1. Dry-erase board; a single capless marker in the marker holder; “CAPTURE an IMAGE” fading but still visible in large letters at the center of the board; an upside-down stick figure in the top left corner with streaks through it, like someone tried to erase with their fingers; no eraser in sight

It’s a Friday afternoon in December when I get a blast email from the University of Arizona’s Office of Public Safety. I am a second-year MFA candidate at the university, and I am alone in a classroom where I’ve just finished teaching. Often, I can’t even believe I made it here: back to the classroom at age thirty-two, after everything.

My whole young life, I’d been an honors student, in part because I truly loved to learn, but also for the simple reason that good grades translated into scholarships. My father, the smartest person I know, didn’t graduate high school, and I witnessed the way the shame of this quietly ate away at him, despite how brilliant I knew he was. I wanted to write a new story for my family. And, after graduating high school a year early, I was on my way to doing that—then I was raped. Like tens of thousands of others like me, I was promised safety by the same university where I was sexually assaulted by a classmate. Rape is the most underreported crime in the US1—and still, over a quarter of undergraduate women and nearly seven percent of men report experiencing sexual violence “through physical force, violence, or incapacitation” during their time in college alone.2 Universities make promises of safety to their students—and then fail to protect over a quarter of them from life-altering violence. What are our universities focusing money, time, and energy on if not on protecting their students?

My eyes flick from dry-erase board to poster to abandoned pencil to window. White, blue, mustard, green. I count my breaths. It is Day 70 of the Palestinian genocide. We are calling it Day 70, but really it is Year 76. Really, the current genocide in Palestine is part of a larger continuum of violence that the West has been inflicting upon Palestine and its Indigenous people for nearly a century.3

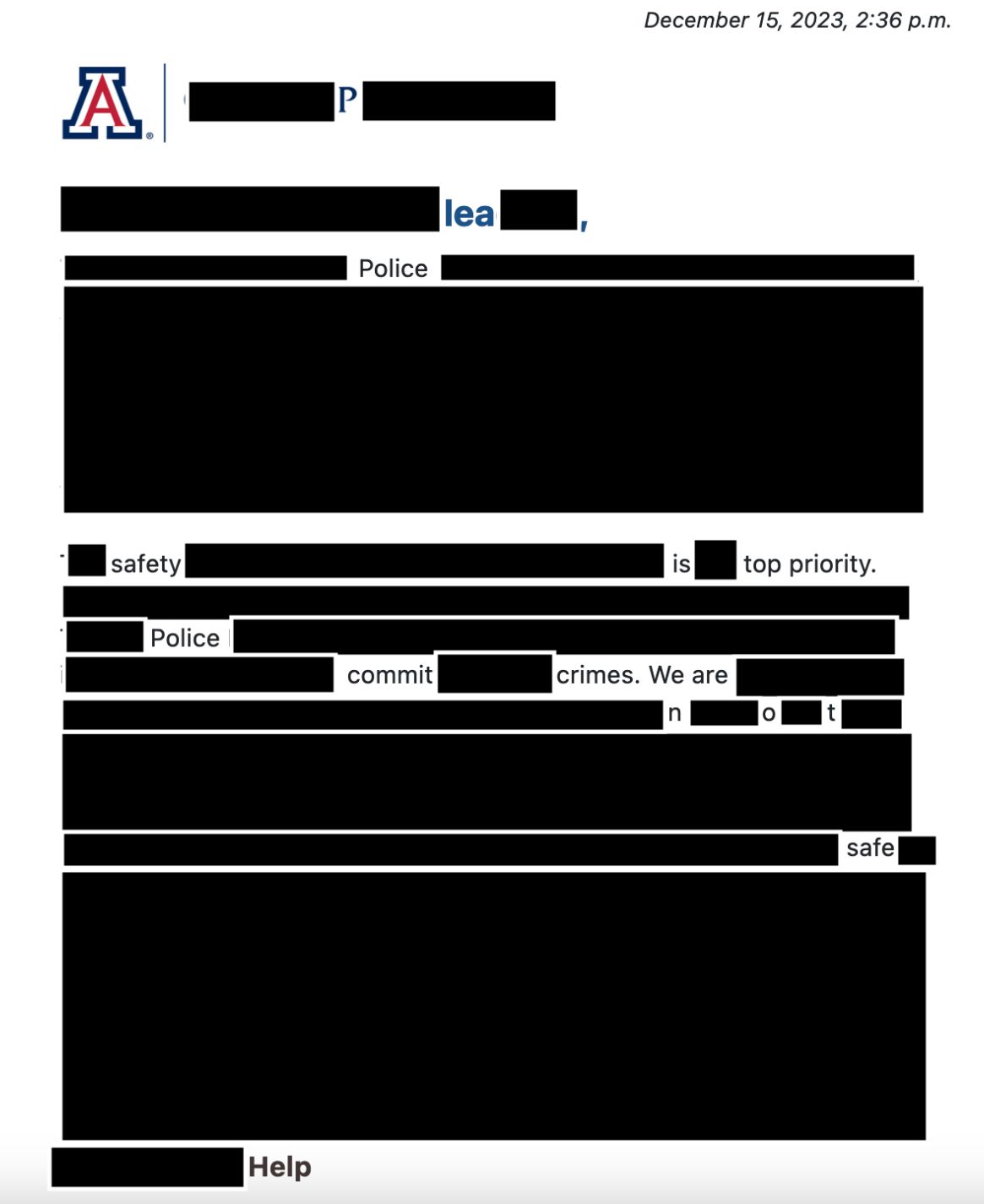

The email from my university’s Office of Public Safety says that they are going to “increase the presence of law enforcement officers on campus and in surrounding areas” through a collaboration between the UAPD and the Tucson Police Department. They say this is for our safety.

As of August 21, 2024, there have been ten days this year that police have not killed someone in the United States. Here in Arizona, Black people are 3.5 times more likely to be killed by police than are white people like me.4 What kind of violence does a university with a diverse student body invite when it collaborates with a police department that received 2,024 civilian complaints from 2016 to 2019—and that resolved zero complaints of police discrimination in favor of civilians?5

I glance over the email from the Office of Public Safety and notice some words lifting off the page, as if made three-dimensional by some kind of truer vision. I think about the truth that is present in every document, despite an institution or an oppressive culture trying to hide it. I think about what the university is admitting to—even just in this email—with the language it uses. Police. Unwanted. Crimes. Police. Sexual. Officers. Suspect. Police.

Next to the whiteboard, by the classroom’s door, is a bulletin board lined with navy blue paper. A lime green flier with the title “Campus Safety” is pinned in the center of the board. I can’t read the rest of the text; I’m too far away. I wonder what it could tell me about danger that I don’t already know.

Concept: According to a 2022 study, bisexual people like me experience rape/sexual assault at a rate that is eighteen times that of straight people.6 According to a 2010 study, people are two times more likely to be sexually assaulted by the police than by members of the general public: after excessive force, the second-most reported form of police misconduct is sexual violence.7

Practice: When I was an undergrad at a different university, I didn’t report my own rape after it happened. Poetry—at least the kind I admire—is proof of survival. Poetry is a place where shrapnel exists alongside the silences it produces. It is a place where readers are asked to give both the screaming and the silence equal consideration.

Concept: On a physical page, identifying silence can be a fairly easy task: look for blank space. What comes next is holding the silence alongside what is written, allowing both text and space to exist, and then asking the question: What is the relationship between the two?

Practice: My first therapist in Tucson told me it was “common” for her to encounter women who had been raped by Customs & Border Protection (CBP) officers. The women she was talking about were white women; they were citizens. They were women who live in the United States, who have more readily-accessible resources to report and seek treatment, and who, compared to women of color, were much more likely to be believed. Still, they were assaulted. What does this mean for the actions of these same officers when they aren’t being watched? What is the gap that this information implies? How big is the silence?

My eyes flick to the desk nearest me. Someone has carved their initials in a corner of the wood: JBC, the same as mine.

2. Land acknowledgment in Program-Director-Who-Is-Racist-Toward-Indigenous-People’s email signature

The Sonoran Desert, where Tucson is located, is the most biodiverse desert in the world.8 It is the ancestral homeland of the Tohono O’odham, Yaqui, and Pima people.9 It is also home to 100,000 square miles of desert that lines the US–Mexico border—a border delineated by bloodshed that is continually enforced by empire’s strong-arm, making it the deadliest border crossing in the world.10 Living in Tucson means recognizing the beauty and also the violence that the landscape shares with us. It is not a coincidence, for example, that Indigenous people being continually and forcibly removed from their homelands results in deteriorating environmental and humanitarian conditions for everyone.11

Tucson, the city’s Spanish name, comes from the O’odham S-cuk Son, which means “at the base of the black hill.”12 Prior to settler colonial disruption and brutality, O’odham life was sustained in part by the Santa Cruz River, which flowed perennially along the hill’s base.13 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, after settlers started using groundwater pumps, the water table dropped drastically, and by 1950 the flow of the river was completely gone.14 The hill, also called Sentinel Peak, a central marker of the ancestral homelands of the Tohono O’odham, can still be seen today—with an enormous, hideous “A” branding its face.

Tucson’s plan for the land at the base of A Mountain has been under discussion for decades. Between 1953 and 1962, the land was used as a landfill.15 In 1999, voters passed Proposition 400, which “used state sales tax dollars for cultural development and restoration of the area.”16 What voters didn’t know—or what had been purposefully erased from the conversation—was that this land was contaminated by toxic waste—namely methane gas from the aforementioned landfill.17 The wild fact that settlers had put a landfill next to their water source aside—plans for cultural development fell apart.

In 2023, Tucson mayor Regina Romero announced that Tucson was going to return 10.6 acres of land at the base of Sentinel Peak to the Tohono O’odham Nation. “It is essential to recognize and correct the historical harm that has been inflicted upon Indigenous peoples, including the Tohono O’odham People,” Romero said upon announcing the transfer of the land—which is (still) rife with methane and other pollutants—to the Nation.18

Stand in front of Caterpillar’s Tucson headquarters, and you are also standing in front of A Mountain. Google Maps says it is an 1.8 mile from the headquarters to the peak, but this includes a route that circumvents the land returned to the Tohono O’odham. The reality is that Caterpillar, the “world’s leading manufacturer of construction and mining equipment,” and A Mountain are next-door neighbors.19 In their ongoing genocide of Palestinians, the IOF uses CAT equipment to destroy water pipes and other structures necessary for survival, to uproot olive trees, and to demolish homes across occupied Palestine.20 From stolen land in S-cuk Son to stolen land in Palestine, Caterpillar’s financial success depends on genocide of Indigenous peoples. Through programs like the “Mining 360 Program,” the University of Arizona secures its place in Caterpillar’s longstanding legacy of global atrocity. 21

In poetry, we look both at what is present/visible and at what is missing/open on a page—and we interpret both. When we see the sacred land colloquially known in Tucson as “A” Mountain, we can see flat ground beneath the “A”—signaling the delicate ecosystem of our desert razed for the comically large white “A.” We can see litter sprouting from the earth and CAT looming large in the foreground. In this landscape, who has decided what is visible text and what is hidden? And is it not a colonized mind that relies on binaries like this in the first place?

Knowing what we know about CAT and UA, it only makes sense that the university would have a relationship with Raytheon Missiles & Defense, another multibillion-dollar company headquartered in Tucson.22 The truth is always one angle away from revealing itself.

3. American flag; bolted to the wall

The “A” on A Mountain came into being in 1914. It will come as no surprise that this happened because of the UA football team. UA played a game against Pomona College on Thanksgiving Day 1914, where one of the Arizona players noticed that Pomona College had the letter “P” branded into their hillside (which Pomona actually lit on fire with flares during football pregame rallies for years, until the Forest Service prohibited “the lighting of the letter” in 1926) and decided that UA needed one, too.23 A university civil engineering class started work on the project—clearing cactus, digging trenches while scarring the land, and gathering the basalt rock to form the “A.” This took two years to complete.24

Already, the clearing of cactus—a living thing—is violence. Saguaros in particular are central to Tohono O’odham identity: not only do saguaros represent the creation and ancestry of the O’odham but the O’odham also divide the year into 13 lunar segments, the first of which is called Hashañi Mashad, or Saguaro (harvest) month.25 Being located in the richness of the Sonoran Desert, Tucson’s plant, animal, insect, and human life forms are interdependent. Indiscriminately clearing cactus from the side of a culturally significant landmark to erect a useless monument to fragile masculinity is, at once, deeply offensive and deeply unsurprising from whiteness, here epitomized by the men of UA football. What’s more: city regulations required that the “A” be painted white. The University of Arizona literally whitewashed Tohono O’odham land, thus beginning an annual tradition of Arizona students gathering to paint the “A” white in celebration.

It is not a new or revolutionary practice: to witness something and contemplate what was there before. But with this I mean to say more. What if we were to examine the world around us as we would a historic document? What are landscapes if not palimpsests, if not messengers of what has come before?

This is what I find so fascinating about erasure work: the worlds that allow themselves to be seen if we look hard enough. A product of white supremacy will always be a product of white supremacy, and it is often hidden in the fine print that this becomes so clear. An email from a US university will always be an email languaging white supremacy. I, a US citizen whose tax dollars fund genocide and who actively benefits from systems of oppression, will always be a product and producer of violence.

Despite a person, an institution, or an imposing culture trying to hide it, the truth exists as it always has, and it wants to be seen. “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them,” writes James Baldwin in Notes of a Native Son.26 Loudness means nothing if there is no silence to contrast it. Even in attempts at silencing, the truth exists, at once fragmented and whole.

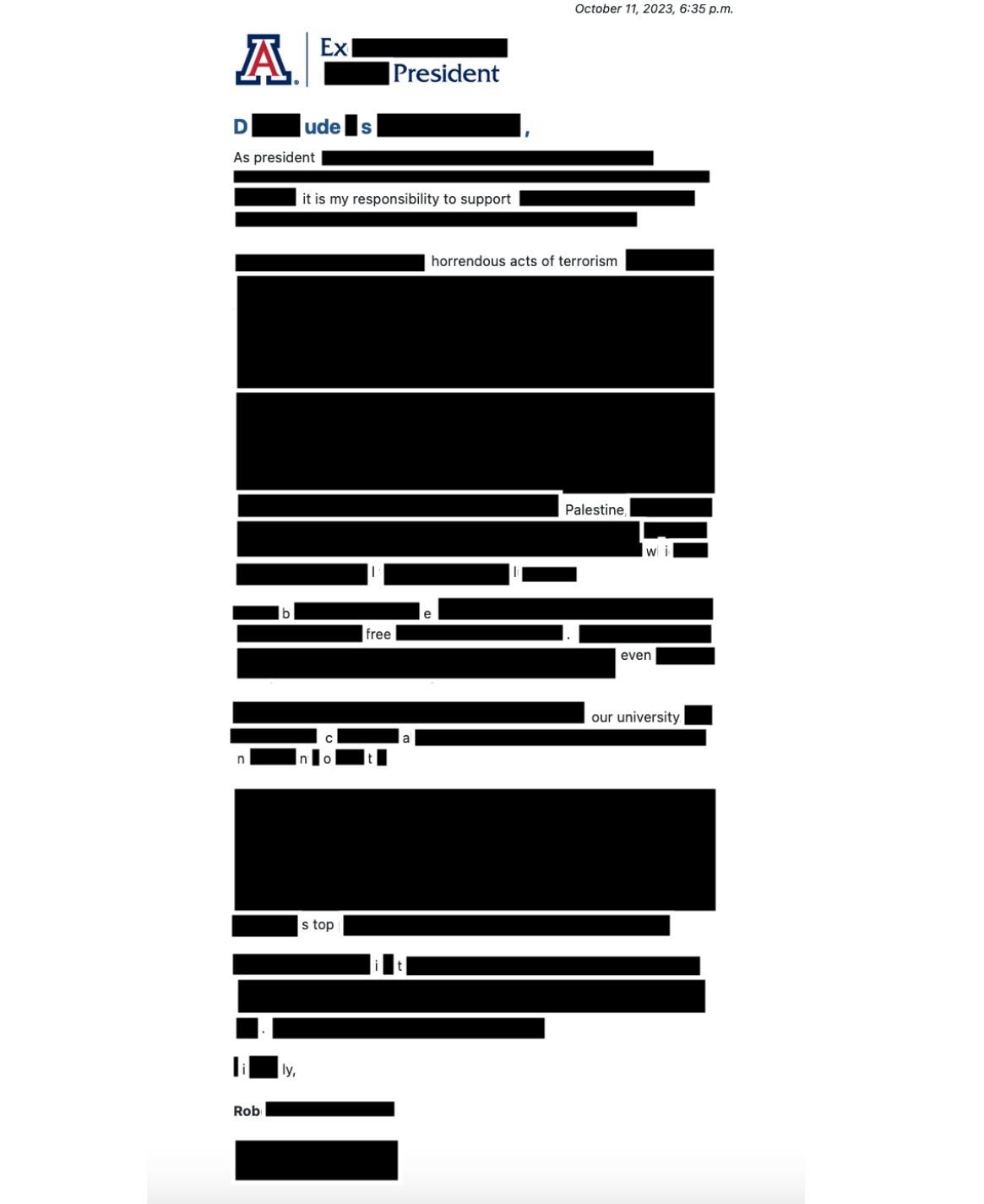

October 7, 2023, and the days that followed were ones the (otherwise oblivious) international community watched in horror. For millions, the horror escalated as it quickly became evident that the Israeli settler-colonial state was weaponizing the deaths of its settler-citizens to justify the genocide of thousands and thousands of innocent people. Devastated, enraged, and terrified, people across the world rapidly began to organize peaceful protests to demonstrate solidarity against this latest phase of Zionist settler-colonial violence. Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) at UA planned an October 12 rally, demanding that the “US government and University of Arizona disinvest from Israeli apartheid and violence against the Palestinian people.”27

Only four days after October 7, everyone on the UA listserv received Robert Robbins’s above statement supporting Israel. We at University of Arizona have international students from at least 48 countries.28 What are we being told by Robbins’s decision to act only when Israel is involved? If his motivations were printed out in a document, what would he want to be redacted?

From such a response, it feels almost as if the University of Arizona has direct ties to Israel. Almost as if the university relies on Israeli funding and is perhaps a recipient of millions of dollars in US–Israel Science Binational Foundation grants.29 As if the UA basketball team received a fully funded tour to Israel, including excursions to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, thanks to partnership with Athletes for Israel.30 Perhaps the University of Arizona also benefits from research collaborations with the Israeli Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.31 With such a tangible financial connection, Robbins’s unconditional support would make sense.

Because of the email that was sent from the Office of the President encouraging counter-protesters to “embrace [their] First Amendment rights,” SJP was forced to reschedule their peaceful protest due to safety concerns for participants and the greater Tucson community. Robbins made it clear whose safety—and funding—matters to him and to the university. In short: he showed his ass—and there is no amount of word salad that can hide the truth of his email: Palestinian lives do not matter to the University of Arizona.32

4. An educational poster of the Constitution of the United States of America’s Bill of Rights, laminated and pinned to the wall beneath an American flag; pristine condition

In a classroom just like the one I’m sitting in now, the poet John Murillo visited our MFA cohort. Someone asked him a question about silence in his work. He talks about music. About tension. About control. He says, “White space is to the page what silence is to the air.”

“We are enveloped in thick layers of gunpowder and cement. There are several bombs and shells each and every single minute. It’s suffocating,” posts Dr. Refaat Alareer, a scholar and poet from Gaza, on December 3, 2023.

“The Arizona Wildcats are headed to the Alamo Bowl to face Oklahoma in San Antonio on Dec. 28th! [football emoji] Find all of the game details on tickets, travel, entertainment, tailgates and local game watch parties here [heart emoji],” posts the University of Arizona on December 6, 2023, the day Dr. Alareer is murdered in an Israeli airstrike.

“It matters what you call a thing,” writes Solmaz Sharif in the titular poem of Look.33

In October 2023, newscasters, reporters, and people who otherwise don’t seem to care about survivors of assault were excited to talk about rape again. This should not need to be said, but I will say it anyway: rape is always horrible. Always. There are no exceptions.

Also: if you only “believe women” when you’re looking for an excuse to support the systemic murder of Brown people, your stance is not one that supports women but one that supports white supremacy.

Since I began writing this in December 2023, international conversations about sexual assault, the IOF, and Palestine have shifted and (re)emerged, with one thing remaining abundantly clear: the IOF systemically uses rape as a weapon against people of all genders in Palestine.

Men—beloved fathers, uncles, brothers, and sons—are being tortured and murdered through rape by the IOF. These men and boys are kidnapped and held without trial, without formal charges, without any cause other than the fact that they are Palestinian. At Sde Teiman, an IOF concentration camp where nearly thirty Palestinians have been murdered as of July 31, 2024, horrific accounts detail how the IOF uses rape as torture—not to get information from prisoners, which, by the way, is also illegal, but “as a form of eternal punishment to show who is supreme.”34

Palestinian men and boys deserve safety. Palestinian people deserve safety. To allow your empathy for those who experience sexual assault to end with white women is to spit in the face of survivors everywhere. To ignore the IOF’s use of rape as a weapon against innocent Palestinians is to reject your claim to humanity. “Every sixty-eight seconds an American is raped”35—and yet, among the people who claim sexual violence as an excuse to murder innocent Palestinians, I have not seen previous or pressing interest in helping survivors of sexual assault.36 This is not a comment on survivors. This is a comment on weaponizing pain, on racialized violence.

Besides the fact that, statistically, they tend to be white, one thing I’ve noticed about rapists and racists is that they’re more afraid of being called what they are than being what they are.37 It matters what you call a thing. It matters what you don’t call it. It matters if a thing exists and is actively causing harm, and no one is calling it what it is.

Here is a list of things that matter:

–In the US, the average lifetime cost of rape is $122,461 per survivor.38

–A male college athlete rapes someone every eighteen days.39

–The University of Arizona’s athletics budget is $100 million.40

–More than 600 people are killed by police every year in the US.41

–Tucson’s overall police budget is $193,274,430.42

–In 2019, a secret Facebook group was leaked. In it, Border Patrol agents made fun of dead migrants, among other abhorrent things.43

–Also in 2019, President Robbins invited Border Patrol agents to UA to attend a career fair and to speak to an undergraduate criminal justice club.44

I lay my head down on my desk. From this angle I can see the gum someone stuck under the whiteboard’s eraser holder that holds no erasers. The gum has been well chewed, fully drained of color. Pink, probably, it was before; I imagine it to be before. On Instagram I see people I know to be abusers posting their recent vacation, sharing photos of their new baby, laughing with their friends.

“It is brave to witness and to not look away,” writes the Palestinian poet and scholar Mosab Abu Toha.45 Even if I wanted to, there is nowhere left to look.

5. “EMERGENCY PROCEDURES” poster; laminated; in corner of room near door; white paper with black writing; red, white, and blue “A” sticker someone has placed in top left corner; text too small to read aside from “CALL or TEXT 9-1-1”

On my first day of training to be a TA, someone asks if a grad student has ever gotten fired. A senior professor in the writing program tells us the story of the girl from years ago who didn’t get fired despite “doing her worst.” What was her worst? She tried to pull down the American flag in her classroom and students complained about it.

Whenever I see the word EMERGENCY I think: “I wake up & it breaks my heart.”46

In my inbox, an email from a “reporter” asking if I’d like to comment on being called antisemitic by a popular Zionist account for reposting anti-genocide content.

Whenever I see the word PROCEDURES I hear TRAINING and I think: “Solmaz, have you thanked your executioner today?”47

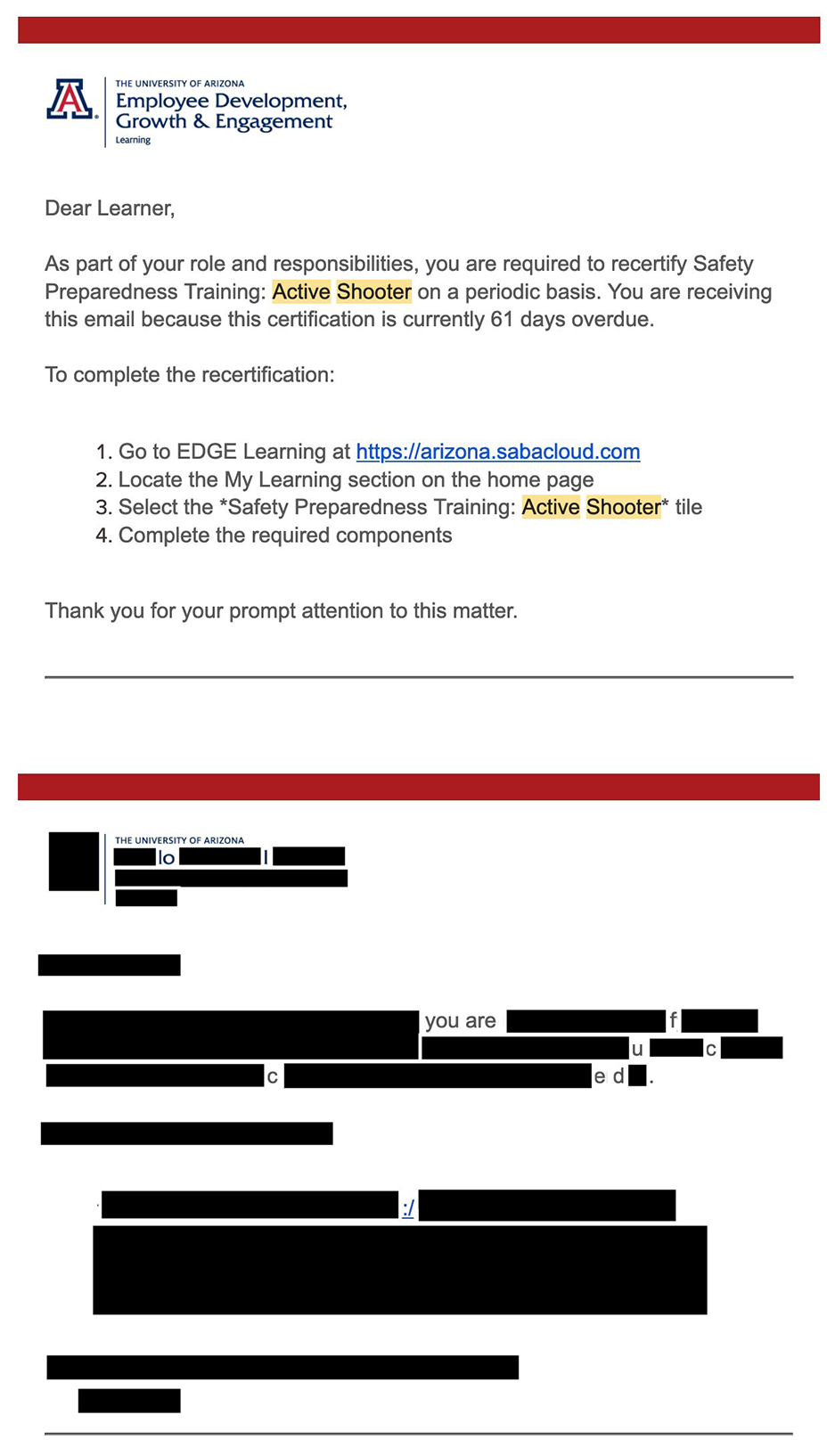

In my inbox, an email reminder to complete my overdue Active Shooter Training.

A few months after my first day of TA training, on October 5, 2022, a man walked onto campus, into a university building like this one, and shot his former professor Thomas Meixner to death.

Like me, Tom Meixner grew up playing in streams and rivers in Maryland. He graduated from the University of Maryland, College Park—less than two miles from where I grew up—with a degree in history of science and soil and water conservation in 1992, the year I was born. He was the head of the University of Arizona’s Department of Hydrology, “noted for his work on the water quality of desert rivers,” and loved by his students, family, and friends.48 He also alerted the university he was in danger.

“I knew he was going to try to kill me,” said Professor Christopher Castro, Dr. Meixner’s colleague, who would’ve also been in the hallway that day had he not been out of town.49 Both professors detailed threatening and aggressive behavior, messages, and emails from their former student to UA police. The university knew about this. They failed to protect their community. Our community. “The school failed. I want to know why they failed,” says Professor Castro.50

I see EMERGENCY and I think, “Hand on my heart. Hand on my stupid heart.”51

I see TRAINING and I think, “Studies suggest it’s best not to mention problem in front of power even to say there is none.”52

I think: Professor Tom Meixner was murdered on campus, and his family will never stop grieving. I think: Professor Meixner reported that he was in danger and no one listened to him.

I think: When you CALL or TEXT 9-1-1 how long is the silence until they arrive? I think: How loud is their arrival?

6. Purell wall dispenser; empty

On the main desk by the computer is an empty box of surgical masks with “PLEASE ONLY TAKE 1” written in Sharpie. A shell of a considerate gesture. An abandoned performance.

An F-15 zooms overhead and leaves a tornado of sound in its wake. When they fly over while I’m teaching, we pause our lesson to wait for enough silence to continue. Now, alone in the classroom, I try to use the wave of noise as practice. A reminder to pause before coming back for breath.

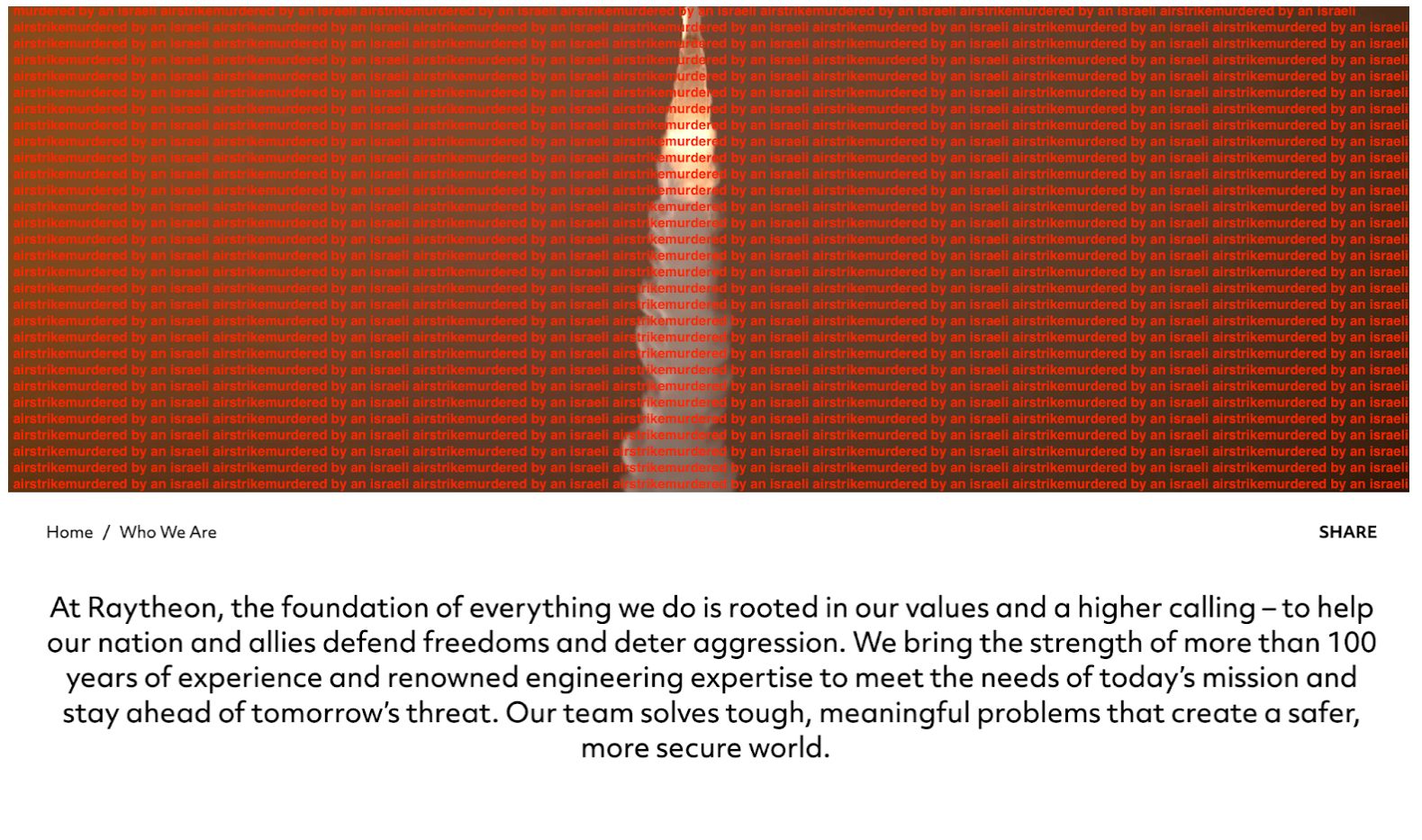

At the Tucson Festival of Books, I hear a bunch of children squealing and laughing. As I move closer, I realize they’re coloring, delighting in adults recognizing their art for what it is: portraits of turtles, unicorns, a helicopter. Above them, the name of the tent that made this all possible: RAYTHEON. (The “Missiles & Defense” part of their name has been left off the banner.)

I scroll through the Martyrs of Gaza Twitter page. I see Sadeem, nineteen, who was studying interior design and who was her parents’ only daughter. Hamada, twenty-two, a young tailor and student who was soon to graduate Al-Quds University, whose whole family was in the room with him. Samer, Bilal, Nidal, Ibrahim, Luna, Fatima, Batoul, Misek, Anas and Ahmad, Saeed, Alaa, Abdulaziz, Ulaa, Mu’min. Anas. Baby Carmel. Walaa. Heba. I see their faces. They are alive and smiling.

The words above them:

murdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrikemurdered by an israeli airstrike

What does it mean when we can hear the planes alerting us of their looming presence overhead? When they are above us, we know where they are. When they are above us, we remember how materially they exist. By the time we hear them, they are already gone.

7. Two windows; one a long rectangle; one a square; both locked and shut; a smiley face written in dust on the bottom left panel of the rectangular pane

On the wall opposite the windows, a digital clock reads 11:14 am next to a broken analog clock that two out of the nineteen students in this room know how to read. This isn’t their fault. Do you need to know how to read an analog clock now anyway? I’m more concerned that they know to call a genocide a genocide when it is unfolding before their eyes.

This classroom is on the third floor. Both windows are on the same wall of the brick building. A tree—a pine maybe—is too far away from the window to reach from the classroom, even the branches too far to grip onto if I needed to jump and hold onto something. If anyone did.

There is no time, no space, no silence to grieve in Palestine. Every war plane that flies over the classroom is a reminder of the University of Arizona’s loyal and historic relationship with Caterpillar, with Raytheon. Of our relationship with murder.

Refaat Alareer’s poem “If I Must Die” is seen thirty-two million times on Dr. Alareer’s personal Twitter account alone.53 Concrete fully covers the pine’s roots three floors below. Concrete covers the dirt, the grass that the university never fails to keep green in this desert.

“We didn’t just lose Alareer, but we lost his poetry; it’s all underneath the rubble, all the future poetry he would have written. And all these artists who have been killed… what’s happened to their art? We talk about numbers of people dead, and we can’t even begin to comprehend this other loss,” says the Palestinian poet Najwan Darwish.54

An email in my inbox says my active shooter training is still overdue and even though I’m only teaching online, it must be done immediately.

On October 23, 2003, the Palestinian journalist Bayan Abusultan writes from Gaza: “40 Palestinian women are in israeli prisons with no hopes of ever seeing light again.”55

On October 23, 2023, I receive an email from Arizona Athletics advertising UA’s upcoming football game against Oregon State. The subject line reads: “Me, Standing Next to the Speaker: Plays our Fight Song.”

On October 24, 2023, the acclaimed writer Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah goes on The Daily Show and speaks about the commodification of racialized violence. “I think that in our consumer culture where we have this idea that people’s bodies are something for us to be entertained by, we’ve gotten really comfortable just viewing humans as a means to an end,” he says. “I think the NFL is particularly heinous. I think that it’s the big juggernaut of evil white men telling Black bodies ‘go hurt yourself’... I think that paradigm exists in a lot of other places too.”56

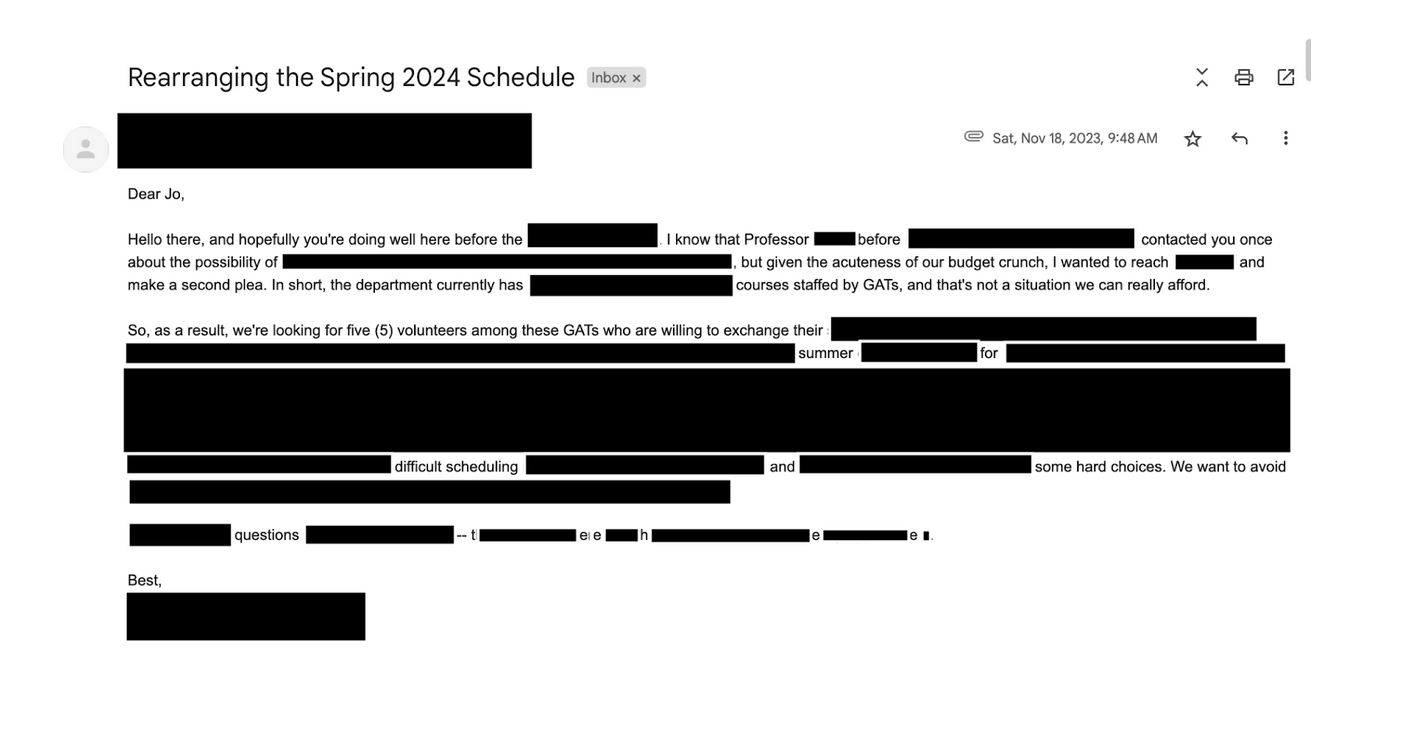

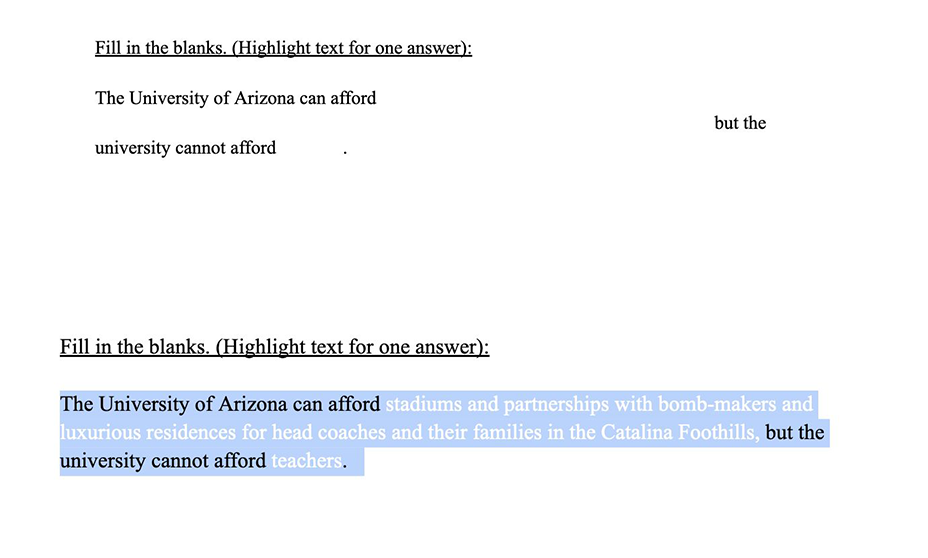

An email in my inbox asks if I’d like to volunteer to give up teaching creative writing next year because of budget cuts. A simple Google search tells me the University of Arizona football coach, Brent Brennan, is a white man whose contract guarantees him $17.5 million over five years as head coach of the Wildcats.57 Despite ongoing budget cuts, in February 2024, UA also hires athletic director Desireé Reed-Francois with an annual base salary of $1 million.58

I look around this empty classroom. The eraserless dry-erase board; the empty Purell dispenser; the empty box of face masks; the laminated posters that alert me to impending danger; the closed door; the windows I cannot open.

Safety, education, human rights—where do these values show up in a University of Arizona classroom? In this case, it is in the absences—the old textbook, the dried-up marker, the unreadable print of safety procedures, the smudged windows—that the truth announces itself.

Three floors below, the sprinklers click on, startling the doves, disturbing their rest. The clicking gets faster, louder. It puts into motion what was at rest. The broken clock above me is silent while the concrete three floors below darkens. On the sidewalk, water spreads outward. It thickens like blood pooling from an open wound.

-

National Sexual Violence Resource Center, “Statistics about Sexual Violence,” 2015, link. ↩

-

“Campus Sexual Violence: Statistics,” RAINN, June 7, 2016, link. ↩

-

Rawan Damen, dir., Al Nakba, Palestine Remix, Al Jazeera, 2008 and 2013, link. ↩

-

Campaign Zero, “Mapping Police Violence,” last updated September 3, 2024, link. ↩

-

Police Scorecard, “Tucson Police Department,” March 30, 2021, link. ↩

-

Jennifer L. Truman and Rachel E. Morgan, “Violent Victimization by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, 2017–2020,” Department of Justice, 2022, link. ↩

-

Cato Institute, “National Police Misconduct Reporting Project,” 2010, link. From the same study: “While the rate of police officers officially charged with murder is only 1.06 percent higher than the current general population murder rate, if excessive force complaints involving fatalities were prosecuted as murder the murder rate for law enforcement officers would exceed the general population murder rate by 472 percent” (4). This study’s failing is its lack of examination of race in these statistics. From other studies, we know that racialized people (particularly Black and Indigenous people) are disproportionately murdered by police. ↩

-

Defenders of Wildlife, “Climate Change and the Sonoran Desert Region,” 2010, link. ↩

-

John P. Schmal, “Tracing Your Indigenous Roots in Sonora: A Challenge and an Adventure,” September 16, 2019, link. ↩

-

Kevin Cooney, “Weaponizing the Desert at the US–Mexico Border,” Edge Effects, February 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

For more on the militarization of the border and its effects on the Tohono O’odham Nation, see Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik, “‘Persistent Surveillance’: Militarized Infrastructure on the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Avery Review (May 2019), link. ↩

-

“Celebrating Tucson (S-cuk Son),” Archaeology Southwest, August 20, 2019, link. ↩

-

In La Calle, Dr. Lydia R. Otero writes about Tucson’s urban renewal projects that targeted areas densely populated by Black, Mexican American, and Chinese American families. “The city destroyed 80 acres,” she says in an interview with C-SPAN, discussing how the city of Tucson claimed houses were like “slums” to justify their destruction. But if that were even true, wouldn’t it have been the city’s responsibility to provide services? “It’s almost like the city intentionally deprived areas of service in order to justify its demolition,” Dr. Otero says. See “La Calle,” C-SPAN, September 5, 2016, link, La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010). ↩

-

Brad Lancaster, “Sentinel Peak/A-Mountain: A View of How the Santa Cruz River and Tucson Basin Ecology/Hydrology Is Changing,” Harvesting Rainwater, April 7, 2023, link. ↩

-

Environmental and General Services, “A-Mountain Landfill,” City of Tucson, July 20, 2022, link. ↩

-

Nicole Ludden, “Tohono O’odham to Receive Ancestral Land Near Tucson’s ‘A’ Mountain,” tucson.com, last updated June 3, 2024, link. ↩

-

Ludden, “Tohono O’odham to Receive Ancestral Land Near Tucson’s ‘A’ Mountain.” ↩

-

Katie Burkholder, “Ancestral Lands to Be Returned from the City of Tucson to Tohono O’odham Nation,” News 4 Tucson, last updated May 19, 2023, link. ↩

-

“About Caterpillar,” Caterpillar, last updated March 9, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Caterpillar Inc's Role in Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories,” Amnesty International (blog), December 23, 2010, link. ↩

-

“Mining 360 Program: CAT Employees Become UA Wildcats,” University of Arizona College of Engineering: Mining and Geological Engineering, August 30, 2019, link ↩

-

For more, see Taylor Miller, “A Pause, On Possibility,” Avery Review (December 2023), link. ↩

-

“A Mountain, or Sentinel Peak,” Pima County Public Library, last updated August 7, 2024, link. ↩

-

Frank S. Crosswhite, “The Annual Saguaro Harvest and Crop Cycle of the Papago, with Reference to Ecology and Symbolism,” Desert Plants 2, no. 1 (1980): 3–61. ↩

-

James Baldwin, in I Am Not Your Negro, also says, “I attest to this: the world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.” See Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, comp. and ed. Raoul Peck (New York: Vintage, 2017), 107. ↩

-

SJP at UArizona (@sjpuarizona), “ACTIONS THIS WEEK,” Instagram, October 9, 2023, link. ↩

-

“University of Arizona International Student Report,” College Factual, April 22, 2017, link. ↩

-

“Arizona Basketball Summer Tour Features Stops in Israel, Abu Dhabi,” Men’s Basketball, Arizona Wildcats, August 8, 2023, link. ↩

-

Shoshanna Solomon, “Ben-Gurion University Signs Research Deals with Arizona, Mexico Counterparts,” Times of Israel, September 17, 2024, link. ↩

-

SJP at UArizona (@sjparizona), “For immediate release,” carousel of four images, Instagram, October 12, 2023, link. ↩

-

Solmaz Sharif, “Look,” in Look (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2016), 3. ↩

-

Diana Buttu, “Rioting for the Right to Rape Palestinians,” Zeteo, July 31, 2024, link. See also, Amy Goodman, host, “Israel’s Torture and Rape of Palestinian Prisoners Defended by Knesset Members, Far-Right Mobs,” Democracy Now, August 1, 2024, link. ↩

-

Sophia Salyers, “College Athletes as Defendants in Rape Trials: The Impact on Legal Decision-Making” (bachelor’s thesis, University of Kentucky, 2023), 3, link. ↩

-

Rape is about power. Systems of patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, and militarization uphold its use. As such, it is used as a tactic of war, a weapon used to oppress, dehumanize, and erase. Its use by the IOF against Palestinians—men, women, and children—is extensively documented. For more about its sexual assault of men and boys, see Ira Memaj, “The Gaza Crisis We’re Not Talking About,” Nation, May 13, 2024, link. In short, even if these people who claim to care about sexual assault actually cared about sexual assault, the way to go about helping survivors is decidedly not genocide but rather working to dismantle these systems of oppression that use rape and sexual violence as tools. ↩

-

“Perpetrators of Sexual Violence: Statistics,” RAINN, April 13, 2021, link. ↩

-

Cora Peterson et al., “Lifetime Economic Burden of Rape Among US Adults,” American Journal of Preventative Medicine 52, no. 6 (June 2017): 691–701, link. ↩

-

C. Johnson, “When Sex Is the Issue,” US News & World Report 111 (1991), 34–36. ↩

-

Mike McDaniel, “University of Arizona Considers Cutting Sports Teams amid $240M Shortage,” Sports Illustrated, November 10, 2023, link. ↩

-

Also, despite making up 6.1 percent of the US population, 24.9 percent of people murdered by police officers are Black men. See “US Data on Police Shootings and Violence,” University of Illinois Chicago Law Enforcement Epidemiology Project, January 21, 2021, link. After excessive force, sexual violence is the second most reported form of police misconduct. See Cato Institute, “National Police Misconduct Reporting Project,” 1. ↩

-

Vera Institute of Justice, “Tucson, AZ,” What Policing Costs: A Look at Spending in America’s Biggest Cities, June 29, 2020, link. ↩

-

Ryan Devereaux, “Border Patrol Agents Tried to Delete Racist and Obscene Facebook Posts. We Archived Them,” The Intercept, July 5, 2019, link. ↩

-

Elizabeth Oglesby, “Universities Should Regulate the Border Patrol on Campus,” The Hill, April 13, 2019, link. ↩

-

Mosab Abu Toha (@mosab_abutoha), “It is brave to witness and to not look away,” Instagram, March 23, 2024, link. ↩

-

Cameron Awkward Rich, “Meditations in an Emergency,” Split This Rock, January 21, 2020, link. ↩

-

Saeed Jones, “Poem: ‘Social Skills Training’ by Solmaz Sharif,” Buzzfeed, June 23, 2016, link. ↩

-

Dylan Smith and Paul Ingram, “UA Profs Felt Like ‘Sitting Ducks’ as They Pleaded for Help before Meixner Killing,” Tucson Sentinel, October 13, 2022, link. ↩

-

Smith and Ingram, “UA Profs Felt Like ‘Sitting Ducks.’” ↩

-

Smith and Ingram, “UA Profs Felt Like ‘Sitting Ducks.’” ↩

-

Rich, “Meditations in an Emergency.” ↩

-

Jones, “Poem: ‘Social Skills Training’ by Solmaz Sharif.” ↩

-

Refaat in Gaza (@itranslate123), “If I must die, let it be a tale,” Twitter, November 1, 2023, link. ↩

-

Alexia Underwood, “Palestinian Poet Najwan Darwish: ‘We Can’t Begin to Comprehend the Loss of Art,’” Guardian, January 4, 2024, link. ↩

-

Bayan (@bayanpalestine), “Need I remind you that while Palestinian freedom fighters released five women who were held captives in #Gaza the past couple of weeks, 40 Palestinian women are in israeli prisons with no hopes of ever seeing light again,” Twitter, October 23, 2023, link. ↩

-

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, “‘We’ve gotten really comfortable viewing humans as a means to an end,’” The Daily Show (@thedailyshow), Twitter, October 25, 2023, link. ↩

-

Justin Spears, “Arizona, New Head Football Coach Brent Brennan Ink 5-Year, $17.5 Million Contract,” tucson.com, last updated January 22, 2024, link ↩

-

Justin Spears, “U of A Hires Desireé Reed-Francois as Next Athletic Director,” tucson.com, last updated February 24, 2024, link. ↩

Jo Blair Cipriano is the winner of an Academy of American Poets Prize, two University of Arizona MFA Creative Writing Awards, and has received support from Tin House, the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, and Brooklyn Poets. A former college dropout, Jo was a 2024 Writer-In-Residence at the Hemingway House, and is now an MFA candidate at the University of Arizona where they are a Southwest Field Studies in Writing fellow.