Saidiya V. Hartman: You have to be exemplary in your goodness, as opposed to…

Frank Wilderson: [laughter] A nigga on the warpath!

—Saidiya V. Hartman and Frank B. Wilderson, “The Position of the Unthought”1

When bass permeates and modulates, it binds bodies together (putting them literally on the same wavelength).

––Paul C. Jasen, Low End Theory: Bass, Bodies, and the Materiality of Sonic Experiences2

I’m a badman, baby I’m Jamaican.

–– Sleepy Hallow, “2 Sauce”3

At a press conference last February, New York mayor and NYPD fanatic Eric Adams suggested banning drill music, linking the “alarming” subgenre to increasing gun violence in the city: “We pulled Trump off Twitter because of what he was spewing,” Adams remarked. “Yet we are allowing music displaying of guns, violence. We’re allowing it to stay on these sites.”4 Days later, after meeting with a coalition of drill rappers, he walked this statement back, instead asking the artists to reduce gun violence in their communities. Adams’s words disguise the structural problems at play and imply that individuals have the power to control the conditions and systemic discrimination they live within. I don’t know who duped whom, or if there was any intention to dupe anyone at all, but as Fivio Foreign explained in response to the possible ban:

“It’s not the music that’s killing people, it’s the music that’s helping n*ggas from the hood get out the hood...This the drill community. I know the police and everybody, they be looking at us like n*ggas is starting trouble. N*ggas ain’t really starting trouble, they tryna feed their kids. They tryna take away drill music off the radio. They tryna stop it from being on the radio.”5

Fivio makes clear how fear of moral alienation leads to criminalization; how fear eclipses the fact that what is often being punished is a relationship to class, race, and governance in a way that makes it easy for all nonnormative behavior to become criminal. Politicians blame the proliferation of violence within a community on that community itself and, in this case, on an entire music genre. The drill community becomes the perfect scapegoat. This reasoning allows politicians to ignore the actual conditions that create and sustain violence and to instead respond with an expansion of criminalization and the carceral state—an expansion of sovereign power. We might, instead, insist on asking: What are the conditions that lead people to use violence as a tool for their potential betterment (at best for their self-defense), and what if those conditions not only remain but escalate?

Even without Mayor Adams, the future of drill music played out in real time on the radio, with DJ Drewski from New York’s Hot97 announcing that he would stop playing diss or gang-affiliated tracks because of the violence. Other radio DJs followed suit. DJ Gabe P and D-Teck from Power 105 agreed that it was their responsibility to pull the tracks off the radio.6 What’s most interesting about these responses is how they make evident a kind of anxiety. DJs are clearly wrestling with their own personal agency—taking responsibility for a massive cultural problem, whose roots, they acknowledge, are in structural inequalities. The visibility of violence in diss tracks has more to do with the status of some current artists, who are historically less commercial, and thus less beholden to label pressures (though they are still, of course, subject to market pressures), and who have not yet necessarily escaped the conditions that define their lifestyles—conditions that necessitate violence. And if the production of diss tracks is a response to the supply and demand of record labels and fans, then the assessment of risk must be questioned. Why are so many artists putting their livelihoods at risk and deciding it’s worth it? What conditions encourage such a risk?

This question becomes especially salient when that risk is actualized as the risk of losing one’s freedom, as lyrics are not only theoretically but legally associated with criminalization. Rap lyrics have been used by prosecutors in criminal investigations and convictions across the country, as seen in the prosecution of Drakeo the Ruler, the current RICO charges against YSL (Young Thug and Gunna's record label), and the successful indictment of now-released New York rapper Bobby Shmurda. This practice has recently been challenged in the “Rap Music on Trial Bill,” passed by the New York State Senate on May 17, 2022. However, the bill does not actually bar prosecutors from using rap lyrics to get convictions. Instead, it limits the use of “creative expression” as evidence, requiring that prosecutors prove that the lyrics are a “literal, factual nexus between the creative expression and the facts of the case.”7 Regardless, the bill sets a precedent tfor scrutinizing the gross attention paid to rap lyrics and the seeking out of criminals in the rap community, calling additional attention to presumptions about the demographics of the people who produce rap music. Months before the bill’s passage, Fivio Foreign responded perfectly to the hypocrisy of putting lyrics on trial, reminding listeners that no one is mad at Denzel Washington for being a bad cop in Training Day: “N*ggas making music, and they feel like that’s the lowest form of entertainment. Why they rich, why they buying these cars, why they got this much?”8 Fivio’s comments mock the racist, capitalist anxiety about rappers getting rich, having more than people want them to, escaping the conditions they’re subject to, and, in that escape, not assimilating or performing respectability politics.

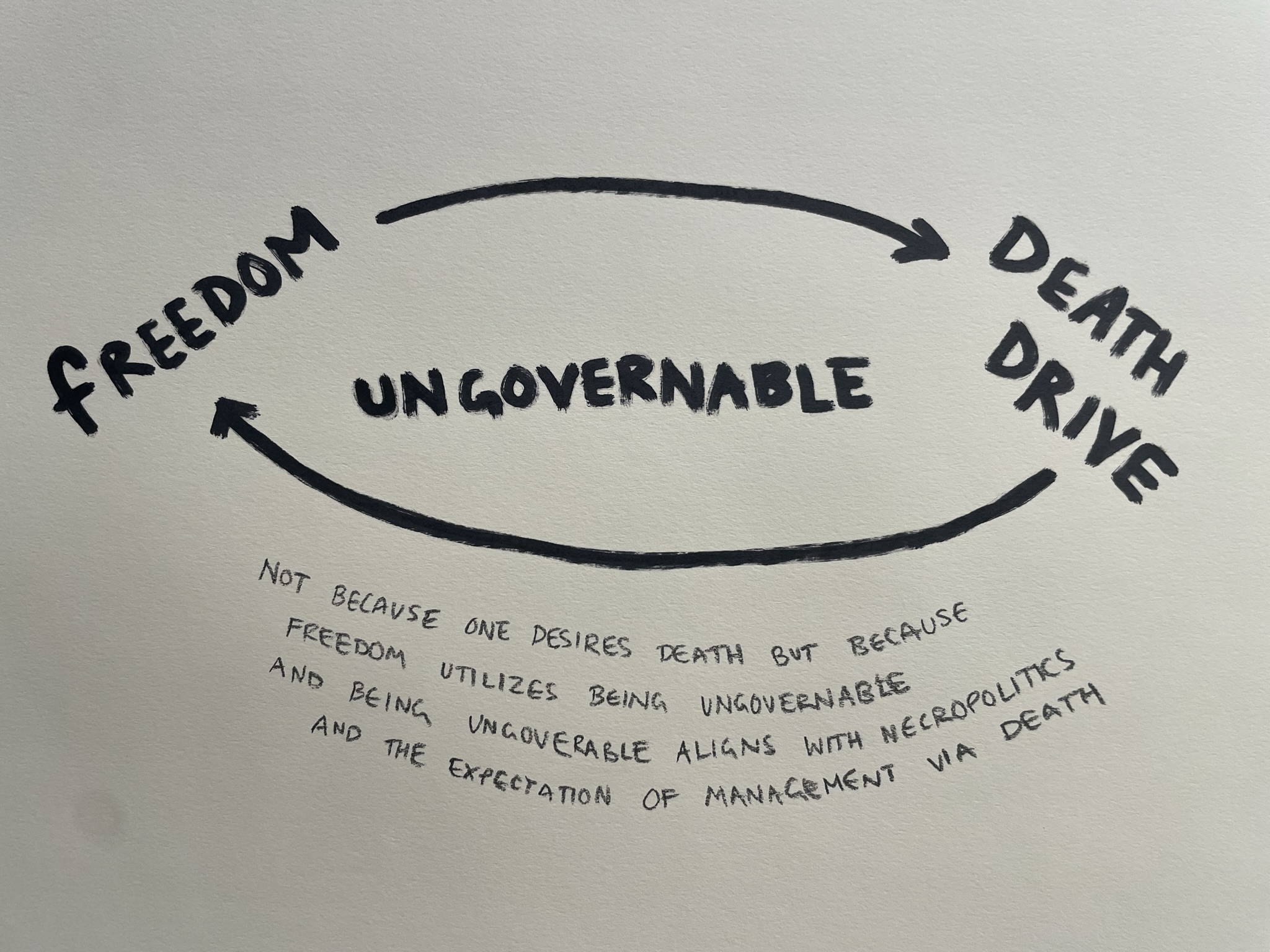

To be respectable is to be governable. Respectability is a means of enforcing the violence of normalcy. Liberalism and racism have become naturalized in globalization. Foundational to liberalism is a paradoxical relationship to freedom. The production of freedom establishes the cost of freedom: governance, control, and means of coercion. Freedom and autonomy (as individual sovereignty) are historically imagined as universal to humans via reason—that there is reason, some inherent morality uniting all humans, and that this reason is why humans have autonomy. This rhetorically disguises the actual cost of freedom and enforces the comforts of universalism, a rhetorical equality. To be ungovernable, or to be bad, poses a threat to the reproduction of normativity, the reproduction of a civil society that maintains the rhetoric of reason and universalism to maintain sovereign power, sovereign power being the power of life-giving and death dealing, the power of control and regulation as it relates not only to individuals but to certain populations and their governability or ungovernability.9

Introducing Badness: A Who Bad?

Jamaican political scientist Obika Gray identifies badness-honour as a form of “dramaturgy” performed by disadvantaged groups, which employs “intimidation and norm-disrupting histrionics to affirm their right to an honour contested or denied.”10 Within the drill community, a certain attitude and way of moving, which might be referred to as demon time, is validated as a social norm. A deviance toward civil society is performed while, simultaneously, explicit remarks are made about the desire to exist within better circumstances (usually financial ones). What New York calls demon time and what the Anglo-Caribbean calls badness are regional but parallel conversations on governability. The potential and problematics of both terms arise from their function as systems of morally coded gestures and vocabularies that create a shared understanding about the respective communities’ basis of identity and their terms of power.11

The violence implicated or enacted in badness is “not through the violent machinery of the state [maintenance of state sovereignty], but through the aggressive display of unpredictable and ominous corporeal power.”12 This is what makes the dramaturgy of badness-honour so important: it taps into the generative theatrics of violence while interrupting the state’s monopoly on violence. The desire to censor music from social media and the radio because of its ability to proliferate makes it evident that “unpredictable and ominous corporeal power” is not the only thing that threatens state sovereignty. Noncorporeal performances of badness (ungovernability) threaten the state’s monopoly on violence, not by competing with the state but by disregarding the effectiveness of the state’s use of looming violence as a means of control, regulation, and maintenance of power. Badness as a subaltern affect is fundamentally about its ability to attract attention.13 Gray would argue that this attention is a means of affirming respect or humanity where it is denied. But it is not about affirmation as much as it is about negation, challenging the ways in which respect, honor, and humanity are imagined and given. The social potential of an affect is what makes badness available to the masses as a means of negotiating one’s status, rights, and material desires.

Badness has many outlets as an affect. Chop dancehall, a genre defined by its narrative connection to scamming (specifically phone lotto scams), has come to express or summon obeah, a set of creolized spiritual beliefs and medicinal practices brought to Jamaica by West African slaves. It was first outlawed in 1760 in the aftermath of Tacky’s Revolt, one of the largest slave uprisings in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic, as a way to prevent future rebellions.14 Obeah was thought to organize and embolden the enslaved, offering protection from harm, and was thus considered both a threat to white cultural hegemony and a form of immunity to the threat of corporeal violence. Even after the end of slavery in Jamaica, obeah was made illegal in 1834 under the Vagrancy Act and then more specifically in the Obeah Act of 1854 and 1898.15 While no one has been convicted of obeah in decades, it has not yet been decriminalized in Jamaica and still carries negative (even hostile) cultural connotations (especially given the dominance of Christianity throughout the country).16 The public degradation and forced secrecy of obeah aligns itself with chop dancehall, where it is both used and showcased, adopted by the name guzu. This is seen from “Yahoo Boyz,” depicting deejay Intence sacrificing a chicken and dripping the blood across his ring before sitting inside a circle of candles to chop the line, to Slyngaz’ lyrically and visually detailed song “Obeah Man.”17 Obeah practices become highlighted in the vernacular of badness, with almost any current chop song mentioning ritual sacrifice and/or guard rings. Deviance finds its necessary tools, and out of those tools arise a communal language, history, and set of practices.

Chop dancehall finds itself hyper-visible in Jamaica for fueling financial scams just as drill has been over-associated and blamed for gun violence in New York City. Neither of these things is true—neither of these genres is responsible for forms of extractive violence and yet the visibility of their dramatics draws attention to them, allowing critics to name them as the real problem. This is, in part, what they desire; the attention they are given is twofold. On the one hand, it expresses the anxiety and strain that their public performances of badness put on respectability, their defiant branding uses their negated positions in civil society to express themselves, create sociality and a product for their financial betterment. On the other hand, the attention leads to constant attempts at control: extreme surveillance, criminalization, death, and scapegoating. Again, there’s a slippage between who’s duping who. It’s a double bind: the potential escape route is one that simultaneously puts a person at exponential risk.

While badness’s theorization originates in the struggles of disadvantaged people, it is not exclusive to them. Badness occurs across different political systems and is available to anyone entangled in societal power relations. Scammers come from all class backgrounds in the same ways that violence is committed by people of all positionalities. Privilege is the invisibility of whiteness (always) and the upper class’s relationship to criminality. This is most visible in the currently unfolding case of Usain Bolt having been defrauded of over $12 million by a private investment firm in Jamaica. The accused perpetrators are employees of the firm SSL, which clearly doesn’t have to chop the line to get some money.18 Violence, coercion, lies—all those things associated with criminality—are always already owned and performed by the state and upper class, because that is how they maintain control. Yet badness, as this essay is interested in it, also appropriates, and disrupts, the hegemonic uses of these tools.

For Gray, badness’s means of dissent by the globally disenfranchised arise in contexts “where the exercise of power is harsh, pre-emptive and ubiquitous, yet not so totally monopolistic that popular defiance becomes impossible.” 19 Badness’s ability to be disruptive is based on treating the threat of state violence with a degree of indifference, indifference by way of acculturation. The state does not need a denizen to transgress to be violent. State violence is continuous: It is a form of maintenance based on the belief that the propensity of its denizens (for violence) is justification enough. But it also emerges out of a combination of other conditions: in societies where the desire for upward mobility through individualism is “intensely shared”; where the “mobilized poor is actively impugned”; where “material wants [are] stubbornly denied”; where the poor are mobilized for political agendas and also “simultaneously throttle[d]—by [state] violence and cooptation”; where the “urban poor are alienated and highly-mobilized around issues of ethnic discrimination.”20 Mobility—controlled or denied or organized or inspired—is central to the production of badness. Badness thus contests the limitations put on social, economic, and cultural mobility. And the potential of badness also lies in its relationship to mobility: its ability to spread, to move, to create a sociality that evades and combats the means of control. This same use of mobility is mirrored in notions of diaspora—people who are connected despite national borders and whose cultures are conversationally produced across national lines. I refer here specifically to the Black diaspora as a product of the transatlantic slave trade and the Jamaican diaspora as a product of contemporary transnational migration. Ironically, both diasporas’ movements of origin were forced, one by the extractive practice of chattel slavery and the other through extractive colonialism and, later, imperialism. Deborah A. Thomas, a Jamaican American anthropologist, suggests that diaspora might be traced through state structures or epistemologies of violence, a construct that allows us to understand political and cultural communities outside of nationalist frameworks while still keeping in frame the reality of state and transnational imperialism.21

Diaspora: A Very Sticky Web

Black communities in the diaspora are created through systems of cultural exchange. In this exchange, intersubjectivity is created via the reproduction of sociality. Paul Gilroy calls this system of relation “diasporic resources.” Diasporic resources are the raw materials of the diaspora. Music, aesthetics, iconography, religion: these are the things that people draw on to create and re-create their own cultures and communities. Drill and dancehall exemplify performances of badness (ungovernability) to be circulated, consumed, reproduced, responded to, and syncretized. As diasporic resources, they are also reactions to—and therefore bear traces of—the hegemony of globalized liberalism and transnational imperialism. Since sovereign power relies on cultural hegemony, it is threatened by diaspora, which through the mobility of people and culture produces alternatives to dominant cultures and subverts the singularity of globalization. Gilroy calls attention to the ways in which Blackness, as a diasporic identity, is embodied, a sense of self that comes through practiced activities of sharing:

Black identity is not simply a social and political category to be used or abandoned according to the extent to which the rhetoric that supports and legitimizes it is persuasive or institutionally powerful… It is a lived coherent (if not always stable) experiential sense of self. Though it is often felt to be natural and spontaneous, it remains the outcome of practical activity: language, gesture, bodily signification, and desires.22

This theorization of Black identity is especially grounded in moments where sharing resources has clear material consequences. With chopping, specifically, badness can be seen evading national economic structures. Skillibeng’s “Brick Pan Brick,” released in 2019, samples a news segment that declares, “The US trade federation says, Jamaican scammers are still calling unsuspecting people in the US, claiming they’ve won millions, but of course then asking them to send a fee to release the winnings.”23 This scam has brought in an estimated USD 1 billion annually, though it is largely unaccounted for due to its illegality.24 This US–Jamaica relation is traced in “Chappa Gyal” by Honey Milan (a Jamaican-born artist raised in Oklahoma) and Skillibeng. The song and video unfold a phone call and money exchange as Honey Milan sings, “Mi spend the cash, mi nah have no remorse, dem send it to me, neva tek it by force.” She continues, describing how she then spent some of the money: “Last week mi ship a barrel full of Air Force, send down a couple iphone of course.”25 While the means of obtaining money is an illegal phone scam, the scamming is downplayed by that money then recirculating through the legal economy via the tradition of shipping barrels.

Jamaica has a nearly one-to-one ratio of nationals to diaspora members.26 Its diaspora contributes billions of dollars to Jamaica annually through remittances, more than USD 3 billion in 2021,27 more than one-fifth of Jamaica’s GDP. The practice of going to work in economies with higher-valued currencies to send their dollars and pounds back to Jamaica dates back decades, preceding independence. In this way, the Jamaican economy has always exceeded national boundaries. It’s important to note that these legal economies also mirror illegal ones. The transnational circulation of money already occurring via the Jamaican diaspora’s remittances validates the exchange route of money via scams that target people in the United States. Scamming thus becomes not a singular event but part of an everyday crisis that has been historically unfolding despite current experiences of it. Money, like other diasporic resources, necessitates looking at the “diaspora as a process rather than a historical event or state of being”28 and at migration as bidirectional rather than unidirectional.

In the music video for “Gang Bang,” dancehall artist Skeng is first seen wearing iconic New York apparel. Despite being in filmed in Guyana, he has on a Yankees fitted and a matching jersey.29 Later, Skeng wears a Mets fitted and jersey as he stands in front of a commemorative mural honoring King of New York and deceased drill rapper Pop Smoke in Canarsie, Brooklyn.30 The reference to Pop Smoke is not momentary. Skeng spends almost a third of the video in front of this mural or in relation to it. This Pop Smoke reference feels deeply self-aware, not just of the diaspora (as Pop Smoke was born to a Jamaican mother and Panamanian father) but also of the transnational parallels between Skeng and Pop Smoke’s regional gunman tunes. Pop Smoke has a line in which he cites duppies, an Anglo-Caribbean (largely Jamaican) word for ghost or spirit. In “Meet the Woo,” he raps, “I turn that boy to a duppy”; it’s not just his use of duppy but moreover his use of it in relation to killing someone. Although still a noun, it functions similarly to a verb, with the implication of an action.31 This practice is popular with Jamaican dancehall artist Masika, who sings, “Money and duppy we make most," and Skeng, singing, “Anything weh pass dem place get duppy up” and “everyday new duppy drop.”32 Diasporic resources create a spiderweb of relations, of spatial, psychic, and temporal connections that link but don’t erase distinctions between participating communities and cultures.

The distribution of diasporic resources is accelerated by media networks, especially music, and its increasing digitization produces something that travels, mostly fluidly, across boundaries with no passport, no visa. New York drill and choppa/gunman dancehall are of particular interest as diasporic resources because they center themselves around performances of badness (ungovernableness) and thus epitomize an intersubjectivity that disrupts civil society and awakens its anxieties. Even dancehall and drill’s means of dispersion play on an avoidance of governability or control, as YouTube is the unofficial official release platform for both genres. YouTube has been the preferred release platform in dancehall for a minute, but it’s become increasingly useful as sample drill pops off in New York, as those samples aren’t getting cleared for streaming services or mainstream production.33 This decentralized form of dissemination is important in how it utilizes digital space to speed up the call-and-response production of diasporic resources. Artists across the diaspora can enter the conversation in synchrony.

In an interview with On the Radar Radio about his “Whap Whap” remix, Skillibeng is told that he looks comfortable in New York. He replies, “Yeah, I’m good, it’s New York, what do you mean? Yeah, it’s my city, it’s like my hometown, cause my mom lives in New York since I’ve been a kid.”34 He clarifies that this is his first time being in the United States, but for him that doesn’t conflict with what he just said. It is one thing to argue about the Jamaican-ness of New York, but how accessible Jamaica can feel in New York is undeniable—if in the right neighborhood, one could speak patois forever. Diaspora is always crossing boundary lines, straddling them, occupying multiple places simultaneously. Movement is the foundation of diaspora, but understanding the limitations of national borders, that Jamaicans need visas to visit the United States, means that ideas of mobility must be contested and stretched. The origin of diaspora is the movement of people, but the totality of a person is never just the location of their body; aesthetics, language, money, material goods move as well. The sum of these movements coproduces culture. And while kinship is cultural, diaspora is not inherently kinship. Kinship requires a greater depth, or more specificity to what is shared (values, goals, responsibilities).

Another of Skeng’s recent music videos takes place largely in the Bronx, home to a sizable Jamaican and Afro-Caribbean diaspora. The video for “Protocol” begins with Skeng and his homies in Wakefield, a neighborhood with a historically large Jamaican population. It is identified by a very pointed shot of the cross streets of 223rd Street and White Plains Road.35 While several scenes in the video actually do take place in Jamaica, even when you’re there, there is a wall of cinderblocks with “BRONX” graffitied across it. Once again, considering the speed and transnational distance that these genres and their videos circulate, the community of people engaging with these resources develop and share aesthetic signifiers. In the same music video, a man in Jamaica wears a shiesty, which, unlike regular ski masks, only has one hole. Popularized by Memphis rapper Pooh Shiesty, these masks are now simply referred to as “shiestys,” and corner stores in New York have even started donning signs that say “no shiestys.”36 Signs like these (both the mask and Bronx graffiti) are unifying and relational. There are practical (legal) reasons for wearing a mask to hide one’s individuality and, within that reasoning, the refusal of singularity creates a universal badman, an exchangeable badman, a fungible badman—illuminating the tensions between multiple places, a disassociation with the national, a multidirectional denizen status.

Is Badness Contagious?

In June 2022, Skeng was banned from performing publicly in Guyana by the country’s minister of home affairs, Robeson Benn, after gunshots were fired into the air during a live performance of “Protocol.” The rhetoric of “performing publicly” is critical because it dictates the specificity of the problem. Justifying the ban, Benn states, “If they want, they can go into a private club and behave as badly as they want. But we will not sign off on any such artist or any artist who has a record of promoting vulgar and lawless behaviour including the firing of gunshots in public places. We reject it completely.”37 It should be noted that Skeng and his people were not the ones responsible for the gunplay; someone in the Guyanese audience was. What this indicates is that the gunplay itself isn’t the problem. It’s the influence that badness has on the public, the potential contagiousness of badness that needs to be contained. Benn explicitly states that “No artist like Skeng will ever come into this country.”38 The use of like highlights the fungibility of Skeng as an artist, but more importantly as a social marker. Skeng himself is not a threat, he is symbolic of one, the universal badman. Benn even hinted at his intentions of removing Skeng’s music from the radio in Guyana, echoing the threats made toward drill by New York mayor Eric Adams.39

Dancehall Mag makes a point to note that Skeng is not the first Jamaican dancehall deejay to be banned from Guyana. He joined the likes of Movado in 2008 and Vybz Kartel in 2011. After he was banned from Guyana in 2011, Vybz Kartel said, “I refused to go there before the ban was imposed so that ban wasn’t necessary. I banned myself. Big up the Guyanese Gaza fans but I would sooner tour Iraq than go to Guyana.”40 But Kartel doesn’t seek out any type of vindication, appeal, or apology; someone said, “fuck you,” so he said, “fuck you too,” no questions asked. Saying that he would sooner tour Iraq than Guyana is intentional. The United States was at war with Iraq at the time—therefore his comment was not only of solidarity, not only a “fuck you” to the Guyanese government, but also a “fuck you” to the imperial powers at war.

The fear of public performance directly relates to influence. Gray notes that

as state agents and sympathetic elites in these places increasingly accommodate the moral values of alienated subcultures, allegiance to traditional civic norms may be eroded even more. Badness-honour is likely, therefore, to be invigorated when sympathetic elites and parties lend their legitimacy to this repertoire of power. Such elite groups do so by championing popular grievances and mimicking the norms of aggrieved and stigmatized groups. In these contexts, cultural counter-penetration from below by influential subcultures may in time subvert civic norms and values.41

This does not come to fruition. Instead, when badness is not repressed, it is often hypocritically and capitalistically co-opted. This is demonstrated by Jamaica’s prime minister Andrew Holness as he responds to Skeng being banned from public performances in Guyana: “When another country says ‘I don’t want your artistes in my country,’ it’s an embarrassment.”42 He continues: “Whap Whap and Chop Chop and Ensure and all of them… all of those things have their place but they can’t define us. We should not allow that to define us.”43 The irony about them having their place is highlighted by the fact that Holness used these same deejays to make dubplates for his 2020 political campaign.44 So, what is the correct place for these songs to hold? Private space? Political campaigns? Public space when you want to appeal to the “people” but not on their terms?

Please Be Good? For Me? For Us?

God forbid that the exploitative structures of the state that create the reality from which drill and dancehall emerge are the problem. Instead, it’s the dissemination of badness that somehow begets the conditions that produce it. This is intentional. Policing this genre is not about public safety; it’s a matter of social control. The anxiety around what Gray calls “an erosion of civic norms” is actually the unveiling of the state’s and elites’ hypocrisy, in which the civil norms of crime and punishment are found to be falsely constructed, falsely applied, and therefore illegitimate. That would then call into question both those in power and the power they enact as illegitimate. Since the elites and the state are never criminals in their own eyes, even when committing what they themselves define as crime, the democratization of badness is more likely than the democratization of criminalization. But when it is made public that these deviant behaviors are practiced by all classes, the rhetorical moral divide fails. The falsely constructed moral hierarchy between “criminals” and the elite/state as rightful punisher collapses. The image and rhetoric of moral difference obscures reality and this obstruction is necessary for maintaining the sovereign powers of the state. As badness is continually repressed in exclusively one group of people, it simultaneously intensifies the social conflict between the subaltern and the dominant class that produces badness as a means to begin with.

What we find is that Black people are not exempt from positions within the elite, the state, or in defense of civil society. The system of racialized labor, via the transatlantic slave trade, that created a shared experience and the dominant basis for the Black diaspora also created Blackness as an antagonism to civil society, an antagonism to potentially be vindicated. Black nationalism became a nationalist movement that transcended the actual nation-state, identifying its nation as one without physical borders, instead composed by notions of racial belonging. Like other nationalisms, it has a political function, and its political reasoning is vindication. Racial vindication is the argument that Black people are equal to white people in their qualities, abilities, and humanity. It arrives as a response to racial identification becoming institutionalized, as racialized labor became the basis for global capitalist economic production. Historically, it was used to create cultural self-esteem against colonial/imperial epistemologies about Black people.45 The political project of unmaking these tropes validates the autonomy of Black people, but it doesn’t change their position as antagonistic to civil society. That type of vindication would require the destruction of civil society. The destruction of civil society is why badness or ungovernability as a diasporic resource to build intersubjectivity is extremely necessary. Deborah Thomas notes that racial vindication operates in both the United States and Jamaica, though differently, utilizing diasporic resources.46 I argue that racial vindication projects in both the United States and Jamaica are united and co-opted by their relationship to respectability and governability.

Looking at shifts in the rhetoric and policy of American civil rights organizations, Jackie Wang suggests that the abandonment of poor and criminal Black people by said rhetoric and policy stems from a fear of “affirming the conflation of blackness and criminality.”47 Again, this shift is not only present in the history of the American civil rights movement, as it is demonstrated globally in Black communities. And it’s extremely present, not only as a fear of Blackness and its potential relation to criminality but also as a fear of Blackness and its historical relation to class. These rhetorical distinctions make it so that Black people who can be associated with criminality, or who openly associate themselves with criminality, must be alienated or removed from society. This produces a group of people to serve as collateral for the racial vindication of an exceptional Black class, those striving for economic and social mobility as granted by civil society.

In the face of these racial vindication projects that maintain their basis in respectability and distance from criminality, the nuances of badness illuminate the ways in which people desire delusions of sovereignty as something historically outlined and morally defined. It is difficult to detach from life-building modalities that no longer do just that—life-build—but instead create obstacles to life. The practice of badness is not as spectacular as its affiliation with the music industry would have it seem; its dramaturgy is more exchangeable as a diasporic resource in music networks, but badness precedes these performances. It is a more ubiquitous tool, an affect, an action, an affinity. Revolutionary violence is often talked about as needing political or sovereignty-oriented intention, but the everyday presence of an affect is not the absence of revolutionary potential simply because it is reactive, not premeditated in its striving toward revolution. Transnational badness ignites a slippery interest in suspending the reproduction of normative life, and of hegemonic globalization.

-

Saidiya V. Hartman and Frank B. Wilderson, “The Position of the Unthought,” Qui Parle 13, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 2003): 189. ↩

-

Paul C. Jasen, Low End Theory: Bass, Bodies, and the Materiality of Sonic Experiences, (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016), 22. ↩

-

Sleepy Hallow, "2 Sauce," YouTube video, March 24, 2021, link. ↩

-

The Recount, Twitter post, February 11, 2022, 1:21 p.m., link. ↩

-

TMZ, “Fivio Foreign Talks Importance of Drill Music,” YouTube video, 1:45, February 8, 2022, link. ↩

-

Andre Gee, “Why Violent Diss Songs Are Getting Pulled from New York Radio,” Complex, February 10, 2022, link. ↩

-

Brad Hoylman-Sigal, “Senators Brad Hoylman & Jamaal Bailey Introduce ‘Rap Music on Trial’ Legislation to Prevent Song Lyrics from Being Used as Evidence in Criminal Cases,” New York Senate, November 17, 2021, link. ↩

-

TMZ, “Fivio Foreign Talks Importance of Drill Music.” ↩

-

Lauren Berlant, “Slow Death (Obesity, Sovereignty, Lateral Agency),” in Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 95–121. ↩

-

Obika Gray, “Badness-Honour and the Invigorated Authority of the Urban Poor,” in Demeaned but Empowered: The Social Power of the Urban Poor in Jamaica (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2004), 129. ↩

-

Gray, “Badness-Honour,” 129. ↩

-

Gray, “Badness-Honour,” 130. ↩

-

My use of affect is by way of “affect theory” to organize emotions and subjectively experienced feelings into social and interconnected networks. ↩

-

On Tacky's Revolt, see "Takcy's War," Wikipedia, December 11, 2022, link. ↩

-

The Obeah Law, 1898, CO 139/108, National Archives, UK, link. ↩

-

Talk of repealing the Obeah Act in 2019 was met with resistance from many Jamaicans—pointing to not only the complicated and contested meaning of the word but also the complicated and contested relationship to colonialization. See link. ↩

-

Intence, "Yahoo Boyz," YouTube video, 0:00-0:15, July 5, 2021, link; Slyngaz "Obeah Man," YouTube video, February 28, 2022, link. ↩

-

On Usain Bolt's case, see Jovan Johnson, "Millions missing from Usain Bolt's account at investment firm SSL," Jamaica Gleaner, January 12, 2023, link. ↩

-

Gray, “Badness-Honour,” 132. ↩

-

Gray, “Badness-Honour,” 131–132. ↩

-

Deborah A. Thomas, “The Violence of Diaspora: Governability, Class Culture, and Circulations,” Radical History Review 103 (2009): 83–104. ↩

-

Paul Gilroy, “Jewels Brought from Bondage: Black Music and the Politics of Authenticity,” in The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (New York: Verso, 1993), 102. ↩

-

Skillibeng Official, “Skillibeng—Brik Pan Brick [Official Music Video],” YouTube video, 3:55, December 7, 2019, link. ↩

-

“US$1 billion Flowing into Jamaica from Lotto Scam, Drugs, Money Laundering, Annually,” Jamaica Gleaner, June 1, 2022, link. ↩

-

Skillibeng Official, “Honey Milan, Skillibeng—Chappa Gyal [Official Music Video],” YouTube video, 3:43, May 13, 2021, link. Most chop songs involve Jamaicans scamming Americans. This is not to say that Jamaicans do not also scam other Jamaicans. ↩

-

Caribbean Policy Research Institute, “Economic Value of the Jamaican Diaspora,” May 2017, link. ↩

-

Chanel Spence, “Remittances Exceed $3.3 Billion in 2021,” Jamaica Information Service, April 5, 2022, link. ↩

-

Deborah A. Thomas, “Blackness Across Borders: Jamaican Diaspora and New Politics of Citizenship,” Identities 14, no. 1–2 (2007): 111–133. ↩

-

Skeng, "Gang Bang," YouTube video, 0:57-1:05, June 9, 2022, link. ↩

-

R.I.P. ↩

-

Pop Smoke, "Meet the Woo," YouTube video, April 16, 2019, link. ↩

-

Popcaan (feat. Masika and Tommy Lee), "Unda Dirt," YouTube video, December 11, 2020, link; Navaz ft Skeng, "Pop Molly," YouTube video, December 17, 2021, link. ↩

-

While YouTube is not a utopic platform and copyright laws can still be enforced, it offers a slippery space. There is no distributor necessary to upload music to the platform, only an account and an email address. The enforcement of copyright laws is already filled with loopholes that can be exploited, the visibility of a song or artist is one of them. Before an artist or song blows up, there is a moment of limited visibility where they can operate on the edges of legality because their product is assumed to have no traction, influence, and financial stakes (yet). Once attention is received and an economy opens for that product, governance and legality follow. ↩

-

On the Radar Radio, “Skillibeng on Nicki Minaj, Vybz Kartel, ‘Whap Whap’ Remix w/ Fivio Foreign, New Music with Wizkid,” YouTube video, 27:07, July 14, 2022, link. ↩

-

Skeng x Sparta, "Protocol," YouTube video, November 12, 2021,link ↩

-

Pooh Shiesty (feat. Lil Durk), "Back In Blood," YouTube video, January 2, 2021, link. ↩

-

Dani Mallick, “Skeng and Many Dancehall Artists Are Now Banned in Guyana, Says Minister,” Dancehall Mag, June 10, 2022, link. ↩

-

Mallick, “Skeng and Many Dancehall Artist Are Now Banned In Guyana, Says Minister.” ↩

-

Mallick, “Skeng and Many Dancehall Artist Are Now Banned In Guyana, Says Minister.” ↩

-

Krista Henry, “Following Ban, Kartel Says… I Won’t Be Visiting Guyana Ever,” Jamaica STAR, September 22, 2011, link. ↩

-

Obika Gray, “Badness-Honour,” 134. ↩

-

Andre Williams, “Whap Whap, Chop Chop and Ensure Negatively Impacting Youth, Says PM,” Jamaica Gleaner, June 13, 2022, link. ↩

-

Williams, “Whap Whap, Chop Chop.” ↩

-

Andrew Holness, Twitter post, August 15, 2022, 3:01 p.m., link. Duplates for Holness' 2020 political campaign. ↩

-

Deborah A. Thomas, “Racial Situation: Nationalist Vindication and Radical Deconstructionism,” Cultural Anthropology 28, no. 3 (2013): 519–526. ↩

-

Thomas, “Blackness Across Borders: Jamaican Diaspora and New Politics of Citizenship.” ↩

-

Jackie Wang, “Against Innocence: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Safety,” in Carceral Capitalism (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2018), 260–296. ↩

Shani Strand b. 1995, New York, NY, raised Teaneck, NJ. They have shown at Rachel Uffner, New York (2022), HOUSING, New York (2020), SPACES, Cleveland (2017). They have held residencies at Automata, Los Angeles (2022) and Interstate Projects, Brooklyn (2018). They have been published by Pin-Up Magazine (2021) and lectured at Harvard Graduate School of Design (2022). They hold a BFA and BA from Oberlin College and are currently an MFA Sculpture candidate at UCLA.