and bestowed the title of princess on his wife, Joan, and upon occupation, the Bates family furnished the fort to make it inhabitable: a dining room, kitchen, bedrooms, quarters for security staff, showers, a radio room, generator rooms, and a fuel store was added.

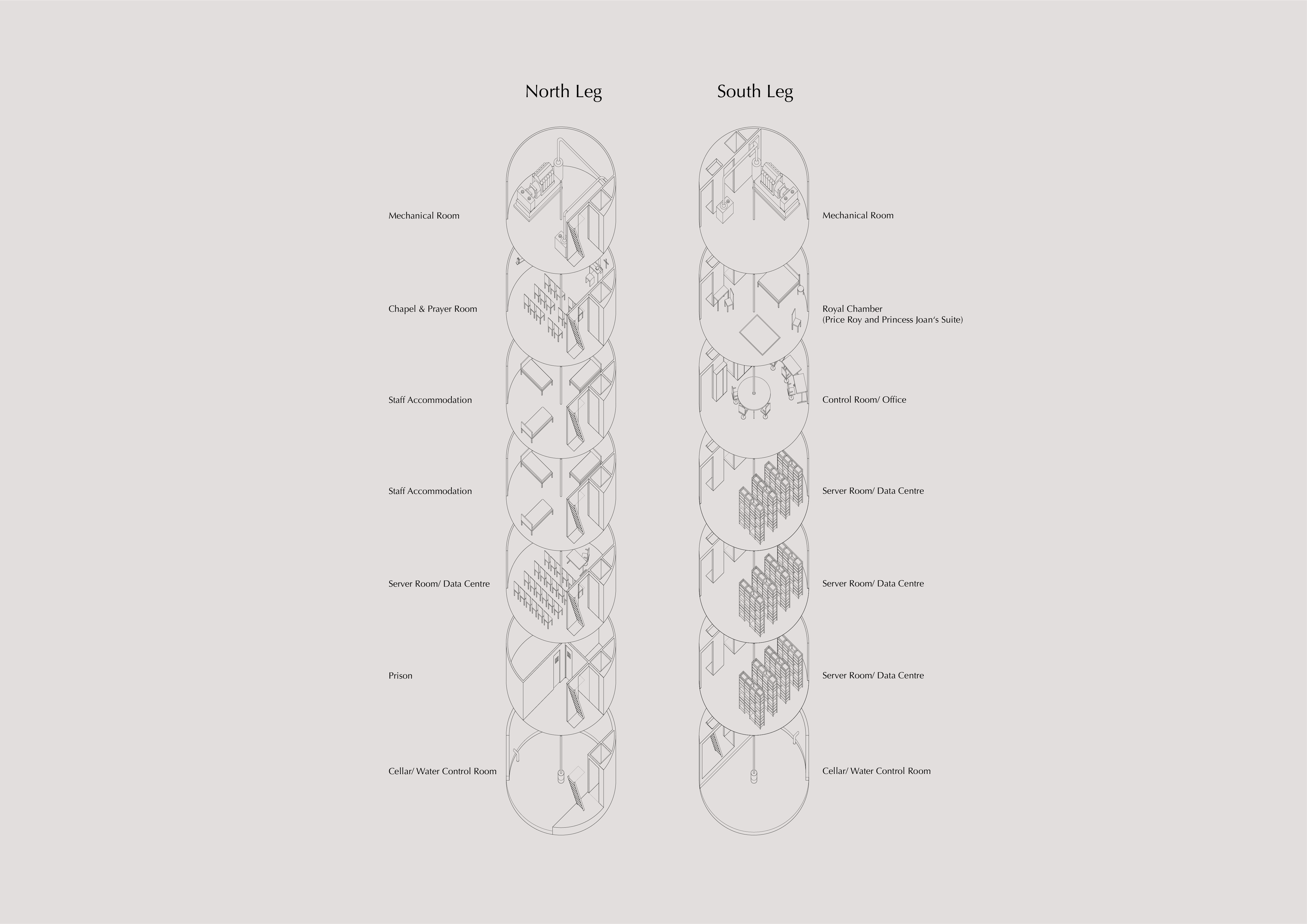

Despite the renovations, Sealand has maintained its unique architectural form. The platform is oriented north to south, sixty feet above the water. On the south end of the deck, a rusty 3.7-inch AA Gun, left from WWII, is still visible. Perhaps it was last used in 1978 when a group of German and Dutch men, led by Alexander Achenbach—a former German citizen and a diamond dealer—attempted to invade Sealand.12 Water and fuel tanks are lined up against the wall of the row (the roofed space between the cabins). Right above them is the unmistakable Sealand logo, painted with large white lettering. A crane, flagpole, radio antenna, and satellite dish stand out among other noticeable objects on the deck. Upon occupation, the octagonal control tower and radar house were removed and replaced by a helipad. Right below the helipad, the roofed space on the main deck level is cut through by a meter-wide corridor; washrooms, bathrooms, and toilets for the crewmembers and the staff arranged on one side; on the opposite side is the kitchen (galley), office spaces, lounge and gathering rooms, and transmitter room. All the rooms are lit by natural light with windows providing fresh air.

The two huge hallow legs house an engineering workshop, accommodation rooms, and fuel stores. A five-level computer center has been located in the south leg since 2000. Each cylindrical tower is divided into seven floors and are connected vertically by ladders and a lift. Under the main deck are generators and electrical facilities; they are easily accessible with the ventilation required to meet safety measures. However, on June 23, 2006, the top platform caught fire due to an electrical fire in the mechanical rooms. Most sections of the top floor were burned and badly damaged. The damaged spaces were later restored, and the roofed space was extended to the north side of the platform.

The north leg is dedicated to accommodations for the crewmembers and staff. On the second level, below deck, there is a chapel and praying room: a half-empty circular space with a cross hanging on the wall and a simple desk humbly below. There is a conference room for official meetings and gatherings on the fifth level. At one time the sixth floor was used to store arms and explosives. The one on the north is now a jail while the other is a server room. Their walls are thicker, and the space is divided into smaller parts in order to control possible explosions. Water pumps and safety valves mostly occupy the last floor. The second floor down on the south leg used to be the royal chamber, where prince and princess Bates were housed. Today the room is a UPS (uninterruptible power source) and computer server room, monitoring and controlling the databanks stored in the floors below. Below the server room is a communal workstation. After 2000, a multistory data center replaced the accommodation chambers after Sealand officials formed a partnership with the data haven start-up, HavenCo, to create an offshore data hosting company that would stand outside British restrictions on privacy, copyright, music sharing, and censorship. HavenCo refurbished part of the platform and built the data center.

It was in late 1999 when Sean Hastings and Ryan Lackey, two members of Cypherpunks, a crypto-anarchist group, and owners of HavenCo, started negotiating with Bates to transform the Sealand platform into a fat-pipe internet server and global networking hub.13 It was intended to be the world’s first truly offshore, almost-anything-goes electronic data haven—a place that occupies a tantalizing gray zone between what is legal and what is possible.14 Both Hastings and Lackey were thoroughly committed to the cypherpunk vision, and their creation HavenCo should be seen in light of their manifesto, released in August 1988:

Computer technology is on the verge of providing the ability for individuals and groups to communicate and interact with each other in a totally anonymous manner. […] These developments will alter completely the nature of government regulation, the ability to tax and control economic interactions, the ability to keep information secret, and will even alter the nature of trust and reputation. […]

The State will of course try to slow or halt the spread of this technology, citing national security concerns, use of the technology by drug dealers and tax evaders, and fears of societal disintegration. Many of these concerns will be valid; crypto anarchy will allow national secrets to be trade freely and will allow illicit and stolen materials to be traded. An anonymous computerized market will even make possible abhorrent markets for assassinations and extortion. […]

Just as the technology of printing altered and reduced the power of medieval guilds and the social power structure, so too will cryptologic methods fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions. Combined with emerging information markets, crypto anarchy will create a liquid market for any and all material, which can be put into words and pictures. And just as a seemingly minor invention like barbed wire made possible the fencing-off of vast ranches and farms, thus altering forever the concepts of land and property rights in the frontier West, so too will the seemingly minor discovery out of an arcane branch of mathematics come to be the wire clippers which dismantle the barbed wire around intellectual property.

Arise, you have nothing to lose but your barbed wire fences!15

The Bateses were immediately interested—it was the first proposal “that seemed to be really suited to what we are,” Roy would later say.16 A deal was struck a year later; HavenCo received an exclusive lease on part of the territory of Sealand for its data-center operations. HavenCo subsequently refurbished part of the south leg as a multilevel office complex. By the end of 2000, HavenCo had hired its key employees, studied the relevant international law, and raised the money needed to get going. Along with Lackey, major personnel included Sean Hastings and his wife, Jo, who were experienced in programming, offshore financing, and online gambling. HavenCo’s chair, Sameer Parekh, was a computer security specialist who launched the crypto software company C2Net. Parekh confidently predicted HavenCo would return $50 million to $100 million in profits by the end of its third year in business.

The ultimate success of HavenCo was highly dependent on the quality of their cyber infrastructure. Although in the first years they managed to get high-speed data access, namely a satellite link, a pair of 155-Mbps microwave links operated by Winstar Communications, and a ring of high-speed fiber-optic cables installed by Flute, a UK-based corporation that builds undersea optical cable and sells access to its customers. HavenCo was not only running under Sealand’s juridical title, but it was also nationalized by Michael Bates since the its staff and servers were physically located there. But things did not go as planned; the fiber-optic cable wasn’t ready on time, Flute went bankrupt, the microwave links were oversold to multiple users, and the satellite link had a limited bandwidth. Consequently, HavenCo gradually lost its clients due to poor service and lack of investment. The company’s website went offline in 2008.

Despite HavenCo’s dramatic ending, the ship kept sailing. “Listen, old boy,” Bates told a journalist right before buying HavenCo in 2000, “I like a bit of adventure. It’s the old British tradition. Maybe Britain’s changed, but there’s a lot of us still about.”17

In 2007 Pirate Bay, a Swedish website that hosts BitTorrent tracker files and claims to be the world’s largest, announced its plans to buy Sealand.18 Following its temporary closure after a raid by Swedish police in 2006, Pirate Bay had a short stay in the Netherlands and returned to a new Swedish server. In order to prevent another attack, the group set up a campaign to raise money to buy Sealand. They believed that being located outside the jurisdiction of any nation-state would let the cyber platform run safely. However, the Spanish real estate agent acting for the self-proclaimed nation also declared that Pirate Bay may not be allowed to buy it because it pledged not to allow a sale that would damage the interests of or act against the United Kingdom.19 Controversially, in December 2010 the Sealand government announced that it had been asked to give Wikileaks founder Julian Assange a passport and a safe haven. Michael Bates admitted, “There has been contact but we cannot really talk about it […] Any such dealings would be a private business arrangement and all our dealings with our clients are confidential.”20 There has been no further news about how the negotiations since January 2012.

Pirates, DJs, and hackers represent a form of labor, which has the potential to reinterpret the spatio-temporal structure of global economic systems. Through the momentary suspension, provided by the state of exception, these forms of life could create a possibility of what Paolo Virno would call, “innovative action.”21 Shrouded in the ambiguous spatial and juridical conditions of Sealand, the collective form of contingent labor could escape the gaze of corporate state markets, taking on the free territory of the sea, cyberspace, and intellectual capital. Sealand resembles a form of sanctuary for almost any innovative collective action. Its brutal military architecture has not been a space of confrontation but rather a space of fulfillment where the spaces of living, production, and distribution merged, and fluxes of goods, capital, and information mobilized. Paradoxically, such rigid spatial appropriation could potentially expand and transform the “free sea” law into a new land order.

In his account, Schmitt employs the term nomos to explain multifaceted yet controversial aspects of spatio-temporal application of law. The Greek word nomos connotes “a wall around the Greek house, division, distribution, and appropriation.” It also stands for “concrete order”—or the concept of law—that is traditionally bound to spatial organization and land appropriation. Schmitt suggests revisiting the idea of nomos in order to explain the changing relation between the firm land and the free sea. By going beyond such binary division, nomos offers a third spatial condition wherein free movements are first captured and organized and then distributed. The order of space becomes a fundamental device through which alternative power relations are achieved.

-

Carl Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of Jus Publicum Europaeum (New York: Telos Press, 2006), 43. ↩

-

See Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Giráldez, “Globalization Began in 1571,” in Globalization and Global History, eds. Barry K. Gills and William R. Thompson (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 232–247; or Martin Thomas and Andrew Thompson, “Empire and Globalisation: From ‘High Imperialism’ to Decolonisation,” the International History Review, vol. 36, no. 1 (2014): 142–170. ↩

-

The book A General History of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson (1724) notes many examples of pirates and privateers who used a false flag, such as John Martel and Bartholomew Roberts. Next to them there were figures like Jean Lafitte (1780–1823)—a French privateer and a pirate—who operated in the Gulf of Mexico, with letter of marque from a nonexistent country, which authorized shops sailing from Campeche as privateers to attack vessels from all nations. See Myra Hargrave McIlvain, Texas Tales: Stories that Shaped a Landscape and a People (Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2017). ↩

-

In 1608 the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius published the first comprehensive account on the international law and the rights of the sea, De Jure Praedae. He was asked by the Dutch East India company to produce a work against the idea of the monopoly of trade on the sea, which had been claimed by the United Kingdom of Spain and Portugal in the early seventeenth century. In De Jure Praedae, Grotius argued that the sea belongs to all men, under the famous title Mare Liberum (“The Freedom of the Seas”). However, the principle of Mare Liberum was widely circulated and often reinterpreted by the sea powers to disguise economic reasons and colonial expansions. ↩

-

Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth, 311. ↩

-

Historically, the foundation of law has been based on the founding act of land appropriation and territorial definition. The controversy here was that Sealand was a man-made artificial platform. But since the structure was submerged by the sea, it was regarded as part of a larger landmass. Hence the statehood could have been claimed. ↩

-

See James Grimmelmann, “Sealand, HavenCo, and the Rule of Law,” University of Illinois Law Review, vol. 2 (2012), 405–484, link. ↩

-

See Adrian Jones, Death of a Pirate: British Radio and the Making of the Information Age (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), 28–36. ↩

-

Daily Telegraph Reporter, “Appeal by Radio Essex Dismissed,” Daily Telegraph, January 18, 1967. ↩

-

Radio 355 was a pirate radio and successor to Britain Radio in early 1967. It was located on the ship Laissez Faire navigating in the North Sea, off the coast of Essex. Despite the radio station’s initial difficulties and its relatively short life span, estimates in mid-1967 showed that Radio 355 had built an audience in the region of 2.25 million. ↩

-

John Ryan, George Dunford, and Simon Sellars, Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations (London and Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet, 2006). ↩

-

See Grimmelmann, “Sealand, HavenCo, and the Rule of Law,” 426–428. ↩

-

Steven Levy, Crypto: How the Code Rebels Beat the Government—Saving Privacy in the Digital Age (New York: Penguin, 2001). ↩

-

Simson Garfinkel, “Welcome to Sealand. Now Bugger Off,” Wired, January 7, 2000, link. ↩

-

John Markoff, “Rebel Outpost on the Fringes of Cyberspace,” New York Times, June 4, 2000. ↩

-

“Prince Roy of Sealand,” the Telegraph, October 11, 2012, link. ↩

-

Flora Graham, “How the Pirate Bay Sailed into Infamy,” BBC News, February 16, 2009, link. ↩

-

“Piratebay’s Sovereign Ambitions Blasted,” Out-Law.com, January 17, 2007, link. ↩

-

“Sealand/Felixstowe: Could Sealand Be a Safe Haven for Assange’s WikiLeaks?” Ipswich Star, October 4, 2012, link. ↩

-

Paolo Virno, “Jokes and Innovative Action: For a Logic of Change,” Artforum International, vol. 46, no. 5 (2008): 251–257. ↩

Hamed Khosravi is an architect, researcher, and educator. He received his PhD in The City as a Project program at TU Delft/Berlage Institute. Currently he is a lecturer in architecture and urbanism at the TU Delft Faculty of Architecture. His latest publication is Tehran—Life Within Walls (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2017). This essay is part of the research project, “The Nomos of the Sea: North Sea and the Architecture of Contingent Labor,” supported by Stimuleringsfonds NL.