The Arabic language has no direct equivalent to arabesque, a term that Europeans invented about five hundred years ago to describe works “in the Arab style,” many of which were made by Westerners dabbling in exoticism. Artist Rayyane Tabet highlights this linguistic asymmetry—and the historical-political asymmetries that it reflects—in his solo exhibition, Arabesque, which runs until April 18, 2020, at Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York. The gallery’s opaque gray façade displays a ninety-three-foot-long vinyl supergraphic of the Arabic transliteration of arabesque ( أرابيسك ), which, for those of us not literate in Arabic, becomes a kind of decorative abstraction. It’s meta-arabesque. Even people who read Arabic may find the stylized lettering enigmatic. The root word Arab and the transliterated suffix -esque are pulled to opposite ends of the façade, joined by a long horizontal line that becomes an ambiguous figure of its own: a metaphor for the vast distances that Tabet’s work travels between languages, cultures, and epochs. This spectacle of improvised translation is a clever way of showing how artificial, and central, the concept of arabesque has always been in Euro-American theories and practices of ornament. There is no timeless “Arab style” outside the Western imagination.

Architecture frequently appears in Rayyane Tabet’s work; he earned a bachelor of architecture degree from the Cooper Union before focusing on art. But his most vital medium is storytelling. Tabet, who was born in Lebanon and is based in Beirut, pieces together stories in which architecture and architectural fragments illuminate sociopolitical events and individual lives. He relishes paradox, finds hidden connections, and gravitates to the gray zone between documentation and creation. He builds stories out of history and hunch. At once systemic and idiosyncratic, Tabet’s storytelling method drives his work at Storefront and his concurrent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alien Property (through January 18, 2021).

At Storefront, the Arabesque calligraphy is one of three works in the exhibition. The second is Collages, a series of wall-mounted compositions that reinterpret nineteenth-century drawings of Egyptian ornament by the French architect and ornamental specialist Jules Bourgoin. The third work, Assemblage, consists of a stack of redwood corbels salvaged from an Arts and Crafts church in Berkeley, California, designed by the American architect Julia Morgan, plus documents pinned to a bulletin board. Each of the three works is accompanied by a short story written by the artist.1

These texts, though understated in writing style, zig surprisingly across time and space, weaving together moments of art history, personal history, and social history. For example, Tabet’s 232-word statement on his Collages begins, “In 1892, Jules Bourgoin… published Précis de l’Art Arabe (“A Summary of Arab Art”), a series of 300 drawings…” then goes on to say that in 2016, “I found at Arc en Ciel, a second-hand store in Beirut, a copy of Bourgoin’s Précis,” and that this shop burned down in 2019 amid the wildfires that swept across Lebanon. The story concludes, “following the government’s ineffective response to the fires, decades of corruption, and recent tax increases, a revolution began in Lebanon.” There’s no causal relationship between the old treatise and the protests that recently brought down the Lebanese government, but Tabet exploits a thin narrative thread—as tenuous as the long stroke that joins Arab and -esque on the gallery façade—as a creative opportunity.

Inside Storefront’s wedge-shaped gallery space, the printed plates of Bourgoin’s Précis are displayed in four rows that extend right to left, like Arabic writing. The drawings represent the architecture, carpentry, and ornamentation that Bourgoin surveyed while taking part in a decades-long French archaeological mission to Egypt.2 The book is a telling example of Orientalist scholarship: at once valuable as a documentary resource and tainted by the exploitative framework of European archaeological missions of the era. Many of the drawings are excellent. But Tabet is not simply resurrecting or paying homage to the work of a forgotten theorist of ornament.

He has dissected and recomposed Bourgoin’s plates in a manner that results in the destruction of the original work. The pages are neatly removed from the binding and mounted in tight rows on the wall—but with the verso facing out. Demonstrating the same zealous attention to detail and disregard for the integrity of context that Orientalist collectors once demonstrated for the arts of the Middle East and North Africa, Tabet has carefully sliced around the edges of each of Bourgoin’s illustrated figures, leaving one edge as a hinge, then folded them back so that the drawings pop out in low relief against the yellowing, spotted paper. Each cutout figure leaves behind a sharply delineated void as it folds right, left, up, or down, sometimes overlapping other figures and voids. Intentionally or not, these sliced-and-folded sheets echo the swiveling panels of Storefront’s puzzle-like façade.

The Bourgoin drawings thus become raw materials for recomposition. But what becomes of these newly liberated spolia after Tabet has pried them from the grip of Eurocentric historians? Tabet does not attempt to restore the reclaimed ornamental fragments to their historically correct context but further abstracts them. The curatorial description of Collages reads, “In recombining drawings originally intended to be an analytical survey of ‘Arab art,’ the work creates composites that, while following the original taxonomic logic devised by Bourgoin, open up the possibility that ornamentation is not a stylistic form to be replicated but rather a system to be freely appropriated, reworked, and reinvented.” The use of the word system is significant here since Tabet opted to modify Bourgoin’s entire set of drawings according to a set of rules or criteria that he devised. As Antoine Picon observes with respect to ornament, “Rules are essential to allow architecture to connect to its own history in a productive way. The constant negotiation between tradition and novelty presents a political dimension, a juggling between resistance and acceptance.”3 At the same time, Collages reflects the serendipity of the artist’s discovery of the Précis. Also notable is the phrase “freely appropriated, reworked, and reinvented,” implying a nonhierarchical flow of ideas and property across cultures, in contrast to the Western-dominated flow of knowledge and art in Bourgoin’s day. How this might translate into contemporary architectural design remains for the visitor to imagine.

Bourgoin’s brief preface and captions that originally accompanied the plates of his Précis are not included in Tabet’s exhibition, but Bourgoin began the work with a nostalgic tribute to Old Cairo: “Our descendants will no longer know the enchanting memories [Cairo] left to those who could see and love it before modern progress had developed its work of rapid transformation and unnecessary vandalism.”4 In lamenting the march of modernity, Bourgoin confirmed the essentialist bias that he and his contemporaries brought to their study of the region. It was in the late nineteenth century that Western European theorists invented the blanket category of “Islamic art and architecture,” collapsing centuries of change and countless regional variants into a timeless, essential phenomenon characterized by a focus on surface decoration and “reductive taxonomies of the arabesque,” as historians Gulru Necipoglu and Alina Payne write in their introduction to Histories of Ornament.5 The flawed category of “Arab art” tended to flatten distinctions between works made in, say, Mamluk Egypt, Umayyad Iberia, Abbasid Iraq, Safavid Iran, Mughal India, Timurid Central Asia, or Ottoman Turkey or Lebanon.

In his 1879 work, Les éléments de l'art arabe (“Elements of Arab Art”), Bourgoin ventured to characterize “Arab Art” as having “Elegance and complexity through geometric involutions…constructed with symmetry. Abstract figures, linear bending and a kind of organic growth.”6 This sounds innocuous enough, but it devolves into racist speculation: “From the fact that the inspiration of the Arab is dry and purely abstract, it follows that his intellectual or artistic development has remained little varied and has not opened up to new horizons.”7 This reductive, ahistorical view was coupled with a vision of global domination. “It will be too late to study humanity when there is no one left on Earth but Europeans” is the opening statement of Bourgoin’s 1873 book, Théorie de l'ornement (“Theory of Ornament”).8 Bourgoin serves handily as a target for criticism, but some of his peers were even more blinded by racism. Albert Jean Gayet, author of L’art Arabe (“Arab Art”) of 1893, wrote of the “artistic inaptitude of the Semite”9 and claimed to dislike the term “Arab art” not because it was too broad and ahistorical but because, he wrote, “The Arab has never been an artist.”10 He furthermore asserted that Arab culture, specifically that of nomadic peoples, existed outside of the forces of history: “The main traits of [the Nomad’s] character, manners, and way of life [in ancient times] did not in the least differ from his traits during the time of Muhammad or today.”11

Racist assertions such as these provided ideological cover for political and economic assault on entire regions and peoples. Pseudo-scientific analysis, including nineteenth-century art-historical treatises, helped sanction imperialist conquest and the extraction of physical and cultural resources. Jules Bourgoin may have genuinely admired the works he documented in his coolly rational anthologies of ornament from the Middle East and elsewhere, but the context in which he traveled and produced his studies was anything but neutral: Europeans, often competing with one another on a nationalistic or institutional basis, appropriated and expropriated many of the treasures they encountered. That is how so many remarkable works from around the world ended up in the encyclopedic museums of Europe and America, such as the Met.

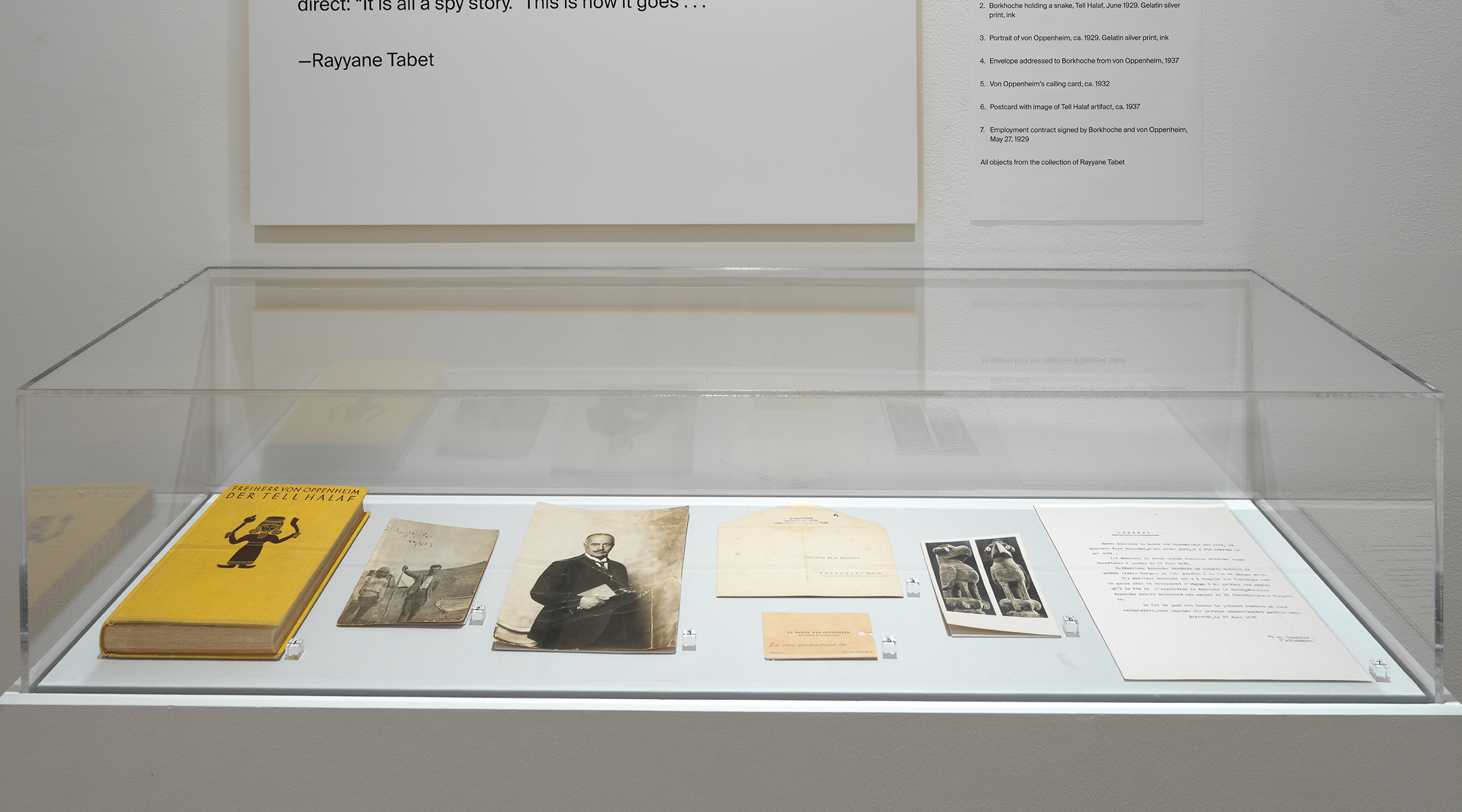

Tabet’s multipart intervention at the Met, Alien Property, is set in the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, in two rooms flanking the monumental Assyrian Royal Court on the second floor. Here, Tabet offers up an intriguing “spy story” involving his great-grandfather and a German archaeologist and a troubling, related story concerning the dispersal and loss of a series of ancient carved stone slabs. He bases these stories on a combination of objects and institutional documents in the Met’s collection and personal items and heirlooms from his family. In association with these stories, Tabet exhibits thirty-two charcoal rubbings—part of an ongoing series—that he has made of stone reliefs that survive in the collections of the Met as well as the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the Louvre Museum in Paris, and the Walters Museum in Baltimore.

As the story goes, in 1911, Baron Max von Oppenheim, a German diplomat and amateur archaeologist, discovered the remains of an ancient city in an excavation at Tell Halaf, in present-day Syria, which was then under Ottoman rule. Most dazzling was a sequence of 194 stone slabs, or orthostats, carved in low relief, which formed a narrative frieze along the base of a palace. The carved basalt and painted limestone panels, thought to be approximately three thousand years old, depict mythical creatures and scenes of hunting, war, ceremonies, and daily life.12 Unfortunately, these ancient architectural ornaments were dispersed, damaged, and destroyed after being unearthed. “Prior to their dispersal,” Tabet says in his written and audio-recorded story, “the reliefs were meant to be drawn, photographed, measured, and replicated in plaster. But due to the sudden outbreak of World War I, this work was left unfinished.”

During the First World War, the British Navy seized fourteen of the reliefs from a Berlin-bound ship and eventually deposited them in the British Museum. When Oppenheim returned to the site in 1927, he found that sixty-one reliefs had gone missing. The remaining reliefs were divided up, with Oppenheim hauling about eighty back to a museum he founded in Berlin, but at least twelve reliefs were irreparably destroyed in 1943 in the Allied bombing of Berlin.13 Dozens more were shattered into some twenty-seven thousand fragments that conservators would later attempt to reassemble at the Pergamon Museum. That same year, eight German-owned reliefs being stored in New York were seized by the US Office of Alien Property Custodian; four entered the collection of the Met. The National Museum of Aleppo received thirty-five reliefs in the late 1920s, one of which subsequently went to another museum in Syria; these may or may not have been evacuated before the national museum was damaged in 2016 amid the conflict there. Tabet’s charcoal rubbings of the surviving orthostats are installed in a way that echoes the original placement of the stones in-situ so that they can be imagined as part of an architectural ensemble rather than isolated works of sculpture.

The most surprising and compelling part of Tabet’s intervention is the way he embroiders art history with personal narrative. “Growing up, I ate lunch with my maternal grandparents every other Sunday,” Tabet begins. Obliged to sit politely for long hours, “I could see hanging on the wall a framed photograph of a man who did not look like anyone in my family. There was also a bright yellow book, written in German (a language no one in my family spoke), sitting on a shelf among a pile of books.” Years later, Tabet discovered that the photo was signed by a Baron Max von Oppenheim. When he opened the yellow book, he found a postcard from Oppenheim to Tabet’s great-grandfather, Faik Borkhoche, and a 1929 photo of Borkhoche standing under the scorching sun of Tell Halaf, wearing a sport coat and holding “the snake I caught hidden under a Bedouin’s tent,” as an accompanying letter explains. Tabet asked his mother, “How did memorabilia belonging to a member of the German nobility come to be in the dining room of a relatively quiet Lebanese family, and what was my great-grandfather’s connection to it?”

It turns out that Faik Borkhoche was assigned by French colonial authorities to serve as a secretary to Oppenheim during the final stages of the excavation at Tell Halaf—and also to spy on him. French officials suspected Oppenheim of gathering military intelligence under the cover of his archaeological obsession. Oppenheim and Borkhoche stayed in touch for years after the excavation was complete. Another twist: Oppenheim had first glimpsed buried treasure in 1899 while passing through on a railroad-building mission. According to Tabet’s tale, it was local Bedouin “tribesmen” who originally told Oppenheim about the ancient sculptures, “hoping that the curiosity of this foreigner would lead him to dig up” the stones, which they believed to be cursed. If this is true, Oppenheim played right into their script. And so, with a dazzling story and a few carefully chosen pieces of evidence, Tabet imbues ancient ornament with fresh meaning. In what first sounds like an Indiana Jones–style scenario of Western archaeologists racing to steal ancient treasure from Eastern lands, Tabet brings forth his great-grandfather from the shadows as an overlooked “agent” in the story. The exhibition of family heirlooms (“alien property” of another kind) also includes fragments of a sixty-five-foot-long goat-hair rug that Tabet’s great-grandfather received from Bedouin at Tell Halaf. Borkhoche directed his children to divide and subdivide the rug equally among their offspring “until the rug eventually disappears.” Looking at the ancient orthostats sitting in a corner of the same gallery, one senses that they may ultimately follow a similar course.

Tabet attempts a similar exercise in creative storytelling, but on a much more modest scale, with his Assemblage installation at Storefront. Here the physical remnants that serve as narrative scaffold are twenty weathered redwood corbels that were once part of St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Berkeley, California, built in 1910 to the design of architect Julia Morgan. Morgan was the first woman admitted to the architecture program of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the first woman to become a licensed architect in California. “Over the course of forty-two years of active practice,” Tabet writes, “she designed more than 700 built structures, holding the record for the most completed works by a single American architect.”

There is no indication that Morgan had direct contact with Jules Bourgoin at the École, but their commingling in the gallery makes it tempting to imagine. Although Morgan’s best-known work is the eclectic and ostentatious Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California, the rustic wood church in Berkeley reflected her preference for local materials and the Rationalist principles taught at the École.

The church has virtually no applied ornament of any kind. Responding to her client’s almost impossibly small budget, Morgan “produced a building that was entirely structure, save for exterior sheathing and fixtures,” as the historian Richard Longstreth wrote.14 Morgan designed the exposed studs and trusses to present a visual coherence.15 In 2017, Rayyane Tabet found and bought the lot of corbels, which once held up planters on the church façade, at a salvage shop in Berkeley for $600 plus tax (he displays the receipt to prove it, along with a few archival documents on the church’s construction and preservation). The corbels had apparently been replaced in the 1970s before the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and converted to a playhouse. “The carpenter in charge of the project had kept the corbels,” Tabet writes, “but decided to sell them to the salvage store when he ran out of space.”

While Rayyane Tabet’s storytelling method appears to be portable, his piece on the salvaged corbels is less compelling than its counterpart at the Met or the other components of his Arabesque. Maybe it’s just that Tabet had a much smaller budget and space to work with at Storefront. Maybe it’s that plain wood corbels can’t compete with three-thousand-year-old basalt slabs carved with images of winged lions. Maybe it’s the lack of the secret sauce, espionage. Or maybe Assemblage feels incomplete because it lacks a strong creative or transformative intervention comparable to his charcoal rubbings at the Met or his artful cutouts at Storefront. Stacking the corbels to form a minimalist tower is a logical enough idea for a small gallery, but it might be more interesting if the blocks were altered or reworked in some way.

Prefiguring Tabet’s decision to ship a set of salvaged corbels from Berkeley to New York and make an exhibition out of them, Julia Morgan once designed a “medieval museum,” never built, out of salvaged building components. In 1931, William Randolph Hearst purchased a twelfth-century monastery from Spain and had its stones packed and shipped to San Francisco. He wanted to resurrect it as the centerpiece of a museum in Golden Gate Park; Morgan prepared the design. Short of money during the Depression, Hearst donated the building blocks to the city of San Francisco in 1941. But the crates, left unprotected in the park, were destroyed by fire.16 Some of the remaining stones are now scattered throughout the park. This story is not part of the exhibition, but it fits nicely with Tabet’s treatment of ornament.

So, too, does the story of Hearst bringing a secondhand book to Morgan’s San Francisco office in 1919, for their first meeting about his 270,000-acre estate at San Simeon. According to Morgan’s associate Walter Steilberg, Hearst arrived with a “bungalow book” that he claimed to have found while “prowling around second-hand book stores” in Los Angeles.17 He singled out one picture with the idea of “keeping it simple—sort of a Jappo-Swiss bungalow.” As the project morphed into something completely different—at once a residential compound, a museum for Hearst’s art and antiquities, a command center for Hearst’s business empire, and a celebrity playground—Morgan took on the complex task of incorporating elaborate architectural elements from her client’s collection: decorated ceilings from Spanish castles, choir stalls from churches, intricate Venetian windows, and sculptures from around the world. The 144-room complex contains salvaged and simulated Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque spaces. Morgan was far more scrupulous and restrained than Hearst in her use of historical sources, but she had no qualms about employing and reinterpreting past architectural styles.18 Only a few explicitly “arabesque” embellishments can be discerned at Hearst Castle, but its vaguely “Southern Spanish Renaissance” style19 is nonetheless suffused with the Islamic design influences that thrived in Andalusia and beyond even after the Reconquista.

What condition the St. John’s corbels will be in a century from now is anyone’s guess. But given that many of the ancient reliefs excavated at Tell Halaf in the early twentieth century did not survive more than a few decades of global circulation, perhaps the likeliest fate of any displaced architectural material is oblivion. Only the lucky few survive the risks of decay, neglect, war, fire, water, obsolescence, bankruptcy, or simply falling out of fashion. Even museums are bombed sometimes. Private collections are fleeting. William Randolph Hearst, according to some accounts, could not keep track of all the precious antiquities he owned.20 Architects can’t guarantee the preservation of their drawings or buildings. Julia Morgan didn’t even try. As Rayyane Tabet writes in the closing words of his story on the corbels, “In 1951, shortly after closing her office, Julia Morgan burned all of her files and blueprints as well as most of her office records on the grounds that her clients had their own copies and that no one else would ever be interested.”

But Tabet offers a potential way out of all this destruction, via free appropriation and reinvention. Material culture is a mirror of mortality, dependent for survival on creative reproduction.

Tabet also offers an original, if tangential, response to the predicament of architectural ornament today: Ornament has lost its ability to tell stories about society, or rather, society has all but lost the ability to receive and transmit the significance of ornament according to clear rules or conventions of representation. Globalization favors “universal” communication based on sensory or affective response.21 At the same time, contemporary art and architecture are responding to demands for localism and narrative. So Tabet flips the problem on its head. If ornament can no longer transmit meaning or tell stories, he tells stories about ornament. The narrative subjects are not just works of architecture, in all their contingency and impermanence, but also individuals and society. He imparts new meaning that is transparently subjective yet relatable. It’s his story, not the story. Real people, documents, and objects take the place of reductive generalizations. Specificity, with imagination, is one antidote to essentialism.

Since there is no such thing as timeless architecture or ornament, there is no way to fully recover and restore the “original” social significance of any historic ornament in situ. By the same token, no work can really be declared dead, which is to say closed to fresh readings and reworkings. That alone is reason enough to support the conservation of historic works and to immerse ourselves in adventurous stories about ornament.

-

All texts shown in the gallery and accompanying printed pamphlets are in two languages—English and Arabic—consistent with director José Esparza Chong Cuy’s practice of bilingual presentation for all exhibitions featuring international artists/designers. ↩

-

Jules Bourgoin’s Précis de l’Art Arabe was published in two virtually identical editions by Ernest Leroux in Paris. The first, in 1891, was issued as Volume 7 of the Mémoires publiés par les membres de la Mission archéologique française au Caire (“Memoirs published by members of the French Archaeological Mission in Cairo”). The edition that Rayyane Tabet recomposed in his Collages at Storefront for Art and Architecture is the second version, published in 1892 as a stand-alone work titled, simply, Précis de l’Art Arabe. ↩

-

Antoine Picon, Ornament: The Politics of Architecture and Subjectivity (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), 151. Picon goes on to say that in a computer-driven design world, we should recognize that “Elementary operations like bending, twisting or folding… just like certain fundamental types of textures, patterns and topologies” may carry symbolic significance, much as the Classical orders once carried significance. “This is already the case with neo-Islamic patterns, which are so often used for projects in the Muslim world. To acknowledge openly their symbolic resonance represents perhaps the best antidote to the return of naive Orientalism.” ↩

-

Bourgoin, Précis de l’Art Arabe, 1. The preface opens with a picturesque watercolor perspective by architect Ambroise Baudry depicting a fourteenth-century minaret looming over the bustling Souq al-Asr market in Cairo. « Nos descendants ne connaîtront plus les souvenirs enchanteurs qu'elle a laissés à ceux qui ont pu la voir et l’aimer avant que le progrès moderne y eut développé son œuvre de transformation rapide et de vandalisme inutile. » Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s own. ↩

-

Gülru Necipoğlu and Alina Payne, “Introduction,” in Gülru Necipoğlu and Alina Alexandra Payne, eds., Histories of Ornament: From Global to Local (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 2. The full quote reads, “Itself a millennial global tradition with local variants, Islamic ornament has long been essentialized as a timeless phenomenon collapsed into reductive taxonomies of the arabesque.” The authors add that while many recent revisionist studies have challenged the oversimplified polarization between figurative art of the Latin West (in the medieval and early modern period) and supposedly aniconic or abstract Islamic art, “the vitality of the older essentialist stereotypes has not abated, especially in popular venues such as some exhibitions, museum displays, and survey books.” ↩

-

Jules Bourgoin, Les Éléments de l’Art Arabe (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1879), 5. « Élégance et complexité par des involutions géométriques plus ou moins distinctes ou mêlées, et construites avec symétrie. Des figures abstraits, la flexion linéaire et une sorte de croissance organique. » ↩

-

Bourgoin, Les Éléments de l’Art Arabe, 6. « De ce que l’inspiration de l’Arabe est sèche et purement abstraite, il résulte que son développement intellectuel ou artistique est resté peu varié et n’a pas eu d’ouverture sur des horizons nouveaux. De ce que la matière est ouvrée sèchement et brièvement, il résulte que l’art décoratif arabe est resté simple et nu, mais pourtant d’une élégance incomparable, parce que l’accord est parfait entre l’inspiration et l’exécution, entre le thème et le décor. » ↩

-

The quotation is attributed to Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, who from 1814 held the first academic post for Chinese studies in the West, at the Collège de France. Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, source unknown, quoted in Jules Bourgoin, Théorie de l’Ornement (Paris: A Lévy, 1873), i. « Il sera trop tard pour étudier les hommes quand il n'y aura plus sur la terre que des Européens. » ↩

-

Albert Gayet, L’Arte Arabe (Paris: Ancienne Maison Quantin, Librairies-imprimeries réunies, 1893), 7. « Cette inaptitude artistic du sémite… » ↩

-

Gayet, L’Arte Arabe, 5. « L’Arabe n’a jamais été artiste. » ↩

-

Gayet, L’Arte Arabe, 6. « Les principaux traits de son caractère, de ses mœurs et de son genre de vie ne différaient en rien de ceux qui ont été siens à l’époque de Mahomet ou qui le sont encore aujourd’hui. » ↩

-

“A Guide to the Exhibition,” Rayyane Tabet: Alien Property, Metropolitan Museum of Art, link. The show is open until January 18, 2021, at the Met Fifth Avenue, New York, NY. ↩

-

With regard to the number of reliefs said to reside in each location, there are a few discrepancies between Tabet’s nine-page “Spy Story” transcript and the one-page chronology of the Tell Halaf reliefs, both published by the Met as part of the Alien Property exhibition. ↩

-

Richard W. Longstreth, Julia Morgan, Architect (Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, 1977), 29. ↩

-

Richard W. Longstreth, “Statement of Significance,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. San Francisco: The American Society for Eastern Arts, 1973. Courtesy of United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, link. ↩

-

Cary James, Julia Morgan: Architect (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 1990), 101. ↩

-

James, Julia Morgan, 76. ↩

-

Longstreth, Julia Morgan, 11. ↩

-

Taylor Coffman, Hearst’s Dream (San Luis Obispo, CA: Ez Nature, 1989), 43–35. Hearst wrote to Morgan in 1919 of his increasing certainty that “the Renaissance style of Southern Spain” was a more appropriate inspiration for his new home than Spanish Baroque or early California Spanish mission precedents. “We picked out the towers of the Church of Ronda. I suppose they have some Gothic feeling; but a Renaissance decoration, particularly that of very southern part of Spain, would harmonize well with them. The Renaissance in Northern Spain seems to me very hard, while the Renaissance of Southern Spain is much softer and more graceful.” Morgan replied with some thoughts of her own but generally agreed. The historian Coffman adds, “In any event, Southern Spanish Renaissance was the choice. From that premise William Randolph Hearst and Julia Morgan eventually created for San Simeon a style distinctly Mediterranean in spirit but a style that has never lent itself to more exact nomenclature. Attempts at codification have ranged from the coy to the serious—from Early Hollywood to Spanish Colonial Revival—yet none of them has quite hit the mark” (45). ↩

-

James, Julia Morgan, 80. ↩

-

Necipoğlu and Payne, Histories of Ornament, 2. “The former emphasis on culturally coded languages or ornament and decorum is being replaced by new engagements with surface, affect, and digital culture in a virtual age seeking to make the frontiers of art and cultures more fluid. These strategies privilege direct sensations capable of generating open-ended resonances and affects… accompanied by the utopia of universal visual communication.” Still, the authors suggest, the historic residue of symbolic ornament “may yet prove to be at work subliminally” in the theories and approaches that dominate today. ↩