The Parrish Art Museum, designed by Herzog & de Meuron Architects, is an important contribution to a very necessary conversation about architecture—how to design in the face of abrupt changes in the global economy. After years of architecture’s complicity in designing and visualizing improbable capitalist dreams, the global economy fell into crisis in 2008, marking a change in the fortunes of those firms that relied on an untroubled relationship between architecture and political economy. The process of designing Parrish Art Museum by Herzog & de Meuron, by contrast, stands as a lesson to the discipline and to the practice of architecture. This lesson is not only that architecture has tools with which to overcome the global economic crisis, but also that it might instruct the future of that economy through design solutions that are at hand. The major challenge is how to assess this new condition of sobriety within architecture, a sobriety that is well demonstrated by Herzog & de Meuron in the design process for the Parrish Museum of Art. It is a building that asks us to consider how we might better educate new generations of architects to prepare for similar upheavals of extreme reality in the future.

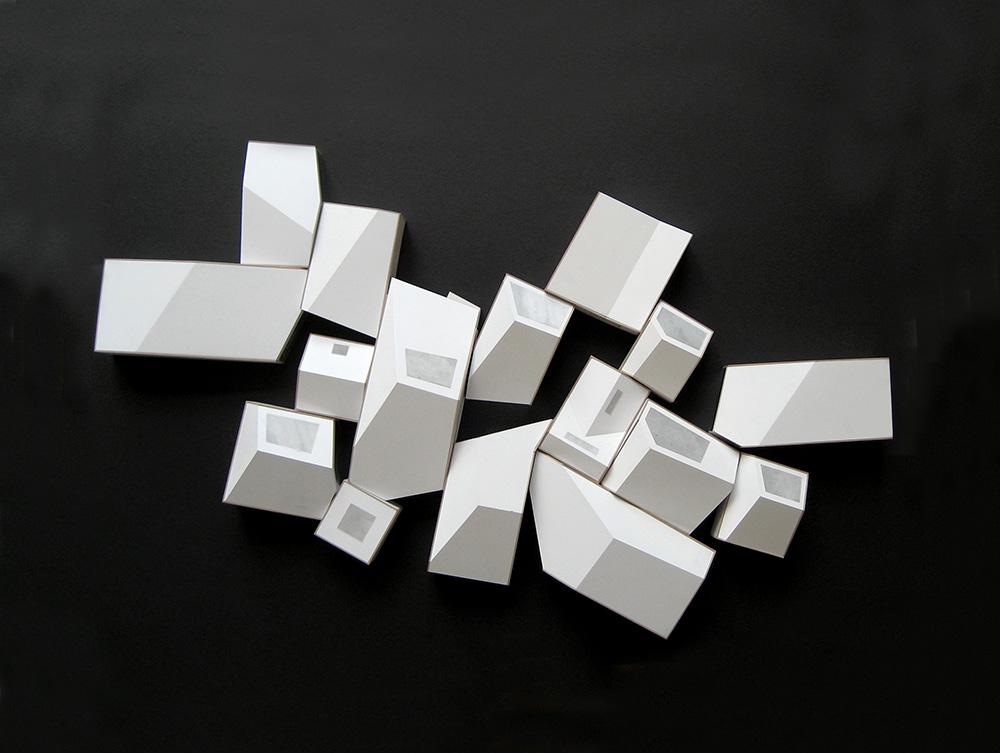

Completed in 2012 to house and display a private collection of modern art, The Parrish Art Museum building in Watermill, Long Island (a hamlet in the Hamptons) replaced the original museum—a Beaux-Arts kunsthalle in nearby Southampton—that had been outgrown by the institution and its collection.1 The architects were commissioned to design the project in 2005. Their original concept was a collection of different volumes assembled in a village-like setting, whose individual buildings resembled the barns-turned-artists’ studios common to the area. This dense and amalgamated art village was intended to operate as a dispersed museum, its multiple barns offering differentiated forms of display that visitors could experience according to their individual choices.2

Revealed to the public in September 2006 and globally circulated via online and print publications, the design would become well known but remained unbuilt.3 In 2008, following the burst of the global economic bubble, the Parrish Art Museum announced that it could not raise enough money for the design’s projected budget. The price of realizing its architecture was deemed too high an investment for the artwork—a strong but regionally focused and regionally scaled collection—that it would hold. Along with the numerous other building projects terminated or put on hold during this time, the cancellation of the original Parrish proposal showed that architecture was receiving its share of the economic blow. It seemed that everything extravagant in architecture that was imaginable until 2008 could not be produced anymore. Architecture’s practice would now involve following the new framework of reality or exploring the new realm of austerity.

This design persists, however, in the form of numerous models, images, and studies. Dispersed through media channels, these models and drawings have gained the status of a virtual masterpiece. In addition, this design was carried further by younger architects who copied and modified it for their own ends (including copycat versions submitted in a proposal for Ai Weiwei’s Ordos 100 project in Inner Mongolia, which is de facto co-curated by Herzog & de Meuron), as well as by their own office itself in their own subsequent projects. Through this work the art village concept, whether imagined as an art facility or a residence, has gained the curious status of a typology without precise content. A particular design project that was stopped has given rise to a virtual and elastic typology, one that is new in the respect that it can be reiterated differently, due to the loose symbolic value of its formal characteristics—a collection of barns used by artists as a means of refuge from the city and the rules of the metropolis.

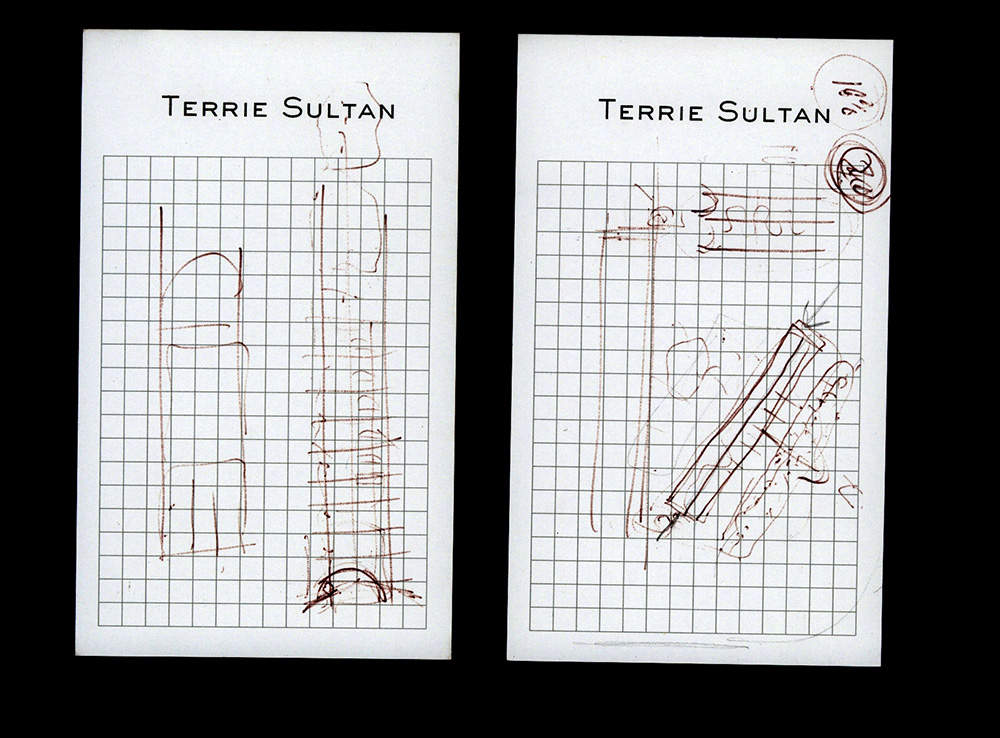

An abrupt change takes place for the Parrish project, both ideologically and pragmatically, in 2008. The museum invites the architects back to the table to propose a new scheme that would be many times less expensive than the original. During a meeting with the client, Ascan Mergenthaler, the partner in charge of the project at Herzog & de Meuron, makes a napkin sketch of a new concept for the museum that is far simpler and cheaper—a double-pitched roof structure, 600 feet long, inspired by a typical Long Island barn. A section of the barn is extruded, creating large overhangs on all sides and transforming the volume into a sophisticated version of the barn’s ideal: the cabin. This museum cabin is simple in plan. It has no corridors, only partitions that define its various areas. The double-pitched roof allows for full height spaces on both sides of the central spine. Due to its width, this spine is also used as a gallery, recalling the word’s etymological connection with the Italian galleria, a corridor of display linking a point A with a point B.

The Parrish Art Museum released an image of the new proposal to the media. This image depicts the flat and long cabin building sited within the very same landscape view that had been shown in the original art village proposal. Apparently the idea for the bushy, wild landscape had not changed; only the architecture had. The flat line of the art cabin, dominating the site, replaced the collection of multiple versions of small barns. This flat line could be read as a sign of architecture’s abrupt shift—from the pre-2008 bubble economy, which had allowed for multiplicity and archipelagos of distinct spaces, to the post-2008 condition, in which all spaces were consolidated into one barn, the cabin.

The colleagues I know from Herzog & de Meuron (alongside other observers) admire this abrupt change in ideology, referring to the new, built version of the Parrish Museum as “The Flatliner.” Like the flat line stretching across an electrocardiogram when the heart stops working, this architectural trope is in critical need of acknowledgement—for delineating the imminent end of something, and for crying out for a method of resuscitation that will bring its patient back to life.

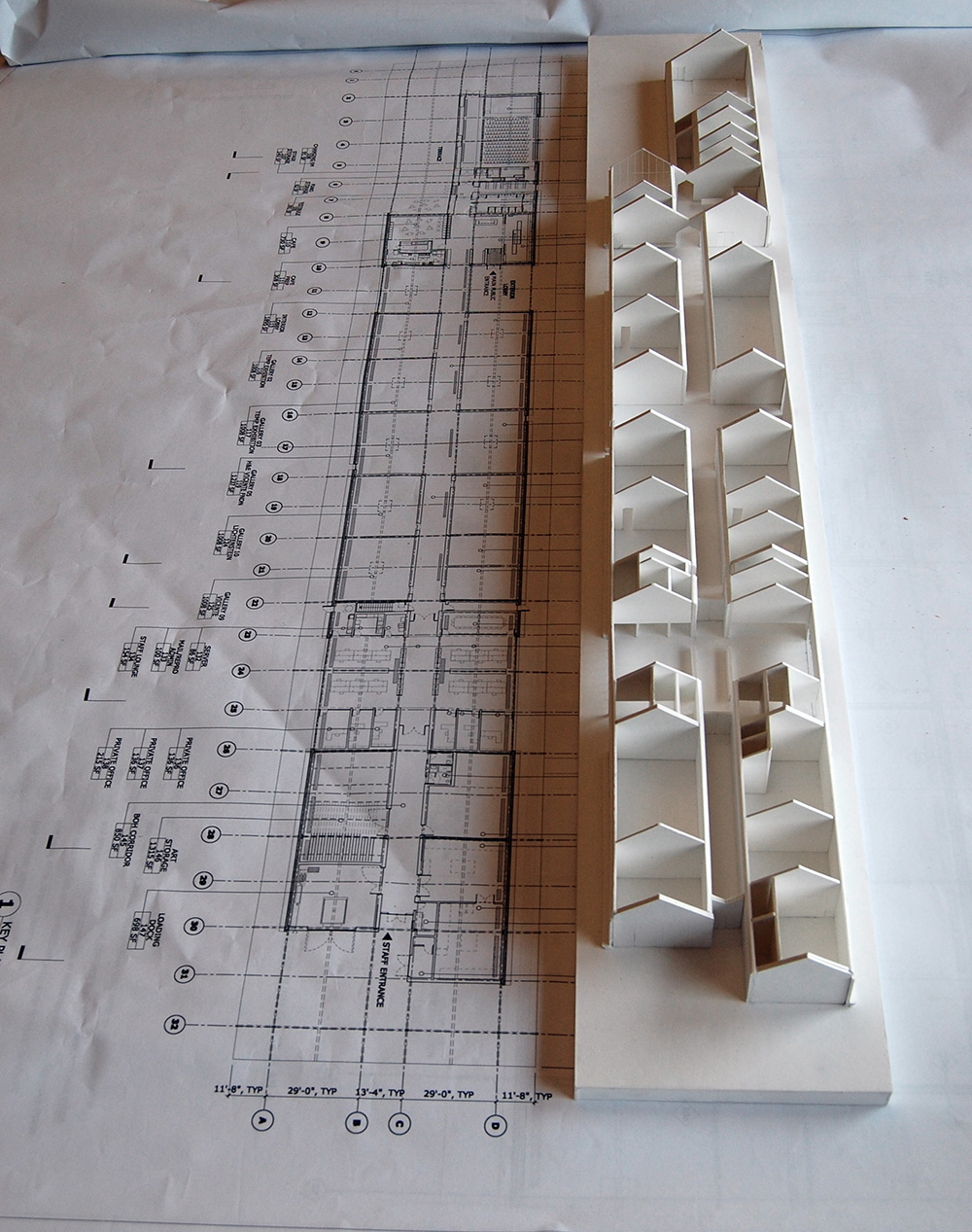

The estimated cost of the new design was a third of the original proposal’s. This was due in part to the architects’ decision to engage local builders very early on in the design process. With the new concept sketch in hand, they visited one local builder whose specialty was constructing high-end mansions on Long Island using sophisticated concrete. During a tour of some of his completed projects, the architects noticed a certain kind of rough concrete used in the basement of a clubhouse that the builder erected for the local golf club. This, responded the contractor, was the most economical and fastest-setting concrete his team could pour. This kind of concrete became the major exterior material of the Parrish Art Museum.

The shift that took place between the two Parrish Art Museum schemes seems to encapsulate a greater, office-wide shift in design practice and ideology at Herzog & de Meuron. (Other projects of theirs in the U.S. that express it well, though to a lesser degree, include the Pérez Art Museum and the 1111 Lincoln Road parking garage, both in Miami.) The changes evident in the firm’s work and working process since 2008 seem to align with a common corporate strategy during periods of financial trouble—preserve the company brand first and make all other operational decisions accordingly. With the Parrish project, they did not invert the well-known hallmarks of the office’s work; rather, they more deliberately fragmented, if not balkanized, their architectural approach and production. The positive aspects of such balkanization might be called diversification, in corporate parlance. In the case of their current practice, it involves developing a method of producing an architecture of well-crafted distinctions of architectural typologies. These typologies are in themselves so diverse that no urbanism can put them in a singular stylistic accord. Herzog & de Meuron choice to craft a cabin rather than a museum building for the Parrish is one move in this vein, and it can anchor a serious new discussion about emerging currents in the art of architecture.

That discussion should include an exploration of architects’ contemporary reliance on abrupt change—namely, how they are now attempting to make political-economic instability a generative factor in the design process, creating an artistic turn in architecture as its effect. This turn has been referred to (by Vladimir Pajkic, one of the firm’s partners) as the New Simplicity, which specifically refers to an intentional downsizing from the extravagant spatial propositions of the pre-2008 era. This shift to simple was extreme—and perhaps we can read in the Parrish Art Museum and other similar works a departure to extreme realism.

The focus on typologies that seems key to the New Simplicity approach appears to entail pushing the types’ elements to radical dimensions of materiality, such as the Parrish Art Museum’s 600-foot length. It also seems to involve stripping any ornament. A great deal has been published about the museum’s origins as a Long Island (potato) barn. Walking around and through the building, one notices the limited vocabulary of architectural detail. The mechanical systems are placed and hidden below the concrete pedestal, which is gently raised above the ground. This move allows the roof to be as light and thin as possible. Only three systems are integrated into it—roof structure with skylights, sprinklers, and fluorescent lights. Otherwise, the design strategies that upgrade the Parrish barn to a cabin involve baring its plain architectural elements involving engineering (with the exception of the decision to paint the exhibition walls white, thinly veiling the actual wall for the display of art).

Herzog and de Meuron’s second, realized Parrish Art Museum design should not be thought of as an alternative to their original art village concept. Instead the two designs have a parallel relationship, with the final design advancing their proposal for art museum-as-cabin. The major question that arises from examining the project in its wider context, as an architectural hinge between pre- and post-bubble, is this: How can Herzog & de Meuron’s choices inform the education of today’s young architects? How can we help prepare new designers to respond to abrupt changes affecting their own practices in the future?

Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss is an architect living and working in New York. He is on the faculty at Columbia University GSAPP, where he investigates architecture traversing beyond political power. In 2003 he founded Normal Architecture Office (NAO) and is co-founder of the School of Missing Studies (SMS). His books include Socialist Architecture: The Vanishing Act (2012), Evasions of Power: On the Architecture of Adjustment (2008), and Almost Architecture (2006). In 2006–07 he worked with Herzog & de Meuron as architect and researcher of urban cultures.