We call for all people who participate in our networks as participants, volunteers, donors, researchers, activists, to always have in mind that we are all witnesses and organizers at the same time…

Thus, as active participants of the healthcare social movement and in every way we can, we should be documenting this unprecedented moment that our social movement is being formed and, at the same time, organize our struggle to address larger political questions of care, class, and access right now.1

—Third Panhellenic Assembly of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies, November 2013

The third Panhellenic assembly of solidarity clinics and pharmacies took place in November 2013 in the auditorium of the occupied “Elpis” General Public Hospital of Athens. Holding the assembly at Elpis was a symbolic and political act of solidarity: The hospital’s medical staff was at the time on strike, protesting the “catastrophic effects of the austerity policies” on the operation of health care infrastructure.2 Representatives and participants from all over the country had gathered to draft the “10-Point Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies.” Acting as a strategy document, the Charter of Constitution outlined the codes and ethics of a “network of social protection built to counteract any form of state violence that was reproduced and exacerbated through austerity.”3 The ultimate aim, as described in the charter’s introduction, was to build “an archive of resistance.”4 Intent on registering the social movements around health care in Greece, the archive would record and collect testimonials from activists engaged in the struggle against mass deprivation—a struggle that continues to transform and retransform the city.

Solidarity clinics and pharmacies formed in Athens as a way to serve the 33 percent of Greece’s population without insurance and the hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants and refugees excluded from the national health care system.5 Emerging in response to the global financial crisis of 2008 and out of the subsequent wave of “commoning” projects devised to contest the brutality and the social and economic asymmetries of austerity, solidarity clinics and pharmacies have moved to occupy the infrastructural gaps and welfare architectures vacated by the state.6 As mutual aid projects delivering primary medical care and pharmaceutical access to those continually marginalized, they are a powerful example of “health solidarity”: “the willingness of ordinary people, activists, and unemployed medical staff to build structures of solidarity to cope with the devastating and dangerous consequences of austerity and the liquidation of the public welfare system.”7 Writing on the forms of counterlife developed “in the face of the zones of state abandonment,” Elizabeth Povinelli has unveiled the importance of collectively (re)acting in the present—as the “event of abandonment” takes place—to make visible governmental strategies of abandonment that exclude and exhaust marginalized populations: “Progressive activism invests in the endurance of life in spaces of state and social abandonment because these spaces are capable of providing a potential for cultivating a new ethics of life and sociality.”8 Building and sustaining alternative social worlds unfolds in spatial, material, and temporal ways. However, as Povinelli also reminds: “If we must persist in potentiality, we must endure it as a space, a materiality, and a temporality. As we all know, materiality-as-potentiality is never itself outside given organizations of power.”9

Thus, Greece’s network of solidarity initiatives builds out spaces for care and builds up strategies for their continued existence. At the heart of the solidarity clinic model is the relationship between its archive and its architecture. Or, to it put differently, the “archive of resistance” that it is constructing and assembling exists in the city and in documents, in material resources and in knowledge. The solidarity clinic and pharmacy both draw upon and give back to the urban experience of care during times of crisis, expanding the range of protocols available for producing and reproducing durable social protections and relief in the midst of neoliberal assault. This creates spaces where the process of care stops being singularly about the caregiver and care-seeker and instead becomes an assemblage of resources, media, equipment, practices, and affects, of “participants, volunteers, donors, researchers, activists”: the site of medical practice but also the site of social-movement-building. This dualism allows solidarity clinics and pharmacies to endure in space, and lays the ground for their future expansion and continuation.

Producing Solidarity Health Care

The activities of social solidarity economy… are developed either within the market economy or through autonomous networking outside the private market. With the voluntary bidding of participants, they seek to meet the social needs of people who are not satisfied by the state or the private market and thus participate in the aforementioned structures, while claiming increased social participation or the active support of the state to the social needs they seek to cover.10

––Explanatory Statement of the Law on Social and Solidarity Economy, October 2016

The first solidarity clinic in Greece was conceived in 2011 as a “solidarity project” of the popular assembly in Athens’ Syntagma Square, just opposite the Greek parliament. As a collective microstructure supporting the Aganaktismenoi (anti-austerity) movement, it provided first aid to protesters out of a tent in the square, envisioning an alternative mode of care founded on the principles of direct democracy.11 In the years that followed, solidarity clinics and pharmacies sought more permanent and diffuse interventions across Athens—occupying less central (sometimes less visible) sites across the city. What has emerged today is an independent network of health care provision—solidarity clinics, solidarity pharmacies, and architectures that combine the two—dispersed across the city in the unused commercial and domestic sites hollowed out by the financial crisis.

Between 2008 and 2013, the burden of private debt increased 10 percent according to the EU, greatly affecting Greek property owners and the very fabric of the city.12 With millions of taxpayers in Greece indebted to the tax office, declaring private property as inactive and vacant provided a way to avoid forced foreclosure. Because of the vital function they served to the public, many solidarity clinics and pharmacies were granted meso- or longer-term use of empty state-owned properties throughout the city—as part of a larger effort by the SYRIZA party to concede “small property of the state”—public property below 100 square meters—to “the agencies of the social solidarity economy.”13 The goal, as articulated by deputy minister of labor, social insurance, and social solidarity Theano Fotiou (who is also an architect), was “to establish a radical strategy for shelter and housing provision through the evaluation of the so-called small property of the state for the housing of vulnerable groups of the Greek population, refugees and unaccompanied minors, but also of social agencies and solidarity bodies and other agencies that have a humanitarian and environmental value.”14

Yet this practice of cooperating with the same government that had caused the displacement of so many building residents has become divisive among solidarity clinic organizers.15 As a result, many solidarity clinics instead occupy private buildings or apartments that are either granted to them for free or for which they pay rent to private landlords.16 In most cases, however, solidarity clinics pay rent in the form of covering utility bills and undertaking maintenance work. Moreover, either the landlord or the collective of the clinic, depending on the agreement, are able to apply for tax relief as an act of reciprocity by the state.

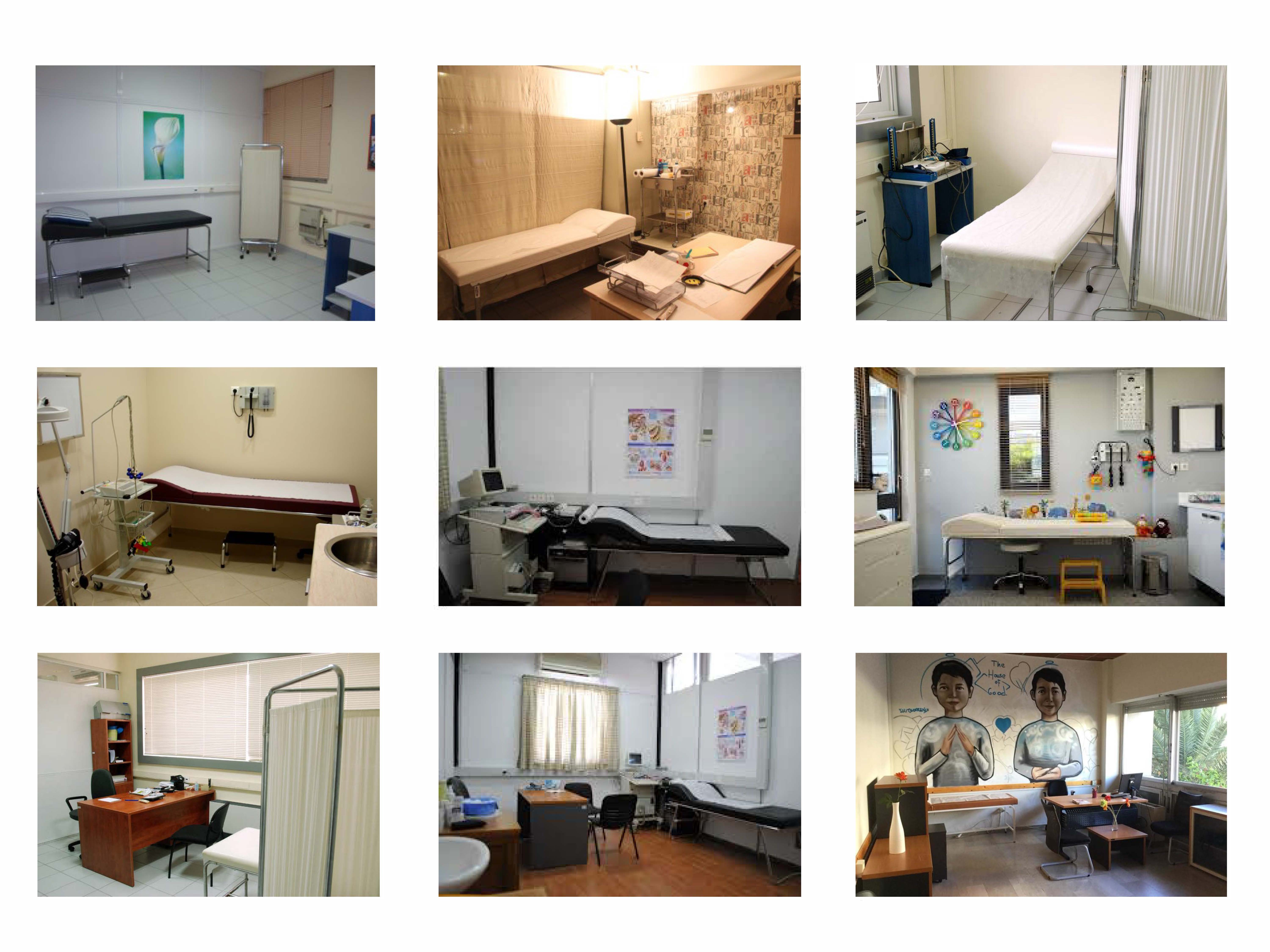

This has reinterpreted and recomposed the architectural and urban syntax of Athens, creating and recreating conditions for everyday life. For both solidarity clinics and pharmacies, it is not just the intended use of space that governs the spatial configuration of care but also the care protocols and their respective medical equipment (all of which is donated) that reproduces the space around them. Larger clinics like the Social Clinic and Pharmacy of Solidarity of Athens (KIFA.A) and the Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon (MCCH)—the latter of which is located in a building owned by the Municipality of Hellinikon-Arghiroupolis––have retrofitted the buildings to accommodate a host of uses: fully equipped surgery rooms for minor surgeries and dental procedures, multiple medical examination rooms, changing rooms, storage space for supplies and pharmaceuticals, administrative offices, waiting rooms, kitchens, and bathrooms. Through the support of the local community, shops, and businesses, solidarity clinics have managed to reconfigure the spatial arrangement of the spaces they occupy: building partition walls, providing new energy and electrical supply sources, and maintaining the medical equipment they own. Often, local businesses volunteer to provide professional help to build out the medical facilities of solidarity clinics. Otherwise, the work of builders or engineers is paid from agreements supported by the organization Solidarity for All or from the donations of local and international solidarity activist groups.17 As solidarity clinics have had to adapt to a range of preexisting, nonmedical spaces throughout the city, medical care often takes place within half-emptied living rooms, bedrooms, and corridors. Moving through domestic interiors, this caregiving practice has generated a new interface between inside and outside, transforming private domains into the public sphere.

The spatial needs of solidarity pharmacies come with their own specific requirements. The National Association of Pharmacists in Greece stipulates that pharmacies must operate on the ground-floor level and under the supervision of at least one professional and licensed pharmacist.18 In 2017, these standards were extended to solidarity pharmacies and any other extra-state organizations that provide pharmaceuticals in Greece, amid tensions between the National Association of Pharmacists and the Ministry of Health in 2017 regarding the legality of solidarity pharmacies.19

Not all solidarity pharmacies have managed to secure (permanent) ground-floor space and as a result have had to shift their function—becoming “storage” spaces responsible for distributing supplies and pharmaceuticals to operating pharmacies in the network. This was the case with KIFA.A.’s pharmacy, which was initially housed in a ground-floor apartment in Athens (with the clinic located in another apartment above it on the second floor).20 Both apartments belonged to a private landlord who was also a volunteer doctor at KIFA.A. In 2016, however, its assembly made the decision to seek a more permanent space and relocated to the third floor of a former office building in the center of the city. Today KIFA.A ceases to have a functional pharmacy and instead focuses on redistributing medicine to other organizations in need of it. As Povinelli reminds us, “materiality-as-potentiality is never itself outside given organizations of power,” but despite the regulations solidarity pharmacies are subject to as service providers, this dual practice of occupying space ad hoc and archiving of resources manifests as a form of redistribution and reproduction allows this self-managed system to persist.

Reproducing Solidarity Health Care

A team at MCCH has been compiling an oral history of our clinic. Talking with patients and volunteers, they are collecting experiences and incidents lived and witnessed at our clinic. The goal for this collection is not only to document what we have done, but also to help chart the future direction of MCCH as well as other solidarity based organizations might take in the future.”21

––Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, Public Statement, January 18, 2020

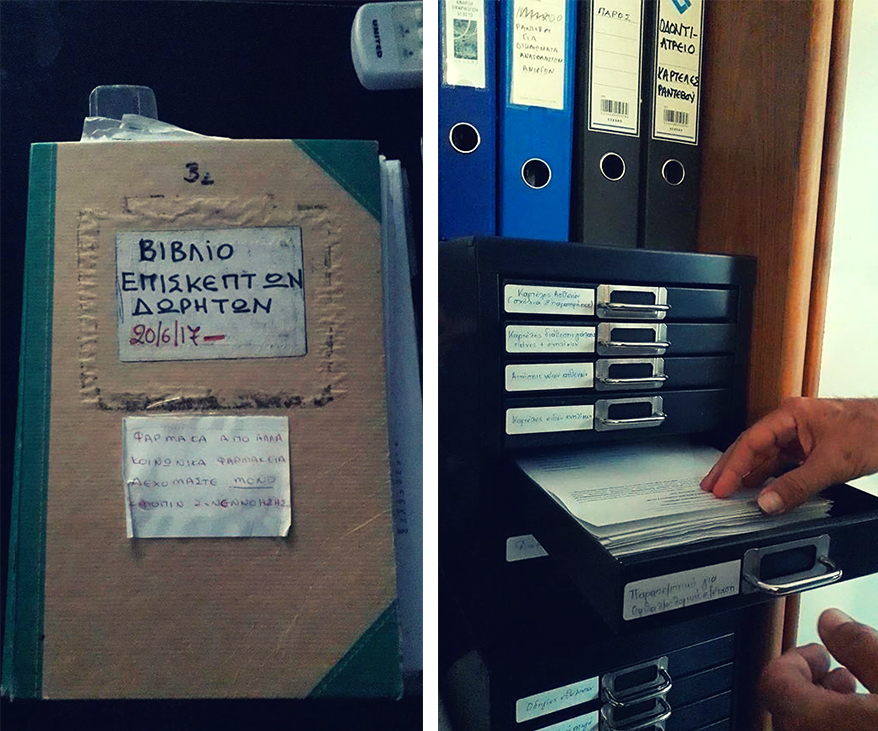

Distribution and redistribution of resources but also of tactics, strategies, and knowledge is a crucial practice among solidarity health structures. Many solidarity clinics and pharmacies document and share their activities, experiences, resources, alliances, spatial configurations, and maintenance protocols with the entire self-organized network of solidarity initiatives in Greece.22 The typical archive of a solidarity clinic consists of bills and cost templates, shift schedules and medicine catalogs, inventories of equipment and sketches of spatial layouts, architectural drawings of the property and photographs. The solidarity clinic redistributes health care activities, including medical care provision, as well as the redistribution of all the objects and technology linked with this alternative health care infrastructure. This includes an economy of furniture, sophisticated medical equipment, manuals for the maintenance, repair, or building of your own medical items (e.g., disposal bins). It is the diffused nature of the solidarity clinics, and the fact that knowledge, skills, and protocols are transferred within and between the initiatives that are part of the solidarity network, that substantially increases their endurance.

Practices of solidarity and mutual aid depend on these resources, as the ability to access, draw upon, and protect them defines the durability of these initiatives in the short and the long term. As an active, open archive, solidarity clinics preserve their network by broadening the system of circulation between caregivers and seekers, distribution of medicines, and communication between doctors and volunteers. If a care-seeker is given a doctor’s certificate or a prescription for medicine at a solidarity clinic, they can visit any solidarity pharmacy to fill that prescription. Solidarity clinics also recognize the need for extending the care they provide to other solidarity initiatives operating in the same neighborhood. It is not uncommon, especially in vulnerable areas in the city center or middle-class neighborhoods across Athens, for a set of solidarity projects—which provide access to health care, housing, and food, for example—to depend on one another.23

Within this intertwined infrastructure of care, the “interior” of solidarity clinics and pharmacies operates less as a set of discrete spaces and rather as a kind of spatial index that generates mutable and transferable protocols, designs, tools, and relationships. The solidarity clinics and pharmacies are in and of themselves counter-archives—records of possibility—which contain the tools to contest the architectures of abandonment by the state. Nevertheless, the interventions by solidarity clinics are never fully outside of the state’s grasp, as they are always subject to its laws, reforms, or policies. But despite this inevitability, the counter-archive allows the solidarity clinics and pharmacies to challenge existing forms of knowledge and care production that are carried out by public and private institutions—linking their radical practice of direct action to a material operativity that supports social reproduction in the context of austerity and crisis.

For Silvia Federici, this network of solidarity initiatives represents a vital act of reciprocity, a life-giving force: “For millions of people, and especially for people of color, neither capital nor the state provide any means of reproduction—they exist only as repressive forces. So many have begun to pool their resources and create more collective forms of reproduction as the only guarantee of survival.”24 Federici demonstrates how the only officially “viable” pathways to self-determination—access to state services, to capital—become weaponized against the marginalized, and so solidarity movements have no other recourse than to invert these means of social reproduction, making what is highly intangible and individualized highly material and collectivized. This is perhaps another way to read the archival efforts of the solidarity clinics and pharmacies that use the counter-archive as a means to collectively subvert the system of social reproduction of the capitalist city. The archive acts as a generator “for the development of new solidarity structures” and “the exchange of experiences” but also of all the tools and resources that build out the materiality of these structures.25 In this way, the archive is oriented toward building a different future of care: emphasizing, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore writes “a more active and general practice through which people use what they have to craft ad hoc and durable modes for living and for giving meaning to—interpreting, understanding—life.”26 For Gilmore, precisely “the awareness of imminent and ineluctable change that comes with abandonment in new ways and at new scales, opens up the possibility for people to organize themselves at novel resolutions.”27 The conditions of constant change that mutual aid projects have to navigate reflects on the continuous transformation of the extra-state aid system that solidarity clinics are part of.

For example, the solidarity clinic’s resources are entirely covered through donations from individuals and other solidarity groups, as well as from the GIVMED platform, a nonprofit startup largely powered by volunteers that was formed to accelerate the collection of surplus medicine from individual households and, most importantly, from large companies.28 GIVMED has become intertwined with the activities of the solidarity pharmacies in Athens, allowing people to donate medicines to specific organizations or individuals in need, which became especially useful during lockdown. In this way, the platform became one more node in this extra-state aid system.

The first point in the 2013 “10-Point Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies” articulates this extra-state aid system—defining the collective identity of the solidarity clinics as “autonomous, independent, self-organized, and self-managed.”29 The charter is careful in drawing a line between charity initiatives (exemplified by NGOs or the church) and initiatives of solidarity. It clarifies that the solidarity clinic’s activities are driven “by the need of the people and not by volunteering as self-determination.”30 Participants in mutual aid projects by social movements may overlap with charity and NGOs in that “their participants critique certain social service models and believe in voluntary participation in care and crisis work”; however, Dean Spade further argues that “the critiques of public safety nets made by participants in social movements are not the same as those of neoliberals who take aim at public services in order to further concentrate wealth and in doing so exacerbate material inequality and violence.”31

Fearing co-optation of their tools and demobilization of their participants that most commonly lead to social movement dissolution, the MCCH does not accept monetary donations and also rejects resources from the state, drawing away from the state's tendency to favor reform over direct action to cope with the gaps in health care services.32 The fourth point makes clear the clinics “have no intention, nor is there any illusion about the possibility of substituting the state that is withdrawing from the responsibility of taking care of the health of the population.”33 When it comes to their relationship with institutional and political bodies, solidarity clinics find themselves in a precarious position of contestation that manifests in various forums—juridical, administrative, urban space, built environment, and so forth—as they are demanding “that the state assume its responsibilities” by aligning forces with local and international organizations to demonstrate the degradation of human rights in the country from 2008 onward.34

This letter is written for you to fully understand the consequences of the threatened eviction and closure of the Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon (MCCH)... MCCH is a self-organized solidarity organization. Since 2011 we have offered health services, medicines and medical supplies, baby formulas, milk and other services to our fellow citizens in need. At the height of the financial crisis, with three million uninsured people in 2014 and 2015, we offered primary health services and pharmaceutical services at an average of 1,500 cases per month. Overall, we have helped 8,000 individuals with over 72,000 visits.

–– Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, Letter to the Greek Government, February 21, 2020

Solidarity clinics and pharmacies are constantly having to assert and contest their territorial presence, infrastructural domains, and system flows.35 On February 21, 2020, the Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon (MCCH) in Athens wrote a letter to the Greek government in a final attempt to prevent its eviction from the space it had occupied for almost a decade, in a building granted to it by the Municipality of Hellinikon in the area’s “city center.”36 The battle over its forced displacement started in May 2018 when the Hellinikon A.E development company threatened the MCCH with eviction from its building to proceed with the development plans that aimed at transforming the area into the so-called Athens Riviera, with luxurious hotels and casinos.37 As argued by the letter, this strategy of displacement was seen not as an isolated incident but as a calculated move, structured and organized at a time when health care infrastructures were needed the most.38 Eviction became the main strategy of the central government to threaten the spatial expression of “health solidarity” in urban space. Using the threat of eviction against the very same premises that were granted by the state, the government aimed to suppress the growing mobilizations and protests organized by the solidarity clinics and pharmacies that contested the ongoing failures of the health care system during the pandemic.39 In the face of hostile critiques and internal party politics aimed at the government for allowing the degradation of its unused premises to be utilized for solidarity initiatives and squatters, the newly elected government of New Democracy promoted a new vision of financial growth. It fast-tracked the implementation of a new infrastructural model for the city that includes skyscrapers, coastal regeneration, and international business tourism promoting privatization over welfare provision infrastructures.

The MCCH demanded “an immediate and in gratis solution” to be provided by the local authorities, even if this meant relocating to a different space.40 In May 2020, the local municipality of Hellinikon proceeded with the eviction of MCCH on behalf of Hellinikon A.E Company. However, the clinic’s contribution in the health care infrastructure of the area was recognized by its three neighboring municipalities, all of which offered new space for the relocation of MCCH, which eventually resettled in the neighborhood of Glyfada.41

Despite these organized attacks against their constitution, practices of solidarity in health care continue to endure conditions of infrastructural contestation, while projects of mutual aid developed by solidarity initiatives ensure the continued participation in their networks. In this way, solidarity clinics challenge existing infrastructure, and in doing so the very limits of the institution as we know it. As stated in their charter, these clinics and pharmacies constitute first and foremost a radical experimentation of participation. Participation in this case is perceived not as a premeditated practice only to claim what the state must do but as a practice that performs new ways for caring based on situated needs and on struggles for a holistic understanding of what it means to live healthy lives. As new models of health care infrastructure, the solidarity clinics and pharmacies remap the way the city administers care and have given rise to different forms of collectivity, accessibility, sociability, and care during situations of extreme contingency, unpredictability, and crisis.

In this light, the solidarity clinic not only generated a political moment for redistributing its collected equipment, donated medicines, secondhand medical equipment, and blank examination certificates given from hospitals but also provided the complex organizational system on which infrastructural claims made by solidarity initiatives could depend.42 This is an important contribution in itself, as the infrastructure of the solidarity clinic expanded the possibility for the cultural reimagining of care and of the experiences that accompany care. As Silvia Federici recounts, “The question we posed is how to turn reproductive work into a reproduction of our struggle.” In many ways, the spatial, temporal, and material acts of building carried out by the solidarity health care initiative provide an answer to this question, which continues to reverberate in the Charter’s declaration: “solidarity as a way of life.”43

I acknowledge and thank, for supporting the project and for their boundless powers, the participants and volunteers of the following: KIFA.A (Social Clinic and Pharmacy of Solidarity of Athens), I am grateful for the discussions with Maria Giannisopoulou, Kostis Kokossis, Lena Kougea and Avra Papathanasiou; Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon (MCCH/MKIE), a special thank you to Petros Mpoteas; the Solidarity Network of Kallithea Neighbourhood in Athens, especially Thouli Staikou and Sotiris Charalampidis; the Solidarity For All initiative in Athens, a special thank you to Giorgos Hondros. I am also thankful to the archival staff of the National Archive of the Town Planning Authority in Athens – Institution of Mapping and Listing of Empty Buildings and Committee on Digitalisation, for their generous assistance.

-

From the Introduction of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. A version of the charter can be found here: link. ↩

-

As stated in the introduction of their charter, “with public healthcare spending by the state reduced by more than 40 percent while more than 3 million people were uninsured and excluded from any public healthcare service,” it became commonplace for the medical staff associations, unions, and assemblies of hospitals to go on strike. These strikes made visible to the entire nation the dismantling of the most essential welfare provision. The first occupation of a public hospital in Greece was in 2012 at the “Kilkis” General Public Hospital in northern Greece. It was declared a self-managed hospital by the assembly of doctors and medical staff. See Fotini Lampridi, “Occupation and Self-management from the Workers of the General Hospital of Kilkis,” TVXS (February 29, 2012), link. ↩

-

From Point 4 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

From the Introduction of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

Charalampos Economou, “Impacts of the Financial Crisis on Access to Healthcare Services in Greece with a Focus on the Vulnerable Groups of the Population,” Social Cohesion and Development 9, no. 2 (2014): 99–115. See also, Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “Austerity Kills—These Are the Results,” link. ↩

-

For a view on the events that led to the creation of commoning projects in Greece, see Alexandros Kolokotronis, “Building Alternative Institutions in Greece: An Interview with Christos Giovanopoulos,” Counterpunch, link. Commoning projects that began in the squares include boycotts, solidarity actions, alternative financing (e.g., crowd funding, food banks), collective purchasing groups, occupations, self-management, free legal advice, medical services, communal cooking, “no intermediaries” markets, time-banks, collective solidarity support schemes for housing, legal advice, and anti-eviction, based on broader political claims and practices of collectively making a living. See Giorgos Kallis and Angelos Varvarousis, “Commoning Against the Crisis,” in Another Economy Is Possible: Culture and Economy in a Time of Crisis, ed. Manuel Castells (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), 128–159, link. ↩

-

A comprehensive overview of the effects of austerity policies in Greece can be found in the groundbreaking report released by Solidarity for All, “2014–2015 Report, Building Hope against Fear and Devastation,” 17, link. Solidarity for All categorizes the grassroots solidarity movement that has developed since 2008 as manifesting in “health solidarity,” “food solidarity,” “Social and Solidarity Economy,” “housing, debt, and legal support,” “solidarity tutorials and cultural centers,” “workers’ solidarity,” and “migrant and refugee solidarity networks.” ↩

-

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 127–128. ↩

-

Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment, 128. ↩

-

Explanatory Statement for the law “Social and Solidarity Economy and Development of Its Agencies and Other Provisions” (N9295, Government Gazette Ν.4430/2016 – FEK 205/Α/31-10-2016) proposed by the Ministry of Labour, Social Insurance and Social Solidarity in 2016. See link. ↩

-

The mass anti-austerity protests in Greece in 2010–2011 occurred alongside the Indignados movement in Spain and Occupy Wall Street in the United States, which together encompassed the “Movement of Squares.” Protesters occupied the central squares of Athens and public spaces across Greece. Solidarity for All reports that almost one-third (28 percent) of those living in Greece participated in the movement. See Kallis and Varvarousis, “Commoning Against the Crisis,” 136. ↩

-

See European Commission, “First Program for Greece,” link. ↩

-

Legislated by the SYRIZA government as part of the law on Social Solidarity Economy (Law Ν.4430/2016), unused public property was granted to “the agencies of the social solidarity economy” for them to reconfigure it for “social and environmental benefits and deal with the humanitarian crisis.” Since 2008, more than 300,000 empty public properties are registered in the Greek government’s registration systems according to a report by Opengov.gr: link. ↩

-

Fotiou’s statement was delivered at an event organized by SYRIZA in April 2017. The statement also appears in Sotiris Beskos, “Public Real Estate Will Be Granted to Those Who Do Not Have It, Says Fotiou,” Dikailogitika, April 26, 2017, link. ↩

-

Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment, 128. ↩

-

Notes by the author from a discussion with Kostas Kokossis (writer) and Maria Giannisopoulou (social anthropologist), two volunteers with the archival and administration team of KIFA.A. ↩

-

National Association of Pharmacists in Greece, “About Social Clinics,” August 23, 2017. This decision was supported by the Region of Attica, which was monitoring its implementation in the urban space of Athens. ↩

-

KIFA.A (Social Clinic and Pharmacy of Solidarity of Athens), “Social Solidarity Clinics: Their Role Today, Yesterday and Tomorrow,” October 11, 2017, link. ↩

-

Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “Going Deep, Exploring Our History,” link. ↩

-

As stated in Point 8 of their charter, solidarity clinics and pharmacies “intend to collaborate with food solidarity structures such as solidarity groceries, exchange bazaars, and markets without middlemen in direct collaboration with producers of agricultural products,” and “generally any self-organized initiative that contributes to social relief and access to social goods for all.” ↩

-

Doctors from the solidarity clinics have also set up medical examination rooms and pharmacies in various buildings of other solidarity projects to provide medical assistance for refugee accommodations, such as the housing provision set up in the former City Plaza hotel in Athens. Olga Lafazani presents an empirical account of building solidarity for the Refugee Accommodation and Solidarity Space City Plaza from different social movements. Olga Lafazani, “The Multiple Spatialities of City Plaza: From the Body to the Globe,” New Alphabet School HKW, June 2021, link. ↩

-

In Silvia Federici and Marina Sitrin, “Social Reproduction: Between the Wage and the Commons,” Roarmag 2 (2016): 4, link. ↩

-

Points 7, 8, and 9 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies clearly demonstrate that the clinics both “support initiatives for the development of new solidarity structures and seek the exchange of experiences.” ↩

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning,” in Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship, ed. Charles R. Hale (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008), 37. ↩

-

Gilmore, “Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning,” 36. ↩

-

GIVEMED found success by raising awareness about the consequences of surplus, deficit, and leftover medicine for the environment and the poorest population in the country. Medicine Share Life GIVMED platform, link. ↩

-

From Point 1 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

From Point 2 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

Dean Spade, “Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival,” Social Text 38, no. 1 (2020): 140. ↩

-

From Points 4 and 5 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

From Points 4 and 5 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

-

Hellenic League for Human Rights, “Downgrading Rights: The Cost of Austerity in Greece,” International Federation for Human Rights 646a (2014), link. ↩

-

Massimo De Angelis, Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism (London: Zed Books, 2017), 27. ↩

-

The letter addressed not only the Greek parliament, but also the United Nations and the European parliament. See Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “Letter to the Greek Government,” link. MCCH had occupied the building in Hellinikon from its inception in December 2011 until its eviction in June 2020. The property used to be an ancillary building for the former American base of the US Air Force and was located next to the Community Social Centre of Hellinikon that was also evacuated, and its relocation is still in progress. ↩

-

The skyscraper designed by Foster + Partners will be built in the same area of the “Metropolitan Centre” of Hellinikon. See also Lizzie Crook, “Foster + Partners Reveals Plans for Greece’s Tallest Skyscraper,” Dezeen, July 8, 2021, link. ↩

-

Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “Letter to the Greek Government,” 2020. ↩

-

Eviction letters were also sent to the solidarity clinics of Nea Filadelfeia and Thermi. See Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “Solidarity to the Social Clinic of Thermi, Social Solidarity Clinic-Pharmacy of N.Filadelfeia, N.Chalkidona, N.Ionia,” link. ↩

-

Metropolitan Community Clinic of Hellinikon, “We Go On Because the Need Is Still Great,” link. ↩

-

It is important to distinguish the power that local administrations have from that of the central government and how, as such, they can play a crucial role regarding the expansion and intensification of solidarity initiatives as most of them are tied to their neighborhoods. On the whole, local administrations act on the basis of political representation, electoral politics, and local power, and their policies can vary from district to district: this is also the case for Athens. ↩

-

For Jacques Rancière every political moment involves the incalculable leap of those who decide to demonstrate their equality and organize their refusal against the injustices that promote the status quo. In Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), 9. ↩

-

From Point 2 of the Charter of Constitution of Solidarity Clinics and Pharmacies. ↩

Elisavet Hasa is an architect and educator. Her recent research draws on the social movements of the last decade that provide support to marginalized groups as a form of collective direct action to investigate how they create micro-infrastructures for care provision and interrelate in various forms with state institutions. Elisavet is a founding member of Fatura Collaborative, an architecture and research practice, and a PhD candidate in architecture at the Royal College of Art in London.