“The past, or more accurately, pastness, is a position”

— Michel-Rolph Trouillot (from Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes)1

“Writing through or about grief is a confrontation with containment, both in the self and on the page. It sanctions an inclination to digress, not only because revisiting is an organic and necessary part of the experience, but because it is an unstable state and subject, prone to a volatility that resists attempts to find forward motion or shape.”

— Raven Leilani, “Death of the Party”2

In the fall of 1972, protests erupted in Cambridge, MA, in the days following the murder of seventeen-year-old Larry Largey by police officers Peter DeLuca and Rudolph Carbone near Roosevelt Towers in East Cambridge. Police had arrested Largey on the night of October 21 on the grounds of allegedly breaking a storefront window at 950 Cambridge Street.3 According to an official report, the police were not present at the incident, but they eventually followed Largey down Windsor Street. When Largey resisted arrest, stating he wanted to go home and offering to pay for the window, a fight ensued: Largey’s three friends, including nineteen-year-old Thomas Doyle, ran over to the scene to forestall the arrest. The police called for backup; officers drew their nightsticks and forced Largey and Doyle into the police paddy wagon. Eyewitnesses reported hearing a loud commotion from within, the paddy wagon rocking back and forth, and screams from outside.4 Largey—having been beaten so badly—was discovered unmoving in his cell at 3 a.m. and was pronounced dead at the hospital soon thereafter.

Less than a day after the death of their classmate and neighbor, protests erupted in East Cambridge. As the community continuously demanded answers, a month after Largey’s brutal killing and weeks of demonstrations, the City of Cambridge published the 100-page “Larry Largey Report.” Written by city-appointed Boston University Law Professor Paul J. Liacos (later a Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court), the “Investigation Relating to Alleged Police Misconduct” details the step-by-step interactions between Largey, Doyle, the police, and eyewitnesses on the night of October 21, which culminate in his death. In reading the authoritative document, we learn that, as outlined above, when the boys acted in self-defense, they were met with more police force. We also learn that when police first brought the boys into the precinct for their arrest, officers failed to enter Largey’s name into the desk journal. Largey’s custody was entirely omitted from any accounting that night: the October 21, 1972, records for Cell No. 9—where Largey was held—in the journal are blank. While Doyle’s name was recorded by DeLuca in an entry marked “11:40 pm,” there was no record of Largey’s arrest in the book. Only Doyle has a 5x8 “file card” for his arrest. This blatant and purposeful gap in the archive animates a long history of ghosting, erasure, and silencing through which state entities wield their power. If not for Largey’s tragic death, his treatment by officers at his arrest would have gone unrecorded. The beating, a result of literal “broken windows” policing, would have been kept out of the official record, severely compromising the possibility of recourse.5 The bureaucratic records of the Largey Report thus reveal the limitations of the act of witnessing, if left to the state’s narratives, as official wrongdoings are left illegible, unrecorded, or allowed to metaphorically or literally decay.

To enter the story of Larry Largey’s last night through the bureaucratic state’s archive marks an urgent need to learn about the story from community perspectives. The report lists the specific uses of violence on that night. It leaves out the vastness of the many everyday violences surrounding the incident—of the daily specter of policing, of one’s environment wrought by neglectful public housing policies, of the lack of accountability and justice by the city—nor can its sheen of “objectivity” communicate the emotional fallout of Largey’s death. To experience this report is to encounter other gaps in the archives: an absence of the voices of those affected by state violence, an alienation of their resistance and their everyday lives outside it. I endeavor here to offer a more robust archive through both informal and formal methods: interweaving a history of housing and policing, supported by primary documents, through oral histories and interviews conducted with Cambridge residents active in the Largey protests, and through the immersive and informal photographs of Olive Pierce. These photographs, highly attuned to the spectrum of everyday life in Cambridge, compel further inquiry into overlooked histories of movements toward freedom in the city alongside gentrification, dereliction, and displacement.

Two Weeks of Unrest in Roosevelt Towers

“The next day, a group of us saw the ignition of a car in flames turn on, with nobody inside. We said, that’s Largey’s ghost in the car!”

— David Owens, interview6

The riots that broke out in the days following Larry Largey’s death took place in Roosevelt Towers, the only public housing project in the Wellington-Harrington neighborhood of East Cambridge. The neighborhood, where Larry lived with his Irish immigrant family, had a diverse working-class population—majority Irish-immigrant, Latin American immigrant, and Black families. David Owens, a former resident of Roosevelt Towers and a friend of Largey’s, shared with me: “That night [that] Larry was beaten to death—they said it was an overdose, but it wasn’t. The police said they didn’t know him, but they did. Largey had gotten his first paycheck from his first job,” he said.7 “He was trying to do the right thing.” Owen’s uttering of “the right thing” lays bare the harrowing yet all-too-familiar nature of the arrest. The paradox of a young boy’s celebration of a milestone leading to his very demise reveals the unspoken design of policing that is the protection of a very specific kind of property, that which is meant to protect entrenched power.8 Stopped by the police for, as stated, a literal broken window, Larry was subject to policing of the subjective actions of loitering, vagrancy, and simply walking down the street at night.

It was the killing of a seventeen-year-old boy by police officers that overflowed an already-bitter cup. “The next morning, someone came by the house and woke us up,” Owens told me. “I had eight siblings; we all knew Largey. He was like a big brother to me.” In the days that followed Largey’s death, Roosevelt Towers became a hub of community resistance wherein young people convened and vented their frustrations about policing. “We were furious that the city didn’t do enough to investigate his death. We knew that cops would stop young people as an excuse to beat us up. It wasn’t new. Mothers were just worried about which one of us would be next.”9 Cambridge youth took to the streets to burn cars, paper vehicles with anti-policing pamphlets, loot businesses on the busiest street in the city,10 and stop traffic. Many young people were injured by confrontations with the police. Many of them also showed up to city hall in the days following the news, hoping to see the police officers charged for Largey’s death. No one was charged, and the riots continued for two more weeks. At the height of the unrest, federal military officers held ground in a nearby field; patrol cops threw tear gas canisters at the rioters, who threw the canisters back.11

The aftermath of Largey’s murder speaks to the tragedy of the ongoing police violence that took place in Cambridge at the time, and the indifference of the local government to the city’s working-class community. Many accounts of the riots referenced the Largey report and its detailed recommendations for leadership to take action against the police officers—recommendations that were never acted upon.12 For the working-class community and the trajectory of the city’s politics, the uprisings were part of negotiating everyday policing.13 “I was probably in the single digits when I first was aware of being policed,” David Owens shared. “In the projects, I hung out with my older brothers and their friends. We spent time in the parking lots or in each other’s apartments. We knew the police were thugs back then—they couldn’t be trusted. I’d never been in a criminal justice case where cops had to testify.”14 Largey’s death was not the first incident of police brutality, state violence, and neglect in Cambridge, and it wouldn’t be the last. Less than two years later, in 1974, not far from where Largey was killed, the police beat Clarence Anderson, who lived the rest of his life blind in his right eye from where an officer kicked him while Anderson was on the ground.15 In 2023, about fifty years later, twenty-year-old Arif Sayed Faisal was killed by the Cambridge police, a case that the family and the community are still processing. It took almost a year for the city to release the name of the officer involved.16 Although Largey was white, of Irish descent, his death at the hands of the police, and the lack of accountability for this violence, can be situated in a broader pattern of neglect and marginalization of poor communities and communities of color at the time. Residents who were organizing against this brutality made the clear connection between poverty, racism, and policing: Largey’s death—and the protests that followed—were only part of the numerous, intersecting, and ongoing challenges that the public housing community faced. These challenges were encoded into legislation (or its absence) and enforced by police.17

At the same time, the space of public housing itself encouraged the formation of early political enclaves among youth and enabled neighborhood residents to carve out social belonging against the police in Cambridge. “People would crowd into our apartment,” David Owens said. “They knew our door was always open. Doors were kept open for people to come inside each other’s apartments—if cops caught you out of your home after dark, you were in trouble. Cops came from every part of the city. National guards were even stationed behind Donnelly Field.”18 Owens’s account of the close-knit residential life challenges entrenched public depictions of residents in public housing: one 1973 Crimson article, for example, describes the Roosevelt Towers as “the worst public housing unit,” claiming that “Roosevelt Towers has been plagued by violence. Three times in the past three weeks, over 100 youths have battled with pipes, bottles and bricks on the development’s grounds,” adding also, “Mailboxes have been ripped from the wall, probably by thieves looking for checks.”19 The article ignores the context of these riots in favor of assumptions of moral corruption. On the contrary, Owens’s description challenges the entrenched narrative, revealing how community members in Roosevelt Towers connected around the events that unfolded through mutual support and shared experiences. Owens’s narrative of the residents convening in domestic spaces and discussing encounters with police illustrates the powerful forms of knowledge and solidarity produced here.

Looking at and listening to the reality of the riots also sheds light on expanded histories of residents working fiercely to resist the violence of policing in public housing at the time. Saundra Graham, for instance, a Black city councilwoman elected in 1971, drew from her local organizing experience with residents in Riverside to address police brutality and unresolved social discrimination and seek justice for the Black community. Graham responded to the killing of Largey by pushing for—and successfully securing—increased representation of Black officers on the Cambridge police force. While the limits of such reforms must be acknowledged, particularly that the inclusion of Black police officers does not fundamentally address the police as an agent of white supremacy, where Black officers are often deployed to police their own communities of color, Graham’s work became a benchmark in Cambridge community politics: residents saw her as one of the few people in the city brave enough to stand up for the Black community on the issue of police violence.20 Graham’s organizing went beyond tackling policing, addressing the concerns of working-class people in Cambridge. To honor her recent passing in 2023, the city nodded to her integral role in instilling democratic ideals as a community organizer:

Because of her action, Harvard finally acknowledged publicly its covert role in what was actual displacement of long-time residents from their homes. Harvard responded by constructing an elderly housing complex and ten years later, a family housing complex. Later, she played a key role in obtaining federal housing dollars for Cambridge. Roosevelt Towers, Jefferson Park and Washington Elms public housing complexes received comprehensive rehabilitation and modernization funds through her efforts.21

Graham’s legacy of organizing is not only one of making visible the often-overlooked working-class community in Cambridge but one of asserting that the city’s democratic ideals hinged on their very political movements and voices.

The fires that started in response to Largey’s death were similar to the fires that Cambridge activists set during their protests in demand for rent control at that time. In 1969, just three years before the killing of Largey, city council refused to pass rent-control laws—essentially arguing that “it didn’t work in New York, so it won’t work in Cambridge.”22 Despite this dismissiveness from city government, residents made their voices heard: before she was elected to the city council, Graham led a group of neighborhood residents in disrupting a Harvard University commencement, demanding recognition of its continued real estate expansion as a form of displacement. It was, for many, a matter of life and death, and marked a need to push back against routine state negligence. Janet Rose, a resident activist in the seventies, told me in an interview at her kitchen table: “When we were fighting for rent control, we weren’t quiet or shy. We had nothing to lose. Attending a critical hearing… in the 1980s, when the city threatened to end rent control, we put trash barrels in front of City Hall, blocking traffic. We lit them on fire. That got the media to show up... We knew that this was a turning point for Cambridge. If we didn’t win, Cambridge would become a very different city.”23 Rose, a mother of five, became involved in the housing movement when the door to her home wouldn’t close. In the winter, snow would come into the hallway. “I lived in Newtowne Court. I’d call to get my door fixed over and over. No one ever came. For many women like me, this movement was about survival.”24 Following the story of policing alongside these histories marks a hopeful yet necessary refusal by residents to be flattened into the very subjects that the police and other dominant forces intended to make them.

Revisiting the Archive Through Pierce

When I first encountered the 100-page Largey Report, I hesitated to open the black-and-white authoritative pages of the document.25 I wondered about what it meant to encounter the life of a boy, and his friendships, through the entry point of the report—one intended to provide answers for residents from an objective perspective, wherein the language, tone, and form take on the logic of governance. At times acknowledging the confusing and contradictory web of testimonies between police officers, witnesses, and Thomas Doyle, the report details a choreography of violence in a step-by-step, monochromatic tone. There is repeated mention of police weapons—a nightstick, a billy club. There is repetition of events—who went into the paddy wagon, when they entered, with what weapons, when the door of the paddy wagon was closed—told from different perspectives to promise a full spectrum of possibilities of the events. What are the perils of reading about Largey’s death through the state archive, which prioritizes chronological order and legibility? How might the very project of creating evidence through legibility impede a slowed-down experience of taking in the events of Largey’s death—one that allows for mourning the gravity of it?

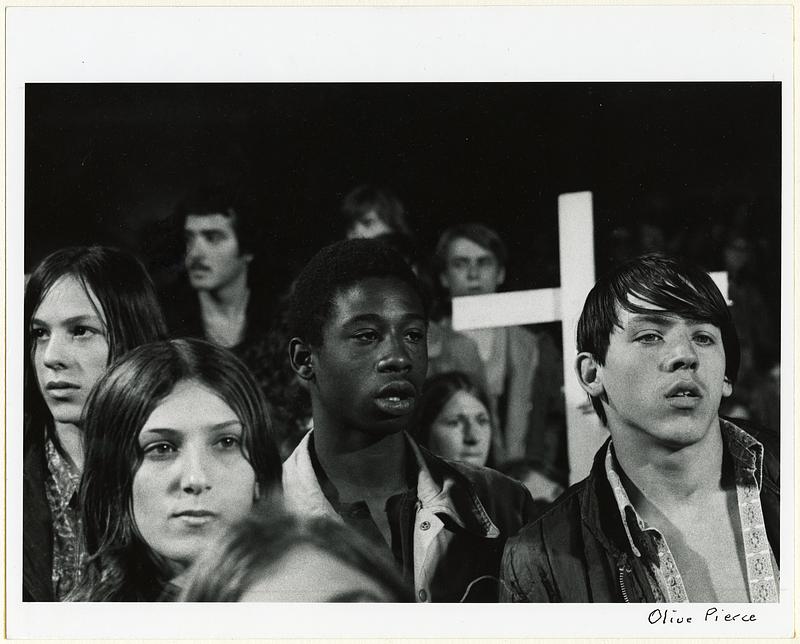

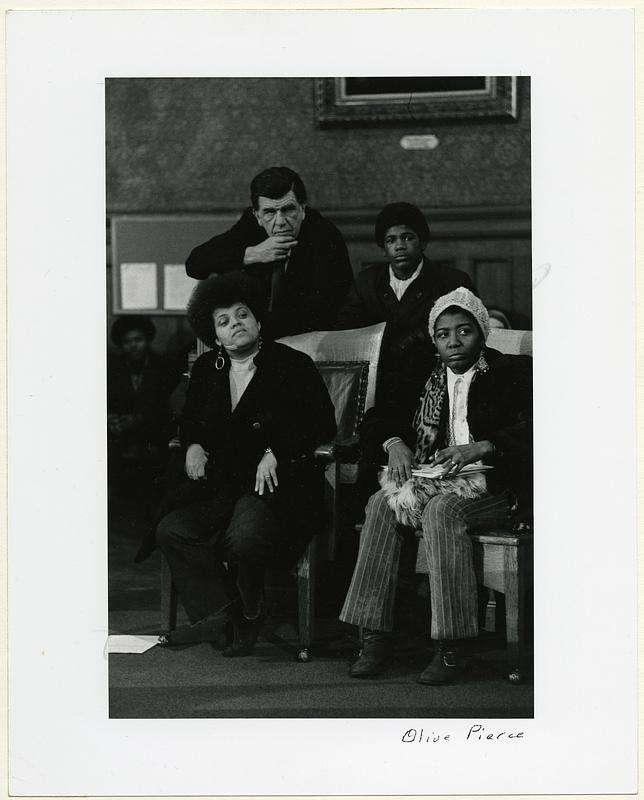

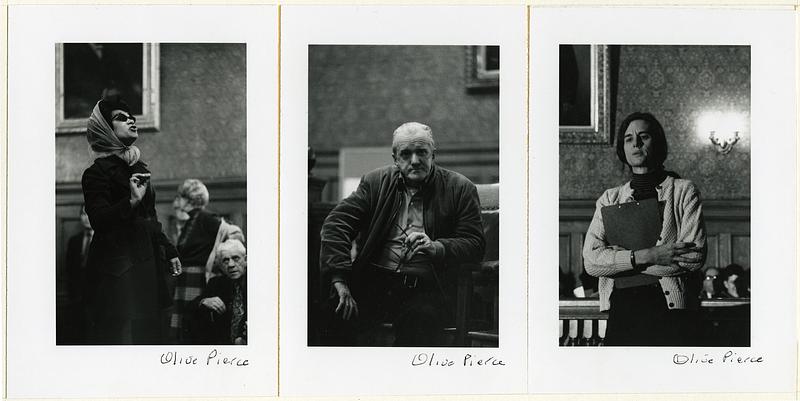

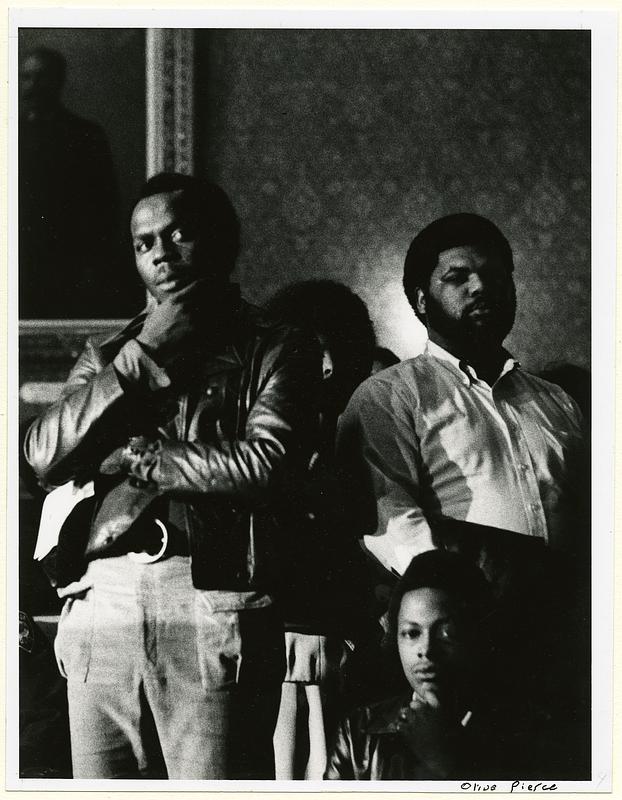

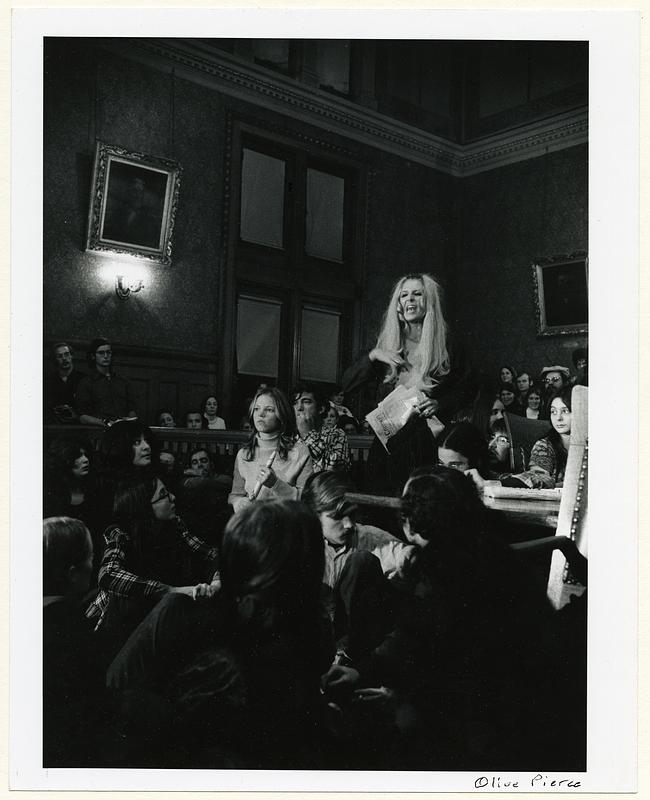

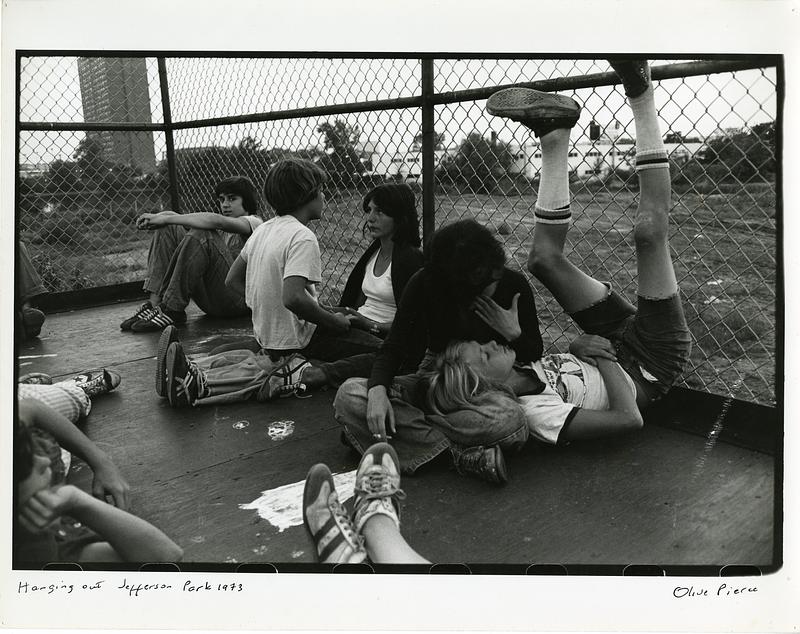

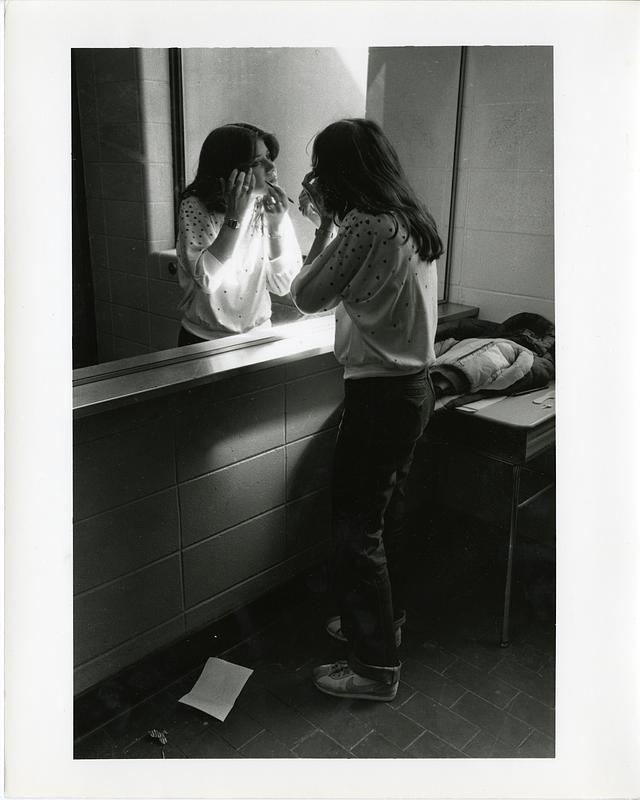

It wasn’t until Cambridge Public Library archivist Alyssa Pacy, who first showed me the Largey Report, also pointed me to the archive of documentary photographer Olive Pierce that the opportunity for a renewed encounter with the text emerged. Pierce’s images of life in Cambridge—“No Easy Roses” (1982–1985), documenting youth culture in the public high school, Cambridge Rindge and Latin; “City Hall Hearings” and “Police Brutality Hearings” (both 1970–1972), recording on-site rent-control hearings, municipal icons, and political transitions; “Jefferson Park Series” (1973–1975), depicting ordinary residential life in public housing in North Cambridge—exemplify the paradoxical images of this particular moment that defined Cambridge’s history. With two images of those who testified and listened to the police brutality hearings following Largey’s death, her photographs offer an alternative entry point into the event. The images are buoyant with life. These, when considered within the spectrum of Pierce’s body of photographs of Cambridge, offer a blueprint for sensing, imagining, and interacting with the intimacy of fighting for justice for Larry Largey and for the safety of the community experiencing the specter of policing in their neighborhoods. The images deliver everyday moments that rupture the official archive’s own sterile telling of state violence; they capture residents in the streets, of families going about their daily lives. The images give locomotion, narrative, to the personal and political archive of a city grappling with loss, allowing viewers to move away from the official documents as sole sources of understanding the events and their implications.

With a photography career that spanned forty years, Olive Pierce’s practice mixes kinetic street photography, introspective portraiture, and on-location documentation of major political municipal hearings. Pierce’s camera seems to have been a steadfast companion in her immersion in Cambridge, where she taught photography. In her expansive body of work, the texture of life and the embodiment she captures—attuned to her subjects’ environment, families, peers—adds visual testimony to this moment in Cambridge’s ongoing political and cultural history of unrest and social change. The images show the sheer numbers of the many people, including young people, who showed up to rent-control and police brutality hearings. While her practice documents events that took place in the spaces of “formal” politics, she just as much redirects viewers’ focus toward the lives on the streets and in public housing communities.

Pierce’s “Police Brutality Hearing” photographs make plain the convergence of terror, disbelief, and the continuous resistance in the space of communities who lost their neighbor, and the mothers worried for their children’s safety from violence at the hands of the police. Pierce’s work reflects the heavy response of Cambridge residents at the time: students peeking over the City Hall Chamber booths; Janet Rose delivering her testimony during rent-control hearings; Saundra Graham sitting with her collaborator Joanne Pelham, gazing beyond the camera; George Greenridge’s soft-gazed presence during testimony at the police brutality hearings in January 1971, which preceded Largey’s death26; Wellington Court resident Michael Provencher testifying about his own police beating in 1971, a bandage covering the right side of his forehead; Roosevelt Towers resident “Mrs. McCartney” rising above her peers to give comment during Larry’s hearing; students from Roosevelt Towers in the high school auditorium holding vigil, their eyes gleaming. The courthouse portraits are taken at eye level; the subjects are centered. From my vantage, their expressions appear to communicate weighted joy, anticipation, need, exhaustion.

Significantly, Pierce’s archive contains only one image of the actual rioting following Larry Largey’s death, and only three images of the 1972 hearings. What it offers in abundance are glimpses of how youth grew up in Cambridge, how Larry might have lived: her portraits capture students in bomber jackets building a weight-lifting gym; girls doing makeup in the school bathroom; kids and families loaded up in open-windowed cars in the parking lots of Jefferson Park; youth playing with old tire wheels outside strip malls; dozens of laced-up middle schoolers squeezed together against a fence, lounging on each other’s laps; students attending an unnamed classmate’s funeral, adorned in flowers. Depicting subjects fully in their social contexts and often in conversation with one another, the images afford the viewer a certain intimacy with them and make visible what community life and spaces residents fought to secure and maintain. How might Pierce’s work help us imagine the full arc of the lives of those she chose to photograph?

In her photographs, Pierce does more than recount the violence that deposited these traces in the archive, or the violences that made a boy into an account book, a 5x8 index card with missing information, the banal chronicles that stripped him of life. Here, there is a story of what could have been—and what was: a whole community speaking with their own voices to retrieve the life of their classmate against the routines of forgetting.

Lessons from the Roosevelt Towers Riots and Community Art Center Films

What dual legacies might the Roosevelt Towers uprisings and the continued struggles against policing leave us with in terms of possible futures for Cambridge? In the span of the last fifty years since Larry was murdered by police, community members and public housing residents in Cambridge have continued to negotiate policing and gentrification. Pierce’s images, and the oral histories of those who remember Cambridge so vividly, collapse ongoing histories of everyday refusal in the interest of recentering them. More than that, a mixed-method reading of this period complicates trite representations of police violence and urban practices of place-making as a space that is politically unconscious and reminds us of the overlooked history of the multitudes of residents at work toward practices of freedom. Reading images and making sense of oral histories presses us to face what the scholar Dixa Ramírez calls “ghosted” realities that these materials gesture at, probing and inviting further questioning into the ways our engagement with materials may silence those practices of freedom.27

Nearly twenty years after Pierce photographed the police brutality hearings, young people living in public housing, specifically Newtowne Court in the Port, documented their own stories of policing and resistance. In early 1990, through the Community Art Center, they made films that documented student organizing in Cambridge and Roxbury against violence, where students demanded visibility in the aftermath of deaths of young people, otherwise routinely swept under the rug or seen as normalized.28 For the Black and Brown communities in the Greater Boston area, especially after Charles Stuart murdered his wife in 1989 and tried to blame a Black man—police violence often involved intimidation and personal invasion practices like frisking.29 “In the late 80s and early 90s, Police would terrorize the Cambridge Black community, like they had permission to do whatever they wanted without repercussion.”30 Susan Richards, a community organizer from Cambridge who worked with young people during this period at the Community Art Center, helps complete the picture between Pierce’s documentation practices and Owens’s interview, filling in further what is missing from the official record:

The young people in the program grew up in a neighborhood that was heavily policed. Families were not protected or listened to. Too many community members have died of violence, overdose, and the impacts of economic struggle, racism and health disparities. This is the forgotten Cambridge. The young people in the program questioned, advocated and told their stories through their photography and documentary films airing on public access television. The archives reflect the resistance and beauty of our youth and their community. The Community Art Center youth took it a step further in 1996 when they founded the first national youth film festival showcasing the films of youth from low income and Black and Brown communities across the country, most often marginalized.31

For teenagers living in public housing projects, Newtowne Court and Washington Elms, documenting their own political questions and daily lives demonstrates how young people used cinema to hold the possibility of counternarratives, and to steal away from the official records to show what they hid or were never able to hold at all. Through films like Civil Rights: How Far Have We Come?, Black Is Beautiful, and Teen Parenting, as well as the film Organizing and Coming Together, students portrayed creative Black visual practices of disobedience. Each of their works beautifully uses collective art-making practices as invitations to reconsider what seems obvious. In Organizing and Coming Together (1990), filmmakers capture the community who showed up to mourn the losses of their neighbors Rigoberto Carrion and Jessie McKie, residents of Cambridge’s Area Four.32 While this film wasn’t specifically about police violence, students still intervened in a world they are working against, flipping the script to make evident a community that showed up and refused to normalize violent death. Here, students demand the building of local political apparatuses to address ongoing grief and state negligence. In making the film, youth who lived in public housing created their own space for their community to mourn, organize, to witness each other in loss, take up space, and tinker with the material of documentation for their own (mis)use.

That youth growing up in public housing preserved their collective mourning and organizing practices through film not only means we can now sit with a map of their experimentation, creation, and revisions of the racially codified narratives about violent death. It also tells us that residents were careful and intentional in the curation of their own stories, as if anticipating curious researchers and community members to go looking for more answers. These materials—housed at the Cambridge Public Library—serve as a bridge, giving insight to how residents continue to make connections between their own autonomy and state power. In the aftermath of ongoing routine policing in low-income neighborhoods, as Richards points out, the continued demands for justice demonstrate how thoroughly the state sanctioned practices of violence, even as they are challenged through the brilliant work of organizers like Janet Rose and Saundra Graham, remain intact.

These practices—of both violence and resistance—are still ongoing. Sayed Arif Faisal, who lived in affordable housing in Cambridgeport, was killed at the hands of the Cambridge police in 2023 at twenty years old. Local communities demanded the names of the perpetrators and sought justice, but ultimately the police officer responsible for Faisal’s murder was not prosecuted.33 In 2021–2022, Black students created “Community For Us By Us” (FUBU) and organized with the Black Student Union at Cambridge Rindge and Latin, attempting to establish abolitionist policing alternatives, specifically at Rindge. Despite these efforts, as one student shared with me, when the group expressed their experiences around policing at school committee hearings, the mayor quickly shut them down. “She accused students of faking their encounters and interactions they shared with the police to be able to get out of doing schoolwork.”34 In the face of such continued erasure, it is critical to return to the voices of those who continue to speak and organize against the larger structural effects of policing that leave marginalized residents further alienated and estranged from their own cities.

In unearthing and performing an expanded reading of the visual archive and oral histories surrounding police brutality in Cambridge throughout the 1970s, and into the 1990s and 2000s, I hope readers find renewed curiosity toward a deeper witnessing. In taking Pierce’s images seriously, the future and history that collapse around her work become available to us through secrecy, ambiguity, and the unruly. Inviting a slowed-down encounter with representations of our local histories also invites multiple ways of refusing the ugly totalities of unfreedom: how many people showed up to testify against state violence; what questions and political desires remain; for the students and residents from this time, what has changed in fifty years since this marker, and what are they still dreaming of? In a time of such heightened witnessing of genocides and battles for justice and redress, there is a persistent question of how we generate knowledge of state-sanctioned violence while refusing to flatten its victims’ deaths into data, numbers, tropes, corpses, where the study of violence threatens to replicate the death work of the state’s register. How do we insist on representing their full lives, their modes of self-determination toward freedom? When and how do we reveal what we have witnessed and what we know? Together, the deepened reading reconfigures how we understand, employ, and carry forward these everyday residents’ sociopolitical, cross-cultural calls for justice and power as an everyday praxis in the built environment and beyond.35

-

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995), 15, quoted in Christina Sharpe, “Note 3,” in Ordinary Notes (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023). ↩

-

Raven Leilani, “Death of the Party,” n+1 48 (Fall 2024), link. ↩

-

Cambridge, MA, Police Department, “Larry Largey Report: A Report to the City Manager Submitted by Paul J. Liacos, Investigation Relating to Allegations of Police Misconduct on Oct. 21–22, 1972” (November 22, 1972), 19. ↩

-

Eyewitness accounts from pages 28–29 of the Largey Report; Mrs. Elizabeth O’Brien’s account is on page 32. ↩

-

“As is taught in Broken Windows 101: disrespect for authority and non-compliance by the criminal element can lead to the breakdown of civilization.” Jordan T. Campt and Christina Heatherton, “Introduction: Policing the Planet,” in Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter, ed. Jordan T. Campt and Christina Heatherton (Verso, 2016), 19. ↩

-

David Owens, former Roosevelt Towers resident, phone discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

David Owens, in discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

Footnote for Orlando Patterson’s definition of social death and sources on PIC and social death ↩

-

David Owens, in discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

Rioting and looting are often vilified, even by progressives and activists, for their violence against property. In her book In Defense of Looting, Vicky Osterweil reframes these actions as important tactics in the struggle for liberation and against injustice. See Vicky Osterweil, In Defense of Looting: A Riotous History of Uncivil Action (Bold Type Books, 2020). Publishing an article first in the aftermath of the Ferguson protests in 2014, Osterweil responds to the well-meaning defenders of nonviolence, critiquing: “If protesters hadn’t looted and burnt down that QuikTrip on the second day of protests, would Ferguson be a point of worldwide attention? It’s impossible to know, but all the non-violent protests against police killings across the country that go unreported seem to indicate the answer is no.” ↩

-

David Owens, in discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

These were: 1) That the City Manager initiate, either himself or through any proper municipal officer or agency, the appropriate disciplinary proceedings against Officer Peter E. DeLuca; 2) That the City Manager or the Chief of Police take such disciplinary action against Officer Rudolph V. Carbone as may be deemed appropriate in light of these findings; 3) That the City Manager or the Chief of Police take such disciplinary action against Lieutenant Anthony J. Temmalb as may be deemed appropriate in light of these findings; 4) The City Manager or Chief of Police take disciplinary action against Lt. Anthony Temallo as may be deemed appropriate in light of these findings; 5) That the City Manager and the Chief of Police take such other action in regard to findings herein made as they may deem appropriate in the circumstances, including but not limited to, disciplinary proceedings, reprimands or censures of other officers herein named in regard to their failure to effectively discharge their assigned responsibilities. From page 77 of the Largey Report. ↩

-

This is outlined in the statement by the Coalition to Combat Racism; their demands were listed by guest writer Calvin Hicks in the *Harvard Crimson in 1974. See Calvin Hicks, “Racism and the Police,” Harvard Crimson, October 1, 1974, link. This “everyday policing” may be further elucidated with Dilara Yarbrough’s definition of “carceral”: “ I use the term ‘carceral’ to refer not only to jails and prisons, but rather to a broader ‘carceral system,’ encompassing laws and their enforcement through policing, and ‘carceral state’ that uses punishment to govern in the service of capital. These analyses build on Foucault’s (1977) conceptualization of a ‘carceral archipelago’ that includes technologies of surveillance and social control related to, but extending beyond, jails and prisons.” See Yarbrough, “The Carceral Production of Transgender Poverty: How Racialized Gender Policing Deprives Transgender Women of Housing and Safety,” Punishment & Society* 25, no. 1 (2021): 141–161. ↩

-

David Owens, in discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

“Unreleased Report Calls Cambridge Arrest Brutal,” Harvard Crimson, October 12, 1974, link. ↩

-

Ryan H. Doan-Nguyen and Yusuf S. Mian, “Cambridge Police Officer Who Fatally Shot Sayed Faisal Will Not Be Prosecuted Following Inquest,” Harvard Crimson, October 11, 2023, link. ↩

-

Most notably with Cambridge’s urban renewal program in mid-century, which was essentially a slum clearance campaign: “In an attempt to counteract Cambridge’s deterioration, the city administration created the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority in the early 60s, marking the beginning of urban renewal in Cambridge.” Rediet T. Abebe, “City Sees Urban Renewal,” Harvard Crimson, May 23, 2011, link. The “Mapping Project” outlines how the city and its major universities used urban planning to displace existing Black and Brown communities: “At the end of WWII, Cambridge was a working-class, immigrant city: it was still home to factories, organized labor, and racially integrated neighborhoods, despite the redlining of its historically Black neighborhoods. As the war ended, however, universities seized the opportunity to turn what they saw as ‘slums’ into research and development centers for the reconfigured war industry. Harvard’s push for urban removal (‘urban renewal’) was also motivated by a nakedly racist white fear of the surrounding communities, with one Harvard student claiming the university was ‘in the position of a man about to be eaten by cannibals.’ In 1956, Cambridge’s unelected city manager (empowered under Plan E) appointed José Luis Sert, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), as chair of its planning board to steer urban renewal in the city. Collaborating with municipal offices filled with their alumni, MIT and Harvard’s urban planning departments advocated bulldozing entire neighborhoods, especially majority Black and Brown neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were replaced by developments like Kendall Square that house the companies and academics working for the US war machine, with Pentagon sponsorship.” See “Boston’s Colonial Universities Grab Land for Profit, War, and Medical Apartheid,” Mapping Project, June 3, 2022, link. ↩

-

David Owens, in discussion with the author, March 2024. ↩

-

Lewis Clayton, “Roosevelt Towers Burns While Bureaucrats Fiddle,” Harvard Crimson, September 17, 1973, link. ↩

-

In Dylan Rodríguez’s analysis of the “Join the LAPD” campaign, he makes clear that representational initiatives function to incorporate minoritized differences while simultaneously naturalizing state violence against members of the same racialized groups who join the ranks. How might the inclusion of more Black and Brown cops come at the expense of marginalized people? See Dylan Rodríguez, Kim Wilson, and Brian Sonenstein, hosts, with Dylan Rodríguez, Beyond Prisons, podcast, “Dylan Rodríguez, Part I: Abolition Is Our Obligation,” Beyond Prisons (podcast), July 30, 2020, link. ↩

-

Bob Gustafson, “Cambridge Rent Control Defeated Again,” Bay State Banner 5, no. 47 (July 31, 1969): 1, link. ↩

-

Janet Rose, in discussion with the author in person, February 2023. ↩

-

Janet Rose, in discussion with the author, February 2023. ↩

-

At first glance, I think of artist Sadie Barnette’s FBI Project (2016–ongoing), where Barnette takes up her father Rodney Barnette’s FBI files—inserting herself into the retelling of her familial history. Barnette adds pink annotations and bold glitter to the state-produced documents that were used to track her father’s participation in the Black Panther Party: “I wanted to reclaim them and make them live in my world.” See link. ↩

-

George Greenridge is a longtime Port resident who grew up going to the Margaret Fuller House, a local hub for community service and neighborhood engagement,was a physical education teacher at Cambridge Rindge and Latin and a football coach at the high school. ↩

-

Dixa Ramírez, Colonial Phantoms: Belonging and Refusal in the Dominican Americas, from the 19th Century to the Present (New York University Press, 2019). ↩

-

“There had been no Black assailant. Stuart had killed his own wife and child and spun a fantasy that led police to terrorize the Black community and arrest innocent men… Some officials began calling for the return of the death penalty in Massachusetts. Boston’s mayor, Raymond Flynn, declared a citywide manhunt for the killer. The police took Stuart’s word in what now looks like a textbook case of systemic racism.” See David Smith, “‘We failed the city of Boston’: How a Racist Manhunt Led to Chaos in 1989,” Guardian, December 7, 2023, link. See also the HBO series Murder in Boston: Roots, Rampage & Reckoning, dir. Jason Hehir, 2023. ↩

-

Charles Stuart murdered his wife, but attempted to blame a Black man who hijacked his car, triggering a manhunt to find the suspect. The state ascribed collective guilt to the Black community in Boston, offering the state a patina of “legitimacy” in their punishment. See Jack Hamilton, “Murder in Boston Delivers a Long-Overdue Reckoning,” Slate, December 4, 2023, link These videos were made right after the Charles Stuart murder case, after which the police accused Black people of the murder at random and stormed their homes without warning. ↩

-

Susan Richards, in email to the author, November 2024. ↩

-

Michael K. May, “Two Men Get Life in Prison,” Harvard Crimson, February 14, 1992, link. ↩

-

Deborah Becker, “Inquest Clears Cambridge Police in Fatal Shooting,” WBUR, October 6, 2023, link. ↩

-

From an interview conducted with a founding member of FUBU, in discussion with the author, March 2023 and October 2024. ↩

-

The Palestinian poet Hala Alyan calls forth a witnessing beyond the courthouse, the libraries and the archives, the university. “In the face of incomprehensible destruction, what does the diasporic witness have to offer?” Alyan asks. “What do we build in a rift the size of countries? Our poetry? Our hoarse voices at a protest, seared by what we’ve been spared? A last name pronounced in two languages. The promise of a long, unruly memory.” A capacious reading of the archive thus acts as an invitation to speculate on the many modes of existence that live through the hold that carcerality has on contemporary daily life, desire, and imaginations of freedom. See Hala Alyan, “‘I Am Not There and I Am Not Here’: A Palestinian American Poet on Bearing Witness to Atrocity,” Guardian, January 28, 2024, link. ↩

Lucy Sternbach grew up in Cambridge, MA. She’s written for Brooklyn Rail, Film Comment Magazine, Screen Slate, and for Roxane Gay’s Emerging Writers Series.