On the outskirts of a small city in Belgium, a meager 1.5 kilometers from its center, I am touring a mountain in the making. Hidden behind a treeline, green wire, plastic fences, and what appears to be a wall of stacked soil, an outsider would be surprised to find a fully operational landfill.1 From the ground, the landfill’s size is impossible to grasp. Only when one continues the tour virtually, from Google Earth, do its depth and scale become impressive: an inverted topography partly covered with a creased black layer whose veins reflect the sun, glittering as they were captured by a satellite’s camera. Viewed from 200 meters above, it is at first unclear how to read sites such as these: those collectively categorized as “operational landscapes.”2 In today’s highly coordinated industrial economy, this odd term describes any active industrial site, typically situated on the periphery that, in one way or another, fuels the activities of the center.

The idea of operational landscapes is illustrated in Italo Calvino’s fable Invisible Cities, where citizens have become detached from the realities that enable them to flourish. Behind their city walls, people are effectively shielded from the aftermath of extraction and discarding.3 After all, “Dirt can only go to places that are on the outside”4—what I term the “geospatial other”—a sacrificial zone destined to receive the aftermath of an accelerated growth paradigm globally.5 Yet physical distancing alone would not establish such a pervasive center-periphery binary able to extend overseas and beyond.6 It required language too. No community sets out to explicitly produce waste or prevent reuse. Rather, as anthropologist Robert Ascher notes, people want to be “morally and physically detached from its further existence.”7 It is no coincidence that the banal term “Throwaway” was featured on the cover of Life magazine (August 1955) as this idea crept into the community fabric of postwar societies in the US and overseas.8 This language represented and fostered acceptance of both the practice of wasting and waste’s magical disappearance.9 Just as Calvino’s fictional characters must ultimately come to terms with the consequences of imagined distance, many of us have realized that the idea of “Away” never held true. Yet, contemporary waste management in many countries perpetuates the illusion by upholding a clean and safe center.10 Throwing Away has turned from a fleeting adverb to an implacable noun: both narrative and tangible destination.

Given this uneasy, detached relationship with landfills, it makes sense that I was only able to find one such as the Flemish Mountain via Google Earth. Without satellite imagery and sea-level projections, I would not have known that the highest point of my Dutch province is a closed landfill near Nuenen called Landgoed Gulbergen. Smoothed out from above, with curvy narrow paths winding their way around and downward, Gulbergen could be the large-scale work of a land artist. Yet in flatland Netherlands, the unusual topography rising 60 meters arouses suspicion when viewed from near or far.11

Landfills have typically been airbrushed away in this manner: erased from collective memory under urban sprawl until a crisis surfaces them. On September 15, 1979, in Lekkerkerk, a small Dutch city near Rotterdam, “an enormous fountain sprouted meters high and lifted the pavement” near a newly built housing estate. The main drinking-water pipeline had not only burst but was found “black and… blistered.”12 Unbeknownst to the residents, they had been living above a former landfill holding household refuse and barrels of chemical waste that had been dumped there illegally by container company Wijnstekers in 1971.13 The toxic contents had eaten into the water networks. Three hundred residents were evacuated in the wake of the incident, and only a few returned after a yearlong excavation and remediation effort.14 Back then, landfills were not equipped with barrier systems to avoid contamination from plastics and metals—known as solid wastes—or from liquid chemicals and inorganic matter that were a steadily growing share of the waste stream, and ultimately of the landfill.15 As organic matter decomposes and mixes with new inorganic matter, a brown tealike liquid known as leachate forms.16 At the time, this novel toxic liquid’s risk to municipal water networks and groundwater supply was underestimated. Sites typically lacked monitoring and retention systems for the potent greenhouse gas methane, which is prone to building up within the landfill and sparking fires when released.17 Though devastating, the widely publicized incident at Lekkerkerk highlighted the urgent need for the Dutch Soil Protection Act and drove its passage.18

Searching for the Mountains

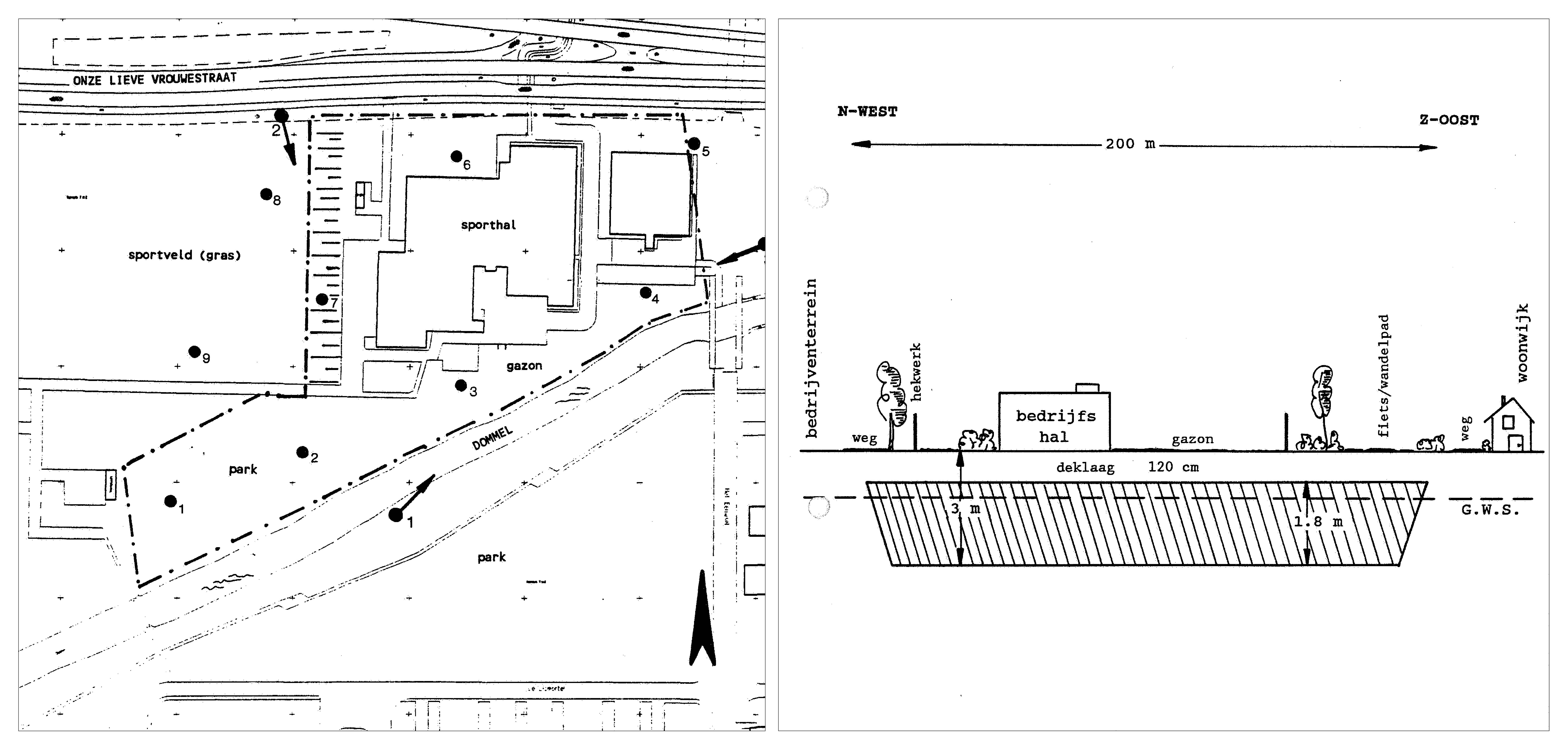

Standing on the 60-meter peak of Landgoed Gulbergen, I wonder where other landfills had been created in the Netherlands. As it turns out, I was not the only one searching. Thirty years earlier, it was crucial to locate Away not only to avoid unexpected breakdowns such as Lekkerkerk but to establish whether any of these sacrificed zones could be remediated and thereby redeveloped. Space is scarce, as the Dutch know too well.19 From 1995 to 2004, the Netherlands ran a program called NAVOS to take stock of former landfills, including sampling soil and groundwater.20 The task was not straightforward. Without prior monitoring and containment, local people and administrations had to be consulted on their knowledge of the sites, their size, and their possible contents.21 When the surveyors were finished, about 6,000 sites had been counted across all twelve Dutch provinces.22 Risks were assessed, precautions taken, and heaps of soil added.23

Shortly after the start of NAVOS—and as formerly Communist states sought to enter the European Union in the mid-1990s—the proliferation of potentially dangerous landfills could no longer be overlooked. What followed were years of negotiations among EU council members to agree on a Waste Directive. At last, a date was set. From September 1, 1996, “only safe and controlled landfill activities should be carried out throughout the Community.”24 All active landfills had to comply with new sanitary measures. Sites that had already been filled and closed were distinguished as “former” landfills, and these were to be monitored for their potential harm and remediated only if necessary.25 The directive, designed to decrease the total number of landfills, would become a decade-long struggle among member states.26 Despite these efforts, the known number of landfills, both closed and active, in the European Union is equal to approximately 300,000 hectares—the size of Luxembourg.27 With many EU countries still predominantly relying on landfills as the first and last node of Away, the Union’s target for only 10 percent of municipal waste to end up in landfills by 2035 appears far from reach.28

Today’s citizens and particularly future generations might acclimatize quickly to former landfills in the Netherlands and many other EU countries. This all-too-easy adaption, however, concerns ecologists, who coined the term “shifting baseline syndrome”29 to emphasize the consequences of the psychological normalization of degraded territories. Unlike an open coal mine, however, the closed and nature-padded landfill is not an obvious ruin. Instead, underground landfills may vanish beneath “green spaces” in the city center, their memory replaced by a flurry of housing and industrial sites as well as golf courses and solar parks, as is often the case in the Netherlands. There, Landgoed Gulbergen and the VAM waste mountain in Drenthe have become destinations for mountain biking.30 Future generations may forget the seemingly antiquated waste disposal just beneath their feet, and along with it the still-operational landfills in their country. As citizens move on from these contested postnatural landscapes, it further enshrines the alleged mastery of waste streams—including that of recycling as a viable solution31—all of which, ultimately, constitutes and upholds the idea of Away.32

Inside Away

Back at the operational Flemish Mountain, I can see how the surrounding communities are already shielded from these ongoing material histories. Fencing the site is necessary, not only for the sake of Away but as a matter of public safety. On this day in late July, the sales manager himself is giving the tour even though I am not a prospective customer but a designer-turned-researcher. I can sense that he is wary of my interest in his line of work. Still, I receive a company-branded high-visibility jacket: the temporary entry ticket to this demarcated sacrifice zone. Once inside, I am looking down into the inverted topography of a mountain, a void fully lined with layers upon layers of black plastic sheets reflecting the bright summer sun. They are weighted down with yellow company-branded sandbags on rising terraces, objects I recognize as the yellow dots visible in satellite imagery. The scenery evokes an ancient arena. Behind us, I spot a sprinkler peacefully pumping and spraying water. From afar, it could be mistaken for any other garden activity, but here it is keeping asbestos dust from spreading—it is one of the hazardous wastes that burden this enterprise.

About 2,146 official hazardous waste categories have been established by the EU, and only these items may be landfilled on its territory. All other materials must be “reused”33 or prevented from entering the waste stream altogether.34 Apart from asbestos, a future archaeologist would also find fly ash, dewatered sludge, and contaminated soil in this landfill layer.35 The amounts of each material would depend on the only metric with which the company is concerned: density. The math is simple, as the sales manager explains: “our customers pay by how small their waste can be made.” The less space it takes up, the better: “if it is sold too cheap, it is simply lost capacity.”36 On the far end, I see another truck entering the scene. According to the company’s website, its clients come from all types of industries, ranging from hospitality, agriculture, chemical, and textile companies to medical institutions and construction.37 In light of this steady customer flow, I cannot help but ask, “Could the EU even succeed in phasing out landfills, as their directive sets out to do?”38 He pauses briefly and then says, “Likely, there will be more. Who knows what new types of hazardous waste we will encounter tomorrow?” alluding to problematic chemicals such as PFAS, known to be “forever chemicals,”39 entering a never-ending waste stream.40 Not only does the future of reducing waste streams appear uncertain but so is the owner’s liability. As a rule, a landfill operator is held responsible for thirty years after closure.41 In the case of the company accepting hazardous wastes to form the Flemish Mountain, they might be held responsible for problems even past this legal requirement.42 How might they predict these faraway timelines, the sales manager wonders, even with their state-of-the-art engineering? “Can you help it?” He exhales and trails off. Lekkerkerk may have been a textbook example of responding to an environmental waste crisis at municipal and government levels,43 but more subtle leaks might not be met with the same urgency due to cost and setting potential precedent cases.44 This notion is amplified by environmental services companies in the Netherlands, which monitor landfills and their surroundings to this day for potential contamination.45 For the time being, the Flemish Mountain—this already sacrificed zone—will be kept open as long as possible to allow for waste with no other treatment options to be buried, even if this means extending the site further. To demonstrate the company’s thriving business model, the sales manager takes a pen to mark my latest satellite map.46 From its inception, the landfill has continued to grow sideways, eating up fields and swallowing a small house in its way. Today, it measures 18 hectares, a considerable size for any landfill.47 Bordered by the road and company offices to the east, it can now expand in only one direction: southwest. Eventually, the dry, sandy, gray soil I stood on moments earlier will be neatly folded into this archive of undisclosed hazardous waste.48

Scaling the Mountain

It is hard to grasp the scale of human waste in either spatial or temporal terms. This is perhaps why, as the anthropologist Joshua Reno reflects, the image of the familiar household bin is often evoked to visualize the practice of discarding.49 Featured in campaigns by the UK, NGOs, and municipalities—such as London’s famous 2007 “starve your bin” ad to encourage recycling—it has become a symbol to encourage “responsible consumerism.”50 These bins tend to be the first and last point of an individual’s contact with entangled contemporary waste management systems. While recent generations drove to the landfill and had their own waste weighed,51 this personal relationship with material flows is being increasingly severed. Over the past few decades, a complex network consisting of specialized waste trucks, recycling facilities, transfer stations, shipping containers, industrial holding ponds, waste incinerators, and more has emerged.52 Each element and actor within the network is paid to keep the urban center clean and healthy,53 while maintaining the illusion of Away.54 Citizens are just another wheel in the collective construction of Away, taught to perform the magic trick of disappearance from early on. Because these systems tend to function smoothly and out of the public eye,55 it is easy to forget, as the anthropologist Sophia Stamatopoulou-Robbins reminds her readers, that waste technology only “redistributes waste’s burdens, rather than make them disappear.”56 A case in point here is the waste incinerator, which appears to perform the much-needed magic trick: turning matter into air. While they do reduce waste in size and volume, toxic solid and gaseous residues always remain, with the former ending up in the very landfill it promised to avoid.57 In other words, all that contemporary waste management achieves is buying time.

Narrowing the public gaze onto the individual as both the culprit and hero of waste management through awareness campaigns and local waste management infrastructure shields citizens and industrial producers alike within the “center” from waste’s consequences on the “periphery.” Reducing individual waste output remains laudable, but industrial waste always statistically outpaces the domestic.58 The mind-boggling challenge therefore, as Timothy Morton writes, is to understand accumulated actions at scale to begin with.59 To demonstrate the scale of this paradigm’s collateral damage to ecosystems,60 scientists resorted to dating the human-made epoch, coining the term Anthropocene.61 Over the years, the term has caught on even beyond the sciences, within environmental movements such as Extinction Rebellion, or artistic research, like the Anthropocene Curriculum (HKW).62 Each of these responses uses the term Anthropocene to describe what “we” should do about living in extractive, discard societies. 63 As the environmental historian Marco Armiero observes, the term implies a problematic universalistic “we.”64 After all, “we may be all in it, but we are not all in it in the same way,” as his colleague Rob Nixon clearly underlined.65 Only a particular (imperialist) socioeconomic lifestyle practiced by wealthy members of heavily postindustrial and financialized economies has led all of us to the sixth mass extinction.66 Without a doubt then, the language used to frame this deterioration matters. Armiero therefore proposes the term “Wasteocene.”67 While forthright, this term seeks to differentiate between the producers within the urban center and the wasted places and lives on the receiving periphery. Unlike other -cenes, his lens leaves no ambiguity toward the systematic, unraveling consequences of Away across the globe.68 Within Armiero’s definition of the Wasteocene are the easily overlooked systems that govern, and direct waste accumulated by both the public and private industries toward the periphery. The anthropologist Mary Douglas suggests that there is no “dirt” (waste)69 unless there are systems that order and reject matter to begin with, which enhances that very center-periphery binary.70 The EU waste directive, devised much later than her research in the mid-1960s, could be seen as an example of how such a system governs. First, it captures and classifies all known and produced “dirt” as hazardous or non-hazardous waste and then, under this legislative governance, actors and waste technologies are to align on the ground accordingly.71 Despite a high level of control and monitoring in recent decades, waste streams are more open-ended than their final node—the wrapped-up landfill crater on the periphery—suggests. If one were to seek another way to date human-made impact, it would not be necessary to look far for geological evidence. For the Wasteocene has already inscribed itself into the tissue of our own bodies. Through the soil and food chain, chemicals such as PFAS, nitrates, and microplastics enter bodies even before birth.72 As a record keeper, the body is, to Stacy Alaimo, probably the most “powerful tool, a porous space, that absorbs and makes visible the toxic soup sponging everything on earth.”73 Standing inside the Flemish Mountain highlights the need to unpack Away through its waste classification systems, their governance, and their implementation on the periphery, particularly as legislation cannot prevent waste streams but instead slowly creates thresholds for what exposure may be acceptable for humans and more-than-humans alike.74 All the while, bodies have received Away, choking on its every false premise in both center and periphery.

On Care and Management

In early November, I make my next visit to Belvedere in Maastricht, a former 20-hectare landfill in the south of the Netherlands. There, I am greeted by Bas, who works for Bodemzorg (this translates roughly as Soilcare). A zoologist by training, his work is now caretaking this postnatural landscape near the river Maas, as well as fourteen others across the region. While his official title is project manager, I think of him as the carer of the mountain. Part of Belvedere is publicly accessible as a recreational area, but its 52-meter-high plateau was closed off two years ago. In lieu of reaching it, visitors may now marvel at a field of solar panels stretching out as far as the eye can see.75 As we reach the northern slope, I get a rare glimpse of the topography’s secret: the geomembrane. Erosion has exposed it. Next to me, Bas reaches down and nonchalantly pulls off part of the top layer for me to keep. It is a colorful rubber composite and a thin layer of woolly material still carrying bits of topsoil. Below me lies the last layer, a black plastic sheet: the center-sealing component of the landfill. Across the globe, there are many variations of the geomembrane—more a category than a single material component—from black, bendable plastic sheets to plastic grids cushioned with water-absorbent fabric liners. Whatever its composition, the intention is the same: to keep the buried strata, gases, and leachate under control.76 I study my newly acquired souvenir. It seems almost absurd that these three layers are all it takes to maintain the borders of Belvedere. Bas brushes his hands off and seems to notice what I am thinking: “No need to redo the full membrane,” he says. A few heaps of soil will do. Tackling erosion is simply part of “nature management.”77 Curiously, the term also includes contracting more-than-human workers: long-haired French goats whose primary duty is to keep grass levels low.78 Despite this cost-effective measure, they do come with some risk as their trampling over the slopes may increase erosion on the delicately engineered mountain.79 Even though geomembranes are state-of-the-art devices, they too can break.80

Underneath the plastic lining, the slow, cumbersome process of decomposition takes place. As landfills are literally wrapped in plastic—hermetically sealed—it is difficult to predict when a site will release its last breath of methane. As a matter of fact, Belvedere was predicted to have stopped belching already. It hasn’t. And so, Bodemzorg keeps waiting and safely burning off the greenhouse gas in a small adjacent facility. “Aftercare” is the telling term for these maintenance and monitoring activities.81 Unsurprisingly, aftercare is rather costly. This may explain why solar parks are built above active sites to supply the energy grid and regain value from what is essentially lost ground.82 Overseas in the US, the extensive cost of aftercare has led the waste industry to contemplate other technological interventions. A product called ClosureTurf® caught my attention. Manufactured in Austria and distributed by a Dutch company, the product promises to simultaneously replace animal grazing and manage erosion cheaply. It is an artificial grass carpet—made from plastics—at scale, no grazing required. Placed atop the landfill, the plastic grass is designed to blend visually into at least two types of landscapes; it is available in a green reminiscent of a Windows 95 screen display, or brown to emulate supposedly drier environments.83 The product’s advertising evokes the pastoral, if one ignores the black pipes still sticking out of it.

Laid out in its totality, ClosureTurf® can also be read as an agent. As much as it is artificial, so is the concept of an idyllic pastoral landscape. Conveyed in art from the Enlightenment, through early photography, and later tourist advertising, our notion of nature and wilderness has consistently been shaped by media.84 Nature TV programs like the BBC’s Blue Planet broaden and maintain the audience for these ideas.85 As Leo Kim observes in his essay “Nature Fakers,” the TV viewer is transported effortlessly to hyperreal ecosystems, typically devoid of the human figure, in places that appear wild and inaccessible. Despite its attempts at the documentary form, this show remains a nature drama and therefore a fiction.86 Similarly, goats graze innocently on a landfill, unaware that they are reproducing this culturally constructed and broadcast notion of idyllic nature. ClosureTurf® takes this idea a step further by simulating the ground, presenting a lush, airbrushed mountain when viewed, as intended, from afar.

Dissecting ClosureTurf® beyond its questionable appearance offers more insights into the dilemma of the Wasteocene. Following its supply chain, fossil fuels (dead matter) are imbued with life via extraction and its refined versions are transported to Austria, where they are turned into a nonlife replica of grass—“turf”—and then shipped to the US to be installed over matter piled up to decay. Along the route, the product necessarily implicates several territories through the logics of extraction–use–discard, creating both operational and wasted landscapes in the process. This chain illustrates the power dynamics inherent to the Cartesian individual. Premised on a clear line drawn between life (bios) and nonlife (geos), as suggested by the anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli as she defines “carbon imaginaries” in “Geontologies,”87 at any moment life might be instilled where there was supposedly none, and similarly life might be destroyed in the blink of an eye. Facilitating this industrial paradigm requires fantasies of control and subjugation of the environment, wherein anything might be instilled with vitality for a given cost-benefit calculation. Consequently, a forest may be cut down to make room for a landfill today,88 whereas tomorrow the same landfill might be reengineered as a hospitable environment, with new trees planted atop it. From this angle, it is easy to see why ClosureTurf® is an effective technological fix on the surface: an object representing Away’s manifold challenges. It sweeps both waste and any reflection of the product’s raison d’être under the furry plastic carpet.

Elsewhere, the Vall d’en Joan, near Barcelona, Spain, evokes a similar hyperrealistic impression of nature. For forty years, until the early 2000s, the site received municipal waste. In 1998, it was designated a nature reserve on paper, while the site was still a bare ruin. Plans were contemplated to clear out the waste and fully remediate the area. Ultimately, due to the expected high cost, the city decided that the inverted mountain should remain, and BatlleiRoig, a local landscape architecture studio, was given a brief to propose a design that would visually and functionally integrate the postnatural landscape into Barcelona’s peripheries.89 Maastricht’s Belvedere seems laughably small in comparison when one views plans of this 70-hectare area, deep enough to bury the iconic Sagrada Familia. As the architects considered the challenge ahead, they understood their difficult position. Mario Super Diaz, a senior architect, reflected on the project: “We knew that we had to, essentially, create a new biosphere, but humans can’t create nature nor ecosystems. It would be a disaster. What we do know how to do is agriculture, however, formed life,” he said.90 A multidisciplinary team consisting of landscape architects, agricultural engineers, and environmentalists assembled to turn the valley into a “new agricultural landscape through topography, hydrology and vegetation.”91 Soil would be the team’s starting point.92

Typically, lower-quality grades or artificially created soil—known as technosols—are placed upon geomembranes.93 To “bring back life,” however, the team created their own topsoil by enriching it with straw and utilizing composting processes. Sheep and cows were introduced to add manure and nutrients to the soil. Lastly, pines—banned from the city due to their shallow branching roots—were added for this very characteristic. This would stabilize the soil, and the roots would not disturb the delicate geomembrane underneath.94 Since the completion of Vall d’en Joan, below hooves, technosoil, and geomembrane, the remaining methane gas has been slowly funneled from the highest to the lowest point in the valley. There, it will be safely burned for another forty years, feeding the local energy grid. Picturing the meticulously planned and realized terraces featured on the architects’ website across different seasons, it appears that, in Povenelli’s term, “life” has always been there.95

Nearing Away

Redeveloping wasted places not only for public safety but to “restore life” above them is laudable. Once wasted places have been created, indeed, there seem to be few alternatives even though the task of remediation can be long, expensive, and unrewarding. In other cases, where space is scarce, like in the Netherlands, the possibility of reuse may promise new assets, such as a hospital and a golf course in the same location.96 In today’s moment of ecological collapse, including extreme habitat loss, postnatural landscapes such as the pastoral Spanish valley or waste mountains in the US covered with ClosureTurf® raise different questions. Which visions of nature do they re-create? Might they be distracting from the Wasteocene, in the same way that eco-media tends to portray “pristine” nature unaffected by imperialist lifestyles premised on the idea of endless growth?97 Importantly, neither aftercare nor nature management as described in these instances questions the fundamental paradigm of Away. On the contrary, they seem to unwittingly enable the opposite: the center’s continuation premised on the periphery. After all, if the center can build upon its own ruins with the help of more-than-human actors or plastic carpets that create the illusion of repair and control, then there is no need to question the creation of newly wasted places overall. While Away separates some people from waste in its most literal sense, it upholds divisions between humans and the very ecosystems—including all other life forms—upon whom we depend.

As I write these concluding words, The Guardian announces the sinking of an old Brazilian aircraft carrier full of asbestos,98 the type of waste I encountered in the inverted Flemish Mountain. Safe deconstruction on land was not an option. It seems as if the periphery is creeping into the center from all sides. And with shrinking habitable territory, there is no doubt that cases like these will arise more frequently. What might we trade against each other: ocean ecosystems against arable land, or a forest against a future landfill? The logic and boundaries of Away will become even more fluid as a result, continually redefining the “geospatial other.” Questioning Away requires both zooming out from the image of a familiar household bin and the belief that technology will fix it all in the end. Make no mistake: discarding per se cannot be avoided.99 Instead of producing wasted places—and by extension, contaminated bodies—how might we abolish the borders of center and periphery? What ways of discarding would support that? And ultimately, how might we approach habitats differently? Without a doubt, we will need to draw near the sacrificed zones consciously and unflinchingly if we are to arrive at a different understanding of our deep entanglements in the Wasteocene. Refusing to remember these designed decisions, or failing to look at the periphery, would constitute the worst versions of Away.

-

The company did so well in shielding the site that someone even purchased a house nearby, oblivious to its presence. Personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 12, 2022. ↩

-

Neil Brenner, “The Hinterland Urbanized,” Architectural Design 86 (2016): 118-127, cited in Clara Olóriz, ed., Landscape as Territory: A Cartographic Design Project (New York: Actar, 2020), 12; Google Earth Pro 7.3, Flemish Mountain (anon.), elevation 200 meters, 2D map, viewed July 10, 2022, link. ↩

-

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, translated by W. Weaver (London: Vintage Classics, 1997); Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity, 2003). ↩

-

Dipesh Chakrabarty (1992), cited in Marco Armiero, Wasteocene (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 2. ↩

-

Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen, Imperiale Lebensweise: Zur Ausbeutung von Mensch und Natur in Zeiten des globalen Kapitalismus. München: Oekom Verlag GmbH, 2017. ↩

-

Dipesh Chakrabarty (1992), cited in in Armiero, Wasteocene, 2; U. Brand and M. Wissen, Imperiale Lebensweise: Zur Ausbeutung von Mensch und Natur in Zeiten des Globalen Kapitalismus (Munich: Oekom Verlag, 2017). ↩

-

Robert Ascher (1974), cited in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, ed. P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, and A. Piccini (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 4, link. ↩

-

Ben Cosgrove, “‘Throwaway Living’: When Tossing Out Everything Was All the Rage,” Time, May 15, 2014, link. ↩

-

M. V. Helvert, ed., The Responsible Object: A History of Design Ideology for the Future (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017); Ascher in Graves-Brown, Harrison, and Piccini, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, 4; Frank Trentmann, Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First (New York: Penguin, 2016). ↩

-

K. O’Neill, Waste (Cambridge: Polity, 2019); Bauman, Wasted Lives. ↩

-

Google Earth Pro 7.3, Landgoed Gulbergen, 51°26'57.37"N 5°34'27.58"E, elevation 340 M. 2D map, viewed September 3, 2022, link; Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (AHN), link. ↩

-

In 1971, the municipality of Lekkerkerk granted an obstacle law permit for the dumping of waste by the container company Wijnstekers, based in nearby Rotterdam, in which no control was carried out on what exactly was dumped. See NTR, “Lekkerkerk.” ↩

-

H. Van Grinsven, Lekkerkerk (1979), Nederlandse Bodemkundige Vereniging, September 7, 2004, link; WMW, “Problem or Opportunity? How to Deal with Old Landfills,” March 1, 2008, link. ↩

-

O’Neill, Waste; William Rathje, “Garbologist–Talkin Trash,” 2021, Youtube, link. ↩

-

Nicholas P. Cheremisinoff, “Treating Contaminated Groundwater and Leachate,” in Groundwater Remediation and Treatment Technologies, ed. Nicholas P. Cheremisinoff (Westwood, NJ: William Andrew Publishing, 1997), 259–308, link; US EPA, Landfill Methane Outreach Program, “Basic Information About Landfill Gas,” 2016, link. ↩

-

Sustainability for All, “Landfills: A Serious Problem for the Environment” (n.d.), link; E. Robb, “No Time to Waste: Waste Management and Methane,” Zero Waste Europe, September 17, 2020, link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Jan Frank Mars, EU COCOON project (NL contact), September 28, 2022; personal conversation with Eddy Wille, EU COCOON project (BE contact), September 23, 2022. ↩

-

See the Zuiderzee land reclamation project starting in 1924, which led to another whole new province, called Flevoland. After road networks and infrastructure were completed, they too would have two of their own landfills. See Nationaal Park Nieuw Land, “Flevoland’s History,” link; COCOON Consortium for a Coherent European Landfill Management Strategy, “Rijkswaterstaat Environment” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Translates as “Aftercare Former Landfills.” ↩

-

Provincie Noord-Brabant Directie Ecologie, “Hergebruik van stortplaatsen Van bedreiging naar kans,” June 2004, link; personal conversation with Roger Smeets, strategic policy officer landfills, Province of North Brabant, Netherlands, December 14, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Roger Smeets, December 14, 2022; COCOON Interreg Europe, “Landfill Management in the Netherlands,” May 3, 2018, link; Interproviciale Werkgroep Nazorg, “*NAVOS” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Local environmental services in collaboration with labs were tasked to do the investigations, mapping and reporting on the landfills. Among them were Fugro and Royal Haskoning, Tauw, and Ivaco. Some of these reports can still be accessed. ↩

-

EUR-Lex, “Proposal for a COUNCIL DIRECTIVE on the Landfill of Waste,” May 24, 1997, link. ↩

-

COCOON, “Interreg Europe” (n.d.), link; European Parliament, “Sustainable Waste Management: What the EU Is Doing,” April 6, 2018, link. ↩

-

European Commission, “Waste Framework Directive” (n.d.), link; European Commission, “Follow-Up Study on the Implementation of Directive 1999/31/EC on the Landfill of Waste in EU25,” June 2007, link; European Commission, “Environment in the EU27: Landfill Still Accounted for Nearly 40% of Municipal Waste Treated in the EU27 in 2010,” March 27, 2012, link. ↩

-

Rijkswaterstaat, “Europe: COCOON Consortium for a Coherent European Landfill Management Strategy”; European Commission, “Follow-Up Study.” ↩

-

European Environment Agency, “Municipal Waste Landfill Rates in Europe by Country,” January 22, 2024, link. ↩

-

Masashi Soga and Kevin J. Gaston, “Shifting Baseline Syndrome: Causes, Consequences, and Implications,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16, no. 4 (2018): 222–230, link; Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds., Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

-

Discard scholars argue that recycling is not a viable solution for it requires high expenditures of energy, some virgin materials, and it produces pollutants as well. On a secondary level, it naturalizes disposables intead of foregrounding redesign and elimination. One of its most vocal critics, Samantha MacBride, argues that certain industries support recycling efforts, even though they are neither sustainable nor profitable enough without subsidies. Indeed, recycling has turned into a market like any other between centers and peripheries. For more, see MacBride, as well as Steinberger, Krausman, and Eisenmenger. ↩

-

Samantha MacBride, Recycling Reconsidered: The Present Failure and Future Promise of Environmental Action in the United States (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013); Max Liboiron and Josh Lepawsky, Discard Studies: Wasting, Systems, and Power (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022). ↩

-

See the waste directive hierarchies on the European Commission website: “Waste Framework Directive,” link. ↩

-

European Commission, “Commission Notice on Technical Guidance on the Classification of Waste,” April 9, 2018, link. ↩

-

Company website of Flemish Mountain Waste. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 7, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 7, 2022; company website of Flemish Mountain Waste. ↩

-

The EU incentivizes the phasing out of landfills via taxes and penalties (for dumping non-hazardous wastes), particularly in member states, though all EU Cocoon interview partners agree unisono that zero landfilling won’t be realistic. ↩

-

PFAS are industrial chemicals that have become infamous due to their polluting characteristics. Their use is widespread in textiles, electronics, firefighting foam, and and in many other applications. These chemicals have been found in the bloodstreams of humans and animals alike. ↩

-

Alan Hope, “PFOS Pollution: Local Family Files Legal Complaint Against 3M,” Brussels Times, June 23, 2021, link; US EPA, “PFAS Explained,” March 30, 2016, link; Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen, “Per- und polyfluorierte Alkylverbindungen (PFAS),” link; personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 12, 2022. ↩

-

Rijkswaterstaat Environment, “COCOON Consortium for a Coherent European Landfill Management Strategy”; personal conversation with Jan Frank Mars, September 28, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 12, 2022. ↩

-

NTR, “Lekkerkerk.” ↩

-

In conversation with a local Dutch environmental services company, it was revealed that if they were to find contaminants caused by landfill leakage and it had to be remediated at substantial cost, then this may set the precedent for other landfills to be remediated too at high cost, the implication being that it would not be clear how this may be financed. Still, their goal is to achieve remediation were they to deem it harmful. ↩

-

Personal conversation with environmental service company (anon.), April 2, 2024. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Flemish waste company (anon.), July 12, 2022. ↩

-

Google Earth Pro 7.3, Flemish Mountain. ↩

-

Google Earth Pro 7.3, Flemish Mountain. ↩

-

J. Reno, “Waste,” in Graves-Brown, Harrison, and Piccini, eds., The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, 4. ↩

-

Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies; O’Neill, Waste; European Week for Waste Reduction, “Tools” (n.d.), link; letsrecycle.com, “Londoners Urged to Recycle Three Times More Waste,” October 15, 2007, link; Eduka, “B-Cycle Battery Recycling Campaign” (n.d.), link; Carton Council, “Digital Campaign with Recycle BC,” April 19, 2024, link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Anna Felbinger-Forster (maternal grandmother), Grünburg, Austria, December 16, 2022; personal conversation with Karl Schmeisser (father), Bad Hall, Austria, December 17, 2022; personal conversation with a local from Nuenen, Netherlands, May 9, 2024. ↩

-

Rania Ghosn and El Hadi Jazairy, Geographies of Trash (New York: Actar, 2016); O’Neill, Waste; European Commission, “Landfill Waste” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

China purchased recycled plastics from the US and other wealthy nations (including higher-quality scrap) to feed its growing manufacturing centers. It put a halt to that practice as it received contaminated waste that wasn’t easily reprocessed; see O’Neill, Waste. ↩

-

O’Neill, Waste; Bauman, Wasted Lives. ↩

-

The occassional fire at landfills, the “waste river” of Beirut, and recycling centers on fire show the cracks and crises of modern-day waste management. Yet these crises are typically brought under control quickly enough so that the center may also continue. Others, such as the landfills of New Delhi, on the other hand, continue to be both a long- and a short-term crisis. See a few selected examples across the globe, such as: “Bury Landfill Fire: Dramatic Footage Shows Scale of Blaze,” BBC, April 27, 2021, link; “Beirut’s River of Garbage, in Pictures,” The Telegraph, March 20, 2016, link; Ciara Nugent, “Why Recycling Plants Keep Catching on Fire,” Time, April 13, 2023, link; “Großbrand in Recyclinganlage in Klagenfurt,” Kaernten, November 23, 2014, link. ↩

-

Sophia Stamatopoulou-Robbins, Waste Siege: The Life of Infrastructure in Palestine (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), quoted in Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies, 71. ↩

-

S. Samuel, Bitte hier keine Schlacke deponieren (Zurich: Hochparterre, 2019), 32–37; Zero Waste Europe, “Incineration Residues: The Dust Under the Carpet,” 2022, link. ↩

-

Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies; European Parliament, “Sustainable Waste Management: What the EU Is Doing.” Note: this website and its content has been since updated. ↩

-

T. Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); Elisa Gabbert, “Big and Slow: How Can We Represent the Threats That Are Too Vast to See? What If Civilization Itself Is One of Them?” Real Life, June 25, 2018, link. ↩

-

Brand and Wissen, Imperiale Lebensweise. ↩

-

In 2015, researchers Maslin and Lewis presented two Antarctic ice cores as evidence. In them, unusual and significant increases of CO₂ levels are recorded, and scientists have been able to link the spike back to the colonial project after 1600. Mass destruction of indigenous communities, cessation of certain agricultural practices, and deforestation were said to be the cause. Called the “Orbis spike,” it was striking insofar as it depicted for the first time not only destruction on a global scale caused by man and showed the far-reaching roots of Away through the centuries. See also UCL News, “Epoch-Defining Study Pinpoints When Humans Came to Dominate Planet Earth,” March 11, 2015, link; Michael Franco, “ ‘Orbis Spike’ in 1610 Marks Humanity’s First Major Impact on Planet Earth,” Cnet, March 12, 2015, link. ↩

-

“Home | Anthropocene Curriculum,” link; Extinction Rebellion, “Anthropocene: The Definition, the Debate, and You,” link. ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene; UCL News, “Epoch-Defining Study Pinpoints When Humans Came to Dominate Planet Earth”; W. Lucht, “ Planting the Anthropocene’s Roots in Globalization,” Nature, June 16, 2018, 26–27, link; P. Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415, no. 23 (2002), link. ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene; Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies. ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene; Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies. ↩

-

Max Liboiron’s work Pollution Is Colonialism illuminates that pollution is a symptom of the violent enactment of colonial land relations that claim access to Indigenous land. See Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021). ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene. ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene. ↩

-

There has been debate among scholars on whether to call waste “surplus material” instead, meaning “material that we failed to use.” Zsuzsa Gille is one of the proponents of the term, for often, at least at municipal waste level, there is often little choice when purchasing goods. See her paper titled “Actor Networks, Modes of Production, and Waste Regimes: Reassembling the Macro-Social.” In this essay, I will mostly follow the industry terms “municipal wastes” and “hazardous wastes” since I am predominantly referring to the landfill and these have been classified in this way. In addition, “hazardous wastes” would not fall eithin her definition, for these are often byproducts of industrial processes and industries that can’t be reused and should be at best avoided or replaced with alternatives where possible. ↩

-

M. Douglas, Purity and Danger (London: Routledge, 2002); Chakrabarty in Armiero, Wasteocene, 2. ↩

-

European Commission, “Waste Framework Directive.” ↩

-

Hope, “PFOS Pollution”; L. Parker, “Microplastics Are in Our Bodies. How Much Do They Harm Us?” National Geographic, May 8, 2023, link; DW, High Levels of Nitrate in German Water,” September 9, 2016, link. ↩

-

Armiero, Wasteocene, 12; S. Alaimo, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010). ↩

-

Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies; European Commission, “Nitrates” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Bas Jenniskens, Bodemzorg Limburg, November 1, 2022, Maastricht, Netherlands; Soilcare Limburg, “Belvedere” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Genap, “Genap Distributor, ClosureTurf,” 2022, link; Walcoom, “Geotextile for Road, Landfill, Highway, Pond, Tunnel, Slope” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Bas Jenniskens, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

The term was coined by David Abram and was taken up by scholars such as Donna Haraway to describe our entanglement with the ecosystem and thereby our dependencies on other beings. Further reading on the term may be found in Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble (Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), and in Abram’s original work, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: Vintage, 1997). ↩

-

Personal conversation with Bas Jenniskens, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Mario Super Diaz, Senior Landscape Architect, BattleiRoig, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Bas Jenniskens, November 1, 2022; Provincie Noord-Brabant, “Nazorg Operationele Stortplaatsen” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Provincie Noord-Brabant, “Duurzaam Stortbeheer” (n.d.), link; Bodemzorg Limburg, “Belvedere” (n.d.), link; personal conversation with Bas Jenniskens, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Genap, “Genap Distributor, Closure Turf”; “WatershedGeo - Closure Turf,” 2015, link; AGRU America, “ClosureTurf®,” March 24, 2023, link. ↩

-

Harriet Mercer, Review of Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism, Jarrod Hore, Western Historical Quarterly 54, no. 4 (December 2023): 361–362, link. ↩

-

Leo Kim, “Nature Fakers,” Real Life, September 23, 2021, link. ↩

-

Y. N. Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, illustrated edition (New York: Harper, 2015); Kim, “Nature Fakers.” ↩

-

E. Povinelli, “Geontologies: The Concept and Its Territories,” e-flux 81 (April 2017), link. ↩

-

In Switzerland, the burden of contemporary waste management, and recycling in particular, has instigated a conflict between a local activist group and a forest that is destined to give way to a landfill for the residues of the recycling plant. The argument from the proponents’ side is that in the speculative future anything of value might be mined out of it and the forest may be reinstalled. The activists are rather skeptical of this speculative promise. See S. Schmeisser, “Trading Futures,” Unruly Natures, March 24, 2024, link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Mario Super Diaz, Senior Landscape Architect, BattleiRoig, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Mario Super Diaz, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Batlleiroig, “Restauració paisatgística del Dipòsit Controlat del Garraf a Barcelona” (n.d.), link. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Mario Super Diaz, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Jan Frank Mars, September 28, 2022. ↩

-

Personal conversation with Mario Super Diaz, November 1, 2022. ↩

-

Batlleiroig, “Restauració paisatgística del Dipòsit Controlat del Garraf a Barcelona.” ↩

-

DCMR, “Stort Sint Franciscusdriehoek,” link. Google Earth Pro 7.3, Stort St. Francis Triangle, 51°56'38.2"N 4°27'48.3"E, elevation 1.2km. 2D map, viewed 12.5.2024, link. ↩

-

Brand and Wissen, Imperiale Lebensweise. ↩

-

Agence France-Presse, “Brazil Sinks Aircraft Carrier in Atlantic Despite Presence of Asbestos and Toxic Materials,” The Guardian, February 4, 2023, link. ↩

-

Liboiron and Lepawsky, Discard Studies. ↩

Sigrid Schmeisser is a designer and researcher whose practice, Peak15 (est. 2016), is characterized by a site-responsive approach and a range of multimedia outcomes. She investigates discard studies in the related project From Centre to Periphery by focusing on landfills as postnatural landscapes, which she reframes as landbodies. It has been translated into a lecture performance (DutchDesignWeek 2023), documentary photography, and art publications. This essay was developed from her Geo-Design master’s thesis, “How to Hide a Mountain,” mentored by Nadine Botha (DesignAcademy Eindhoven).