Devon House is a tourist destination. Docents at the house work in a wealthy part of Kingston among walled streets and gated compounds, including Jamaica House, the prime minister’s official residence, as well as the Bob Marley Museum (in the musician’s former house). Wearing period-inflected servants’ attire, the tour guides inform visitors that the building was commissioned by George Stiebel, Jamaica’s first Black millionaire. The 1881 mansion, despite its classical detailing, bears comparison to its ostentatious contemporaries in Newport, Rhode Island, or to the illustrations in Mark Girouard’s The Victorian Country House.1 Flanked by gift shops, a restaurant in back, and a manicured yet lush Caribbean landscape in front, the whole affair lends itself to touristic projection: an imaginary fantasy of wealth after slavery, no longer predicated on racial exploitation or oppressive imperialism. At the end of their tour, visitors receive a ticket for a free ice cream cone, made on the premises and featuring local specialties like rum, raisin, and coconut. A light piece of travel journalism in a 1984 issue of Jamaica Journal called it “The House of Dreams.”2

The Caribbean economy relies on tourism.3 Predicated on an ambivalence between concrete objects and conceptual visions, tourism is an industry that deliberately conjures images so that paying customers might temporarily suspend reality and live out their desires. This is what the scholar Malcolm Ferdinand, in his 2019 book Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean, sardonically calls “the search for paradise on Earth that conceals the other’s existence”—a pursuit that brings together colonizers and environmentalists alike.4 Devon House occupies a peculiar place as a representation of an idyllic, post-emancipation, racially untroubled Jamaica—or, at least, as a site that presents an uplifting narrative. The house, acquired by the Jamaican government in 1967, five years after independence from the British Empire, embodied a newly available nationalist allegory of self-determination, self-sufficiency, and enterprise. Yet the building’s restrained neo-Georgian classicism also suggests a savvy reconfiguration of the aesthetic motifs that predominated during the heyday of British colonial rule. That is, the classical paradigm conveys a sense of repurposing the “master’s tools,” a combination of retort and insecure bluster that, indeed, the Jamaican Black capitalist could build his own mansion despite continued British imperial imposition.5

While George Stiebel was not exactly a colonizer, Devon House bears all the traits of what Ferdinand identifies as “colonial inhabitation”: the site is enclosed (walled) and subordinate to Europe (its wooden columns and pilasters, triglyphs and metopes, and cornices suggest admiration for classical aesthetics, perhaps to the point of deference); it is “based upon the exploitation of the land and the nature of” the Caribbean; and it suppresses the possibility of an other in a complex process of assimilation that Ferdinand describes as “othercide.”6 Ferdinand’s focus is undoubtedly the epoch of chattel enslavement. Yet that all these features appear, albeit in modified form, in architecture built later and at the behest of a Jamaican Black man, corroborates the paradoxes of the Caribbean as a site of simultaneous freedom and exploitation, in what Ferdinand designates “plantationary emancipation,” or “the desire of becoming the master in place of the master.”7 The historical circumstances represented by the man who commissioned the house underscore those paradoxes. Stiebel was the son, born out of wedlock, of a German Jewish enslaver (whose seed money financed the future millionaire’s initial ventures) and a Black “housekeeper,” likely Elizabeth Hendry, whose designation as such suggests theirs was not an altogether equitable union.8 Stiebel had several London-born half-siblings, of whom at least two were male, whose mother was Eliza Mocatta, likewise from a family with Jamaican property interests.9 While Stiebel received a considerable bequest from his wealthy father, his half-brothers received the bulk of their father’s inheritance. Stiebel’s eventual capacity to leverage the funds he received into his conspicuous mansion was just one of the visible manifestations of “plantationary emancipation,” along with land acquisition, resource extraction, and labor coercion, to name a few.

In Decolonial Ecology, Malcolm Ferdinand indicts “the scholar who departs from the Global North and carries in his suitcase concepts that are to be experimented with in [sic] a non-scholarly Caribbean, before he leaves again with the fruits of this new knowledge, now capable of prescribing the way forward.”10 In contrast, Ferdinand proposes “an ecology of the enslaved,” which “shatters the environmentalist framework for understanding the ecological crisis by including from the outset... the world’s colonial fracture and by pointing to another genesis of ecological concern.”11 The Caribbean basin generated material wealth in Europe, and would later serve as a testing ground for industrial management.12 Pointing to these forms of racial capitalism as the defining feature of European extractive colonization in the Caribbean, Ferdinand argues that, for all its histories of exploitation and destruction, the region also provides models, and an ideal site, for reparative action. The archetype of the ship figures prominently in Ferdinand’s book, both as an instrument of oppression, the slaving ship, and as a rhetorical device that points toward salvation, the “World-Ship.” This latter formulation imagines an amicable encounter with others, reappropriating a scene of violence toward more just ends. Echoing Michel Foucault’s invocation of the ship as the “heterotopia par excellence,” Ferdinand locates ships’ significance in their “capacity... to concentrate the world within them.”13 The ship, however, is an ambivalent object for Ferdinand, ranging from the exclusion of Noah’s Ark to the violent segregation of the slave ship to the sanguine image of a “ship without a hold,” in which all are welcome on deck.14

With their constant presence in the Caribbean, cruise ships too exhibit those ambivalences, as machines of division and consumption. Contemporary cruise lines defer exploitation to regions of the Earth’s surface from which they extract fuel in a process concealed from complacent vacationers. Behemoth vessels burn some dozens of thousands of gallons of fuel per day so that passengers can occasionally alight dockside to experience local tastes and culture, such as Devon House.15 Le Corbusier concluded his giddy admiration of “liners” with the admonition: “The land-dweller’s house is the expression of an outdated world of small dimensions. The liner is the first stage in the realization of a world organized in accordance with the new spirit.”16 Although individual spaces on cruise ships may be small, communal areas are airy and well-lit, connected to exterior decks that reveal a vast, newly accessible “world” of exotic ports for passengers to visit, offering novelty every few days and at all turns. To be sure, a generalized moral condemnation of tourism, which certainly benefits Jamaicans and the Jamaican economy, would be reductive. But the story of wealth accumulation that “Jamaica’s first Black millionaire” proffers is equally simplistic. The buoyant myth corresponded to a so-called crown colony no longer under the yoke of racial enslavement, migrating from an economy that had been almost singularly dependent on sugar to one that engaged in other extractive industries, including fruit, minerals, and, of course, tourism.

Stiebel, the magnate behind Devon House, made his money from shipping. After initially training as a carpenter’s apprentice, his father, who received compensation for three people he claimed as property upon their emancipation in 1836, furnished him with the capital to buy a ship.17 He was imprisoned in 1844 for gunrunning in Cuba; some accounts have him escaping after bonding with his fraternal Freemason prison guard, while others suggest he was selling guns to enslaved people (during a period of successive, possibly connected uprisings collectively known as the Escalera).18 Although he was able to parlay his earnings into three ships, they were all wrecked in the 1850s. He survived, both literally (from the shipwrecks, according to the myth) and financially, to start a gold mining operation in El Callo, Venezuela, shortly thereafter: the Callas Gold Mining Company, which ended up yielding enough of a fortune to purchase a number of properties, including sugar estates and a wharf, as well as to commission Devon House.19

Later in life, Stiebel entered politics as a municipal leader, a member of the Kingston Board of Education, and the city’s gas commissioner. He also held several philanthropic positions.20 He lent the government funds for the 1891 Jamaica International Exhibition in Kingston, whose express purpose was to promote tourism (as well as agribusiness machinery).21 The exhibition building was modeled after the Crystal Palace but adapted for the context of colonial Jamaica. Other preparations for the event included a large-scale government-subsidized hotel construction program. Queen Victoria officially recognized Stiebel with an award as a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George for his contributions to the effort. As a politician, he participated in an advisory commission for a new, representative governmental structure in the aftermath of the 1865 massacre by the British colonial governor known as the Morant Bay Rebellion, which had been propagandized as the suppression of an unruly mob. He sought to expand the franchise to all men, regardless of race or economic means, advocating against an “educational test,” including literacy qualifications, as well as minimums in paid taxes (£1) and property ownership (nine acres) as prerequisites for political participation.22

Stiebel’s most prominent, enduring legacy, however, is Devon House. The house, located on a 53-acre estate in an area then on the outskirts of the city, does not exactly conform to the prevailing aesthetic trends of late Victorian architecture. In an essay on Victorian buildings in Jamaica, University of the West Indies historian James Robertson observes, “In impoverished Jamaica most new buildings erected during Victoria’s reign remained overshadowed by the architecture of sugar’s heyday.”23 Robertson acknowledges that, as a product of “private enterprise,” Devon House “could display considerably more flair.” The house itself, however, complicates those characterizations.

Where architects of the late nineteenth-century Euro-American bourgeoisie were elsewhere pushing against the boundaries of doctrinaire forms, Devon House is defiantly staid. Across the British Atlantic world, contemporary aesthetic trends ranged from garish Second-Empire Baroque, to orientalism and Arts and Crafts movements, to neo-Gothic, Carpenter Gothic, and neo-Romanesque forms, and hybrids of all of these. This variation is on display at colonial administrators’ residences in, for example, Manitoba, Canada (built in the early 1880s; mansard roofs, decorative brackets); Port of Spain, Trinidad (built 1844–1848, renovated in 1892, burned in 1893, rebuilt 1903–1907; Baroque details, lantern); Natal, South Africa (built as a private residence in the late 1860s; ashlar stone exterior walls, filigreed fascias); and the Falkland Islands (built 1845–1859; cottage style, stone, high pitched corrugated-iron roofs). In 1894, in Jamaica, Thomas Patrick Leyden designed and built the Gingerbread Gothic Invercauld and Magdala houses in Black River, on the island’s southeast coast, with decorative gable ends and fretwork balconies. Given this diffusion of aesthetics across the British Atlantic world, one cannot assume that Stiebel and the architect-builder he hired to construct Devon House, Charles P. Lazarus, were simply oblivious. Lazarus was an iron founder, engineer to the Kingston and Liguanea Water Works Company, and, like Stiebel, a local political leader.

Stiebel and Lazarus chose to build a neo-Georgian mansion. Other comparable Jamaican buildings with classical detailing generally were vestiges of the era of enslavement, like the Italianate Rose Hall (c. 1740s–1750s) or the pedimented, quoined, and Doric-columned Marlborough House (c. 1795), built for immigrants who had fled turmoil in St. Domingue. Stiebel’s capital facilitated a type of freedom to which no Jamaicans apart from enslavers had had access. This was not simply self-determination, but a concretized self-expression in the form of a grand estate; a power to manipulate land and environment, to create one’s surroundings.

With that power, Stiebel elected to emulate the aesthetics of his predecessors—Jamaicans who had capital, that is—by enclosing land (purchased from the St. Andrews Parish Church of England) and building in a manner that replicated the prior epoch, replete with materials and statuary shipped from Scotland.24 As Ferdinand writes, enclosure as a matter of marking private property is inextricable from claiming rights over others: “usurpation... accompanied by a set of symbolic gestures directed at... Europeans.”25 This is not to suggest that Devon House signified any sort of betrayal; indeed, one may interpret the house as an expression of alterity, appropriating Georgian classicism to convey self-empowerment, as any number of nouveaux riches have claimed trappings of the bourgeoisie in other contexts.

In this regard, construing Devon House as an embodiment of what wealth in Jamaica could look like without slavery is not just a matter of fiction but, rather, a projection of an alternative reality, proffering a hopeful image to a long-oppressed racialized working class. According to this interpretation, instead of a reproduction of colonial aesthetics, belying its air of dignified reserve, Devon House flamboyantly expresses the dream of social ascension beyond the state of colonial oppression. Beyond the simple gesture of a restrained classicism, its consequences imply Georgian architecture’s fundamental infeasibility absent colonial exploitation. Its innovations adapt that architectural paradigm to a Jamaican climate with construction from a hybrid palette of materials sourced both locally and from England, a Jamaican formal garden surrounding the house proper, and technical devices to contravene the inconveniences of heat, humidity, and hurricanes. Insofar as Georgian architecture did not exclusively belong to English builders and dwellers, the implication would be that Georgian aesthetics were undergirded by Caribbean production—and thus as much the province of the Caribbean as of the colonizer. Call it an act of reclamation, precluding any appeal to the oppressor to concede to pay reparations, or even apologize.26

Another tourist site a mile’s walk away from Devon House, Usain Bolt’s Tracks and Records restaurant and bar, presents a similar ambivalence: simultaneously replication-import and appropriation-seizure. Menu items are characteristically Jamaican, but advertising copy targets tourists. Sample the Jerk Pork: “No visit to Jamaica can be complete without a taste of jerk”; or have the Pan Chicken: “Just like roadside pan chicken, test out our version of this favourite”; or eat like a Rastafarian by ordering the Ital Penne with Pumpkin Rundown: “Vegetarians and non-vegetarians alike will love this wicked version of an ital pasta.”27 Its other branch, in Montego Bay, serves “Pickney’s Piks,” a children’s menu, indicating its prospective customer profile. Cynicism aside, though, one might genuinely admire Usain Bolt’s capacity to leverage his status as a world-famous athlete into a brand that extracts capital from eager vacationers by offering “‘nuff' vibes.” Introducing the model of a sports bar to Kingston, where few other similar venues exist, Tracks and Records innovates precisely by emulation, selling back to travelers a comfortable microenvironment in a setting that might otherwise feel foreign to them. A suitably recognizable atmosphere, replete with glossy surfaces, a downlit bar, faux-leather banquettes, and large-screen televisions, the interior architecture conveys visitors from the US back to a familiar type of space, with a touch of local flavor.

Like the bars on the cruise ships that transported some of the patrons to Jamaica, Usain Bolt’s Tracks and Records is a specific place and no-place—that is, a heterotopia. And yet, barring laments for a more “authentic” local culture, both the bar and Devon House represent the possibility of economic gain for Jamaicans—not just for Bolt, but also the cooks, back-of-house staff, and servers; and at Devon House, the maintainers and docents—who can, indeed, profit from willing customers. On a symbolic level, both the restaurant and the house represent Jamaicans’ capacity to achieve excellence, and to capitalize on it. They consolidate the power of national identity and individual accomplishment into spatial forms that might draw tourists, but, just as significantly, appeal to the imaginary of Jamaicans seeking models for their country’s future.

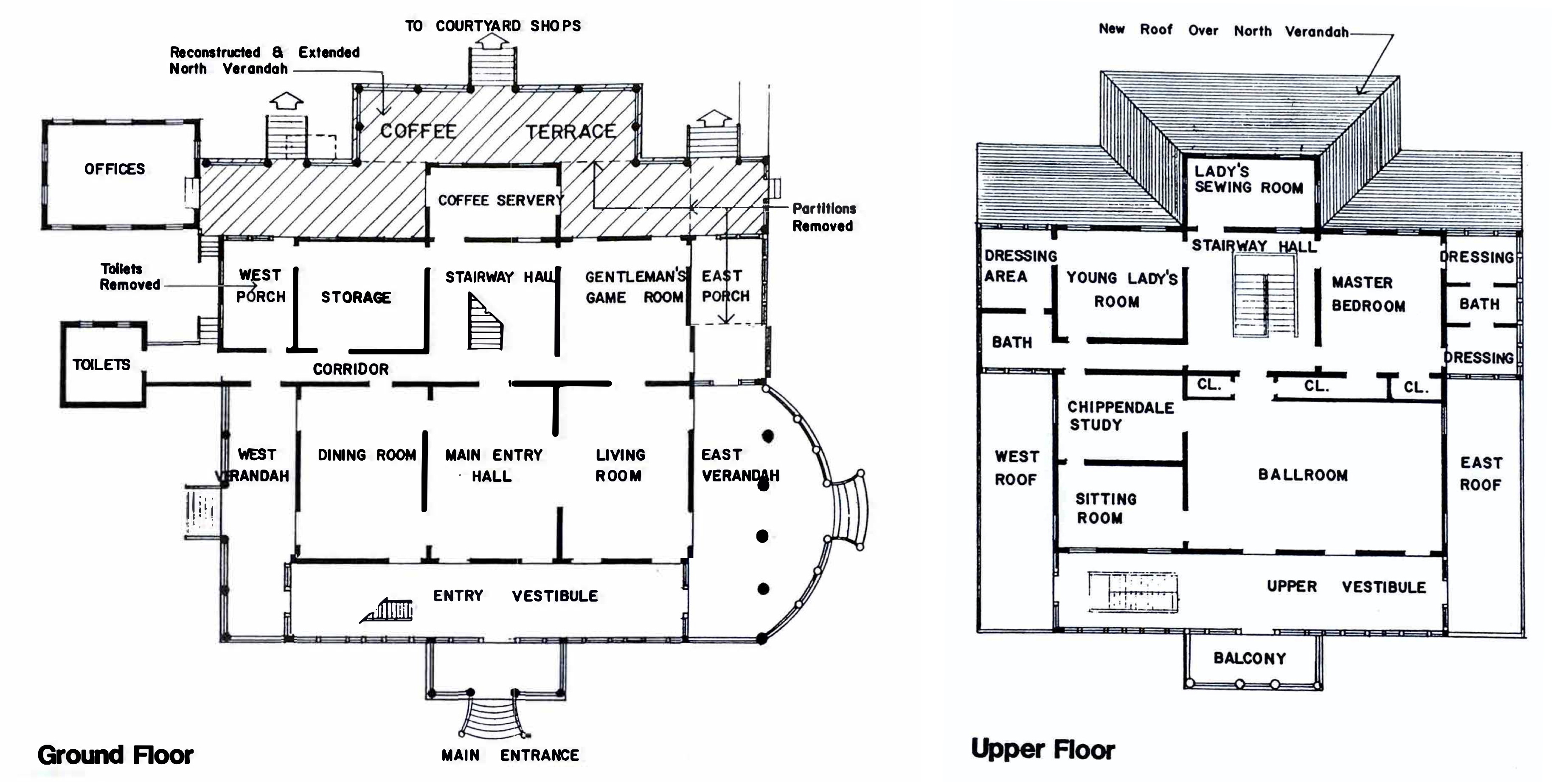

Amid this multivalence, however, Devon House undeniably stands as an image of wealth, not equality—and, indeed, of accumulation by an individual. Its size and abundance of rooms, configured to accommodate (paid) servants, indicate a lifestyle that would rarely be available to other Kingstonians. The house’s floor plans show an interior surrounded by buffering semi-outdoor porches and verandas. Inside, individual rooms have multiple doorways, enabling fluid passage of people and, notably, warm air, throughout the house. A central stair hall featuring a grand hardwood staircase connects the two main stories, but little space is otherwise devoted to circulation. Overall, the plans are organized in bands from front to back: a front vestibule (with a stair) stretching the entire width of the enclosed portion of the house; then a band with rooms with public functions (entry hall flanked by a dining room and living room); then the stair hall with a storage room and a game room to either side. Upstairs, the bands repeat: second-story vestibule; an opulent ballroom attached to a sitting room and study; and the upper stair hall, with bedrooms to either side connected with bathrooms in back. Large windows allow for ample ventilation throughout.

The featured interior space is undoubtedly the second-story ballroom, its wall panels in the style of Italianate grotteschi with vases and curling acanthus leaves, and a concave beige cornice adorned with plastered white swags and light-blue figural vignettes reminiscent of Wedgwood manufactures. According to Stiebel’s grandson, during crowded parties, cross-ventilation in the room was complemented by blocks of ice imported from Nova Scotia and placed in containers concealed underneath floral bouquets.28 Stiebel’s fortune from shipping and Venezuelan gold, in this case, was transmuted into environmental control by shipping durable and expendable commodities—brick, wood, iron gates, and ice—for a monument to luxury. From its detailing to its appurtenances, the house was an instrument to uphold persistent class structures.

Stiebel and Devon House were avatars for “enterprise,” a value held in high esteem by the Georgians and Victorians alike. As Ferdinand points out, “enterprise” has been and remains associated with both stewardship and extraction.29 The trope signifies a capacity to subjugate land and environment to the human will, corresponding to forms of possession that benefit the ruling class. Distinguishing between “those who inhabit habitations and those who reside in shacks,” Ferdinand explains, “The master’s habitation is meant to last... Today these ‘habitations’ are being transformed into museums throughout the Americas.”30 Among its many other paradoxes, Devon House’s location in Kingston develops such tensions. Stiebel was not a “master” or an enslaver. His father, a merchant, likely enslaved people because he had capital, not vice versa.31 Yet the house portrays a mirage of “enterprising” Caribbean wealth innocent of the dynamics of capitalistic deprivation. Ferdinand describes the gross inequalities of the Caribbean, perpetuated as “fantasies of paradise, today embodied by hotel plantations on the coasts, [which] coexist peacefully within poor countries marked by food insecurity and profound violence.”32 Kingston is not a cruise ship port on the order of Negril, Montego Bay, or Ocho Rios, with their all-inclusive travel packages offering tropical beaches, sun, and palm trees. A 2010 travel magazine article on Devon House began by acknowledging as much, calling Kingston “a tough city to love” due to persistent violent crime.33 Wealth disparities and dichotomies between “habitations” and “shacks,” in Ferdinand’s terms, are on clear display in the city, within walking distance of each other.

Other historic houses in Kingston and the rest of Jamaica and the Caribbean were, of course, scenes of far worse atrocities than the comparatively benign maintenance of class divisions that Devon House conveys.34 Therefore my intention is not to indict a Black Jamaican for his complicity in a system of wealth accumulation and retention that he did not construct and which he perpetuated solely through his participation in it. Even Stiebel’s active ventures in extractive capitalism pale against the exploitative practices of his robber-baron contemporaries.35 Yet his racialization (his wife’s parents objected to their marriage, supposedly on racial grounds; his paternal Jewish heritage likely also diminished his standing36) is what makes Devon House at once exceptional and revealing as a fragment of a Caribbean imaginary.

Despite the region’s productivity, postcolonial Caribbean states have been systematically denied the opportunity to retain wealth, largely due to legacies of exploitation and export of profits. These factors, combined with internal corruption, have been illustrated cogently in recent pieces of mainstream US journalism: a series of New York Times articles on Haiti’s “double debt,” imposed by France upon independence as recompense for loss of “property” in expropriated land and enslaved people; a New York Times/ProPublica feature on Barbadian negotiations to restructure the country’s debt in view of its outsize susceptibility to climate disaster; and a Vice News investigative report on Jamaican Maroon communities’ struggles against multinational corporations (specifically, a US-based one now known as Atlantic Alumina or Atalco) eager to mine aluminum ore no matter the ground surface damage or water pollution.37 Devon House is a material artifact that allows for a hypothetical: What would Jamaica look like if, instead of treating Jamaican land as a source of commodities to convert into fungible capital elsewhere, Jamaicans themselves had remained in control? Predicated on the same technologies of extraction, by reproducing the aesthetics of colonial grandeur, and in replicating familiar images of wealth, Devon House signals an imaginary fundamentally lacking in imagination. Ferdinand describes the complex of private ownership, plantations, and enslavement as “Colonial inhabitation,” which “creates an Earth without a world.”38 As Ferdinand explains it, this amounts to a commodification of resources and people alike. According to this mindset, “Earth” is a rhetorical figure that represents a capacity to harvest, quantify, and transform cultivation into profits, all while actively suppressing even an inkling that one might encounter subjectivities other than one’s own. Earth is all acquisition, but without the possibilities of either alterity or alternatives.

Ships are unique in their ability to allow societies to project other places.39 But when the dream is simply to assume the place of a dislodged superordinate, it is an indication that dreams have dried up. Despite the presence of (cruise) ships in the Caribbean, colonized people’s dreams, too, may be colonized.

-

Mark Girouard, The Victorian Country House (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), 54–55. ↩

-

Sergio Dello Strologo, “Devon House: The House of Dreams,” Jamaica Journal 17 (May 1984): 33–49. ↩

-

On tourism in the Caribbean, see Mimi Sheller, Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (London: Routledge, 2003), esp. 36–70; Sheller, Aluminum Dreams: The Making of Light Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), esp. 147–178; Frank Fonda Taylor, To Hell with Paradise: A History of the Jamaican Tourist Industry (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993); and Krista A. Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). ↩

-

Malcolm Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World, trans. Anthony Paul Smith (Medford, MA: Polity, 2022 [2019]), 100. ↩

-

Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984 [1979]), 110−113. See also Mimi Sheller, Democracy After Slavery: Black Publics and Peasant Radicalism in Haiti and Jamaica (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), esp. 145−246; Caroline Elkins, Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), 56−67; and Tim Barringer and Wayne Modest, eds., Victorian Jamaica (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 26−35; quotation on p. 28 (italics in text). ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 117, 122. ↩

-

See Michele Klein, “Wild Oats,” Shemot: Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain 28 (August 2020): 1−8, esp. 4. Enrique Martínez Ruiz identifies Eliza Catherine Bailey as George Stiebel’s mother, but Klein’s consultation of birth records appears trustworthy; see Enrique Martínez Ruiz, “Los Asquenazíes del Caribe: Redes Transatlánticas de Comercio y Migración entre Frankfurt y Bogotá, a Través del Imperio Británico en el Siglo XIX,” Historia Crítica 80 (April 2021): 57−79, esp. 61. ↩

-

The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History, ed. William D. Rubinstein, Michael A. Jolles, and Hilary L. Rubinstein (Houndsmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), s.v. “Stiebel, Sigismund”; “Sigismund Stiebel,” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership, University College London, link; Klein, “Wild Oats,” 4. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 12. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 13–15. ↩

-

See Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin Books, 1986), esp. 46–61; and Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), esp. 9–63. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16 (Spring 1986): 27; Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 22. Ferdinand addresses this concept: see Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 102−103, 186. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 187; Aurore Chaillou and Louise Roblin, “Why We Need a Decolonial Ecology: An Interview with Malcolm Ferdinand,” Green European Journal (June 4, 2020), link. ↩

-

Ed Davey, “Cruise Liners Try to Rewrite Climate Rules Despite Vows,” Associated Press (June 7, 2022), link; John Vidal, “The World’s Largest Cruise Ship and Its Supersized Pollution Problem,” Guardian (May 21, 2016), link. ↩

-

Le Corbusier, Toward an Architecture, trans. John Goodman (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007 [1924, 1928]), 158. ↩

-

“Sigismund Stiebel,” Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership; Klein, “Wild Oats,” 4. ↩

-

Enid Shields, Devon House Families (Kingston: Ian Randle, 1991), 18–19. ↩

-

Shields, Devon House Families, 20, 51. ↩

-

Shields, Devon House Families, 23−24. ↩

-

Shields, Devon House Families, 37. See also Wayne Modest, “‘A Period of Exhibitions’: World’s Fairs, Museums, and the Laboring Black Body in Jamaica”; and Belinda Edmondson, “‘Most Intensely Jamaican’: The Rise of Brown Identity in Jamaica,” both in Barringer and Modest, Victorian Jamaica, 523−550 and 553−576, esp. 568; and Taylor, To Hell with Paradise, 55−67. ↩

-

Further Correspondences Respecting the Constitution of the Legislative Council in Jamaica (London: Houses of Parliament, 1884), link. See also Arthur E. Burt, “The First Instalment of Representative Government in Jamaica, 1884,” Social and Economic Studies 11 (September 1962): 241−259. ↩

-

James Robertson, “Jamaica’s Victorian Architectures, 1834−1907,” Victorian Jamaica, 439−473. ↩

-

Shields, Devon House Families, 26, 28−29. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 30. ↩

-

Prince William’s “profound sorrow” notwithstanding, the British government’s failure to issue an apology suggests that a less cagey admission of culpability would open the UK to liability for financial damages in the immediate wake of having finally finished paying off nearly two centuries of debt to enslavers in 2015. See Danica Kirka, “Prince William Expresses Sorrow for Slavery in Jamaica Visit,” Associated Press (March 24, 2022), link; and David Olusoga, “The Treasury’s Tweet Shows Slavery Is Still Misunderstood,” Guardian (February 12, 2018), link. ↩

-

Shields, Devon House Families, 32. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 78. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 61. ↩

-

For merchants and other small slaveholders—i.e., those not engaged in industrial-scale praedial labor and production—to enslave people in the early nineteenth century was a symbolic practice that conveyed status. What Shane White writes of New York in the early Republic holds true for Kingston at this time as well: “For New York’s elite[,] slaves were not merely an economic commodity but a form of conspicuous display designed to differentiate their owners from other groups in a city they were so radically changing.” Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770−1810 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 46. See also Verene A. Shepherd, “Land, Labour and Social Status: Non-Sugar Producers in Jamaica in Slavery and Freedom,” in Working Slavery, Pricing Freedom: Perspectives from the Caribbean, Africa and the African Diaspora, ed. Verene A. Shepherd (New York: Palgrave, 2002), esp. 157−158. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 101. ↩

-

Gay Nagle Myers, “Refurb Helps Devon House Remain a Kingston Highlight,” Travel Weekly (September 15, 2010), link. ↩

-

See, for example, Louis P. Nelson, Architecture and Empire in Jamaica (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), esp. on Hibbert House in Kingston, 32−35, on the Barrett and Vermont houses in Falmouth, 162−169, and on the “Jamaican Creole House” type, 179−217. ↩

-

In the Caribbean and Latin America, the magnates behind late nineteenth-century infrastructure construction, such as William Henry Aspinwall, Henry Meiggs, and Minor C. Keith, provide relevant analogues. See, for example, Peter Pyne, The Panama Railroad (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021); and Jason M. Colby, The Business of Empire: United Fruit, Race, and U.S. Expansion in Central America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), esp. 19−76. ↩

-

I follow Ferdinand’s definition of the term “racialized” here to refer “to the construction of the racist hierarchy of the West that resulted in many peoples on Earth having the condition of being associated with a race, culminating in the invention of Whites above non-Whites. Because of this asymmetry, I refer to those others, non-Whites, by the term ‘racialized,’ for it is their humanity that has been and is being contested by these racial ontologies, and it is they who de facto suffer a discriminatory essentialization.” Ferdinand cites the philosopher Norman Ajari. Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 3, and 248n5. On Stiebel’s marriage to Magdalen (or Magdalene) Baker and his in-laws, see Rebecca Tortello, “Devon House,” Jamaica Gleaner Special Edition, link; Edmondson, “‘Most Intensely Jamaican,’” 575n43; and Melanie Reffes, “Jamaican Elegance with a Jewish Twist,” Jewish Journal (December 2, 2004), link. ↩

-

Matt Apuzzo, Constant Méheut, Selam Gebrekidan, and Catherine Porter, “How a French Bank Captured Haiti,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Lazaro Gamio, Constant Méheut, Catherine Porter, Selam Gebrekidan, Allison McCann, and Matt Apuzzo, “Haiti’s Lost Billions,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Selam Gebrekidan, Matt Apuzzo, Catherine Porter, and Constant Méheut, “Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The US Obliged,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Constant Méheut, Catherine Porter, Selam Gebrekidan, and Matt Apuzzo, “Demanding Reparations, Ending Up in Exile,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Catherine Porter, Constant Méheut, Matt Apuzzo, and Selam Gebrekidan, “The Root of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Eric Nagourney, “6 Takeaways About Haiti’s Reparations to France,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Catherine Porter, Constant Méheut, Selam Gebrekidan, and Matt Apuzzo, “The Ransom: A Look Under the Hood,” New York Times (May 20, 2022), link; Abrahm Lustgarten, “The Barbados Rebellion,” New York Times Magazine (July 27, 2022), link; Jen Kinney, “The Fight Against Mining in Jamaica’s Rainforest,” Vice News (September 24, 2021), link; “The Fight Against a US Mining Company in Jamaica Continues,” Vice News (April 20, 2022), link. ↩

-

Ferdinand, Decolonial Ecology, 35. ↩

-

Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 27. ↩

Jonah Rowen is an architectural historian whose work focuses on the intersections between architectural technics, materials and commodities, and labor. His research focuses on the design and production of nineteenth-century Anglo-Caribbean colonial exchanges and buildings, figured as technologies of risk management and security.