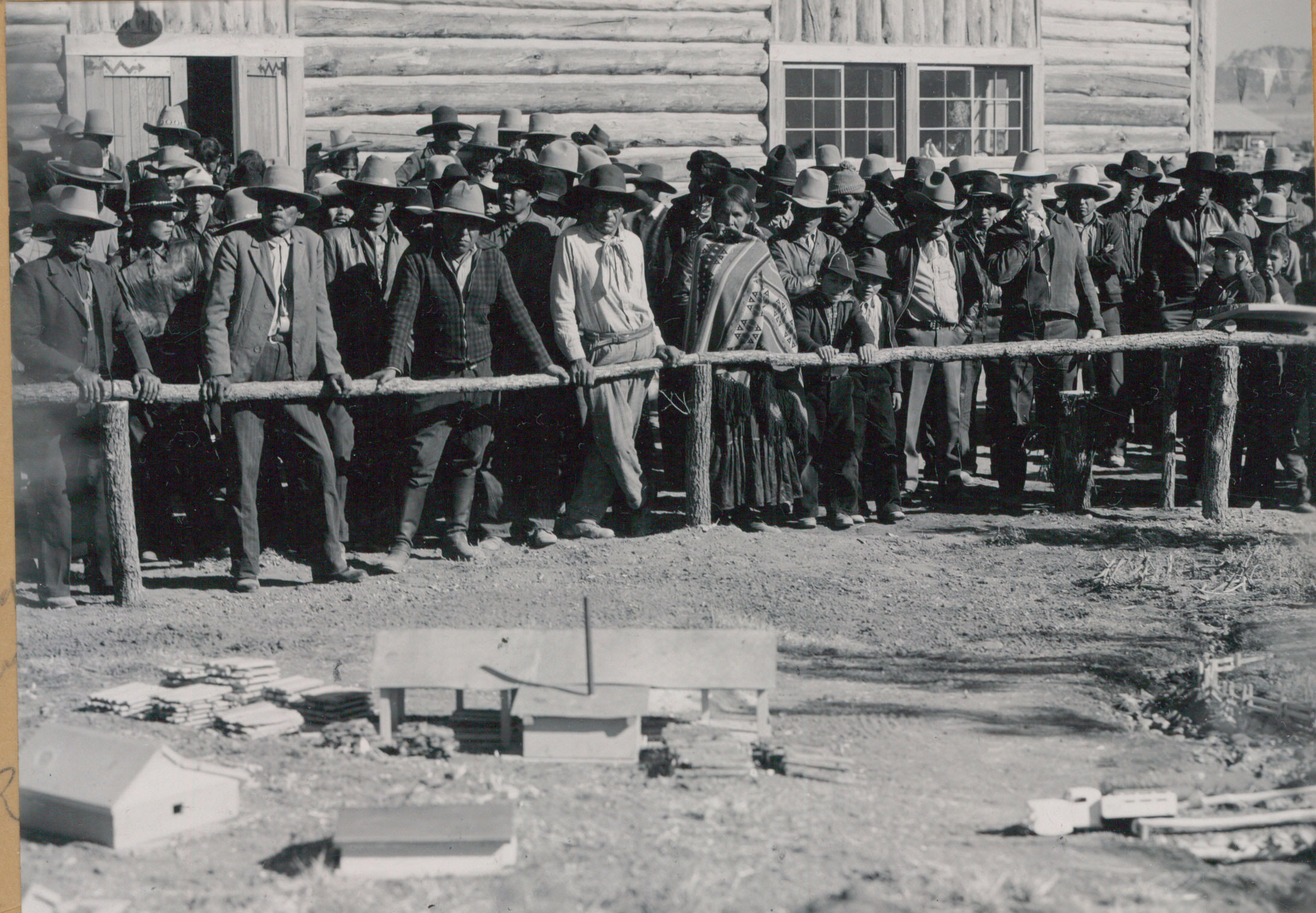

A singular photo, dated October 1939, characterizes the Office of Indian Affairs’ conflation of federal patronage with universal land heritage as the agency experimented in developing Native land, and also Native people. A crowd of Navajo men, and a single woman, dressed in non-traditional clothing stand behind a wooden fence. They are not dressed for hard labor or cultural ceremony. They have come to Window Rock, Arizona for the Tribal Fair, a social event involving livestock competitions, an open market, and exhibitions. There is something unique in how the photo is framed. In the background stand the Navajo people; immediately in the foreground is a miniature lumber mill complete with truck, home, and tiny ravine. Here the small-scale model acts as an object for demonstration—a federal experiment in disguising settler colonialism as a new vision of “modernity” that would increase Navajo autonomy.1

The 1930s marked an economic decline in the United States and, for Native people, indicated a new regime of tribal-federal relations. The newly appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier stressed that “in the long run, the Indians must be their own savers and their own helpers” and in doing so “every branch of the Indian service should be controlled by this principle.”2 Collier promoted “decreasing the paternalism of the government and extending civil rights and the facilities of modern business enterprise to the Indians.” Paradoxically, he still strongly believed that the responsibility of the United States was to continue acting as guardian of the Indians.3 His efforts resulted in the Indian New Deal: federal monetary aid set aside for tribal development.4

The Indian New Deal brought a suite of architectural interventions to the Navajo reservation and the surrounding region. This included the object of the Navajo men and woman’s gaze at the Tribal Fair: the demonstration station. From the photograph, the demonstration station is physically nothing more than a farm, a lumber yard, a ranch. However, when considered as a typology, the demonstration station becomes a proving ground for persuading Native people to heed the ideology of New Deal-era land conservation.5 These stations were proposed as a network of hubs for Native development. From this viewpoint, events on the Navajo reservation during the New Deal era can be read not as a bureaucratic history of Native-federal relations but rather as a trace of the Office of Indian Affairs’ disordered translation of a “modern” Native heritage: the idea that Native land is an object from the past whose conservation in the present can only be achieved through technocratic forms of conservation under the control of the federal government, framing traditional agricultural practices as a threat to regional sustainability.

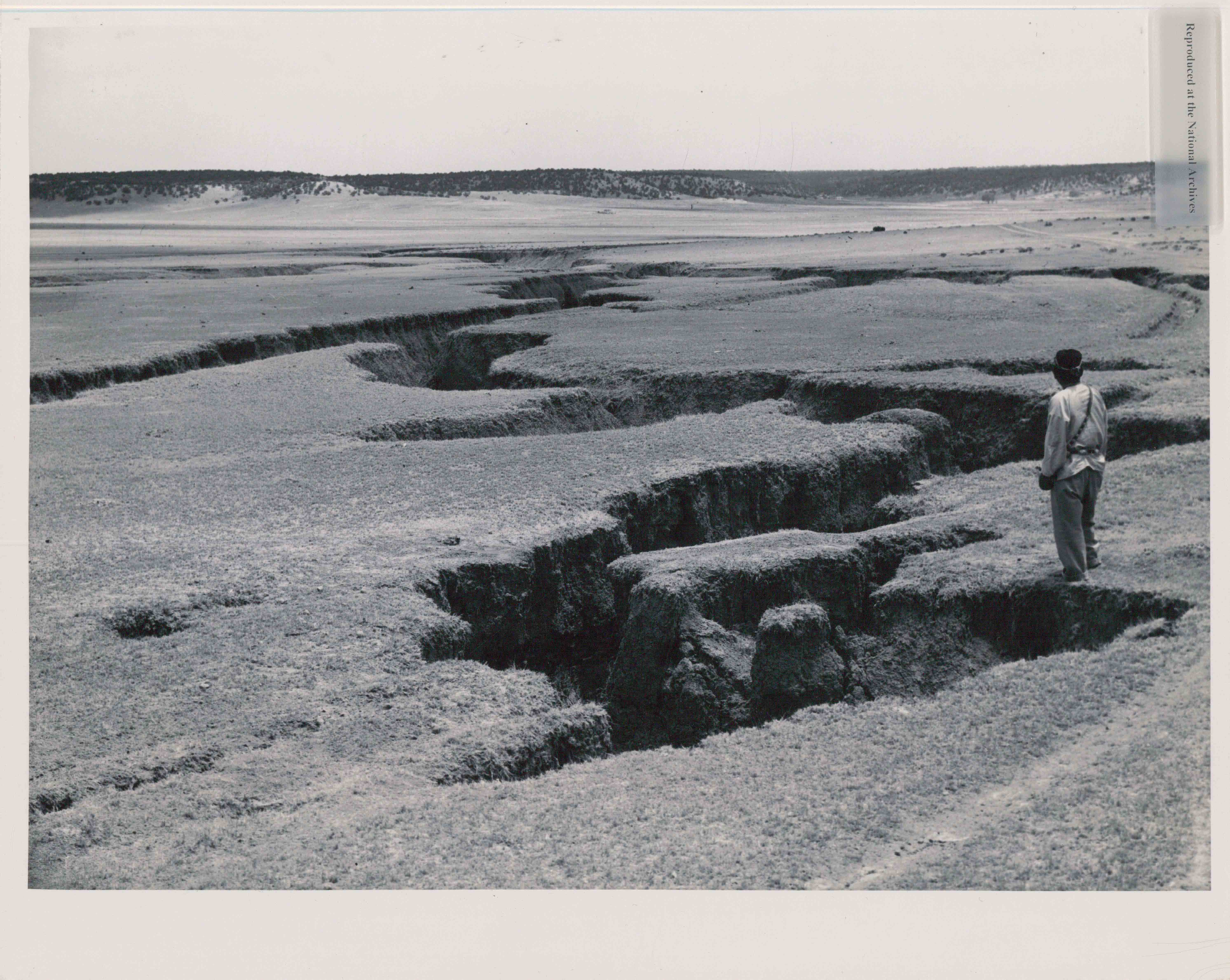

In the 1930s, federal officials invented a narrative of the decline of Native land. Historical land surveys informed individuals like Collier and Hugh Hammond Bennett, a soil scientist, of the “deep gullies” and “widespread erosion” depleting Navajo land.6 Later reports adopted the same urgency, proclaiming a decline in the quality of the range.7 While these reports were being written, construction on the Hoover Dam, then known as the Boulder Dam, began in order to sustain regional growth and urban development in places like California.8 At first the construction of the dam far to the west of the Navajo reservation may seem disconnected from Navajo land and people. However, the dam, the land reports, and the timing of the Indian New Deal presented an opportunity for outside “experts” to develop their policies aided by a vision of Navajo “modernity”—a reality situated in an administrative reordering and development of land first and Native people second.

Bennett, chairman of the Soil Conservation Advisory Committee, read and reread early historical surveys and saw the land firsthand before speaking to the Navajo Tribal Council on June 7, 1933. He connected the early reports of a declining range with its deep gullies as problematic for both the Boulder Dam and the Navajo people: “This land of the Navajos, which as with all people is the life-blood of those who live on it, is threatened. If something is not done to stop the losses, a great deal of suffering is in store for the people of the reservation, suffering that cannot be withstood.”9 Although Bennett cites the Navajo people as potential victims of degrading ranges, his primary concern centered on the decline of previously bounteous land.

Bennett told the council that if erosion continued unchecked, “ultimately the entire alluvial fill of most of the valleys of the Navajo reservation will be deposited behind the dam.” He made clear that this issue affected not only the Navajo people, but also “threaten[ed] the enormous Federal, State, municipal and private investments involved in, or directly or indirectly dependent on the maintenance of the storage capacity of the reservoir.”10 Regional planners feared a compromised reservoir would not only decrease the availability of electricity, but also hinder further growth in coastal cities like Los Angeles. Thus making the erosion of Native land, not only an immediate Tribal problem, but also a regional one.11 In response to this threat, Bennett proposed to the Tribal Council a regional plan for controlling the “widespread wastage now stealing the substance of the land.”12 The crisis was cast as the “Colorado Silt Problem” and positioned the Navajo reservation as “public enemy no. 1.”13 Bennett proposed minimizing the erosion of the range firstly by restricting animal husbandry on the Navajo reservation and secondly by launching a built solution—a building typology later labeled by Bennett and Collier as a “demonstration station.” 14

Throughout the Tribal Council meeting on June 7, 1933, the demonstration station was not spoken of in terms of benefiting the Navajo rancher; rather it was framed as an intervention for the sake of the land. Later Bennett and his team chose Mexican Springs, a watershed located between a high mountain plateau and low plains land, as the testing ground for the new typology.15 For Collier, the decline of land and the demonstration station provided an opportunity to promote a different narrative. Whereas Bennett sought to use the demonstration station as a tool for restoring the land to an ideal state, Collier viewed the program of the demonstration station as a site of modernizing collective Native identity, stating:

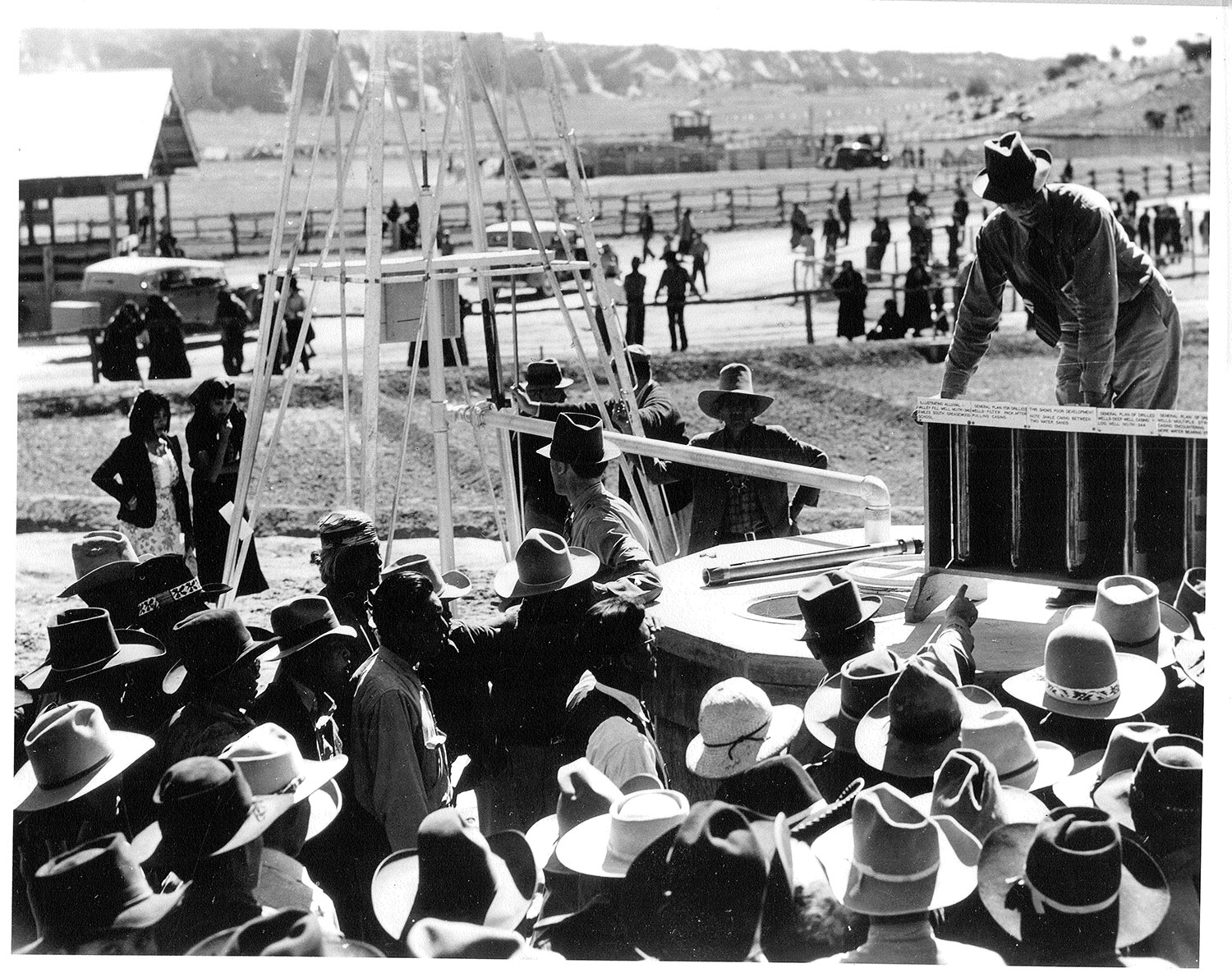

The Navajo project was organized under the direction of Hugh G. Calkins. A strong advocate of designing land-use programs along major watersheds, Calkins viewed the demonstration stations as an opportunity to practice his land management theories and to bring an influx of young non-Native technicians and soil experts to evaluate and record the land. In the spring of 1934, the group of technicians assembled on the reservation. Though the work of the demonstration station was created for the Native individual, the Navajos could not do it alone.

In the editorial “The Mexican Springs Erosion Control Station: An Institution of Education and Research,” Richard Boke writes of the training of a group of five hundred Navajos, “many of whom are prepared to take over that responsibility and leadership which will make the erosion control program a Navajo project-run apart from basic research tasks, by Navajos.”16 Boke’s assessment of the Navajo’s role within the demonstration station conveys a desire to position the 20 by 5 mile wide Mexican Springs demonstration station as an opportunity to study the land and improve the status of local Native residents.

The purpose of the demonstration area was to “demonstrate that the range may be brought back by reducing the animals to the carrying capacity, by instituting proper measures of erosion control and by providing necessary and possible water facilities for the animals.”17 A majority of the demonstration areas focused on livestock husbandry and range restoration. In this manner, the transfer of new knowledge aimed to encourage a new format of economic development on the reservation, one where Native people were the main protagonists of their own progress.

In 1934 Robert Fechner, director of Emergency Conservation Work, visited the American Southwest. He asked the Forest and Park Services to arrange a visit to see first-hand emergency conservation work in action on Native American reservations. Fechner visited the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and Blackfeet reservations, spending some time at Mexican Springs.18 In his editorial for Indians at Work, Fechner fed into Collier’s vision of productive Navajo people. He wrote:

I could not help but think how widely at variance the actual facts were from the prevailing white impressions. That is to say, everywhere I went I saw Indians working hard and displaying an intelligent interest in what they were doing, yet for the most part white people, ignorant of the Indians except hearsay, believe that they were averse to work and incapable of displaying the same kind of interest in a job that a white man would.19

Fechner’s remark on the work ethic of Native Americans and his surprise in finding that “prevailing white impressions” were in fact void reflect one peculiar thing about the arrival of the Indian New Deal on the Navajo reservation. In order for the Office of Indian Affairs to “prove” that it was not the totalitarian colonizer of previous administrations, it sought to express a keen “awareness” of Native heritage.20 Collier and Bennett pitched the typology of the demonstration station as a testing ground, meaning that both individuals sought to demonstrate “progressive” ideals and the formulation of a new methodology for the management of Native lands and Native people. Really though it was an extension of Donald Lee Parman’s analysis of the Indian New Deal overall, a “giant pilot project where ideas could be tested before being tried on other tribes.”21

As events of the Navajo New Deal took place, idealist bureaucrats, political agents, architects, and scientists from the Office of Indian Affairs to the Soil Conservation Service all engaged in the prospect of modernizing tribal nations. And as they did, they argued over how much agency and authority to give the Navajo individual. As much as they wished to position their proposals as granting Navajo people and land increased autonomy, they actually centered on a need to “modernize” the Navajo people according to federal ideals and development goals. The end result concluded with an inadequate experiment in Navajo nationalism still beholden to federal paternalism.

The solution arrived at by men like Collier and Bennett relied on continually performing the modern gesture of designating what is traditional by drawing a line between the progressive and the archaic and constantly moving that line. Within this act of architectural transformation, the station typology took on the dual role of signaling progress through novelty and control of the built environment, and of manifesting settler logics of preservation and development. Such an internal tension attests to the dual nature of modernity: the achievement of progress through newness and ordered change precariously balanced with an appeal to the authority of restoring the “old,” the “dwindling,” and the “failing” to a supposedly “whole” condition.

-

Settler colonialism is a relationship characterized by the state’s domination of land and by depriving Native people of their land and self-determination. This type of politics positions access to territory, rather than racial designation, as its principle mode of operation. See Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocidal Research, vol. 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–388. ↩

-

John Collier, “Statement for Release upon the Confirmation by the Senate and Nomination of John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs,” Box 83, Association on American Indian Affairs, Mudd Archive, Princeton University Library. ↩

-

Collier, “Statement for Release upon the Confirmation by the Senate and Nomination of John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs.” ↩

-

What is meant by development and how does it come to be deployed in relation to events taking place on the Navajo reservation during the New Deal? In framing this word and concept, see James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998); particularly his use of “High Modernism” in chapters three and four. ↩

-

For a timeline and overview of New Deal-era land conservation, see Donald Lee Parman, The Navajos and the New Deal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976). ↩

-

Navajo Agency, The Navajo Yearbook of Planning in Action (Window Rock, AZ: Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1955–1956). ↩

-

Navajo Agency, The Navajo Yearbook of Planning in Action. ↩

-

See the Soil Conservation Service and Navajo Soil, “Problems of Soil Erosion on the Navajo Indian Reservation and Methods Being Used for Its Solution, 1936,” as quoted in Richard White, Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988). ↩

-

Hugh Hammond Bennett, “Statement Presented to Navajo Tribal Council Meeting,” June 7, 1933, Fort Wingate, Arizona, Navajo Tribal Council Records. ↩

-

Bennett, “Statement Presented to Navajo Tribal Council Meeting.” ↩

-

Marsha Weisiger, Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), 82. ↩

-

Bennett, “Statement Presented to Navajo Tribal Council Meeting.” ↩

-

Navajo, Annual Report of the Navajo District (1937), 51–52. Available in the National Archives, RG 75, BIA, CCF 52368-1937-021. ↩

-

Many scholars have written on the practices and limitations of livestock reduction; see Weisiger, Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country; and Peter Iverson, The Navajo Nation, Contributions in Ethnic Studies, no. 3 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981.) ↩

-

Survey of Conditions of the Indians of the United States, Hearing before US Senate, Committee on Indian Affairs, part 34, “Navajo Boundary and Pueblos in New Mexico,” 75th Congress, 1st Session (1937), 17576–17577.

While in camp, the Indians would be employed in connection with carrying out the conservation program. Also, they would be subjected to an intensive educational campaign along lines of conservation and land use previously outlined, in the hope that at the end of their work period they would return to their homes as range-conservation missionaries and persuade their community or chapter to take over erosion and range control as a purely Indian function.[^16]

-

Richard Boke, “The Mexican Springs Erosion Control Station: An Institution of Education and Research,” Indians at Work, vol. 4, no. 2 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1934), 13–. Available in the Indigenous Peoples: North America Archive, Princeton University Library. ↩

-

Thomas Jesse Jones, Navajo Indian Problem: An Inquiry Sponsored by the Phelps-Stokes Fund (New York: Phelps-Stokes Fund, 1939), 32, link. ↩

-

Robert Fechner, “My Impression of IECW,” Indians at Work, vol. 4, no. 2 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1934), 15–. Available in the Indigenous Peoples: North America Archive, Princeton University Library. ↩

-

Fechner, “My Impression of IECW.” ↩

-

In this analysis heritage not only denotes cultural significance granted to objects and rituals but also relates to the production of what Paul Betts and Corey Ross call “heritage industries,” in which heritage is linked to empire building, international development, and the invention of tradition. See Paul Betts and Corey Ross, Heritage in the Modern World: Historical Preservation in Global Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). ↩

-

Parman, The Navajos and the New Deal, 24. ↩

Zoë Toledo is a Diné researcher, designer, and writer. She studied architecture at Princeton University and will be attending Harvard’s GSD for her masters of architecture this upcoming fall.