I default to thinking of gardens as feminine terrains, perhaps because of memories of my grandmother, her tending to and laboring in her garden in Miami—an intimate space she carved out for us to enjoy beautiful flowers. Or maybe it’s because gardens are often tethered to homes, and matters of the home and hearth have been naturalized as a woman’s domain. I remember my grandmother emphasizing the soothing power of her garden. I remember her telling me stories in the kitchen while slicing papaya, avocados, tomatoes, plantains, and cassava. Papaya was for preventing cancer and tumors. Okra was for hydration. Tomatoes were for the skin. Aloe was used on bug bites, odd rashes, burns, and hair. Castor oil was for hair growth and inflammation. Cloves were used for dental problems. Lemongrass for insomnia. Garlic, ginger, and oregano for immunity. Nothing compared to the routine of her strolling in with boxes of tomatoes. She had a statue of La Virgen de la Caridad watching over her yard. Her garden was a space of spirit, creation, and beauty. I write of her garden today because this small plot of land was her domain—not her property, but a space where she could truly teach me. Without explicitly articulating it, she taught me that the garden was a space for food abundance and medicinal healing, for mental reprieve; it was an ecopoetic project. She expanded her garden in Miami as an exercise of memory in ways that deepened my environmental consciousness, recalling the gardens of other Americas—in the Caribbean, in Cuba, and in Haiti. My Cuban grandmother gave me a way to think about myself and my belonging to land.

This essay not only serves as a record of the women I’ve witnessed in my life who transcend and obtain beauty under dominance; it documents the magic of my mother and grandmother’s kitchen, cabinets, and gardens, of their leveraging objects and land to create a more beautiful life for themselves and their children. I learned the theoretical principles of decolonization from both my grandmothers’ resilience in Cuba and Haiti. Through its scale and alterability, the garden was a particularly affirming space for this Afro-Indigenous knowledge as emancipatory practice. Miami offers a different way of thinking about Black geographies. I introduce my heritage within conjure feminism to present Miami as a space to think through ownership, especially in the face of climate gentrification. Conjure feminism is defined as textual and generational knowledge of Black women’s spirit work, including Root, Vodou, plant medicine, cooking, gardening, or ethnobotany as ancestral practice.1 It emerges from the practitioner’s knowledge rather than focusing on the power or implications of the animating spirit. Heritage, then, is defined as a material property that may be inherited or a spiritual possession. I’m interested in conjure feminism as heritage because of the subversive ways Black and Indigenous women could use the land to recast their relationship with space and society before and beyond colonization. Embracing Black studies offers a lens to read this space and its people, one that embraces the magic: the conjure practices that Afro-Indigenous people used to survive and point to modern conjurings in hopes of starting a broader conversation about belonging, stewardship, and indigeneity.2 Ultimately, this essay calls for conjure spaces such as conucos and botánicas to be legally protected as heritage sites.

This essay grapples with the challenge of looking toward and beyond unspeakable violence, rhetorical erasure, and epistemological destruction that draw Taíno and African peoples into intimate kinship through shared experiences of conquest and slavery in the Americas, while also looking toward their transcendence as solutions toward a freer future. Conjuring is interpreted here as shared practices of resistance, refusal, building, intersectionality, and intermarriage that Black and Indigenous folks have stewarded through land, spirit, and knowledge production.3 Within this work, I consider the ways conceptual and material lands have been appropriated and dispossessed as a means of reinforcing human and spatial hierarchies. This essay uses conjure feminism to advance a conversation about Caribbean American placemaking that unsettles Western conceptions of heritage and ownership.

The Remnants of the Taínos in America

My grandmother’s home was a curation of global history. Her cabinet was akin to a shrine, housing African effigies disguised as Catholic saints, tall ebony wood sculptures, postcards of Jesus, wine glasses full of holy water, and porcelain dolls. Through these objects, she introduced me to the subversive dimension of the home. She spoke fondly of her Catholic school days in Cuba, though she also collected and venerated African saints. In doing so, my grandmother visualized for me the African and Indigenous fungibility4 and the untenable bond that African, Indigenous, and European-descended people share through creolization.5 I do not know if she fully recognized the power of those lessons of relationality. It did not matter whether she could articulate the political significance of this subversive tactic; what mattered was that she freed me to understand the importance of belief and struggle. By positioning images and/or objects in space, she reworked the home not only as a space of agency and subversion but also as a space of belonging. Her suburban house became alterable through her exercise in signification, and in moments, I caught glimpses of Cuba and Nigeria. My grandmother gifted me the knowledge of plant medicine, cooking, and gardening as ancestral practices of conjure feminism.

My grandmother’s gardening was connected to a larger, though underdocumented, Afro-Indigenous land practice that exists throughout Miami. The conuco, or Cuban home garden, is one of the best-preserved traces of Haitian-Taíno heritage due to a long history of exchange and migration between the islands of Haiti and Cuba. The Taínos taught the Haitians agriculture and, upon immigration, shared this knowledge with the Cubans. Conucos typically have a radial plan anchored by a small house at its vertex with trees functioning as a “living fence.” These gardens were essential to subsistence, medicine, and spirituality. A conuco garden often includes guanabana, Spanish lime, castor oil plants, lemongrass, squash, lima beans, papaya, coconut trees, mango, avocado, guayaba, cassava, wild peppers, coffee, tomatoes, plantains, sweet basil, pineapple, and sugarcane. Many of these same plants and practices are tethered to botánicas, stores that sell medicinal herbs and other spiritual and healing goods. In the Caribbean, these gardens often emerged out of necessity.

Although these Afro-Indigenous gardens are widespread, tethered to many suburban homes across Miami, they receive no state or federal recognition.6 Nor do they engender any local, state, or federal protections for these communities, despite their massive historical and cultural contributions, contributions demonstrated by the host of scientific healing practices that we call Haitian ethnobotany. Though I recognize the contradiction of calling for state recognition of land practices that epistemologically and spiritually exceed it, the urgency of the call is hinged on the speed at which climate gentrification threatens to sanitize Black and brown people from Miami. Legal recognition could potentially preserve foodways and spiritual practices that might otherwise be destroyed. The displacement and erasure of our gardens and botánicas are detrimental to the epistemological preservation of Haitian knowledge and history and to Haitians who have endured alienation in their land and continue to bear the brunt of this legacy of alienation in America.7 In Miami, where many people are displaced immigrants or exiles, vernacular architectures like the conucos and botánicas produce a legible sense of belonging in the built environment. In lower-income or lower-resourced communities, the garden’s function remains twofold: as a means to resolve food insecurity or access to medicine, and as a cultural expression of home plants, religion, gender, or kin.8

Religious syncretism has thrived in the Caribbean because of the many parallels between African and Taíno gods and goddesses and Catholic saints. It functions subversively: strategically veiling existing social structures or previous religious beliefs under the appearance of orthodox religion. African and Taíno deities had biblical counterparts in European Roman Catholicism that allowed for swift “adoption” of the orthodox religion. For example, figures like La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre were surrogates for the Yoruba Oshun, the goddess of beauty, sensuality, and fertility. La Virgen was probably my grandmother’s favorite saint, as she was the patroness of Cuba and had political symbolism. She appears throughout Miami’s domestic and urban realm, at different scales: she is nested in altars in our mothers’ gardens, adorns wine glasses in our kitchen cabinets, and sits on top of our dressers enshrined in gold. This African and Indigenous fungibility can be traced in the imagery of La Virgen. For instance, the upside-down crescent that she stands on in Cuban iconography is derived from crescents in Taíno culture. In a journal entry from 1496, Columbus documents a Taíno man wearing “a half-moon of guany [guanín] and another half-moon of twisted hair and certain small pieces of brass tied together” through the lower part of his nose. The Taínos saw the crescent as a rainbow, associated with their feminine spirit, Guabonito, manifested by the union of sun and rain. Guabonito had an inaccessible sexuality and was linked to healing rites and purgation. The African appeal was her parallels to the Yoruba goddess Oshun, who was often represented in gold and with cowrie shells, thought to have been conjured in water.9 Her image was discovered in 1612 in Nipe Bay by three enslaved boys known as “los tres Juanes,” in which she holds baby Jesus. They took her wet wooden effigy into the town near the copper mines, hence the name El Cobre. In Cuban collective memory, La Virgen is the patron saint who watches over migrants traveling at sea. Her image was used as a historical symbol in the Independence War of 1895 and the Ten-Year War of 1868–1878, which drew in guerrilla warriors from all statuses and was integral in freeing slaves in Cuba. Cuba would not gain independence until 1902.

In the face of gentrification and climate displacement, my grandmother was part of a larger practice of Caribbean women who labored in and embedded their gardens with African and Indigenous knowledge. And so, though this essay reflects on gardening in Miami, it is situated alongside and against other geographies of domination. At the root of this practice is a struggle over space and place, a global struggle against marginalization or subjugation. Privileging new ways of reading reveals the denigration of knowledge we often find in the state, empire, or colony. The restoration of land as a maternal act negates the classificatory imperatives of colonization, where land divisions are drawn up by arbitrary, capitalistic motivations with no regard for the sanctity of the land or subsistence of those who lived there.

A Taíno Reading of America Before Columbus

The frameworks of ownership and property, shaped by savage, hegemonic encroachments of power under slavery and the state, were contingent on visible and reproducible domination, on keeping Africans and Taínos outside the bounds of any recognizable personhood. Most legal rights and traditions concerning property were always structured to support a supremacist, hegemonic framework, with inheritance typically going to a legitimate son. The absence of land or fiscal reparations leaves Haiti in a peculiar suspension, fixed in time as a former slave colony, denied any form of naturalization on the very island it fought to protect.10 The narrative that Taínos are extinct is antithetical to Caribbean-Indigenous epistemologies and ways of thinking. Evidence of Taíno heritage lives on in the utterances of Arawak in Kreyol, pulses through the scratching of güíras,11 the call-and-response of a rueda circle, in the Neg Mawon blowing a conch shell during the Haitian revolution, and in the mango tree anchoring an abuela’s conuco garden.

Claiming Indigenous extinction is a reductionist attempt at robbing the Haitian people of the rights that come with belonging and their due atonement. One of the earliest European records of Taíno life comes from Ramón Pané, a friar commissioned by Columbus in 1498 to record life on the island then called Ayiti, modern-day Haiti. The rhetorical erasure of Indigenous discourse from the literature of slavery is an intentional practice of estranging Haitians not only from their land but also from legal reparations, denying them even rhetorical citizenship. Being Haitian and Cuban, my conception of Indigeneity has always been rooted in both Taíno and African identity, most explicitly through the ethnobotany practices my grandparents passed down to me. I was taught that my relationship with the land was reciprocal; I was indebted to this land that supported me, and the land healed me in exchange for my care. The Taíno reading of Haiti as a living space, despite Pané’s writings, excited me because I had always seen my abuela’s garden as an alive space, so it was affirming to see that conjure feminism has existed in the earliest practices on the island and afforded my ancestors agency.

The foundation of American anthropology, Pané’s writings documented the African and Indigenous people of the island, their appearance, disposition, spirituality, folklore, and their environment. In his writings, Ayiti was a place set in “astral lore, on an island viewed as a great monster of the female sex and that the great cave of Guaccaiarima was her organs of generation.”12 He positions unnamed Taíno people as an amorous young girl, “as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten [years old] now in demand.”13

Framing Haiti as an alive space, the birthplace of America, a female creature, the island whose caves were her sexual organs, shapes the material, conceptual, and rhetorical terrain in which the country exists and by which its freedom and subjugation are made possible. Despite these distortions, the recognition of land as an alive space is central to Haitian culture and epistemology, as well as liberated Black thought. This is confirmed by the early description of Haiti as a living female monster and by the necessity of Vodou in the success of the Haitian Revolution, which was the impetus to freeing the Black diaspora globally as the first free Black republic in the world. Vodou is a monotheistic religion where worshippers connect to a singular god, Bondye, “good god,” where practitioners commune with Bondye through hundreds of lwa, a pantheon of spirits. Each lwa has its ethical codes and could be associated with aesthetic traditions or material cultures, such as drape-making, where colors and form could signify or contain the lwa. In Haitian society, the houn’gan and mambo, the priest and priestess, respectively, require a mastery of plant knowledge as Vodou is a practice of ethnobotany, where plants are used for healing and spiritual purposes, though priest(esse)s also serve political and spiritually revered roles in society.14 Conjuring plays a central role in Haitian society, in its origin stories, ancestral readings, and use of the land, and its modern-day life, through gardening, cooking, and worship.

Though Vodou was illegal in Haiti under colonization until 1987, it has persisted through religious syncretism—the strategic veiling of an intended African spirit with a Roman Catholic saint. To this end, there are layers of creolization integral to understanding Haitian conjuring, which would otherwise be indecipherable to someone without exposure or access to this sacred knowledge. It becomes a more feasible premise that a small African colony of 12,000—of them 6,000 women—could overthrow a colonial power if the maroons had the advantage of finding Haiti’s mountains and swamps legible, understanding Haiti the land as a living, alive entity and reframing it as an active player in its liberation. Vodou was often used for political organizing, as it was famously used at the instigation of the Haitian Revolution, which on January 1, 1804, yielded the world’s first free Black republic.

The political dimension of Black people’s daily practices necessitates acknowledgment and protection; in doing so, we can address the needs of the present and future communities who are grasping for structures of renewal and healing. With the shift in perspective from that which is native to that which is colonized, where paradigms for decent living resemble apolitical conditions of norms, we only further ensure the loss of our cultural diversity and biodiversity, emphasizing my call to protect such practices federally. More specifically, conjure feminist practices problematize the linear definitions of heritage and the hegemonic and colonial definitions of ownership under the state. Reading land as an active, alive space, as my ancestors did and continue to do, upends empirical organizations of land hierarchies. My task is to expand framings of heritage, particularly through the practices of conjure feminism, which have been largely unacknowledged within preservation efforts. My connection to the land was tied to two central questions: How does space articulate and alter human hierarchies? How can Black studies be a rhetorical tool for real land reclamation?

Little Haiti’s Botánicas: An Architecture of Conjure Feminism

Little Haiti is a mid-twentieth-century enclave of exiled Haitians in Miami, Florida. It lies three miles north of Miami’s downtown, encompasses 50 by 10 city blocks, and sits 7 to 14 feet above sea level.15 Little Haiti spans the three historic neighborhoods of Lemon City, Little River, and Edison, where, in the 1950s and again in the 1980s, many Haitians settled as political asylum seekers. In 1980, 25,000 Haitians came to Miami to escape the Duvalier regime.16 They were met with hostility that was compounded by the reaction to the Mariel boatlift, which saw 125,000 Cuban refugees arrive in South Florida, and by the tensions of the 1980 Miami race riots.17

Little Haiti’s housing typically consists of single-family homes and four-to-ten-unit apartment buildings. It seems like Haitians and their architectural aesthetics are vanishing every day. Resting between 54th and 71st Streets, the neighborhood is characterized by narrow streets, colorful buildings, botánicas, and utterances of Kreyol from the elderly surveying the street from their porches.18 Its cityscape is made up of swooping gingerbread facades, A-frame roofs, and tropical hues characteristic of ornamentation found in Haitian vernacular shotgun housing (lakay).

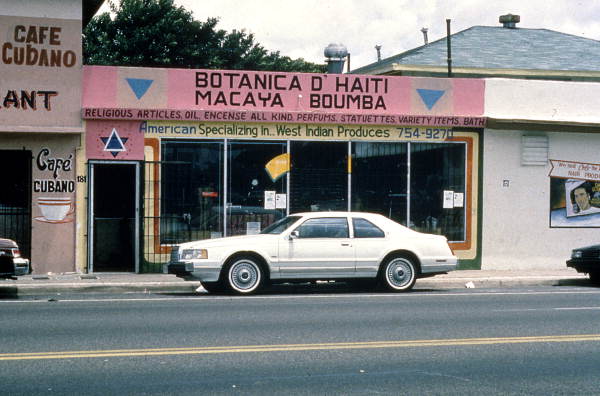

Although Haitians suffered significant social exclusion from Miami’s economy and greater society, Little Haiti has become a developer’s most enticing real estate. The Little Haiti Cultural Complex, designed by Zyscovich Architects and known for high-profile mixed-use retail and residential buildings, is the centerpiece of Little Haiti’s landscape. The complex has a French Kreyol facade with a modern interior and naturally lit, interconnecting exhibition and recreational spaces. Long windowed halls and rooms are used as community spaces for art and education. Its gingerbread and highly ornamental woodwork give it a lace-like quality. It is Victorian profaned by color: bright yellow, cool aquamarine, and igneous orange. Local Miami architect and curator Gustavo Alejandro Garcia reveals the spatial logic of gentrification: “By comparison, the adjacent neighborhoods tend to have a more manicured image, with murals and retro furniture on display. It’s reminiscent of a distant cousin from New York.”19 Garcia describes the visual uniqueness of Little Haiti: “The neighborhood does not try to imitate any other place—not even Haiti. It is… neither here nor there.”20 However, the local muralists, restaurants, bakeries, gardens, and botánicas that used to line 2nd Avenue, the heart of Little Haiti, are disappearing, and along with them, the local Haitian economy. These single-story businesses with hand-painted signage and barred windows are giving way to a market that excludes the community that once built it.

Today, homeownership is unattainable for many lower-income residents in Miami. In Little Haiti, only 26 percent of the population owned homes as of 2016.21 Its home values increased by 19 percent between 2016 and 2020.22 Today, Little Haiti is the ninth most expensive neighborhood for rentals in the country.23 Little Haiti’s high elevation makes it a desirable location for real estate, particularly for those in high-risk geographies, such as Miami Beach. Miami’s known reliance on gravitational flow makes Little Haiti a low-risk geography, and higher-income gentrifiers move into the neighborhood, seeking to capitalize on its topography. Miami’s segregated zoning codes excluded Black people from even entering Miami Beach until 1949, making the targeting of this immigrant community all the more insidious.

We should not be passive in the face of the forces that continue to alienate Black people in their own homes. We should not glamorize a future that further alienates us from land, as is often done with the image of the gentrified city. The cultural landscape of Miami’s Little Haiti expresses the reciprocal relationship between environmentalism and postcolonial migration, as well as the relationship between environment and heritage. Climate gentrification involves reinvesting capital after a period of divestment with consumer preferences based on flood risk or observations of flooding.24 Climate gentrification’s economic methods exploit actual and possible ground rent, made possible by lower-class displacement followed by middle- or upper-class replacement.25 I reread gardening and conjuring as a shared global task among Black people in preserving heritage and, in the case of Miami, redressing the rapid erasure of some of its most significant sites: home gardens and botánicas.

Oppositional Acts of Ownership

Despite the ways Miami evokes or materializes the Caribbean through style, the city also has a long history of rejecting its proximity to Blackness through prejudiced home loan practices, racial zoning, and predatory development practices. To my horror, the botánicas that the public relies on for natural medicine are becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate gentrification. Owning a botánica is one of the few traditional Haitian occupations within the neighborhood. Over half of Little Haiti’s botánicas are owned by Haitians and, for decades, they have relied on and formed transnational and economic links—bringing goods from home to immigrant communities in Miami.26 Botánicas are one of the most legible architectures of Haitian heritage, a monument to the Indigenous and African systems of Vodou. They are shops where one can purchase religious objects to conduct a ritual, which can include effigies, swords, plants, herbs, drapes, and other adornments that are considered sacred.27 Botánicas are also one of the few economies tied to their country of origin. The architecture of the botánica is embedded in the landscape stories of Vodou, Lucemi, and Yoruba.

Little Haiti’s geographic and poetic practices of creating gardens and botánicas offer a set of oppositional acts of ownership, ones that have less to do with conventional modes of possessing property and more to do with claiming and conjuring a historical present in the face of marginalization. Katherine McKittrick refers to the “alterability of land,” that ownership is always alterable; in the case of Miami’s climate gentrification, ownership of property and meaning is shifting away from its local Haitian-Cuban community. McKittrick draws heavily upon Édouard Glissant’s notion of change within the land:

The poetics of landscape, which is the source of creative energy, is not to be directly confused with the physical nature of the country. Landscape retains the memory of time past. Its space is open or closed to its meaning.28

Botánicas, in this sense, become geographic expressions of Glissant’s “poetics of landscape,” signifiers of movement and history. In Poetics of Relation, Glissant offers poetry as a device for a more legible conversation about Black people’s struggle with land. He explains:

The relationship with the land, one that is even more threatened because the community is alienated from the land, becomes so fundamental in this discourse that landscape in the work stops being merely decorative or supportive and emerges as a full character. Describing the landscape is not enough. The individual, the community, the land are inextricable in the process of creating history. Landscape is a character in this process. Its deepest meanings need to be understood.29

Glissant’s writings animate the land by confronting the possessive power of language and revising social and geographic hierarchies through Creolization. Here, Creole expands ways of naming place and self. Creole becomes a method of (dis)possession—of land and space—and for many, a first act toward liberation: a reclamation of history. By challenging English naming (tree becomes pye bwa), Creolization for Glissant is an ontological, epistemic, and linguistic method—not to exoticize mixture but to trivialize the importance of racial and colonial classification.30 Creolization offers a method inherent to the history of all Caribbean islands—with their African, Indigenous, and European heritage—to generalize the hierarchies of racist supremacist structures of domination. With Glissant’s tools, one can read the landscape and recognize oneself and one’s attending practices. The conuco, I argue, is an example of geographic and material possibilities of Creolization.

The historic and present geographies of Miami are colonial. This is evident in Florida’s history of Spanish and American conquest and the erasure of its Indigenous communities, how violence and displacement are part of Florida’s establishment as a site of marronage.31 It is also evident in the erasure of native cultures from the Caribbean and Caribbean American, as well as in public and rhetorical memory. This coloniality is carried and reproduced in the forces of displacement today, in the ways displacement disrupts the relationship between people, culture, and living landscapes. Yet spaces like botánicas and gardens still actively tie Haitian American and Haitian communities together.

Attending to the broader transnational horizons of shared landscapes and traditions reveals their interconnectedness. The daily lives of the Haitian diaspora in Miami closely resemble the daily lives of the people in Haiti, suggesting a continuous engagement in diasporic memory work and experience. This contemporary crisis of climate gentrification and cultural erasure might be counteracted through the recognition of a latent, radical, political feminist dimension that is inherent in the preservation and maintenance of daily traditions. The restricted possibility, or the impossibility, of imagination in the face of brutal displacement is an injustice to people on the margins who are disproportionately subjected to it. For these communities, the ongoing demand to be recognized as legitimate persists.

The botánica transcends the importance of vernacular architecture because it houses the spirited objects of a Vodouyizan’s ritual; it becomes a site of conjuring, the architecture of a possession, connected to the botánicas that appear throughout islands like Haiti, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. Botánicas were especially helpful for Haiti’s post-earthquake economy. Miami’s Little Haiti holds the largest concentration of Haitian businesses in the diaspora worldwide. The cultural necessity for specific products from Haiti helps Haitian business owners in the US, Canada, or France establish a network with other small businesses or farmers in Haiti and potentially leverage their businesses simultaneously. The US and Haitian governments also play a role in facilitating these transnational relationships by allowing duty-free and tax-exemption policies in certain sectors of Haiti’s exports, such as agriculture.32

The disintegration of Miami’s cultural foundation closes the door on possible Black futurist imaginaries by conforming to norms of capitalist urban development and pushing out the built environments of its Black and Indigenous populations. This extends beyond Miami to many of its other connected geographies with histories grounded in Black liberation. The continued presence of botánicas, despite climate gentrification, calls attention to the rapid displacement of Little Haiti’s community, the erasure of Caribbean practices of health and spirituality, and the community’s endurance of these practices. Following McKittrick’s idea of the “speakability” of place, architectural storytelling has the power to claim or dispossess space. Botánicas embed the stories of Africanity, Indigeneity, and the Caribbean within Little Haiti and represent the ecological and material conjuring of Vodou, Yoruba, and Lucemi traditions. Their appearance in these broad Black geographies opens us up to preserve, recover, and steward a culture that could soon be lost to climate gentrification in Miami.

Caribbean people, like many Indigenous communities, have leveraged their land to not only survive but also transcend their circumstances and make it artful. The garden is a feminist, resilient terrain, and in the materiality of women’s lives in Little Haiti, there is a Creole conjuring. Conucos have created other spaces where the Caribbean can be articulated in the American landscape. While existing discourse surrounding Caribbean Americans often focuses on their marginalized conditions, Miami’s Cuban and Haitian communities also create deep bonds with and belonging to land through embodied, generational knowledge. Little Haiti’s botánicas embody a way of remembering; ethnobotany becomes an intentional practice of spirit and a form of reclaiming land. The medicinal practices cultivated in the botánica tie together present-day Miami and the terrain of the Caribbean some 200 years ago simultaneously, tethering spaces of intimacy to broader Black geographies. The walls are archives of botanical heritage, shaped by beliefs in pantheons of Haitian or Cuban saints and the belief in the earth’s capacity to heal. Botánicas are the architectural residue of a spiritual garden, evidence of long-held beliefs, truths, and lore. Material culture is more than the sociology of people and their objects; it is a shared practice of heritage and generational knowledge, a practice and embodiment of aesthetics and ownership.

-

Kinitra Brooks, Kameelah L. Martin, and LaKisha Simmons, “Conjure Feminism: Toward a Genealogy,” Hypatia 36, Special Issue 3: Conjure Feminism: Tracing the Genealogy of a Black Women’s Intellectual Tradition (Summer 2021): 452–461, link. ↩

-

Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). ↩

-

Brooks et al., “Conjure Feminism: Toward a Genealogy.” ↩

-

The term fungible here builds upon Hortense Spillers in “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 65–81; Sylvia Wynter’s “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—an Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 257–337, link; and C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 55–57. They use fungibility as a theoretical term, in particular referencing Black and Indigenous women’s bodies as sites of signification through captivity. I draw on fungibility here to open up a conversation about the deep intimacy and kinship that non-Black and Black Indigenous women share through encounter, involvement, and capture, while also highlighting the obfuscation of Black voices from public discourse as it applies to indigeneity and reparations. ↩

-

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 33–35, 89–95. ↩

-

Miguel Esquivel and Karl Hammer, “The Cuban Homegarden ‘Conuco’: A Perspective environment for Evolution and in Situ Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources,” Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 39 (1992): 11–15. ↩

-

Carine M. Mardorossian, “ ‘Poetics of Landscape’: Édouard Glissant’s Creolized Ecologies,” Callaloo 36, no. 4 (Fall 2013): 983–994. ↩

-

Christine Buchmann, “Cuban Home Gardens and Their Role in Social-Ecological Resilience,” Human Ecology 26 (2009): 705–721. ↩

-

Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of la Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de sciences sociales des religions 117, no. 1 (2002): 37–58. ↩

-

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 65. ↩

-

Lynne Guitar, “New Notes About Taíno Music and Its Influence on Contemporary Dominican Life,” Issues in Caribbean Amerindian Studies (Occasional Papers of the Caribbean Amerindian Centrelink) 7, no. 1 (2006–2007), link. ↩

-

Edward Gaylord Bourne, “Columbus, Ramon Pane and the Beginnings of American Anthropology,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (1906), link. ↩

-

Dan MacGuill, “Did Christopher Columbus Seize, Sell, and Export Sex Slaves?” Snopes, May 25, 2018, link. ↩

-

Mia Matteucci, “Climate Gentrification in Little Haiti, Miami,” Storymaps, January 7, 2023, link. ↩

-

Florida Memory, “The Mariel Boatlift of 1980,” Floridiana (2017), link. ↩

-

Florida Memory, “The Mariel Boatlift of 1980”; Francisco Alvarado, “1981: Miami’s Deadliest Summer,” Miami New Times, August 10, 2011, link. ↩

-

Rob Goyanes, “That Little Haiti Look,” The New Tropic, January 10, 2016. ↩

-

Goyanes, “That Little Haiti Look.” ↩

-

Goyanes, “That Little Haiti Look.” ↩

-

Goyanes, “That Little Haiti Look.” ↩

-

Jesse M. Keenan, Thomas Hill, and Anurag Gumber, “Climate Gentrification: From Theory to Empiricism in Miami-Dade County, Florida,” Environmental Research Letters 13, no. 5 (2018), link. ↩

-

Christian Portilla, “Gentrification Is Pushing Haitians Out of Miami's Little Haiti,” Vice, September 21, 2018, link. ↩

-

Jeremy Bryson, “The Nature of Gentrification,” Geography Compass 7, no. 8, (2013): 578–587. ↩

-

Keenan et al., “Climate Gentrification.” ↩

-

Cédric Audebert, “Spatial Strategies of Haitian Businesses in the Diaspora: The Case of Metropolitan Miami (2001–2009),” Journal of Haitian Studies 19, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 217– 234, link. ↩

-

Audebert, “Spatial Strategies of Haitian Businesses in the Diaspora.” ↩

-

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 150. ↩

-

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 105–106. ↩

-

Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 140. ↩

-

Neil Roberts, Freedom as Marronage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). ↩

-

Audebert, “Spatial Strategies of Haitian Businesses in the Diaspora.” ↩

Sydney Rose Maubert (b. 1996) is a Haitian Cuban artist and architect based in Miami and Chicago. She holds degrees in architecture from Yale University and the University of Miami. She was a Cornell Strauch Fellow (2022–2024). Currently, she is the Rowe Fellow at IIT College of Architecture.