The people, they won’t leave

What is threatenin’ about divesting and wantin’ peace?

The problem isn’t the protests, it’s what they’re protesting

It goes against what our country is funding

(Hey) Block the barricade until Palestine is free

(Hey) Block the barricade until Palestine is free…

Actors in badges protecting property

And a system that was designed by white supremacy

—Macklemore, “Hind’s Hall,” May 7, 20241

On the evening of May 3, 2024, the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) hosted a dinner, presided over by the university’s president, Santa Ono, and three of the eight members of the university’s Board of Regents, to celebrate the recipients of honorary degrees. A few hundred feet away, at the center of the university’s campus, around 100 students were encamped to protest the university’s unwillingness to divest from companies involved in the colonization of Palestine and genocide in Gaza. For four weeks, protesting students demanded meetings with President Ono and university regents, but these demands were ignored. When the dinner took place, then, the Tahrir Coalition, a collective of 90 student organizations at the university working for Palestinian liberation, called for an emergency rally at the art museum.

Several hundred students, accompanied by some staff and faculty, lined the museum’s perimeter and called on the president and regents to meet with them. In response, the administration called in the university’s Department of Public Safety, Ann Arbor Police Department, and Michigan State Police. After unsuccessfully ordering protesters to leave, police officers used pepper spray and physical violence to enforce compliance as some dinner guests looked on. The police also confiscated Palestinian flags, megaphones, drums, and a laptop from protesting students.2 These actions, including the theft of student property, are consistent with colonial histories in which the university is understood, advanced, and defended as property. As Robert Nichols writes, property relations are the product of theft—the colonial theft of Indigenous land from Indigenous people.3 This theft of property occurs at many scales, on many levels, with various degrees of force. Universities continue to rely on theft, under the guise of preservation, as a means of property acquisition. Founded and functioning on stolen Indigenous land, many universities are now confiscating items from student protesters as they defend themselves against protests and attempt to manage how those protests will be narrated and remembered.4

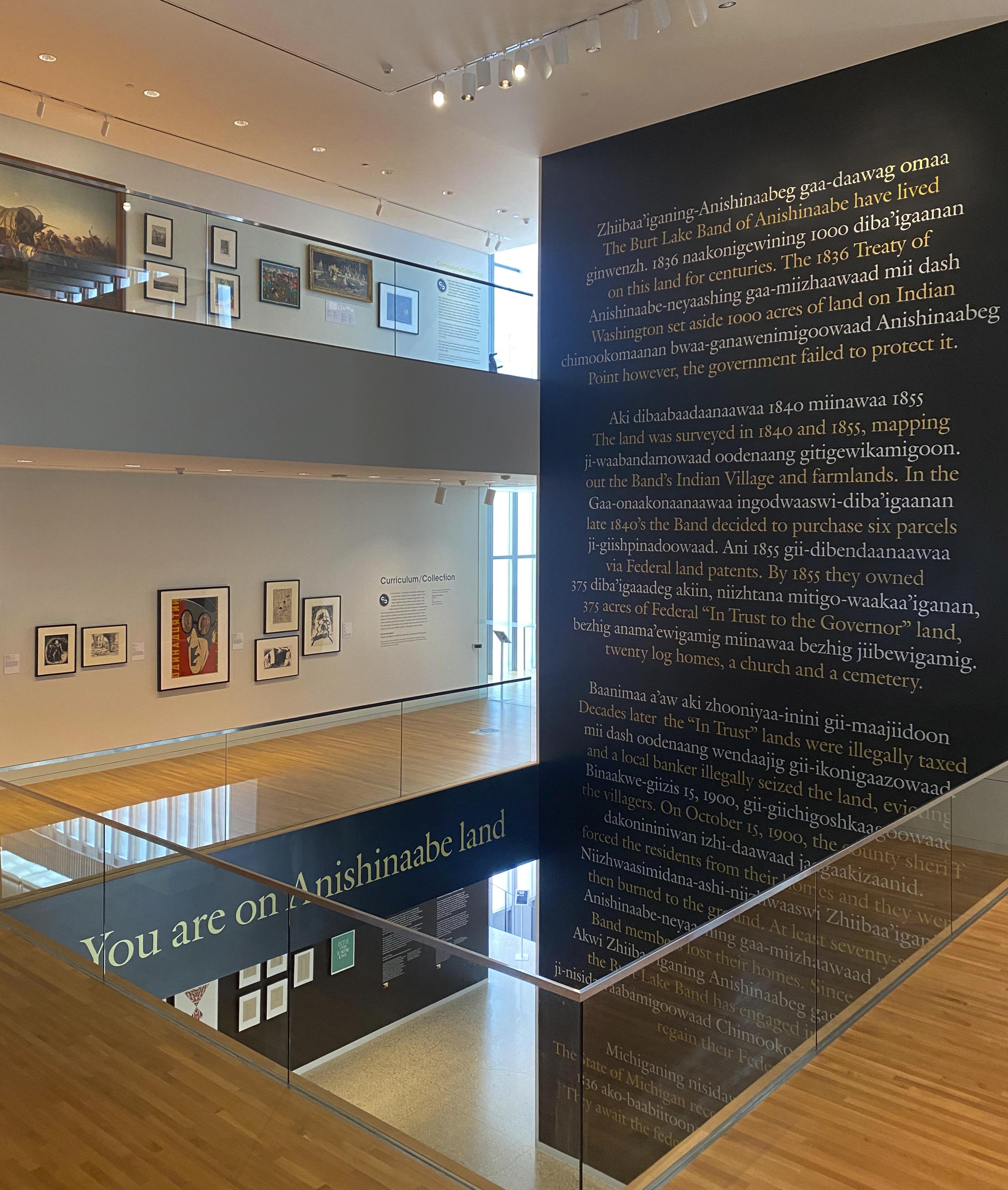

Even as the University of Michigan created a militarized zone around its art museum, the walls of the museum’s spacious atrium featured a large sign proclaiming, in both English and Anishinaabemowin, “You are on Anishinaabe land.” Part of Future Cache, an exhibition by the Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson, the sign denotes that the University of Michigan occupies the homelands of the Anishinaabe people.5 Carlson’s exhibition centers on one of the university’s most recent property acquisitions—a parcel of land on Burt Lake, in the far north of Michigan’s lower peninsula. Opposite the sign, a 40-foot-high memorial wall narrates the passage of this parcel from Anishinaabe land into colonial property via the burning of the Burt Lake Band’s village on the site by a local sheriff and his officers in 1900. The university does not simply occupy the land of the Burt Lake Band, Carlson suggests; the university’s occupation of this land is a direct legacy of colonial violence and the continued refusal of state and federal governments to reckon with this violence.

The prominence of Carlson’s sign in the museum emphasizes how the University of Michigan tolerantly accommodates and even celebrates the acknowledgment of the colonial occupation of Indigenous land. Thus, even as Carlson’s exhibition raises troubling questions about the university’s relationship to Anishinaabe land and people, the university provides a place for those questions, albeit only within the liberal framework of recognition and academic freedom.6 It remains to be seen whether Carlson’s exhibition will prompt the university to undertake reparative actions in response to its involvement in the history of stolen Indigenous land.7 In the meantime, the exhibition itself exists as a response—an indication that the university is in some way negotiating issues around its colonial legacy. Last year, President Ono accepted an invitation to the opening reception for Carlson’s exhibition at the art museum.

The University of Michigan’s simultaneous affirmation of statements about US colonialism on land claimed as national territory and violent response to protests against the US’s central role in settler colonialism in Palestine is not exceptional. This hypocrisy or double standard of universities across the United States has come to be known as the Palestine Exception.8 The practice of acknowledging the colonization of Indigenous land emerged in response to demands by Indigenous people in the 1970s, originally in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Land acknowledgments became unofficially institutionalized in Canada after the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was released in 2015. In the United States, institutions like universities and museums increasingly acknowledge that they occupy colonized land, and these acknowledgments skyrocketed after the 2020 summer of racial reckoning in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis.9

The land acknowledgment is now commonplace in universities across the US, even considered a box-ticking exercise on their part as it is sublimated on websites and in introductions to events, lectures, symposia, and other public occasions.10 Many of the universities with their own land acknowledgments, however, vehemently refuse to discuss their integral role in the military-industrial complex that supports the settler colonial occupation of Palestine and genocide in Gaza.11 What, then, should we make of these land acknowledgments? What can we learn about the contemporary US university by examining its unwillingness to connect across colonial land struggles? And how should we understand the university’s acknowledgment of colonial land dispossession in some contexts and its denial in others?

Universities have responded to these sorts of questions by evading them, if not actively suppressing them. The institutional reactions to student protests against settler colonialism and the continued genocide in Palestine have thus attended not to the political, historical, and ethical cases for divestment that the protests are advancing but to the “disruptions” they claim are caused by these protests—the pitched tents, rallies, building occupations, and slogans. And so, at Columbia University, according to former president Minouche Shafik, student protesters were violently removed and arrested on two separate occasions because they “interfered with the operation of the University, refused to identify themselves, refused to disperse, set up tents on campus space, failed to comply with policies, and damaged campus property.”12 At the University of Virginia, according to President Jim Ryan, an encampment of student protesters had to be destroyed by the police because the encampment violated “a long-standing prohibition on erecting tents absent a permit.”13 At the University of California San Diego, Chancellor Pradeep Khosla justified the violent removal of student protesters because “several tents on the grass adjacent to Library Walk” were “in violation of campus policy, which prohibits unauthorized encampments.”14 At Harvard University, according to Interim President Alan M. Garber, “we continue to hear reports of students whose ability to sleep, study, and move freely about the campus has been disrupted by the actions of the protesters.”15 Princeton University’s president Christopher Eisgruber stated that “camping in vehicles, tents, or other structures is not permitted on campus,” even as multiple large white tents were erected to accommodate the hundreds of alumni who would descend onto the campus for its annual reunion.16

But universities invoking “disruption” as pretext to shut down student protests manifest the very politics of land that these invocations are intended to evade. The extended vocabulary of disruption becomes legally and politically actionable because disruptions are treated as a violation of private property. These messages and renderings are powerful because, in liberal modes of thinking, property is a self-evident category with unquestioned universality. Property rights must therefore be defended. On this basis, universities have quickly narrativized disruption of campus life or lack of safety, just as they have employed the rhetoric of discomfort and unsafe environments created by student activism around Palestine; policing and carceral tactics have become “responses” to manage these disruptions. Perhaps most consequentially, universities have also instituted what should be understood as disruptions of student life as punitive measures directed at “disruptive” students: threatened and actual suspensions, evictions of students from campus housing, and other forms of punishment. These disciplinary actions are not just particularly harmful and onerous for low-income and international students, whose ability to remain in the university or the US altogether remains under threat, but for all protesting students for whom the neoliberal university is simultaneously landlord, stipend and tuition provider, and visa sponsor. Student protesters recognize the precarity of their position, and yet they see the inconceivable and ever-present occupation and destruction of Palestine. Encampment speeches, calls, and statements also evidence an awareness of Zionist occupation and anti-Zionist protest as connected to long histories of Indigenous dispossession and resistance across North America.17

Liberal notions of property as a possession obscure the web of social and power relations that must be performed and enacted to produce property as legitimate in the first place. Indeed, as Brenna Bhandar outlines in Colonial Lives of Property, modern property law developed with and through the colonial seizure of Indigenous land in Australia and Canada, as well as in Israel/Palestine.18 The subsequent history of property as an exchange commodity (a fictitious commodity, as Karl Polanyi describes) shows how ownership is secured not just through so-called legal interventions and devices like market, survey, register, price, and deed, but is also continually defended through “extralegal” tools like violence, corruption, looting, and fraud.19 As is well known, police forces in the United States originated in the long history of slave patrols who secured property in the colonial era.20 The contemporary presence of police on campus to manage so-called disruptions brings the history of maintaining property ownership by violence into sharp focus.21 More generally, approaching land as property and now as real estate through a series of historical periods reveals that the history of land ownership is far from fixed. In the case of the US university, this approach reveals a set of relations for exchange continuously deployed to defend the university as private property, with no distinction between private and so-called public schools.

Settler colonialism historically proceeds through a repertoire of legal and extralegal devices and rationales to seize Indigenous land and maintain sovereignty over it. Anglo and European notions of civilization erased prior collective relationships to land, rendering it terra nullius—belonging to no one. Treating Palestine as “empty” has similarly provided a basis for the Zionist fantasy of “making the desert bloom,”22 a myth sustained even as Palestinian olive groves and crops are burned and the Palestinian people are dispossessed by Israeli settlers. To expropriate land, the Israeli state relies on legal and extralegal actions that include military deployment and surveillance technologies that US university endowments invest in and profit from.23 They also require land-use planning, criminal laws, and outright urbicide, as we see with proposals to remodel and settle Gaza with beachside condos as the genocide nears a full year.24 Many of these actions were first deployed in the course of US colonization, which included coerced treaties with Indigenous people, refusal on the part of the US government to honor its treaty obligations, differential rights to property and citizenship between Indigenous people and settlers, and sanctioned settler violence against Indigenous people.

The history of the settler-colonial university is one of land possession secured through genocidal acts of violence—laying bare the willingness of universities to acknowledge land theft in the United States and the simultaneous refusal to acknowledge their complicity in such theft in Palestine. Rather, each response protects property and prevents reparative justice to historical and continued land theft, plunder, and destruction, while also discouraging new solidarities that advance claims for justice.

This is certainly the case at the University of Michigan. The university’s three campuses are not only located on Indigenous land ceded in the 1807 Treaty of Detroit; the university’s very founding was inspired by, if not constituted by, a grant of land made by representatives of the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi people in the 1817 Treaty of Fort Meigs to support an institution where their children could be educated.25 The University of Michigan was chartered in 1821 in large part to claim the 1817 Anishinaabe land grant and place it under the control of the university’s Board of Trustees. Instead of using the grant to support the education of the Michigan Territory’s Anishinaabe people, however, the Board of Trustees used it to further dispossess the Anishinaabe population, advancing the colonial settlement of the territory on the course to eventual statehood.

Until recently, the 1817 Anishinaabe land grant was remembered in the university’s history as a land gift from willing benefactors; the land grant has now been recast as a surrender of land forced upon unwilling victims of colonialism. And yet, whether the university remembers a land gift or a land theft, it fails to account for the Anishinaabe agency and intention behind the 1817 land grant, the university’s treaty-based obligation to educate Michigan’s Anishinaabe people, and the Anishinaabe dimensions of the university’s history, land, and wealth.26

In typical formulations, land acknowledgments protect property by rendering the Indigenous people who were dispossessed and displaced by colonialism as “custodians,” “caretakers,” and “stewards” of the land, rather than as the land’s rightful occupants. They present Indigenous land as “traditional homeland” rather than territory that has been seized and settled. In so doing, they frame the colonial seizure of Indigenous land as a historical event rather than the object of contemporary political struggle. The university land acknowledgment thus “tacitly affirms the putative right of non-Indigenous people to now claim title.”27 In other words, universities acknowledge Indigenous claims to the land as part of their refusal to rematriate Indigenous land that they now own and occupy. The anti-politics of these land acknowledgments makes them far more pernicious to struggles for land than merely performative liberal gestures, as they are often categorized.

The refusal to respond adequately to the racial settler colonial project of the United States runs parallel to the repudiation of Israel as a settler colonial project. Indeed, typical land acknowledgments are based upon and continue the colonial bestowal of proprietary interests on Indigenous people only under conditions that require those interests to be alienated to the US government. They are thus premised on the absence of Indigenous people on their homelands, the nullification of Indigenous proprietary interests in those homelands, and the invalidation of Indigenous claims to “original ownership”—not dissimilar to nonrecognition of Palestinian deeds or Bedouin stewardship and cultivation that Zionists employ to justify settlement.28

Under racial capitalism, either prior possession of the land must be claimed in a recognizable propertied form—thus universalizing and backdating a general possessive logic as the normative benchmark—or this possession is disavowed, undercutting the force of a subsequent claim of dispossession.29 The presence of Indigenous ancestors, as so-called remains, in many university museums and archives further corroborates the colonial interruption of Indigenous presence and sovereignty on Indigenous homelands. Both spatially and temporally, these political inheritances are multifaceted, fragmented, and defy the linear, “progressive,” and seamless time of a liberal politics of acknowledgment, which seeks to foreclose decolonization as the contemporary struggle for Land Back and the radical redistribution of resources.

When considered as anti-political attempts to protect colonized land as property, land acknowledgments are conterminous with militarized shutdowns of campus-based encampments and building occupations by students protesting university complicity in the colonization of Palestine and genocide in Gaza. Each aims to protect the sanctity of universal property rights: both the physical properties of university campuses and the financial properties of university endowments. Each reveals that the university, as property, must be defended.

It is this reflexive defense of property that student protesters are rightly targeting in their demands; their protests and occupations not only pry open campus spaces and buildings that the university claims as its property but leverage claims on inaccessible property—university endowments and investments in arms and weapons manufacturing that profit from genocide. In so doing, students have rendered campuses as fronts in political struggles around the control, purpose, and significance of university endowments that borrow and develop on a long history of anti-colonial internationalist solidarity among Indigenous peoples and other colonized subjects. Expressions of solidarity with Palestinians by racialized settlers and Indigenous people temporalize and spatialize colonial violence as a present condition. The anti-colonial ambitions of student protesters cut across Indigenous peoples, Palestinians, and Third World movements. Drawing on thinkers, activists, and theorists, the encampments stand in opposition to the liberal racial order that seeks to commodify and depoliticize resistance movements just as it seeks to do with land acknowledgments.

Student protests against university complicity and participation in the colonization of Palestine and genocide in Gaza, then, also suggest a re-centering of university policies on land acknowledgments; these acknowledgments should no longer serve as affirmations of the liberal-settler frameworks of racial difference and reconciliation but rather as resistance to contemporary forms of imperialism, colonialism, and oppression toward a future of radical redistribution. The protests, in other words, activate new social, ideological, and political imaginaries that reassert the principle on which land acknowledgment policies can prefigure a politics of decolonization—no justice on stolen land. As the TAHRIR Coalition put it: “We demand transparency and accountability from our administration, and a shift in resource allocation of resources for Humanity and Reparations. This involves directly supporting those impacted by the legacy of empire, colonialism, and racism, and engaging in efforts that contribute to systemic and meaningful change.”30

Epilogue

At 5 am on the morning of May 21, 2024, the University of Michigan administration deputized the university’s Department of Public Safety and the Michigan State Police to destroy the encampment of students peacefully protesting the university’s complicity in the Gaza genocide. In riot gear, police deployed pepper spray and batons against unarmed students. This militarized force injured many students; at least two undergraduate students ended up in the emergency room. At least three students were arrested. After the destruction of the encampment, the university’s Department of Public Safety apparently requested Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel to file warrants for criminal charges against some of the students involved in the Gaza solidarity protests.31

An hour after the encampment was destroyed, President Ono emailed the university community. According to Ono, the university fire marshal determined that “were a fire to occur, a catastrophic loss of life was likely”; the camp occupants refused to comply with the fire marshal’s safety requests; thus “that forced the university to take action and this morning, we removed the encampment.”²⁵ By invoking a hypothetical and unlikely “catastrophic loss of life,” Ono thereby overwrote the actual and ongoing catastrophic loss of life that the encampment was set up to protest and end. Echoing the messages of other university presidents, Ono mentioned “months of escalating disruptions to university operations”; he also referenced “spray paint graffiti” on a sign outside a university building, paint (that was washable) over the university’s “M” logo on the site where the students were encamped, and the replacement of brick pavers (that were damaged or missing) with concrete at the encampment site. “These actions were not free speech,” Ono wrote, “they were destruction of property.”

According to students at the camp, the university had never communicated any concerns about fire for the month that the camp was in existence; those concerns were simply a convenient pretext to destroy their encampment. Students also mentioned that, if the university was genuinely concerned about fire danger, it easily could have worked with university officials to mitigate that risk. Students did not mention that only a few months earlier, in January, university football fans set at least twenty-one fires across Ann Arbor after the University of Michigan football team won the National Collegiate Football Championship final game, the police announced that the fires were part of “celebrations” that were “fun, responsible, and peaceful,” and no arrests were made or disciplinary actions taken against the many students involved.32

About twelve hours before the encampment was destroyed, a committee called “Honoring Article XVI” met virtually at the University of Michigan. Named after the provision in the 1817 Treaty of Fort Meigs in which Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi people gave land to an institution where their children could be educated, the committee had convened in October 2023 to hold the university accountable to its treaty-based obligations to Michigan’s Indigenous people.33 At the May 2024 meeting, President Ono charged the committee with developing “a detailed five-year proposal that would include actions, strategies, and initiatives to support the success of Native students, staff, faculty on campus, build better partnerships with Native tribal communities, and improve the educational experiences and prospects for Michigan’s Native peoples.”34

President Ono did not charge the committee with looking into the perspectives of Native tribal communities on the student encampment whose destruction he was poised to justify if not order. Some of these communities explicitly endorse the student encampment movement. In a statement released on April 28, 2024, the Five Nation Long House Confederacy announced that, after observing the behavior of Europeans for the last five hundred years, they have seen “systemic colonial genocidal wars upon our Mother Earth and all Original Peoples and our territory here in Turtle Island and abroad, including Palestine.” Based on that history and the Two Row Wampum Peace Treaty—one of the oldest treaties made between Indigenous people and colonists on Turtle Island and, for the Indigenous people who made it, a treaty that still holds—the confederacy then proclaimed, “We grant the full right to those who are occupying McGill (University) and other campuses throughout Turtle Island to be upon the said lands, with the expressed intent of engaging their administrations to divest from the colonial genocide of Israel upon the Palestinian people and from the war machine in general.”35

Land acknowledgments like these can help us imagine alternative political futures.36 They can build new solidarities between anti-colonial and decolonizing liberation movements that otherwise appear distant across both space and time. They can connect institutions and communities to these movements. And they can guide us to see how Indigenous refusals of settler state jurisdiction and Palestinian land struggles against the Israeli state are related. Land acknowledgments like these also reveal the contradiction of universities simultaneously acknowledging the colonized land they occupy and repressing students who protest colonialism in Palestine. Recognizing this contradiction, we can challenge university land acknowledgments that are posed as adequate on their own terms. We can upend land acknowledgments that are routinized as recognitions of past colonial violence. And we can commit to the conjoined Indigenous and Palestinian efforts to resist ongoing settler occupation and advance their attendant principle: no justice on stolen land.

-

Sneha Dhandapani, “Pro-Palestine Protest at UMMA on Commencement Eve Met with Police Force, Detainments, and Arrest,” Michigan Daily, May 6, 2024, link. ↩

-

Robert Nichols, Theft Is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020). ↩

-

On the theft of property from students protesting in support of Palestine liberation, see Columbia University Apartheid Divest, “Columbia University Archive Theft,” July 9, 2024, link. ↩

-

Andrea Carlson, Future Cache, University of Michigan Museum of Art, link. ↩

-

Brenna Bhandar, “A Land Acknowledgment in a Different Key: Palestine, Solidarity and the Disruption of the Liberal Script,” Middle East Critique (July 2024): 1–16. ↩

-

On the University of Michigan’s involvement in the colonial history of Native dispossession, see Andrew Herscher, “Reserved for Indian Purposes,” in Andrea Carlson: Future Cache, ed. Jennifer Friess (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Art, 2024); and Andrew Herscher, Under the Campus, the Land: Anishinaabe Futuring, Colonial Non-Memory, and the Origin of the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming). ↩

-

Bhandar, “A Land Acknowledgment in a Different Key.” ↩

-

In 2016, in response to student petitions, Columbia University erected a plaque “In Honor of the Lenape People.” In the following two years, several other universities adopted land acknowledgments, such as Indiana University, Michigan State University, Northwestern University, and the University of Illinois. For the value and the limits of the settler colonial framework, and especially land acknowledgments, when thinking about Israel/Palestine, see also Lila Abu-Lughod, “Imagining Palestine’s Alter-Natives: Settler Colonialism and Museum Politics,” Critical Inquiry 47, no. 1 (2020). ↩

-

These liberal gestures toward Indigenous recognition and reconciliation between Indigenous and settler communities are themselves controversial in Indigenous studies and activism: see Audra Simpson, “Sovereignty, Sympathy, and Indigeneity,” in Ethnographies of US Empire, eds. Carole McGranahan and John F. Collins (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). For “box ticking,” see Chelsea Vowel, “Beyond Territorial Acknowledgments,” âpihtawikosisân (blog), September 23, 2016, link. ↩

-

In President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address—the speech that made the term “military-industrial complex” famous—the term was originally formulated as “military-industrial-academic complex”: see Henry Giroux, The University in Chains: Confronting the Military-Industrial-Academic Complex (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2007). ↩

-

President Minouche Shafik to Michael Gerber, Deputy Commissioner, Legal Matters, New York Police Department, April 18, 2024, link. ↩

-

“A Message from Chancellor Pradeep K. Khosla,” May 1, 2024, link. ↩

-

Interim President Alan M. Garber to Members of the Harvard Community, May 6, 2024. ↩

-

Christopher L. Eisgruber, “On Encampments, Free Speech, and ‘Time, Place, and Manner’ Rules on University Campuses,” May 28, 2024, link. ↩

-

For example, encamped students at Cornell University stated that “Cornell’s refusal to cut ties to Palestinian genocide reflects its history of profiteering from the violent dispossession of Indigenous Peoples across North America,” and they included the creation of both a Palestinian studies program and Indigenous studies department in their demands: see link. Similarly, the University of Michigan’s TAHRIR Coalition stated, “Our mission is to decolonize our university, acting in solidarity with the victims of the American empire, and those resisting its injustices both locally and globally”: see “About,” TAHRIR Coalition website, link. ↩

-

Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957). ↩

-

Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001). and Ben Brucato, “Policing Race and Racing Police: The Origin of U.S. Police in Slave Patrols,” Social Justice 47, nos. 3/4 (2020). ↩

-

Malini Ranganathan and Anne Bonds, “Racial Regimes of Property: Introduction to the Special Issue,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40, no. 2 (2022). ↩

-

Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property. ↩

-

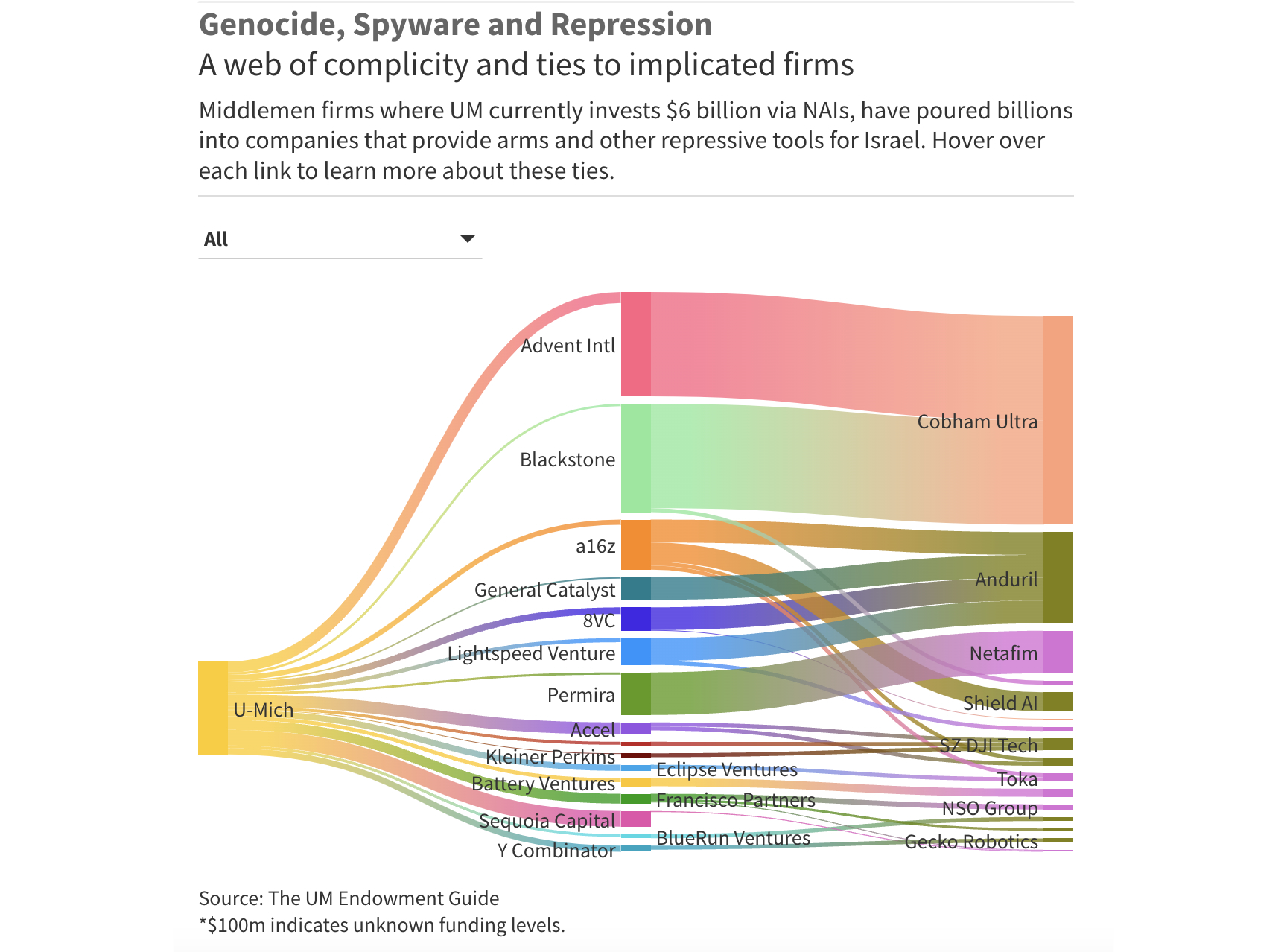

TAHRIR Coalition’s Endowment Guide makes these links visible for the University of Michigan. TAHRIR Coalition, “The University Endowment and the Genocide in Gaza,” link. ↩

-

Orla Guerlin, “Jewish Settlers Set Their Sights on Gaza Beachfront,” BBC, March 24, 2024, link. ↩

-

The Anishinaabe are linguistically, historically, geographically, and culturally related Indigenous people. As Michael A. McDonnell notes, while these people referred to themselves as Anishinaabe, they became known to colonists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries through “tribal” distinctions, such as Ojibwe (Ojibwa, Chippewa), Odawa (Odaawaa, Ottawa), and Potawatomi (Pottawatomi, Pottawatomie, Bodéwami). As Michael Witgen notes, the Anishinaabe historically did not organize themselves according to tribal identity but rather according to clan, band, and village. On the Anishinaabe around the Great Lakes, see Michael A. McDonnell, Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015), and Michael Witgen, An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). ↩

-

See Herscher, Under the Campus, the Land. ↩

-

Michael Lambert, Elisa J. Sobo, and Valerie L. Lambert, “Rethinking Land Acknowledgments,” Anthropology News, December 20, 2021, link. ↩

-

For how older forms of claim and ownership are diminished with the introduction of title by registration, see chapter 2, “Propertied Abstractions,” in Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property. ↩

-

Nichols, Theft Is Property!, 238. ↩

-

TAHRIR Coalition website. ↩

-

Jon King, “Pro-Palestinian Protesters Slam U of M for Asking Michigan AG to Press Charges Against Students,” Michigan Advance, July 1, 2024, link. On September 12, 2024, Attorney General Nessel announced charges against eleven protestors—nine participants in the Gaza solidarity protests and two counter-protestors. Seven of the Gaza solidarity protestors were charged with both the misdemeanor of trespassing and the felony of resisting and obstructing a police officer. See Ava Chatlosh, “Michigan Attorney General Announces Criminal Charges Against 11 Protestors Connected to Gaza Solidarity Encampment,” Michigan Daily, September 12, 2024, link. ↩

-

Mary Ellen Murphy, “Ann Arbor Police: 21 Fires, No Arrests,” WGHN, link. ↩

-

More specifically, the Honoring Article XVI Committee was constituted as part of the university’s “DEI 2.0” strategic planning process to follow through on recommendations previously made by a Native American Student Task Force Committee and an Indigenous Initiatives Leadership Group. ↩

-

Email from University of Michigan Assistant Vice Provost Marie Ting to members of the Honoring Article XVI Committee, May 7, 2024. ↩

-

Five Nation Longhouse Confederacy, “Notice,” April 28, 2024. ↩

-

Abu-Lughod, “Imagining Palestine’s Alter-Natives.” ↩

Andrew Herscher’s work endeavors to bring the study of architecture and urbanism to bear on struggles for justice, democracy, and self-determination across a range of global sites. He is the co-founder of a series of militant research collectives, including Detroit Resists, the Settler Colonial City Project, and the We the People of Detroit Community Research Collective. He is the author of several books, most recently Under the Campus, the Land: Anishinaabe Futuring, Colonial Non-Memory, and the Origin of the University of Michigan, which is forthcoming in 2025. He works at the University of Michigan.

Sonali Dhanpal is a historian of modern architecture and urbanism who specializes in histories of colonialism, capitalism, and inequality. Her projects on South Asia and Britain focus on the relationship between architecture and the social reproduction of race, caste, and class-based unfreedom. She received her PhD in Architectural History and Theory in the UK in 2023. She arrived in the United States as a post-doctoral fellow a few months before campus protests for divestment began. Her research examines how histories of land, property, and housing are fundamentally connected to contemporary struggles for space under racial capitalism. She is a fellow at the Buell Center and the Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities at Columbia University.