“We are eating patience with its thorns,” says a man in the northern Gaza Strip, as he cuts into a pad of sabr صبر—the Arabic name for the prickly pear cactus, which also translates to “patience.” This moment, recorded by the photojournalist Mahmoud Awadia and uploaded to social media in February 2024, captures the cruel realities faced by thousands of Palestinians who have refused to leave their homes despite the forced removal and displacement; the deliberate starvation and imposed famine; and the continued aerial bombardment of residential buildings, schools, hospitals, and farmlands since the Israeli Zionist military invasion of Gaza in October 2023.1 Over a year into this ongoing genocide, domicide, and ecocide, what little remains of previously thriving cactus populations—alongside other local herbs and weeds—has now become a critical source of nutrients.

It is not a coincidence that these prickly pear cacti grow throughout Palestine. For centuries, Opuntia ficus-indica, the most common prickly pear cactus species in the Mediterranean, was planted by Palestinians as hedges to demarcate village boundaries and agricultural fields. With its high tolerance to drought and extreme heat, these fruit-bearing plants can grow and regrow in the most challenging of environments. This is due in large part to a photosynthetic adaptation found in only 6 percent of the world’s vascular plant species, evolved to survive in arid conditions. While most plants draw in carbon during the day, these plants, in order to conserve water, draw in carbon at night, when temperatures are cooler.2 At its most biological level, the cactus employs a form of patience as a means of survival.

It is no wonder, then, that the prickly pear cactus has become a deeply resonant cultural and political symbol for Palestinians. It is this very patience and resiliency with which Palestinians have long identified in the various stages of their resistance against the Zionist settler colonial invasion. The Palestinian historian Shukri Arraf documented a few of these earlier instances in his book Land, Human and Labor:

Sabr is useful for fencing vineyards and orchards, and it is cheaper than barbed wire. In the plains, it is easier to use when constructing fences due to the absence of stones. This is most clearly seen in Gaza. Its fruit is desirable, and some people prefer it over figs. The locals made molasses from it during the war... One of the rare events that happened after the 1948 war between Israel and the West Bank was that the residents of Faqou’a planted prickly pear pads to the north and east of their village to form a barrier between them and Israel. Over time, the residents began to collect its fruit and market it, even in the Gulf countries.3

After the 1948 Nakba—the catastrophic ethnic cleansing of Palestinians at the hands of Zionist militias, through massacres, the forced displacement of survivors from more than 500 villages and towns, the massive destruction of their properties, and the bulldozing of their agricultural lands—the newly established Israeli state undertook extensive terraforming campaigns. In a deliberate act of erasure, pine forests were planted across historic Palestine, replacing vernacular vegetation and concealing the ruins of destroyed villages. This effort, led by the Jewish National Fund (JNF),4 aligned with the century-long project to reimagine the land in Western ideals, reinforcing colonial narratives of the “Holy Land” while obscuring Palestinian histories. And yet, today, cactus hedges are reemerging among the introduced pines across multiple sites in historic Palestine. They retrace the once-erased boundaries of these villages destroyed in 1948. This deeply rooted cactus, which can grow numerous pads a year and reach several meters in height, bears witness5 to the violence of dispossession: it is a living testimony to the histories of Palestinians.6

This species has entered the “wild” and broken free from its once-tended boundaries, forming entanglements and relations with other plant species.7 However, botanically speaking, Opuntia ficus-indica cannot exist in the wild. Long before growing in Palestine, it was bred over thousands of years by communities in Mexico to have thick spineless pads, both for food and for hosting domesticated cochineal (an insect known in Spanish as grana cochinilla fina, or grana fina), used in dyeing.8 These uses, which have shaped both species as we know them today, have not been commonly practiced in Palestine.9 If anything, the recent spread of cochineal in the Mediterranean region over the past ten or fifteen years10—which is now decimating local cactus populations—is viewed as a plague by farmers, and eating the pads is seen as either exotic or, as the man in Gaza put it, as an act of “eating patience with its thorns”—a last resort amid forced starvation.

As the cactus and the cochineal break their bounds, both figuratively and materially, moving across borders, slipping from crop to invasive pest, from domesticated to wild and back again, they shine a light on how meaning—and language, as a tool of meaning-making—is unstable and variable. Neither the cactus nor its associations can be contained. In Mexico, the cactus pads are seen as a culinary delicacy and the cochineal a prize, both instrumental in retaining food and land sovereignty against the Spanish empire.

Connecting this knowledge from Mexico to Palestine, these practices illuminate how the cactus and the recent spread of cochineal across the Mediterranean can counter colonial land uses and Western visions of Palestinian landscapes. Growing the cactus for food, cultivating hedges for security and evidentiary testimony, and using the dried cactus fibers as a building material are acts of defiance, resilience, and intentional reclamation of local plant matter to resist colonial erasure. Integrating the long legacy of using the carmine red of cochineal’s pigments in Latin America with traditional Palestinian practices of embroidery and weaving maintains and sustains a shared connection to the land.

As a collective of three, each living in different countries and with our own specializations and backgrounds—architecture, writing, photography—our work inherently moves across various disciplinary and geographic boundaries. Mostly coming together for fieldwork or residencies, we center interpersonal and communal relationships, learning from those communities who live with both species, and thinking and working with them on developing new forms of cohabitation and care. While the focus of this essay is on making visible the insidious and intertwined colonial logics that have defined both species, it is important to bring in the communal and interpersonal dimensions of our work through conversations, written accounts, and images of our encounters in the field.

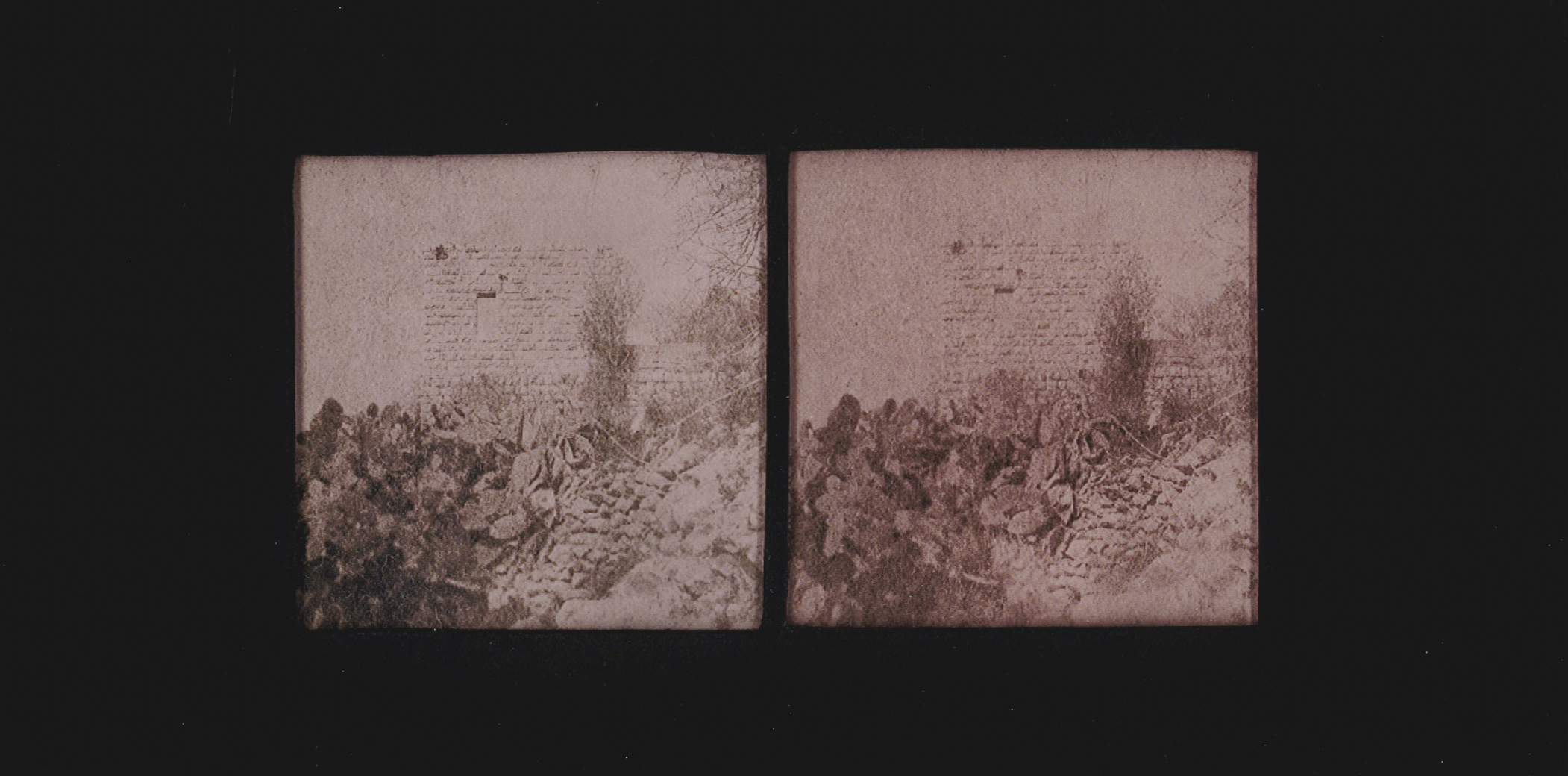

Many of the photographs in this essay were produced during our fieldwork in Palestine in 2023. They depict intimate encounters with cacti across sites of villages destroyed and depopulated in 1948 to contemporary farms and urban spaces in the West Bank. Printed with cochineal that populates these sites, these stereoscopes reference a nineteenth-century image-making technique that creates a three-dimensional effect when looking through the stereoscopic viewfinder. By placing two skewed images of the same scene side by side, the brain fuses the images together, creating a sense of depth and distance, tricking the viewer into an illusion of reality.11

The appeal of stereoscopes “could be regarded as stemming from a deep-seated Western desire to erode the gap between the viewing subject and non-local object,”12 achieving immense success with Western audiences during a period of marked globalization and colonialism. This embodied viewing experience promised access to far-off sites, but did so at the “cost of ripping the viewed scenes from their context”13 and reinforcing the colonial gaze—a field of vision productive of exploitation and ecological degradation—giving rise to stereoscopes of a reimagined Palestinian landscape that propagandized imperial, orientalist, and biblical terraforming agendas.

Image-making with cochineal subverts and disrupts the narrative embedded in colonial imagery that aims to normalize dispossession and genocide; instead, it naturalizes resistance. These re-created stereoscopes offer a counterhegemonic documentation and presentation of land stewardship and productivity, using the cochineal red pigment to recalibrate the human imaginary by making images with the land and of the land—an indexical image in its very materiality—that blocks its intended three-dimensionality. This act of visual resistance continues a tradition of using the cactus as a symbol of rootedness and patience; holding histories, memories, and resiliency within its thorns.

Red Threads from Mexico to Palestine: Cochineal, Common Land, and Colonial Entanglements

Sitting in his office in El Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, Doctor Huemac Escalona Lüttig speaks of the parallels between the struggles against colonialism in Palestine and Mexico, and the pivotal role the cactus plays in both contexts. “Just as the cactus hedges are ‘rebuilding’ the destroyed Palestinian villages as they grow back, and retracing the Palestinians’ presence on the land, Oaxaca City was also built with cactus,” referring to the blood money that the Spanish settlers generated through the trade of cochineal. “Albeit subtle, there is a thread here that connects spaces, territories, people, cactus, and cochineal.”14

The cactus made its way to the Mediterranean—and eventually Palestine—via the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (modern-day Mexico) in the early half of the sixteenth century; a brutal reign of terror carried out across Latin America in search of gold and silver to fund Spain’s many wars and political campaigns. Viewed by the Spanish purely as a host plant for cochineal, the cactus’s value was secondary, insignificant even, beyond its role in the production of rich carmine dyes. In medieval Europe, red—the color of desire, of Christ’s blood, of cardinals’ robes—became a way for kings to demonstrate their God-given right to rule, and, as such, quickly grew as a symbol of not only royalty but also social status and wealth.

As dyers’ guilds across Europe were tirelessly trying to find the recipe for dyeing fabrics the brightest, longest-lasting, and most brilliant red, Spanish merchants encountered the intricate fabrics and vivid pigments across the Indigenous marketplaces of recently colonized Mexico—or New Spain, as it was known at the time—dyed with an insect unheard of in the Old World. Known as nocheztli—meaning “the blood of the cactus”—among the Aztecs, by the nineteenth century, cochineal would become the most valuable agricultural export in the world by weight. It built cities in Spain and across the colonies on its blood gold.

Searching to better understand Indigenous relationships to both species, in March 2024, we traveled to the state of Oaxaca, the historical center of cochineal production in Mexico from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. We undertook extensive fieldwork there to learn more about the region’s dye-making practices that predate Spanish rule. As Alejandro de Avila Blomberg, the director of the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, explained to us, over 70 percent of the land and natural resources in Oaxaca are not in the hands of the government, nor the private sector, but are collectively owned under a tenure system called tierras comunales.15 This is the product of a colonial Spanish system, whereby Indigenous communities were authorized to cultivate their own crops and manage their own lands as long as they also paid a percentage to the settlers as tribute. Considering that, in most parts of Latin America, these land rights were encroached on by settlers, mostly Spaniards—dispossessing locals over centuries until the majority of the land in these areas went to private, non-Indigenous hands—how is it that Oaxaca has retained such a large percentage of its land and natural resources under communal tenure?

Alejandro, together with his collaborator Carlos Sanchez Silva, attributes this in large part to the cultivation of cochineal, or grana fina. Maintaining an Indigenous slave population for biological commodities, such as cochineal, was impractical and expensive for the conquistadors.16 In the first few decades of Spanish rule, it was largely ignored as a crop, in part because of the painstaking nature of cochineal cultivation and the difficulty of translating it into a colonial plantation-style system, used elsewhere in colonial empires with crops such as tobacco, chocolate, and sugarcane. Amy Butler Greenfield, in her book A Perfect Red, similarly claims that “far from showing economies of scale, cochineal seemed to do best when grown on family plots, perhaps because only small-scale growers had the patience and personal incentive to give it the painstaking attention it needed.”17 The forms of care necessitated by the intricacies of cochineal production—specifically patience, of which the colonizers had none—together with the Spanish state granting Oaxaca the monopoly on cochineal production for many centuries, provided fertile ground for alternative modes of land ownership to take root.

During our time in Oaxaca, we visited Nocheztlicalli, a family-owned museum dedicated to the cultivation of grana cochinilla fina, which not only includes the practice of growing and harvesting the insect but also the cultivation of the knowledge, wisdom, and community surrounding these practices. For over fifty years, Maestra Catalina Yolanda López Marquez and her daughter Maestra Claudia have dedicated themselves to the preservation and dissemination of traditional knowledge around the farming and use of grana fina in dyeing practices, as well as innovating techniques themselves. The nopaloteca technique for growing and harvesting cochineal was pioneered by Maestra Catalina at Nocheztlicalli and has since become one of the most widely used methods for cultivating cochineal all over the world. By hanging cactus pads in rows in an indoor greenhouse, the result is like a library, but of cacti, not books. The generational inheritance of knowledge and practices such as these—once common—is now concentrated in archival and educational initiatives like Nocheztlicalli, whose patient and insistent passing on of such knowledge is an essential component of the cultivation process.

While the insect has been foundational to securing land and food sovereignty in Oaxaca in the face of brutal colonization, in Palestine—and more widely across the Mediterranean basin—the insect is considered a threat to the prickly pear cactus, and thus a threat to the land and food sovereignty of Palestinians, as many rely on the cactus for protection as a hedge plant and for food in the form of its fruit. Interestingly, even in Oaxaca, discourse around what is/is not invasive/native, wild/domesticated, pest/crop, still plagues the cochineal. In fact, these dichotomies are key to understanding people’s relationship to both species, on either side of the Atlantic. These contradictions—stored in the cactus and the cochineal, much as they store water or carminic acid—are the scars that make visible their long and complicated histories. It is not our job to smooth these blemishes—to reconcile these contradictions—but to draw attention to them, to be spectators to what these marks have to tell us about the violence of colonial logics.

The vulnerability of cochineal stems, in part, from its long process of domestication, enmeshed in Mesoamerican culture. As with any species, domestication makes a living being reliant on systems of human-led care, without which they would not be able to survive. Domesticated over thousands of years, grana cochinilla fina is much larger in size and contains a considerably higher percentage of carminic acid (around 17-24 percent) than its wild counterparts (which average around 11 percent), generically called grana silvestre (or wild cochineal).18 While producing larger and higher-quality yields of pigment, the domesticated grana fina is far more vulnerable to predation and fluctuations in humidity and temperature due to its lack of a protective waxy coat, making the hardier wild species grana silvestre more prolific.

While grana fina is revered as a near deity among Indigenous communities in Mexico, with many families reciting prayers or incantations for a bountiful harvest,19 its wild counterparts receive quite the opposite treatment. Talking to us about the painstaking work of removing grana silvestre insects from her outdoor nopalera, Maestra Catalina referred to these wild relatives of her prized grana fina as pests, a plague to be kept at bay. It is curious, then, that such different language should be used to refer to the genetic ancestors of one of their most prized crops. At the end of the day, it evidences the ways in which the category of invasiveness is primarily an economic one, serving first and foremost to single out and target wild species that threaten the well-being of domesticated crops, no matter the context.

Scholarship on “the commons” is typically dominated by Western discourse and Eurocentric narratives, which center the British Enclosure Movement—the gradual privatization and dispossession of common land across Britain that took place from the twelfth century onward—and the ongoing struggles for roaming and land rights in the United Kingdom. US ecologist Garrett Hardin’s 1968 essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” explains the devastation of common land as a direct result of the commoner or herdsman’s self-interest.20 What political scientist Elinor Ostrom has argued, in opposition to this, is that the actual self-interest propelling the gradual destruction of the commons is that of the government seeking to solve the problem of the depletion of their ecosystems through increased financialization and centralized control.21 It is upon us, therefore, to decentralize this discourse and root our own conversations in the knowledges of communities in the Global South, such as those across Oaxaca and Palestine, where common land practices are modes of decolonial resistance and sovereignty, preserved by the patience of both the human and more-than-human in the face of historic and continuing oppression.

Living Memorials: Sabr Hedges Beyond Colonial Imaginaries of Palestine

A farmer in Gaza overlooks vast agricultural lands in a stereoscope22 taken over a hundred years ago by Underwood & Underwood, an American photography studio that capitalized on images of the Holy Land for Western consumers and archived at the Library of Congress. A closer look at the photograph reveals prickly pear cactus hedges marking the edges of these fields, delineating their boundaries.23

While the first use of cactus hedges in Palestine remains unknown, the practice of land division dates back to the 1858 Ottoman land code. This code targeted communal ownership forms locally known as masha’, replacing them with private ownership to enhance productivity and taxability—hallmarks of the Ottoman Empire’s modernizing efforts in its waning years. The code heavily focused on miri (state) land, the largest revenue-producing land category.24

In the process of implementing these land reforms, demarcating land became crucial for ensuring productivity and keeping livestock separate from crops. In Palestine, cactus hedges were widely used to achieve these goals; however, these fruit-bearing hedges transcended their practical function as boundary markers. Harvesting and eating the cactus fruit often turned into social gatherings, with neighbors sharing fruit. Through this communal sharing, the cactus hedges became more than just boundaries; they symbolically and practically resisted the fragmentation of land imposed by the Ottoman Land Code, maintaining a sense of commonality.

These communal practices and connections were violently disrupted following the 1948 Nakba. Beyond the mass dispossession and destruction of Palestinian villages, ecological campaigns sought to obscure the material traces of Palestinian presence.25 The Aleppo pine, celebrated by Zionist botanists for the ways it resembled forest trees in Europe, was introduced as the dominant species in afforestation projects by the JNF. Framed as an effort to “restore” a biblical landscape purportedly once lush with forests but later abandoned and made “barren,” these afforestation projects concealed demolished Palestinian villages under layers of European-inspired greenery.26 This transformation was not only physical but deeply ideological, reflecting Western visions of the “Holy Land” as a land of biblical promise awaiting redemption. These imaginaries were constructed and heavily propagated through Western literature, photographs, paintings, illustrations, panoramas, travel guides, maps, and artifacts from expeditions and religious pilgrimages between the 1850s and 1940s.

Without ever having to set foot in Palestine,27 stereoscopes, for example, “promised the home viewer a tangible encounter with the Holy Land.” Sold as box sets, each numbered stereoscope corresponded to a detailed map delineating “the sacred terrain traversed by the cards.”28 The images were also accompanied by captions “focused on relating the landscape of Palestine to biblical events and drawing ethnographic comparisons between the people of the Holy Land and those of scripture,”29 creating an imaginary of Palestine as stuck in the mythic past, where land remained “uncultivated” and the people “uncivilized.”

The “sacred landscape,” shaped ideologically and visually by these Holy Land productions, justified imperial terraforming agendas to “make the desert bloom.”30 As Danika Cooper observes in “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” landscape images can become instruments of imperial violence to legitimize colonial agendas:

As landscapes are eternally made and remade through temporal, environmental, and anthropogenic processes, landscape images are themselves agentic forces in this making, responsible for producing new forms and visions. Thus, landscapes and their images are also engaged in a recursive relationship—actively making and remaking each other. When images are leveraged as instruments for an imperial project, the visual archive reinforces, legitimizes, and reproduces violence through its visual language of codes, signifiers, and hierarchies.31

In resistance to the uprooting of Palestinians and their landmarks and the terraforming of their lands with newly introduced forests, the cactus hedges have since become vital markers—ecological testimony—of destroyed Palestinian villages. As they regrow from stubborn roots deeply embedded in these terraformed landscapes, they evidence the properties of those whose lands are stolen, becoming a common code for Palestinians in the 1948 territories: where cactus plants thrive in a forest or uninhabited fields, a village once stood.

Palestinian artists from across historic Palestine incorporate the cactus into their work as a symbol of rootedness and resistance under a settler-colonial regime. Western landscape aesthetics—such as those applied in the stereoscopes—often create distance between the viewer and the land and separate foreground from background; artists Walid Abu Shaqra and Asim Abu Shaqra break this convention. Walid’s work treats every element of the landscape, whether tree, stone, or cactus hedge, with equal significance, each symbolizing the enduring presence of the uprooted Palestinian people. Asim’s art takes this further, portraying the cactus as a metaphor for displacement. His recurring depiction of a potted cactus—uprooted from its natural habitat and confined to an urban setting—parallels the Palestinian experience of dispossession. Just as the cactus hedge signifies the patience of the land waiting for its people, the potted cactus embodies the patience of a people awaiting their return to their lands.32

On the drive through the Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem, Palestine, the cactus appears in wall graffiti alongside the key of return and landscapes of olive trees. These images recur in Land Day posters, protest materials, political magazines’ front pages, and in oral history maps of destroyed villages, signifying how ingrained the cactus has become in Palestine’s popular culture, even in exile, as a symbol of rootedness and resistance.33 In a Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) poster featuring a child’s drawing from 1980, a cactus grows into a freedom fighter, blurring the line between the Palestinians and their land from which they draw their patience and strength to resist.34

Emerging from the (H)edge: Acts of Renewal and Resistance

The withering pads of a cactus hedge, once planted in Rweis village, Haifa, before its destruction in 1948, have fallen to the ground, weakened by the clusters of cochineal draining its water. Yet, from the cactus’s decaying carcass, a new pad emerges. It resists our attempt to lift it. Roots have already begun to take hold beneath the soil. Beside it lies a large dried cactus trunk, its peeling layers of fibrous mesh revealing new material possibilities.

In recent years, many of the cactus hedges in Palestine are on the verge of disappearing once again, this time from the spread of the false carmine cochineal (Dactylopius opuntiae), which feeds and dwells on the cactus, slowly killing the host plant in the process. Tracing the false carmine cochineal’s arrival to Palestine reveals additional layers of colonial legacy embedded in botanical practices. Between the 1920s and 1940s, the insect was introduced to settler colonies such as Australia and South Africa35—where the cactus is considered an invasive weed—to biologically control the prickly pear populations that rendered large areas of agricultural and grazing fields unusable.36 While this new strain of cochineal was considered a savior by white settlers,37 it is now regarded as a pest in the Mediterranean basin, where it eventually made its way.

It is uncertain what caused the cochineal outbreak in the Mediterranean region.38 What is certain, however, is that every time the cactus and the insect have moved across geographic and cultural borderlines, so too have the perceptions of them shifted and moved. Pest and crop, wild and domesticated, plague and protector: these diverging ideas reveal how categories of value and belonging in nature are constructed to protect human interests, often tied to economic, imperial, or colonial logics far removed from life on the ground.

What, then, can we learn from species that escape domestication, that break their boundaries, that rewild themselves and form new ecologies? These remnants of wildness, like the cochineal and the cactus, survive uprooting and evade control; they bear the traces of previous domestication and memorialize histories of dispossession. As we grapple with their current status as both “pest” and protector, they remind us of the layered relationships between land, more-than-human beings, and power, challenging us to rethink not only what we have lost but what continues to resist and regenerate in and from the margins.

The farmers we met in Ein Qiniya, Bil’in, and Tamra villages in Palestine have learned from the cactus. They have learned the ways in which it withers, resists, and regrows after a disturbance; that periodic pruning, which allows sun and air into the plant, deters cochineal from thriving in the moist, damp, dark undercarriage of the hedges; that harvesting cochineal from the cactus pads similarly helps the plant to survive while simultaneously holding potential for new artisanal practices to emerge from the use of its brilliant red pigment, such as through producing dyes for textiles or ink for printmaking.

In Oaxaca, the cultivation and use of cochineal has significantly decreased in recent generations, with the advent of cheaper and easier to obtain artificial dyes. Maestras Catalina and Claudia’s life work at Nocheztlicalli is to preserve and teach cochineal cultivation to local dyeing families, many of whom have shifted to the use of artificial dyes or to buying cochineal in bulk from small-scale commercial producers instead of growing it themselves. Their work has reintroduced a near-extinct artistic practice into local crafts. A number of Mexican artists, such as Edgar Jahir Trujillo, explore cochineal as a medium for addressing Oaxaca’s colonial past and Indigenous resistance through these deeply rooted material practices. In the right context, cochineal can be a powerful vehicle for image- and meaning-making.

Similarly, the images accompanying this text use the red pigment to situate the cochineal within the land, as part of the land. They emerge from a tedious and time-consuming process, and are, in and of themselves, a lesson in patience. The photographic negatives made in Palestine were exposed to paper layered with a light-sensitive cyanotype solution to create positive prints, each print taking up to thirty minutes to expose. The Prussian blue hue of the cyanotype was later extracted, bleaching and erasing the image entirely. After the paper is placed in a tea bath with cochineal pigment, which has to be continuously refreshed, the image develops and reappears.

Rather than the cochineal destroying the landscape, it re-creates it, becoming enmeshed in the image-making process. The red dye of the cochineal forms and integrates into the materiality of the image, resulting in prints that counter the landscape as “seen, not touched.” The images are imperfect, slightly blurred and porous, shifting the highly stylized and technically accurate creation of the camera to a collaboration with the land, working to represent itself. No two prints are identical, making it more difficult to create the three-dimensional effect of the stereoscopes. The illusion of reality is undone by the cochineal, touching on the immense loss these lands experience through the West’s violent gaze and speaking to the emergence of new forms of patience in the land.

This threshold between disappearance and regeneration pushes us to look for “all that remains”39 when the more-than-human appears to be unraveling. It is in the remnants left behind—the regrowth, the dried fibers, the cochineal pigment—that we begin to see potential not just for survival but for renewal and resistance. Sabr, inhabiting the verges between loss and regrowth, redraws the boundaries of what has been lost. Its inherent borderlessness—regenerating after a disturbance, entangling with new lands and ecologies, carrying the memory of its people across cultural and political edges—nourishes those who remain patient in the face of erasure and inspires emergent forms of community and commonality.

-

Mahmoud Awadia (@mahmoud_awadia), “As much as we have been patient, we have eaten patience with its thorns,” Instagram post, February 26, 2024, link. ↩

-

This photosynthetic process is called crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). These plants conserve water by opening their stomata at night to absorb carbon dioxide and closing them during the day to avoid evapotranspiration. During the day when light is available, they convert the stored CO₂ into sugars by photosynthesis. Sung Don Lim et al., “Laying the Foundation for Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) Biodesign: Expression of the C₄ Metabolism Cycle Genes of CAM in Arabidopsis,” Frontiers in Plant Science 10, no. 101 (February 2019), link. ↩

-

Shukri Arraf, Land, Human and Labor: A Study of Our Material Culture on Our Land (Shukri Arraf, 1993). ↩

-

The Jewish National Fund was established in 1901 as the product of the congresses of the World Zionist Organization held in Europe in the last years of the nineteenth century. It was the Zionist institution responsible for purchasing massive tracts of land in Palestine and developing it for settlement by the Jewish community. Today it is a quasi-governmental body largely responsible for planting and managing forests in Israel. ↩

-

In Forensic Architecture’s investigation “Execution and Mass Graves in Tantura, 23 May 1948,” the cacti growing at the site played a crucial role in locating and identifying the mass graves following the massacre committed by Zionist militias in the village of Tantura in 1948. See “Execution and Mass Graves in Tantura, 23 May 1948,” Forensic Architecture, link. ↩

-

Ailo Ribas, Areej Ashhab, and Gabriella Demczuk, “Hedge-Riders: On the Entangled Ecologies of Palestine’s Fading Cacti,” Awham Magazine: The Plant Issue, no. 6 (2023): 26. ↩

-

Ribas, Ashhab, and Demczuk, “Hedge-Riders,” 26. ↩

-

Alejandro de Avila Blomberg, discussion with the authors at the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, March 26, 2024. ↩

-

Recent projects explore cochineal use in Palestinian crafts, including Nol Collective’s work, which seeks to revive traditional Palestinian dyeing practices by combining locally sourced cochineal with madder root to create natural dyes. Their work highlights a broader cultural effort to reconnect with Indigenous dyeing techniques using regional plants and natural sources. In our 2023 workshops at Sakiya, Ein Qiniya, we also explored the use of cochineal in dyeing, printing, and image-making, by inviting Palestinian artists, dyers, and weavers to rethink cochineal as a newly available natural resource rather than merely as a pest. Nol Collective, “Nol Collective - Meet the Photo That Catalyzed Months of Research,” Facebook, 2023, link; Al-Wah’at Collective, “Wild Hedges – Arts Catalyst,” Arts Catalyst*, June 21, 2023, link. ↩

-

The exact timeline of when the first outbreak of cochineal occurred in the Mediterranean, and where it stemmed from, is hazy, with people giving varying accounts. But they all fall between 2007 and 2014, and agree that the spread of cochineal originated in its introduction as a biological control agent to curb the spread of the cactus. Gaetana Mazzeo et al., “Dactylopius opuntiae, a New Prickly Pear Cactus Pest in the Mediterranean: An Overview,” Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 167, no. 1 (January 2019): 59–72, link. ↩

-

In his essay “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” published in The Atlantic in 1859, essayist and stereoscope inventor Oliver Wendell Holmes writes about using the stereoscope for the first time: “The first effect of looking at a good photograph through the stereoscope is a surprise such as no painting ever produced. The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture. The scraggy branches of a tree in the foreground run out at us as if they would scratch our eyes out. The elbow of a figure stands forth so as to make us almost uncomfortable. Then there is such a frightful amount of detail, that we have the same sense of infinite complexity which Nature gives us.” Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” The Atlantic, June 1859. ↩

-

John Plunkett, “‘Feeling Seeing’: Touch, Vision and the Stereoscope,” History of Photography 37, no. 4 (2013): 389–396, link. ↩

-

Oliver Wendell Holmes describes the aim to produce stereographs of “every conceivable object of Nature and Art.” He compared this quest to a game hunt where photographs are to photographers what animal skins are to hunters, reinforcing the colonial mentality of image production as conquest and domination. Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph.” ↩

-

Huemac Escalona Lüttig, discussion with the authors at the Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca, March 26, 2024. ↩

-

Alejandro described how Spanish colonizers refrained from enforcing a plantation-style system on many Indigenous communities across Mexico primarily due to the geography, climate, and nature of local crops. Instead, the lands were communally owned under Indigenous land rights issued by the king of Spain. Blomberg, discussion with the authors, March 26, 2024. See also Amy Butler Greenfield, A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire (HarperCollins, 2006), 19-22. ↩

-

Blomberg, discussion with the authors, March 26, 2024. ↩

-

Greenfield, A Perfect Red, 91–92. ↩

-

Cristóbal Aldama-Aguilera et al., “Cochineal (Dactylopius Coccus Costa) Production in Prickly Pear Plants in the Open and in Microtunnel Greenhouses,” Agrociencia 39, no. 2 (March 2005): 161–171, link. ↩

-

Paul F. Bufis, “The Sacred Prayers of the Cochineal Ritual,” Alcheringa: Journal of Ethnopoetics, no. 3 (Winter 1971): 16–32, link. ↩

-

Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, no. 3859 (December 1968): 1243–1248, link. ↩

-

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 216. ↩

-

Underwood & Underwood, “Gaza, lowland stronghold of the Philistines, from the southeast, Palestine,” circa May 8, 1911. Copyright Underwood & Underwood. Courtesy of Library of Congress, link. ↩

-

Nasser Abufarha, “Land of Symbols: Cactus, Poppies, Orange and Olive Trees in Palestine,” Identities 15, no. 3 (May 2008): 343–368, link. ↩

-

Shaul Ephraim Cohen, The Politics of Planting: Israeli-Palestinian Competition for Control of Land in the Jerusalem Periphery (University Of Chicago Press, 1993), 35–36. ↩

-

Of the 150 forests managed by the JNF, 46 forests cover ruins of 89 Palestinian villages— 87 destroyed in the Nakba and two in the 1967 war. Eitan Bronstein Aparicio, “Most JNF - KKL Forests and Sites Are Located on the Ruins of Palestinian Villages,” April 2014, link. ↩

-

Areej Ashhab, “Invading Landscapes: The Biography of a Tree in Palestine,” in Border Environments, ed. Riccardo Badano et al. (Centre for Research Architecture, 2023). ↩

-

Holmes writes of this “arm-chair” experience: “I pass, in a moment, from the banks of the Charles to the ford of the Jordan, and leave my outward frame in the arm-chair at my table, while in spirit I am looking down upon Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives.” Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph.” ↩

-

“Global Vistas: American Art and Internationalism in the Gilded Age—Stereocards,” Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, 2020, link. ↩

-

“Global Vistas: American Art and Internationalism in the Gilded Age—Stereocards.” ↩

-

The phrase “make the desert bloom” became a central slogan in the Zionist movement, rooted in settler-colonial ideologies that justify the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by portraying their land as barren and neglected. This rhetoric has celebrated the transformation of these lands into “productive landscapes” through modern agricultural techniques and Jewish labor, driving large-scale interventions such as water diversion, afforestation, and monoculture farming. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was a prominent proponent of this vision, particularly advocating for the settlement and transformation of Southern Palestine (also known as Al-Naqab) as central to Israel’s nation-building efforts. These practices continue to disrupt local ecosystems and sever Palestinians’ access to their lands and resources as part of a broader Zionist strategy of erasure and domination. Nur Masalha, The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory (Routledge, 2014). ↩

-

Danika Cooper, “Drawing Deserts, Making Worlds,” in Deserts Are Not Empty, ed. Samia Henni (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2022), 81. ↩

-

Kamal Boullata, “'Asim Abu Shaqra: The Artist’s Eye and the Cactus Tree,” Journal of Palestine Studies 30, no. 4 (July 2001): 68–82, link. ↩

-

The Palestine Poster Project Archives, “Iconography: Cactus,” Palestine Poster Project Archives, 2014, link. ↩

-

Ilham Shahrour, A Palestinian Militant, 1980. ↩

-

Mazzeo, “Dactylopius opuntiae,” 59–72. ↩

-

Alan Parkhurst Dodd, The Biological Campaign against Prickly-Pear (Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board, 1940). ↩

-

William Beinart and L. E. Wotshela, Prickly Pear: The Social History of a Plant in the Eastern Cape (Footprint Press, 2021). ↩

-

Was it a direct result of its previous introduction to South Africa and Australia? Was it the result of cochineal being introduced to another country in the region, more recently? Was it the result of poor phytosanitary management of agricultural imports? “La Consejería intensifica la lucha contra la cochinilla silvestre de las paleras,” La Verdad, March 17, 2008, link. ↩

-

All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 is a canonical text by the Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi that describes 418 Palestinian villages that were destroyed or depopulated in the 1948 Nakba. The cactus is present in many images included in the book, bearing witness to the histories of the Palestinian villages and their people. Walid Khalidi, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992). ↩

Formed by Ailo Ribas, Gabriella Demczuk, and Areej Ashhab in 2022, Al-Wah’at is an artist research collective committed to countering harmful anthropocentric and colonial narratives around arid lands and futures. They engage with a diversity of communal practices and knowledges—local, folk wisdom, scientific, translocal, more-than-human—to create a more holistic understanding of these ecologies, particularly in light of climate change. Their award-winning project Wild Hedges, started in 2023 at the Sakiya organization in Ein Qiniya, Palestine, as part of the Soil Futures residency program, investigates the ecological and sociopolitical complexities of the prickly pear cactus and the cochineal insect across various geographies, communities, and temporalities. Al-Wah’at has also contributed to several publications, including “A Living Memorial” (2023) in Stuart, no. 2 and “Hedge-Riders: On the Entangled Ecologies of Palestine’s Fading Cacti” (2023) in Awham Magazine, no. 6. Wild Hedges is supported by Prix COAL, the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, and Anhar: Climate and Culture Platform, a collaborative initiative between Art Jameel and the British Council.